?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objectives

Through a process of ‘creative ageing’, there is increased interest in how active participation in the arts can help promote health and well-being among seniors. However, few studies have quantitatively examined the benefits of a foray into artistic expression, and even fewer employ rigorous identification strategies. Addressing this knowledge gap, we use a series of quantitative techniques (ordinary least squares and quantile regression) to analyze the impact of an arts-based intervention targeting the elderly.

Methods

Recruited from Saint John, New Brunswick (a city of about 125,000 people in Eastern Canada), 130 seniors were randomly assigned to the programme, with the remaining 122 serving as the control. This intervention consisted of weekly 2-h art sessions (i.e. drawing, painting, collage, clay-work, performance, sculpting, and mixed media), taking place from January 2020 until April 2021.

Results

Relative to the control group, the intervention tended to reduce participant loneliness and depression, and improve their mental health. Outcomes were more evident toward the latter part of the programme, were increasing in attendance, and most efficacious among those with initially low levels of well-being.

Conclusion

These findings imply that creative ageing promotes healthy ageing, which is especially noteworthy given COVID-19 likely attenuated our results.

Keywords:

Introduction

Although father time remains undefeated, people strive to improve the human condition in their pursuit, as Groucho Marx puts it, ‘to live forever or die trying’. Likewise, concerns over an ageing population in Canada have been discussed at length by academics and policy-makers, typically focusing on healthy ageing and the fiscal sustainability of the public health care system (Wilson et al., Citation2012). These matters are particularly distressing to a province like New Brunswick which, according to recent Statistics Canada estimates, has the second highest percentage of seniors (22%) in the country (see: CANSIM Table 17-10-0005-01). Further, this pandemic has illustrated the especially alarming levels of loneliness and isolation of our elderly population, which certainly motivates endeavours to improve upon such troubling conditions (Kasar & Karaman, Citation2021). Therefore, innovative programmes designed to improve the health and well-being of senior populations are both socially and morally beneficial.

Among possible interventions, there has been increasing interest in how exposure to the arts can improve the health and well-being of the elderly. Chapwell (Citation2014) directly advocates for rigorous scientific study on this matter; the alternative option of reliance on antidepressants to combat increasing levels of loneliness and social isolation, he argues, is deeply unattractive. However, to date, only a limited number of studies have empirically examined the health benefits resulting from a foray into artistic expression using rigorous quantitative methods. This concern is directly referenced by Hanna et al. (Citation2015) who note that ‘criticisms about the quality of this research and questions about its real place in scientific investigation have hampered the growth of the field’ (p. 277). Thus, this work seeks to extend the current literature on ‘creative ageing’, which we define as ‘active participation in the arts’, by using a set of regression methods (which control for a host of potentially confounding factors) to explore the impacts of an arts-based programme targeting seniors.

The primary hypothesis for this study is motivated by Gene Cohen’s findings in his 2006 landmark paper, ‘The Creativity and Aging Study’—i.e. relative to the control group, we posited that this arts-based endeavour would improve both the well-being and physical health of programme participants. While most geriatric studies empirically support Cohen’s seminal work by using data collected within the past 10–15 years (see: section Background and motivation), historical analyses also suggest that artists, born between 1700 and 1899, had life expectancies similar to the ‘elite’ class (Mirzada et al., Citation2014). From a health perspective, a recent study finds that creative endeavours use processes in the brain that are not necessarily impaired due to ageing, and therefore serve as an opportunity for well-being improvement among the elderly (Ehresman, Citation2014). The latter result is also supported in a psychological study by Palmiero et al. (Citation2016) who suggest that creativity is positively associated with cognitive reserve among seniors.

Recruited from Saint John, New Brunswick, a city of about 125,000 people in eastern Canada, 252 eligible participants, age 65 and over, volunteered for an arts-themed randomized controlled trial running from January 2020 until December 2020. The control group was comprised of 122 seniors, with the remaining 130 taking part in an intervention that consisted of weekly 2-h art sessions. Topics included: drawing, painting, collage, clay-work, performance, sculpting, and mixed media. Initially planned as a 12-month programme, the project was extended to April 2021 due to interruptions as a result of COVID-19. However, despite these stoppages, the project was run in its entirety and under strict adherence to the province of New Brunswick’s Public Health requirements for in-person gatherings. Over the course of this study, participants in the intervention and control groups were administered a set of well-being and physical health questionnaires at five time-points (December 2019, July/August 2020, November 2020, March 2021, May 2021); socioeconomic and demographic data were also collected at baseline.

Using ordinary least squares, regression results suggest that this intervention had a positive impact on well-being; however, the effects on physical health are not as apparent. The programme produced statistically significant findings in terms of reducing loneliness and depression, along with improving mental health and emotional well-being. Additionally, the arts-based intervention tended to increase the participant’s level of vitality and the quality of their social interactions. Although we do not observe improvements in self-reported health, bodily pain, or number of medications taken, there are predicted increases in both basic and intermediate-level physical functioning, implying that programme participants were more likely to experience increased capability in carrying out daily activities, such as climbing stairs and buying groceries. Furthermore, our findings are robust to the inclusion of socioeconomic and demographic factors, along with controlling for whether or not the respondent had recently joined another organization. Known as the John Henry Effect, if the control group were more likely to have sought alternative programming, and had we not controlled for this in the regression, then there may have been an attenuation bias concerning the treatment effect (i.e. the control group may have experienced improved health and well-being as a result of participating in a different endeavour).

The largest treatment effects emerged at the end of the study, suggesting that health and well-being improvements tended to become increasingly apparent over the course of the intervention. These effect sizes are also increasing in attendance. While results tend to be small and statistically insignificant when observing a treatment group that includes those who failed to participate in the bulk of the classes, there is a distinct shift to a set of consistently impactful results when observing those with strong attendance. Lastly, quantile regression results suggest that the programme was most efficacious for those with low initial levels of well-being. Specifically, those in the lowest well-being quartiles are predicted to have incurred well-being improvements that were about twice as large as those experienced by the average programme participant. Consequently, this provides further evidence that our results are not merely spurious, and are indeed capturing the benefits of this endeavour.

The rest of the paper is laid out as follows. Section Background and motivation provides a brief literature review that motivates our study, while section Methods outlines the intervention, data collection, and methods. Results are presented in section Results, and section Discussion and conclusion concludes.

