Abstract

Objective

The aim was to synthesise the current qualitative literature on the impact of Parkinson’s on the couple relationship, including individual and dyad studies.

Methods

Noblit and Hare’s meta-ethnography approach was applied; 19 studies were included in the review following a systematic search of four electronic databases. The studies included experiences of 137 People with Parkinson’s and 191 partners.

Findings

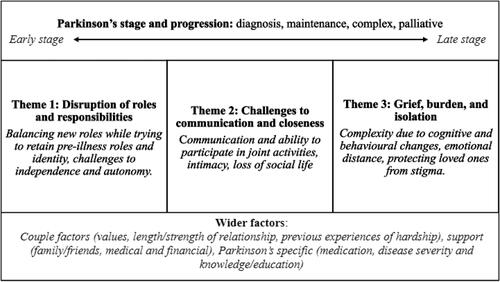

Analysis produced three themes: (1) Disruption of roles and responsibilities; (2) Challenges to communication and closeness; and (3) Grief, burden, and isolation. The themes are discussed with supporting extracts from the 19 included studies.

Conclusion

The findings highlight the challenges that couples experience and the individual and relational resources that support coping. Support should be individually tailored to each couple as the impact on the couple may change in response to individual and contextual factors. This review adds further evidence to the case for relationally focused multidisciplinary team input at all stages of Parkinson’s disease.

Background

Parkinson’s is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder, currently estimated to affect six million people worldwide (Dorsey et al. 2018). Although younger onset is possible, Parkinson’s typically develops over 50, its prevalence increases with age, and it is more common among males than females with a ratio of 1.5:1 (Pringsheim et al., Citation2014; Wooten et al., Citation2004). Parkinson’s is characterised by involuntary shaking of parts of the body, slowness in movement and stiff and inflexible muscles in the body and in the face, known as facial masking (DeMaagd & Philip, Citation2015). A range of other physical and psychological difficulties may also present, including anxiety, depression, loss of sense of smell, problems with balance and sleep disruption (Kobylecki, Citation2020). People with Parkinson’s (PWP) may also experience cognitive impairment, hallucinations, delusions, behaviour change, and dementia (Kobylecki, Citation2020). Disease stage and progression are commonly measured in clinical practice with the use of four stages, which include diagnosis, maintenance, complex, and palliative stages (Kobylecki, Citation2020), with a recognition that time spent within each phase may vary significantly. Treatments can manage the presenting symptoms and improve mobility, but become less effective over time and can cause unwanted side effects, including dyskinesia, and impulsive and compulsive behaviours (Weintraub et al., Citation2010).

PWP require increasing levels of care over time, a role often taken up by close relatives, many of whom are either a spouse or partner (DeMaagd & Philip, Citation2015). Much of the research on Parkinson’s has focused on either the needs of caregivers or of PWP exclusively, highlighting issues such as challenges related to caregiving and the impact of increasing dependence on PWP’s sense of autonomy and emotional well-being (Chen et al., Citation2021; Greenwell et al., Citation2015; Mosley et al., Citation2017; Perepezko et al., Citation2019; Theed et al., Citation2017; Vescovelli et al., Citation2018). However, illness not only impacts affected individuals and caregivers, but also the relationships between them (Rosland et al., Citation2012). Impact on the relationship can be exacerbated or mitigated by several factors, such as the severity of motor symptoms, psychological symptoms, reciprocity, and intimacy (Bertschi et al., Citation2021; Perepezko et al., Citation2019). A positive dyadic relationship, however, is said to mediate the effect of the burden associated with caregiving (Bertschi et al., Citation2021; Goldsworthy & Knowles, Citation2008; Mosley et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, higher rates of ‘mutuality’ are beneficial - a term used to encompass features that signify relationship quality including love and affection, shared pleasurable activities, shared values, and reciprocity (Archbold, Citation1992; Archbold et al., Citation1990). Increased mutuality between spouses and PWP was found to be associated with better mental health and improved quality of life in both partners, as well as reduced caregiver burden (Karlstedt et al., Citation2017; Tanji et al., Citation2008; Wielinski et al., Citation2010). Therefore, it seems likely the couple relationship can both affect, and be affected by, the experience of living with Parkinson’s. It is important to understand these effects in more detail to know how best to support PWP and their partners.

Previous qualitative reviews have explored the experiences of living with Parkinson’s from the point of view of the person with Parkinson’s (e.g. Rutten et al., Citation2021; Soundy et al., Citation2014) and their caregivers (e.g. Chen et al., Citation2021; Theed et al., Citation2017) separately, but the two perspectives have not been combined and the couple relationship has not been the focus. A recent scoping review by Weitkamp et al. (Citation2021) provided a helpful overview of pertinent issues relevant to dyadic coping in chronic illnesses, including Parkinson’s. However, the review considered a small number of both quantitative and qualitative studies, did not explore experiences in depth and did not include the experience of the caregiving partner.

Consequently, the current review aims to synthesise the available qualitative literature related to the experience of Parkinson’s and the couple’s relationship, including the perspective of both PWP and their caregiving spouse or partner. The research question that informed the review was ‘What is the impact of Parkinson’s on the couple’s relationship, and conversely, what is the impact of the couple’s relationship on the experience of Parkinson’s?’.

Method

Design

Meta-ethnography is an interpretive and inductive approach to qualitative synthesis developed by Noblit and Hare (Citation1988) and commonly used in qualitative health research. It seeks to provide a novel and interpretive account of the original papers. The current synthesis was influenced by Noblit and Hare (Citation1988) original works as well as more recent guidance (France et al., Citation2019; Sattar et al., Citation2021). The PRISMA guidelines (Page et al. 2021) guided the reporting of the search and the eMERGe guidelines (France et al., Citation2019) the reporting of the meta-ethnography overall.

