Abstract

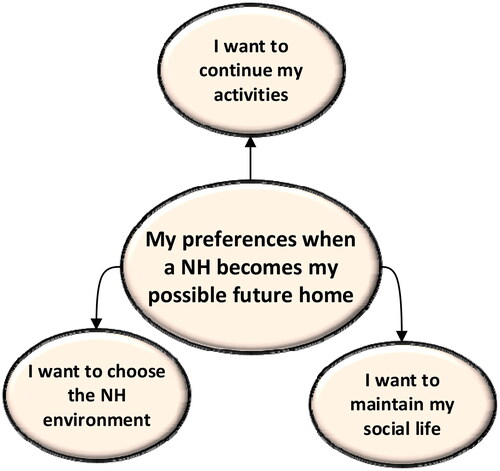

Introduction: Interprofessional collaboration (IPC) within and during movements between care settings is crucial for optimal palliative dementia care. The objective of this study was to explore the experiences of persons with dementia regarding collaboration with and between healthcare professionals (HCPs) and their perceptions of a possible future move to the nursing home (NH) in palliative dementia care. Method: We conducted a cross-sectional qualitative study and performed semi-structured interviews with a purposive sample of persons with dementia living at home (N = 18). Data analysis involved content analysis. Results: Our study demonstrated that even though most persons with dementia find it difficult to perceive the collaboration amongst HCPs, they could describe their perceived continuity of care (Theme 1. My perception of collaboration among HCPs). Their core needs in collaboration with HCPs were receiving information, support from informal caregivers, personal attention and tailored care (Theme 2. My needs in IPC). Regarding a possible future move to the NH, persons with dementia cope with their current decline, future decline and a possible future move to the NH (Theme 3. My coping strategies for a possible future move to the NH). They also prefer to choose the NH, and continue social life and activities in their future NH (Theme 4. My preferences when a NH becomes my possible future home). Conclusion: Persons with dementia are collaborative partners who could express their needs and preferences, if they are willing and able to communicate, in the collaboration with HCPs and a possible future move to the NH.

Introduction

Palliative care (PC) is defined as ‘the active holistic care of individuals across all ages with serious health-related suffering due to severe illness and especially of those near the end-of-life. It aims to improve the quality of life of patients, their families and their caregivers’ (Radbruch et al. Citation2020). PC is important to enhance the quality of life for persons with dementia (van der Steen, Radbruch, et al. Citation2014), since dementia is a life-limiting (Rait et al., Citation2010) and an incurable disease (Geldmacher et al., Citation2006). PC in dementia care may result in positive outcomes such as improved symptom management (Zahradnik & Grossman, Citation2014), and personalised care addressing holistic (physical, social, psychological, and spiritual) needs (Eisenmann et al., Citation2020; Perrar et al., Citation2015). As persons with dementia have holistic care needs (Perrar et al., Citation2015) and comorbidities (Guthrie et al., Citation2012), interprofessional collaboration (IPC) is one of the cornerstones of palliative dementia care (Davies et al., Citation2014; Ryan et al., Citation2012). IPC, described as a collaborative process between clients, informal caregivers and healthcare professionals (HCPs) (WHO, Citation2010), is necessary within and between care settings throughout the dementia care journey (Davies & Steen, Citation2018) to ensure continuity and quality of PC, and optimal information transfer (Bavelaar et al., Citation2021). Existing IPC approaches in palliative dementia care have been shown to reduce unmet needs (Samus et al. Citation2014); improve symptom management (Nakanishi et al., Citation2018); improve medication management (Sternberg et al., Citation2019); increase care satisfaction (Galvin et al., Citation2014); and increase quality of life (Samus et al. 2014).

The dementia journey is often characterised by several involved HCPs and during movements between care settings (Aaltonen et al., Citation2014; Callahan et al., Citation2012; Gill & Poss, Citation2011). Even though a person with dementia prefers to live (de Witt et al., Citation2010) and receive care at home (Prince et al., Citation2013), the move from home to the NH is a common event in dementia care (Smith et al., Citation2000). Continuous IPC is essential during care movements (Groenvynck et al., Citation2021; Groenvynck et al., Citation2022; Hirschman & Hodgson, Citation2018) in order to avoid fragmented care (Parry et al., Citation2003). Listening to the voice of persons with dementia as collaborative partners in care exceeds the principle of solely taking a person-centred approach (Dupuis et al., Citation2012) and enables them to contribute to collaborative activities (Hydén, Citation2014) such as decision-making (Daly et al., Citation2018). Previous studies have focused on the perceptions and needs of persons with dementia in the moving process to a NH, and the needs of persons with dementia in a NH after the move (Aminzadeh et al., Citation2010; Garvelink et al., Citation2019; Thein et al., Citation2011). These studies did not explore their thoughts about a possible future move to the NH. These prior studies plead that, because persons with dementia experience cognitive decline (Kramer & Duffy, Citation1996), timely preparation for a possible future move to the NH is imperative (Johnson, Citation2013) to identify their perspectives and preferences regarding a possible future move (Garvelink et al., Citation2019; Young et al., Citation2021). Our study addresses two research questions: 1) How do persons with dementia experience IPC with HCPs? and 2) How do persons with dementia perceive a possible future move to the NH?

Methods

Design and setting

We performed a qualitative cross-sectional study as part of the Desired Dementia Care Towards End of Life (DEDICATED) research project aiming to improve palliative dementia care (AWO, Citation2017). Semi-structured in-depth interviews were performed with community-dwelling individuals with dementia. The Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines were used to conduct the interviews and report the results (Supplement I) (Tong et al., Citation2007).

Housing and care in The Netherlands

In the Netherlands, there is a three-layered system: 1) Living at home with or without home care, 2) Living in shelter homes, and 3) Living in NHs (van Egdom, Citation1997). Dutch shelter homes can be described as apartments connected with the NH in which residents can receive services such as short-time care (van Egdom, Citation1997). Other housing options include care homes with different levels of support but without 24/7 care, and day care facilities that can be provided by NHs as respite service for informal caregivers (de Jong & Boersma, Citation2009; Rokstad et al., Citation2019; van Egdom, Citation1997).

