Abstract

Objectives

To synthesize evidence relevant for informed decisions concerning cognitive testing of older physicians.

Methods

Relevant literature was systematically searched in Medline, EMBASE, PsycInfo, and ERIC, with key findings abstracted and synthesized.

Results

Cognitive abilities of physicians may decline in an age range where they are still practicing. Physician competence and clinical performance may also decline with age. Cognitive scores are lower in physicians referred for assessment because of competency or performance concerns. Many physicians do not accurately self-assess and continue to practice despite declining quality of care; however, perceived cognitive decline, although not an accurate indicator of ability, may accelerate physicians’ decision to retire. Physicians are reluctant to report colleagues’ cognitive problems. Several issues should be considered in implementing cognitive screening. Most cognitive assessment tools lack normative data for physicians. Scientific evidence linking cognitive test results with physician performance is limited. There is no known level of cognitive decline at which a doctor is no longer fit to practice. Finally, relevant domains of cognitive ability vary across medical specialties.

Conclusion

Physician cognitive decline may impact clinical performance. If cognitive assessment of older physicians is to be implemented, it should consider challenges of cognitive test result interpretation.

Introduction

Aging affects the entire human body, and changes in cognitive functioning are among the most noticeable features of growing old (Cohen et al., Citation2019). Decline in cognitive functions associated with aging cannot always be attributed to pathological processes in the brain, such as neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. For example, most older adults process information slower than they did when they were younger (Institute of Medicine, 2015). Normal cognitive aging is ‘a process of gradual, ongoing, yet highly variable changes in cognitive functions that occur as people get older. Cognitive aging is a lifelong process. It is not a disease or a quantifiable level of function’ (Institute of Medicine, 2015) (p. 2). While evidence suggests that neurodegeneration leading to Alzheimer’s disease spans decades (Braak et al., Citation2006), the boundary between normal age-associated cognitive changes and the initial phase of a neurodegenerative disorder is not well understood. Distinguishing between normal and pathological changes may be challenging (Institute of Medicine, 2015). Transition from normal cognition to mild cognitive impairment has not been well studied, though evidence supports several health and lifestyle factors as predictors (Cherbuin et al., Citation2009).

Many cognitive functions decline in older adults, although there is great variability between individuals. Areas of decline include speed of information processing, selective attention, divided attention (multitasking), working memory, episodic memory, prospective memory, source memory (the ability to remember contextual aspects of an experience), executive functioning, reasoning ability, and spatial ability (Cohen et al., Citation2019; Glisky, Citation2007; Institute of Medicine, 2015). In contrast, other functions remain relatively stable over the lifespan, including sustained attention (or vigilance), semantic long-term memory (the ability to store general knowledge about the world acquired over a lifetime), and wisdom (a multidimensional construct) (Cohen et al., Citation2019; Glisky, Citation2007; Institute of Medicine, 2015). Procedural memory (remembering how to perform an activity) and language functions are only partially affected in old age. Older adults are good at performing automatic or well-learned procedures and can learn new procedures; however, they may be slower when performing familiar tasks and may learn new procedures at a slower rate than younger adults (Glisky, Citation2007; Institute of Medicine, 2015). There is evidence that discourse skills improve with age; vocabulary and word comprehension remain stable, whereas language production skills appear to decline (Glisky, Citation2007; Institute of Medicine, 2015).

Despite high education levels and careers that require constant and involved mental aptitude, physicians are not immune to age-related changes in cognitive function. Many physicians continue to practice beyond age 65, and there exists concern that cognitive impairment may undermine patient safety (Dellinger et al., Citation2017). For instance, the Quality in Australian Health Care Study reported that failure of cognitive function was the second most frequent cause of errors in the delivery of healthcare that led to adverse events in patients (Wilson et al., Citation1999).

The current review aimed to synthesize evidence on cognitive decline in aging physicians and its relation to clinical competency. The results of the review will serve to guide policy on possible implementation of cognitive screening of physicians. The review focused on scientific evidence; ethical, legal, and financial considerations were beyond the scope of the review.

Methods

Literature was searched in Medline, Embase, PsycInfo, and Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) in July-August 2022. The search strategy was developed for Medline (See Appendix, ) and then adapted for other databases. Bibliographies of review articles were inspected for additional references. References identified from all sources underwent two levels of screening: title and abstract (level 1) and assessment of full text (level 2) based on pre-defined eligibility criteria. Eligible were systematic reviews and original studies that included older physicians of any specialty, and objective measures of cognitive functioning or clinical competence or performance.

Table 1. Studies of the relationship between physician age or years in practice and competence or performance.

Table 2. Studies of cognitive functioning of physicians referred for assessment due to clinical competency or performance concerns.

Additional eligibility criteria were applied to studies that examined associations between physicians’ age and their clinical competence or performance. These studies had to include two or more age categories older than ∼50 years and at least one category younger than 50 years. Studies with age measured as a continuous variable needed to include physicians aged from less than ∼50 years to ∼70 years or older. Additionally, analyses had to be adjusted for potential confounders, such as characteristics of the physician (other than age), the patients, and the clinical practice.

Results

Does aging affect physician cognition and the ability to practice competently and safely?

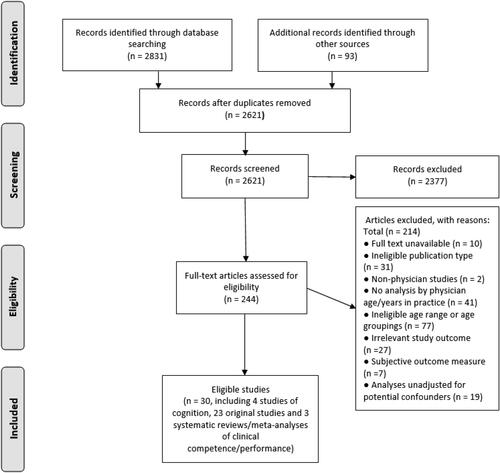

A PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., Citation2009) detailing the study selection process is shown in .

