Abstract

Objectives: Drawing from the mindfulness framework and the broaden-and-build theory, this study investigates the extent to which mindfulness influences loneliness and whether the relation is mediated by positive and negative affect.

Method: Data were collected from 748 retired older adults aged 60 and above in Chengdu, China in 2022. Loneliness and mindfulness were measured by the UCLA loneliness scale and by the short-form version of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, while the positive and negative affect was assessed by the International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule.

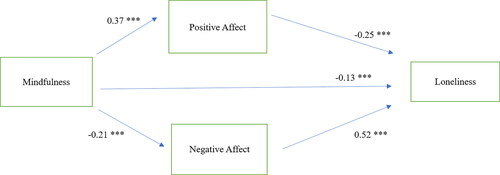

Results: The results of this study show that mindfulness was positively associated with positive affect (β = 0.37, p<.001), negatively related to negative affect (β=-0.21, p<.001) and loneliness (β=-0.13, p<.001), and had an indirect effect on loneliness via positive and negative affect (β=-0.20, p<.001).

Conclusion: The findings suggest that mindfulness could be a positive resource for improving mental health and reducing loneliness among retired older adults in China.

Introduction

Loneliness is a state of mind characterized by the perception of being alone and a discrepancy between desired and actual social relations, regardless of the amount of social contact that an individual experiences (Peplau & Perlman, Citation1982). The extent of loneliness is one of the key indicators of well-being in older adults. Empirical evidence has showed that loneliness is related to poor cognitive and health outcomes among older adults, including cognitive impairment, mistreatment, physical health, perceived stress, and depression (Cacioppo et al., Citation2006; Dong et al., Citation2007; Domènech-Abella et al., Citation2017; Hawkley et al., Citation2010; Huang et al., Citation2019; Zhou et al., Citation2019). Because of its harmful impacts on health and well-being, loneliness among older adults warrants rigorous examination to better understand how its effects can be mitigated.

The overall prevalence of loneliness in older adults ranges from 16% to 30%, depending on study samples, measures, and time periods (Simon et al., Citation2014; Srivastava et al., Citation2021; Sunwoo, Citation2020; Yang & Victor, Citation2008). Studies have found that the extent of loneliness in older adults varies by personal and environmental factors. Older adults who are female, older, live alone, have low educational attainment, have poor health, and are retired tend to report greater loneliness than their counterparts (Domènech-Abella et al., Citation2017; Dong & Chen, Citation2017; Simon et al., Citation2014; Srivastava et al., Citation2021; Yang & Victor, Citation2008). For example, Srivastava et al. (Citation2021) showed that retired individuals had greater loneliness (18.7%) than working old adults (13.5%) in an Indian sample. Dong and Chen (Citation2017) found that Chinese women had a higher rate (28.3%) of loneliness than older men (23.3%; p < .001). With respect to environmental factors, family functioning, social networks and support, sense of community, and location all appear to be important protective factors against loneliness in older adults (Srivastava et al., Citation2021; Wu et al., Citation2010; Yang & Victor, Citation2008). High social networking and support (Srivastava et al., Citation2021; Sunwoo, Citation2020; Wu et al., Citation2010), as well as high family function and sense of coherence (Huang et al., Citation2019; Wu et al., Citation2010), are significantly associated with low loneliness. Additionally, living in a rural area is associated with higher likelihood of loneliness than living in an urban area (Srivastava et al., Citation2021; Yang & Victor, Citation2008).

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a state of consciousness during which an individual actively engages in purposeful awareness and attention to the present moment, while also maintaining non-judgmental reactions to their observations (Kabat-Zinn, Citation1990). Mindfulness has trait-like properties in that it varies among individuals and from moment to moment (Bishop et al., Citation2004; Hülsheger et al., Citation2013). Empirical studies have examined the relation between mindfulness and loneliness in old adults, suggesting that mindfulness may reduce loneliness (Creswell et al., Citation2012; Moradizadeh, Citation2019) and improve mental health and life quality (Ghadampour et al., Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2022; Lindayani et al., Citation2020; O’Connor et al., Citation2014). Indeed, studies, largely based on data collected from adult samples, have shown that mindfulness can improve emotional adaption to promote positive affect and reduce negative affect, and that high positive affect and lower negative affect can reduce stress and loneliness (Mandal et al., Citation2012; Medvedev et al., Citation2021; Perez-Blasco et al., Citation2016; Tumminia et al., Citation2020). These studies suggest that mindfulness can reduce loneliness via positive and negative affect; in other words, positive and negative affect act as mediators in the relation between mindfulness and loneliness. However, the generalizability of these findings to older adults, who face challenges unique to their particular stage of the life course, is unknown, suggesting a need for empirical studies that focus on older adults specifically.

