Abstract

Objective

To gain insight into the advance care planning (ACP) content provided on dementia associations’ websites in Europe.

Methods

We conducted a content analysis of dementia associations’ websites in Europe regarding ACP information, using deductive and inductive approaches and a reference framework derived from two ACP definitions.

Results

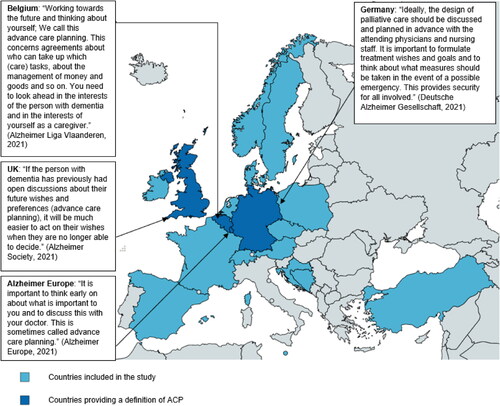

We included 26 dementia associations’ websites from 20 countries and one European association, covering 12 languages. Ten websites did not mention ACP. The information on the remaining 16 varied in terms of themes addressed and amount of information. Four explicitly define ACP. Several websites made multiple references to legal frameworks (n = 10, 705 excerpts), choosing legal representatives (n = 12, 274 excerpts), and care and treatment preferences (n = 14, 89 excerpts); while themes such as communication with family (n = 9, 67 excerpts) and professionals (n = 9, 49 excerpts) or identifying personal values (n = 9, 73 excerpts) were mentioned on fewer websites or addressed in fewer excerpts.

Conclusion

ACP content is non-existent in 10 out of 26 dementia associations’ websites. On those that have ACP content, legal and medical themes were prominent. It would be beneficial to include more comprehensive ACP information stressing the importance of communication with families and professionals, in line with current ACP conceptualisations framing ACP as an iterative communication process, rather than a documentation-focused exercise.

Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) has been defined as an ongoing process that enables individuals to explore and identify their values, reflect upon the meanings and consequences of serious illness scenarios and define goals and preferences for future care and medical treatment. It also involves people discussing these preferences with family and healthcare providers, appointing a proxy decision-maker and recording these preferences and choices (Rietjens et al., 2017; Sudore et al., Citation2017). Dementia is a progressive neurodegenerative illness that leads to significant cognitive and functional decline. ACP has been described as an essential part of social health for people with dementia as it promotes their capacity to exercise choice and autonomy and fulfil their societal potential (Dröes et al., Citation2017). ACP is of great importance for people with dementia and their families as it enables individuals to discuss wishes and goals for health and end-of-life care before they lose decisional capacity (Dixon et al., Citation2018). It has also been suggested that ACP can be informed by health behaviour theories (Fried et al., Citation2009; Sudore et al., Citation2013), highlighting the importance of knowledge in ACP engagement. However, lack of knowledge about what ACP involves was found to be a significant barrier to engaging in ACP among people with dementia and their families or those close to them (Tilburgs et al., Citation2018; van der Steen et al., Citation2014).

People with dementia and their families have expressed concerns about unmet information needs regarding the trajectory of dementia, advance care planning and available care options (Dening et al., Citation2017; Dickinson et al., Citation2013; Samsi & Manthorpe, Citation2013). Although healthcare professionals are generally regarded as the most useful source of information for healthcare advice (Allen et al., Citation2020), a growing number of individuals use the Internet when searching for information about health conditions and treatment options (Fischer et al., Citation2014). For people with dementia specifically, according to a recent scoping review, the Internet has become the most highly utilised source of information and the most preferred source of information for people with dementia and their families (Soong et al., Citation2020).

However, potential limitations of information provided on the Internet include the risk of it being incomplete and of uncertain quality. The most common type of websites accessed by people with dementia to look for dementia-specific information are those of dementia associations and charities, and government-run websites, as they are seen as trustworthy in terms of quality of information (Allen et al., Citation2020). Several studies have examined the general content of websites providing information for people with dementia and their family carers, investigating among others diagnosis and management of dementia, young-onset dementia, prevention or assessing the whole content of websites (Anderson et al., Citation2009; Dillon et al., Citation2013; Jones et al., Citation2018; Robillard & Feng, Citation2017). Studies and guidelines have also addressed the accessibility and usability of websites for people with dementia, to investigate whether all technological features are dementia-friendly (Ghorbel et al., Citation2017; Savitch & Zaphiris, Citation2005).

So far there have been no studies of which and how much ACP content is available on dementia associations’ websites. Exploring to what extent and ways in which ACP content is addressed (i.e. which subjects are addressed with regards to ACP and to what extent), as well as identifying the accessibility and readability of the content are important steps within efforts to improve knowledge about ACP for people living with dementia and their families. Therefore, this study aims to gain insight into the ACP content provided on their websites by dementia associations in Europe. We explore the following research questions: [1] what ACP content is available on dementia associations’ websites in Europe? and [2] is the ACP content on these websites provided in an readable and accessible way for people with dementia and their families?