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram for studies of age-related changes in physicians’ cognition or their clinical performance/competence.

Physician age and cognitive functioning

Four studies were identified, of which three included subsets of the same study population. Additional details on these studies can be found in Appendix ().

Bieliauskas et al. (Citation2008) used the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) to assess 359 surgeons aged 45–86 years. Visual sustained attention and stress tolerance in the rapid visual information processing (RVIP) task, reaction time (RTI task), and visual learning and memory in the paired associates learning (PAL) task declined with increasing physician age; the decline was most pronounced in age groups over 70 years, although some functions showed an earlier decline, from ages 60. When surgeons were retested one to six years after initial testing, an increase in mean latency of response on the RVIP task was observed with no significant changes in accuracy. There was a decrease in number of errors per trial on the PAL task, which the authors explained by test familiarity or the practice effect (Bieliauskas et al., Citation2008).

Boom-Saad et al. (Citation2008) analyzed data on 308 practicing surgeons from the same dataset, where surgeons were divided into two age groups: 139 mid-career surgeons (45–60 years) and 169 senior surgeons (61–75 years). Their performance on the three tasks was compared with normative age-matched controls and also with the performance of 20 to 35-year-old surgical trainees. The performance of senior surgeons on all three neuropsychological tests was inferior to that of mid-career surgeons and of surgical trainees. Senior surgeons outperformed the age-matched normative control only on one of the two parameters of the RTI test, whereas the performance of mid-career surgeons and surgical trainees was significantly better than that of age-matched normative controls on both the RTI and RVIP tests.

Drag et al. (Citation2010) studied the cognitive status of the same surgeons in relation to their retirement status. Their analysis included data on 168 senior surgeons (60+ years) and 126 younger surgeons (45–59 years). Of the senior surgeons, 36% had retired, 33% were planning to retire within 5 years, and 30% had no imminent retirement plans. It was found that 55% of all senior surgeons, 49% of senior surgeons with no imminent plans to retire, 72% of senior surgeons planning to retire within the next 5 years, and 45% of retired surgeons performed within the range of the younger surgeons on all three cognitive tasks. No senior surgeon performed below the younger surgeons on all three tasks. This study demonstrated that many senior surgeons performed at or near the level of younger surgeons on cognitive tasks, suggesting that older age does not necessarily affect cognition.

Using the computerized cognitive test, MicroCog, Powell and Whitla (Citation1994) assessed cognition of 1,002 physicians and 581 other subjects (referred to as normal subjects). The physicians ranged from 25 to 92 years of age, and normal subjects from 25 to 83 years. The MicroCog test measures reactivity, attention, numeric recall, verbal memory, visuospatial facility (the individual’s capacity to identify visual and spatial relationships among objects), reasoning, and mental calculation. Physician total MicroCog scores gradually declined between 30 and 60 years of age, with a more rapid decline after 60 years of age. Among the normal subjects, the total MicroCog score declined more rapidly after age 50; in the two decades after age 60, their scores were similar to those of physicians ten years older. The gap between the two groups narrowed after age 75; however, at all ages, the normal subjects scored lower than the physicians. As to specific cognitive functions, similar patterns were seen for the physicians and the normal subjects. Visuospatial scores showed the steepest decline, followed by reasoning scores (decline in reasoning scores of physicians occurred about a decade later than the decline in visuospatial scores), and then verbal memory. More resistant to aging were calculation skills (math scores) and attention. Specific abilities, as well as global cognitive functioning, showed a relatively mild decline until age 70–74 years and a more marked decline at 75–79 years. No significant age-related changes were seen for reaction times, which was not consistent with most of the literature. The discrepancy may be explained by either relatively less demanding tasks used in this study or by the older study participants being not representative of their age group (Powell & Whitla, Citation1994). This study also demonstrated a significant variability in cognitive performance among physicians aged 65 years and older, with a substantial number of older physicians functioning at a level close to that of younger subjects.

In summary, studies reviewed in this section demonstrated a decline in cognitive functioning of older physicians detectable at about 60 years, which is 10 years later than in the general population. This is likely due to physicians’ higher educational level and intellectually demanding occupation, factors that increase and maintain cognitive reserve (Stern et al., Citation2020). Cognitive reserve poses a possible issue for interpretation of results, e.g. appropriateness of using age-matched general population data for comparison (Turnbull et al., Citation2006). There was a substantial inter-individual variability in older physicians’ cognitive functioning. It should be noted that, because all these studies are cross-sectional, a causal association cannot be inferred between the observed differences in test scores and physician age. These differences in cognitive performance may also be related to other unaccounted differences between the age groups. Although cross-sectional data are generally adequate to answer the question about age-related cognitive decline, they may overestimate both the magnitude of the decline and how early the decline occurs (Powell & Whitla, Citation1994).

Physicians’ age and ability to practice competently and safely

Two related concepts were considered: competence and performance. Competence reflects how physicians perform in a controlled environment, specifically in testing situations such as a written examination or Objective Structured Clinical Examination. Physicians acquire competence through medical school and residency/fellowship training, and on passing qualifying medical licensure examinations. Performance represents how physicians apply their attitudes, knowledge, and skills in a multidimension practice context that is impacted by many factors. Competence is necessary but not sufficient for high-quality physician performance (Kain et al., Citation2019; Rethans et al., Citation2002). There is some uncertainty regarding the informativeness of competence assessments noted in an assessment center for performance in clinical practice (American Medical Association, Citation2015), as demonstrated by studies showing inconsistent correlations between competency test results and parameters of physician performance in actual practice (Rethans et al., Citation2002).