Search strategy

The search constructed with an academic librarian combined 4 concepts: Parkinson’s AND couples/partners OR relationship satisfaction/quality AND qualitative research methods. It included both subject heading search terms and free text search terms (see supplementary material, Tables S1 and S2). Four academic databases were searched: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and Academic Search Ultimate. The search was conducted by the first author in November 2021 and repeated in March 2022, which enabled the inclusion of one further paper (Constant et al., Citation2022). Where it was unclear as to whether to include a paper, this decision was made in discussion with the second and fourth authors.

Table 1. Participant characteristics and research question.

Studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) were available in English; (2) were published in a peer-reviewed journal; (3) employed qualitative data collection and analysis methods; (4) Parkinson’s was the primary diagnosis; (5) findings were presented thematically or narratively, and the use of quotes provided evidence; and (6) results addressed to some degree the interplay between Parkinson’s and the couple relationship and involved either PWP, partners or spouses exclusively or studies which included both the perspective of PWP and their spouse or partner. Studies which included a research aim regarding caregiving experiences were not excluded, however, such papers were reviewed in full to determine whether the results included to any degree how caregiving experiences affected the relationship between PWP and caregiving partners. Where a small number of participants were not a spouse or partner, e.g. an adult child acting as a care partner, papers were included, but only findings that related to the couple’s relationship were included (Lawson et al., Citation2018; Roger & Medved, Citation2010; Thomson et al., Citation2020). No cut off dates were applied within the search.

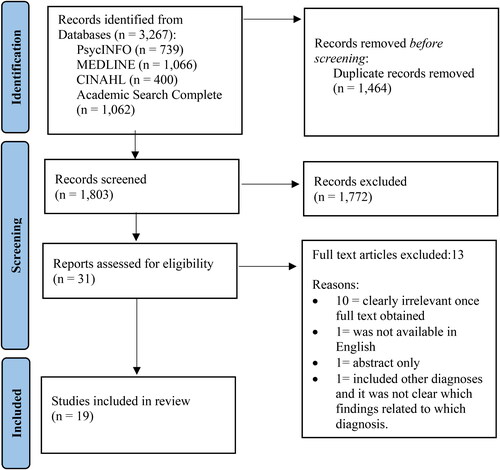

The database search returned 3,267 papers. Duplicates were removed (n = 1,464), and the remaining papers were reviewed by title and abstract. The full text of the papers deemed suitable (n = 31) were read, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. In total, 19 papers were identified that met the criteria for inclusion in the current review. Then the 19 studies’ reference sections were searched for any other relevant papers, and no further papers were identified. This process is illustrated within the PRISMA flow diagram in .

Quality appraisal

The papers were appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme for qualitative studies (CASP, Citation2018). This process highlighted methodological issues that were important to be aware of when including the study’s findings in the synthesis. Quality rating scores were applied using a system introduced by Duggleby et al. (Citation2010), whereby a score of 1–3 was given for each quality appraisal item on the CASP, which resulted in a total score out of 24 (see supplementary material, Table S3). Three papers were randomly selected for quality appraisal by an independent researcher and revealed an agreement in quality rating across the three papers. Papers scored within a range of 18–24 with the majority of papers being of high quality. Quality appraisal informed analysis by ensuring that papers which attained a lower quality rating informed the findings proportionately, with more weight placed upon papers which scored more highly.

Analysis and synthesis

The seven-step approach to meta-ethnography proposed by Noblit and Hare (Citation1988) informed the analysis. Themes were developed in an iterative process whilst repeatedly returning to the original texts to build an in-depth understanding of the studies’ content and meaning. Firstly, all 19 papers were read and re-read, and key themes and metaphors were identified and compared across papers. Next, all relevant second-order data were extracted along with relevant participant quotations and comparison was made across studies to identify similarities (reciprocal translations) and divergences (refutations). Several key concepts were identified through this process, which were then grouped to represent broader interpretations (details of the key concepts and broader interpretations (labelled conceptual clusters) can be seen in supplemental Table S4). A line of argument synthesis was developed, which allowed the bringing together of various aspects of the Parkinson’s experience to provide a new and dynamic narrative of the Parkinson’s experience from the couple’s point of view.

The authors took a critical realist stance when conducting the meta-ethnography, assuming our knowledge of reality is viewed through the lenses of our perceptions and beliefs (Barnett-Page & Thomas, Citation2009). The first author was a trainee clinical psychologist at the time of the analysis, the second author a clinical psychologist with expertise in chronic illness, the third author a consultant neurologist in movement disorders and the fourth author an academic clinical psychologist with expertise in Parkinson’s. Given the predominance of clinical psychologists, it is likely psychosocial issues would have been highlighted when analysing the data. However, the inclusion of a consultant neurologist on the team helped ensure that physical aspects of the experiences were not overlooked and that themes also resonated with his clinical experience. The analysis was predominantly conducted by the first author who extracted the data and synthesised the findings. However, she discussed each stage of the process with the second and fourth authors to ensure it was transparent and rigorous. The final themes were then discussed with the third author to ensure they were credible.

Results

Study characteristics

A summary of the participant characteristics for each study is contained in . The papers were published between 2000 and 2022. Studies took place in several continents including Europe, Australasia, North & South America. Eleven studies included both PWP and their spousal heterosexual or heterosexual romantic/cohabiting partner, seven studies included the spouse or partner of PWP exclusively, and one study included PWP exclusively (Fleming et al., Citation2004). Relationship duration also varied within and across studies, between 18 months and 64 years. One study included four PWP who had previously been in a relationship that had ended (Fleming et al., Citation2004). The studies included 137 PWP and 191 partners. A total of 83 PWP were male, and 54 were female. Of the partners, 147 were female, and 44 were male. Duration of Parkinson’s (where stated, n = 15) varied from one to 30 years. Further details of methods and individual study findings can be seen in supplementary material, Table S3.

Findings

Three themes were identified. These were as follows: (1) Disruption of roles and responsibilities; (2) challenges to communication and closeness; and (3) grief, burden, and isolation.

