Abstract

Objectives: Secure adult attachment may promote health and well-being in old age, yet is understudied in this life phase. Consequently, we aim to examine associations between adult attachment and mental and physical health and quality of life, both concurrently and longitudinally.

Methods: We used three phases of the Whitehall II study (n = 5,222 to 6,713). Adult attachment was measured with the Relationship Questionnaire (RQ) at 48–68 years. Mental and physical health was measured concurrently and 14 years later; quality of life was measured five years later. We used linear regressions to examine associations, controlling for age, gender and education.

Results: Almost half, 46% of participants, were classified as secure, 13% as preoccupied, 34% as dismissing and 7% as fearful. Adult attachment was associated with mental and physical health, concurrently and 14 years later, and with quality of life five years later. Preoccupied and fearful participants had poorest mental health and quality of life; dismissing participants held an intermediate position. Insecurely attached participants tended to report poorer physical health.

Conclusions: Adult attachment has enduring associations with mental and physical health, which suggests that the construct of adult attachment itself is stable in this phase of the life course.

Introduction

In the search for factors promoting health and well-being in old age, the potential role of adult attachment has largely been overlooked. A dominant explanatory model in developmental psychology, attachment theory examines how mental representations of the self and significant others, and the relations between these two, influence intra and interpersonal functioning (Pietromonaco & Barrett, Citation2000). Despite the implications of this theory for the whole life span, surprisingly little is known about attachment phenomena in old age (Homan, Citation2018; Martin, Citation2018). In order to explore the role of attachment for health and quality of life in this life stage, this paper presents findings examining the relationship between these outcomes and attachment over a 14-year period spanning late midlife and old age.

Attachment theory

Attachment theory grew out of attempts to understand emotional responses of children who had been separated from their parents (Fraley, Citation2019). It is theorized that infants are born with an attachment system: an evolved set of emotions and corresponding behaviours that keep infants safe by maintaining proximity to their caregivers. Many infants develop a smoothly functioning—secure—relationship to their caregiver, but this is not guaranteed. With caregivers who are not sufficiently sensitive and responsive, infants may not develop the confidence that an attachment figure will be available when needed, leading to insecure attachment. Attachment patterns are suggested to be underpinned by mental representations—internal working models—of the self and caregivers (Bowlby, Citation1973, p. 235). With transition into adulthood, working models are generalized from caregivers to others in a person’s social networks, including romantic relationships (Hazan & Shaver, Citation1987).

Adult attachment is usually conceptualized along two dimensions: avoidance and anxiety. Avoidance concerns a person’s inner representations of others and the anxiety dimension concerns a person’s inner representations of the self. Together they yield four prototypical categories: secure, preoccupied, dismissing-avoidant and fearful-avoidant (Bartholomew, Citation1990; Pietromonaco & Barrett, Citation2000). Adults with a secure attachment style have developed a representation of the self as acceptable and worthy and anticipate others to be readily available, responsive and reliable. Comfortable with closeness in their relationships, they are not particularly worried about others rejecting them. Adults who hold a negative view of the self and a positive view of others—the preoccupied type—desire a high level of closeness with others and fear abandonment by them. Adults who hold a positive view of the self and a negative view of others—the dismissing-avoidant type—are uncomfortable with closeness and are overly self-reliant. The last group—the fearful-avoidant prototype—has negative models of both the self and others and reports both a desire for and a fear of closeness.

These internal working models have implications for close relationships in adulthood, in which securely attached individuals have greater capacities for cooperativeness, authenticity, interpersonal sensitivity and conflict resolution, which will tend to encourage a feedback loop of more positive relationship experiences (Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2016, pp. 396, 505). However, the impact of secure attachment extends beyond inter-personal functioning. The attachment system plays an important role in emotion regulation: a sense of attachment security acts as an inner resource for managing distress and restoring emotional composure (Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2016, p. 396). Insecurely attached individuals are more vulnerable to destructive cognitive processes of self-criticism or defensive self-enhancement, while securely attached people are able to maintain a sense of self-worth while recognizing their shortcomings. These emotional and cognitive characteristics protect securely attached individuals from demoralization and mental illness. Further, they enable constructive strategies to be deployed in order to deal with problems and reach valued goals, in turn enhancing impressions of self-efficacy, achievement and growth.