Twenty-three original studies that meet the eligibility criteria and report on results of original research are summarized in and detailed in the Appendix (). Three systematic literature reviews were also identified and summarized below.

One of the three systematic reviews (Jung et al., Citation2022) included meta-analysis of 10 retrospective cohort studies of postoperative outcomes with significantly heterogeneous results. Postoperative mortality among patients of older surgeons (older than 50, 55 or 60 years in different studies) was 14% higher compared to patients of middle-aged surgeons and 23% higher compared to patients of young-aged surgeons (younger than 40–45 years in most studies), though the latter difference was not statistically significant. Postoperative major morbidity among patients did not differ across surgeon age groups. Morbidity after minor (small organ) or major (large organ) surgeries also did not differ by age group.

Another systematic review (Choudhry et al., Citation2005) included 59 studies on the relationships between physicians’ age or years in practice and their medical knowledge, guideline adherence, patient mortality, and other quality of care outcomes. These studies, reporting on 62 groups of outcomes, were classified into six groups based on the observed association. A decline in performance for all assessed outcomes with increasing physician age or years in practice was reported in 32 of 62 evaluations (52%); heterogeneous results (only some showing decline) were reported in 13 evaluation (21%); 2 studies (3%) reported an initial increase in performance with growing experience, a peak, and a subsequent decline; 13 (21%) reported no association; one study (2%) reported improved performance for some outcomes but not for others, and one reported improved performance with age for all outcomes assessed. These results did not change substantially when analyses were restricted to objective outcome measures (use of chart audits or administrative databases vs. self-reports) or to studies adjusted for other known predictors of health care quality, such as patient comorbidity, physician volume or specialization. Although this review was based on heterogeneous studies, the results suggest that older physicians may be at risk for providing lower-quality care (Choudhry et al., Citation2005).

Studies reviewed by Eva (Citation2002) indicated that analytic capabilities declined with age, whereas nonanalytic processing remained intact and became increasingly dominant. Older physicians tended to rely more on their prior experience and to a lesser extent critically incorporated novel conflicting information. When facing a new case, older physicians were more influenced by information encountered earlier in the case. While experienced physicians may have more accurate first impressions, a failure to engage analytic processing in the decision-making process may result in medical errors. This review noted strong inter-individual differences that tended to increase with age. Although, on average, the performance of older physicians tended to be inferior, many older physicians performed at or above the level of their younger colleagues (Eva, Citation2002).

Although cognitive aging is a risk factor for deficits in physicians’ clinical practice, it should not be interpreted in isolation (Medical Board of Australia, Citation2017). Older physicians’ training occurred decades in the past and may not be updated regularly (Choudhry et al., Citation2005). For example, Day et al. (Citation1988) demonstrated that, on recertification examinations, older physicians who were further out of training, performed less well compared to more recently trained physicians on items related to new or changing knowledge; at the same time, they performed as well as younger examinees on items testing stable knowledge. Choudhry et al. (Citation2005) noted that older physicians may be less accepting to practice innovations.

Physician performance may be influenced by individual characteristics (such as medical school and certification status), organisational factors (for example, solo practice, support systems, hours worked, practice volume, appointment lengths), and systems level factors (such as community size and physician-to-population ratio) (American Medical Association, Citation2015; Kain et al., Citation2019; Wenghofer et al., Citation2009). Aging physicians who collaborate with their colleagues, engage in evidence-based discussions, receive performance feedback, and who use computerized reminder systems, may have advantage over those who practice in isolation or in more traditional settings (Choudhry et al., Citation2005).

Patient factors, such as disease acuity and complexity, should also be taken into consideration (American Medical Association, Citation2015). Samuels and Ropper (Citation2005), for instance, suggested that older doctors might tend to treat older and sicker patients.

Age-related physiological changes, such as reductions in manual dexterity, hearing, and visual acuity, may affect physician clinical competence and performance (American Medical Association, Citation2015; Moutier et al., Citation2013). Although intact cognition is important for optimal performance of surgeons, good eyesight and hand dexterity are also essential (Fortunato & Menkes, Citation2019; Yule et al., Citation2006).

Lack of valid tools for measuring physician competence or practice performance, and the variable nature of physician practices, are among the challenges faced when assessing practicing physicians (American Medical Association, Citation2015). Quality of care in one domain may not predict quality of care in another. Therefore, caution is recommended when interpreting results of physician assessments based on narrow measures of performance (Parkerton et al., Citation2003; Yen & Thakkar, Citation2019). Parkerton et al. (Citation2003) assessed primary care physicians on four measures of performance and found that most physicians (57.4%) ranked in the highest tertile for at least one measure and in the lowest tertile for at least one other measure.

Reported improvements in outcomes for patients of older surgeons may be partly explained by self-selection of highly skilled surgeons to continue performing surgical procedures, whereas lower skilled surgeons may decide to quit clinical practice (Satkunasivam et al., Citation2020; Tsugawa et al., Citation2018). Also, volume and complexity of surgical cases may decrease with increasing surgeon age (Bieliauskas et al., Citation2008).

Postoperative mortality, as a measure of surgery outcome, is affected by technical quality of the operation and other aspects of care, including postoperative inpatient care (R. J. Campbell et al., Citation2019). Postoperative mortality is specialty-specific and of greater relevance in some surgical specialties than others (Maruthappu et al., Citation2014).

In summary, although many studies demonstrated age-related decline in physicians’ clinical performance or competence, other studies detected no relationship with age, and still others reported superior performance of older physicians compared to younger counterparts. Although cognitive aging is a risk factor for deficits in physicians’ clinical practice, numerous other factors may contribute to underperformance of older physicians.

What is the association between physician cognition and clinical performance?