Interview guide

The themes of the interview guide ‘IPC with professionals at home’ and ‘Possible future move to the NH’ (Supplement II) were based on a Dutch quality framework for PC (Boddaert et al., Citation2017), a white paper on palliative dementia care (van der Steen, Radbruch, et al. Citation2014), and a systematic review of end-of-life in dementia care (Perrar et al., Citation2015). These two themes are a subset of the integral interview guide on palliative dementia care, which also included future and end-of-life care. These topics were not included in this study, and the related manuscript of this study is published in the Journal of Clinical Nursing (Bolt et al., Citation2022). Preliminary questions were developed by three researchers (J.M.M., S.B., and S.P.) together with the DEDICATED research team, and validated by a working group consisting of nurses, dementia case managers, chain directors, policy makers, and patient representatives, which were informal caregivers of persons with dementia. The most important feedback that we processed was to make the questions shorter and easily understandable for the persons with dementia. After discussing the questions twice and reaching consensus, the interview guide was evaluated for feasibility through one pilot interview with a person with dementia and a patient representative.

Recruitment

We applied a criterion-based method () to recruit persons of 65 years and older with dementia who received care from home care organisations and NHs. The recruitment procedure aimed to include a heterogeneous group and followed a purposive sampling method, because it entailed a subjective sampling method, did not entail accidental sampling (Etikan & Babatope, Citation2019), and primarily focused on data saturation (Etikan, Citation2016). The recruiters were dementia case managers, geriatricians, and nurses from the care organisations participating in the DEDICATED project. The recruitment assessment was based on their expertise as HCPs, and their direct knowledge and relationship with the person with dementia. The researchers decided not to choose a scale to assess cognitive abilities since these scales do not often accurately reflect the communication skills of persons with dementia. Potential candidates were identified by clinical judgements of the recruiters about the cognitive capacities, communicative abilities and willingness of the person with dementia to participate with the interview. The recruiters provided eligible candidates and (if applicable) their informal caregivers information about the study objective and interview. They provided interested candidates and (if applicable) their informal caregivers a flyer and information letter, and asked for their consent to share their contact information with the researchers. Details about the recruitment procedure (Supplement III) are provided.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria.

Data collection

The interviews took place between September 2018 and October 2019 at the participants’ own homes. Two female members of DEDICATED were present at every interview, one of whom guided the interview. The other member observed and asked follow-up questions (Supplement IV). Interviews were audio recorded and all participants received a code to create anonymous transcripts. Prior to conducting the interviews, the interviewers were trained by a nurse specialist to ask questions understandably, provide the person with dementia sufficient time to answer the questions, and pay attention to their facial expressions. The transcripts were prepared in clean-read verbatim transcripts by a professional transcription service.

Data analysis

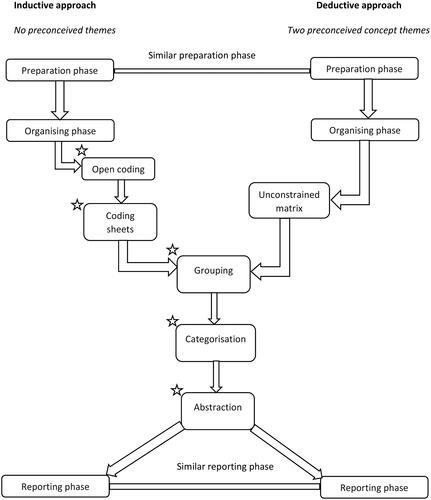

Transcripts were analysed using NVIVO version 11, and applying deductive and inductive approaches in the content analysis (Elo et al., Citation2014; Elo & Kyngas, Citation2008). The data analysis procedure is depicted in . We applied a deductive approach for the topic IPC at home because we developed two a priori themes based on previous studies that investigated the perceptions and experiences of (older) patients regarding IPC and described two layers of experiences, namely their perception of and their needs in IPC (Dahlke et al., Citation2018; Jarrett, Citation2009). We choose a deductive approach for this topic because we aimed to build further on these existing results about IPC but simultaneously further enrich our data by using an unconstrained matrix and thereby additionally developing inductive categories through grouping, categorisation and abstraction (Assarroudi et al., Citation2018). For the topic Possible future move to the NH, an inductive approach was applied because no prior research was conducted that captured the perceptions of older people concerning a possible future move. Therefore, we directly choose for open or initial coding to identify important units derived from the data itself to formulate codes and categories, and then organising the categories into themes for this topic (Erlingsson & Brysiewicz, Citation2017). Deductive and inductive coding were performed concomitantly. Two researchers analysed the data in chunks throughout four meetings to achieve optimal categorisation and abstraction of the data. Investigator-triangulation was employed to ensure the internal reliability of the data (Carter et al., Citation2014). The entire data analysis and saturation process is described in Supplement V and the coding tree is shown in Supplement VI. The results are described through key quotes from the participants, to whom we assigned pseudonyms.

Ethical considerations

Prior to conducting the interviews, written informed consent was obtained from persons with dementia or, if they were not capable from their informal caregivers. When informal caregivers signed the informed consent, the persons with dementia provided oral consent for their participation. We used pseudonyms to report the quotations of the participants. This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (WMA, Citation2013) and received confirmation from the Medical Ethics Committee Zuyderland that the Medical Research Involving Human Subject Acts did not apply (registration number METCZ20180085).

Results

Of the 22 candidates, four withdrew due to physical reasons, being overburdened or personal pursuits. The participants (N = 18) had a mean age of 82 years (range between 77-93) and 61% were men (). The majority lived at home (83%) and had informal caregivers (72%). The mean interview time was 53 min (SD = 19).

Table 2. Characteristics of persons with dementia (N = 18).

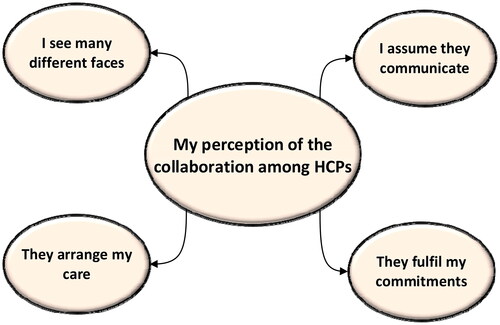

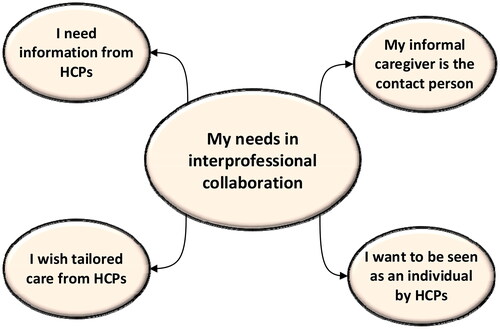

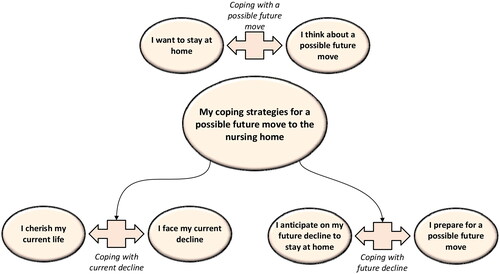

We identified the following four themes: 1) My perception of collaboration among HCPs (), 2) My needs in IPC (), 3) My coping strategies for a possible future move to the NH (), and 4) My preferences when a NH becomes my possible future home ().