Methods

We conducted a content analysis of information related to ACP on European dementia associations’ websites. We used the reporting guideline developed by Kable et al. (Citation2012) to structure our paper. As the study uses data freely available in the public domain, ethics approval was not required.

Eligibility

Eligible websites were the official websites of international and national dementia associations in Europe (i.e. northern, southern, eastern, and western Europe) who were affiliated members of Alzheimer Europe. Alzheimer Europe is a non-governmental organisation aimed at raising awareness of all forms of dementia by creating a common European platform through co-ordination and co-operation between Alzheimer organisations throughout Europe. All eligible websites were included. To account for potential differences in the organisation of health and social care competencies between countries, the dementia associations were asked to forward links to regional websites if they deemed that they would offer more information on ACP. This measure aimed to ensure that we did not miss any relevant ACP content during the screening process. We contacted the dementia associations through email and sent one follow-up email in case of non-response within a two-week period.

We included websites available in the following languages: English, French, German, Dutch, Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian, Spanish, Danish, Norwegian, Czech, Swedish, Polish and Turkish. These specific languages were selected based on the languages covered by the authors and members of the DISTINCT network. DISTINCT is a project funded under the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 Marie Sklodowska Curie programme, which the present study was part of. Only content aimed at a broad audience was included in the analysis. If reports and documents clearly stated that they were specifically aimed at health and social care professionals or legal experts, they were excluded.

Identification of the ACP content on the websites

We accessed the websites of dementia associations available in the languages mentionned above, and screened them for ACP content using as reference key terms pertaining to ACP as identified in the ACP definitions of Rietjens et al. (Citation2017) and Sudore et al. (Citation2017). Specifically, we searched for content using the following search terms: (1) advance care planning; (2) planning for the future; (3) communicating about the future; (4) personal values and preferences; (4) preferences for future care or treatment; (5) planning for the end of life; (6) proxy or substitute decision-makers; and (7) advance directives.

In addition, all dementia associations whose websites were included in the study were contacted and asked to forward the links to the ACP information published on their websites to ensure we did not miss any information, and to ensure we include information that is considered by the associations themselves to relate to ACP.

Data extraction

We screened all included websites for ACP content in December 2020 and January 2021. All pages on each website were manually searched for the key themes described above, using the find function (“CTRL-F”), and embedded search bars. All ACP related content, which included webpages and available PDF documents (e.g. information sheets, brochures, or reports) to which the website linked directly, was downloaded. .

We extracted the ACP content of all websites, and all non-English websites were translated for analysis using the online translation tools DeepL or Google Translate and then checked by native speakers, either one of the authors or a member of the DISTINCT network, before being approved for analysis. All documents were uploaded into the qualitative analysis software NVivo 12 and the included text files created based on the ACP content extracted from the websites (i.e. webpages and PDFs) were analysed for content by two independent reviewers (FM and CD).

Content analysis of ACP content and coding technique

This study involved a qualitative content analysis of the ACP content, following the method described by Bengtsson (Citation2016). We conducted a directed content analysis, which involved: (1) identifying important key concepts as initial coding, (2) sorting data in the predetermined categories, (3) highlighting unsorted data that is potentially relevant, and (4) group highlighted data into new categories (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). Content analysis was chosen for its strengths in systematically categorising large volumes of text-based data, and the ability to assist in interpreting patterns occurring in the text.

We first created a reference framework that outlines criteria for determining that content concerns ACP. The development of such a reference framework has been used previously to identify palliative care content in policy documents concerning healthcare for older people (Pivodic et al., Citation2021). The reference framework was based on two recognized ACP definitions (Rietjens et al., Citation2017; Sudore et al., Citation2017), which we broke down into important themes. We created three overarching categories, within which key ACP themes could be classified. The overarching categories were: defining ACP, the legal and medical aspects of ACP, and the quality of life, personal, social and practical aspects of ACP. The final ACP themes included within these categories were: definition of ACP; legal frameworks; legal representatives; care and medical treatment preferences, including end-of-life care; documentation of decisions; personal values and life goals; communication and discussions with family; communication and discussions with health professionals; documentation sharing; timing; meanings and consequences of potential serious illness scenarios; and uncertainties of serious illness scenarios (see ). Appendix 1 gives a more detailed explanation of each theme within our reference framework.

Table 1. Overview of the deductive categories and themes.

Two researchers (FM & CD) each coded the ACP content from each website independently using the reference framework. Where text was determined to represent a theme that was not included in the reference framework, a new theme was created using an inductive approach. The inductive approach of the ACP content was used to allow certain themes to emerge from the data, independently from the reference framework based on the definition of ACP. Inter-coder reliability was then established by discussing disagreements and re-coding content until an agreement was reached. The qualitative analysis software NVivo 12 was used to assign and organise codes, as well as visualising the data through hierarchy charts.