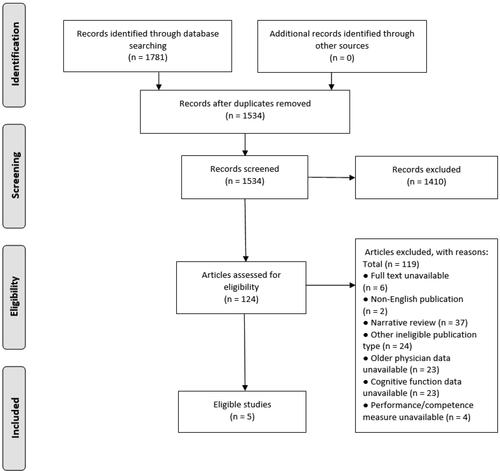

Studies relevant to this question include measures of both cognitive function and clinical performance or competence. A PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., Citation2009) detailing the study selection process is shown in .

Figure 2. PRISMA diagram for studies of a relationship between physician cognition and clinical performance or competence.

Five cross-sectional studies were identified in this review (). They demonstrate that, on average, cognitive functioning of physicians with problematic clinical performance or competence is inferior to that of physicians without such problems, or below the normative reference data. Turnbull et al. (Citation2006) found that a cognitive score was a strong predictor of performance in a standardized competency assessment test. Overall, these studies suggest that lower cognitive functioning may be a contributing factor to physician competence and performance problems.

Is there a cognitive threshold at which a physician is no longer fit to practice medicine?

Serra et al. (Citation2007) defined fitness for work as a capacity to work without risk to self or others. Physician fitness for practice (professionalism) includes multiple components, such as knowledge and skills, ethical aspects and values, effective relationships and communication with patients and colleagues, responsibility for their own health and well-being and that of their colleagues (General Medical Council (UK), Citation2021; Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, n.d.).

Del Bene and Brandt (Citation2020) sought to establish an approach to identify neuropsychologically impaired physicians. Seven cognitive and motor tests were administered, and nine key variables were derived. An impaired test score was defined as being below the 5th percentile of control physician performance. An impaired score on more than five of the nine cognitive and neuromotor variables was proposed as a cut-off to identify impaired physicians. Del Bene and Brandt (Citation2020) noted that, without a ‘gold standard’ for impairment, it was not possible to determine the perfect neuropsychological threshold; the threshold could differ for physicians in different specialties. The authors recommended additional research to develop specialty-specific neuropsychological criteria for impairment and noted that the cross-sectional retrospective design was a limitation of this study. To derive a useful predictor of cognitive impairment, a prospective longitudinal study of currently practicing physicians would be required (Del Bene & Brandt, Citation2020).

No prospective longitudinal data on cognitive functions in physicians over time, correlating them with clinical performance or competence, were identified for this review.

Overall, the literature to date provides no data to determine a firm cognitive cutoff for identifying physicians unfit to practice.

Other considerations regarding cognitive screening of older physicians

Considerations in support of cognitive screening

Physicians may not be good at assessing their own clinical performance and cognitive skills. For example, Davis et al. (Citation2006) systematically reviewed 17 studies conducted in the United Kingdom, Canada, United States, Australia, or New Zealand and comparing physician self-assessments with objective assessments of knowledge, skill, or performance. These studies included 20 comparisons between self- and external assessments, of which seven found agreement, whereas 13 demonstrated little, no, or even an inverse association between self-assessment measures and external indicators, suggesting a limited ability of physicians to accurately self-assess. Bieliauskas et al. (Citation2008) administered a battery of computerized neuropsychological tests to 359 older surgeons, of whom 294 surgeons also completed a self-report survey asking about perceived cognitive difficulties. It was found that there was no notable relationship between surgeon perception of cognitive difficulties and their performance on cognitive tests. Subjective cognitive problems were significantly related to surgeon retirement status or declared decision to retire in the next five years, whereas no notable relationship was seen between objective cognitive status and the declared retirement decision. These findings suggest that perceived cognitive decline, although it might not be an accurate reflection of true abilities, may play a role in a surgeon’s decision to retire (Bieliauskas et al., Citation2008).

Although it is their duty to report their own and their colleagues’ cognitive problems, physicians are generally reluctant to do so (Fortunato & Menkes, Citation2019). In a national survey among physicians in the United States (E. G. Campbell et al., Citation2007), 96% of respondents agreed that physicians should report significantly impaired or incompetent colleagues. However, 45% of physicians who had personal knowledge of an impaired or incompetent colleague indicated that at least once in the last three years they had not reported that colleague. Forty-six percent of physicians with personal knowledge of a serious medical error did not report that error in the last three years. In another national survey conducted in the United States (DesRoches et al., Citation2010), 64% of surveyed physicians agreed it was their duty to report impaired or incompetent colleagues. Of the 309 physicians who personally knew a colleague incompetent to practice, 105 (33%) did not report this colleague to the relevant authority. Weenink et al. (Citation2015) conducted a survey of legally regulated healthcare professions in the Netherlands: dentists, midwives, nurses, pharmacists, physicians, physiotherapists, psychologists, and psychotherapists. Although ∼31% of respondents had an experience with an impaired or incompetent colleague, only ∼69% acted upon this experience. The definition of action was broad and included talking to the colleague or discussing with other colleagues. Only one-fifth of participants reported the impaired/incompetent colleague to relevant authorities: the board of the organisation (11.7%), the professional association (3.0%) or the Health Care Inspectorate (6.0%) (Weenink et al., Citation2015).

Overall, evidence suggests that physicians may not be good at assessing their own clinical performance and cognitive skills and are generally reluctant to report impaired or incompetent colleagues.