Background and motivation

Cohen (Citation2009) argues that arts-based interventions improve a participant’s sense of control, expand their social support network, enhance brain activity, and tap into an increasing preference for arts later in life. Further, both Flood and Phillips (Citation2007) and Noice et al. (Citation2014) note that past evidence suggests interventions stressing creativity through artistic endeavour, tend to improve the health of seniors. In a systematic review, Dunphy et al. (Citation2018) find that arts-based interventions are associated with reduced depression symptoms. Regarding specific artistic endeavours, Bernard and Rickett (Citation2017) identify past literature on the impact of theatre involvement among seniors, observing a consistent positive influence on their health and well-being. Moreover, in a meta-analysis, Liu et al. (Citation2021) suggest that while dance interventions improve the cognitive capabilities of the elderly, they do not impact the mental health of participants.

Qualitative evidence suggests that arts-based programming has a positive association with cognitive ability (Alders & Levine-Madori, Citation2010; Alders-Pike, Citation2013; Bugos, Citation2014; Lawton & La Porte, Citation2013), memory (Wakeling & Clark, Citation2015), a sense of identity (Rodrigues et al., Citation2019), being in the present (Sabeti, Citation2015), well-being (Johnson & Sullivan-Marx, Citation2006; Southcott & Li, Citation2018), resilience (McFadden & Basting, Citation2010), and personal improvement (Gutheil & Heyman, Citation2016). Further, Balyasnikova and Gillard (Citation2021) find that creative literacy programmes using arts-based activities for elderly immigrants, not only help in developing English skills but also foster social connections outside of their communities, thus improving upon their self-esteem and well-being. Also by means of qualitative methods, Adams-Price et al. (Citation2018) argue that the relationship between generativity and life satisfaction is, in part, driven by creative pursuit—a finding that corroborates de Medeiros (Citation2009).

Using a pre/post-test design, Johnson et al. (Citation2021) report that seniors participating in a ceramics intervention were more likely to experience greater interest in life; however, no statistical change could be found among those who partook in creative writing. Given a set of similar methods, Noice et al. (Citation2004) suggest that, relative to a control group, those seniors participating in a theatre programme had improved levels of cognition and well-being. Using analysis of variance methods, Ueno et al. (Citation2015) find that creativity is associated with increased brain activity and Fields et al. (Citation2021) suggest that a robot-delivered Shakespearean production promoted reduced levels of depression and loneliness among those involved. Finally, Poulos et al. (Citation2019) observe that relative to baseline levels, an arts programme consisting of several endeavours for elderly participants, predicted statistically significant mental health improvement.

While the above studies are either qualitative or rely on basic quantitative methods, recent work is beginning to use more sophisticated techniques to examine the causal benefits of creative ageing. By means of a set of regression models, Beauchet et al. (Citation2020) find that, for geriatric inpatients who participated in painting workshops, both medication use at discharge and in-house mortality decreased. Liddle et al. (Citation2012) run a series of logistic regressions and find that elderly women, who began actively engaging in music or painting, were more likely to report higher levels of emotional well-being; conversely, those who stopped were expected to experience a decline. Ho et al. (Citation2019) employ propensity score matching and conclude that both passive and active engagement in the arts enhanced the quality of life and self-reported health of seniors. Using a generalized estimating equations framework, Keisari et al. (Citation2020) note that a theatre-based intervention predicted mental health improvement for older adults, and this positive impact continued to persist 3-months post intervention. Lastly, Yu et al. (Citation2021) employ hierarchical linear modelling methods and find that art therapy is associated with cognitive gains among seniors.

Two of the most unique papers that examine the health impacts of arts engagement are Fancourt and Steptoe (Citation2019) and Wang et al. (Citation2020). The former argue that relative to adults who did not participate in the arts, moderate engagement predicts a 14% reduction in mortality, and frequent engagement predicts a 31% reduction. The latter suggests that artistic activities are associated with reduced distress and increased life satisfaction. These studies are distinctive in that they observe a large number of respondents (6710 and 23,600, respectively), over a relatively long period of time (14 and 5 years, respectively). Additionally, they employ advanced quantitative techniques (Cox proportional hazard models and fixed effects transformations) that extend beyond the commonly used pre/post-test methods and simple linear regression models.

A scoping review performed by Fraser et al. (Citation2015) concludes that most interventions: (i) occurred in the United States, (ii) focused on a specific type of artistic endeavour, and (iii) were qualitative. Therefore, we fill this literature gap based on a randomized controlled trial that causally examines how exposure to several forms of art (drawing, painting, collage, clay-work, performance, sculpting, and mixed media) impacted the health and well-being of a random sample of elderly participants in a Canadian city (Saint John). We explore this relationship by observing a host of standardized outcomes and extend upon the more recent quantitative literature by using regression models that condition on both the mean and various points of the outcome distributions. Furthermore, regressions control for several explanatory variables, allowing for more precise estimation of intervention efficacy.

Methods

Description of intervention

A poster was circulated throughout the city of Saint John to recruit participants for our randomized controlled trial. Senior centres, places of worship, physician offices, and community centres were particularly targeted. Additionally, the poster was circulated on various social media platforms, on the radio, and in local newspapers. As a result of our recruitment campaign, 263 seniors agreed to take part in the study.Footnote1

Those agreeing to participate were administered the Edmonton Frail Scale (Rolfson et al., Citation2006). This index was used to determine inclusion to attenuate the potential decline in participation over the study period due to health concerns. This questionnaire examines the following frailty domains: cognition, general health status, functional independence, social support, medication use, nutrition, mood, continence, and functional performance. Based on this set of domains, a score ranging from 0 to 17, increasing in frailty, can be tabulated. The developers of this survey suggest that a value between 0 and 5 indicates the absence of frailty, and this threshold was used as our inclusion criteria. Consequently, this test excluded 11 individuals (who scored above a value of 5), leaving 252 study participants. Further, as discussed in greater detail below, 130 of these individuals were randomly assigned to the arts-based intervention, with the remaining 122 serving as the control group. Not known to them during the study period, the control group was compensated for their efforts, being given a series of free arts-based classes post-intervention.