Positive affect and negative affect (PANA)

Positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) are important elements of subjective well-being (Diener & Emmons, Citation1984). PA refers to positive moods or emotions, such as optimism, confidence, and flexibility, while NA describes negative moods or emotions, like anxiety, fear, and guilt (Bradley et al., Citation2011; Lyubomirsky et al., Citation2005). The broaden-and-build theory posits that PA may broaden momentary thought-action repertoire, that is, momentary thought would spark the urge to action, such as feeling joy sparks the urge to engage and play (Fredrickson & Fowler, Citation2001; Garland et al., Citation2010). PA expands cognition and behavioral repertoires, and enable people to accumulate physical, psychological, and social resources that are instrumental in achieving positive accomplishments, such as performance and health, and coping mental health challenges such as loneliness (Cheung et al., Citation2022; Fredrickson & Fowler, Citation2001; Garland et al., Citation2010; Gloria & Steinhardt, Citation2016; Lyubomirsky et al., Citation2005). NA, on the other hand, reduces thought-action repertoire and prevents people from obtaining the resources they need for improving performance and health, thereby increasing their risk of negative physical and mental health outcomes (Bradley et al., Citation2011; Chen et al., Citation2020; Garland et al., Citation2010; Jonas & Lando, Citation2000; Wilkes et al., Citation2013). Empirical studies have also shown that mindfulness increases the extent of PA while it reduces level of NA (Ding et al., Citation2021; Gawrysiak et al., Citation2018; Medvedev et al., Citation2021; Snippe et al., Citation2015). For instance, Medvedev et al. (Citation2021), with data collected from the general population and a student population (n = 400), found that mindfulness is positively related to positive affect and mental health and negatively related to negative affect. In addition, studies have provided evidence that PA and NA were related to the extent of loneliness (Davidson et al., Citation2022; He et al., Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2017; Neto, Citation2014; Teneva & Lemay, Citation2020; van Roekel et al., Citation2015). For example, using 428 older adults in the United States, Davidson et al. (Citation2022) found that higher PA was associated with lower loneliness and that higher NA was related to higher loneliness. Taken together, these studies show that PANA plays substantial roles in shaping cognition, behavior, and well-being (Weiss, Citation2002; Zacher & Rudolph, Citation2021; Zhang & Han, Citation2016), and could serves as a potential mediator between mindfulness and loneliness (Lindsay et al., Citation2019; Medvedev et al., Citation2021; Pandya, Citation2021).

Retired older adults in China

The average retirement age in China is one of the youngest in the world. Although it can vary by gender and job, for men, the retirement age is currently set at 60 years old. For female civil servants, it is 55 years old, and for other female employees, it is 50 years old (Zhang et al., Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2023). Consequently, across the world, China has one of the largest populations of retired older adults. In 2021, 132 million retirees received social insurance benefits (Ministry of Human Resources & Social Security, 2022). In Chengdu, the capital of the southwestern Chinese province Sichuan and the fourth largest city in the country, retirees totaled 2 million in 2020 (Chengdu Human Resources & Social Security Bureau, 2021). Retirement is a major life event that may have substantial effects on the psychological well-being of older adults, though the effects of retirement vary by personal and environmental characteristics (Li et al., Citation2021; Kim & Moen, Citation2002; Stenling et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2011; Zhang & Zhang, Citation2015). Though current scholarship has shown that mindfulness has effects on mental health via PANA in older adults, the current state of knowledge on PANA’s mediating effects between mindfulness and loneliness among retired and older adults in China is limited. This is the focus of this study. If the findings of this study support the mediating role of PANA between mindfulness and loneliness, the findings may provide empirical evidence for the broaden-and-build theory in older adults in China and contribute to the understanding of how mindfulness affects loneliness through PANA in a rapidly developing retired population, especially in the context of earlier retirement ages, and can shed light on potential policy and practice that may improve the outcomes of this population. These findings can additionally be useful for the basis of research on mindfulness-based policy and practice in other countries that are similarly experiencing unprecedented growth in their older populations. For example, while the growth of the aging population in China is greater than those of many high-income countries in Europe and North America (Feng et al., Citation2020), the number of Americans older than 65 years old is projected to almost double between 2018 and 2060 (from 52 million to 95 million), going from accounting for 16% to 23% of the country’s population (Population Reference Bureau, 2019). The Chinese context thus serves as fertile ground for understanding the mechanism between mindfulness and loneliness in a country that has been experiencing—and will continue to experience—rapid growth in its aging population.

Conceptual model and hypotheses

The conceptual model of this study is based on mindfulness framework and the broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson & Fowler, Citation2001; Garland et al., Citation2010; Kabat-Zinn, Citation1990). We conceptualize mindfulness as enabling factor for older adults’ engagement in awareness without judgment, which in turn improves their emotional adaption from moment to moment and therefore broadens PA and lowers NA. This allows them to build and accumulate physical, psychological, and social resources that can reduce the extent of their loneliness. That is, PANA serves as mediators between mindfulness and loneliness. This conceptual model is illustrated in . Specifically, we hypothesize that:

Mindfulness is positively associated with PA.

Mindfulness is negatively associated with NA.

Mindfulness is negatively associated with loneliness.

PA is negatively associated with loneliness.

NA is positively associated with loneliness.

Mindfulness has a significant indirect effect on loneliness via PANA.