Potential challenges with cognitive screening of physicians

Outcomes of most currently available cognitive assessment tools are difficult to interpret due to lack of normative data for physicians (Garrett et al., (Citation2021). The American Medical Association (Citation2015) (p. 7) stated:

… it is uncertain whether and how physician results should be compared to the general population and whether their results should be age-matched for interpretation purposes. … The nature of physician decisions, in terms of their difficulty, acuity and gravity, suggests that even minor changes in cognitive function may be impactful in patient care situations. … Results for cognitive testing that are interpreted as normal based on comparison to an age-matched, non-physician population could potentially represent a significant decline in highly intelligent individuals….

There are no standards on the level of cognitive decline at which a doctor is no longer fit to practice (Australian Medical Association, Citation2017; Lee & Weston, Citation2012; Medical Board of Australia, Citation2017). Prospective longitudinal studies correlating physician functioning in specific cognitive domains with key measures of clinical performance or competence in different medical fields would be needed to establish such standards in the face of normal cognitive aging. Such standards, however, would not necessarily apply to a physician compromised by a diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease or after having suffered a cerebral infarction. Lack of scientific evidence linking specific cognitive deficits with physician performance has been acknowledged by others (American Medical Association, Citation2015; Armstrong & Reynolds, Citation2020; Medical Board of Australia, Citation2017; Sataloff et al., Citation2020; Steffany, Citation2022).

Sets of neurocognitive abilities required for different medical specialties are diverse, reflecting the diversity of skills required and the level of responsibility that each specialty involves (Garrett et al., Citation2021; Gaudet & Del Bene, Citation2022). For instance, psychomotor impairment may weigh more heavily for surgeons, critical care, or emergency medicine specialists (Garrett et al., Citation2021); changes in processing speed may be particularly relevant for intensivists who rely on rapid decisions and responses (Skowronski & Peisah, Citation2012); visuospatial abilities are important for radiologists (Gaudet & Del Bene, Citation2022). Even if cognitive cut-off scores were available, these may differ by physician specialty area (Garrett et al., Citation2021; Gaudet & Del Bene, Citation2022; Katz, Citation2016; Saver, Citation2020). This in turn may require determination of appropriate assessments and tools, including development of new tests (Fortunato & Menkes, Citation2019).

Ethnic, cultural, and language factors may also affect performance on cognitive testing, especially for foreign-born physicians or international medical graduates, and must be considered to avoid inaccurate interpretation of test scores. For example, bilingual people are disadvantaged on verbal fluency tasks in their non-dominant language, and their lower-than-expected performance on such tasks may not be due to cognitive dysfunction but rather due to cultural or language differences (Gaudet & Del Bene, Citation2022).

Conclusion

This review provides some evidence suggesting that cognitive testing of late-career physicians may be useful. Physicians, despite their high education levels and careers that require constant and involved mental aptitude, are not immune to age-related changes in cognitive function. On average, cognitive abilities of physicians decline with increasing age, although this occurs about a decade later than in the general population. Physician competence and performance may also decline with age, though study results varied. Numerous factors, including measures of competence and performance, affect interpretation of results. Cognitive test scores are lower in physicians referred for assessment because of clinical performance or competence concerns than in control physicians with no such concerns, which suggests that lower cognitive functioning may contribute to physician performance problems. Cognitive functioning and clinical performance among older physicians are highly variable, and physicians may not be able to accurately self-assess. And yet, physicians were frequently reported to be reluctant to report their colleagues’ cognitive problems. So, some physicians may continue to practice despite a significant decline in the quality of the care they provide. For others, perceived cognitive decline, although it may not reflect true abilities, can accelerate their decision to retire.

The periods covered in some of the studies of physicians are 10 to 20 years old. Evidence from older studies should be considered cautiously, especially with changing specialities and demographics (AAMC, Citation2023), as well as struggles with meeting changing demands (Gupta et al., Citation2017).

Complex factors require contemplation in deciding to implement routine cognitive assessment of older physicians. Few cognitive assessment tools include normative data for physicians. The ability to competently practice medicine is driven by complex cognitive aptitudes that may vary across specialties, and specialty-specific cognitive assessments linked to impaired clinical performance are lacking. Evidence to date is not sufficient to comment on differing performance issues across medical specialties tied to cognitive functioning with age. No longitudinal studies were identified that would correlate cognitive function of physicians with their clinical performance, nor were there any that determined a level of cognitive decline that would be sufficient to render a physician unfit for practice. Cultural and language factors can also affect performance on cognitive testing, which need to be considered as many practicing physicians are graduates from international medical schools.

Beyond scientific evidence, implementation of routine cognitive screening to improve patient safety involves practical elements (e.g. valid and reliable cognitive assessment instruments for physicians), ethical considerations and legal factors (e.g. privacy and human rights concerns). These considerations were beyond the scope of the review.

Overall, the results of this review provide some support both for and against routine cognitive testing of older physicians, which will need to be carefully weighed by regulators, such as provincial Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons in Canada, in deciding whether to implement a policy requiring age-based cognitive assessment of physicians. Further research and investigation into the actual cognitive testing of older physicians and correlation to physician performance and patient outcomes is warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Natalie Jensen for help identifying relevant literature and for conducting environmental scans during the project.

Disclosure statement

The authors state that there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- AAMC. (2023). Physician specialty data report. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/physician-specialty-data-report

- American Medical Association. (2015). Council on medical education, Report 5: Competency and the aging physician. https://www.cppph.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/AMA-Council-on-Medical-Education-Aging-Physician-Report-2015.pdf

- Anderson, B. R., Wallace, A. S., Hill, K. D., Gulack, B. C., Matsouaka, R., Jacobs, J. P., Bacha, E. A., Glied, S. A., & Jacobs, M. L. (2017). Association of surgeon age and experience with congenital heart surgery outcomes. Circulation. Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 10(7), e003533.