Concerning the programme, weekly 2-h sessions were held over a 16-month period and consisted of a mix of drawing, painting (acrylic, one-stroke, and water colour), collage, clay-work, performance (creative movement and theatre), sculpting, and mixed media. We chose to include active participation in both visual and performance art given that most seniors had very little (if any) exposure to the latter form of art. Most participants were familiar with visual arts and had at least minimal experience with it at some point in their life, but very few had explored performance art. Therefore, our objective was to expose participants to a variety of artistic activities, which in some cases, meant challenging them to try something completely new.

Classes were held at four different locations around the city and six local artists were hired to provide instruction.Footnote2 The intention was that each artist, along with a support worker, would deliver one activity for 3 weeks in a single location before moving to the next location. Therefore, within a given 12-week period, participants would experience a series of different art activities facilitated by four of the recruited artists. This process would then resume with another four of the six artists providing their expertise over a similar period of time. Consequently, this intervention was supposed to be a series of four 12-week blocks taking place over a 12-month period (with both the control and treatment groups being surveyed at the end of each block). However, COVID-19 lock-down procedures, beginning in March 2020, required that we extend the programme to run over a 16-month period. Specifically, lock-downs reduced the first block to 9 weeks, delayed the start of the second block, and due to resulting time and logistical constraints, the fourth block also had to be reduced to 9 weeks. Nevertheless, within each block, the treatment group participated in both visual and performance art—i.e. each block was not devoted to a particular activity.Footnote3

The primary reason for this extension was because classes were suspended on March 15th and could not resume until 10th August.Footnote4 However, for the remainder of the study, classes were only cancelled twice due to the province’s ‘Red Phase’, which required that social activities be stopped for short durations. Although only two classes had to be cancelled, we should note that survey data collected in March 2021 occurred shortly after one of these lock-down periods. This is further addressed in section Discussion and conclusion.

Data collection

During the first wave of data collection, which took place before the onset of the intervention (December 2019), respondents were asked a series of demographic and socioeconomic questions (written informed consent was provided by all participants). Regarding their demographic profile, respondents were queried on their: sex, age, marital status, and whether or not they were an immigrant and/or visible minority. The socioeconomic questions included: annual household income and the highest level of education. These data allowed us to compare the control and treatment groups, ensuring that no observable statistical differences were present. Additionally, these questions serve as a set of baseline control variables that provide our models with increased explanatory power.

As presented in , the intervention and control groups did not statistically differ on these baseline observables, thereby ameliorating concerns that differences in the composition of treatment and control groups biased our results. Concerning health and well-being, each group was observed five times over the study period and all participants provided written informed consent during each wave of collection. Aside from the baseline survey, data collection coincided with the end of each block of artistic activities. However, as a result of the March 2020 lock-down, we were unable to survey respondents directly after the first block—i.e. data collection did not begin until late July. For the remainder of the study, the timing of data collection proceeded as planned, occurring at the end of each artistic block (i.e. during the months of November 2020, March 2021, and May 2021). This March-July time lag in data collection is addressed in section Results, based on results.

Table 1. Baseline socioeconomic and demographic descriptive statistics for all recruited participants.

Table 4. Key regression results: discrete time.

Notably, there was attrition, which was amplified by the onset of COVID-19.Footnote5 Nonetheless, by the end of the study, there were 86 individuals still participating in the intervention and 48 remaining in the control group. To ensure that there was no systematic attrition, such that one group became observably different by the end of the study, a comparison of baseline mean characteristics among those who participated in all waves suggests these two groups did not statistically differ (results are available from the lead author upon request). A flowchart of our study is presented in the Appendix.

In addition to demographic and socioeconomic information, respondents were also asked to evaluate their physical health on a 5-point scale ranging from ‘Excellent’ to ‘Poor’, and this question was also asked in each of the four follow-up waves of data collection. Moreover, beginning in the second wave, individuals were asked to report on the number of medications they were currently taking (excluding vitamins). Lastly, in all five waves, respondents were asked to report on whether or not they recently joined another organization and were also administered four well-validated surveys concerning physical health and well-being: the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., Citation1978), the Geriatric Depression Scale (Sheikh & Yesavage, Citation1986), the Functional Status Questionnaire (Jette et al., Citation1986), and the SF-36v2 Health Survey (Ware et al., Citation1993).

The UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., Citation1978) measures a person’s subjective feelings of loneliness and social isolation on a 20-item scale. For each question, a respondent may select ‘I often feel this way’ [3], ‘I sometimes feel this way’ [2], ‘I rarely feel this way’ [1], and ‘I never feel this way’ [0]. Values, indicated in square brackets, are summed to produce a 60-point index, increasing in feelings of loneliness and social isolation, which for our study was rescaled within a 0–100 boundary. Examples of questions include: ‘I am no longer close to anyone’, ‘I have nobody to talk to’, and ‘I feel starved for company’.

The Geriatric Depression Scale (Sheikh & Yesavage, Citation1986) is a 15-question survey concerning feelings the respondent had over the previous week and is increasing in depressive symptoms. The index is based on the summation of yes/no responses to questions, such as ‘are you basically satisfied with life’, ‘do you often feel helpless’, and ‘do you feel pretty worthless the way you are now’. A value of unity is given to a response that indicates depression; zero otherwise. For interpretation purposes, this index was rescaled within the boundaries of a 100-point scale.

The Functional Status Questionnaire (Jette et al., Citation1986) provides an assessment of social engagement based on an inventory of participant activities over the previous month; specific attention is given to the nature, frequency, and duration of these activities. This survey is broken into four sections: (1) physical functioning, (2) mental health, (3) social activity, and (4) quality of interactions. A 100-point scale was derived for each component, based on the summation of values in the square brackets below, and captures increases in that particular function. Questions concerning physical functioning are broken into basic and intermediate levels of activity and are based on a series household-related tasks whereby the respondent was asked to rate their respective difficulties on a 4-point scale: ‘Usually no difficulty’ [4], ‘Some difficulty’ [3], ‘Much difficulty’ [2], and ‘Usually did not do because of health’ [1]. The mental health component consists of five questions concerning one’s level of psychological functioning. For each question, the respondent has six options: ‘None of the time’ [6], ‘A little of the time’ [5], ‘Some of the time’ [4], ‘A good bit of the time’ [3], ‘Most of the time’ [2], and ‘All of the time’ [1]. Notably, square bracket values relate to questions that suggest the presence of psychological distress; values are reverse-coded for questions implying improved mental health. Regarding social activity, three questions were asked and scoring is identical to that of physical functioning. These questions pertain to the degree of difficulty an individual had in visiting with friends/family, participating in social events, and taking care of others. Lastly, the quality of interactions was derived using five questions with scoring that is akin to that of the mental health index. The questions capture feelings of isolation from others, along with their level of companionship with those around them.

