Abstract

Objectives

Patient-family member dyads experience transitions through illness as an interdependent team. This study measures the association of depression, anxiety, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of older adult primary care patient-family member dyads.

Methods

Baseline data from 1,808 patient-family member dyads enrolled in a trial testing early detection of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in primary care. Actor-Partner Independence Model was used to analyze dyadic relationships between patients’ and family members’ depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD-7), and HRQOL (SF-36 Physical Component Summary score and Mental Component Summary score).

Results

Family member mean (SD) age is 64.2 (13) years; 32.2% male; 84.6% White; and 64.8% being the patient’s spouse/partner. Patient mean (SD) age is 73.7 (5.7) years; 47% male; and 85.1% White. For HRQOL, there were significant actor effects for patient and family member depression alone and depression and anxiety together on their own HRQOL (p < 0.001). There were significant partner effects where family member depression combined with anxiety was associated with the patient’s physical component summary score of the SF-36 (p = 0.010), and where the family member’s anxiety alone was associated with the patient’s mental component summary score of the SF-36 (p = 0.031).

Conclusion

Results from this study reveal that many dyads experience covarying health status (e.g. depression, anxiety) even prior to entering a caregiving situation.

Introduction

The involvement of family members in supporting and caring for other family members as they age is a common familial experience given the increase in life expectancy and the average number of years that older adults live with a physical or cognitive disability before death (Arias et al., Citation2016; National Center for Health Statistics (US),), Citation2018; Spillman et al., Citation2014; Zahran et al., Citation2005). When older family members experience illness and functional and cognitive decline, support in the form of caregiving increases (Kelley & Bollens-Lund, Citation2018). Dyads, such as spouses or parent-child, experience illness and disability as an interdependent team and the health and well-being of the dyad covaries (Lyons & Lee, Citation2018). For example, studies have found an impact on family members when the patient has cancer or serious mental health conditions such as schizophrenia and bipolar disease (Golics et al., Citation2013). In some instances, the impact on family members is interdependent, meaning the existence of a condition in one family member could influence a condition in another family member. This interdependence appears to be present among both spousal and non-spousal dyads (Clark & Mills, Citation2012; Ferraris et al., Citation2022; Le et al., Citation2018). Studies have demonstrated that psychological distress including depression and anxiety have important influences on quality of life overall and health related quality of life (Liang et al., Citation2022) and are correlated among spouses and immediate family members (Gaynes et al., Citation2002; Holmes & Deb, Citation2003; Kim et al., Citation2008)

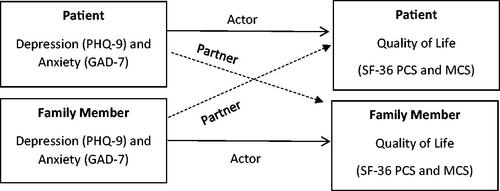

While measured differently across studies, the relationship among depression and the construct of quality of life is well documented with studies showing that depression predicts worse health-related quality of life among older adults (Ribeiro et al., Citation2020; Sivertsen et al., Citation2015). In turn, this study analyzed the baseline data from the Caregivers Outcomes of Alzheimer’s Disease Screening (COADS) trial to investigate the correlations and associations of important dyadic factors such as quality of life and mental health outcomes, such as depression and anxiety (Fowler et al., Citation2020). COADS is a large randomized clinical trial testing the impact of early identification of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) on family members of older adults who report most likely becoming the older adults’ primary caregiver if they develop a serious illness. We selected outcomes for COADS and designed these analyses using the theory of dyadic illness management (Lyons & Lee, Citation2018). This framework is grounded in the idea that dyadic quality of life and mental health outcomes are interdependent. These changes could be positive or negative for the family member or the patient and could be related to positive or negative outcomes, which could influence both members of the dyad. In addition, using an actor-partner interdependent model (APIM) (Kenny et al., Citation2006) is suitable for this analysis, as the APIM methodology is designed to provide an explanation of the interdependence between dyads—as one person’s emotion, cognition, and behaviors influence the emotion, cognition, and behaviors of another (Kelley et al., Citation2003; Kelley & Thibaut, Citation1978). The purpose of this study, therefore, is to identify the dyadic constructs that are measured in the COADS trial and to determine if these factors at baseline and prior to any detection of cognitive impairment are associated with family members and older adult primary care patient’s quality of life, depression, and anxiety.

Methods

Study design and participants

Data for this study were collected from baseline assessments of all primary care patients and their family members in an ADRD screening trial. A complete description of the study protocol has been previously published (Fowler et al., Citation2020). Eligible participants included dyads of primary care patients age ≥65 years without a diagnosis of ADRD or prescription for an antidementia medication and a family member or individual who the patient identified as the person most likely to provide care to them, if they needed it. Other inclusion criteria for patients included being community-dwelling, English-speaking, and having an eligible family member willing to participate in the study. Family member eligibility criteria included being at least 18 years old, English speaking, and having regular access to a telephone. All participants recruited in-person provided written informed consent, while all participants recruited via telephone provided verbal informed consent. Following informed consent procedures, the dyads completed an in-person or telephone baseline assessment. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of a large midwestern university in the United States.