Descriptive analysis of website accessibility and readability

To make an inventory of the different accessibility and readability features of the websites, a descriptive analysis was performed, based on the DEEP guide on creating websites for people with dementia (DEEP: The Dementia Engagement & Empowerment Project, Citation2013a) and the DEEP guide on writing dementia-friendly information (DEEP: The Dementia Engagement & Empowerment Project, Citation2013b). First, we assessed the websites based on accessibility, that is, how well the website was able to meet the needs of people with dementia, and whether it included the following items: clear headings, clear home link, clear site map, print option, text to speech option, text size option, contrast option, and clear hyperlinks. In addition, we also assessed the ACP webpages on readability, that is whether the content is presented in a way that is as easy to understand as possible. We only assessed the readability of the ACP content included in the analysis, and not of the associations’ websites as a whole. We included the following items: use of simple language, use of pictures, use of videos, use of abbreviations and whether they are defined or not, and use of jargon and whether it is defined or not. Language was evaluated as simple if more than half of the content met the following criteria: (1) short sentences (20 or fewer words), (2) paragraphs constructed with five or fewer sentences, (3) over half of the passages written in active voice, (4) lists used to break up blocks of texts, and (5) jargon was used and explained. These evaluation criteria were based on a previous study conducting descriptive analyses of telehealth websites (Whitten et al., Citation2011).

Results

Characteristics of the websites included

We included websites from 26 associations, originating from 20 different countries in Europe and one European association. Eight dementia associations answered our request to forward the ACP content of their website, which allowed us to check that we did not miss any content in our extraction process, that the associations themselves considered to address ACP. From the 26 associations identified, all are non-profit organisations and politically and religiously independent. Their mission statements and objectives range from supporting and informing people with dementia and their carers or raising awareness about dementia, to advocating for patients’ rights and encouraging research, or even ensuring collaboration between associations. In total, 20 associations mention providing support or information to people with dementia and their families as one of their primary objectives. Of the six remaining associations, five of them (i.e. the National Alzheimer League Belgium, the Malta Dementia Society, the Norwegian Health Association, the Spanish Alzheimer Confederation, and the Turkish Alzheimer Association) focus solely on advocacy and organisational coordination and Alzheimer Europe is an umbrella organisation of national Alzheimer associations whose focus is on advocacy and research at European level. An overview of mission statements can be found in Appendix 2.

ACP content provided on the websites

Out of the 26 associations’ websites included, 10 did not mention anything about ACP. The remaining websites varied widely in the amount of content provided, with some containing a single webpage on ACP (e.g. Alzheimer Austria or Alzheimer’s association of Turkey) while others provide a much larger range of content on several webpages (e.g. Alzheimer Europe or Alzheimer Society in the UK) (see Appendix 3).

Across the 16 websites that mentioned ACP, all 12 ACP themes identified in our reference framework were addressed to some extent. We present these themes in three overarching categories: defining ACP, the legal and medical aspects of ACP, and the quality of life, personal, social, and practical aspects of ACP . The analysis also identified four themes that emerged from the data and that were recurring across several websites: (1) reviewing ACP, (2) difficulties of ACP conversations, (3) potential consequences of not doing ACP, and (4) decision-making capacity.

Table 2. ACP themes identified per dementia associations’ website1.

Defining ACP

Four websites formulated a definition of ACP (). Two of these definitions (German and Belgian - Flemish websites) focused on making decisions for future care and medical treatments and the choice of a legal representative, whereas the other two (UK and Alzheimer Europe websites) remained more general and referred to ‘preferences’ or ‘wishes’ for the future. Two of four websites with definitions (from Alzheimer Europe and Germany) put forward the importance of discussing ACP with a health care professional. All four emphasized the importance of the ACP process and its potential benefits ().

Figure 1. Definition of ACP per country.

*All definitions are forward-only translations from the original websites.

**Definitions from: ( Alzheimer’s Society, Citation2021b; Alzheimer Europe, Citation2021; Alzheimer Liga Vlaanderen, Citation2021; Deutsche Alzheimer Gesellschaft, Citation2021 ).

Table 3. ACP themes identified on the dementia associations’ websites.

Table 4. Website features identified per dementia associations’ website.

Legal and medical aspects of ACP

The theme legal frameworks was assigned to excerpts which included explanations of national laws that govern the ACP process and accounts for more than 60 percent of the total of excerpts, with 705 excerpts across 10 websites. These included laws on advance directives, power of attorney, euthanasia, or protection of vulnerable populations. A further theme is the choice of a legal representative (n = 12 websites, 274 excerpts). The theme has been defined to represent the exploration and appointment of a legal representative. Documentation of decisions and Care and medical treatment preferences was also addressed on dementia associations’ websites (n = 11, 88 excerpts and n = 14, 89 excerpts respectively). Care and medical treatment preferences included decisions such as ‘limiting or stopping treatment and end-of-life care’ or ‘going into residential care or a nursing home’, which were situations often mentioned on the websites, while documentation of decisions focused on writing these decisions in living wills or advance directives. These documents are described as ways to plan medical care and legal affairs, as well as financial affairs ().