Methods

Data and sample

The data for the study came from a 2022 survey that used convenience sampling in the city of Chengdu, China. Based on statistics obtained from the city government, five communities with high proportions of retired older adults were selected for study recruitment. The inclusion criteria of the sampling process contain individuals who were 1) resided in the five communities selected for this research, 2) aged 50 and above, and 3) retired from the job at the time of the survey. We excluded older adults who were working at the time of the survey. Each community had around 250 retirees. With support from local social workers and street-level committees, we distributed the survey to retired older adults at local senior centers. 1,167 questionnaires were distributed, and 1,085 of them were returned. About 67 questionnaires with missing data in key variables were removed from the analysis, resulting 1,018 valid cases. We further limited the sample to individuals aged 60 and above per the age definition of the elderly in China. The final sample size for this study was 748. Data collection took place from April 27 to June 27, 2022. An informed consent process was implemented prior to the survey, individuals were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could choose to stop the survey at any time. Participants were compensated with 3 RMB (0.5 USD). The ethical approval was obtained from the research review committee at the Research Institute of Social Development in the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics in China. The average age of the sample was 69.7 (S.D.=7.7), and 44.9% of the sample were female. About 25.9% of the sample had below high school education, while 32.8% of them had a high school education. About one-fifth had vocational degrees (21.0%) and another one-fifth had college degrees (20.3%). A majority of the sample was married (85.3%), while a smaller portion were divorced (4.4%). About one-tenth (10.3%) were widowed. These descriptive statistics were comparable to the general retired and older adult population in Chengdu, though our sample had more advantaged socioeconomic characteristics than overall older adults. For example, in Chengdu, 15.6% of older adults in Chengdu have college degrees, compared to the 20.3% in our sample (Chengdu Municipal Health Commission, Citation2022; Sichuan Provincial Bureau of Statistics, Citation2021).

Measures

Loneliness

The outcome variable, loneliness, was measured by the 8-item of UCLA loneliness scale (ULS-8; Hays & DiMatteo, Citation1987). The psychometric soundness, reliability, and validity of the ULS-8 have been verified in various samples in different languages and countries (Doğan et al., Citation2011; Huang et al., Citation2019; Liu et al., Citation2022; Papadopoulos et al., Citation2022). Examples of the items include ‘I lack companionship’ and ‘There is no one I can turn to’. Responses to items in ULS- 8 range from 1 (never) to 4 (always). We reversed positive items so that higher scores indicated greater loneliness. The total of ULS-8 score ranged from 8 to 32. The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.79 in this study.

PANA

PANA were assessed by the 10-item short-form version of the International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (I-PANAS-SF; Thompson, Citation2007), which has demonstrated cross-sample stability, internal reliability, and convergent and criterion-related validity (Liu et al., Citation2020; Jovanovic et al., Citation2022; Thompson, Citation2007). The I-PANAS-SF asks respondents to report on the frequency at which they felt various the emotions (e.g. inspired, determined, hostile, and upset) in the past two weeks. Possible responses range from 1, ‘never’, to 5, ‘always’. We averaged the scores of the items that correspond to PA and to NA. Possible PA and NA scores ranged from 1 to 5. In this study, both PA and NA scales had Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.85 in this study.

Mindfulness

We measured mindfulness using the 20-item short-form version of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Meng et al., Citation2019). The scale was modified from the original 39-item scale developed by Baer et al. (Citation2006), that designed to measure trait-like mindfulness, and has shown high internal consistency and validity in a Chinese sample (Meng et al., Citation2019). Examples of the items include ‘It seems I am running on automatic without much awareness of what I’m doing’ and ‘Usually when I have distressing thoughts or images, I step back and am aware of the thought or image without getting taken over by it’. All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Negatively worded items were reverse coded so that higher scores indicated higher levels of mindfulness. We calculated the mindfulness score by averaging item scores. Possible final scores ranged from 1 to 5. In this study, the FFMQ had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92.

Analytical approach

Descriptive analysis of key variables was first conducted to examine sample characteristics. This was followed by Pearson’s correlation analysis to investigate correlations among the variables. Path analysis was then conducted to simultaneously examine the direct and indirect effects of mindfulness on loneliness through the hypothesized mediators, PA and NA. We also conducted regression analyses with extensive covariates, including personal characteristics. The results from the regression analyses are similar to those reported here. Results of regression analyses are not provided within this study but can be provided upon request. All analyses were conducted using STATA statistical software, version 16.0.

Results

Although the measurement scales used in this study were all from published scales that show verified reliability and validity in literature, it is not clear the extent of the reliability and validity of these scales for retired older adults in this study. We conducted confirmatory factor analysis for all scales (mindfulness, PA, NA, and loneliness). The results show that all scales have at least 0.79 reliability coefficients, and all items in the scales have at least .50 factor loadings, except one item on PA (.23). However, removing this item from PA scale did not change the path analysis results reported in this paper, results available upon request.

presents the descriptive statistics and correlations of key variables. The sample had an average mindfulness score of 3.1. The mean scores for PA and NA were 2.6 and 1.8, respectively. Overall, the sample reported an average loneliness score of 15.7, with a range of 8 to 30. The descriptive statistics suggest that, on average, the sample had relatively high mindfulness and PA, experienced below average NA, and reported moderate loneliness.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations of key variables.

Findings of correlation analysis were consistent with our hypotheses. Mindfulness was positively correlated with PA (r = 0.37, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated to NA (r=-0.21, p < 0.001). Mindfulness was also negatively correlated with loneliness (r=-0.33, p < 0.001). PA was negatively correlated with loneliness (r=-0.10, p < 0.01), while NA was positively correlated with loneliness (r = 0.45, p < 0.001).