Theme 1: disruption of roles and responsibilities

A Parkinson’s diagnosis and changes in abilities to carry out daily activities resulted in changes in the distribution of domestic roles and responsibilities between couple members. This change resulted in relationship uncertainty and dissatisfaction for both PWP and their partners. The extent to which couples were impacted negatively by this change seemed to be influenced by several factors, such as values held within the pre-existing relationship, disease severity and the context in which couples resided. Couples described the use of individual and relationally focused methods of coping.

Due to people with Parkinson’s decreased physical and cognitive ability, partners were required to take on an increasing number of household tasks. Partners experienced a constant sense of responsibility: ‘I’ve had to take on all the responsibility, money, power of attorney, I have to do the maintenance.’ (Female, Partner) (Vatter et al., Citation2018, p. 608). The reallocation of domestic responsibilities represented a loss of role for people with Parkinson’s (Constant et al., Citation2022; Smith & Shaw, Citation2017). People with Parkinson’s who could no longer work experienced frustration at spending more time at home, feeling that they should go out to work to contribute to their family and household (Hodgson et al., Citation2004). Changes to the roles and responsibilities of people with Parkinson’s burgeoned a sense of redundancy, reduced confidence and dissatisfaction, the strain of which caused them to fear that their partners would leave them (Fleming et al., Citation2004; Martin, Citation2016).

I used to, you know, I didn’t wield a stick but you know I couldn’t, I could never do that, but I felt as though I had a position in the family, but now I don’t, I feel downgraded a bit, whether that’s paranoia setting in or not I don’t know but I just feel a lesser person … I feel as though she’s the boss now, really and it’s quite rightly is too because she’s got me to put up with, so there you are. (Male, PWP) (Lawson et al., Citation2018, p. 5).

Partners’ experienced a further role change due to their loved one’s need for care and support. However, the degree of change experienced differed between individuals. Some partners developed an in-depth knowledge of their loved one’s body and symptoms, whilst others viewed themselves as supporters, with their crucial role being to encourage independence and autonomy (Haahr et al., Citation2013; Habermann, Citation2000; Vatter et al., Citation2018). These differences seemed related to the nature of the relationship prior to Parkinson’s; for example, when couples had previously valued their independence, these values remained. In these cases, difficulties arose when the need for care outweighed the ability to retain independence. For example, when care needs were higher, some partners began to view their role as a caregiver rather than identifying as a partner (Thomson et al., Citation2020; Vatter et al., Citation2018). Partners recognised a need to stay physically close to their loved ones: ‘I must think about being close by. If I go out, I bring the mobile phone.’ (Male, Partner) (Haahr et al., Citation2013). For some, increased closeness represented a loss of independence and freedom.

However, couples’ experiences of Parkinson’s and the adjustments in couple roles and responsibilities seemed to be influenced by wider factors, such as the fluctuating nature of Parkinson’s meaning care and support needs were not linear, and increased stress in the context of financial strain, which resulted in some partners needing to continue working whilst also balancing the needs of their loved ones (Martin, Citation2016; Roger & Medved, Citation2010; Smith & Shaw, Citation2017).

Many couples described methods of coping with their change in roles and responsibilities. For example, finding meaning and purpose in their new roles as caregivers or cared for, or opportunities to share their learnings with others, for example, partners or people with Parkinson’s sharing their experiences with others in a support group setting (Habermann, Citation2000; Lawson et al., Citation2018). Couples described a wish to preserve their identities and autonomy by continuing with pre-diagnosis activities, which they felt, helped their relationship to thrive (Constant et al., Citation2022; Habermann, Citation2000; Hodgson et al., Citation2004; Mach et al., Citation2019; Roger & Medved, Citation2010; Smith & Shaw, Citation2017). Couples stressed the importance of finding a balance between people with Parkinson’s needs and the support provided so as not to disempower. Nevertheless, partners struggled to hold back and watch their loved one’s struggle (Constant et al., Citation2022; Habermann, Citation2000; Hodgson et al., Citation2004; Mach et al., Citation2019; Roger & Medved, Citation2010; Smith & Shaw, Citation2017).

Theme 2: challenges to communication and closeness

Symptom-related changes affected couples’ verbal and emotional communication and their ability to participate in activities they enjoyed together pre-diagnosis, affecting their sense of familiarity and togetherness. Whilst the pre-existing relationship was a source of strength and resilience, couples who managed to overcome such challenges experienced a strengthening of their relationship.

When symptom-related difficulties with verbal expressivity were experienced, couples’ communication reduced, which led to a sense of distance between them (Birgersson & Edberg, Citation2004; Mach et al., Citation2019; Vatter et al., Citation2018; Whitehead, Citation2010; Williamson et al., Citation2008; Wootton et al., Citation2019). Issues such as facial masking disrupted non-verbal communication, affecting couples’ ability to communicate emotionally. This lack of emotional reciprocity led to feelings of rejection, loss and disconnection for partners who worried their loved one was no longer satisfied with their relationship, which was painful for partners:

So I was getting angry… And yeah, and so I stopped talking. I stopped telling him stuff … because I thought he was disapproving or I thought that he was disinterested … Incredible loneliness for me. (Female, Partner) (Wootton et al., Citation2019, p.2520).

Furthermore, Parkinson’s symptoms and medication disrupted couples’ sexual intimacy due to changes in mobility or sexual drive, which for some was expected and viewed as a normal part of ageing (Fleming et al., Citation2004; Haahr et al., Citation2013; Habermann, Citation2000; Martin, Citation2016; Vatter et al., Citation2018). However, many couples, particularly those with younger onset Parkinson’s, found that reduced sexual intimacy strained their relationship (Martin, Citation2016; Vatter et al., Citation2018; Wootton et al., Citation2019).

Well, I think it’s just that, the changes that are happening are stressful on our relationship sometimes. He has all these health problems from Parkinson’s. He can’t sleep in bed. We are on different floors. He sleeps in a recliner. I sleep in the bedroom. It’s just kind of like, sometimes, it’s like we are roommates. (Female, Partner) (Martin, Citation2016, p. 235).