Figure 2. Theme 1. My perception of collaboration among healthcare professionals. Abbreviations: HCPs = healthcare professionals.

Figure 3. Theme 2. My needs in interprofessional collaboration. Abbreviations: HCPs = healthcare professionals.

Figure 4. Theme 3. My coping strategies for a possible future move to the nursing home. Abbreviations: NH = nursing homes and o/a = or/and.

Figure 5. Theme 4. My preferences when a nursing home becomes my possible future home. Abbreviations: NH = nursing home.

Theme 1. My perception of collaboration among HCPs

Theme 1 describes the visibility of collaboration among HCPs and the impact on the care experience from the perspectives of persons with dementia ().

I see many different faces

Most participants could not identify all involved HCPs or identify the specific disciplines to which they belonged. However, most of them knew the faces or names of those who frequently provided care to them, under which the general practitioner, domestic workers and district nurses. Some of the participants mentioned that initially the presence of various HCPs gave them a chaotic or crowded feeling. ‘The peaceful life we had has become hectic.’ (Mr Henderson) However, as time passed, they became familiar with HCPs, got used to their involvement and enjoyed conversations with them.

I assume they communicate

The majority indicated that they did not know whether HCPs communicated with each other, but assumed that they did communicate. ‘I have the feeling that they meet each other weekly to talk about all the clients.’ (Mrs Newhouse) One participant noticed that HCPs often used the client file at home to communicate with each other. Two respondents said that they knew nothing about it. ‘It is up to them whether they want to communicate. That is not something I should interfere with.’ (Mr Jones)

They arrange my care

HCPs supported them in arranging their care process by contacting and involving other professionals or organisations. ‘My general practitioner had approached the municipality to apply for the Dutch Social Support Act so that we could receive support at home.’ (Mr Robinson) This support gave them a feeling of relief, because they knew that there was someone, apart from their informal caregiver, who took care of them. ‘It is reassuring to know that the right people are at the right place.’ (Mr Miller)

They fulfil my commitments

The interviewees experienced the overall collaboration among HCPs as optimal when HCPs executed care tasks according to their care preferences, were up-to-date, were on time and notified other HCPs who took over their shifts. ‘You do not have to wait for their arrival, they are always on time. And if someone is not able to come, they send someone else.’ (Mr Williams)

Theme 2. My needs in IPC

Theme 2 sums up the four main collaborative needs of persons with dementia ().

I need information from HCPs

The majority wanted to receive concise and simplified information about dementia and their overall health status. ‘I thought dementia: what is that? Is it Alzheimer? What phase? You have all these questions.’ (Mr Miller) A few also wanted to know the effects on their future life. One participant alluded to a support centre for informal caregivers where they received practical information about living with dementia. ‘It is important that the person with dementia and her or his informal caregivers are well informed about what is going on.’ (Mr Henderson) The majority did not want to know what HCPs discussed at team meetings, because they were not able to understand the information or were afraid to hear disturbing information. Two participants did want to participate themselves or designate informal caregivers to attend team meetings.

My informal caregiver is the contact person

Most interviewees had informal caregivers who assisted in the care process, communicated and made decisions on their behalf with HCPs. ‘I have limited contact with my dementia case manager, because my wife always talks with her. But afterwards my wife always tells me what they talked about.’ (Mr Thatcher) During the interviews, many participants referred to their informal caregivers when talking about how many HCPs were involved and how they collaborated with each other. They also mentioned that their informal caregiver was the contact person for HCPs, arranged the care process (together with HCPs) and monitored their appointments with HCPs for them.

I want to be seen as an individual by HCPs

All participants wanted to be seen as an individual with their own voice, and to maintain their independence for as long as they could. ‘The things I am able to do, I still want to do and I will do, and they should not tell me to do this and that.’ (Mr Jones) Almost all participants preferred having personal contact i.e. seeing familiar and friendly faces and taking the time to have (short) conversations.

I wish for tailored care from HCPs

According to persons with dementia, important HCPs’ competencies were having knowledge and a professional (proactive) attitude, and being skilled in executing care tasks. The majority was satisfied with their care; however, one participant explained that her general practitioner did not take her seriously: ‘She started to laugh and said it was nothing when I told her that my skin turned blue. But the other general practitioner told me that I had bruises because of the platelets, and that is why I had pain and felt nauseous.’ (Mrs Jackson) Most participants indicated that HCPs knew their preferences in the care process, such as when showering or receiving skin care. One participant mentioned that she was satisfied with the way nurses showered her. ‘I do not prefer to stand when they wash and dry me, so I sit on a chair in the bathroom.’ (Mrs Baker) Some participants mentioned how they appreciated if HCPs were interested in their personal life or had the same cultural background.

Theme 3. My coping strategies for a possible future move to the NH

Theme 3 specifies six coping strategies processed in three categories: coping with their current decline, coping with a possible future move to the NH and coping with future decline (). Every category portrays two coping strategies, which either have a reciprocal relationship (i.e. respondents use both strategies) or not (i.e. respondents apply one strategy but are aware of the other strategy).

Coping with current decline

I cherish my current life ⟺ I face my current decline

All participants cherished life by spending time with close persons and executing meaningful (daily) activities or hobbies, such as walking, playing darts and pool, or going to NH adult day care services. ‘I have always been an outdoorsman so every now and then I grab my bicycle.’ (Mr Fisher) Nonetheless, the majority was aware of their overall decline and the increasing number of care tasks that informal caregivers performed. In response, they made adaptations (for example writing down important information), took precautions and/or ceased certain activities. Six participants received personal care from formal caregivers and appreciated the assistance from HCPs, since they could continue with their life and could focus on things they could still do. However, they also often remembered and missed the times when they could take care of themselves.