The SF-36v2 Health Survey (Ware et al., Citation1993) provides measures of a participant’s health and well-being over the past four weeks. This quality of life questionnaire measures: social functioning (i.e. the extent to which emotional problems impeded social activity), physical functioning (i.e. the extent to which physical health limited typical physical activity), emotional well-being (i.e. the extent to which emotional problems impacted daily activity), physical role (i.e. if physical health reduced the respondent’s level of work, both inside and outside the home), vitality (i.e. the level of energy the respondent has recently felt), general health, bodily pain, and mental health. Each index was derived based on the summation of responses to 2–10 questions, which range from yes/no options to those on a Likert scale. Indices were coded on a 0–100 point scale, increasing in a positive outcome. Given that the mental health component is an exact replica of the mental health questions from the Functional Status Questionnaire, it was dropped from the study.

Given the above questionnaires, we derive a set of eight metrics assessing well-being and six capturing physical health, all of which are on 100-point scales. Concerning well-being, we examine loneliness, depression, mental health, vitality, emotional well-being, social activity, social quality, and social functioning. Notably, the mental health index is also known as ‘psychological function’; however, for ease of interpretation, we use the more commonly used index name, ‘mental health’. All indices are increasing in their respective names, hence, we hypothesized that with the exception of loneliness and depression, which should be negatively impacted, the treatment would increase these measures.

Concerning physical health, in addition to poor health and the number of medications taken (excluding vitamins), we observe: general health, basic and intermediate levels of physical functioning, overall physical functioning, physical role, and bodily pain. Notably, poor health is a dichotomous variable based on self-reported levels of health (equals unity if the respondent reported fair/poor health; zero otherwise). With the exception of poor health, bodily pain, and number of medications taken, which we expected to have been negatively impacted, we posited that the intervention would increase these indices. presents baseline descriptive statistics for all outcomes.

Table 2. Baseline outcome descriptive statistics.

In addition to assuring participant confidentiality, a series of follow-up waves of data collection also allowed us to mitigate potential concerns over a Hawthorne Effect—i.e. a situation whereby individuals adjust their behaviours/responses as a result of being directly observed and aware of the overarching hypotheses. Further, participants were allowed to skip any questions they did not wish to answer. Thus, anonymity, the right of refusal, and a series of follow-up surveys should have helped respondents feel more comfortable with providing truthful responses. Lastly, it should be noted that during the first and second waves of data collection, participants were administered paper copies of the above surveys. However, due to COVID-19, an online version of the questionnaires was created. Depending on preferences and public health protocols, the online version provided an additional method of surveying respondents in waves 3, 4, and 5.

Identification strategy

Ordinary least squares

For each index and health indicator, a set of regressions examine both between- and within-group variation in outcomes over the study period using ordinary least squares (OLS). As a robustness check, a probit/logit specification in the case of poor health, and a Poisson regression in the case of number of medications, were tested using methods outlined by Puhani (Citation2012). Results are akin to those produced using OLS; thus, for interpretation and brevity purposes, only OLS estimates are presented. Exploiting the randomized aspect of our study, we are able to examine how the intervention impacted programme participants, relative to the control group. Thus, controlling for the treatment group (ART), along with time over which the study occurred (T), and an interaction of these terms (ART × T), allows for a causal interpretation of programme impact—i.e. the treatment effect estimator.

As noted by Twisk et al. (Citation2018), while some have argued that controlling for being in the intervention group at baseline is not necessary, given random assignment means that any statistical difference is merely due to chance, this omission fails to account for regression to the mean. Hence, the current preferred method includes such baseline controls. Additionally, while they also advocate for a lagged dependent variable in the regression model, we include a set of observable characteristics to improve upon precision (see: Deaton and Cartwright (Citation2018) and Kahan et al. (Citation2014) regarding such methods). However, alternative modelling strategies that control for baseline outcomes in lieu of baseline controls, reveal similar findings; results are available upon request.

Given that data were collected over five time periods, we have the option of defining time in continuous or discrete terms. When time is captured in continuous terms, the variable takes on one of five values, which for simplicity purposes equal: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. In the discrete version, T is a set of four dummy variables (with baseline data being the reference category), each equaling unity if the observation occurred in that respective time period; zero otherwise. In both instances, the specification of the treatment effect is a reflection of how time is defined—however, regardless of choice, the objective of comparing group trajectories is maintained. While the discrete version is more flexible (the continuous model assumes a linear trajectory), it does require a larger set of explanatory variables, reducing the degrees of freedom, and thereby increasing the probability of a type II error. Since both have advantages and disadvantages, we examine both options.

Our inferential model, in continuous terms, is specified such that for individual i in time t, outcome y concerning index j is regressed on the following covariates:

(1)

(1)

In turn, the discrete version can be characterized as:

(2)

(2)

To improve upon the precision of our key estimates, we include a set of control variables (X) which were collected before the onset of the programme. In terms of socioeconomic factors, we control for annual household income (specified in natural log terms, and given no one reported a zero (or negative) dollar income, no observations were lost given this transformation), along with the respondent’s highest level of education (i.e. a high school education or less, some post-secondary, a college diploma, a Bachelor’s degree, or a graduate/professional degree). The demographic variables include age, marital status (i.e. single, divorced/separated, married, or widowed), gender, and whether or not the respondent is an immigrant and/or visible minority. Additionally, to ensure that our results are not endogenously determined, we also include a dummy variable that captures, in each time period, whether or not the respondent recently joined any other organization(s), which also helps adjust for a potential John Henry Effect—i.e. a change in behaviour by the control group, given they were not chosen for the intervention. Lastly, the error term (e) in both instances is assumed to be idiosyncratic.

Quantile regression

OLS produces a set of estimates by conditioning on the mean of an outcome variable and is a very commonly used method when estimating the effects of a programme. However, results for specific groups of the outcome variable are not possible without first truncating the model to establish the new group-specific mean value. This loss of observations causes inflated standard errors, especially when certain regions of the distribution lack observations. Conversely, re-centered influence functions using quantile regression do not require the need for truncation, and can therefore produce more efficient estimates of programme efficacy at differing points of the outcome distribution (Koenker & Hallock, Citation2001).

