Abstract

Objectives

This paper explores the process of gaining consent from the perspectives of people living with dementia, their relatives/carers, and service providers. This is developed based on new primary qualitative research and addresses a gap in critical reflection on the practice and ethical process of research consent.

Methods

A qualitative approach was used to conduct this research through the implementation of four focus groups run with people living with dementia (n = 12), two focus groups with family members (n = 6), two focus groups with service staff (n = 5).

Results

Data was analysed thematically, to identify two core themes: consent as a journey and the flexible consent approach. These identified concerns with autonomy, decision making and placing people living with dementia at the centre of the consent process. The journey of consent emerged as central to supporting participation and enhancing the consent process.

Conclusion

The paper presents new evidence about the lived experience of research consent in the field of dementia, presenting the process of collecting consent in research as a flexible process that is best supported through a growing knowledge of participants and participation sites.

Introduction

Research is an important aspect of dementia service provision, supporting the care and treatment of people living with a diagnosis and supporting quality of life and wellbeing (Alzheimer’s Europe, Citation2019). While not all services may be able to conduct research or evaluation, it provides a valuable way to explore the impact and value of service provision and is often required by those funding or commissioning interventions (Tucker et al., Citation2023). An essential aspect of the research process is obtaining ethical approval (Guarino et al., Citation2016). The ethical process should be one which supports people to take part in research on an equal footing and can engage with those who are may be considered ‘vulnerable’ or underrepresented (Prosser et al., Citation2008; Alzheimer’s Europe, Citation2019, Thoft et al., Citation2021). Many ethical processes are based on clinical research and have little flexibility for different areas of research that may be more pragmatic, or community based. Planning how to gain informed consent from those participating, is one such area. Overwhelmingly researchers in this field use a formal, written consent form, which is often the default expectation for many institutional/organisational/professional ethics processes—although other variations are used such as video or audio recorded. Dementia researchers are increasingly committed to dementia-friendly practice, there has been surprisingly little critical reflection on the role of consent forms or discussion of alternatives.

The complex nature of consent may result in the exclusion of the person living with dementia (Schütz et al., Citation2016), before the study has even taken place. Informed consent is the process by which a potential research participant can review the risks and benefits of taking part and assess the value of the research for their own participation (Jongsma & van de Vathorst, Citation2015; Parmar, Citation2021). Chandra et al. (Citation2021) discuss the differences between informed consent and assent, whereby assent involves a lower level of understanding. Evans et al. (Citation2020) comment that the exclusion of people lacking capacity to consent can lead to a lack of research in later life conditions. However, this is a complex area, with definitions of assent challenging to agree on (Overton et al., Citation2013). While consent identifies that the participant is able to understand and recall information in order to agree to participate, assent is still considered to involve a form of choice and a level of understanding (Black et al., Citation2010). However, practically this is still an ambiguous area.

One of the most common difficulties individuals with dementia face is following long, complex information (Hake et al., Citation2017). Due to deterioration in memory, language and executive functioning as dementia progresses, individuals with dementia report losing track as they read (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2012). Long sentences, complex forms and vocabulary may be challenging to understand and may not be culturally relevant (Alzheimer’s Europe, Citation2019). One of the fundamental challenges in making research more accessible for people living with dementia is selecting the most appropriate consent form which is also approved by the Research Ethics Committee (Hegde & Ellajosyula, Citation2016), for Higher Education, organisational and professional committees nationally and internationally. Generic consent forms for research have been developed with small, compact, jargon laden text that is hard for people to understand and respond (Jayes & Palmer, Citation2014), and may result in participants signing forms without having read through or fully understood what is presented (Alzheimer’s Europe, Citation2019). Symptoms that are associated with dementia like difficulties with concentration, understanding, and short-term memory, makes their ability to provide informed consent questionable (Hegde & Ellajosyula, Citation2016). However, UK guidance, developed by people living with dementia, families and carers, states that people living with dementia have a right to take part in research and to be provided with information that is accessible (Dementia Action Alliance, Citation2010). Furthermore, Dementia Alliance International’s core value is that of ‘nothing about us without us’, emphasising the need for inclusion in all aspects of care and research (Dementia Alliance International, Citation2021). The Mental Capacity Act (Citation2005) in the UK states that people should be able to consent to participate and that information should be presented in a way that aids understanding to support this consent. This is also reflective of the principles set out by the United Nations (Citation1991) and by the World Health Organisation’s (Citation2004) guidance for establishing mental health care legislation, as well as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, Citation2006), which emphasises the need for people with disabilities to have the same rights as other people. The Alzheimer’s Europe report on research (Alzheimer’s Europe, Citation2019) reported that people living with a diagnosis of dementia should be enabled to provide their own consent, with adapted consent available for those who need it, e.g. via verbal means. The National Health Service’s Health Research Authority (Citation2019), as an example of one national institution that is also echoed in other countries, guidance on consent recommends that consent can be adapted to different groups and their needs. This is echoed by the Dementia Enquirers Research guide (2019) which states that consent forms can be modified in design if they contain certain key information on: understanding the research, personal data being collected, benefits and risks, withdrawal process and possibility to ask questions. While the adaptation of consent is included in the guidance, it is the experience of the authors that Research Ethics Committees tend to prefer a written format, an experience also noted in a reflective paper by Thoft et al. (Citation2021). The aim of this paper therefore focusses on the formal written consent process.