Coping with a possible future move

I want to stay at home ⟺ I think about a possible future move

All participants wanted to stay at home for as long as possible to keep material and emotional attachments, and autonomy (i.e. freedom, uniqueness, privacy and independence). Material attachment meant living in their own house, with their informal caregivers and/or personal possessions and located in their familiar environment. Emotional attachment refers to their memories, their social interactions, and the feeling of being in charge of their life. Most referred to the NH as a place for the ‘end stage of life’ and described a possible future move to the NH as a threat because they were afraid to lose their meaningful life and autonomy. ‘You become just one of the other NH residents and do not have your own environment.’ (Mr Jones) Half of the participants did not want or were not able to think about a possible future move to the NH because they were not willing or able to imagine their future decline. ‘I do not wish to explore what I need to do when this or that happens.’ (Mr Brewer) Others, who were able or willing to imagine their future decline, mentioned the possibility of a possible future move. They preferred moving to a sheltered home due to their incremental decline and the burden on their informal caregivers. Two participants indicated their fear of being alone and realised their inability to maintain their house.

Coping with future decline

I anticipate my future decline to stay at home ⟺ I prepare for a possible future move

Half of the participants anticipated their future decline by seeking information and support, and adjusting their homes. Several of these participants were postponing the time to further think or talk about it as they saw it as an event in the far future. The minority, however, mentioned that they had let go of their wish to stay at home (i.e. ending the struggle to be independent, and enjoying receiving care), and also discussed and/or prepared for a possible future move (by, for example, performing NH visits). Two participants joined in day care centre activities at a sheltered home or a NH to get used to the new environment. ‘I visit the day-care centre twice a week to get a feeling how it would be to live there.’ (Mrs Damcott)

Theme 4. My preferences when a NH becomes my possible future home

Theme 4 describes what persons with dementia believe is important to feel at home in a NH ().

I want to choose the NH environment

Some participants said that they would prefer a NH in their familiar environment, close to their informal caregivers’ home, which contains familiar attributes such as having a garden, and provides a familiar feeling such as the presence of previous or current informal caregivers as residents. ‘As long as they do not send me to another city, because I come from *name town*, I know this environment.’ (Mr Miller)

I want to continue my activities

All participants wanted to maintain their daily activities or hobbies in NHs. For example, ‘I visited the sheltered homes and I could not say that it was terrible, but they said that they would not bring me to the church where I sing every week. But I really like to sing.’ (Mrs Damcott)

I want to maintain my social life

Participants find it important to remain connected with their informal caregivers, and have friendly HCPs and residents. ‘Harmony in contact with NH staff and with the other residents is important.’ (Mr Johnson)

Discussion

Overall, our study demonstrated that important needs of persons with dementia in collaboration with HCPs were receiving information, support from informal caregivers, personal attention and tailored care. Moreover, we showed that persons with dementia display six coping strategies when thinking about a possible future move and express three preferences when moving to a NH. The collaboration among HCPs at the process level was largely invisible to them. However, they could describe their perceived continuity of care. The collaboration needs we identified are concordant with previous studies demonstrating that many persons with dementia are still able to express their care preferences and expectations (Miller et al., Citation2016); request information about dementia (Prorok et al., Citation2013); and prefer skilled and respectful HCPs (Poole et al., Citation2018). Moreover, they want to be valued as individuals (Dahlke et al., Citation2017); and maintain dignity, autonomy, and self-respect (Bolt et al., Citation2022; van der Steen et al., Citation2011). Many of the abovementioned needs belong to important principles of PC (McInerney et al., Citation2018; Miller et al., Citation2016; Samsi & Manthorpe, Citation2013). The needs about a possible future home we described are also in line with previous studies, which investigated the needs of persons with dementia after making the decision to move to a NH: requesting a familiar environment (Lord et al., Citation2016), remaining able to perform meaningful activities (Davison et al., Citation2019), and establishing meaningful relationships (Shiells et al., Citation2020).

The fact that our study shows that persons with dementia wish to maintain their independence for as long as possible, continue with their activities, and maintain their social life is underlined by previous studies (Milte et al., Citation2016; Powers et al., Citation2016). This finding indicates that even though persons with dementia depend on informal caregivers and HCPs for preserving their personhood (Fetterolf, Citation2015) and executing several tasks (Smebye & Kirkevold, Citation2013), they are able to contribute to joint activities themselves (such as for example getting dressed) as collaborators (Hydén, Citation2014; Reed et al., Citation2017). A PC approach in an early dementia stage (Beernaert et al., Citation2016) could enable HCPs to proactively capture and deliver care according to these needs (Whitlatch & Orsulic-Jeras, Citation2018) before severe cognitive decline occurs (Radue et al., Citation2019).

With respect to the move to the NH, many persons with dementia wish to concentrate on the present (Poole et al., Citation2018) and perceive the move to the NH as the ‘end’ (Aminzadeh et al., Citation2009). However, some persons with dementia do realise their difficulties (Thein et al., Citation2011) and do not want to be a burden for their informal caregivers (Frank & Forbes, Citation2017). Our study showed that even though persons with dementia did not want to move to a NH, most of them were still able to express their needs to feel at home in a NH or to feel at home in their current environment. Therefore, it is crucial to regularly conduct personalised conversations by identifying coping strategies of persons with dementia (van der Steen, Soest-Poortvliet, et al. 2014) regarding a possible future move to the NH. Preparing the move enables informal caregivers and HCPs to identify the needs of persons with dementia in an early stage (Garvelink et al., Citation2019). This preparation could aid future decision-making (Samsi & Manthorpe, Citation2013) and preserve their relational and prospective autonomy (Bosisio et al., Citation2018). Since persons with dementia and their informal caregivers might accept a NH move more easily when their personal needs and difficulties are discussed, preparation through actually involving persons with dementia prior to the move could influence the way they feel in a NH (Thein et al., Citation2011) and improve familiarisation with the NH environment (Street & Burge, Citation2012). Furthermore, Brownie et al. (Citation2014) showed that persons involvement in the decision-making process regarding a care transition is pivotal to NH adjustment while keeping in mind that the needs and preferences of persons with dementia of course may change when their illness progresses making this a continuous dialogue (Brownie et al., Citation2014). It is important for HCPs to prepare for this move together with the person with dementia and their informal caregivers by organising NH visits, home visits and assembling information about the person’s life story, and current valuable routines and hobbies. This will help to become familiarised with the HCPs and NH, and is needed to build relationships and improve relational and prospective autonomy (Groenvynck et al., Citation2021). Building these relationships is crucial, as this could positively influence future NH experiences (Cater et al., Citation2022; van Hoof et al., Citation2016).