Throughout the challenges that Parkinson’s presented, the pre-existing couple relationship was a source of strength and resilience to cope: ‘When you’ve been married as long as we have, it takes a lot to shake things up’. (Female, Partner) (Martin, Citation2016, p. 232). Furthermore, pre-existing communication styles, problem-solving ability and evidence of overcoming previous challenges were also thought to influence couples’ coping (Haahr et al., Citation2013; Martin, Citation2016; Roger & Medved, Citation2010; Sánchez-Guzmán et al., Citation2022; Thomson et al., Citation2020). However, couples valued support and information from healthcare professionals, which helped them to develop an understanding of Parkinson’s signs and symptoms and develop skills which helped to maintain a positive relationship, such as alternative communication strategies and challenging negative thoughts and feelings that arose (Thomson et al., Citation2020; Wootton et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, when couples were able to overcome challenges, they seemed to experience a strengthening of their relationship: ‘the barriers have been broken down and we are closer’ (Female, Partner) (Habermann, Citation2000), in line with enhanced communication, understanding, appreciation, and a sense of resilience to cope with future challenges (Habermann, Citation2000; Roger & Medved, Citation2010; Wootton et al., Citation2019).

Theme 3: grief, burden, and isolation

Periods of enhanced need or complexity due to cognitive and behavioural changes, were a common theme among papers. Due to this, the partners’ experiences are highlighted more so than the perspective of PWP throughout this theme. However, this experience was relevant to the nature of the couple’s relationship; for example, emotional distance within the couple’s relationship at this stage was common. Nevertheless, partners continued to draw on the strength of their pre-existing relationship to continue caring for their loved ones.

Partners experienced loss and grief for their loved ones as their impairments grew. Furthermore, PWP had been their partner’s source of emotional support during times of challenge, which due to increased impairment, they were often no longer able to provide (Deutsch et al., Citation2021; Williamson et al., Citation2008). Partners also contended with the increasing weight of responsibility to care for their loved ones and to make decisions alone. As such, partners no longer viewed themselves as part of a mutually beneficial relationship (Deutsch et al., Citation2021; Lawson et al., Citation2018; Thomson et al., Citation2020; Vatter et al., Citation2018; Williamson et al., Citation2008; Wootton et al., Citation2019).

This man, this personality change he’s gone through, it’s crazy. It’s not—he’s not the man I married. He’s definitely not the man I married. He’s changed so much. If that’s just part and parcel of Parkinson’s, I guess? (Female, Partner) (Thomson et al., Citation2020, p. 2220).

Furthermore, behaviour changes such as jealous delusions were a significant challenge. Partners blamed themselves for these difficulties and felt they needed to be vigilant regarding their behaviours: ‘I had to be really careful that I didn’t trigger something that would upset him because he would become very upset.’ (Female, Partner) (Deutsch et al., Citation2021, p. 4). This led partners to experience a sense of exhaustion and a subsequent lack of energy to consider any actions that may help to maintain their relationship (Deutsch et al., Citation2021; Mach et al., Citation2019; McKeown et al., Citation2020). There was also evidence of a common perception that PWP lacked the care and interest to maintain the relationship at this stage which seemed to highlight a lack of understanding or capacity to empathise regarding the impact of Parkinson’s on their loved ones physical and cognitive abilities. Yet, this further fuelled partner’s sense of emotional distance (Constant et al., Citation2022).

Some partners described a wish to continue to protect their loved ones when impulsive and compulsive behaviours or delusional beliefs were present by explaining and justifying behaviours and symptoms or concealing these issues. Such coping methods meant that partners could not access the support they needed from family, friends, and healthcare professionals (Haahr et al., Citation2013; Deutsch et al., Citation2021; McKeown et al., Citation2020). Hesitancy to share openly and, therefore access support seemed to be connected to a wish to protect their loved ones but also due to shame or embarrassment regarding PWP symptoms and behaviours.

I couldn’t tell anybody about the violence and aggression or the pornography – my daughter would have been shocked and that is not the way I want him to be remembered. (Female, Partner) McKeown et al., Citation2020, p. 4628)

Overall, coping as a couple was markedly more challenging when cognitive and behavioural changes were dominant. However, partners employed several strategies to manage, such as externalisation of unwanted behaviours by focusing on them as part of the disease rather than their loved one’s character and the purposeful recall of more positive memories of their relationship (Deutsch et al., Citation2021; Mach et al., Citation2019; McKeown et al., Citation2020; Thomson et al., Citation2020; Vatter et al., Citation2018). Such strategies evidenced the source of strength that was the couple’s relationship, which partners could continue to draw on to support them in their caring role. At this stage, partners stressed the need to access external support such as respite care and enhanced support from friends and family (Deutsch et al., Citation2021; Lawson et al., Citation2018; Thomson et al., Citation2020). However, this needed to be considered carefully as, for some couples, separation further fuelled issues such as jealous delusions (Deutsch et al., Citation2021). Those who experienced shame and embarrassment valued being asked directly about behaviour change by health professionals or opportunities to access anonymous sources of support such as online support groups (McKeown et al., Citation2020).

Discussion

This review aimed to synthesise the available qualitative evidence about the experiences of Parkinson’s and the couple’s relationship. The themes expressed the impact of Parkinson’s on couples in terms of adjustment of their roles and responsibilities, how couples communicate and achieve closeness, and the impact of increased impairment and behavioural changes related to Parkinson’s. Throughout the themes were a number of wider factors that influenced the couple experience, including couple specific factors (values, length/strength of relationship, previous experiences of hardship), support (family/friends, medical and financial), and Parkinson’s specific factors (medication, disease severity and knowledge/education). Some findings seemed relevant to earlier stage disease, whereas others were more relevant to later stage disease, however, all issues seemed applicable across the spectrum of experience to a greater or lesser degree, in line with the heterogenous nature of Parkinson’s. The line of argument synthesis has been expressed in the image below ().