This paper explores the process of gaining consent from the perspectives of people with dementia, their relatives/carers, and service providers. This is developed based on new primary qualitative research and addresses the major gap in practice/ethical process identified above. This provides a new approach to consent literature and places the experiences of those giving and gaining consent central to the discussions. The study was initiated following feedback from a dementia service in the East Midlands, UK. Having taken part in a research study with one of the authors, they reported that the consent forms had been very challenging, and that many of their members had found this a demanding process to go through, more so than the actual research. This is something that the research team had previously heard anecdotally. The aim of this paper is therefore to present new evidence-based guidance grounded on the lived experience of consent in social and community settings and how these pose important challenges for normative processes, and what this could provide in terms of learning to develop more user-friendly approaches.

Methods and aim

The research aimed to understand whether those living with dementia understand the language used when seeking consent; whether it is appropriate; whether the style and format of the consent form aids understanding, and whether the consent form covers sufficient relevant information for the potential participants to give informed consent. This paper covers the outcomes of the consent process as experienced by the participants in this study. This paper provides findings from the views and experiences of gaining or seeking consent from people living with dementia, family members/carers, and service leads.

Data collection

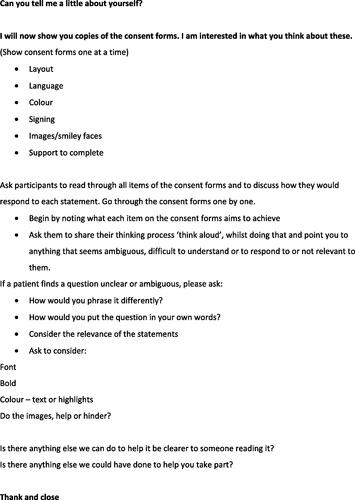

In consultation with people living with dementia, carers/relatives and a service provider, focus groups were selected as our data collection method. Focus groups were considered to enable the development of a supportive environment for participation. Given the focus of the research was the rather abstract topic of consent, our consultation group, who all had dementia, said they would be more comfortable with the support of peers when participating. Forchuk et al. (Citation2015) found that focus groups can enhance a sense of peer support and engagement in research. A copy of the discussion guide is included as .

Participants with dementia, service delivery staff and family members were recruited from a local community dementia service in the East Midlands, UK. People living with dementia were also recruited from a young onset dementia public and patient involvement and engagement group who meet virtually and have representation from across England. The people living with dementia were all living in their own homes alone or with relatives. They all consented independently to participate, however, some were supported by a trusted advocate, such as their family member or a dementia service lead. All the participants (staff, family and those with dementia) had previous experience of being part of a research study and therefore had knowledge of the processes and concepts being discussed.

The findings here are drawn from analysis of eight focus groups (4 with people living with dementia, speaking with 12 individuals; 2 with family members, speaking with 6 individuals; 2 with dementia service staff, speaking with 5 staff). The groups were undertaken face-to-face and virtually depending on the group (see for a full breakdown). The focus groups for the people living with dementia averaged 44 min (23–76 mins); for family and carers they averaged 25 min (23–27mins) and the service staff interviews averaged 21 min (17–24mins).

Table 1. Focus group attendance.