Quality of life, personal, social and practical aspects of ACP

The identification of personal values and life goals was mentioned on nine websites, although in considerably fewer cases (73 excerpts) than the medical and legal themes. Websites addressed the exploration of wishes based on personal values and life goals, and important quality of life domains for the person. These included for example, ‘daily habits and wishes about food, hygiene, dress, physical activities and cultural activities’ or ‘their likes and dislikes, their background (including ethnicity or religion), what they like to be called, the important people or places in the person’s life, what helps them relax, how they take their medication, their normal routines, if they wear glasses or a hearing aid, what they like to do for themselves and what they need help with’ ().

Communication with health professionals and Communication with family and Sharing of documents were found in the same number of websites (n = 9); they were addressed in 67, 49 and 36 excerpts respectively. In several instances, websites encouraged people with dementia to discuss the future with family or trusted individuals (n = 9, 67 excerpts), as well as with health professionals (n = 9, 49 excerpts). In cases where advance directives were mentioned, some websites (n = 9, 36 excerpts) also encouraged people with dementia to share these advance decisions documents, giving the argument that the more people are aware of decisions and wishes, the more they can be respected ().

Besides references to future wishes and communication, 12 websites mention the timing of ACP, advocating for ACP to be done as early as possible (in 58 excerpts). Some websites also address meanings and potential consequences of future serious illness scenarios by discussing available treatment options (and their possible benefits or lack thereof for the patient) (n = 10, 58 excerpts). Similarly, some highlight and explore the uncertainties associated with a dementia diagnosis and explain their consequences for ACP (n = 9, 34 excerpts) ().

Emerging themes

Regarding the topic of Reviewing ACP (n = 7, 13 excerpts), some websites emphasize the fact that ACP decisions are not fixed and can be changed. These websites then suggest regularly checking whether decisions still fit with the preferences of people with dementia, for as long as this is possible. The topic of decision-making capacity was also recurrent in the ACP content on some dementia associations’ websites (n = 9, 27 excerpts). These websites highlight the decline in capacity associated with dementia and use it as an argument to promote ACP ().

Moreover, references to what would happen if people did not do ACP were a recurring theme on different websites. The theme consequences of not doing ACP included potential future scenarios where the family does not know the preferences of the person with dementia and must choose on their behalf which treatment they should or should not receive (n = 5, 18 excerpts). Finally, several websites pointed to the difficulties of ACP conversations (n = 6, 15 excerpts) and the emotional impact that they can have on the person with dementia and the family.

Descriptive analysis of website features: Accessibility and readability of the ACP content

For accessibility and readability, we only assessed the features of the webpages where ACP content was available (16 out of 26 total websites) (). Overall, all these websites used a consistent style and font size within each one (n = 16). Almost all had an explicit ‘home’ link (n = 11), and seven had a site map (i.e. visible hierarchical listing of webpages). The majority always had clear headings visible (n = 14) and only one did not indicate hyperlinks clearly. Seven websites had a print option. Few of the websites allowed for the adjustment of font size (n = 6), adjustment of contrast (n = 2) or had a text to speech option (n = 2).

Five readability characteristics were examined on the websites that addressed ACP (16 out of 26 total websites). Six made use of pictures and two of videos. Ten websites had at least half of their ACP content presented in simple language on the webpages addressing ACP specifically. In addition, all these websites avoided the use of abbreviations and acronyms or defined them the first time they were used on the pages (n = 16). Jargon (e.g. advance directives, proxy decision maker, power of attorney) was used on most websites to explain advance care planning; jargon was also defined and explained on all websites (n = 16).

Discussion

Our study focused on the extent to and ways in which, dementia associations in Europe address ACP on their websites, as well as the accessibility and readability of this content for people with dementia and their families or those close to them. We found that more than a third of the websites included in the study (10 out of 26) did not address ACP at all. We identified 16 websites providing some content on ACP that people with dementia and their families might turn to. Three websites (i.e. Alzheimer Europe, Alzheimer Society—UK, and the German Alzheimer Society) addressed all ACP themes of our reference framework. The extent to which each ACP theme was addressed on the remaining websites varied greatly. All websites fulfilled some accessibility and readability criteria for people with dementia, although not all characteristics identified by the DEEP guides were accounted for.

