Abstract

Objectives

One of the main reasons for people with dementia to move to a dementia special care unit of a nursing home is challenging behavior. This behavior is often difficult to manage, and in the Netherlands, residents are sometimes relocated to a severe challenging behavior specialized unit. However, relocation often comes with trauma and should be prevented if possible. This study aimed to investigate the patient- and context-related reasons for these relocations.

Methods

Qualitative multiple case study using individual (n = 15) and focus group interviews (n = 4 with n = 20 participants) were held with elderly care physicians, physician assistants, psychologists, nursing staff members, and relatives involved with people with dementia and severe challenging behavior who had been transferred to a severe challenging behavior specialized unit. Audio recordings were transcribed and analyzed with thematic analysis, including directed content analysis.

Results

After five cases, data-saturation occurred. The thematic analysis identified three main processes: increasing severity of challenging behavior, increasing realization that the clients’ needs cannot be met, and an increasing burden of nursing staff. The interaction between these processes, triggered mainly by a life-threatening situation, led to nursing staff reaching their limits, resulting in relocation of the client.

Conclusion

Our study resulted in a conceptual framework providing insight into reasons for relocation in cases of severe challenging behavior. To prevent relocation, the increasing severity of challenging behavior, increasing burden on nursing staff, and increasing realization that the clients’ needs cannot be met need attention.

Introduction

Worldwide around 55 million people experience deterioration in memory, thinking, behavior, and the ability to perform everyday activities. These are symptoms of dementia, with about 10 million new cases every year (WHO, Citation2023). Dementia has a significant impact on the quality of life of people themselves but also on their caregivers, families, and society at large. About 79% of the people with dementia in the Netherlands live independently (Dutch-Alzheimer-Society, Citation2021), but many people with dementia will at some point relocate to a long-term care facility as the disease progresses and care can no longer be provided at home (Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2018).

Castle (Citation2001) defines the term ‘relocation’ as the move from one environment to another. Relocation of frail people is a complex process, often leading to trauma, referred to as relocation stress (Castle, Citation2001; Mallick & Whipple, Citation2000; McKinney & Melby, Citation2002). The relocation stress syndrome is characterized by symptoms such as anxiety, confusion, hopelessness, dependency, and withdrawal (Walker et al., Citation2007). In a scoping review that included thirteen papers studying the impact of relocation of people with dementia on mortality, morbidity and well-being, most studies found adverse health effects for people with dementia being relocated (Ryman et al., Citation2018). Other papers reported higher stress levels (Bellantonio et al., Citation2008; Falk et al., Citation2011; Mirotznik & Kamp, Citation2000; Morse, Citation2000; Walker et al., Citation2007).

In a large cross-sectional study in eight European countries exploring reasons for relocating people with dementia, challenging behavior, specifically apathy, wandering, and agitation/aggression was among the most often mentioned reasons (Afram et al., Citation2014). Although challenging behavior is found in up to half of the people with dementia who live in the community (Borsje et al., Citation2015; Savva et al., Citation2009), a systematic review of 28 studies showed that the weighted mean prevalence of having at least one neuropsychiatric symptom was, in fact up to 82% for older people with dementia living in a nursing home (Selbæk et al., Citation2013). As a result of governmental policies to enable people to live independently for as long as possible, people who finally do come to live in a nursing home are expected to have more severe challenging behavior. Therefore, in recent years, several so-called SCBS units (Severe Challenging Behavior Specialized units) have been developed in the Netherlands. Severe challenging behavior mostly includes depression, psychosis, vocally disruptive behaviors such as screaming, agitation, physical aggression, and physical violence (Brodaty et al., Citation2003). Although little is known about the prevalence and course of these extreme behaviors, two recent explorative studies showed a prevalence of about 7% for very frequent or very severe agitation and 11.5% for very frequent vocalizations (Palm et al., Citation2018; Veldwijk-Rouwenhorst et al., Citation2017, Citation2021).

Challenging behavior not only affects the well-being of the person with dementia, but is also associated with distress, work-satisfaction, and burn-out of the nursing staff (Garcia-Martin et al., Citation2023; Hazelhof et al., Citation2016; van Duinen-van den IJssel et al., Citation2018; Zwijsen et al., Citation2014, Citation2014). Although the nursing staff should provide tailored interventions (Lagerlund et al., Citation2022), the situation of a resident with severe challenging behavior can be experienced as an impasse (Veldwijk-Rouwenhorst et al., Citation2022). High levels of distress can be an attributing stressor of a crisis (Vroomen et al., Citation2013), suggesting that severe challenging behavior may directly or indirectly lead to a crisis. Given its detrimental effects on the well-being of the person with dementia and the nursing staff, in the Netherlands, the person with dementia and severe challenging behavior can receive specialist treatment, in which their own multi-disciplinary team receives support from a consulting old-age (geriatric) psychiatrist or sometimes from a specialized team from the national Centre of Consultation and Expertise (koopmans et al., Citation2017 and CCE). Although the conditions for high-quality care are present, collaboration difficulties and insufficient work processes still exist (Veldwijk-Rouwenhorst et al., Citation2022), leading to management challenges for clinicians (Carrarini et al., Citation2021). The relationship between both challenging behavior and the relational and social context of these crises might be modifiable for resolutions (Hopkinson et al., Citation2021). Yet, if all interventions are not effective, clients are often relocated to an SCBS unit. However, there is a lack of research on reasons for relocating people with dementia and severe challenging behavior from a regular dementia special care unit to an SCBS unit. This study aims to investigate reasons, both patient and context related, for the relocation of residents with dementia who display severe challenging behavior.