A discussion guide was developed to explore the experiences of collecting consent in research. This explored the use of consent forms (design and language) and the process of gaining consent at the start of the research process. Two consent form examples were used as part of the discussions to give context and explore different ways of designing a form. The discussion guide allowed participants to give spontaneous responses and information about the content and understanding of research terms, for example risks and benefits, anonymised data and confidentiality. All the focus groups were audio recorded digitally with the permission from the participants. These recordings were then transcribed by the researcher team verbatim.

Ethics

The project received ethical approval from the University of Northampton’s Faculty of Health, Education and Society Research Ethics Committee (REF: FHSRECHEA000277). All participants were informed about the study prior to participation, and members of the team attended meetings with participants with dementia and families to discuss the project beforehand. Participants with dementia provided recorded verbal consent, and all other participants provided written consent.

Analysis

A thematic analysis was undertaken based on Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) six stages of thematic data analysis. This was undertaken by two experienced qualitative senior researchers who went through a process of familiarisation by reading all the transcripts. Initial codes were then generated with both researchers reviewing these to identify and name the key themes.

Results

Participants shared a range of significant and practical dilemmas in the consent process with people living with dementia. These centred on issues of autonomy, decision-making and the need to place people living with dementia at the heart of a consent process which is flexible enough to reflect diversity.

Consent as a journey

The importance of attending to consent as a journey or process was a central tenant of the views offered by participants. Their contributions also illustrated the need to ensure that consent was not planned as a single time point or even a linear process of delivery, but rather offered flexibility. This flexibility was key to ensuring an effective response to the diverse range of needs and wishes that people living with dementia have.

Within ethically constituted research, the needs and wishes of participants are paramount. People living with dementia in this study offered two perspectives on this; some advocated the need for their autonomy of decision making to be reflected in the design of consent processes and their right to be involved.

…as a researcher taking consent you’ve got to be really careful that you don’t just simply talk to the supporter and take their consent. You need to actually find ways of getting the person to understand what it is and whether they want to do it.

Steve, person living with dementia, Focus Group 3

Well, I think so I think one ought to be able to say at any stage in any sort of program that involves my future I prefer to say definitely this is okay, this is okay and this is not okay…

Anne, person living with dementia, Focus Group 1

Alongside this came a recognition for some that as their dementia progressed the support of others may be needed. Some said it was important to share their views with others before this happened, in order that those around them would know their wishes ahead of time.

…the person who is the supporter must know me, must know about me, know any preferences I expressed while I was able to if I’m not able to now…

Steve, person living with dementia, Focus Group 3

For me at my stage no but I think for people further down the line or struggling to understand their carer would be essential.

Fiona, person living with dementia, Focus Group 3

Other participants intimated a hesitancy to be approached in isolation from their relatives or carers. They argued that novel situations, documentation, processes, and people can act as precursors to increased anxiety and enhance an existing lack of confidence. This further highlights the need for flexibility and considerable preparation in designing the consent journey with adaptations made according to the needs shared by recruiting organisations prior to engagement.

At the moment I’m happy. If my dementia gets any worse, will I feel anxiety, trepidation, big word!

Chris, person living with dementia, Focus Group 4

…but I live with my family so this depends what they think.

Sue, person living with dementia, Focus Group 2

Carers and service providers also signalled a need to ensure the consent journey was planned to reduce the level of new information/situations people living with dementia were exposed to at any given point. New information coupled with a perceived lack of confidence, meant that some preferred their relatives to take a lead on decision making, and some service representatives suggested that the recording of a consent process could be undertaken by individuals already known to people living with dementia, under the direction of research teams.

In the past if I’ve not been around he’d [husband] have done it himself so it’s a change and I can see the difference there and now anything that requires some brain power just gets passed over instantly.

Pat, relative, Focus Group 6

Don’t expect to get any kind of sensible answer if you don’t know them. They’ve got a very high level of anxiety and a low level of confidence. They know that they’re likely to not understand or be confused about things. So, they’re already ready for that as soon as somebody new comes in and it’s almost a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Lesley, dementia service representative, Focus Group 7

Flexible consent approach

Flexibility in the consent process was a key theme in the contributions of the participants. A combination of ways of communicating information—adding flexibility to the process - was also considered imperative. Examples included written and verbal (where the focus of a study was deemed low risk), independent and collaborative consent capture/recording.