The importance of identifying the meaning of a move for persons with dementia was pinpointed by previous studies (Aminzadeh et al., Citation2009; Young et al., Citation2021). However, we additionally revealed coping strategies that HCPs may support in understanding the person with dementia, and adapting the conversation approach about a possible future move to the NH. Knowing collaborative and needs concerning a possible future move of persons with dementia in time could improve person-centred care; preserve identity; facilitate shared decision-making; and support in preparing for the move to the NH. These processes are described in the domains to provide optimal palliative dementia care (van der Steen, Radbruch, et al. 2014), and are mediated through IPC (Durand & Fleury, Citation2021; Legare et al., Citation2014; van der Steen, Soest-Poortvliet, et al. 2014). HCPs should take a collaborative approach in which they aim to include persons with dementia to hear their voice (Beard et al., Citation2009), and informal caregivers since they are advocators and proxy-decision makers (Hoek et al., Citation2021; Hoek et al., Citation2020). Moreover, different HCPs, such as for example dementia case managers (Garvelink et al., Citation2019), nurses (Bradway et al., Citation2012) or general practitioners (Stephan et al. Citation2018), could explore the thoughts and needs of persons with dementia regarding a possible future move, and transfer this information to HCPs from the NH. This collaborative approach may optimise person-centred information transfer (Davies et al., Citation2022) and coordination of the move (Ashbourne et al., Citation2021; McDonald et al., Citation2007).

Methodological considerations

The main strength of our study is that it captured the experiences and perspectives of persons with dementia living at home. Our study provides insight into how dementia affects people’s lives and shows how they process their thoughts about a possible future move by looking at their past, present and future. However, there are four limitations to consider when interpreting our results. First, during two interviews, a volunteer and dementia case manager were present, who sometimes interfered or asked questions themselves that might have influenced the responses of the participants. Second, there may have been sampling bias, because the recruiters selected candidates based on their clinical expertise and did not objectively measure the cognitive performance of persons with dementia. Therefore, we could not identify the severity of dementia of the participants. However, the aim of this study was to capture the experiences and needs of persons with dementia concerning IPC and a possible future move to the NH. Moreover, even though two persons with dementia displayed more advanced dementia symptoms, of which one participant had just moved to a NH, they were still able to express themselves and touched upon the same themes as the other participants. This finding that even though persons with dementia may show minor communication difficulties such as repetition, or memory difficulties such as not remembering whether they receive care, they still may provide insightful responses (Aminzadeh et al., Citation2009). This suggests that our findings may be include general themes that are applicable to persons with dementia during different stages, and inclusion of persons with dementia in research should consider a person-centred approach. Third, since 70% of the participants were men, our findings could compromise the generalisability of our findings. Our hypothesis is that perhaps in our study setting more men with dementia live at home because they are being taken care of by their female spouses, while women with dementia tend to end up in NHs more quickly than men do because women outlive men. This hypothesis is underlined by a Swedish study that mentioned that more men with dementia lived at home compared to women, while more women lived in NHs compared to men (Lethin et al., Citation2019). Lastly, we did not include persons with dementia living in a NH, whereas Mjørud et al. (Citation2017) showed that they are able to communicate their feelings and thoughts about living in a NH, and could identify factors that influence their quality of life in NHs (Mjørud et al., Citation2017).

Conclusion

Persons with dementia are able to express their needs and preferences as collaborative partners regarding the collaboration with HCPs and a possible future move to the NH. By sharing and respecting these needs and preferences, persons with dementia could engage in joint activities and thereby receive personalised PC. The coping strategies showed that most persons with dementia are willing and capable of realising their current and future decline, and half of them are open to conversations about a possible future move to the NH. Based on our findings, we recommend HCPs to proactively identify the needs, coping strategies and preferences of persons with dementia in an early phase, when they are willing and able to communicate.

Contribution statement

The authors JMM, SRB and JMGAS worked on the study design. SRB and SP mainly developed the interview list. CK and SRB conducted the interviews with persons with dementia and coded the data. CK initially interpreted the results, visualised the results in figures and prepared the manuscript. The authors JMM, JMGAS and DJAJ were involved in the final interpretation of the data, and revised the manuscript on content and layout. SRB performed a grammar and spelling check.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (98.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the persons with dementia for their participation in our study and healthcare professionals from the care organisations for their contribution in the recruitment procedure. We also thank Dr. Albine Moser (expert in qualitative research) for providing advice on the analysis method.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aaltonen, M., Raitanen, J., Forma, L., Pulkki, J., Rissanen, P., & Jylha, M. (2014). Burdensome transitions at the end of life among long-term care residents with dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 15(9), 643–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.04.018

- Aminzadeh, F., Dalziel, W. B., Molnar, F. J., & Garcia, L. J. (2010). Meanings, functions, and experiences of living at home for individuals with dementia at the critical point of relocation. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 36(6), 28–35. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20100303-02

- Aminzadeh, F., Dalziel, W. B., Molnar, F. J., & Garcia, L. J. (2009). Symbolic meaning of relocation to a residential care facility for persons with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 13(3), 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860802607314

- Ashbourne, J., Boscart, V., Meyer, S., Tong, C. E., & Stolee, P. (2021). Health care transitions for persons living with dementia and their caregivers. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 285. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02235-5

- Assarroudi, A., Heshmati Nabavi, F., Armat, M. R., Ebadi, A., & Vaismoradi, M. (2018). Directed qualitative content analysis: The description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. Journal of Research in Nursing: JRN, 23(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987117741667

- AWO. (2017). DEDICATED: Desired dementia care towards end of life. The living lab in ageing and long-term care. https://awo.mumc.maastrichtuniversity.nl/dedicated-desired-dementia-care-towards-end-life

- Bavelaar, L., Steen, H. T. A., Jong, H., Carter, G., Brazil, K., Achterberg, W., & van der Steen, J. (2021). Physicians’ perceived barriers and proposed solutions for high-quality palliative care in dementia in the Netherlands: Qualitative analysis of survey data. The Journal of Nursing Home Research Sciences, 7, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.14283/jnhrs.2021.5

- Beard, R., Knauss, J., & Moyer, D. (2009). Managing disability and enjoying life: How we reframe dementia through personal narratives. Journal of Aging Studies, 23(4), 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2008.01.002

- Beernaert, K., Deliens, L., Vleminck, A., Devroey, D., Pardon, K., Van den Block, L., & Cohen, J. (2016). Is there a need for early palliative care in patients with life-limiting illnesses? Interview study with patients about experienced care needs from diagnosis onward. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®, 33(5), 489–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909115577352

- Boddaert, M., Douma, J., Dijxhoorn, F., & Bijkerk, M. (2017). Netherlands quality framework for palliative care. IKNL/Palliactief.