Design and methods

This qualitative multiple-case study focused on cases of clients with dementia who displayed severe challenging behavior and who were relocated to a SCBS unit. The Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative studies (COREQ) were used as a framework for conducting and reporting our study (Tong et al., Citation2007) and are listed in Appendix. In-depth interviews and focus groups were held to collect data. Inductive thematic data saturation was used as the guiding principle (Saunders et al., Citation2018). The expected number of necessary cases was seven, based on previous qualitative research by Veldwijk and colleagues (2022).

Participants

Participants were recruited through units participating in the D-zep network. The D-zep network is a Dutch nation-wide collaboration between long-term care facilities specialized in care for people with severe challenging behavior and dementia (Koopmans et al., Citation2022). The participants were all relatives or formal caregivers from the discharging care-facility. The following inclusion-criteria were used. In order to participate, the informants needed to be involved with: (a) a person with dementia and very severe or extreme challenging behavior who (b) had been relocated to a SCBS unit and (c) had lived in a Dementia Specialized Care-unit (DSC-unit) before their relocation that (d) had taken place less than one month ago.

Procedure

When a resident was relocated to one of the SCBS units, the researcher determined whether they met the inclusion criteria. After written informed consent from the legal representative was obtained, the involved staff of the discharging DSC-units were asked to participate.

The nursing-staff was interviewed in an online focus group discussion and an online semi-structured in-depth interview was held with the elderly care physician, psychologist and relative. The in-depth interviews were held separately to prevent hierarchical influence since it was expected that the nursing staff members would speak more freely if the treatment staff, who often was in charge of the treatment process, were absent. An initial topic list for the interviews was prepared and discussed among the co-authors. Both the focus group discussions and interviews focused on two main questions: ‘What were the clients’ characteristics and what were the ‘contextual’ factors leading to relocation?’ A researcher performed the interviews and a second researcher observed the process in the focus groups, taking notes during the interviews, asking additional questions, and observing body language and interaction between the participants. This information helped to specify, understand and gain depth within the discussion. After each interview, the researchers discussed the results and identified topics that could be explored further. The individual and focus group interviews were audio-taped, transcribed verbatim eliminating any names or privacy-related information, and coded and analyzed by a researcher and a second researcher using Atlas.ti.

Ethics

The regional Medical Ethics Committee for Arnhem-Nijmegen assessed the study and stated that it did not require ethical approval under Dutch legislation for medical trials. The study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki (World-Medical-Association, Citation2013) and the law on the protection of personal information. In order to maintain anonymity for participants, except gender and occupation, no personal information was collected. All interviewees provided written consent for participation. All their names were removed from the transcripts and only the researchers had access to the original interviews.

Data analysis

A generic qualitative approach was used to understand how participants interpret, construct or made meaning regarding their experiences (Kahlke, Citation2014; Merriam, Citation2009). Data was collected through in-depth interviews and focus groups. Content analysis was used as a strategy (Elo & Kyngas, Citation2008; Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005) and codes were generated from the data. Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) was used to search for themes and patterns within the cases and between the cases. All transcripts were coded separately by at least two researchers, developing a coding system in which codes were grouped in categories and themes. The coders discussed the codes, content and relationship between the categories and themes with each other and the whole research team. When coding the fifth case, no new codes were found, leading to the conclusion that data saturation was achieved (Saunders et al., Citation2018).

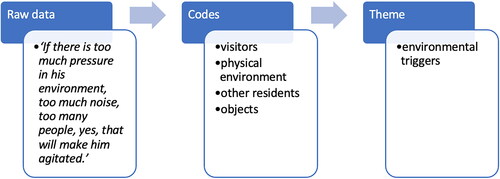

An example of raw data transferring into a theme can be found in ; in all cases, the participants were asked for context related factors influencing the clients’ behavior. The outcome of this question (raw data) was coded into codes like ‘visitors’, ‘physical environment’, ‘other residents’ and ‘objects’, eventually leading to a theme called ‘environmental triggers’.