There needs to be a combination of ways to consent and not just one form because if it gets too wordy I don’t read it. It’s got to be to the point and not too much unnecessary words. …have difficulty with reading and text and visual stuff I think it would be good quite good to have a vocal thing where even if it’s a complicated thing but somebody has a 1-2-1 where you’re asked questions and somebody else can fill it in.

Sam, person living with dementia, Focus Group 4

The need for flexibility in recruitment on the part of research teams is key, including the ability to adapt plans at short notice. A recognition that researchers may not be welcomed by some potential participants and may need to change their approach was considered important.

…ultimately if someone who’d actually come to the session and then they were particularly offended about you [researcher] being there it would be up to the researchers to leave rather than them… So, they know they’re there in the background as invited guests and if they become unwelcome guests at any point then it’s their responsibility to leave.

Greg, dementia service representative, Focus Group 8

Where researchers work with carers/relatives and service providers, they can design flexible approaches that draw on the previous experiences of families, building familiarity with their presence and role over time. This also ensures that where partial or segmented recall of the consent journey occurs there are individuals able to reassure and discuss concerns. This was particularly raised in relation to signing consent forms, which can cause anxiety later and was related to a formal, contractual or financial process and lending the process gravitas.

I’m thinking about my Mum, that causes confusion [signing a form] and then post that causes massive anxiety. She forgets she’s filled it in and then she goes oh there’s some paperwork, what have I done, what have I filled in, what have I signed away

Phil, relative, Focus Group 5

…she might recall that she signed something but she wouldn’t be able to tell you what it’s for.

Rich, relative, Focus Group 5

Fluctuating capacity and willingness to participate were also key concerns of all participant groups. Changing capacity between multiple sessions, short term memory within the timespan of documenting consent for a project, and changes in mood and willingness to take part were all noted as reasons for flexibility in the consent journey.

…you would have to state every time you came the purpose as [people living with dementia] wouldn’t remember one week from the next.

Carol, dementia service representative, Focus Group 8

I can imagine myself having to explain that straight away and then I might have lost them for the rest of it, do you know what I mean?

Lesley, Dementia service representative, Focus Group 7

Representatives from the dementia settings reported that researchers should become familiar with settings they work in or where they recruit potential participants. As such building rapport with participants is also about building rapport with the organisations (where relevant) and understanding the usual practice in which the consent process may be slotted into. For example, when visiting settings to get to know participants, visiting on days when the group usually meet. The role of the researcher is then about being flexible to the needs of the organisations they may be working with as well as the individual participant’s needs.

Some of the participants living with dementia queried the extent to which researchers had the power to affect recommendations about consent in practice. They had experienced the inflexibility of the research process, and shared concerns regarding the role of research ethics committees (RECs) in the rigidity of their requirements. The thoughts of people living with dementia on this topic are an important contextual concern for the findings reported above and the potential limitations researchers have in being flexible in their approach.

I’m going to sound kind of rude again and in a way we’re talking to the wrong people, not you but we are talking to the wrong people because as far as I know your hands are tied because the funders and the Ethics Committee decide how you get consent and then you just present that consent so none of us get a say in it until we change their opinion.

Lynn, person living with dementia, Focus Group 4

…we were going to be funded by [funding organisation] to carry out a research project but when trying to develop our idea further and finding out as we went into the ethics side of things how impossible to match their requirements with people with dementia and we’ve thought we’re not up to this.

Chris, person living with dementia, Focus Group 4

Discussion

The aim of the project was to explore the experiences of gaining and giving consent for people living with dementia in research, enabling the development of user-friendly approaches. The findings from this study add critical new evidence to existing literature on the lived experiences of consent for people living with dementia, carers and service providers themselves. This emphasises the importance of the research relationships, the need for flexibility and anonymity, rather than a focus only on using an adapted consent form. This includes planning consent as an ongoing journey and not something that is made at a single time point or initial contact (Alzheimer’s Europe, Citation2019; Dewing, Citation2007).