As expressed within Theme 1, for some couples, new roles and responsibilities caused by one couple member receiving a diagnosis, resulted in distress and relational dissatisfaction. Where possible, retaining a sense of autonomy for both partners and PWP was helpful. Encouraging independence and autonomy in PWP is suggested to support the maintenance of functional ability, well-being, and quality of life (Soundy et al., Citation2014; Zhao et al., Citation2021). As such, retaining ‘normalcy’ within the relationship was a relational endeavour that preserved individual well-being. Whilst simultaneously, individual coping methods, such as finding personal fulfilment and meaning within their new roles, and efforts to maintain one’s own identity by continuing with pre-Parkinson’s activities as far as possible, seemed to support their relational bond. Thus both intra- and inter-personal coping mechanisms supported both couple members with their role adjustments. This finding is in line with the dyadic-regulation connectivity model (DRCM; Karademas, Citation2022), which considers dyadic coping as a resource that fits alongside individual coping (Karademas, Citation2022). However, this study strengthens these understandings as applied to the field of Parkinson’s, as the fluctuating nature of Parkinson’s makes role adjustments and continuing with life as normal rather challenging. Furthermore, the nature of the pre-existing relationship and values held by the couple also influenced coping. Research on ‘we-ness’ suggests that couples who view illness as a collective experience have improved health and well-being (Rohrbaugh, Citation2021), and the extent to which this occurred often depended on the pre-illness relationship.

The second theme related to the challenges couples experienced, such as difficulties communicating and reduced ability to engage in activities. Such challenges impacted couples’ sense of closeness and caused uncertainty, dissatisfaction, and strained relationships. Firstly, difficulties with communication led to a dichotomy between PWP and partners. The cognitive transactional model (CTM; Badr & Acitelli, Citation2017), highlights the necessity for couples to be able to communicate their needs when attempting to cope with a stressor. This communication allows couples to view a stressor, such as illness, as a shared experience and thus support their coping, and difficulties with communication in Parkinson’s, reduced the shared experience.

Soundy et al. (Citation2014) suggests that seeing oneself as a member of a social group is a key factor influencing the well-being of PWP. The present review extends these suggestions suggesting that social identity as a couple is affected when Parkinson’s symptoms and concerns about stigma, prohibit couples’ usual functioning. However, benefit finding (Pakenham, Citation2010) was also seen, when couples found their relationship strengthened when they overcame challenges.

The third theme highlighted partners’ experiences related to the impact of increased impairment, psychological and cognitive changes, and changes in personality and behaviour. These experiences made PWP appear unlike themselves, which was associated with feelings of distress, loss, and grief for partners and a loss of their mutually beneficial relationship. In Parkinson’s, cognitive and psychological changes are suggested to have the most significant impact on couples’ estimations of mutuality (Archbold, Citation1992; Archbold et al., Citation1990; Karlstedt et al., Citation2017; Karlstedt et al., Citation2020), whereas higher rates of mutuality between spouses and PWP were found to be associated with the improved mental health of both partners, reduced caregiver burden and improved quality of life for both spouses and PWP (Karlstedt et al., Citation2017; Tanji et al., Citation2008; Wielinski et al., Citation2010). Therefore, it was not surprising to find that at this stage, partners experienced distress. However, partners experienced difficulties accessing the support they needed to cope, and it seemed to be interpersonal dynamics or relational issues which were central inhibitors of partners’ help-seeking behaviours. This further echoes the DCRM (Karademas, Citation2022), by highlighting the interconnection between the self, dyadic process and the wider context, such as the nature of the illness. However, this study goes further to add nuance and understanding as applied to the field of Parkinson’s, for example, the impact of cognitive and behavioural symptoms on dyadic processes.

Clinical implications

The present review suggests that a more systemic view of needs is needed, including the couple relationship. Guidance for care and supportive interventions for both PWP and carers has focused on individual rather than dyadic needs (e.g. Grimes et al. 2019; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Citation2017; Zarotti et al., Citation2021). This study suggests that enhanced multidisciplinary support for couples would benefit both couple and individual wellbeing. For example, increased focus on supporting couple communication and providing education about Parkinson’s including issues such as disease fluctuation, behavioural and cognitive symptoms to remain aware of, and when to seek advice and support, would ensure that couples can be prepared for the challenges and increase their resilience (Gamarel & Revenson, Citation2015).

There is currently little evidence for effective psychological interventions to support couples living with Parkinson’s. Preliminary suggestions have included support with problem-solving and facilitating role adjustment, as well as therapies such as narrative therapy, solution-focused therapy, and emotion-focused therapy (Beaudet & Ducharme, Citation2013; Haahr et al., Citation2020; Spencer & Haub, Citation2018). The evidence for psychological interventions for couples living with neurodegenerative conditions and other chronic illnesses is promising for the efficacy of behavioural interventions, emotionally focused couple therapy, narrative therapy, solution-focused therapy, and couple’s psychotherapy (Ghedin et al., Citation2017; Martire & Helgeson, Citation2017; Spencer & Haub, Citation2018; Vincent, Citation2019).

When considering enhanced coping, the pre-existing relationship and the values held by the couple influenced how they coped and what was deemed ‘normal’ to them. However, it was also identified that couple and individual wellbeing benefitted from ability to retain elements of one’s own pre-illness identity. Therefore, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes & Smith, Citation2005), may be a helpful approach to support these processes both when working with PWP and partners as couples or individuals. ACT, a talking therapy that supports patients to behave in ways which promote movement towards one’s values, draws on mindfulness and acceptance as skills to manage difficult and uncontrollable experiences (Hayes & Smith, Citation2005). ACT has been applied with individuals diagnosed with health conditions, carers and couples living with long term health conditions, such as HIV, cancer and chronic pain, to increase psychological flexibility, support adjustment, and help couples repair and rebuild their relationships (Graham et al., Citation2016; Hosseinpanahi et al., Citation2020; Potter et al., Citation2021).