Measurements

Patient and family member depression and anxiety were measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). The PHQ-9 is a nine-item depression scale with a total score from 0 to 27 (Kroenke & Spitzer, Citation2002), and the GAD-7 is a seven-item anxiety scale with a total score from 0 to 21 (Spitzer et al., Citation2006). Both of these scales are derived from the Patient Health Questionnaire and have good internal consistency and test–retest reliability, as well as convergent, construct, criterion, procedural, and factorial validity for the diagnosis of major depression disorder and generalized anxiety disorder in adults (Löwe et al., Citation2004; Spitzer et al., Citation2006). In addition, the PHQ-9 has demonstrated to have evidence of reliability and validity among older adults and their informal caregivers (Austrom et al., Citation2014; Kroenke & Spitzer, Citation2002). Likewise, the GAD-7 has demonstrated evidence of reliability and validity among older adults (Wild et al., Citation2014). For these analyses, depression and anxiety were the actor-predictor variables.

Patient and family member health-related quality of life (hereafter, HRQOL) was measured by the Physical Component Scale and Mental Component Scale of the 36-item Short Form Health Survey–Version 2 (SF-36v2). The SF-36 is a multipurpose, short-form health survey with 36 questions that measures patient and family members’ HRQOL including mental, physical, and social functioning (Stewart et al., Citation1988; Ware et al., Citation1993). It includes one multi-item scale that assesses eight concepts that have shown to be interconnected among family members: physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health. These concepts are aggregated into two components, a physical component summary score (PCS) and mental component summary score (MCS). Some items included in the PCS ask respondents indicate how much their health limits them in ‘vigorous activities, such as running, lifting heavy objects, participating in strenuous sports’, ‘moderate activities, such as moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling, or playing golf’, ‘lifting or carrying groceries’, climbing several flights of stairs’, and ‘bathing or dressing themselves’. A few items in the MCS ask respondents to indicate how much of the time they have felt the following ways in the past four weeks: ‘have you felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up?’, ‘have you felt calm and peaceful?’, and ‘have you been a very nervous person’. Scores are transformed on a scale of 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better health and normed average scores of 50 with a standard deviation of 10 (Cech & Martin, Citation2012). The SF-36 is an appropriate quality of life measure for older adults and their family members (Counsell et al., Citation2006; Liang et al., Citation1985; Wetherell et al., Citation2004). We measured HRQOL using the mental health component summary score and the physical health summary component score of the SF-36 which were the actor-partner outcome variables for these analyses.

Patient neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage was used as a covariate and was assessed using the area deprivation index (ADI) (Kind & Buckingham, Citation2018; Singh, Citation2003; Singh & Siahpush, Citation2002). Previous studies have linked neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage with lower well-being in older adults (Gill et al., Citation2021). The ADI is a composite score calculated from 17 measures of income, employment, education, and housing information collected from 2009 to 2013 data from a large national study (United States Census Bureau, Citation2022). A research team at the University of Wisconsin calculated the ADI of each neighborhood in the U.S. and provided these scores for download through the Neighborhood Atlas (Kind & Buckingham, Citation2018). ADI scores are totaled from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more socioeconomic disadvantage.

Patient comorbidity was assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) (Charlson et al., Citation1987). The CCI is a weighted score calculated from the presence of 19 medical comorbid conditions. A higher total score indicates higher mortality risk and presence of more comorbid conditions.

Baseline sociodemographic variables such as patient and family member age, sex, race, ethnicity, education level, self-reported income level, and the family member’s relationship to the patient were used as covariates for the analyses.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics including mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and frequency and percent in each category for categorical variables were calculated. We used the actor-partner interdependence model (APIM) (Kenny et al., Citation2006) to examine the interdependence of patient and family member HRQOL, using patient and family member’s depression and anxiety status as predictors (See ). The APIM provides an approximation for the actor effects (e.g. the actor effects for patients were the patient’s depression and/or anxiety’s association with their own physical component score (PCS) and mental component score (MCS); the actor effects for the family members were the family member’s depression and/or anxiety’s association with their own PCS and MCS scores). In summary, actor effects describe how each dyadic member’s predictor variable is related to their own outcome variable. Partner effects were analyzed as well (e.g. the patient’s depression and/or anxiety’s association with family member’s PCS and MCS scores; the family member’s depression and/or anxiety’s association with the patient’s PCS and MCS scores). Therefore, partner effects describe how one dyad member’s predictor variable is associated with the other dyad member’s outcome variable. We utilized a repeated measures to conduct the APIM analysis. Measurements within the same dyad were treated as repeated measurements to link patients with their family members and heterogeneous compound symmetry was specified for the covariance structure. The APIM is particularly valuable as it can shed light on the influences that each member of the patient-family dyad has on themselves (actor effects) as well as the influences each member has on the other member (partner effects, or bidirectionality) and within a single model. In the current study, partner effects in the APIM are defined as a measure of bidirectionality, i.e. the impact of the patient’s depression and anxiety status on the family members HRQOL (for a theoretical model, see ). Essentially, the APIM is able to take into account each member’s interdependence on the other member (Garcia et al., Citation2015).