Implications of attachment for health and quality of life in old age

Although attachment theory is a developmental model that is pertinent for the whole lifespan, most empirical research has focussed on early childhood and young adulthood (Diehl et al., Citation1998; Magai et al., Citation2016). Aside from the fact that the effects of adult attachment in later life are under-researched, use of an attachment-theoretical perspective in this life stage may be significant for several reasons. The attachment system may gain particular relevance in later life, given the increased likelihood in old age of declines in physical, cognitive and social function—with implications for vulnerability and autonomy—and of losses and illnesses of attachment figures (Bradley & Cafferty, Citation2001; Cicirelli, Citation2010; Van Assche et al., Citation2013). Further, older adults tend to prune off casual social relationships to focus on a small number of close ties (Carstensen et al., Citation1999) and attachment figures may change to include one or more adult children (Magai et al., Citation2016). The attachment system, with its central focus on emotion regulation and management of support-seeking from others, may have an important role in explaining individual resilience and thriving in the face of developmental challenges in later life.

An important question is whether attachment security changes over time, especially at older ages. Research is limited (Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2016, pp. 140–141), but the most credible evidence provided by panel studies suggests attachment patterns are trait-like, being reasonably stable in old age as well as across the adult life span (Chopik et al., Citation2019; Kirkpatrick & Hazan, Citation1994). Although results from cross-sectional studies about whether older people are more dismissing than younger people are mixed (cf. Chopik et al., Citation2013; Diehl et al., Citation1998), the best longitudinal evidence indicates that attachment insecurity—both anxiety and avoidance—tends to decline with age from mid-life to later life (Chopik et al., Citation2019). At the heart of attachment theory is the idea that working models are open to revision as a result of salient relational experiences, although the empirical evidence about how and when this occurs is still quite limited (Pietromonaco & Barrett, Citation2000). Relationship difficulties or break-ups have been shown to reduce attachment security (Davila et al., Citation1999; Kirkpatrick & Hazan, Citation1994) and attachment security has been shown to tend to increase within relationships characterized by warmth and lack of hostility as well as within marriages characterized by high relationship satisfaction (Davila et al., Citation1999; Dinero et al., Citation2008; Kirkpatrick & Hazan, Citation1994). Although therapeutic interventions often aim to encourage greater attachment security, empirical evidence is encouraging rather than definitive (Burgess Moser et al., Citation2016).

Despite the relevance of social relationships for health and quality of life, relatively little gerontological research has explored individual differences in older adults’ capacities to sustain high quality social relationships. From an attachment-theoretical perspective, internal working models of the other are thought to have a profound role in social relationships. One may anticipate that internal working models of the other may operate similarly in older adults as they do in younger and middle-aged adults, in which individuals with a positive other-model (secure and preoccupied types) tend to score higher on indicators of sociability and interpersonal understanding (Bartholomew & Horowitz, Citation1991; Diehl et al., Citation1998). However, evidence exploring whether adult attachment is related to older adults’ social networks or relationships is in its infancy: Chopik et al. (Citation2013, Citation2019) has reported lower anxiety and avoidance among older people who were in partnerships, just as for younger people.