The standardized estimates of the path analysis are listed in . Mindfulness had a positive effect on PA (β = 0.37, p < 0.001) and a negative effect on NA (β=-0.21, p < 0.001). These results confirm Hypotheses 1 and 2. Consistent with Hypothesis 3, mindfulness also had a direct and negative effect on loneliness (β=-0.13, p < 0.001). PA was negatively associated with loneliness (β=-0.25, p < 0.001), while NA was positively associated with loneliness (β = 0.52, p < 0.001). These findings support Hypotheses 4 and 5.

The indirect and total effects of mindfulness on loneliness are presented in . Mindfulness had a total effect of −0.33 on loneliness (p < 0.001). The indirect effect of mindfulness on loneliness through PANA was −0.20 (p < 0.001). The proportion of the effect of mindfulness on loneliness mediated by PA and NA was 0.61 (-0.20/-0.33). In other words, PA and NA mediated over half of mindfulness’s effect on loneliness. The above findings are consistent with Hypotheses 6, suggesting that PANA mediated the association between mindfulness and loneliness.

Table 2. Decomposition of the effects of mindfulness on loneliness.

Discussion

The retired older adults in this study, on average, reported moderate loneliness. The average score of loneliness in this study, 15.7, was lower than retirees in Nigeria (20.3; Igbokwe et al., Citation2020), but higher than senior citizens in Philippines (7.2; Carandang et al., Citation2020), rural (11.1; Lu et al., Citation2020) and migrant elderly in China, (12.8; Liu et al., Citation2022), and community older adults in Singapore (14.4; Li et al., Citation2015). Further, prevalence of loneliness—defined by respondents reporting that they felt the following ‘sometimes’ or ‘often’: feelings of lacking companionship; feeling left out of life; and feeling isolated from others (Dong & Chen, Citation2017; Simon et al., Citation2014)—was very high in this study (43%). These findings suggest that, though the sample did not have high level of loneliness, a lot of them experienced many incidences of loneliness in daily life. Given our data were solely from one city in China, more research is needed to investigate the prevalence and extent of loneliness among retired older adults in China, along with how these are related to their well-being.

The results of path analysis showed that mindfulness, PA, and NA all have direct effects on loneliness. In particularly, NA showed a strong positive effect on loneliness, while PA had modest negative effects on loneliness. The results suggest that NA matters more than PA on determining the extent of loneliness in Chinese retired older adults. This might be because NA reduces cognitive functioning and thought-action repertoire of Chinese older adults substantially and prevents them from obtaining the physical, psychological, and social resources they need for reducing loneliness and other health risks (Davidson et al., Citation2022; Wilkes et al., Citation2013). In contrast, consistent with the broaden-and-build theory (Bradley et al., Citation2011), PA improves thought-action repertoire and facilitate social connection of older adults that help them acquire the resources they need for reducing loneliness (Davidson et al., Citation2022; Margrett et al., Citation2011). The magnitude of the effect was modest compared to NA in this study though.

Mindfulness showed modest effects on PA and NA, and its indirect effect on loneliness via PANA was modest as well. The findings are in line with previous studies on mindfulness, PANA, and loneliness and suggest that mindfulness can improve emotional adaption by promoting positive affect and reducing negative affect, which leads to lower stress and loneliness (Mandal et al., Citation2012; Medvedev et al., Citation2021; Perez-Blasco et al., Citation2016; Tumminia et al., Citation2020). Mindfulness enables individuals actively engages in purposeful awareness and maintain non-judgmental reactions to their observations, especially negative events, mindfulness, thus, is able to promote PA and reduce NA and loneliness (Baer et al., Citation2006; Davidson et al., Citation2022; Kabat-Zinn, Citation1990). As most of the previous studies in this area targeted on young adult population, the findings of this study extend the effects of mindfulness on PANA and loneliness to older adults, who face challenges unique to their particular stage of the life course. Within the context in China, which sets an earlier retirement age compared to other countries (Wang et al., Citation2023; Zhang et al., Citation2018), the findings provide further support for the mindfulness framework and the broaden-and-build theory among younger retired adults aged 60 and above in China. In results not shown (available upon request), we conducted the analysis on the whole sample of retired adults aged 50 and above, and the results were similar those in the present sample. The findings contribute to this line of research by adding empirical evidence that mindfulness can be regarded as a valuable resource for middle-aged and older-adult retirees, helping them effectively transition into retirement by increasing their PA and reducing NA and loneliness, key indicators of positive life outcomes (Davidson et al., Citation2022; Roberts & Workman, Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2011).

The findings of this study have practical implications. First, as more than half of the effect of mindfulness on loneliness was mediated by PA and NA, the findings suggest that interventions and services that are designed to increase mindfulness have the potential to help retired older adults improve PA and reduce NA, which consequently can reduce their loneliness. Indeed, there is a plethora of evidence that supporting mindfulness’s effectiveness at improving positive emotions and reducing negative affect, in turn reducing stress and loneliness, but these studies were largely based on data collected from young adults (Garland et al., Citation2015; Mandal et al., Citation2012; Perez-Blasco et al., Citation2016; Tumminia et al., Citation2020). This is indicative of an urgent need to apply mindfulness interventions and services in practice with older adults, thereby improving their mental well-being and reducing their loneliness (Creswell et al., Citation2012; Lee et al., Citation2022; Lindayani et al., Citation2020; Moradizadeh, Citation2019).