From a policy perspective, there is plausibly less incentive to pursue programming if the benefits primarily occur among those with already high levels of health and well-being. However, if the reverse is true, such that the benefits are most demonstrable among those with a dearth of health and/or well-being, then there may be more reason to support such initiatives. Moreover, as illustrates, mean outcomes tend to suggest that the sample had rather high levels of initial health and well-being—a result not unlike those found in a series of Canadian mental health studies by Watson and Osberg (Citation2017, Citation2018) and Watson et al. (Citation2020). Allowing for a re-centered examination of both those more and less health-fortunate, we extend EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) to include quantile regressions that estimate the treatment effect using weighted least squares at 5 percentage point intervals (i.e.

).Footnote6

(3)

(3)

Results

OLS results

Two sets of 16 regressions are run based on themes of well-being and physical health, with goodness-of-fit values typically exceeding 10%. The first set of regression estimates is derived having specified time in continuous terms; the second set specifies time in discrete terms. The set of control variables outlined in the previous section is included in all regressions. Given that respondents were observed multiple times throughout the study period, standard errors are clustered by an individual to account for potential heteroskedasticity and cluster effects ( for

).

Since each index was derived using different recommended methods to deal with missing data, observation numbers differ across regressions, ranging from 443 (social activity) to 539 (social quality). Likewise, the question concerning the number of medications was only asked in waves 2–5 (n = 402). While art session attendance was generally strong and consistent, we exclude 12 outlier participants who missed the overwhelming majority of art classes (i.e. 66% or more), which as noted below, provides further evidence regarding the efficacy of our arts-based intervention. Removal of these participants does not cause the control and treatment groups to statistically differ based on observational data; comparisons are available from the lead author upon request.

Key results concerning the model where time is specified in continuous terms are presented in , with the full set of regression results available in Tables A1 and A2 of the Supplementary Online Appendix. Panel (a) depicts the well-being estimates and Panel (b) concerns physical health estimates. Given that the indices presented in these tables are on 100-point scales, parameter estimates can be interpreted as percentage point changes. In turn, since poor health is a dichotomous variable, parameter estimates in this instance capture response probabilities. Lastly, number of medications (excluding vitamins) is a count variable.

Table 3. Key regression results: continuous time.

Relative to the control group, there appears to have been a statistically significant improvement in the well-being of those participating in the arts-based programme. In most instances, the interaction term is statistically (and economically) significant at conventional levels. More specifically, aside from social activity and social functioning, those participating in the programme are expected to have incurred a 1–2 percentage point improvement in each of the well-being indices when compared with the control group. This indicates, on average, less loneliness and depression, better mental health, more vitality, a higher level of emotional well-being, and improved quality of social interactions.

Although we observe an improvement in well-being among programme participants, the same does not necessarily apply to physical health. Regression results suggest that the intervention did not reduce the probability of the respondent being in poor health. It also did not reduce reports of bodily pain or the number of medications taken. In all instances, parameter estimates are small and have large standard errors, implying both economic and statistical insignificance. However, there seems to be a certain degree of improvement in physical functioning. The treatment group is expected to have experienced a 1–2 percentage point increase in basic and intermediate levels of physical functioning. While the former result is not of major interest, given the mean index value is about 95 (on a 100-point scale), the latter result is of greater importance given a much lower mean (≈80) and complex task list (e.g. walking several blocks, grocery shopping, climbing stairs).

Key regression results concerning time specified in discrete terms are presented in and support the previous findings.Footnote7 Notably, improvements, particularly with respect to well-being, tended to occur in the later time periods of the intervention. These results imply that it was the intervention that was producing a rise in well-being; not the recommencement of general social activity. If our results were capturing the latter, would consist of a series of parameter estimates that would be largest in time period 2, monotonically decreasing thereafter—i.e. results would suggest people were habituating to a consistent stretch of social activity. Conversely, an effective programme would likely produce statistically (and economically) insignificant results in time period 2 given: (i) the stoppage time between classes and being subsequently surveyed, and (ii) the fact that the programme was still relatively new.

Hence, not only do these findings support our previous results, but they also suggest that benefits continued to manifest over the course of the study. In particular, larger magnitudes of effect—in the vicinity of 5–10 percentage points, as shown in Panel (a)—occur toward the end of the programme. Moreover, in terms of physical health, intermediate functioning is expected to have improved by as much as 10 percentage points by the end of the study (see Panel (b)). Thus, we conjecture that improvements in physical functioning may have flow-on effects, manifesting in higher levels of physical health and reduced medication use, should the intervention have extended over a longer period of time.

Finally, it is worth noting that when we do not exclude those 12 programme participants with poor attendance levels, the treatment effect, in virtually all cases, is statistically insignificant. This provides further evidence that the programme was indeed impactful and not merely an artifact of the data. Thus, it is not only the existence of an arts-based programme that matters, as absenteeism reduced effectiveness. Therefore, future programming should ensure that participants have adequate means to attend art sessions, which may include flexible session times and the provision of transportation.

Quantile regression results

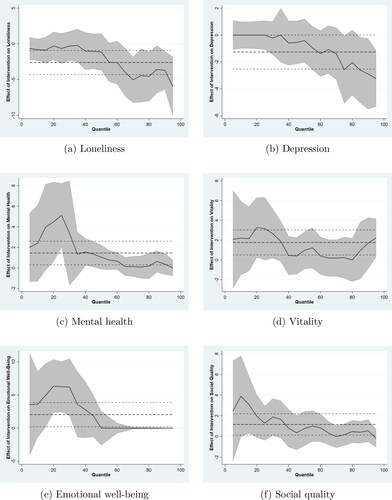

Like OLS results, quantile regression findings tend to suggest that the intervention had a positive impact on the well-being of seniors; but, physical health estimates are, for the most part, statistically insignificant. Concerning well-being, quantile regression results tend to show that point estimates are monotonically decreasing—i.e. programme benefits are primarily driven by those with low levels of well-being. With respect to physical health outcomes, it would appear that linear regressions that condition on the mean did not mask treatment effect estimators that follow a ‘u’ or ‘inverted-u’ across outcome quantiles.