A core tenet of attachment theory is that secure relationships provide a foundation for psychological well-being (Fraley, Citation2019). In this vein, a recent meta-analysis reported robust associations, among adults of all ages, between preoccupied and fearful attachment styles—both high on the anxiety dimension—and raised risk of anxiety and depression (Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2016, p. 398). In contrast, findings were inconsistent for dismissing attachment with many studies failing to observe effects (Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2016, p. 400). Evidence is building that adult attachment affects physical health: insecure individuals may experience physiological dysfunction in terms of cortisol and immune responses and in the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary system, ultimately leading to raised risk of cardiovascular and other chronic diseases (Diamond & Fagundes, Citation2010; Pietromonaco & Powers, Citation2015). Individuals high on the anxiety dimension may experience greater negative affect and stress, which are associated with inflammation and disease risk; those high on the avoidant dimension may have less health-promoting lifestyles and may delay healthcare seeking when ill (Ciechanowski et al., Citation2002; Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2016, p. 433; Pietromonaco & Beck, Citation2019). In terms of quality of life, attachment security may help people appraise potentially stressful situations as manageable, mobilize positive emotions in difficult times, foster flexible adjustment to changing life circumstances, and provide an accompanying sense of personal agency (Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2016, pp. 498–501). Empirical studies have observed associations between secure attachment and higher well-being, as well as with attachment deactivating strategies typical of avoidant attachment, this latter potentially resulting from bias in avoidant individuals’ reporting of their well-being (Van Assche et al., Citation2013).

Surprisingly, despite the potential importance of attachment style in this life phase for a wide range of outcomes, the gerontological literature exploring the impacts of adult attachment is relatively restricted (Bradley & Cafferty, Citation2001; Homan, Citation2018; Magai et al., Citation2016; Martin, Citation2018). Much of the existing empirical literature focusses on young adults; many studies of older adults have small sample sizes and take a cross-sectional approach. Larger studies specifically of older people would enable small to medium effects to be observed, such as those expected for dismissing attachment styles. Further, incorporating a lengthy follow-up period would provide information about the stability of the relationships between attachment and health and quality of life in this life phase.

The current study

We consequently seek to contribute to the literature by addressing the following research questions in a large, well-characterized, prospective cohort of older people:

Are adult attachment styles associated with mental health concurrently and 14 years later?

Are adult attachment styles associated with physical health concurrently and 14 years later?

Are adult attachment styles associated with quality of life five years later?

Examination of both cross-sectional and prospective associations will provide information about the stability of associations between adult attachment and health and quality of life outcomes as well as, indirectly, about the stability of the construct of adult attachment itself.

Materials and methods

Data

Data are drawn from the Whitehall II prospective cohort study (Marmot & Brunner, Citation2005). At recruitment in 1985/88 the participants were aged 35–55 and were working in 20 civil service departments in London. Participants provided written consent and the Whitehall II study was approved by the University College London ethics committee. The Swedish Ethical Review Authority approved the present study (Dnr: 2021-01351). The current analysis uses data obtained from postal questionnaires at phases 5 (1997–1999), 7 (2002–2004) and 11 (2012–2013).

Measures

Adult attachment

Adult attachment was measured at phase 5 with the Relationships Questionnaire (RQ, Bartholomew & Horowitz, Citation1991), a commonly used measure which has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity (Ravitz et al., Citation2010). The RQ is based on Bowlby’s internal working models of the self (worthy of love and support or not) and others (trustworthy and available or unreliable and rejecting). It is a four-quadrant model distinguishing four attachment styles: secure (the self as worthy, others generally accepting and responsive), preoccupied (the self as unworthy, positive evaluation of others), dismissive-avoidant (the self as worthy, negatively disposed to others) and fearful-avoidant (the self as unworthy, negatively disposed to others). Bartholomew and Horowitz adapted Hazan and Shaver’s (Citation1987) self-report procedure to create the RQ. After reading four short paragraphs describing the four attachment styles, respondents are asked to indicate from 0–100 the degree to which they resemble each of the four styles and are classified into the quadrant with the highest score to generate a four-category variable (cf. Appendix).

Health

Mental and physical health were measured at phases 5 and 11 using the General Health Questionnaire 30 (GHQ-30) and the Short Form 36 (SF-36). The GHQ-30 is designed to measure mental health symptoms in the general population (Goldberg & Williams, Citation1988). It is made up of 30 statements measuring mental state (in particular depressive mood, anxiety and sleep disturbance), social functioning, well-being and coping abilities. Example items are: ‘Been able to concentrate’, ‘Lost much sleep over worry’, and ‘Felt constantly under strain’. Items are scored on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (=less than usual) to 3 (=much more than usual), which generates a scale ranging from 0–90, where higher scores indicate poorer mental health.