Strengths and limitations

The current review provides an insight into the couple’s experience of Parkinson’s which is relevant for clinicians and researchers working with this patient group and their partners. To the authors’ knowledge this is the first paper to synthesise findings relating to the dyadic perspective. However, the perspective may have been broadened with the inclusion of grey literature, and the review includes papers published in English language only. There is a lack of diversity across participants’ views presented in this review in terms of ethnic background and sexual identity. Whereas the gender imbalance of studies (more males with Parkinson’s) was in line with estimations regarding Parkinson’s prevalence (Wooten et al., Citation2004), the findings presented may be weighted towards the female partner experience and male PWP experience. It is important to consider this gender bias within the reported findings as females with Parkinson’s are more likely to experience poorer quality of life compared to males (Crispino et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, the identification of papers and data extraction was largely led by one person (the first author), although frequent discussions were had with other authors and the researcher maintained a reflexive approach throughout (Atkins et al., Citation2008).

Future research

Further areas for research include couples’ experiences of Parkinson’s in diverse populations. Exploration of couples’ experiences at specific points of the disease trajectory, such as diagnosis experience, or during the complex stage would be helpful. As the partners’ perspective of later stage disease were dominant within this study, it would be helpful to seek the perspective of PWP of the couple relationship in the later stages. Longitudinal research would be helpful to see the impact of changes over time on the couple’s relationship as the disease progresses. Finally, research to consider the efficacy of specific therapies (e.g. ACT) would provide evidence for the provision and funding for couples’ interventions or interventions with a relational focus within Parkinson’s services.

Conclusion

This review adds further evidence to the case for relationally focused multidisciplinary care in Parkinson’s and explores the relevance of the couple’s relationship to many dimensions of the Parkinson’s experience. This review highlights the source of strength and resource for coping that the couple relationship represents that deserves to be preserved. Understanding the needs of the couple in addition to individual needs, presents a further fruitful area for multidisciplinary care teams to provide targeted support. Further research is needed to understand relational dimensions at discreet junctures within Parkinson’s and evidence for effective couples interventions.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (34.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Archbold, P. G., Stewart, B. J., Greenlick, M. R., & Harvath, T. A. (1992). The clinical assessment of mutuality and preparedness in family caregivers to frail older people. In S. G. Funk, E. M. Tornquist, M. T. Champagne, R. A. Wiese (Eds.), Key aspects of elder care: Managing falls, incontinence, and cognitive impairments (pp. 328–39). Springer.

- Archbold, P. G., Stewart, B. J., Greenlick, M. R., & Harvath, T. (1990). Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Research in Nursing & Health, 13(6), 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770130605

- Atkins, S., Lewin, S., Smith, H., Engel, M., Fretheim, A., & Volmink, J. (2008). Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: Lessons learnt. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-21

- Badr, H., & Acitelli, L. K. (2017). Re-thinking dyadic coping in the context of chronic illness. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 44–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.001

- Barnett-Page, E., & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9(1), 59–59. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-59

- Beaudet, L., & Ducharme, F. (2013). Living with moderate-stage Parkinson disease: Intervention needs and preferences of elderly couples. The Journal of Neuroscience Nursing: Journal of the American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, 45(2), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNN.0b013e3182828ff4

- Bertschi, I. C., Meier, F., & Bodenmann, G. (2021). Disability as an Interpersonal Experience: A Systematic Review on Dyadic Challenges and Dyadic Coping When One Partner Has a Chronic Physical or Sensory Impairment. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 624609. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.624609

- Birgersson, A. M. B., & Edberg, A. K. (2004). Being in the light or in the shade: Persons with Parkinson’s disease and their partners’ experience of support. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 41(6), 621–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.01.007

- Chen, Y., Zhou, W., Hou, L., Zhang, X., Wang, Q., Gu, J., Zhang, R., & Yang, H. (2021). The subjective experience of family caregivers of people living with Parkinson’s disease: A meta-ethnography of qualitative literature. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(5), 959–970. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-021-01995-9

- Constant, E., Brugallé, E., Wawrziczny, E., Sokolowski, C., Manceau, C., Flinois, B., Baille, G., Luc, D., Dujardin, K., & Antoine, P. (2021). Relationship Dynamics of Couples Facing Advanced-Stage Parkinson’s Disease: A Dyadic Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 770334. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.770334

- Crispino, P., Gino, M., Barbagelata, E., Ciarambino, T., Politi, C., Ambrosino, I., Ragusa, R., Marranzano, M., Biondi, A., & Vacante, M. (2020). Gender Differences and Quality of Life in Parkinson’s Disease. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010198

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). (2018). CASP Qualitative Checklist. http://www.casp-uk.net/checklists.

- DeMaagd, G., & Philip, A. (2015). Parkinson’s Disease and Its Management: Part 1: Disease Entity, Risk Factors, Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, and Diagnosis. P & T: A Peer-Reviewed Journal for Formulary Management, 40(8), 504–532.

- Deutsch, C. J., Robertson, N., & Miyasaki, J. M. (2021). Psychological Impact of Parkinson Disease Delusions on Spouse Caregivers: A Qualitative Study. Brain Sciences (2076–3425), 11(7), 871. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11070871

- Dorsey, E. R., Elbaz, A., Nichols, E., Abbasi, N., Abd-Allah, F., Abdelalim, A., Adsuar, J. C., Ansha, M. G., Brayne, C., Choi, J.-Y J., Collado-Mateo, D., Dahodwala, N., Do, H. P., Edessa, D., Endres, M., Fereshtehnejad, S.-M., Foreman, K. J., Gankpe, F. G., Gupta, R., … Murray, C. J. L. (2018). Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Neurology, 17(11), 939–953. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30295-3

- Duggleby, W., Holtslander, L., Kylma, J., Duncan, V., Hammond, C., & Williams, A. (2010). Metasynthesis of the hope experience of family caregivers of persons with chronic illness. Qualitative Health Research, 20(2), 148–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732309358329

- Fleming, V., Tolson, D., & Schartau, E. (2004). Changing perceptions of womanhood: Living with Parkinson’s disease. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 41(5), 515–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2003.12.004