After analysis of each case in separate meetings with the research team, the coding system was adjusted. A mind map was made for cross-case analysis of all cases, leading to main processes and subthemes. A conceptual framework was developed that represents the reasons for relocation. More detailed information about the process of data analysis can be found in Appendix.

Results

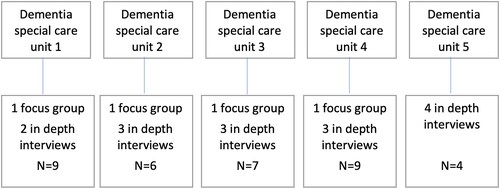

shows an overview of the focus groups and in-depth interviews of the five participating DSC-units. Unfortunately, due to organizational difficulties in DSC-unit 5, no focus group was held there. The other focus groups consisted of nursing staff with different levels of education. In total, two physician assistants, three elderly care physicians, five psychologists, four relatives, and twenty-one nursing staff members were interviewed (N = 35). shows age, sex, and type of dementia of the clients included.

Table 1. Case characteristics.

Conceptual framework

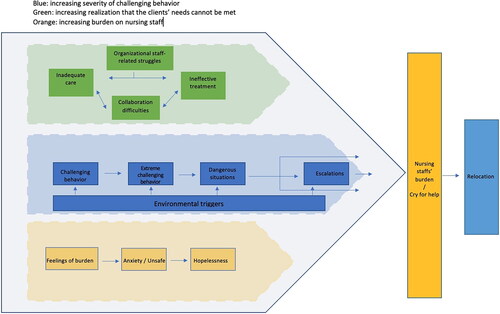

provides the identified processes toward relocating clients with severe challenging behavior to units with specific expertise on very severe challenging behavior. The central process identified was that relocation was a consequence of the nursing staff reaching their limits, often triggered by a life-threatening incident. We further identified three strongly interacting main processes consisting of seven subthemes, leading to nursing staff members reaching their limits and/or a cry for help. The main processes were as follows:

A. Increasing severity of challenging behavior.

B. Increasing realization that the clients’ needs cannot be met.

C. Increasing burden on nursing staff.

Main process A: increasing severity of challenging behavior

The first main process regarded the clients’ challenging behavior (subtheme 1) which became more and more frequent over time and increased in severity, often leading to an escalation. Initially, the clients’ behavior was manageable, but in time physical aggression towards nursing staff and other residents was more frequently reported leading to dangerous and life-threatening situations. Environmental triggers (subtheme 2) were considered to continuously enhance the challenging behavior.

Subtheme 1: clients’ behavior

The clients of the five cases showed a variety of types of challenging behavior, which were described as physical and verbal acting-out aggression toward (specific) persons or materials, hallucinations, delusions, fear, anxiety, compulsive behavior, and dependent behavior.

In all cases, the challenging behavior became more frequent, severe, unpredictable, and fluctuating over time. Also, escalations with other residents, such as pushing and strangling, were reported. Nursing staff members found it difficult to detect warning signs. Therefore, the behavior was very challenging to manage and preventing escalations was very difficult. Because of this challenging behavior, nursing staff members started to question whether the client could stay on their unit.

Quotations:

‘He started hitting, grabbing me by the throat, pushing me against the wall.’ (Nursing staff member)

‘He would look at you and smile and then when you turned away for a moment and turned back again, he would punch you in the face with a fist.’ (Nursing staff member)

‘And that behavior, it was already happening, but not to such an extent; it wasn’t until about five to six months ago, I think, that we really started to see it as problem behavior.’ (Medical treatment staff)

‘At first, it was fine. It was still acceptable then. He had the odd bad day every now and then… oh well. I wasn’t too bothered about that. I think it’s been for approximately the last six months that he’s been here, that he has changed and you had to deal with him on a daily basis.’ (Nursing staff member)

Subtheme 2: environmental triggers

Environmental triggers regarded the physical context and the interaction with other residents, visitors, and professional caregivers. The physical context, for example, a small amount of personal space and shared sanitary facilities, was considered to lead to increased challenging behavior. Furthermore, the clients were reported to have difficulties in understanding and responding to these environmental triggers with an increase of the challenging behavior as a result. Ringing telephones or physical restraints such as a locked wheelchair also resulted in increased agitation.

Quotations

‘He was extremely focused on everything that was happening around him, you only had to say, to hear, to see, to feel something, he had to be involved in everything. He had to address all those stimuli in the home.’ (Nursing staff member)

‘When I look at the department itself, in terms of the entourage, it was like the reception hall of Schiphol. The atmosphere was stark… there was no feeling of recognition at all.’ (relative)

‘If there is too much pressure in his environment, too much noise, too many people, yes, that will make him agitated.’ (Psychologist)

Main process B: the increasing realization that the clients’ needs cannot be met

The second main process identified was the teams’ increasing realization that clients’ needs could not be met. This was a result of four subthemes: organizational staff-related struggles (subtheme 3), collaboration difficulties among professional caregivers and with relatives (subtheme 4), inadequate care (subtheme 5), and ineffective treatment (subtheme 6). These subthemes also interacted: The organizational problems contributed to a shortage of knowledge and experience in working with clients’ severe challenging behavior. Furthermore, instability among the nursing and treatment staff negatively impacted their collaboration and led to a less-effective treatment, which subsequently led to even tenser collaboration.