SF-36 is an internationally validated measure of health functioning, which measures eight health concepts: bodily pain, general health perceptions, general mental health (psychological distress and well-being), physical functioning, limitations in usual role activities due to emotional problems, limitations in usual role activities due to physical health problems, social functioning and vitality (energy and fatigue) (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992). These health concepts can be summarized into the mental component summary (MCS) and the physical component summary (PCS), where higher scores indicate better health.

Quality of life

Subjective quality of life was measured using the CASP-19 scale, a validated measure designed for use among older adults in the general population (Hyde et al., Citation2003). The scale measures human needs that are particularly relevant in later life: control, autonomy, self-realization and pleasure, which together form the acronym CASP. Each of the 19 Likert-scaled items draws on one of these domains; example items being: ‘I feel free to plan for the future’, ‘I feel that my life has meaning’ and ‘I choose to do things that I have never done before’. The items are summed to generate a 0–57-point score in which higher scores represent better quality of life.

Quality of life was not available at waves 5 or 11; consequently, these analyses used quality of life at phase 7—the closest available phase—which took place five years after adult attachment was measured at phase 5.

Adjustment variables

Participants reported their age, gender and education level in the surveys. Education was collected in a three-category variable indicating the participant’s school-leaving age; we created an extra category ‘missing’ for participants lacking this information.

Analyses

The analyses were performed in R version 4.2.1 and Stata 17.0. We performed linear regressions, with and without adjustment variables (age, gender and education level), of adult attachment and the following health outcomes: GHQ-30, SF-36 PCS and MCS, as well as CASP-19 quality of life. Secure attachment served as the reference group.

In order to study these relationships in relation to time, we performed two sets of analyses for the mental and physical health outcomes. The first set of analyses were cross-sectional, measuring adult attachment and each outcome at phase 5; the second set of analyses were prospective, measuring the outcomes at phase 11, 14 years after adult attachment was measured. Analyses for the SF-36 subscales are presented in the appendix, following Ware and Kosinski’s recommendation to interpret results from MCS and PCS in parallel with the subscales (Ware & Kosinski, Citation2001).

Both phase and item non-response occur in the Whitehall II data. Consequently, sensitivity analyses were carried out with full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation using the lavaan package in R. Results from these analyses are presented in the appendix.

Participants

At phase 5 of Whitehall II, 7,870 individuals participated and 6,846 answered the RQ. In order to maximize the sample sizes in the face of both phase and item missingness in the Whitehall II study, we were maximally inclusive in creating samples. The sample sizes consequently vary across outcomes and phases, from 6,713 for GHQ-30 at phase 5 to 5,222 for SF-36 at phase 11. In the FIML sensitivity analyses the sample size was 6,846 for all outcomes.

Results

Descriptive findings

See for descriptive statistics. More than 70 percent of the Whitehall II sample is male; mean age was 56 years (SD: 6.0) at phase 5, 61 years at phase 7 and 70 years at phase 11. Almost half of the Whitehall II sample at phase 5 was classified into the secure attachment style. Of the other three types, classification into the dismissing style was most frequent (one-third of participants) and then preoccupied (13 percent) and lastly fearful (7 percent).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for the whole sample and by attachment style, Whitehall II phases 5, 7 and 11.

Gender was associated with attachment style (χ2(3) = 12.43, p = 0.006) but differences were small. The largest differences were that 12 percent of men compared to 15 percent of women were classified as having a preoccupied attachment style. Within the age range 44–68 years at wave 5, older participants were more likely to display dismissing attachment; younger participants preoccupied attachment (ANOVA, F(3) = 30.08, p < 0.001). Education was not associated with attachment style at the five percent significance level (χ2(9) = 16.01, p = 0.067).