- Bolt, S. R., van der Steen, J. T., Khemai, C., Schols, J., Zwakhalen, S. M. G., & Meijers, J. M. M. (2022). The perspectives of people with dementia on their future, end of life and on being cared for by others: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 31(13–14), 1738–1752. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15644

- Bosisio, F., Jox, R., Jones, L., & Truchard, E. (2018). Planning ahead with dementia: What role can advance care planning play? A review on opportunities and challenges. Swiss Medical Weekly, 148, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2018.14706

- Bradway, C., Trotta, R., Bixby, M. B., McPartland, E., Wollman, M. C., Kapustka, H., McCauley, K., & Naylor, M. D. (2012). A qualitative analysis of an advanced practice nurse-directed transitional care model intervention. The Gerontologist, 52(3), 394–407. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr078

- Brownie, S., Horstmanshof, L., & Garbutt, R. (2014). Factors that impact residents’ transition and psychological adjustment to long-term aged care: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(12), 1654–1666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.04.011

- Callahan, C. M., Arling, G., Tu, W., Rosenman, M. B., Counsell, S. R., Stump, T. E., & Hendrie, H. C. (2012). Transitions in care for older adults with and without dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(5), 813–820. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03905.x

- Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(5), 545–547. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.545-547

- Cater, D., Tunalilar, O., White, D. L., Hasworth, S., & Winfree, J. (2022). “Home is Home:” exploring the meaning of home across long-term care settings. Journal of Aging and Environment, 36(3), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/26892618.2021.1932012

- Dahlke, S., Meherali, S., Chambers, T., Freund-Heritage, R., Steil, K., & Wagg, A. (2017). The care of older adults experiencing cognitive challenges: how interprofessional teams collaborate. Canadian Journal on Aging = La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement, 36(4), 485–500. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980817000368

- Dahlke, S., Steil, K., Freund-Heritage, R., Colborne, M., Labonte, S., & Wagg, A. (2018). Older people and their families’ perceptions about their experiences with interprofessional teams. Nursing Open, 5(2), 158–166. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.123

- Daly, R. L., Bunn, F., & Goodman, C. (2018). Shared decision-making for people living with dementia in extended care settings: A systematic review. BMJ Open, 8(6), e018977. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018977

- Davies, K., & Steen, v. d. (2018). Palliative care in dementia. In R. D. MacLeod & L. Van den Block (Eds.), Textbook of palliative care (pp. 1–23). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31738-0_113-1

- Davies, M., Zúñiga, F., Verbeek, H., Simon, M., & Staudacher, S. (2022). Exploring interrelations between person-centred care and quality of life following a transition into long-term residential care: A meta-ethnography. Gerontologist, 63(4), 660–673. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnac027

- Davies, N., Maio, L., Vedavanam, K., Manthorpe, J., Vernooij-Dassen, M., & Iliffe, S., IMPACT Research Team. (2014). Barriers to the provision of high-quality palliative care for people with dementia in England: A qualitative study of professionals’ experiences. Health & Social Care in the Community, 22(4), 386–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12094

- Davison, T. E., Camões-Costa, V., & Clark, A. (2019). Adjusting to life in a residential aged care facility: Perspectives of people with dementia, family members and facility care staff. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(21-22), 3901–3913. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14978

- de Jong, J. D., & Boersma, F. (2009). Dutch psychogeriatric day-care centers: A qualitative study of the needs and wishes of carers. International Psychogeriatrics, 21(2), 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610208008247

- de Witt, L., Ploeg, J., & Black, M. (2010). Living alone with dementia: An interpretive phenomenological study with older women. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(8), 1698–1707. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05295.x

- Dupuis, S. L., Gillies, J., Carson, J., Whyte, C., Genoe, M., Loiselle, L., & Sadler, L. (2012). Moving beyond ‘patient’ and ‘client’ approaches: Mobilising authentic partnerships in dementia care. Dementia, 11(4), 427–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301211421063

- Durand, F., & Fleury, M.-J. (2021). A multilevel study of patient-centered care perceptions in mental health teams. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-06054-z

- Eisenmann, Y., Golla, H., Schmidt, H., Voltz, R., & Perrar, K. M. (2020). Palliative care in advanced dementia [review]. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 699. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00699

- Elo, S., & Kyngas, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. Sage Open, 4(1), 215824401452263. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014522633

- Erlingsson, C., & Brysiewicz, P. (2017). A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. African Journal of Emergency Medicine: Revue Africaine de la Medecine D’urgence, 7(3), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001

- Etikan, I. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Etikan, İ., & Babatope, O. (2019). A basic approach in sampling methodology and sample size calculation. Medlife Clinics, 1, 50–54.

- Fetterolf, M. (2015). Personhood-based dementia care: Using the familial caregiver as a bridging model for professional caregivers. Anthropology & Aging, 36(1), 82–100. https://doi.org/10.5195/aa.2015.84

- Frank, C., & Forbes, R. (2017). A patient’s experience in dementia care. Canadian Family Physician, 63, 22–26.

- Galvin, J. E., Valois, L., & Zweig, Y. (2014). Collaborative transdisciplinary team approach for dementia care. Neurodegenerative Disease Management, 4(6), 455–469. https://doi.org/10.2217/nmt.14.47

- Garvelink, M. M., Groen-van de Ven, L., Smits, C., Franken, R., Dassen-Vernooij, M., & Légaré, F. (2019). Shared decision making about housing transitions for persons with dementia: A four-case care network perspective. The Gerontologist, 59(5), 822–834. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny073

- Geldmacher, D. S., Frolich, L., Doody, R. S., Erkinjuntti, T., Vellas, B., Jones, R. W., Banerjee, S., Lin, P., & Sano, M. (2006). Realistic expectations for treatment success in Alzheimer’s disease. J Nutr Health Aging, 10(5), 417–429.