Legal and medical themes largely dominated the content on the websites, representing more than two thirds of all excerpts. Most websites that addressed ACP focused primarily on the completion of advance directives, which revolved around three domains: medical care, legal affairs, and financial affairs. Other key ACP themes, such as communication with family, communication with health professionals, sharing of decisions and the identification of personal values and life goals seem largely to be under-addressed. This is an important gap, given that the drafting of advance directives should be preceded by a process of communication between the person with dementia, their family and their healthcare providers. This imbalance may reflect that ACP still has a strong medical and legal focus. Traditionally, ACP has focused heavily on the process of preparing in writing through (i) completing advance care documents, where people can record which treatment they would or would not like to receive at the end of life (such as feeding tube or withholding/withdrawing life support treatments) in the event that they would not be able to take decisions themselves, and (ii) choosing a legal representative, i.e. a formal arrangement whereby a person nominates another person to act in his/her name and make decisions on their behalf (Bosisio et al., Citation2018; Dickinson et al., Citation2013; Robinson et al., Citation2012). However, the concept of ACP has considerably evolved over the past decades, going from this documentation-focused process to a broader concept of an iterative communication process between the person with dementia, their family members and health professionals about future care, which is not limited to discussing medical treatment preferences (Prince-Paul & DiFranco, Citation2017; Sinclair et al., Citation2016; Van den Block, Citation2019). This is also reflected in the current European definition of ACP, which states: “advance care planning enables individuals to define goals and preferences for future medical treatment and care, to discuss these goals and preferences with family and health-care providers, and to record and review these preferences if appropriate.”(Rietjens et al., 2017). A recent umbrella review on ACP for people with dementia also showed that person-centred ACP conversations and communication tailored to the wishes of the person with dementia are of utmost importance in the process of ACP for people with dementia and their families (Wendrich-van Dael et al., Citation2020). However, few of the dementia associations’ websites highlight the importance of communication in ACP.

We also identified four themes that had not been included in our initial reference framework. Our reference framework was based on existing definitions of ACP (Rietjens et al., Citation2017; Sudore et al., Citation2017), which were not specifically developed for people with dementia. The themes that emerged from the data appeared to be especially important in the context of dementia, i.e. the gradual loss of decisional capacity, the need to regularly review wishes and the implications of not having done ACP prior to loss of capacity, all of which have been described in the literature on ACP for people with dementia (Sellars et al., Citation2019; Song et al., Citation2019; Wendrich-van Dael et al., Citation2020). Moreover, we also found that six websites addressed the difficulty of having ACP conversations. This is in line with research that has found that people with dementia and their families often face emotionally difficult conversations and experience tensions within the family when discussing ACP (Sellars et al., Citation2019; Wendrich-van Dael et al., Citation2020). Different patient populations can have different ACP needs and face different challenges. While the reference framework based on the ACP definitions addresses the process and subject areas of ACP, these emerging themes illustrate the importance of tailoring content provided on ACP on websites to the needs of different populations by, for example, addressing the specific difficulties faced by people with dementia and their families. This finding may highlight potential gaps in current ACP conceptualisations.

Finally, we analysed the accessibility and readability of the ACP content on dementia associations’ websites. Most websites met some of the accessibility and readability criteria set forth by the DEEP guides (DEEP: The Dementia Engagement & Empowerment Project, Citation2013a, Citation2013b). Most websites had clear formatting, home link, and headings as well as showed a clear sitemap. However, features such as print option, text-to-speech option or font and contrast adjustments were less often offered. Furthermore, although most offered content in a simple language, the use of pictures and videos to support content was less widespread. It can be argued that the target audience of dementia associations’ websites are not necessarily people with dementia or their families, but rather policy makers, legal experts or the general public, hence content may not need to meet these accessibility and readability criteria. Looking at mission statements of each respective association shows the variety of objectives and audiences that are targeted. Objectives ranged from supporting people with dementia and their families, to informing the general public (including people with dementia), or advocating for better representation and patient rights. A few associations (such as Alzheimer Europe for example) solely focus on advocacy and research, which may explain the differences in accessibility and readability of the ACP content. However, there is no consistent pattern between the different mission statements of the associations and the accessibility and readability of their ACP content. As most national associations mentioned supporting people with dementia and their families as one of their goals, we argue that they should generally strive for all content to meet these accessibility and readability criteria.

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the content provided online on the topic of ACP in relation to dementia. This study has a strong international focus and provides a good representation across Europe with countries included from northern, eastern, central, southern, and western Europe. There are some study limitations that need to be considered. First, we cannot exclude that we have missed some relevant content provided on the websites of the dementia associations in the different countries included in the study. Although we used a rigorous method to screen the websites, we relied on the cooperation of dementia associations to flag any missing ACP content or regional associations’ websites with additional content. Only eight dementia associations answered our query to check the ACP content we had extracted. Furthermore, given the global access to the Internet, we cannot exclude that a European audience could find information on ACP on websites based in other parts of the world, which were not included in this study. We hope that this research will prompt other studies of this type in other world regions. Second, translations of the ACP content on the websites were forward-only translations, meaning that the equivalences of the English translation with the original versions were not verified, and relied solely on the work of one translator per language. Third, although the method selected allowed for a thorough screening of the ACP content on dementia associations’ websites, it does not provide any indication of the use of these websites and ACP content by people with dementia and family carers, nor of how they appraise this content.