Subtheme 3: organizational staff-related struggles

In all cases, organizational problems related to the staff, such as instability due to sickness, shortage, or high turn-over were reported. Participants described their team as understaffed and still felt the burden of the COVID-19 pandemic. In some cases, there was disagreement in vision about the treatment of the challenging behavior between nursing staff and treatment staff. For example, from an organizational perspective the treatment had to be psychosocial at all costs, whereas the nursing staff thought the solution should be found in psychotropic medication. Treatment staff members considered this discrepancy in vision as a disruptive factor treating the challenging behavior.

Subtheme 4: collaboration difficulties

The working collaboration between nursing staff and treatment staff was complex since the nursing staff mostly did not feel heard. As the challenging behavior increased, nursing staff members expected more support from the treatment staff, like advice, to be present on the unit to observe the behavior, quick adaptations of treatment policies or decisions to transfer. They questioned the treatment staffs’ recommendations, and there was no agreement about what treatment was appropriate. In fact, the nursing staff sometimes felt they were being blamed by the treatment staff for the increasing challenging behavior. On the other hand, treatment staff experienced the communication with the nursing staff as insufficient, stating that they could not make an adequate analysis of the challenging behavior due to different observations of the nursing staff members and inadequate reports. Relatives also often reported the relationship with treatment as well as nursing staff as being complex. Relatives expressed the wish for more shared decision-making and influence on the patients’ treatment. In addition to these issues, some nursing staff team members reported feeling unsafe within their team and there was an overall feeling of lack of management support.

Quotations

‘At one point we also said to the psychologist; ‘Try and be here for a whole day.’ She would sometimes come and then she would come for fifteen minutes, but you can’t sketch a whole day in fifteen minutes. And then she said; ‘well it’s better than expected.’ …… “better support, at least for them to believe what we are saying.’ (Nursing staff member)

‘Yes, there was a lot going on, and so they might not always support each other or exchange knowledge. And yes… there was quite a lot of finger pointing, at each other.’ (Psychologist)

‘I hadn’t realized there was such a lack of trust in us as therapists among that team.’ (Psychologist)

Subtheme 5: inadequate care

The clients’ highly complex care needs were very difficult for the nursing staff to meet. According to the treatment staff and even the nursing staff themselves, nursing staff experienced a lack of knowledge, skills, and competencies for dealing with clients with dementia and severe challenging behavior. In addition, treatment staff reported nursing staffs’ working routines as not being tailored to the specific needs of these clients. Treatment staff reported that nursing staff members struggled to adapt their routines and rigidly tried to continue their daily work. Furthermore, having different opinions about the appropriate treatment led to nursing staff not working together as a team, also leading to an increase in challenging behavior.

Quotations

‘What bothered her, of course, is that everyone reacted to her in a different way. There was very little clarity for her and that just brought more fears or more uncertainty.’ (Medical treatment staff)

‘But they do not apply the interventions consistently. Medications were not given, were forgotten, handling advice was not given, yes… They were not on the same page at all.’ (Medical treatment staff)

‘There was very strict adherence to a certain time for breakfast, so the lady was only allowed to set the table at 8 o’clock, while she wanted to set the table earlier in the morning. Surely that wouldn’t bother anyone? You can see that around breakfast time, that there was a lot of adherence to certain structures, in one’s own head, actually.’ (Psychologist)

Subtheme 6: ineffective treatment

Initially, interventions such as psychological advice were implemented but did not reach the desired effect. The nursing staff started questioning the psychological advice since the challenging behavior did, in fact, increase. Therefore, new interventions recommended by the psychologist had no support from the nursing staff to implement. Meanwhile, the nursing staff kept providing care, mostly hoping for the prescription of psychotropic medication. The treatment staff often consulted colleagues with more expertise, of which the nursing staff was unaware. The interventions that were started did not achieve the desired effect. In the end, just before transfer, the treatment staff reported a lack of cooperation from nursing staff in executing interventions and a lack of time investment from the nursing staff to implement the treatments correctly, leading to an inability of the multidisciplinary team to provide adequate treatment.

Quotations

‘In a short time his behavior has become more aggressive, which is why I also said: ‘I don’t think we have enough space to do a proper analysis of the behavior.’ (Psychologist)

‘Because of the increase in that agitation, we may have lost the team a bit. The willingness to really put our shoulders to the wheel and say we’re going to get this job done… that… yes… We had a contact plan and at a certain point that didn’t work either, or rather, not everyone was able to stick to it anymore.’ (Psychologist)

Main process C: the increasing burden on nursing staff

The third main process describes the impact of the clients’ behavior (subtheme 7) on the nursing staff, leading to feelings of being burdened, and reflects a process of losing hope.