- Gill, S. S. C. X., & Poss, J. W. (2011). Community dwelling older adults with dementia. Health system use by frail Ontario seniors: An in-depth examination of four vulnerable cohorts (S. C. S. E. Bronskill, A. Gruneir, & M. M. Ho, Eds.). Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

- Groenvynck, L., de Boer, B., Hamers, J. P. H., van Achterberg, T., van Rossum, E., & Verbeek, H. (2021). Toward a Partnership in the transition from Home to a Nursing Home: The TRANSCIT Model. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 22(2), 351–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.09.041

- Groenvynck, L., Fakha, A., de Boer, B., Hamers, J. P. H., van Achterberg, T., van Rossum, E., & Verbeek, H. (2022). Interventions to improve the transition from home to a nursing home: A scoping review. The Gerontologist, 62(7), e369–e383. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab036

- Guthrie, B., Payne, K., Alderson, P., McMurdo, M. E. T., & Mercer, S. W. (2012). Adapting clinical guidelines to take account of multimorbidity. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 345, e6341. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e6341

- Hirschman, K. B., & Hodgson, N. A. (2018). Evidence-based interventions for transitions in care for individuals living with dementia. The Gerontologist, 58(suppl_1), S129–S140. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx152

- Hoek, L. J. M., Verbeek, H., de Vries, E., van Haastregt, J. C. M., Backhaus, R., & Hamers, J. P. H. (2020). Autonomy support of nursing home residents with dementia in staff-resident interactions: Observations of care. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(11), 1600–1608.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.04.013

- Hoek, L. J., van Haastregt, J. C., de Vries, E., Backhaus, R., Hamers, J. P., & Verbeek, H. (2021). Partnerships in nursing homes: How do family caregivers of residents with dementia perceive collaboration with staff? Dementia (London), 20(5), 1631–1648. 1471301220962235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301220962235

- Hydén, L.-C. (2014). Cutting Brussels sprouts: Collaboration involving persons with dementia. Journal of Aging Studies, 29, 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2014.02.004

- Jarrett, N. (2009). Patients’ experiences of inter-and intra-professional communication (IIPC) in the specialist palliative care context. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 8(1), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1515/IJDHD.2009.8.1.51

- Johnson. (2013). Relocation stress syndrome. Nursing diagnosis handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care (B. L. Ackley, G., Ed. 10th ed.). Mosby Elsevier.

- Kramer, J. H., & Duffy, J. M. (1996). Aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia in the diagnosis of dementia. Dementia (Basel, Switzerland), 7(1), 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1159/000106848

- Legare, F., Stacey, D., Briere, N., Robitaille, H., Lord, M. C., Desroches, S., & Drolet, R. (2014). An interprofessional approach to shared decision making: An exploratory case study with family caregivers of one IP home care team. BMC Geriatrics, 14(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-14-83

- Lethin, C., Rahm Hallberg, I., Vingare, E. L., & Giertz, L. (2019). Persons with dementia living at home or in nursing homes in nine Swedish urban or rural municipalities. Healthcare (Basel), 7(2), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7020080

- Lord, K., Livingston, G., Robertson, S., & Cooper, C. (2016). How people with dementia and their families decide about moving to a care home and support their needs: Development of a decision aid, a qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics, 16(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0242-1

- McDonald, K. M., Sundaram, V., Bravata, D. M., Lewis, R., Lin, N., Kraft, S. A., McKinnon, M., Paguntalan, H., & Owens, D. K. (2007). AHRQ technical reviews. In Closing the quality gap: A critical analysis of quality improvement strategies (Vol. 7: Care coordination). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US).

- McInerney, F., Doherty, K., Bindoff, A., Robinson, A., & Vickers, J. (2018). How is palliative care understood in the context of dementia? Results from a massive open online course. Palliative Medicine, 32(3), 594–602. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216317743433

- Miller, L. M., Whitlatch, C. J., & Lyons, K. S. (2016). Shared decision-making in dementia: A review of patient and family carer involvement. Dementia (London, England), 15(5), 1141–1157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301214555542

- Milte, R., Shulver, W., Killington, M., Bradley, C., Ratcliffe, J., & Crotty, M. (2016). Quality in residential care from the perspective of people living with dementia: The importance of personhood. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 63, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2015.11.007

- Mjørud, M., Engedal, K., Røsvik, J., & Kirkevold, M. (2017). Living with dementia in a nursing home, as described by persons with dementia: A phenomenological hermeneutic study. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2053-2

- Nakanishi, M., Endo, K., Hirooka, K., Granvik, E., Minthon, L., Nägga, K., & Nishida, A. (2018). Psychosocial behaviour management programme for home-dwelling people with dementia: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(3), 495–503. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4784

- Parry, C., Coleman, E. A., Smith, J. D., Frank, J., & Kramer, A. M. (2003). The care transitions intervention: A patient-centered approach to ensuring effective transfers between sites of geriatric care. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 22(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1300/J027v22n03_01

- Perrar, K. M., Schmidt, H., Eisenmann, Y., Cremer, B., & Voltz, R. (2015). Needs of people with severe dementia at the end-of-life: A systematic review. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD, 43(2), 397–413. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-140435

- Poole, M., Bamford, C., McLellan, E., Lee, R. P., Exley, C., Hughes, J. C., Harrison-Dening, K., & Robinson, L. (2018). End-of-life care: A qualitative study comparing the views of people with dementia and family carers. Palliative Medicine, 32(3), 631–642. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216317736033

- Powers, S. M., Dawson, N. T., Krestar, M. L., Yarry, S. J., & Judge, K. S. (2016). I wish they would remember that I forget:’ The effects of memory loss on the lives of individuals with mild-to-moderate dementia. Dementia (London, England), 15(5), 1053–1067. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301214553236

- Prince, M., Prina, M., & Guerchet, M. (2013). World Alzheimer Report 2013. Journey of Caring: An analysis of long-term care for dementia. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257482065

- Prorok, J. C., Horgan, S., & Seitz, D. P. (2013). Health care experiences of people with dementia and their caregivers: A meta-ethnographic analysis of qualitative studies. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de L’Association Medicale Canadienne, 185(14), E669–680. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.121795