This paper also reiterates the need for flexibility and finding a balance of enabling autonomy of decision-making where this meets the needs of the participants and that these needs will have variability between individuals (Mueller et al., Citation2017). This could also reflect the need for flexibility within individual’s who experience fluctuating capacity, as is shown in the findings above. Additionally, there is a need to recognise that some people living with dementia will prefer to make decision independently, while others may prefer involvement of carers or professionals in supporting consent-related decisions. The needs of different participant groups also need consideration here, as those from a minority ethnic background may prefer to have input from family members in making decisions (Alzheimer’s Europe, Citation2019). Part of supporting autonomy is the provision of clear and comprehensive information that clearly sets out the particulars of the research and aid in decision making (DEEP, Citation2019; Thoft et al. Citation2021; Wolverson et al., Citation2023), and through training for carers or services in providing support that can enhance understanding (Haberstroh et al., Citation2014; Mueller et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, enhanced consent processes, such as simplified forms or different presentations of consent (verbal, slideshow), can provide greater understanding and support participation (Mittal et al., Citation2007). A review of audio-visual approaches to consent did not find these raised the level of understanding and participation for research but did suggest the process of consent was more satisfactory and that further research was needed to explore innovations in gaining informed consent (Synnot et al., Citation2014).

There is little literature or research that explores the use of enhanced consent processes (Poth et al., Citation2023). These, Poth et al. (Citation2023) argue focus on supporting a person’s understanding of the research and do not attempt to support the three other core elements of gauging consent, i.e. appreciation, reasoning, and expression of a choice (p.293). Aspects that may support informed consent go beyond the use of forms and/or audio-visual elements and should include careful assessment of verbal and nonverbal language. An overreliance on memory and attention have also been identified as impacting on a person with dementia’s ability to provide consent (Haberstroh et al., Citation2014; Mueller et al., Citation2017). The use of visuals, adaptations in communication and use of keywords can have a positive impact (Mueller et al., Citation2017; Poth et al., Citation2023). However, a strengths-based approach by Poth et al. (Citation2023) did not find any significant results when comparing an enhanced consent process to a standard consent process, although again understanding may have been improved. What this present paper explores is that consent is a process that requires consideration beyond the act of gaining consent, where getting to know individuals and settings, using enhanced consent forms, understanding the balance of autonomy in decision-making, and researcher flexibility are key to ensuring that people living with dementia and those around them are heard in the consent process. These aspects also ensure that people are not excluded from participation. Additionally, research teams need to be empowered to be flexible enough to meet the needs and wishes of those they are recruiting.

Liaising with those who know potential participants (service providers, relatives and carers) whilst planning the consent journey was considered an important component. This is reflected in the approach by Dewing (Citation2007) who advocates for person-centred research relationships in the consent process. This means considering the broad range of needs, situation and setting that any context may include. Holden et al. (Citation2018) paper explores the way that people living with dementia can consent to research and acute care when they are in the more advanced stages of their dementia. Their paper, however, focuses on the procedural element of gaining consent and is based on process mapping and engagement with institutional review boards. What this present paper identifies is the need for a relational approach to sit alongside the procedural, as identified from the perspective of those living with a diagnosis of dementia. Alongside this is a need for dementia researchers to plan for flexibility of approach in relation to introductions, sharing information, recording decisions and capturing ongoing capacity and consent. Papers which illustrate the challenges that researchers face in balancing the consent process in dementia focussed research are useful in informing the wider community of how reflective practice within research teams can offer practical guidelines for meeting this challenge (Slaughter et al., Citation2007). However, there is a need for broader research communities to reflect on the needs of participants and research teams in these situations, working to empower a flexible approach which embeds the changing needs, wishes and roles of different stakeholders in the consent process. An example of such a collaboration is documented in Russell et al. (Citation2023) paper, discussing the role of interdisciplinary approaches to address ways of supporting those underrepresented in research to participate through ethical and methodological review. Participants in this study were acutely aware of restrictions in the design of research documentation and processes arising from the expectations of those who approve research, and that this can impact on their ability to participate. Therefore, finding ways to as a community to address these challenges is central to ensuring more people can participate.