As the challenging behavior became more frequent and severe, feelings of anxiety and unsafety of the nursing staff increased. The hope of finding an appropriate and effective treatment faded, leading to feelings of hopelessness.

Subtheme 7: impact of clients’ behavior

Initially, the impact of the clients’ behavior led to a feeling of being burdened among the nursing staff and relatives. These feelings differed between team members. Nursing staff members and relatives both reported challenging behavior such as agitation, restlessness and dependent behavior of moderate severity. The nursing staff reported that after a while, all their attention would be focused on the specific client. As the behavior occurred more frequently, other residents became annoyed and some escalations with other residents were reported, involving physical aggression toward nursing staff and other residents, even leading to injuries that severely impacted the nursing staff. Over time, the behavior led to emotions such as fear and irritation among the nursing staff. Several nursing staff members mentioned re-living earlier negative experiences with other clients’ behavior, leading to a further increase in fear. Nursing staff reported needing to be alert all the time and feeling overly responsible, powerless, and unable to manage the situation.

Quotations

‘Until he took a knife from a table at one point… And I just say: “Give it to me”. And he pushes me… And luckily there was a chair there, otherwise I would have fallen over.’ (Nursing staff member)

‘I said at home: “If something happens to me tonight… I have sent an email to the treatment team, so it’s there in black and white that the situation is unmanageable and not safe. So if something happens to me tonight… Well, I think he will squeeze my throat one day.”’ (Nursing staff member)

Relationship between the three main processes

As mentioned earlier, the three main processes interacted. Starting with the clients’ behavior, the frequency and severity of the challenging behavior increased over time, influenced by environmental triggers. Next, organizational problems, shortage of knowledge and experience, inadequate care and ineffective treatments increased the challenging behavior. These organizational problems, shortage of knowledge and experience, inadequate care and ineffective treatment also made nursing staff feel increasingly hopeless. Additionally, their feelings of irritation, anxiety, and hopelessness increased as a result of the behavior and its consequences, especially because of escalations. Moreover, in some cases these feelings, in turn, affected the nursing staffs’ reaction to the client in such a way that it led to a further increase of the challenging behavior. Together, the three main processes increased the nursing staffs’ burden, in some cases resulting in a cry for help and demanding a relocation.

Enough is enough

Even though the treatment staff mostly still had hopes of finding an effective treatment, a life-threatening escalation made the nursing staff draw their boundaries toward the treatment staff, and express that they were unable to continue providing care for the client and therefore demanded a transfer to a SCBS unit. At that point, the decision to transfer the client to a SCBS unit was made, and the relocation process started.

Quotations

‘The signal came from the team. We did see several possibilities to support him in different ways so that he could stay.’ (Psychologist)

‘We still had ideas that we wanted to try out, but… There was simply no more support for the situation.’ (Medical treatment staff)

‘I then called the doctor because I just didn’t think that was safe and then I said: “I just want something to change today, tonight, because it’s almost night.”’ (Nursing staff member)

‘Then I gathered all my courage… I walked over to the doctor and then I told him plain as day: “He has to go. He has to get out of here.” And then the doctor said: “Yes, but we are trying to find a place.” And then I said: “No… he has to get out of here.” And then they started making a real effort with the phone calls.”’ (Nursing staff member)

Discussion

This study shows the complexity of treating people with dementia and severe challenging behavior in a DSC unit setting. The increasing severity of challenging behavior, and the realization that the clients’ needs cannot be met, combined with a loss of hope in finding an appropriate and effective treatment, led to nursing staff being burdened to such an extent that they demanded relocation of the client. The factors leading to this relocation interacted. We found a variety of challenging behaviors that all became more frequent, severe, unpredictable, and fluctuating over time. Triggers from the physical context and interaction with others resulted in an increase of clients’ challenging behavior. In addition to organizational problems among staff, collaboration difficulties between nursing staff, treatment staff, and relatives were an issue as well. All these factors resulted in inadequate care and ineffective treatment that led to the realization that the clients’ needs could not be met and the challenging behavior became more severe.