- Radbruch, L., De Lima, L., Knaul, F., Wenk, R., Ali, Z., Bhatnaghar, S., Blanchard, C., Bruera, E., Buitrago, R., Burla, C., Callaway, M., Munyoro, E. C., Centeno, C., Cleary, J., Connor, S., Davaasuren, O., Downing, J., Foley, K., Goh, C., … Pastrana, T. (2020). Redefining palliative care-A new consensus-based definition. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(4), 754–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.027

- Radue, R., Walaszek, A., & Asthana, S. (2019). Neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. Handbook Clinical Neurology, 167, 437–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-804766-8.00024-8

- Rait, G., Walters, K., Bottomley, C., Petersen, I., Iliffe, S., & Nazareth, I. (2010). Survival of people with clinical diagnosis of dementia in primary care: Cohort study. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 341, c3584. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c3584

- Reed, P., Carson, J., & Gibb, Z. (2017). Transcending the tragedy discourse of dementia: An ethical imperative for promoting selfhood, meaningful relationships, and well-being. AMA Journal of Ethics, 19, 693–703. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.7.msoc1-1707

- Rokstad, A. M. M., McCabe, L., Robertson, J. M., Strandenæs, M. G., Tretteteig, S., & Vatne, S. (2019). Day care for people with dementia: A qualitative study comparing experiences from Norway and Scotland. Dementia (London, England), 18(4), 1393–1409. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301217712796

- Ryan, T., Gardiner, C., Bellamy, G., Gott, M., & Ingleton, C. (2012). Barriers and facilitators to the receipt of palliative care for people with dementia: The views of medical and nursing staff. Palliative Medicine, 26(7), 879–886. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216311423443

- Samsi, K., & Manthorpe, J. (2013). Everyday decision-making in dementia: Findings from a longitudinal interview study of people with dementia and family carers. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(6), 949–961. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610213000306

- Samus, Q. M., Johnston, D., Black, B. S., Hess, E., Lyman, C., Vavilikolanu, A., Pollutra, J., Leoutsakos, J.-M., Gitlin, L. N., Rabins, P. V., & Lyketsos, C. G. (2014). A multidimensional home-based care coordination intervention for elders with memory disorders: The maximizing independence at home (MIND) pilot randomized trial. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(4), 398–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2013.12.175

- Shiells, K., Pivodic, L., Holmerova, I., & Van den Block, L. (2020). Self-reported needs and experiences of people with dementia living in nursing homes: A scoping review. Aging & Mental Health, 24(10), 1553–1568. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1625303

- Smebye, K. L., & Kirkevold, M. (2013). The influence of relationships on personhood in dementia care: A qualitative, hermeneutic study. BMC Nursing, 12(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6955-12-29

- Smith, G. E., Kokmen, E., & O’Brien, P. C. (2000). Risk factors for nursing home placement in a population-based dementia cohort. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48(5), 519–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04998.x

- Stephan, A., Bieber, A., Hopper, L., Joyce, R., Irving, K., Zanetti, O., Portolani, E., Kerpershoek, L., Verhey, F., de Vugt, M., Wolfs, C., Eriksen, S., Rosvik, J., Marques, M. J., Goncalves-Pereira, M., Sjolund, B. M., Jelley, H., Woods, B., & Meyer, G, on behalf of the Actifcare Consortium. (2018). Barriers and facilitators to the access to and use of formal dementia care: Findings of a focus group study with people with dementia, informal carers and health and social care professionals in eight European countries. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0816-1

- Sternberg, S. A., Sabar, R., Katz, G., Segal, R., Fux-Zach, L., Grofman, V., Roth, G., Cohen, N., Radomyslaski, Z., & Bentur, N. (2019). Home hospice for older people with advanced dementia: A pilot project. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 8(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13584-019-0304-x

- Street, D., & Burge, S. W. (2012). Residential context, social relationships, and subjective well-being in assisted living. Research on Aging, 34(3), 365–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027511423928

- Thein, N. W., D’Souza, G., & Sheehan, B. (2011). Expectations and experience of moving to a care home: Perceptions of older people with dementia. Dementia, 10(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301210392971

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- van der Steen, J. T., Radbruch, L., Hertogh, C. M. P. M., de Boer, M. E., Hughes, J. C., Larkin, P., Francke, A. L., Jünger, S., Gove, D., Firth, P., Koopmans, R. T. C. M., & Volicer, L., European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC). (2014). White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: A Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliative Medicine, 28(3), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216313493685

- van der Steen, J. T., van Soest-Poortvliet, M. C., Achterberg, W. P., Ribbe, M. W., & De Vet, H. C. W. (2011). Family perceptions of wishes of dementia patients regarding end-of-life care. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(2), 217–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2577

- van der Steen, J. T., van Soest-Poortvliet, M. C., Hallie-Heierman, M., Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D., Deliens, L., de Boer, M. E., Van den Block, L., van Uden, N., Hertogh, C. M., & de Vet, H. C. (2014). Factors associated with initiation of advance care planning in dementia: A systematic review. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 40(3), 743–757. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-131967

- van Egdom, G. (1997). Housing for the elderly in the Netherlands: A care problem. Ageing International, 23(3–4), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-997-1012-3

- van Hoof, J., Verbeek, H., Janssen, B. M., Eijkelenboom, A., Molony, S. L., Felix, E., Nieboer, K. A., Zwerts-Verhelst, E. L., Sijstermans, J. J., & Wouters, E. J. (2016). A three perspective study of the sense of home of nursing home residents: The views of residents, care professionals and relatives. BMC Geriatrics, 16(1), 169. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0344-9

- Whitlatch, C., & Orsulic-Jeras, S. (2018). Meeting the informational, educational, and psychosocial support needs of persons living with dementia and their family caregivers. Gerontologist, 58, S58–S73. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx162

- WHO. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education & collaborative practice. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70185

- WMA. (2013). Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053

- Young, J. A., Lind, C., & Orange, J. (2021). A qualitative systematic review of experiences of persons with dementia regarding transition to long-term care. Dementia, 20(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301219862439

- Zahradnik, E. K., & Grossman, H. (2014). Palliative care as a primary therapeutic approach in advanced dementia: a narrative review. Clinical Therapeutics, 36(11), 1512–1517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.10.006