People living with dementia may wish to share their preferences in relation to research with others so that they can make decisions on their behalf when they are no longer able to. The emphasis here is on others knowing what this individual would prefer so that they are acting on their best interests. Carers also shared concerns that people living with dementia may not always recall or understand that they are taking part in research and that this can change from one day to the next, therefore having an understanding of the person’s wishes may be crucial to their continuation in the research. This was a major finding in Evans et al. (Citation2020) review of consent processes, identifying what a person wishes while they have capacity to decide is important so that future decisions are enacted in accordance with these wishes, with advance directives being one way to support such choices. There is potential for such considerations to be made regarding advance directives for future research participation. This exists in medical models, for example with people deciding on end-of-life treatment, whether to leave their brains to medical research or organs for donation (Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2016). This raises the potential for such decisions to be made in relation to social research. Furthermore, the participants acknowledged that consent processes and forms remain the same regardless of the ‘level’ of study. The recommendation was to explore different processes that could be more flexible depending on the type of study. There is a difference from a person being involved in invasive medical research to taking part in an evaluation of a service and completing similar complex consent forms.

In the UK, legislation states that as capacity changes or is gradually lost, decisions on care or research involvement fall to advance directives or proxy consent, alongside capacity assessments (MCA, Citation2005). This is also reflective of the United Nations (Citation1991) principles on mental health care. Findings from Overton et al. (Citation2013) research on how proxy decisions were made for people living with dementia who no longer had capacity revealed that advance directives were not always followed, with those making the decisions considering the values and beliefs they felt related to the individual in question, in that moment as opposed to when the directives had been established. This was particularly true when a person had decided not to take part in research. Decisions made by participants in Overton et al.’s study reported to have based their decisions on verbal and nonverbal signs or emotional responses. Overton et al. consider there is a high degree of trust placed in the relationship between a person with dementia and their formal/informal caregivers. This is reflected by several of the participants in this present study who wanted the support of their family when considering whether to participate in research or not, a trust that in this instance was also imparted to the dementia service they attended. This remains a complex area where further research and potentially training for caregivers can support a greater emphasis on supporting decisions made by those who are living with dementia.

One aspect that was raised by all of the participants was the need to reduce new information or situations in research. This relates to the newness of researchers in a setting or meeting potential participants. Recommendations for researchers to meet participants in advance of collecting data were made, to discuss research topics and to familiarise themselves with setting practices and individuals. This was considered to be a two-way process that would support people living with dementia to take part in research. While this is perhaps a practice to strive for, it is also acknowledged that this can take time and resources that many research projects may not have. Suggestions were also made for a greater collaboration with services to support the consent process, under research direction.

Limitations

This research has added critical new perspectives from people living with dementia, relatives/carers and service representatives. Given the challenges of working to meet their diverse needs, we recognise that some of the recommendations highlighted may not be feasible within a larger scale study, however we offer them as a basis for broader discussions about the ways in which flexibility can be built into research studies that focus on participants drawn from what might be termed lesser heard groups. This paper has not covered capacity assessments and while the authors recognise that this is a central aspect of consent, the purpose of the paper was to explore the experience of gaining consent from a range of perspectives.

It should be noted that the research is ongoing and phase 2 will capture the views of Research Ethics Committee members through a national questionnaire designed to gain an understanding of how an ethics committee may respond to a newly designed dementia friendly consent form and recommendations for practice in the field when offering approval for consent processes in research. The authors also acknowledge the limitations of using a focus group approach. Such limitations may include the dominance of one member, potential for conflict or dissenting views to be stunted, and the group may have a bias (Smithson, Citation2000). The authors facilitation of the groups aimed to mitigate these limitations, although they may still have impacted on the findings of the research.

Conclusions and implications for practice

This research has discussed the views of people living with dementia, carers/relatives and service providers on informed consent in research, providing a current contribution to this complex area of dementia study. The dissemination and discussion of these findings to/with approval giving and funding organisations is also of paramount importance in empowering researchers and other stakeholders in dementia focused research to apply them with flexibility in practice, carry out projects which meet the needs of the broadest range of participants. This research has broader ramifications for a range of vulnerable groups in the UK and internationally who may present with a diversity of needs and where flexibility is key to ensuring ethical consent practices: researchers working in the field who can build knowledge of each participants’ needs would benefit from being able to tailor their approach to the consent journey accordingly. A broader re-consideration of the ways in which RECs and the broader dementia research community can encourage and empower researchers to embed flexibility in the consent journey is needed.