The complexity of the cases and our findings about the impact of client and contextual factors are partly in line with earlier studies. As mentioned, previous literature found that severe challenging behavior is associated with (very) high distress levels in nursing staff (van Duinen-van den IJssel et al., Citation2018; Zwijsen et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, high workload, staffing shortage, and interactions with co-workers were also found to have an additional effect on distress levels in nursing staff (Edvardsson et al., Citation2009; Schaefer & Moos, Citation1996). Our research supports these findings. Moreover, our study shows that the interaction between nursing staff and treatment staff had an additional effect on the levels of distress of nursing staff. They were supposed to carry out a treatment plan that they did not support or trust but that was directed by the treatment staff. Nursing staff reported not feeling heard by the treatment staff, leading to high levels of distress and the loss of hope in finding a resolution. This loss of hope was recently described by Veldwijk-Rouwenhorst et al. (Citation2022), although they found that some staff members lost hope while others kept searching for a solution to manage the behavior in situations of severe challenging behavior that were experienced as an impasse. In line with our study, they identified several characteristics and attitudes of staff members involved in these situations; interaction issues within staff member groups; and interaction issues among (groups of) staff that contributed to this impasse experience.

The central process we identified is in line with results from a review conducted by Vroomen et al. (Citation2013) about processes in crisis. They define crisis in dementia as a process where a stressor causes an imbalance requiring an immediate decision to be made which leads to a desired outcome and therefore a resolution of the crisis. If the crisis is not solved, the cycle continues (Vroomen et al., Citation2013). In our study, many decisions were made by treatment and nursing staff, without the desired outcomes. Therefore, the cycle continued, ultimately leading to losing hope and relocation of the client. Today, life in DSC units is mostly group oriented and consists of specific structured day programs and working routines. Our study reported nursing staff members trying to keep the client with severe challenging behavior in these daily routine programs of the DSC units. These attempts led to an increase in challenging behavior. Therefore, it is questionable whether this specific group of people with dementia and severe challenging behavior benefits from group-structured programs. Veldwijk-Rouwenhorst et al. (Citation2022) mention the possibility that small-scale units are not suitable for clients with extreme challenging behavior, which raises the question of what a supportive environment for this client group requires and if and under what conditions they benefit from treatment in intensive specialist care units (Brodaty et al., Citation2003).

A recent group-concept map study identified three domains of successful treatment for this specific client group (van Voorden et al., Citation2023). First, successful treatment should be about the well-being of the client and all the people directly involved. Next, multidisciplinary analysis and treatment, comprising multidisciplinary analysis, process conditions, reduction in psychotropic drugs, and person-centered treatment must be in place. Third, the attitudes and skills of those involved, comprising consistent approaches by the team, understanding behavior, knowing how to respond to behavior, and open attitudes were found to be crucial.

In our research, all three aspects mentioned above showed inadequacies. For example, the overall treatment focus was on managing the challenging behavior and less on the well-being of all involved. Treatment staff struggled to get full insight into the challenging behavior because nursing staff members reported the behavior from their personal perspective instead of integrating all colleagues’ experiences. In our study, nursing staff members reported feelings of doubt about the treatment from the start. The treatment staffs’ recommendations changed over time and were interpreted differently and sometimes even ignored by the nursing staff. Agreements and clear problem definitions with a treatment plan and evaluations appeared to be absent or were not supported by all caregivers.

Strengths and limitations

Clients with dementia and severe challenging behavior on DSC units are often transferred to SCBS units. Little research has been done into this specific group of clients, no known research has been done into reasons to transfer in this specific group, although it is known that the relocation of frail people often leads to relocation trauma (Castle, Citation2001; Mallick & Whipple, Citation2000; McKinney & Melby, Citation2002). A strength of this study is the in-depth insight it provides into reasons for transfer in this specific client group by using rigorous qualitative methodology with inductive thematic data saturation as a guiding principle (Saunders et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, multiple researchers were involved, all relevant stakeholders in the cases participated, and data triangulation was achieved by combining individual and focus group interviews and analytical techniques. This further strengthened the transferability, dependability, and confirmability of the data (Korstjens & Moser, Citation2018). The resulting conceptual framework provides a detailed overview of the central process with its three main processes and the interaction between the sub-themes.

As the data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, all interviews were held online. The interaction between the focus group participants was therefore more difficult to analyze. However, to improve reliability, investigator triangulation was applied by involving two researchers in each of the interviews. Furthermore, due to COVID-19 restrictions, the care provided to the clients in this study differed from regular care. For example, team meetings for reflection and training could not take place. Therefore, the management of the challenging behavior may have been even more difficult. Nevertheless, according to participants, the difficulties mentioned within both the main processes and the subthemes were all present before the COVID-19 restrictions. Selective sampling may have occurred since the participating DSC-units all had a SCBS-unit in their region and they might have been more inclined to transfer people with dementia and severe challenging behavior to this SCBS-unit. Yet, this assumption has not been investigated in our study.