Second, given the strong effects of PANA on loneliness, other interventions and services that are successful at reducing NA and increasing PA should be considered. For example, studies have shown that interventions which rely on positive psychology and gratitude can reduce negative emotions and depressive symptoms, improve eudemonic well-being and life satisfaction, and promote positive changes (Dickens, Citation2017; Ho et al., Citation2014; Killen & Macaskill, Citation2015). In addition, there is evidence that interventions for older adults that emphasize forgiveness can significantly reduce negative emotions and affect, as well as improve positive states (Allemand et al., Citation2013; López et al., Citation2021). Consequently, the forgiveness intervention also shows promise in reducing loneliness among retired older adults.

This study has several limitations. First, the study used a cross-sectional design, preventing our ability to infer any causal relations among mindfulness, PANA, and loneliness. However, mindfulness was assessed by trait-like mindfulness measure in this study (Baer et al. Citation2006; Meng et al., Citation2019), which reduced the possibility of reverse causality between mindfulness and affect (Brown & Ryan, Citation2003). This is also consistent with recent literature that argue mindfulness, especially measured in trait-like assessment, influences positive and negative affect and emotion (Carleton et al., Citation2018; Ding et al., Citation2021; Finkelstein-Fox et al., Citation2019; Medvedev et al., Citation2021). Still, Future studies may apply a longitudinal design to account for temporal sequencing and better understand the causal relations among these variables. Second, the survey was based on self-reports of retired older adults in Chengdu, China. Though self-reporting is a common method for collecting data, it might be associated with self-reporting biases that can affect the estimates of the results. For instance, while our survey was anonymous, participants could have underreported NA and overreported PA. Third, the bivariate correlation value between PA and loneliness was low (r=-0.10, p < 0.01), however, PA shows modest effect on reducing loneliness (β=-0.25, p < 0.001) when the analytical model controlled for mindfulness and NA in the path analysis. This suggest the low correlation value between PA and loneliness may be due to PA was picking up some of NA’s effect on loneliness in bivariate correlation as PA and NA was positively correlated (r = 0.38, p < 0.001) and that NA and loneliness was negatively correlated (r=-0.45, p < 0.01). Still, further research on PA, NA, and loneliness among retired older adults is warranted. Finally, the data collection occurred in one city, Chengdu, so our findings may not be generalizable to the larger population of retired older adults in China. A future study could expand upon our findings by examining how geographic differences in China (e.g. rural versus urban) might affect the mediational pathway between mindfulness and loneliness through PA and NA.

Conclusion

This study used data from 748 retired older adults in Chengdu, China, to investigate the extent to which mindfulness influences loneliness and whether this relation is mediated by PA and NA. The findings of this study support the mindfulness framework and the broaden-and-build theory and indicate that mindfulness could be used as a resource to improve PA and reduce NA, thereby reducing loneliness in retired older adults in China. Loneliness is a critical target outcome because of its vital effects on health and well-being, particularly in retired older adults. The findings of this study call for the delivery of mindfulness interventions and services for retired older adults in China.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allemand, M., Steiner, M., & Hill, P. L. (2013). Effects of a forgiveness intervention for older adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(2), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031839

- Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504

- Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph077

- Bradley, B., DeFife, J. A., Guarnaccia, C., Phifer, J., Fani, N., Ressler, K. J., & Westen, D. (2011). Emotion dysregulation and negative affect: Association with psychiatric symptoms. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(5), 685–691. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.10m06409blu

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

- Cacioppo, J. T., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2006). Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging, 21(1), 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140

- Carandang, R. R., Shibanuma, A., Asis, E., Chavez, D. C., Tuliao, M. T., & Jimba, M. (2020). “Are Filipinos Aging Well?”: Determinants of subjective well-being among senior citizens of the community-based ENGAGE study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207636

- Carleton, E. L., Barling, J., & Trivisonno, M. (2018). Leaders’ trait mindfulness and transformational leadership: The mediating roles of leaders’ positive affect and leadership self-efficacy. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences du Comportement, 50(3), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000103

- Chen, Y., Zhang, F., Wang, Y., & Zheng, J. (2020). Work-family conflict, emotional responses, workplace deviance, and well-being among construction professionals: A sequential mediation model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6883. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186883

- Chengdu Human Resources and Social Security Bureau. (2021). Statistical bulletin of Chengdu human resources and social security development in 2020. Chengdu Human Resources and Social Security Bureau, Chengdu, China. Retrieved July 26, 2022, from http://cdhrss.chengdu.gov.cn/cdrsj/c109733/2021-09/30/content_5a4f312638c2440ba9aff11b65313759.shtml

- Chengdu Municipal Health Commission. (2022). Elderly population information and aged career development status report in Chengdu in 2021

- Cheung, S., Xie, X., Huang, C.-C., & Li, X. (2022). Job demands and resources and employee well-being among social workers in china: The mediating effects of affect. The British Journal of Social Work, 52(7), 4204–4222. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcac043