- Anderson, G. M., Beers, M. H., & Kerluke, K. (1997). Auditing prescription practice using explicit criteria and computerized drug benefit claims data. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 3(4), 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2753.1997.t01-1-00005.x

- Armstrong, K. A., & Reynolds, E. E. (2020). Opportunities and challenges in valuing and evaluating aging physicians. JAMA, 323(2), 125–126. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.19706

- Australian Medical Association. (2017). National forum on reducing risk of suicide in the medical profession. Final Report. https://ama.com.au/sites/default/files/documents/DrHS_national_forum_final_report.pdf

- Bieliauskas, L. A., Langenecker, S., Graver, C., Lee, H. J., O’Neill, J., & Greenfield, L. J. (2008). Cognitive changes and retirement among senior surgeons (CCRASS): Results from the CCRASS Study. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 207(1), 69–78. discussion 78-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.01.022

- Boom-Saad, Z., Langenecker, S. A., Bieliauskas, L. A., Graver, C. J., O’Neill, J. R., Caveney, A. F., Greenfield, L. J., & Minter, R. M. (2008). Surgeons outperform normative controls on neuropsychologic tests, but age-related decay of skills persists. American Journal of Surgery, 195(2), 205–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.11.002

- Braak, H., Alafuzoff, I., Arzberger, T., Kretzschmar, H., & Del Tredici, K. (2006). Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathologica, 112(4), 389–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z

- Brown, E. C., Robicsek, A., Billings, L. K., Barrios, B., Konchak, C., Paramasivan, A. M., & Masi, C. M. (2016). Evaluating primary care physician performance in diabetes glucose control. American Journal of Medical Quality: The Official Journal of the American College of Medical Quality, 31(5), 392–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860615585138

- Campbell, E. G., Regan, S., Gruen, R. L., Ferris, T. G., Rao, S. R., Cleary, P. D., & Blumenthal, D. (2007). Professionalism in medicine: Results of a national survey of physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 147(11), 795–802. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-11-200712040-00012

- Campbell, R. J., El-Defrawy, S. R., Gill, S. S., Whitehead, M., Campbell, E. d L. P., Hooper, P. L., Bell, C. M., & Ten Hove, M. W. (2019). Association of cataract surgical outcomes with late surgeon career stages: A population-based cohort study. JAMA Ophthalmology, 137(1), 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.4886

- Cherbuin, N., Reglade-Meslin, C., Kumar, R., Jacomb, P., Easteal, S., Christensen, H., Sachdev, P., & Anstey, K. J. (2009). Risk factors of transition from normal cognition to mild cognitive disorder: The PATH through Life Study. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 28(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1159/000229025

- Choudhry, N. K., Fletcher, R. H., & Soumerai, S. B. (2005). Systematic review: The relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Annals of Internal Medicine, 142(4), 260–273. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-142-4-200502150-00008

- Cohen, R. A., Marsiske, M. M., & Smith, G. E. (2019). Chapter 10 - Neuropsychology of aging. In S. T. Dekosky & S. Asthana (Eds.), Handbook of clinical neurology (Vol. 167, pp. 149–180) Elsevier.

- Davis, D. A., Mazmanian, P. E., Fordis, M., Van Harrison, R., Thorpe, K. E., & Perrier, L. (2006). Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: A systematic review. JAMA, 296(9), 1094–1102. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.9.1094

- Day, S. C., Norcini, J. J., Webster, G. D., Viner, E. D., & Chirico, A. M. (1988). The effect of changes in medical knowledge on examination performance at the time of recertification. Research in Medical Education: Proceedings of the. Annual Conference. Conference on Research in Medical Education, 27, 139–144.

- Del Bene, V. A., & Brandt, J. (2020). Identifying neuropsychologically impaired physicians. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(2), 318–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2019.1666922

- Dellinger, E. P., Pellegrini, C. A., & Gallagher, T. H. (2017). The aging physician and the medical profession: A review. JAMA Surgery, 152(10), 967–971. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2342

- DesRoches, C. M., Rao, S. R., Fromson, J. A., Birnbaum, R. J., Iezzoni, L., Vogeli, C., & Campbell, E. G. (2010). Physicians’ perceptions, preparedness for reporting, and experiences related to impaired and incompetent colleagues. JAMA, 304(2), 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.921

- Drag, L. L., Bieliauskas, L. A., Langenecker, S. A., & Greenfield, L. J. (2010). Cognitive functioning, retirement status, and age: Results from the Cognitive Changes and Retirement among Senior Surgeons study. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 211(3), 303–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.05.022

- Eva, K. W. (2002). The aging physician: Changes in cognitive processing and their impact on medical practice. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 77(10 Suppl), S1–S6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200210001-00002

- Fortunato, J. T., & Menkes, D. L. (2019). The aging physician: A practical approach to protect our patients. Clinical Ethics, 14(1), 46–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477750919828163

- Garrett, K. D., Perry, W., Williams, B., Korinek, L., & Bazzo, D. E. J. (2021). Cognitive screening tools for late career physicians: A critical review. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 34(3), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988720924712

- Gaudet, C. E., & Del Bene, V. A. (2022). Neuropsychological assessment of the aging physician: A review & commentary. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 35(3), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/08919887211016063

- General Medical Council (UK). (2021, February). The meaning of fitness to practise. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/DC4591_The_meaning_of_fitness_to_practise_25416562.pdf

- Gershon, A. S., Hwee, J., Croxford, R., Aaron, S. D., & To, T. (2014). Patient and physician factors associated with pulmonary function testing for COPD: A population study. Chest, 145(2), 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-0790

- Glisky, E. L. (2007). Frontiers in neuroscience. Changes in cognitive function in human aging. In D. R. Riddle (Ed.), Brain aging: Models, Methods, And Mechanisms. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis.