Conclusion and implications

Relocating frail people often comes with trauma and should therefore be prevented. Our study resulted in a conceptual framework which may have important implications for daily practice; the identified processes and themes may form the basis of information gathering in cases of increasing challenging behavior. Assessing these will provide insight into the complex processes that caring for severe challenging behavior involves and may help to prevent relocation. Early detection is needed to manage these extreme challenging behaviors and to prevent further escalation. In addition to managing the challenging behavior itself, the well-being of all people involved should get attention and be seen as treatment-outcome. Our results suggest that the wellbeing of the nursing staff did not receive the necessary attention in the studied cases. It showed how life-threatening situations on DSC units occur and gave insights into the working conditions of nursing staff. Further research may include cases without transfers and give insight in how relocation was prevented. Overall, it can be stated that nursing staff members tend to go over their limits and experience difficulties in standing up for themselves. Thus, we encourage more research about relationship-centered care to enhance the self-care and therefore quality of care of professional teams and relatives.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Afram, B., Stephan, A., Verbeek, H., Bleijlevens, M. H. C., Suhonen, R., Sutcliffe, C., Raamat, K., Cabrera, E., Soto, M. E., Hallberg, I. R., Meyer, G., & Hamers, J. P. H, RightTimePlaceCare Consortium. (2014). Reasons for institutionalization of people with dementia: Informal caregiver reports from 8 European countries. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 15(2), 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.09.012

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2018). 2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 14(3), 367–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.001

- Bellantonio, S., Kenny, A. M., Fortinsky, R. H., Kleppinger, A., Robison, J., Gruman, C., Kulldorff, M., & Trella, P. M. (2008). Efficacy of a geriatrics team intervention for residents in dementia-specific assisted living facilities: Effect on unanticipated transitions. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 56(3), 523–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01591.x

- Borsje, P., Wetzels, R. B., Lucassen, P. L., Pot, A. M., & Koopmans, R. T. (2015). The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in community-dwelling patients with dementia: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(3), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610214002282

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brodaty, H., Draper, B. M., & Low, L. F. (2003). Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: A seven-tiered model of service delivery. Medical Journal of Australia, 178(5), 231–234. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05169.x

- Carrarini, C., Russo, M., Dono, F., Barbone, F., Rispoli, M. G., Ferri, L., Di Pietro, M., Digiovanni, A., Ajdinaj, P., Speranza, R., Granzotto, A., Frazzini, V., Thomas, A., Pilotto, A., Padovani, A., Onofrj, M., Sensi, S. L., & Bonanni, L. (2021). Agitation and dementia:L prevention and treatment strategies in acute and chronic conditions. Frontiers in Neurology, 12, 644317. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.644317

- Castle, N. G. (2001). Relocation of the elderly. Medical Care Research and Review: MCRR, 58(3), 291–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/107755870105800302

- CCE. https://www.cce.nl/english

- Dutch-Alzheimer-Society. (2021). Factsheet cijfers en feiten over dementie. https://www.alzheimer-nederland.nl/factsheet-cijfers-en-feiten-over-dementie

- Edvardsson, D., Sandman, P. O., Nay, R., & Karlsson, S. (2009). Predictors of job strain in residential dementia care nursing staff. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00891.x

- Elo, S, & Kyngas, H. (2008) The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–15.

- Falk, H., Wijk, H., & Persson, L. O. (2011). Frail older persons’ experiences of interinstitutional relocation. Geriatric Nursing (New York, N.Y.), 32(4), 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2011.03.002

- Garcia-Martin, V., Canto de Hoyos-Alonso, M., Delgado-Puebla, R., Ariza-Cardiel, G., & Del Cura-Gonzalez, I. (2023). Burden in caregivers of primary care patients with dementia: Influence of neuropsychiatric symptoms according to disease stage (NeDEM project). BMC Geriatrics, 23(1), 525. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04234-0

- Hazelhof, T. J., Schoonhoven, L., van Gaal, B. G., Koopmans, R. T., & Gerritsen, D. L. (2016). Nursing staff stress from challenging behaviour of residents with dementia: A concept analysis. International Nursing Review, 63(3), 507–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12293

- Hopkinson, J. B., King, A., Mullins, J., Young, L., Kumar, S., Hydon, K., Muthukrishnan, S., Elliott, F., & Hopkinson, M. (2021). What happens before, during and after crisis for someone with dementia living at home: A systematic review. Dementia, 20(2), 570–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301220901634

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Kahlke, R. M. (2014). Generic qualitative approaches: Pitfalls and benefits of methodological mixology. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 13(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691401300119

- Koopmans, R., Pellegrom, M., van der Geer, E. R. (2017). The Dutch move beyond the concept of nursing home physician specialists. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 18(9), 746–9.

- Koopmans, R. T., Leerink, B., & Festen, D. A. (2022). Dutch long-term care in transition: A guide for other countries. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 23(2), 204–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.09.013

- Korstjens, I., & Moser, A. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. European Journal of General Practice, 24(1), 120–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092

- Lagerlund, H., Thunborg, C., & Sandborgh, M. (2022). Behaviour-directed interventions for problematic person transfer situations in two dementia care dyads: A single case design study. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 261. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02952-5

- Mallick, M. J., & Whipple, T. W. (2000). Validity of the nursing diagnosis of relocation stress syndrome. Nursing Research, 49(2), 97–100. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200003000-00006

- McKinney, A. A., & Melby, V. (2002). Relocation stress in critical care: A review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 11(2), 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00577.x

- Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey – Bass.