- Creswell, J. D., Irwin, M. R., Burklund, L. J., Lieberman, M. D., Arevalo, J. M. G., Ma, J., Breen, E. C., & Cole, S. W. (2012). Mindfulness-based stress reduction training reduces loneliness and pro-inflammatory gene expression in older adults: A small randomized controlled trial. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 26(7), 1095–1101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.006

- Davidson, E. J., Taylor, C. T., Ayers, C. R., Quach, N. E., Tu, X. M., & Lee, E. E. (2022). The relationship between loneliness and positive affect in older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry : Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(6), 678–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2021.11.002

- Dickens, L. R. (2017). Using gratitude to promote positive change: A series of meta-analyses investigating the effectiveness of gratitude interventions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 39(4), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2017.1323638

- Diener, E., & Emmons, R. A. (1984). The independence of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(5), 1105–1117. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.47.5.1105

- Ding, X., Zhao, T., Li, X., Yang, Z., & Tang, Y. Y. (2021). Exploring the relationship between trait mindfulness and interpersonal sensitivity for Chinese college students: The mediating role of negative emotions and moderating role of effectiveness/authenticity. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 624340. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.624340

- Doğan, T., Çötok, N. A., & Tekin, E. G. (2011). Reliability and validity of the Turkish Version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-8) among university students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 2058–2062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.053

- Domènech-Abella, J., Lara, E., Rubio-Valera, M., Olaya, B., Moneta, M. V., Rico-Uribe, L. A., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Mundó, J., & Haro, J. M. (2017). Loneliness and depression in the elderly: The role of social network. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(4), 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1339-3

- Dong, X., Simon, M. A., Gorbien, M., Percak, J., & Golden, R. (2007). Loneliness in older Chinese adults: A risk factor for elder mistreatment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55(11), 1831–1835. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01429.x

- Dong, X., & Chen, R. (2017). Gender differences in the experience of loneliness in US Chinese older adults. Journal of Women & Aging, 29(2), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2015.1080534

- Feng, Z., Glinskaya, E., Chen, H., Gong, S., Qiu, Y., Xu, J., & Yip, W. (2020). Long-term care system for older adults in China: Policy landscape, challenges, and future prospects. Lancet (London, England), 396(10259), 1362–1372. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32136-X

- Finkelstein-Fox, L., Park, C. L., & Riley, K. E. (2019). Mindfulness’ effects on stress, coping, and mood: A daily diary goodness-of-fit study. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 19(6), 1002–1013. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000495

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Fowler, R. D. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. The American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

- Garland, E. L., Fredrickson, B., Kring, A. M., Johnson, D. P., Meyer, P. S., & Penn, D. L. (2010). Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 849–864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.002

- Garland, E. L., Geschwind, N., Peeters, F., & Wichers, M. (2015). Mindfulness training promotes upward spirals of positive affect and cognition: Multilevel and autoregressive latent trajectory modeling analyses. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(15), eCollection. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00015

- Gawrysiak, M. J., Grassetti, S. N., Greeson, J. M., Shorey, R. C., Pohlig, R., & Baime, M. J. (2018). The many facets of mindfulness and the prediction of change following mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(4), 523–535. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22521

- Ghadampour, E., Moradizadeh, S., & Shahkarami, M. (2018). The Effectiveness of Mindfulness Training on Increasing Happiness and Improving Quality of Life in Elderly. Aging Psychology, 4(1), 27–38.

- Gloria, C. T., & Steinhardt, M. A. (2016). Relationships among positive emotions, coping, resilience and mental health: Positive emotions, resilience and health. Stress and Health : journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 32(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2589

- Hawkley, L. C., Thisted, R. A., Masi, C. M., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness predicts increased blood pressure: 5-year cross-lagged analyses in middle-aged and older adults. Psychology and Aging, 25(1), 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017805

- Hays, R. D., & DiMatteo, M. R. (1987). A short-form measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 51(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5101_6

- He, D., Shi, M., & Yi, F. (2014). Mediating effects of affect and loneliness on the relationship between core self-evaluation and life satisfaction among two groups of Chinese adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 119(2), 747–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0508-3

- Ho, H. C., Yeung, D. Y., & Kwok, S. Y. (2014). Development and evaluation of the positive psychology intervention for older adults. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(3), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.888577

- Huang, L. J., Du, W. T., Liu, Y. C., Guo, L. N., Zhang, J. J., Qin, M. M., & Liu, K. (2019). Loneliness, stress, and depressive symptoms among the Chinese rural empty nest elderly: A moderated mediation analysis. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40(1), 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2018.1437856

- Hülsheger, U. R., Alberts, H. J., Feinholdt, A., & Lang, J. W. (2013). Benefits of mindfulness at work: The role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 310–325. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031313

- Igbokwe, C. C., Ejeh, V. J., Agbaje, O. S., Umoke, P. I. C., Iweama, C. N., & Ozoemena, E. L. (2020). Prevalence of loneliness and association with depressive and anxiety symptoms among retirees in Northcentral Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01561-4

- Jonas, B. S., & Lando, J. F. (2000). Negative affect as a prospective risk factor for hypertension. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62(2), 188–196. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200003000-00006

- Jovanovic, V., Joshanloo, M., Martín-Carbonell, M., Caudek, C., Espejo, B., Checa, I., Krasko, J., Kyriazos, T., Piotrowski, J., Rice, S. P. M., Junça Silva, A., Singh, K., Sumi, K., Tong, K. K., Yıldırım, M., & Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M. (2022). Measurement invariance of the scale of positive and negative experience across 13 countries. Assessment, 29(7), 1507–1521. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911211021494

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your mind and body to face stress, pain, and illness. Delacorte.