The authors are aware of areas of research and conversations taking place on the issue of consent and challenges of meeting ethical processes in research practice. There is a need for an international agenda to drive forward a conversation on inclusive consent processes. This would provide an opportunity to share best practice approaches and enhance international critical discussions on inclusive consent in research, whilst balancing the legal and ethical requirements of research against the diverse needs of (potential) research participants for whom consent processes can preclude participation.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper would like to acknowledge and thank the participants and recruiting organisations for this study, who gave their time and expertise so generously.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to ethical/commercial issues, data underpinning this publication cannot be made openly available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alzheimer’s Association (2016). End-of-life decisions honoring the wishes of a person with Alzheimer’s Disease. https://www.alz.org/national/documents/brochure_endoflifedecisions.pdf

- Alzheimer’s Europe. (2019). Overcoming ethical challenges affecting the involvement of people with dementia in research: Recognising diversity and promoting inclusive research. (ISBN 978-2-9199578-0-4).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2012). Australia’s health 2012. (Australia’s Health Series no.13. Cat. no. AUS 156). AIHW.

- Black, B. S., Rabins, P. V., Sugarman, J., & Karlawish, J. H. (2010). Seeking assent and respecting dissent in dementia research. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(1), 77–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181bd1de2

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Chandra, M., Harbishettar, V., Sawhney, H., & Amanullah, S. (2021). Ethical issues in dementia research. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 43(5 Suppl), S25–S30. https://doi.org/10.1177/02537176211022224

- Dementia Action Alliance. (2010). The Dementia Statements. [online]. https://www.dementiaaction.org.uk/nationaldementiadeclaration

- Dementia Alliance International. (2021). Our Core Beliefs. [online]. https://dementiaallianceinternational.org/about/our-core-beliefs

- Dewing, J. (2007). Participatory research: A method for process consent with persons who have dementia. Dementia, 6(1), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301207075625

- Evans, C. J., Yorganci, E., Lewis, P., Koffman, J., Stone, K., Tunnard, I., Wee, B., Bernal, W., Hotopf, M., & Higginson, I. L, MORECare_Capacity. (2020). Processes of consent in research for adults with impaired mental capacity nearing the end of life: Systematic review and transparent expert consultation (MORECare_Capacity statement). BMC Medicine, 18(1), 221. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01654-2

- Forchuk, C., Meier, A., Montgomery, P., & Rudnick, P. (2015). Peer support as a direct benefit of focus group research: Findings from a secondary analysis. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, 19(1), 88–100. https://doi.org/10.37200/V19I1/8140

- Guarino, P. D., Vertrees, J. E., Asthana, S., Sano, M., Llorente, M. D., Pallaki, M., Love, S., Schellenberg, G. D., & Dysken, M. W. (2016). Measuring informed consent capacity in an Alzheimer’s disease clinical trial. Alzheimer’s & Dementia (New York, N. Y.), 2(4), 258–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trci.2016.09.001

- Haberstroh, J., Müller, T., Knebel, M., Kaspar, R., Oswald, F., & Pantel, J. (2014). Can the mini-mental state examination predict capacity to consent to treatment? GeroPsych, 27(4), 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1024/1662-9647/a000113

- Hake, A. M., Dacks, P. A., & Arnerić, S. P, CAMD ICF working group. (2017). Concise informed consent to increase data and biospecimen access may accelerate innovative Alzheimer’s disease treatments. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 3(4), 536–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trci.2017.08.003

- Health Research Authority. (2019). Informing participants and seeking consent. https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/best-practice/informing-participants-and-seeking-consent/

- Hegde, S., & Ellajosyula, R. (2016). Capacity issues and decision-making in dementia. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 19(Suppl 1), S34–S39. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-2327.192890

- Holden, T. R., Keller, S., Kim, A., Gehring, M., Schmitz, E., Hermann, C., Gilmore-Bykovskyi, A., & Kind, A. J. H. (2018). Procedural framework to facilitate hospital-based informed consent for dementia research. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(12), 2243–2248. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15525

- Jayes, M., & Palmer, R. (2014). Initial evaluation of the consent support tool: A structured procedure to facilitate the inclusion and engagement of people with aphasia in the informed consent process. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(2), 159–168. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2013.795999

- Jongsma, K. R., & van de Vathorst, S. (2015). Dementia research and advance consent: It is not about critical interests. Journal of Medical Ethics, 41(8), 708–709. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2014-102445