- Mirotznik, J., & Kamp, L. L. (2000). Cognitive status and relocation stress: A test of the vulnerability hypothesis. The Gerontologist, 40(5), 531–539. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/40.5.531

- Morse, D. L. (2000). Relocation stress syndrome is real. American Journal of Nursing, 100(8), 24AAAA. https://doi.org/10.2307/3522152

- Palm, R., Sorg, C. G. G., Strobel, A., Gerritsen, D. L., & Holle, B. (2018). Severe agitation in dementia: An explorative secondary data analysis on the prevalence and associated factors in nursing home residents. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD, 66(4), 1463–1470. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-180647

- Ryman, F. V. M., Erisman, J. C., Darvey, L. M., Osborne, J., Swartsenburg, E., & Syurina, E. V. (2018). Health effects of the relocation of patients with dementia: A scoping review to inform medical and policy decision-making. The Gerontologist, 59(6), e674–e682. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny031

- Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

- Savva, G. M., Zaccai, J., Matthews, F. E., Davidson, J. E., McKeith, I., & Brayne, C, Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. (2009). Prevalence, correlates and course of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in the population. British Journal of Psychiatry: Journal of Mental Science, 194(3), 212–219. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.049619

- Schaefer, J. A., & Moos, R. H. (1996). Effects of work stressors and work climate on long-term care staff’s job morale and functioning. Research in Nursing & Health, 19(1), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199602)19:1<63::Aid-nur7>3.0.Co;2-j

- Selbæk, G., Engedal, K., & Bergh, S. (2013). The prevalence and course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing home patients with dementia: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 14(3), 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2012.09.027

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- van Duinen-van den IJssel, J. C. L., Mulders, A. J. M. J., Smalbrugge, M., Zwijsen, S. A., Appelhof, B., Zuidema, S. U., de Vugt, M. E., Verhey, F. R. J., Bakker, C., & Koopmans, R. T. C. M. (2018). Nursing staff distress associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms in young-onset dementia and late-onset dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 19(7), 627–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.10.004

- van Voorden, G., Koopmans, R. T. C. M., Smalbrugge, M., Zuidema, S. U., van den Brink, A. M. A., Persoon, A., Oude Voshaar, R. C., & Gerritsen, D. L. (2023). Well-being, multidisciplinary work and a skillful team: Essential elements of succesful treatment in severe challenging behavior in dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 27(12), 2482–2489. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2023.2169248

- Veldwijk-Rouwenhorst, A. E., Smalbrugge, M., Wetzels, R., Bor, H., Zuidema, S. U., Koopmans, R., & Gerritsen, D. L. (2017). Nursing home residents with dementia and very frequent agitation: A particular group. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(12), 1339–1348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2017.08.002

- Veldwijk-Rouwenhorst, A. E., Zuidema, S. U., Smalbrugge, M., Bor, H., Wetzels, R., Gerritsen, D. L., & Koopmans, R. T. C. M. (2021). Very frequent physical aggression and vocalizations in nursing home residents with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 25(8), 1442–1451. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1786799

- Veldwijk-Rouwenhorst, A. E., Zuidema, S. U., Smalbrugge, M., Persoon, A., Koopmans, R. T. C. M., & Gerritsen, D. L. (2022). Losing hope or keep searching for a golden solution: An in-depth exploration of experiences with extreme challenging behavior in nursing home residents with dementia. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 758. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03438-0

- Vroomen, J. M., Bosmans, J. E., van Hout, H. P. J., & Rooij de, S. E. (2013). Reviewing the definition of crisis in demantia care. BMC Geriatrics, 13(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-13-10

- Walker, C. A., Curry, L. C., & Hogstel, M. O. (2007). Relocation stress syndrome in older adults transitioning from home to a long-term care facility: Myth or reality? Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 45(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20070101-09

- WHO. (2023). Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. https://www.alz.org/media/documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf

- World-Medical-Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical resarch involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20),2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053.

- Zwijsen, S. A., Kabboord, A., Eefsting, J. A., Hertogh, C. M., Pot, A. M., Gerritsen, D. L., & Smalbrugge, M. (2014). Nurses in distress? An explorative study into the relation between distress and individual neuropsychiatric symptoms of people with dementia in nursing homes. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(4), 384–391. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4014

- Zwijsen, S. A., Smalbrugge, M., Eefsting, J. A., Twisk, J. W. R., Gerritsen, D. L., Pot, A. M., & Hertogh, C. (2014). Coming to grips with challenging behavior: A cluster randomized controlled trial on the effects of a multidisciplinary care program for challenging behavior in dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 15(7), e531-531–531.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.04.007