Overall, our results highlight opportunities for dementia associations in Europe to provide comprehensive ACP information on their websites. Lack of or insufficient knowledge about ACP has been identified as one of the factors hindering ACP in people with dementia (Dickinson et al., Citation2013). Dementia associations’ websites are an ideal place to provide this information to a wide public. We thus recommend that dementia associations adopt a more comprehensive approach to providing ACP content on their website, using the broad ACP framework developed in this paper to screen their content. ACP content should aim to address all categories of the framework, but also take into account disease-specific needs in terms of ACP. Therefore, although this framework can serve as initial guidance for the provision of ACP content, further research is needed to identify how ACP can be made accessible for people with dementia and how they can be best informed about ACP. There is also a need for better ACP tools for people with dementia that dementia associations could refer to. Research should focus on how to promote a broader view of ACP that not only addresses legal and medical information, but combines it with more practical guidance on how to engage in and communicate about ACP. Further research could focus on comparing the ACP content of dementia associations’ websites with the content of websites concerned with other conditions such as cancer.

In the future, it would also be important to assess whether the content provided on these websites is deemed to be useful and accessible by people with dementia and their families. We would suggest that dementia associations, researchers, or other entities wanting to provide information about ACP use the DEEP guides on creating websites for people with dementia and on writing dementia-friendly information (DEEP: The Dementia Engagement & Empowerment Project, Citation2013a, Citation2013b) or similar guidelines, and involve people with dementia and their families in content creation to ensure that their voices are heard and that cultural nuances are taken into account.

Conclusion

This study showed that ACP content and its accessibility and readability for people with dementia varied across dementia associations’ websites in Europe. Although most websites provide some information on ACP, several key ACP themes have been addressed infrequently, or are not addressed at all. We can therefore conclude that there are several opportunities for improvement of ACP content provision on dementia association websites in Europe. It would be beneficial to include more comprehensive ACP information by stressing the importance of communication processes, in line with recent conceptualisations of ACP.

This work was supported by Marie Sklodowska-Curie; Fondation Francqui - Stichting; Research Foundation Flanders.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (43.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the dementia associations for their help in identifying ACP content on their websites and Jane Ruthven for English editing. We also thank Beliz Budak, Gianna Kohl, Jaroslav Cibulka, Simone Felding, Mauricio Molinari Ulate & Viktoria Hoel for their help with the translation of the ACP content on the websites.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen, F., Cain, R., & Meyer, C. (2020). Seeking relational information sources in the digital age: A study into information source preferences amongst family and friends of those with dementia. Dementia (London, England), 19(3), 766–785. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301218786568

- Alzheimer Austria. (2021). Rechtliches & finanzielle Fragen. Retrieved December 14, 2020, from https://www.alzheimer-selbsthilfe.at/leben-mit-demenz/rechtliches-finanzielle-fragen/

- Alzheimer Europe. (2021). The initial period of adaptation (shortly after diagnosis). Retrieved January 20, 2021, from https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/Ethics/Ethical-issues-in-practice/2014-Ethical-dilemmas-faced-by-carers-and-people-with-dementia/The-initial-period-of-adaptation-shortly-after-diagnosis/(language)/eng-GB

- Alzheimer Liga Vlaanderen. (2021). Werken aan de toekomst, denken aan jezelf. Retrieved December 14, 2020, from https://www.alzheimerliga.be/nl/over-dementie/dementie/beginnende-dementie/werken-aan-de-toekomst-denken-aan-jezelf

- Alzheimer Nederland. (2021). Regeltips voor iemand met dementie. Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www.dementie.nl/omgaan-met-dementie/regelzaken/zorgbeslissingen-nemen/regeltips-voor-iemand-met-dementie

- Alzheimer Scotland. (2020). Dementia and the law in Scotland. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://www.alzscot.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/DementiaandlawinScotland_January2020.pdf

- Alzheimer Scotland. (2021). End of life care. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://www.alzscot.org/living-with-dementia/end-of-life-care

- Alzheimer Suisse. (2020). Rédiger des directives anticipées (en rapport avec une démence). Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.alzheimer-schweiz.ch/fileadmin/dam/Alzheimer_Schweiz/Dokumente/Publikationen-Produkte/163-33F_2020_Directives-anticipees.pdf

- Alzheimer’s Society. (2021a). Advance statements and dementia. Retrieved January 15, 2021, from https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-support/legal-financial/advance-statements-dementia#content-start

- Alzheimer’s Society. (2021b). Making decisions about end of life care. Retrieved January 15, 2021, from https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-support/help-dementia-care/end-life-care-making-decisions#content-start

- Alzheimerforeningen. (2020a). Plejebolig og plejetestamente. Retrieved December 15, 2020, from https://www.alzheimer.dk/er-du-paaroerende/vigtige-overvejelser/plejebolig-og-plejetestamente/

- Alzheimerforeningen. (2020b). Tal om døden. Retrieved December 15, 2020, from https://www.alzheimer.dk/er-du-paaroerende/den-sidste-fase/tal-om-doeden/

- Anderson, K. A., Nikzad-Terhune, K. A., & Gaugler, J. E. (2009). A systematic evaluation of online resources for dementia caregivers. Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet, 13(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/15398280802674560

- Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001

- Bosisio, F., Jox Ralf, J., Jones, L., & Rubli Truchard, E. (2018). Planning ahead with dementia: What role can advance care planning play? A review of opportunities and challenges. Swiss Medical Weekly, 148(51–52), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2018.14706

- Czech Alzheimer Society. (2015). Jak pečovat o nemocného v pokročilém stadiu demence. Retrieved December 15, 2020, from https://www.alzheimer.cz/pro-rodinne-pecujici/tipy-pro-pecujici/jak-pecovat-o-nemocneho-v-pokrocilem-stadiu-demence/

- de Alzheimer, C. E. (2019). Estudio jurídico del marco normativo integral para la garantía de derechos de las personas afectadas por Alzheimer y otras demencias. Retrieved December 18, 2020, from https://www.ceafa.es/es/que-comunicamos/publicaciones/estudio-juridico-frl-marco-normativo-integral-para-la-garantia-de-derechos-de-las-personas-afectadas-por-alzheimer-y-otras-demencias

- DEEP: The Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project. (2013a). Creating websites for people with dementia. https://www.dementiavoices.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/DEEP-Guide-Creating-websites.pdf

- DEEP: The Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project. (2013b). Writing dementia-friendly information. http://dementiavoices.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/DEEP-Guide-Writing-dementia-friendly-information.pdf

- Dening, K. H., King, M., Jones, L., & Sampson, E. L. (2017). Healthcare decision-making: Past present and future, in light of a diagnosis of dementia. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 23(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2017.23.1.4

- Dickinson, C., Bamford, C., Exley, C., Emmett, C., Hughes, J., & Robinson, L. (2013). Planning for tomorrow whilst living for today: The views of people with dementia and their families on advance care planning. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(12), 2011–2021.

- Dillon, W. A., Prorok, J. C., & Seitz, D. P. (2013). Content and quality of information provided on Canadian dementia websites. Canadian Geriatrics Journal: CGJ, 16(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.16.40

- Dixon, J., Karagiannidou, M., & Knapp, M. (2018). The effectiveness of advance care planning in improving end-of-life outcomes for people with dementia and their carers: A systematic review and critical discussion. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 55(1), 132–150.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.04.009

- Dröes, R. M., Chattat, R., Diaz, A., Gove, D., Graff, M., Murphy, K., Verbeek, H., Vernooij-Dassen, M., Clare, L., Johannessen, A., Roes, M., Verhey, F., & Charras, K., INTERDEM sOcial Health Taskforce. (2017). Social health and dementia: A European consensus on the operationalization of the concept and directions for research and practice. Aging & Mental Health, 21(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1254596

- Fischer, S. H., David, D., Crotty, B. H., Dierks, M., & Safran, C. (2014). Acceptance and use of health information technology by community-dwelling elders. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 83(9), 624–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.06.005

- Fried, T. R., Bullock, K., Iannone, L., & O’Leary, J. R. (2009). Understanding advance care planning as a process of health behavior change. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57(9), 1547–1555. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02396.x

- Gesellschaft, D. A. (2019). Vorsorgevollmacht, Betreuungsverfügung, Patientenverfügung. Retrieved December 15, 2020, from https://www.deutsche-alzheimer.de/fileadmin/Alz/pdf/factsheets/infoblatt10_vorsorgeverfuegungen_dalzg.pdf

- Gesellschaft, D. A. (2021). Palliative Versorgung von Menschen mit fortgeschrittener Demenz. Retrieved December 15, 2020, from https://www.deutsche-alzheimer.de/fileadmin/Alz/pdf/factsheets/infoblatt24_palliative_versorgung_dalzg.pdf

- Ghorbel, F., Métais, E., Ellouze, N., Hamdi, F., Gargouri, F., Miracl, L., & Sfax, U. D. (2017). Towards accessibility guidelines of interaction and user interface design for Alzheimer’s disease patients. ACHI, 143–149. Nice, France.

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Jones, B., Gage, H., Bakker, C., Barrios, H., Boucault, S., Mayer, J., Metcalfe, A., Millenaar, J., Parker, W., & Orrung Wallin, A., RHAPSODY Study Group. (2018). Availability of information on young onset dementia for patients and carers in six European countries. Patient Education and Counseling, 101(1), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.07.013

- Kable, A. K., Pich, J., & Maslin-Prothero, S. E. (2012). A structured approach to documenting a search strategy for publication: A 12 step guideline for authors. Nurse Education Today, 32(8), 878–886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.02.022

- Norwegian Health Association. (2021). Åpenhet og kunnskap. Retrieved December 18, 2020, from https://nasjonalforeningen.no/demens/etter-diagnosen/apenhet-og-kunnskap/

- Pivodic, L., Smets, T., Gott, M., Sleeman, K. E., Arrue, B., Cardenas Turanzas, M., Pechova, K., Kodba Čeh, H., Lo, T. J., Nakanishi, M., Rhee, Y., Ten Koppel, M., Wilson, D. M., & Van den Block, L. (2021). Inclusion of palliative care in health care policy for older people: A directed documentary analysis in 13 of the most rapidly ageing countries worldwide. Palliative Medicine, 35(2), 369–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320972036