- Killen, A., & Macaskill, A. (2015). Using a gratitude intervention to enhance well-being in older adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(4), 947–964. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9542-3

- Kim, J. E., & Moen, P. (2002). Retirement transitions, gender, and psychological well-being: A life-course, ecological model. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57(3), P212–P222. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.3.P212

- Lee, E. K. P., Wong, B., Chan, P. H. S., Zhang, D. D., Sun, W., Chan, D. C. C., … Wong, S. Y. S. (2022). Effectiveness of a mindfulness intervention for older adults to improve emotional well-being and cognitive function in a Chinese population: A randomized waitlist-controlled trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 37(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5616

- Lee, K., Martin, P., & Poon, L. W. (2017). Predictors of caregiving burden: Impact of subjective health, negative affect, and loneliness of octogenarians and centenarians. Aging & Mental Health, 21(11), 1214–1221. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1206512

- Li, J., Theng, Y. L., & Foo, S. (2015). Depression and psychosocial risk factors among community-dwelling older adults in Singapore. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 30(4), 409–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-015-9272-y

- Li, W., Ye, X., Zhu, D., & He, P. (2021). The longitudinal association between retirement and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 190(10), 2220–2230. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab125

- Lindayani, L., Hendra, A., Juniarni, L., & Nurdina, G. (2020). Effectiveness of mindfulness based stress reduction on depression in elderly: A systematic review. Journal of Nursing Practice, 4(1), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.30994/jnp.v4i1.101

- Lindsay, E. K., Young, S., Brown, K. W., Smyth, J. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2019). Mindfulness training reduces loneliness and increases social contact in a randomized controlled trial. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(9), 3488–3493. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1813588116

- Liu, G., Li, S., & Kong, F. (2022). Association between social support, smartphone usage and loneliness among the migrant elderly following children in Jinan, China: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 12(5), e060510. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060510

- Liu, J.-D., You, R.-H., Liu, H., & Chung, P.-K. (2020). Chinese version of the international positive and negative affect schedule short form: Factor structure and measurement invariance. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 18(1), 1–8. Article 285. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01526-6

- López, J., Serrano, M. I., Giménez, I., & Noriega, C. (2021). Forgiveness interventions for older adults: A review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(9), 1866. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10091866

- Lu, L., Xu, L., Luan, X., Sun, L., Li, J., Qin, W., Zhang, J., Jing, X., Wang, Y., Xia, Y., Li, Y., & Jiao, A. (2020). Gender difference in suicidal ideation and related factors among rural elderly: A cross-sectional study in Shandong, China. Annals of General Psychiatry, 19(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-019-0256-0

- Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803–855. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803

- Margrett, J. A., Daugherty, K., Martin, P., MacDonald, M., Davey, A., Woodard, J. L., Miller, L. S., Siegler, I. C., & Poon, L. W. (2011). Affect and loneliness among centenarians and the oldest old: The role of individual and social resources. Aging & Mental Health, 15(3), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2010.519327

- Mandal, S. P., Arya, Y. K., & Pandey, R. (2012). Mental health and mindfulness: Mediational role of positive and negative affect. SIS Journal of Projective Psychology and Mental Health, 19(2), 150–159.

- Medvedev, O. N., Cervin, M., Barcaccia, B., Siegert, R. J., Roemer, A., & Krägeloh, C. U. (2021). Network analysis of mindfulness facets, affect, compassion, and distress. Mindfulness, 12(4), 911–922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01555-8

- Meng, Y., Mao, K., & Li, C. (2019). Validation of a short-form five facet mindfulness questionnaire instrument in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 3031. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03031

- Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. (2022). Statistical bulletin on the development of human resources and social security in 2021. Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. Beijing, China. Retrieved July 23, 2022, from http://www.mohrss.gov.cn/SYrlzyhshbzb/zwgk/szrs/tjgb/202206/t20220607_452104.html

- Moradizadeh, S. (2019). The Study of effectiveness of training of mind consciousness on reduction of the elderly’s feeling of loneliness and death anxiety in Sedigh Center of Khoramabad City. Razi Journal of Medical Sciences, 26(4), 44–53.

- Neto, F. (2014). Psychometric analysis of the short-form UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-6) in older adults. European Journal of Ageing, 11(4), 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-014-0312-1

- O’Connor, M., Piet, J., & Hougaard, E. (2014). The effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on depressive symptoms in elderly bereaved people with loss-related distress: A controlled pilot study. Mindfulness, 5(4), 400–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0194-x

- Pandya, S. P. (2021). Meditation program mitigates loneliness and promotes wellbeing, life satisfaction and contentment among retired older adults: A two-year follow-up study in four South Asian cities. Aging & Mental Health, 25(2), 286–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1691143

- Papadopoulos, C., Castro, N., Nigath, A., Davidson, R., Faulkes, N., Menicatti, R., Khaliq, A. A., Recchiuto, C., Battistuzzi, L., Randhawa, G., Merton, L., Kanoria, S., Chong, N.-Y., Kamide, H., Hewson, D., & Sgorbissa, A. (2022). The CARESSES randomised controlled trial: Exploring the health-related impact of culturally competent artificial intelligence embedded into socially assistive robots and tested in older adult care homes. International Journal of Social Robotics, 14(1), 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-021-00781-x

- Peplau, L., & Perlman, D. (1982). Perspectives on loneliness. In L. Peplau & D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy (pp. 1–20). Wiley.