Regarding loneliness and depression, the programme seems to have been most effective for those in the top quartile of these indices, with respective declines of about 4–5 percentage points and 2–3 percentage points. Thus, the more lonely or depressed, the greater the predicted impact. Among those in the respective bottom quartiles of the mental health, emotional well-being, and social quality distributions, effect sizes are about 2–4, 4–5, and 2–4 percentage points. Vitality results are similar and also suggest that the largest (and statistically significant) improvements were for those in the bottom quartile. It would therefore seem that effect sizes for those in the above quartiles are about double those which condition on the mean, suggesting that the art-based endeavour tended to most benefit those with poor levels of well-being.

Programme effects on (a) loneliness, (b) depression, (c) mental health, (d) vitality, (e) emotional well-being, and (f) quality of social interactions are depicted in . The horizontal axis denotes outcome quantile in each panel, and vertical axes captures treatment effects with 95% confidence intervals depicted in greyscale. For ease of comparison, OLS coefficients and 95% confidence intervals are presented using dashed lines. Quantile regression results for the other two well-being indices line up strongly with the OLS estimate—i.e. results are statistically insignificant with small point estimates that have large standard errors, implying that OLS results are not merely an artifact of offsetting negative and positive effects at different ends of the outcome distributions.

Discussion and conclusion

Hanna et al. (Citation2015) argue that although there has been an uptick in the quality of research studies examining creative ageing and its impact on elderly populations, there is still a need for more analyses that employ experimental designs and an extensive range of standardized outcomes. We addressed this call to action by recruiting 252 seniors living in the eastern Canadian city of Saint John to participate in a 12-month arts-based randomized controlled trial. This intervention included active participation in a series of artistic endeavours which included drawing, painting, collage, clay-work, performance, sculpting, and mixed media. Of those recruited, 130 were randomly assigned to the treatment group, with the remaining 122 serving as control. Although the onset of COVID-19 coincided with the launch of our programme, the intervention was able to safely run, in-person, over a 16-month period (January 2020—April 2021).

To examine the extent to which this art-based endeavour impacted the health and well-being of participants, respondents in both the intervention and control groups were administered the following standardized surveys at five time-points (December 2019, July/August 2020, November 2020, March 2021, May 2021): the UCLA Loneliness Scale, the Geriatric Depression Scale, the Functional Status Questionnaire, and the SF-36v2 Health Survey. Attrition is a typical concern in such studies and COVID-19 intensified the number of people dropping out of the study (i.e. almost half of the attrition can be linked to concerns over the onset of COVID-19). Although about 47% of the initial sample failed to complete all five rounds of data collection, and although the attrition rate for the control group was almost double the treatment, observable baseline differences between these two groups remained statistically insignificant.

Our results corroborate Cohen’s (Citation2006) seminal finding that artistic programming positively impacts the health and well-being of seniors. Despite the psychological stressors stemming from the pandemic, our estimates using a series of regression models suggest that the arts-based intervention enriched well-being, and to a lesser degree, bettered the physical health of senior citizens. Moreover, these improvements are predicted to have increased in magnitude over the course of the study and tend to be most pronounced for those who suffered from low levels of well-being. Relative to our control group, feelings of loneliness and depression are expected to have decreased. Additionally, mental health, levels of vitality, and emotional well-being are predicted to have improved, and programme participants also tended to report higher quality social interactions.

Those who participated in the programme were also more likely to have experienced relative increases in physical functioning, although self-reported health, bodily pain, and the number of medications taken did not statistically change relative to the control. To improve upon the precision of our estimates, socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, which may have impacted participant health and well-being, were included in the model. Additionally, to minimize bias resulting from a John Henry Effect, whereby the control group systematically reacts to being left out of the study, we also adjusted for the respondent joining other organizations (a response that may be more likely among those not selected for the arts-based intervention). Notably, key results are robust to such inclusions.

Our primary recommendation is that such programmes be continued on a greater scale as our findings corroborate past evidence, which is especially noteworthy given COVID-19 likely attenuated our conclusions. Indeed, when examining responses during March 2021, when the city had just experienced a brief lock-down, there were apparent decreases in well-being for both the intervention and control groups. While the impacts of the pandemic were unlikely distributed differently between groups, given the heightened vulnerability of the elderly to this virus, these positive results indicate a degree of offsetting against a generationally unprecedented event that caused great distress and uncertainty. As such, we argue that arts-based programming that emphasizes creative ageing is an efficacious intervention concerning the well-being of the elderly. Perhaps this is best illustrated by the fact that the positive well-being impacts of this programme were largely driven by those with the highest levels of depression and/or loneliness, along with a dearth of mental health, vitality, emotional well-being, and/or quality interaction.

Second, our work finds that those with higher session attendance rates were more likely to report improved health and well-being outcomes. This result highlights the efficacy of the intervention, reducing concerns that key estimates are spuriously determined. Therefore, we recommend that future programming not only stress the importance of attending such interventions but also minimize potential impediments concerning session attendance (e.g. provision of transportation, flexible programming hours, etc.).

As stated by Lazar et al. (Citation2016), arts-based interventions that promote creative ageing are now being advocated by therapists when working with seniors. Likewise, Chilton and Wilkinson (Citation2009) argue that healthy ageing can be further enhanced by focusing the art provider’s techniques toward such positive outcomes—hence, future programming may wish to consider the importance of not only the type of content being delivered but also how it is delivered. As with any study taking place in a specific geographic area that consists of a limited number of observations, external validity is a concern—i.e. would our findings be similar, should this study have taken place in a different region? While, our study adds to the knowledge base that generally argues in favour of such endeavours, future programming may wish to continue such pursuits by (i) running randomized controlled trials in other parts of Canada as a means of comparison, and/or (ii) analyzing national-level secondary data, that has the benefit of large sample sizes, to examine the casual effects of potentially comparable interventions.

Our results highlight an ongoing health and well-being improvement that corroborates past evidence on this topic. We recommend that arts-based programmes which promote creative ageing be offered as going concerns, with minimal interruptions. While the onset of COVID-19 was unforeseen, the interruptions in session offerings undoubtedly worked against our overarching hypothesis of healthy ageing. Additionally, the pandemic tended to be particularly distressing for those with health vulnerabilities, meaning that the impact on senior populations was likely more acute. Consequently, our intervention was effective, even during such trying times, revealing just how valuable creative ageing can be for the elderly. We believe results would have been much larger in magnitude had the programme been offered in less extraordinary times. The arts matter.