- Goulet, F., Hudon, E., Gagnon, R., Gauvin, E., Lemire, F., & Arsenault, I. (2013). Effects of continuing professional development on clinical performance: Results of a study involving family practitioners in Quebec. Canadian Family Physician, 59(5), 518–525.

- Grace, E. S., Wenghofer, E. F., & Korinek, E. J. (2014). Predictors of physician performance on competence assessment: Findings from CPEP, the Center for Personalized Education for Physicians. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89(6), 912–919. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000248

- Gupta, D. M., Boland, R. J., Jr., & Aron, D. C. (2017). The physician’s experience of changing clinical practice: A struggle to unlearn. Implementation Science: IS, 12(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0555-2

- Institute of Medicine. (2015). Cognitive aging: Progress in understanding and opportunities for action. In D. G. Blazer, K. Yaffe, & C. T. Liverman (Eds.). The National Academies Press (US).

- Jung, Y., Kim, K., Choi, S. T., Kang, J. M., Cho, N. R., Ko, D. S., & Kim, Y. H. (2022). Association between surgeon age and postoperative complications/mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 11251. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15275-7

- Kain, N. A., Hodwitz, K., Yen, W., & Ashworth, N. (2019). Experiential knowledge of risk and support factors for physician performance in Canada: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 9(2), e023511. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023511

- Katz, J. D. (2016). The aging anesthesiologist. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology, 29(2), 206–211. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0000000000000299

- Korinek, L. L., Thompson, L. L., McRae, C., & Korinek, E. (2009). Do physicians referred for competency evaluations have underlying cognitive problems? Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 84(8), 1015–1021. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ad00a2

- Lee, L., & Weston, W. (2012). The aging physician. Can Fam Physician, 58(1), 17–18.

- Marco, C. A., Wahl, R. P., House, H. R., Goyal, D. G., Keim, S. M., Ma, O. J., Joldersma, K. B., Johnston, M. M., & Harvey, A. L. (2018). Physician age and performance on the American Board of Emergency Medicine ConCert Examination. Academic Emergency Medicine: Official Journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, 25(8), 891–900. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13420

- Markar, S. R., Mackenzie, H., Lagergren, P., & Lagergren, J. (2018). Surgeon age in relation to prognosis after esophageal cancer resection. Annals of Surgery, 268(1), 100–105. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002260

- Maruthappu, M., El-Harasis, M. A., Nagendran, M., Orgill, D. P., McCulloch, P., Duclos, A., & Carty, M. J. (2014). Systematic review of methodological quality of individual performance measurement in surgery. The British Journal of Surgery, 101(12), 1491–1498; discussion 1498. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9642

- Medical Board of Australia. (2017). Expert Advisory Group on revalidation. Final report. https://www.ranzcr.com/college/document-library/medical-board-report-final-report-of-the-expert-advisory-group-on-revalidation

- Mehrotra, A., Morris, M., Gourevitch, R. A., Carrell, D. S., Leffler, D. A., Rose, S., Greer, J. B., Crockett, S. D., Baer, A., & Schoen, R. E. (2018). Physician characteristics associated with higher adenoma detection rate. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 87(3), 778–786 e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2017.08.023

- Meier, R., Valeri, F., Senn, O., Rosemann, T., & Chmiel, C. (2020). Quality performance and associated factors in Swiss diabetes care – A cross-sectional study. PloS One, 15(5), e0232686. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232686

- Meltzer, A. J., Connolly, P. H., Schneider, D. B., & Sedrakyan, A. (2017). Impact of surgeon and hospital experience on outcomes of abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in New York State. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 66(3), 728–734 e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2016.12.115

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Moutier, C. Y., Bazzo, D. E. J., & Norcross, W. A. (2013). Approaching the Issue of the Aging Physician Population. Journal of Medical Regulation, 99(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.30770/2572-1852-99.1.10

- O’Neill, L., Lanska, D. J., & Hartz, A. (2000). Surgeon characteristics associated with mortality and morbidity following carotid endarterectomy. Neurology, 55(6), 773–781. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.55.6.773

- Parkerton, P. H., Smith, D. G., Belin, T. R., & Feldbau, G. A. (2003). Physician performance assessment: Nonequivalence of primary care measures. Medical Care, 41(9), 1034–1047. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLR.0000083745.83803.D6

- Pentzek, M., Abholz, H.-H., Ostapczuk, M., Altiner, A., Wollny, A., & Fuchs, A. (2009). Dementia knowledge among general practitioners: First results and psychometric properties of a new instrument. International Psychogeriatrics, 21(6), 1105–1115. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610209990500

- Perry, W., & Crean, R. D. (2005). A retrospective review of the neuropsychological test performance of physicians referred for medical infractions. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology : The Official Journal of the National Academy of Neuropsychologists, 20(2), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2004.04.002

- Poulin de Courval, L., Saroyan, A., Joseph, L., & Gauthier, S. (1996). [The competence of family physicians in caring for dementia patients. A survey of general practitioners in Quebec]. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 42, 1496–1502.

- Powell, D. H., & Whitla, D. K. (1994). Profiles in cognitive aging. Harvard University Press.