- France, E. F., Cunningham, M., Ring, N., Uny, I., Duncan, E. A. S., Jepson, R. G., Maxwell, M., Roberts, R. J., Turley, R. L., Booth, A., Britten, N., Flemming, K., Gallagher, I., Garside, R., Hannes, K., Lewin, S., Noblit, G. W., Pope, C., Thomas, J., … Noyes, J. (2019). Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: The eMERGe reporting guidance. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0600-0

- Gamarel, K. E., & Revenson, T. A. (2015). Dyadic adaptation to chronic illness: The importance of considering context in understanding couples’ resilience. In K. Skerrett & K. Fergus (Eds.), Couple resilience: Emerging perspectives (pp. 83–105). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9909-6_5

- Ghedin, S., Semi, A., Caccamo, F., Caldironi, L., Marogna, C., Piccione, F., Stabile, R., Lorio, R., & Vidotto, G. (2017). Emotionally focused couple therapy with neurodegenerative diseases: A pilot study. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 45(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2016.1223562

- Goldsworthy, B., & Knowles, S. (2008). Caregiving for Parkinson’s disease patients: An exploration of a stress-appraisal model for quality of life and burden. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63(6), P372–376. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/63.6.P372

- Graham, C. D., Gouick, J., Krahé, C., & Gillanders, D. (2016). A systematic review of the use of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) in chronic disease and long-term conditions. Clinical Psychology Review, 46, 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.009

- Greenwell, K., Gray, W. K., Van Wersch, A., Van Schaik, P., & Walker, R. (2015). Predictors of the psychosocial impact of being a carer of people living with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 21(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.10.013

- Grimes, D., Fitzpatrick, M., Gordon, J., Miyasaki, J., Fon, E. A., Schlossmacher, M., Suchowersky, O., Rajput, A., Lafontaine, A. L., Mestre, T., Appel-Cresswell, S., Kalia, S. K., Schoffer, K., Zurowski, M., Postuma, R. B., Udow, S., Fox, S., Barbeau, P., & Hutton, B. (2019). Canadian guideline for Parkinson disease. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de L’Association Medicale Canadienne, 191(36), E989–E1004. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.181504

- Haahr, A., Kirkevold, M., Hall, E. O. C., & Østergaard, K. (2013). ‘Being in it together’: Living with a partner receiving deep brain stimulation for advanced Parkinson’s disease—A hermeneutic phenomenological study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(2), 338–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06012.x

- Haahr, A., Norlyk, A., Hall, E., Hansen, K. E., Østergaard, K., & Kirkevold, M. (2020). Sharing our story individualised and triadic nurse meetings support couples adjustment to living with deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 15(1), 1748361. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2020.1748361

- Habermann, B. (2000). Spousal perspective of Parkinson’s disease in middle life. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31(6), 1409–1415. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01457.x

- Hayes, S., & Smith, S. (2005). Get out of your mind and into your life: The new acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications.

- Hodgson, J. H., Garcia, K., & Tyndall, L. (2004). Parkinson’s disease and the couple relationship: A qualitative analysis. Families Systems & Health, 22(1), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/1091-7527.22.1.101

- Hoehn, M. M., & Yahr, M. D. (1967). Parkinsonism: Onset, progression and mortality. Neurology, 17(5), 427–442. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.17.5.427

- Hosseinpanahi, M., Mirghafourvand, M., Farshbaf-Khalili, A., Esmaeilpour, K., Rezaei, M., & Malakouti, J. (2020). The effect of counseling based on acceptance and commitment therapy on mental health and quality of life among infertile couples: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 9(1), 251–251. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_512_20

- Karademas, E. C. (2022). A new perspective on dyadic regulation in chronic illness: The dyadic regulation connectivity model. Health Psychology Review, 16(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2021.1874471

- Karlstedt, M., Fereshtehnejad, S. M., Aarsland, D., & Lökk, J. (2017). Determinants of dyadic relationship and its psychosocial impact in patients with Parkinson’s disease and their spouses. Parkinson’s Disease, 2017, 4697052–4697059. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4697052

- Karlstedt, M., Fereshtehnejad, S. M., Aarsland, D., & Lökk, J. (2020). Mediating effect of mutuality on caregiver burden in Parkinson’s disease partners. Aging & Mental Health, 24(9), 1421–1428. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1619165

- Kobylecki, C. (2020). Update on the diagnosis and management of Parkinson’s disease. Clinical Medicine (London, England), 20(4), 393–398. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2020-0220

- Lawson, R. A., Collerton, D., Taylor, J.-P., Burn, D. J., & Brittain, K. R. (2018). Coping with cognitive impairment in people with Parkinson’s disease and their carers: A qualitative study. Parkinson’s Disease, 2018, 1362053. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1362053

- Mach, H., Baylor, C., Hunting Pompon, R., & Yorkston, K. (2019). Third-party disability in family members of people with communication disorders associated with Parkinson’s disease. Topics in Language Disorders, 39(1), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1097/TLD.0000000000000172

- Martin, S. C. (2016). Relational issues within couples coping with Parkinson’s disease: Implications and ideas for family-focused care. Journal of Family Nursing, 22(2), 224–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840716640605

- Martire, L. M., & Helgeson, V. S. (2017). Close relationships and the management of chronic illness: Associations and interventions. The American Psychologist, 72(6), 601–612. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000066

- McKeown, E., Saleem, T., Magee, C., & Haddad, M. (2020). The experiences of carers looking after people with Parkinson’s disease who exhibit impulsive and compulsive behaviours: An exploratory qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(23–24), 4623–4632. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15499

- Mosley, P. E., Moodie, R., & Dissanayaka, N. (2017). Caregiver burden in Parkinson disease: A critical review of recent literature. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 30(5), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988717720302

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2017). Parkinson’s disease in adults (NG71). Nice.

- Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography synthesising qualitative studies. SAGE.