- Mittal, D., Palmer, B. W., Dunn, L. B., Landes, R., Ghormley, C., Beck, C., Golshan, S., Blevins, D., & Jeste, D. V. (2007). Comparison of two enhanced consent procedures for patients with mild Alzheimer Disease or mild cognitive impairment. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry : official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(2), 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e31802dd379

- Mental Capacity Act. (2005). Mental Capacity Act 2005. HMSO. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/contents

- Mueller, T., Haberstroh, J., Knebel, M., Oswald, F., Kaspar, R., Kemper, C., Halder-Sinn, P., Schroeder, J., & Pantel, J. (2017). Assessing capacity to consent to treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors in dementia using a specific and standardized version of the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool (MacCAT-T). International Psychogeriatrics, 29(2), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104161021600154X

- Overton, E., Appelbaum, P. S., Fisher, S. R., Dohan, D., Roberts, L. W., & Dunn, L. B. (2013). Alternative decision-makers’ perspectives on assent and dissent for dementia research. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(4), 346–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.027

- Parmar, D. (2021). Ethical aspects of informed consent in dementia. Global Bioethics Enquiry Journal, 9(1), 42–45. https://doi.org/10.38020/GBE.9.1.2021.42-45

- Prosser, J., Clark, A., & Wiles, R. (2008). Realities working papers: Visual research ethics at the crossroads. Economic and Social Research Centre National Centre for Research Methods.

- Poth, A., Penger, S., Knebel, M., Müller, T., Pantel, J., Oswald, F., & Haberstroh, J. (2023). Empowering patients with dementia to make legally effective decisions: A randomized controlled trial on enhancing capacity to consent to treatment. Aging & Mental Health, 27(2), 292–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.2024797

- Russell, A. M., Shepherd, V., Woolfall, K., Young, B., Gillies, K., Volkmer, A., Jayes, M., Huxtable, R., Perkins, A., Noor, N. M., Nickolls, B., & Wade, J. (2023). Complex and alternate consent pathways in clinical trials: Methodological and ethical challenges encountered by underserved groups and a call to action. Trials, 24(1), 151. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-023-07159-6

- Schütz, H., Heinrichs, B., Fuchs, M., & Bauer, A. (2016). Informierte einwilligung in der demenzforschung. eine qualitative studie zum informationsverständnis von probanden. Ethik in Der Medizin, 28(2), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00481-015-0359-3

- Slaughter, S., Cole, D., Jennings, E., & Reimer, M. (2007). Consent and assent to participate in research from people with dementia. Nursing Ethics, 14(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733007071355

- Smithson, J. (2000). Using and analysing focus groups: Limitations and possibilities. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 3(2), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/136455700405172

- Synnot, A., Ryan, R., Prictor, M., Fetherstonhaugh, D., & Parker, B. (2014). Audio-visual presentation of information for informed consent for participation in clinical trials. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2014(5), CD003717. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003717

- Thoft, D. S., Ward, A., & Youell, J. (2021). Journey of ethics – Conducting collaborative research with people with dementia. Dementia (London, England), 20(3), 1005–1024. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301220919887

- Tucker, R., Vickers, R., Adams, E., Burgon, C., Lock, J., Goldberg, S., Gladman, J., Masud, T., Orton, E., Timmons, S., & Harwood, R. H. (2023). Factors influencing the commissioning and implementation of health and social care interventions for people with dementia: Commissioner and stakeholder perspectives. MedRxiv the Preprint Service for Health Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.26.23287750

- United Nations. (1991). Resolution 46/119 Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness and the Improvement of Mental Health Care. United Nations General Assembly.

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). [online]. https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd

- The UK Network of Dementia Voices (DEEP). (2019). Dementia Enquirers research pack. Carrying out your research project Simple guidance and ideas for DEEP groups. https://www.dementiavoices.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Dementia-Enquirers-Research-Pack.pdf

- Wolverson, E., Harrison Dening, K., Gower, Z., Brown, P., Cox, J., McGrath, V., Pepper, A., & Prichard, J. (2023). What are the information needs of people with dementia and their family caregivers when they are admitted to a mental health ward and do current ward patient information leaflets meet their needs? Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 26(3), 1227–1235. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13738

- World Health Organisation. (2004). WHO Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package: Mental Health Legislation and Human Rights (updated version). World Health Organization.