Cross-sectional and prospective associations between adult attachment style and health and quality of life

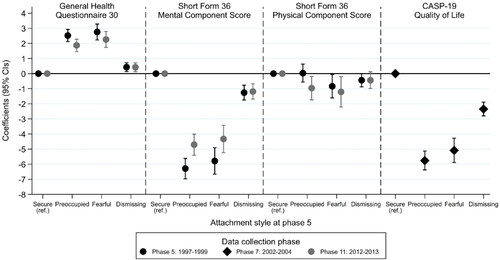

See for concurrent and longitudinal results, with and without inclusion of adjustment variables. Results for the SF-36 subscales at phases 5 and 11 are presented in in the appendix. Sensitivity analyses using FIML estimation are presented in in the appendix; these findings were similar to the main models. See for visual depiction of the adjusted models.

Figure 1. Associations between attachment styles and mental and physical health and quality of life, Whitehall II at phases 5, 7 and 11.

Note. Models are adjusted for age, gender and education level. Sample sizes are: for General Health Questionnaire 30, n = 6713 at phase 5 and n = 5322 at phase 11; for mental and physical component scores, n = 6628 at phase 5 and 5222 at phase 11; and n = 5929 for CASP-19 quality of life. Higher scores in the General Health Questionnaire indicate poorer mental health, while higher mental and physical component scores indicate better functioning and higher CASP-19 scores indicate better quality of life.

Table 2. Modelling of mental and physical health in relation to attachment style, Whitehall II.

In cross-sectional analyses at phase 5, fearful and preoccupied attachment styles were significantly associated with poorer mental health (as measured by both the GHQ-30 and the SF-36 MCS) compared to the secure attachment style. Scores on the GHQ-30 for the preoccupied and fearfully attached exceeded 4, indicating psychiatric caseness (in model 1 at phase 5, intercept for the secure style: 2.41; coefficient for the preoccupied style: 2.78 and for the fearful style: 2.82). The dismissing attachment style was also significantly associated with poorer mental health (as measured by both the GHQ-30 and the SF-36 MCS) compared to the secure attachment style, but effect sizes were substantially smaller. These findings were broadly similar for those SF-36 subscales relating more strongly to mental health—general mental health, role limits due to emotional problems, social functioning and vitality () (cf. Ware & Kosinski, Citation2001, ). There were only small changes in these results after inclusion of age, gender and education.

Turning to physical health, cross-sectional associations between attachment style and physical health were smaller and not always present. Absence of associations with the SF-36 PCS may be artefactual, resulting from a documented methodological quirk in which negative contributions from mental health subscales raise the PCS (Taft et al., Citation2001). Attachment style was associated with those SF-36 subscales that relate more strongly to physical health—bodily pain, general health perceptions, physical functioning and role limits due to physical problems (). Preoccupied and fearful attachment were associated with poorer physical health according to all four subscales, and dismissing attachment was associated, generally to a lesser degree, with poorer physical health for three of the four subscales (not for bodily pain, ). These findings were broadly similar after adjustment for age, gender and education.

Compared to the secure attachment style, fearful and preoccupied and, to a lesser degree, dismissing attachment styles were associated with lower quality of life at phase 7 (). Similar findings emerged from the models adjusted for age, gender and education. The differences by attachment in quality of life were large, overshadowing gender differences.

Turning to the 14-year follow-up, differences in mental and physical health functioning by attachment style were broadly similar to the cross-sectional associations. The exceptions were smaller associations in the case of the preoccupied attachment style for mental health, as measured by both the GHQ-30 and the SF-36 MCS, and less consistent associations with the SF-36 physical functioning subscale (cf. and A2).