Ethical approval

Research Ethics Board of the University of New Brunswick, project number 002-2020.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (334.6 KB)Disclosure statement

Anita Punamiya is the founder and CEO of Art4Life Inc. and Alekhya Das was employed by this social enterprise; however, the organization is not currently active. The remaining authors have no interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We recognize that those already exposed to the arts may have been more inclined to volunteer for this study. However, an informal poll suggests that most did not participate in artistic endeavours on a regular basis. In fact, for some participants, this was their first encounter with an arts-based activity. Likewise, no one reported having a professional background in the arts.

2 Prior to the programme, each artist received training in working with the elderly. As noted in section Discussion and conclusion, Chilton and Wilkinson (Citation2009) argue that such training can enhance positive outcomes.

3 For instance, the second block consisted of: creative movement, water colour painting, sculpting, and mixed media.

4 Online sessions were not offered as they would have caused material deviation from the originally intended provision of in-person, group-based activity. Moreover, many participants were not technologically equipped to access online programmes and others were averse to such methods.

5 Over 45% of the attrition came after the March 2020 lock-down. Additionally, about 33% of the attrition occurred after we announced group membership—i.e. many in the control group dropped out upon learning they had not been randomly selected. To our knowledge, the bulk of attrition was not due to health issues or death.

6 Extending EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2) to include quantile regressions methods, produces similar results; thus, for brevity purposes, we focus on estimates where time is defined in continuous terms. Quantile regression results, whereby time is defined in discrete terms, are available from the lead author upon request.

7 The complete set of results are very much akin to those presented in Tables A1 and A2.

References

- Adams-Price, C. E., Nadorff, D. K., Morse, L. W., Davis, K. T., & Stearns, M. A. (2018). The creative benefits scale: Connecting generativity to life satisfaction. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 86(3), 242–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415017699939

- Alders, A., & Levine-Madori, L. (2010). The effect of art therapy on cognitive performance of Hispanic/Latino older adults. Art Therapy, 27(3), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2010.10129661

- Alders-Pike, A. (2013). The effect of art therapy on cognitive performance among ethnically diverse older adults. Art Therapy, 30(4), 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2014.847049

- Balyasnikova, N., & Gillard, S. (2021). “They gave me back my power”: Strengthening older immigrants’ language learning through arts-based activities. Studies in the Education of Adults, 53(2), 220–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2021.1911109

- Beauchet, O., Lafleur, L., Remondière, S., Galery, K., Vilcocq, C., & Launay, C. P. (2020). Effects of participatory art-based painting workshops in geriatric inpatients: Results of a non-randomized open label trial. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 32(12), 2687–2693. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-020-01675-0

- Bernard, M., & Rickett, M. (2017). The cultural value of older people’s experiences of theater-making: A review. The Gerontologist, 57(2), e1–e26.

- Bugos, J. A. (2014). Community music as a cognitive training programme for successful ageing. International Journal of Community Music, 7(3), 319–331. https://doi.org/10.1386/ijcm.7.3.319_1

- Chapwell, C. (2014). Bring on the health economists: Time for a rigorous evaluation of senior participative arts. Working with Older People, 18(1), 4–9. https://doi.org/10.1108/WWOP-11-2013-0028

- Chilton, G., & Wilkinson, R. (2009). Positive art therapy: Envisioning the intersection of art therapy and positive psychology. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Art Therapy, 4(1), 27–35.

- Cohen, G. (2006). Research on creativity and aging: The positive impact of the arts on health and illness. Generations, 30(1), 7–15.

- Cohen, G. (2009). New theories and research findings on the positive influence of music and art on health with ageing. Arts & Health, 1(1), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533010802528033

- de Medeiros, K. (2009). Suffering and generativity: Repairing threats to self in old age. Journal of Aging Studies, 23(2), 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2008.11.001

- Deaton, A., & Cartwright, N. (2018). Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials. Social Science & Medicine, 210, 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.005

- Dunphy, K., Baker, F. A., Dumaresq, E., Carroll-Haskins, K., Eickholt, J., Ercole, M., Kaimal, G., Meyer, K., Sajnani, N., Shamir, O. Y., & Wosch, T. (2018). Creative arts interventions to address depression in older adults: A systematic review of outcomes, processes, and mechanisms. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2655. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02655

- Ehresman, C. (2014). From rendering to remembering: Art therapy for people with Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Art Therapy, 19(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2013.819023

- Fancourt, D., & Steptoe, A. (2019). The art of life and death: 14 year follow-up analyses of associations between arts engagement and mortality in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. BMJ, 367, l6377. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6377

- Fields, N., Xu, L., Greer, J., & Murphy, E. (2021). Shall I compare thee… to a robot? An exploratory pilot study using participatory arts and social robotics to improve psychological well-being in later life. Aging & Mental Health, 25(3), 575–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1699016

- Flood, M., & Phillips, K. D. (2007). Creativity in older adults: A plethora of possibilities. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 28(4), 389–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840701252956

- Fraser, K. D., O’Rourke, H. M., Wiens, H., Lai, J., Howell, C., & Brett-MacLean, P. (2015). A scoping review of research on the arts, aging, and quality of life. The Gerontologist, 55(4), 719–729. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnv027

- Gutheil, I. A., & Heyman, J. C. (2016). Older adults and creative arts: Personal and interpersonal change. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 40(3), 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2016.1194030

- Hanna, G. P., Noelker, L. S., & Bienvenu, B. (2015). The arts, health, and aging in America: 2005–2015. The Gerontologist, 55(2), 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu183

- Ho, A. H. Y., Ma, S. H. X., Ho, M. H. R., Pang, J. S. M., Ortega, E., & Bajpai, R. (2019). Arts for ageing well: A propensity score matching analysis of the effects of arts engagements on holistic well-being among older Asian adults above 50 years of age. BMJ Open, 9(11), e029555. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029555

- Jette, A. M., Davies, A. R., Cleary, P. D., Calkins, D. R., Rubenstein, L. V., Fink, A., Kosecoff, J., Young, R. T., Brook, R. H., & Delbanco, T. L. (1986). The functional status questionnaire: Reliability and validity when used in primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1(3), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02602324

- Johnson, C. M., & Sullivan-Marx, E. M. (2006). Art therapy: Using the creative process for healing and hope among African American older adults. Geriatric Nursing, 27(5), 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2006.08.010