- Prystowsky, J. B. (2005). Are young surgeons competent to perform alimentary tract surgery? Archives of Surgery (Chicago, Ill.: 1960), 140(5), 495–500; discussion 500–502. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.140.5.495

- Reid, R. O., Friedberg, M. W., Adams, J. L., McGlynn, E. A., & Mehrotra, A. (2010). Associations between physician characteristics and quality of care. Archives of Internal Medicine, 170(16), 1442–1449. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.307

- Rethans, J.-J., Norcini, J. J., Barón-Maldonado, M., Blackmore, D., Jolly, B. C., LaDuca, T., Lew, S., Page, G. G., & Southgate, L. H. (2002). The relationship between competence and performance: Implications for assessing practice performance. Medical Education, 36(10), 901–909. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01316.x

- Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. (n.d). Professional. https://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/framework/canmeds-role-professional-e

- Samuels, M. A., & Ropper, A. H. (2005). Clinical experience and quality of health care. Annals of Internal Medicine, 143(1), 84; author reply 86-87; discussion 87. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-143-1-200507050-00015

- Sataloff, R. T., Hawkshaw, M., Kutinsky, J., & Maitz, E. A. (2020). The Aging Physician and Surgeon. Ear, Nose, & Throat Journal, 95(4–5), E35–E48

- Satkunasivam, R., Klaassen, Z., Ravi, B., Fok, K.-H., Menser, T., Kash, B., Miles, B. J., Bass, B., Detsky, A. S., & Wallis, C. J. D. (2020). Relation between surgeon age and postoperative outcomes: A population-based cohort study. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de L’Association Medicale Canadienne, 192(15), E385–E392. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.190820

- Saver, J. L. (2020). Best practices in assessing aging physicians for professional competency. JAMA, 323(2), 127–129. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.20249

- Serra, C., Rodriguez, M. C., Delclos, G. L., Plana, M., Gomez Lopez, L. I., & Benavides, F. G. (2007). Criteria and methods used for the assessment of fitness for work: A systematic review. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 64(5), 304–312. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2006.029397

- Skowronski, G. A., & Peisah, C. (2012). The greying intensivist: Ageing and medical practice – Everyone’s problem. The Medical Journal of Australia, 196(8), 505–507. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja11.11579

- Smith-Bindman, R., Chu, P., Miglioretti, D. L., Quale, C., Rosenberg, R. D., Cutter, G., Geller, B., Bacchetti, P., Sickles, E. A., & Kerlikowske, K. (2005). Physician predictors of mammographic accuracy. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 97(5), 358–367. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dji060

- Steffany, M. (2022). The challenge of competency assessment of the late-career practitioner. Journal of Healthcare Risk Management: The Journal of the American Society for Healthcare Risk Management, 41(3), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhrm.21492

- Stern, Y., Arenaza-Urquijo, E. M., Bartrés-Faz, D., Belleville, S., Cantilon, M., Chetelat, G., Ewers, M., Franzmeier, N., Kempermann, G., Kremen, W. S., Okonkwo, O., Scarmeas, N., Soldan, A., Udeh-Momoh, C., Valenzuela, M., Vemuri, P., & Vuoksimaa, E. (2020). Whitepaper: Defining and investigating cognitive reserve, brain reserve, and brain maintenance. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 16(9), 1305–1311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.07.219

- Tsugawa, Y., Jena, A. B., Orav, E. J., Blumenthal, D. M., Tsai, T. C., Mehtsun, W. T., & Jha, A. K. (2018). Age and sex of surgeons and mortality of older surgical patients: Observational study. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 361, k1343. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k1343

- Tsugawa, Y., Newhouse, J. P., Zaslavsky, A. M., Blumenthal, D. M., & Jena, A. B. (2017). Physician age and outcomes in elderly patients in hospital in the US: Observational study. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 357, j1797. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j1797

- Turnbull, J., Carbotte, R., Hanna, E., Norman, G., Cunnington, J., Ferguson, B., & Kaigas, T. (2000). Cognitive difficulty in physicians. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 75(2), 177–181. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200002000-00018

- Turnbull, J., Cunnington, J., Unsal, A., Norman, G., & Ferguson, B. (2006). Competence and cognitive difficulty in physicians: A follow-up study. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 81(10), 915–918. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000238194.55648.b2

- Waljee, J. F., Greenfield, L. J., Dimick, J. B., & Birkmeyer, J. D. (2006). Surgeon age and operative mortality in the United States. Annals of Surgery, 244(3), 353–362. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000234803.11991.6d

- Weenink, J. W., Westert, G. P., Schoonhoven, L., Wollersheim, H., & Kool, R. B. (2015). Am I my brother’s keeper? A survey of 10 healthcare professions in the Netherlands about experiences with impaired and incompetent colleagues. BMJ Quality & Safety, 24(1), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003068

- Wenghofer, E. F., Williams, A. P., & Klass, D. J. (2009). Factors affecting physician performance: Implications for performance improvement and governance. Healthcare Policy, 5(2), e141-160. https://doi.org/10.12927/hcpol.2013.21178

- Weycker, D. A., & Jensen, G. A. (2000). Medical malpractice among physicians: Who will be sued and who will pay? Health Care Management Science, 3(4), 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1019014028914

- Wilson, R. M., Harrison, B. T., Gibberd, R. W., & Hamilton, J. D. (1999). An analysis of the causes of adverse events from the Quality in Australian Health Care Study. The Medical Journal of Australia, 170(9), 411–415. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1999.tb127814.x

- Yen, W., & Thakkar, N. (2019). State of the science on risk and support factors to physician performance: A report from the pan-Canadian physician factors collaboration. Journal of Medical Regulation, 105(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.30770/2572-1852-105.1.6

- Yule, S., Flin, R., Paterson-Brown, S., & Maran, N. (2006). Non-technical skills for surgeons in the operating room: A review of the literature. Surgery, 139(2), 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2005.06.017

Appendix

Table A1. Medline search for literature on physician’s age as a determinant of cognitive functioning and clinical performance or competence.

Table A2. Medline search for literature on a possible cognitive threshold at which a physician is no longer fit to practice medicine.

Table A3. Summary of studies of the relationship between physicians’ age and their cognitive abilities.

Table A4. Summary of studies of the relationship between physicians age (or years in practice as a surrogate for age) and their competence/performance.