Discussion

This paper demonstrates concurrent and 14-year-long longitudinal associations between adult attachment and a range of mental and physical health and quality of life outcomes. Our finding that fearful and preoccupied individuals are particularly vulnerable to poor health and quality of life are in line with prior research into the anxiety attachment dimension (Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2016, p. 398; Pietromonaco & Beck, Citation2019). Although prior research examining associations between the dismissing attachment style and health has been inconsistent (Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2016, p. 400), we were able to observe small associations between the avoidant-dismissing attachment style and most health and quality of life outcomes. We suspect that previous studies may have missed such effects due to small sample sizes and advocate for adequately powering studies in attachment research.

The observed associations between attachment security and health were reasonably similar between the cross-sectional analyses and the 14-year follow-up, a finding which suggests stability in the relationship between attachment style and health at this phase of the life course. Taking the reasoning one step further, the lack of impact of time passing suggests substantial stability in the concept of adult attachment itself in this phase of the life course, a finding that corresponds to initial longitudinal evidence that attachment orientation is a relatively stable disposition in adulthood (Chopik et al., Citation2019).

Effect sizes of adult attachment in relation to mental health and quality of life were large. In the case of GHQ-30, they were associated with levels of distress high enough to be classified as psychiatric caseness, which has the interpretation that if such respondents presented in general practice, they would likely receive further attention (Jackson, Citation2006). Adult attachment emerged as a novel and important predictor of CASP-19 quality of life, an indicator which measures the degree to which older adults are meeting their needs for independence, enjoyment and self-realization: core developmental challenges at this life stage. Future research could profitably explore the mechanisms lying behind the associations from adult attachment to CASP-19, in particular whether close relationships are the main cause (Fiori et al., Citation2011), and what the role might be for other factors such as self-esteem and sense of competence.

Most of the effects we observed concerned the anxiety dimension of attachment—relating to preoccupied and fearful attachment styles—which implies that difficulties with emotional health primarily concern individuals lacking a positive view of the self. These findings for emotional health correspond to theoretical ideas in which anxious attachment interferes with down-regulation of negative emotions, intensifying and prolonging distress (Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2016, p. 191). The smaller and often marginal associations with dismissing attachment have a variety of potential explanations. They point to the relative success of the dismissing approach to emotion regulation, in which emotional composure is restored through a strategy of suppression (Van Assche et al., Citation2013), as well as to a potential role for deficits in interoception (Ferraro & Taylor, Citation2021).

Although effects on physical health by attachment style were smaller than for mental health and quality of life, there was a suggestion of difficulties with physical health for individuals low in attachment security. In terms of lack of trust in others (fearful and dismissing), this finding is in line with earlier reports that individuals high on the avoidance dimension may be more likely to underutilize healthcare and maladaptively cope with stress through problematic substance use or disordered eating (Maunder & Hunter, Citation2008).

Implications

Our findings provide additional support for the importance of the attachment system for health and wellbeing in old age. They point to the importance of policies that not only support caregivers in sensitively meeting their children’s attachment needs, but also promote adults’ secure and mutually rewarding relationships with others, be they family, friends or romantic partners. They imply that policies supporting effective clinical interventions may contribute to the health and quality of life of older adults. Such interventions might include individual, couple or family therapies that enable insecure working models to be revised. These approaches may be particularly valuable in primary care settings and in nursing homes, as loneliness (as a basis for poor mental and physical health) may be easier to target when underlying cognitive mechanisms are addressed (Masi et al., Citation2011).