- Johnson, J. K., Carpenter, T., Goodhart, N., Stewart, A. L., Du Plessis, L., Coaston, A., Clark, K., Lazar, A., & Chapline, J. (2021). Exploring the effects of visual and literary arts interventions on psychosocial well-being of diverse older adults: A mixed methods pilot study. Arts & Health, 13(3), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2020.1802603

- Kahan, B. C., Jairath, V., Dore, C. J., & Morris, T. P. (2014). The risks and rewards of covariate adjustment in randomized trials: An assessment of 12 outcomes from 8 studies. Trials, 15, 139. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-15-139

- Kasar, K. S., & Karaman, E. (2021). Life in lockdown: Social isolation, loneliness and quality of life in the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Geriatric Nursing, 42(5), 1222–1229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.03.010

- Keisari, S., Palgi, Y., Yaniv, D., & Gesser-Edelsburg, A. (2020). Participation in life-review playback theater enhances mental health of community-dwelling older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 16(2), 302–317. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000354

- Koenker, R., & Hallock, K. F. (2001). Quantile regression. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(4), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.15.4.143

- Lawton, P. H., & La Porte, A. M. (2013). Beyond traditional art education: Transformative lifelong learning in community-based settings with older adults. Studies in Art Education, 54(4), 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2013.11518905

- Lazar, A., Cornejo, R., Edasis, C., Piper, A. M. (2016). Designing for the third hand: Empowering older adults with cognitive impairment through creating and sharing. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems (pp. 1047–1058).

- Liddle, J. L., Parkinson, L., & Sibbritt, D. W. (2012). Painting pictures and playing musical instruments: Change in participation and relationship to health in older women. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 31(4), 218–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6612.2011.00574.x

- Liu, C., Su, M., Jiao, Y., Ji, Y., & Zhu, S. (2021). Effects of dance interventions on cognition, psycho-behavioral symptoms, motor functions, and quality of life in older adult patients with mild cognitive impairment: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 13, 706609. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.706609

- McFadden, S. H., & Basting, A. D. (2010). Healthy aging persons and their brains: Promoting resilience through creative engagement. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 26(1), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2009.11.004

- Mirzada, F., Schimberg, A. S., Engelaer, F. M., Bijwaard, G. E., van Bodegom, D., Westendorp, R. G., & van Poppel, F. W. (2014). Arts and ageing; life expectancy of historical artists in the low countries. PLOS One, 9(1), e82721. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082721

- Noice, H., Noice, T., & Staines, G. (2004). A short-term intervention to enhance cognitive and affective functioning in older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 16(4), 562–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264304265819

- Noice, T., Noice, H., & Kramer, A. F. (2014). Participatory arts for older adults: A review of benefits and challenges. The Gerontologist, 54(5), 741–753. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt138

- Palmiero, M., Di Giacomo, D., & Passafiume, D. (2016). Can creativity predict reserve? The Journal of Creative Behavior, 50(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.62

- Poulos, R. G., Marwood, S., Harkin, D., Opher, S., Clift, S., Cole, A. M. D., Rhee, J., Beilharz, K., & Poulos, C. J. (2019). Arts on prescription for community-dwelling older people with a range of health and wellness needs. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(2), 483–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12669

- Puhani, P. A. (2012). The treatment effect, the cross difference, and the interaction term in nonlinear “difference-in-differences” models. Economics Letters, 115(1), 85–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2011.11.025

- Rodrigues, L. M., Smith, A. P., Sheets, D. J., & Hémond, J. (2019). The meaning of a visual arts program for older adults in complex residential care. Canadian Journal on Aging, 38(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980818000508

- Rolfson, D. B., Majumdar, S. R., Tsuyuki, R. T., Tahir, A., & K, R. (2006). Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age and Ageing, 35(5), 526–529. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afl041

- Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Ferguson, M. L. (1978). Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42(3), 290–294. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11

- Sabeti, S. (2015). Creative ageing? Selfhood, temporality and the older adult learner. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 34(2), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2014.987710

- Sheikh, J. I., & Yesavage, J. A. (1986). Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontologist, 5(1–2), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1300/J018v05n01_09

- Southcott, J., & Li, S. (2018). “Something to live for”: Weekly singing classes at a Chinese university for retirees. International Journal of Music Education, 36(2), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761417729548

- Twisk, J., Bosman, L., Hoekstra, T., Rijnhart, J., Welten, M., & Heymans, M. (2018). Different ways to estimate treatment effects in randomised controlled trials. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, 10, 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2018.03.008

- Ueno, K., Takahashi, T., Takahashi, K., Mizukami, K., Tanaka, Y., & Wada, Y. (2015). Neurophysiological basis of creativity in healthy elderly people: A multiscale entropy approach. Clinical Neurophysiology, 126(3), 524–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2014.06.032

- Wakeling, K., & Clark, J. (2015). Beyond health and well-being: Transformation, memory and the virtual in older people’s music and dance. International Journal of Ageing and Later Life, 9(2), 7–34. https://doi.org/10.3384/ijal.1652-8670.15262

- Wang, S., Mak, H. W., & Fancourt, D. (2020). Arts, mental distress, mental health functioning & life satisfaction: Fixed-effects analyses of a nationally-representative panel study. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 208. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8109-y

- Ware, J. E., Snow, K. K., Kosinski, M., & Gandek, B. (1993). SF-36 Health Survey. Manual and interpretation guide. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center.

- Watson, B., & Osberg, L. (2017). Healing and/or breaking? The mental health implications of repeated economic insecurity. Social Science & Medicine, 188, 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.042

- Watson, B., & Osberg, L. (2018). Job insecurity and mental health in Canada. Applied Economics, 50(38), 4137–4152. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2018.1441516

- Watson, B., Daley, A., Rohde, N., & Osberg, L. (2020). Blown off-course? Weight gain among the economically insecure during the Great Recession. Journal of Economic Psychology, 80, 102289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2020.102289

- Wilson, D. M., Osei-Waree, J., Hewitt, J. A., & Broad, A. (2012). Canadian provincial, territorial, and federal government aging policies: A systematic review. Advances in Aging Research, 1(2), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.4236/aar.2012.12005

- Yu, J., Rawtaer, I., Goh, L. G., Kumar, A. P., Feng, L., Kua, E. H., & Mahendran, R. (2021). The art of remediating age-related cognitive decline: Art therapy enhances cognition and increases cortical thickness in mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 27(1), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617720000697