- Prince-Paul, M., & DiFranco, E. (2017). Upstreaming and normalizing advance care planning conversations-A public health approach. Behavioral Sciences, 7(4), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7020018

- Rietjens, J. A. C., Sudore, R. L., Connolly, M., van Delden, J. J., Drickamer, M. A., Droger, M., van der Heide, A., Heyland, D. K., Houttekier, D., Janssen, D. J. A., Orsi, L., Payne, S., Seymour, J., Jox, R. J., & Korfage, I. J., European Association for Palliative Care. (2017). Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: An international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. The Lancet. Oncology, 18(9), e543–e551. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30582-X

- Robillard, J. M., & Feng, T. L. (2017). Health advice in a digital world: Quality and content of online information about the prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD, 55(1), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-160650

- Robinson, L., Dickinson, C., Rousseau, N., Beyer, F., Clark, A., Hughes, J., Howel, D., & Exley, C. (2012). A systematic review of the effectiveness of advance care planning interventions for people with cognitive impairment and dementia. Age and Ageing, 41(2), 263–269. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afr148

- Samsi, K., & Manthorpe, J. (2013). Everyday decision-making in dementia: Findings from a longitudinal interview study of people with dementia and family carers. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(6), 949–961. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610213000306

- Savitch, N., & Zaphiris, P. (2005). An investigation into the accessibility of web-based information for people with dementia [Paper presentation]. 11th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, (July).

- Sellars, M., Chung, O., Nolte, L., Tong, A., Pond, D., Fetherstonhaugh, D., McInerney, F., Sinclair, C., & Detering, K. M. (2019). Perspectives of people with dementia and carers on advance care planning and end-of-life care: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Palliative Medicine, 33(3), 274–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216318809571

- Sinclair, J. B., Oyebode, J. R., & Owens, R. G. (2016). Consensus views on advance care planning for dementia: A Delphi study. Health & Social Care in the Community, 24(2), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12191

- Song, M.-K., Ward, S. E., Hepburn, K., Paul, S., Kim, H., Shah, R. C., Morhardt, D. J., Medders, L., Lah, J. J., & Clevenger, C. C. (2019). Can persons with dementia meaningfully participate in advance care planning discussions? a mixed-methods study of SPIRIT. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 22(11), 1410–1416. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0088

- Soong, A., Au, S. T., Kyaw, B. M., Theng, Y. L., & Tudor Car, L. (2020). Information needs and information seeking behaviour of people with dementia and their non-professional caregivers: A scoping review. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-1454-y

- Sudore, R. L., Lum, H. D., You, J. J., Hanson, L. C., Meier, D. E., Pantilat, S. Z., Matlock, D. D., Rietjens, J. A. C., Korfage, I. J., Ritchie, C. S., Kutner, J. S., Teno, J. M., Thomas, J., McMahan, R. D., & Heyland, D. K. (2017). Defining advance care planning for adults: A consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 53(5), 821–832.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2016.12.331

- Sudore, R. L., Stewart, A. L., Knight, S. J., McMahan, R. D., Feuz, M., Miao, Y., & Barnes, D. E. (2013). Development and validation of a questionnaire to detect behavior change in multiple advance care planning behaviors. PloS One, 8(9), e72465. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072465

- The Alzheimer Socitey of Ireland. (2018). How do I plan for the future? Retrieved December 16, 2020, from https://alzheimer.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/18055-ASI-PlanForFuture-2018-web_low-res.pdf

- The Alzheimer Socitey of Ireland. (2021). Planning for the future. Retrieved December 16, 2020, from https://alzheimer.ie/living-with-dementia/i-am-a-carer-family-member/planning-for-the-future/

- Tilburgs, B., Vernooij-Dassen, M., Koopmans, R., van Gennip, H., Engels, Y., & Perry, M. (2018). Barriers and facilitators for GPs in dementia advance care planning: A systematic integrative review. PLoS One, 13(6), e0198535. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198535.t005

- Van den Block, L. (2019). Advancing research on advance care planning in dementia. Palliative Medicine, 33(3), 259–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216319826411

- van der Steen, J. T., van Soest-Poortvliet, M. C., Hallie-Heierman, M., Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D., Deliens, L., de Boer, M. E., Van den Block, L., van Uden, N., Hertogh, C. M. P. M., & de Vet, H. C. W. (2014). Factors associated with initiation of advance care planning in dementia: A systematic review. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD, 40(3), 743–757. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-131967

- Wendrich-van Dael, A., Bunn, F., Lynch, J., Pivodic, L., Van den Block, L., & Goodman, C. (2020). Advance care planning for people living with dementia: An umbrella review of effectiveness and experiences. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 107, 103576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103576

- Whitten, P., Holtz, B., Cornacchione, J., & Wirth, C. (2011). An evaluation of telehealth websites for design, literacy, information and content. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 17(1), 31–35. https://doi.org/10.1258/jtt.2010.091208