Limitations

This study has several strengths: its large sample size, prospective follow-up and specific focus on the young-old. However, there are some important limitations. First, information on adult attachment was collected using the RQ measurement instrument in 1997, a time when the modern dimensional approaches to measuring attachment with better psychometric properties had not yet been developed. Although the precision of such a categorical variable is lower than the underlying dimensions, the large sample size of the Whitehall II study enabled observation of small effects. A further critique of the RQ concerns its reliability (Ravitz et al., Citation2010), which suggests that the stability of the underlying concepts we are measuring may be even higher than we were able to observe. Second, Whitehall II is an occupational cohort of civil servants, which likely substantially underrepresents people with serious psychopathology. This may have led to an underestimation of the associations with health and quality of life of insecure attachment styles, particularly strongly for the fearful attachment style category which typically includes people with highly disrupted and traumatic childhoods. Third, while our findings suggest stability in adult attachment in old age, definitive evidence would be provided by a repeat measure of attachment. Unfortunately, despite their undoubted value for research, repeat measures over such lengthy timescales are typically absent from datasets that measure adult attachment, including from the Whitehall II data used in the current paper. Fourth, our findings suggest relationships between adult attachment and health and quality of life outcomes, but these relationships may not necessarily reflect cause and effect. Alternative explanations include confounding, in which an unmeasured third variable causes the observed relationship, or reverse causation, in which mental or physical health affects attachment style.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the important and stable role of adult attachment for mental health and quality of life in old age. It highlights the importance of inner representations of the self and others for difficulties with emotional health, in particular for individuals who lack a representation of the self as acceptable and worthy. These psychological processes may underlie some avoidable differences in health and wellbeing in later life.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants in the Whitehall II Study, Whitehall II researchers and support staff who make the study possible. The UK Medical Research Council (MR/K013351/1; G0902037), British Heart Foundation (RG/13/2/30098), and the US National Institutes of Health (R01HL36310, R01AG013196) have supported collection of data in the Whitehall II Study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no competing interests.

Data availability statement

Data, protocols and other metadata of the Whitehall II study are available to the scientific community via either the Whitehall II study data sharing portal at University College London or Dementias Platform UK (https://www.dementiasplatform.uk).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7(2), 147–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407590072001

- Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226–244.

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. New York: Basic Books.

- Bradley, M. J., & Cafferty, T. P. (2001). Attachment among older adults: Current issues and directions for future research. Attachment & Human Development, 3(2), 200–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730126485

- Burgess Moser, M., Johnson, S. M., Dalgleish, T. L., Lafontaine, M.-F., Wiebe, S. A., & Tasca, G. A. (2016). Changes in relationship-specific attachment in emotionally focused couple therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 42(2), 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12139

- Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. The American Psychologist, 54(3), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.165

- Chopik, W. J., Edelstein, R. S., & Fraley, R. C. (2013). From the cradle to the grave: Age differences in attachment from early adulthood to old age. Journal of Personality, 81(2), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00793.x

- Chopik, W. J., Edelstein, R. S., & Grimm, K. J. (2019). Longitudinal changes in attachment orientation over a 59-year period. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116(4), 598–611. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000167

- Cicirelli, V. G. (2010). Attachment relationships in old age. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(2), 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407509360984

- Ciechanowski, P. S., Walker, E. A., Katon, W. J., & Russo, J. E. (2002). Attachment theory: A model for health care utilization and somatization. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(4), 660–667. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200207000-00016

- Davila, J., Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1999). Attachment change processes in the early years of marriage. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(5), 783–802. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.5.783

- Diamond, L. M., & Fagundes, C. P. (2010). Psychobiological research on attachment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(2), 218–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407509360906

- Diehl, M., Elnick, A. B., Bourbeau, L. S., & Labouvie-Vief, G. (1998). Adult attachment styles: Their relations to family context and personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1656–1669. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1656

- Dinero, R. E., Conger, R. D., Shaver, P. R., Widaman, K. F., & Larsen-Rife, D. (2008). Influence of family of origin and adult romantic partners on romantic attachment security. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 22(4), 622–632. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012506

- Ferraro, I. K., & Taylor, A. M. (2021). Adult attachment styles and emotional regulation: The role of interoceptive awareness and alexithymia. Personality and Individual Differences, 173, 110641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110641

- Fiori, K. L., Consedine, N. S., & Merz, E.-M. (2011). Attachment, social network size, and patterns of social exchange in later life. Research on Aging, 33(4), 465–493. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027511401038

- Fraley, R. C. (2019). Attachment in adulthood: Recent developments, emerging debates, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102813

- Goldberg, D., & Williams, P. (1988). A user’s guide to the general health questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-NELSON Publishing Company Ltd.

- Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 511–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511

- Homan, K. J. (2018). Secure attachment and eudaimonic well-being in late adulthood: The mediating role of self-compassion. Aging & Mental Health, 22(3), 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1254597

- Hyde, M., Wiggins, R. D., Higgs, P. F. D., & Blane, D. (2003). A measure of quality of life in early old age: The theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19). Aging & Mental Health, 7(3), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360786031000101157

- Jackson, C. (2006). The general health questionnaire. Occupational Medicine, 57(1), 79–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kql169

- Kirkpatrick, L. A., & Hazan, C. (1994). Attachment styles and close relationships: A four-year prospective study. Personal Relationships, 1(2), 123–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1994.tb00058.x

- Magai, C., Frías, M. T., & Shaver, P. R. (2016). Attachment in middle and later life. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment (3rd ed., pp. 534–552). London: The Guilford Press.

- Marmot, M., & Brunner, E. (2005). Cohort profile: The Whitehall II study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 34(2), 251–256. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh372

- Martin, A. A. (2018). Secure attachment as a resource for healthy aging: Micro- and macro-longitudinal perspectives on attachment processes in adulthood and old age [PhD thesis]. University of Zurich. https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/166998

- Masi, C. M., Chen, H.-Y., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2011). A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 15(3), 219–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310377394

- Maunder, R. G., & Hunter, J. J. (2008). Attachment relationships as determinants of physical health. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry, 36(1), 11–32. https://doi.org/10.1521/jaap.2008.36.1.11

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2016). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change (2nd ed.). London: The Guilford Press.

- Pietromonaco, P. R., & Barrett, L. F. (2000). The internal working models concept: What do we really know about the self in relation to others? Review of General Psychology, 4(2), 155–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.4.2.155

- Pietromonaco, P. R., & Beck, L. A. (2019). Adult attachment and physical health. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 115–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.04.004

- Pietromonaco, P. R., & Powers, S. I. (2015). Attachment and health-related physiological stress processes. Current Opinion in Psychology, 1, 34–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.12.001

- Ravitz, P., Maunder, R., Hunter, J., Sthankiya, B., & Lancee, W. (2010). Adult attachment measures: A 25-year review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69(4), 419–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.08.006

- Taft, C., Karlsson, J., & Sullivan, M. (2001). Do SF-36 summary component scores accurately summarize subscale scores? Quality of Life Research : An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 10(5), 395–404.

- Van Assche, L., Luyten, P., Bruffaerts, R., Persoons, P., van de Ven, L., & Vandenbulcke, M. (2013). Attachment in old age: Theoretical assumptions, empirical findings and implications for clinical practice. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(1), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.003

- Ware, J. E., & Kosinski, M. (2001). Interpreting SF-36 summary health measures: A response. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 10(5), 405–413. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012588218728

- Ware, J. E., Jr, & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002

Appendix

Statements from the relationship questionnaire as used in Whitehall II

Secure: It is easy for me to become emotionally close to others. I am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t worry about being alone or having others not accept me.

Fearful-avoidant: I am uncomfortable getting close to others. I want emotionally close relationships, but I find it difficult to trust others completely, or to depend on them. I worry that I will be hurt if I allow myself to become too close to them.

Preoccupied: I want to be completely emotionally intimate with others, but I often find others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I am uncomfortable being without close relationships, but I sometimes worry that others don’t value me as much as I value them.

Dismissing-avoidant: I am comfortable without close emotional relationships. It is very important to me to feel independent and self-sufficient, and I prefer not to depend on others or have others depend on me.

Table A1. . Attachment styles in relation to the Short Form 36 subscales, Whitehall II, phase 5, n = 6628.

Table A2. Attachment styles in relation to the Short Form 36 subscales, Whitehall II, phase 11, n = 5222.

Table A3. Modelling of mental and physical health in relation to attachment style, Whitehall II, n = 6846. Full information maximum likelihood estimation.