- Perez-Blasco, J., Sales, A., Meléndez, J. C., & Mayordomo, T. (2016). The effects of mindfulness and self-compassion on improving the capacity to adapt to stress situations in elderly people living in the community. Clinical Gerontologist, 39(2), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2015.1120253

- Population Reference. Bureau. (2019). Fact sheet: Aging in the United States [Fact sheet]. https://www.prb.org/resources/fact-sheet-aging-in-the-united-states/

- Roberts, G. W., & Workman, R. (2019). Positive ageing–transitioning into retirement and beyond.: An appreciative coaching approach for health and social care professionals. novum pro Verlag.

- Sichuan Provincial Bureau of Statistics. (2021). Bulletin of the Seventh National Census of Sichuan Province (No. 4).

- Simon, M. A., Chang, E. S., Zhang, M., Ruan, J., & Dong, X. (2014). The prevalence of loneliness among US Chinese older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 26(7), 1172–1188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264314533722

- Snippe, E., Nyklíček, I., Schroevers, M. J., & Bos, E. H. (2015). The temporal order of change in daily mindfulness and affect during mindfulness-based stress reduction. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(2), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000057

- Srivastava, S., Ramanathan, M., Dhillon, P., Maurya, C., & Singh, S. K. (2021). Gender differentials in prevalence of loneliness among older adults in India: An analysis from who study on global Ageing and adult health. Ageing International, 46(4), 395–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-020-09394-7

- Stenling, A., Henning, G., Bjälkebring, P., Tafvelin, S., Kivi, M., Johansson, B., & Lindwall, M. (2021). Basic psychological need satisfaction across the retirement transition: Changes and longitudinal associations with depressive symptoms. Motivation and Emotion, 45(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-020-09854-2

- Sunwoo, L. (2020). Loneliness among older adults in the Czech Republic: A socio-demographic, health, and psychosocial profile. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 90, 104068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2020.104068

- Teneva, N., & Lemay, E. P. (2020). Projecting loneliness into the past and future: Implications for self-esteem and affect. Motivation and Emotion, 44(5), 772–784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-020-09842-6

- Thompson, E. R. (2007). Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38(2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022106297301

- Tumminia, M. J., Colaianne, B. A., Roeser, R. W., & Galla, B. M. (2020). How is mindfulness linked to negative and positive affect? Rumination as an explanatory process in a prospective longitudinal study of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(10), 2136–2148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01238-6

- van Roekel, E., Ha, T., Verhagen, M., Kuntsche, E., Scholte, R. H., & Engels, R. C. (2015). Social stress in early adolescents’ daily lives: Associations with affect and loneliness. Journal of Adolescence, 45, 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.10.012

- Wang, M., Henkens, K., & van Solinge, H. (2011). Retirement adjustment: A review of theoretical and empirical advancements. The American Psychologist, 66(3), 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022414

- Wang, Z., Chen, Y., & Chen, Y. (2023). The effect of retirement on the health of elderly people: Evidence from China. Ageing & Society, 43(6), 1284–1309. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X21001094

- Weiss, H. M. (2002). Deconstructing job satisfaction: Separating evaluations, beliefs, and affective experiences. Human Resource Management Review, 12(2), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(02)00045-1

- Wilkes, C. M., Wilson, H. W., Woodard, J. L., & Calamari, J. E. (2013). Do negative affect characteristics and subjective memory concerns increase risk for late life anxiety? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(6), 608–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.03.008

- Wu, Z. Q., Sun, L., Sun, Y. H., Zhang, X. J., Tao, F. B., & Cui, G. H. (2010). Correlation between loneliness and social relationship among empty nest elderly in Anhui rural area, China. Aging & Mental Health, 14(1), 108–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860903228796

- Yang, K., & Victor, C. R. (2008). The prevalence of and risk factors for loneliness among older people in China. Ageing and Society, 28(3), 305–327. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X07006848

- Zacher, H., & Rudolph, C. W. (2021). Individual differences and changes in subjective wellbeing during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Psychologist, 76(1), 50–62. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000702

- Zhang, Y., & Han, B. (2016). Positive affect and mortality risk in older adults: A meta-analysis. PsyCh Journal, 5(2), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.129

- Zhang, Y., Salm, M., & van Soest, A. (2018). The effect of retirement on healthcare utilization: Evidence from China. Journal of Health Economics, 62, 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2018.09.009

- Zhang, Z., & Zhang, J. (2015). Social participation and subjective well-being among retirees in China. Social Indicators Research, 123(1), 143–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0728-1

- Zhou, Z., Mao, F., Zhang, W., Towne, S. D., Wang, P., & Fang, Y. (2019). The association between loneliness and cognitive impairment among older men and women in China: A nationwide longitudinal study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(16), 2877. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16162877