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Pakenham, K. (2010). Benefit-finding and sense-making in chronic illness. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195375343.013.0013

- Perepezko, K., Hinkle, J. T., Shepard, M. D., Fischer, N., Broen, M., Leentjens, A., Gallo, J. J., & Pontone, G. M. (2019). Social role functioning in Parkinson’s disease: A mixed-methods systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(8), 1128–1138. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5137

- Potter, K. J., Golijana-Moghaddam, N., Evangelou, N., Mhizha-Murira, J. R., & Das Nair, R. (2021). Self-help acceptance and commitment therapy for carers of people with multiple sclerosis: A feasibility randomised controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 28(2), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-020-09711-x

- Pringsheim, T., Jette, N., Frolkis, A., & Steeves, T. D. (2014). The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 29(13), 1583–1590. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.25945

- Roger, K. S., & Medved, M. (2010). Living with Parkinson’s disease—Managing identity together. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 5(2), 5129. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v5i2.5129

- Rohrbaugh, M. (2021). Constructing we-ness: A communal coping intervention for couples facing chronic illness. Family Process, 60(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12595

- Rosland, A. M., Heisler, M., & Piette, J. D. (2012). The impact of family behaviors and communication patterns on chronic illness outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 35(2), 221–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-011-9354-4

- Rutten, S., van den Heuvel, O. A., de Kruif, A. J. T. C. M., Schoonmade, L. J., Schumacher, E. I. M., Vermunt, K., Hagen, R., van Wegen, E. E. H., & Rutten, K. (2021). The subjective experience of living with Parkinson’s disease: A meta-ethnography of qualitative literature. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease, 11(1), 139–151. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-202299

- Sánchez-Guzmán, M. A., Paz-Rodríguez, F., Espinola Nadurille, M., & Trujillo-De Los Santos, Z. (2022). Intimate partner violence in persons with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(3–4), 1732–1748. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520920862

- Sattar, R., Lawton, R., Panagioti, M., & Johnson, J. (2021). Meta-ethnography in healthcare research: A guide to using a meta-ethnographic approach for literature synthesis. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-06049-w

- Smith, L. J., & Shaw, R. L. (2017). Learning to live with Parkinson’s disease in the family unit: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of well-being. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy, 20(1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-016-9716-3

- Soundy, A., Stubbs, B., & Roskell, C. (2014). The experience of Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. ScientificWorldJournal, 2014, 613592. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/613592

- Spencer, C., & Haub, M. (2018). Family therapy with couples and individuals with Parkinson’s Disease. Contemporary Family Therapy, 40(4), 299–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-018-9458-x

- Tanji, H., Anderson, K. E., Gruber-Baldini, A. L., Fishman, P. S., Reich, S. G., Weiner, W. J., & Shulman, L. M. (2008). Mutuality of the marital relationship in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 23(13), 1843–1849. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.22089

- Theed, R., Eccles, F., & Simpson, J. (2017). Experiences of caring for a family member with Parkinson’s disease: A meta-synthesis. Aging & Mental Health, 21(10), 1007–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1247414

- Thomson, C. J., Segrave, R. A., Racine, E., Warren, N., Thyagarajan, D., & Carter, A. (2020). ‘He’s back so i’m not alone’: The impact of deep brain stimulation on personality, self, and relationships in Parkinson’s disease. Qualitative Health Research, 30(14), 2217–2233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732320951144

- Vatter, S., McDonald, K. R., Stanmore, E., Clare, L., McCormick, S. A., & Leroi, I. (2018). A qualitative study of female caregiving spouses’ experiences of intimate relationships as cognition declines in Parkinson’s disease. Age and Ageing, 47(4), 604–610. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy049

- Vescovelli, F., Sarti, D., & Ruini, C. (2018). Subjective and psychological well-being in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 138(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.12946

- Vincent, C. (2019). Illness, couples and couple psychotherapy. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 35(4), 628–641. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjp.12501

- Weintraub, D., Koester, J., Potenza, M. N., Siderowf, A. D., Stacy, M., Voon, V., Whetteckey, J., Wunderlich, G. R., & Lang, A. E. (2010). Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: A cross-sectional study of 3090 patients. Archives of Neurology, 67(5), 589–595. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2010.65

- Weitkamp, K., Feger, F., Landolt, S. A., Roth, M., & Bodenmann, G. (2021). Dyadic coping in couples facing chronic physical illness: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 722740. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.722740

- Whitehead, B. (2010). The psychosocial impact of communication changes in people with Parkinson’s disease. British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 6(1), 30–36. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjnn.2010.6.1.46056

- Wielinski, C. L., Varpness, S. C., Erickson-Davis, C., Paraschos, A. J., & Parashos, S. A. (2010). Sexual and relationship satisfaction among persons with young-onset Parkinson’s disease. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(4 Pt 1), 1438–1444. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01408.x

- Williamson, C., Simpson, J., & Murray, C. D. (2008). Caregivers’ experiences of caring for a husband with Parkinson’s disease and psychotic symptoms. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 67(4), 583–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.04.014

- Wooten, G. F., Currie, L. J., Bovbjerg, V. E., Lee, J. K., & Patrie, J. (2004). Are men at greater risk for Parkinson’s disease than women? Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 75(4), 637–639. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2003.020982

- Wootton, A., Starkey, N. J., & Barber, C. C. (2019). Unmoving and unmoved: Experiences and consequences of impaired non-verbal expressivity in Parkinson’s patients and their spouses. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(21), 2516–2527. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1471166

- Zarotti, N., Eccles, F. J. R., Foley, J. A., Paget, A., Gunn, S., Leroi, I., & Simpson, J. (2021). Psychological interventions for people with Parkinson’s disease in the early 2020s: Where do we stand? Psychology and Psychotherapy, 94(3), 760–797. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12321

- Zhao, N., Yang, Y., Zhang, L., Zhang, Q., Balbuena, L., Ungvari, G. S., Zang, Y. F., & Xiang, Y. T. (2021). Quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 27(3), 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.13549