Results

Descriptive Information on sample

shows the baseline characteristics of patients and family members. The mean age of family members was 64.2 (12.9) years, 32.3% were male, and 84.6% reported their race as White. Among the family members, 64.8% were the spouse or partner of the patient and 84.8% had some college, a college degree, or postgraduate education. Among all patients, 47% were male and 85.1% reported their race as White. The mean (SD) age was 73.7 (5.7) years, and 81.8% had attained education beyond high school. Regarding income, 81.3% of patients and 82.8% of family members reported their income level as comfortable. Additionally, baseline measures for HRQOL (SF-36 PCS score and MCS), depression (PHQ-9), and anxiety (GAD-7) were similar to published norms and results from other large studies of similar populations (Fowler et al., Citation2020) and patient comorbidity status as measured by the Charleson Comorbidity Index was correlated with their SF-36 PCS (p < 0.001) (not shown on table)

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patient-family member dyads.

Actor and partner effects

Physical component summary of HRQOL

We found actor-effects for both patient and family member HRQOL as measured by the physical component summary scale (PCS) (). These actor effects describe how each dyad member’s predictor variable is associated with their own outcome variables. Patients with depression only (β=-9.03, p < 0.001) and patients with both depression and anxiety (β = −7.04, p < 0.001) had lower PCS scores when compared to patients with no depression or anxiety. Similarly, family members with depression only (β = −5.31, p < 0.001) and family members with depression and anxiety (β = −5.34, p < 0.001) had lower PCS scores when compared to family members with no depression or anxiety. We found a partner-effect of family members with depression and anxiety combined being associated with lower patient PCS scores when compared to family members with no depression or anxiety (β = −1.76, p = 0.018).

Table 2. Actor-partner effects of patient and family member depression and anxiety on quality of life.

Mental component summary of HRQOL

We also found actor-effects for both patient and family member HRQOL as measured by the mental component summary (MCS) scale (). Patients with depression only (β = −4.36, p < 0.001), anxiety only (β = −5.52, p < 0.001), and both depression and anxiety (β = −12.93, p < 0.001) are more likely to have lower patient MCS scores compared to patients with no depression or anxiety. Similarly, family members with depression only (β = −4.60, p < 0.001), anxiety only (β = −3.81, p < 0.001), and both depression and anxiety (β = −12.86, p < 0.001) are more likely to have lower family member MCS scores compared to family members with no depression or anxiety. We found a partner effect regarding patient MCS scores—family members with anxiety only were associated with lower patient MCS (β = −1.48, p = 0.030).

Discussion

As adults age and experience illness, family members are often involved and frequently become participants in the management and provision of health and supportive care for their older family members (Doherty, Citation1991). As a result, the health and wellbeing of older adults and their family members is often interconnected, and dyads can influence each other’s emotions, wellbeing, and other outcomes (Wong & Hsieh, Citation2019). In this large sample of patient-family member dyads, we found varied actor and partner effects of depression and anxiety’s relationship with the two component score that measure HRQOL. These findings reinforce the concept that not only do dyadic members influence their own health, but the family member’s depression and anxiety also influences the patient’s HRQOL (Revenson et al., Citation2016). In addition, this study expands upon the complex nature in which depression and anxiety are related to dyadic HRQOL.

Actor effects

While the literature supports that each member of a dyad influences their own and each other’s health (Revenson et al., Citation2016; Wong & Hsieh, Citation2019), our study further promotes the complexity of this concept. More specifically, the relationship between older primary care patients and their family members depression and anxiety with their own/each other’s HRQOL is rather nuanced. For example, regarding patient and family member physical component of HRQOL, an actor-effect was only observed for patients and family members with depression only or the presence both depression and anxiety. Meaning that anxiety itself is not associated with one’s own physical functioning. This was not the case for patient and family member mental component of HRQOL where an actor-effect was observed for patients and family members with the presence of depression only, anxiety only, or both depression and anxiety. Overall, depression and depression combined with anxiety were associated with both physical and mental components of HRQOL for both patients and their family members. Having both depression and anxiety was particularly worse for mental components of health-related quality of life than having either alone.

Partner effects

Family wellbeing and family health are essential elements in the care of older adults. By studying the partner effects among dyads of older primary care patients and their family members in a pre-caregiving state, we investigated the relationship between dyads depression, anxiety and HRQOL. We found modest partner effects in that family member depression and anxiety were associated with worse patient physical components summary scores. These findings suggest the importance of screening family members for anxiety and depression in primary care. Family members commonly neglect their own needs while providing care (Bakas et al., Citation2016). As a result, many family members suffer from depression and anxiety, that might impact the patient’s physical functioning. Interestingly, family members with anxiety only were associated with worsened patient mental component summary scores of HQOL. The fact that family member depression, or depression combined with anxiety, were not associated with the patient’s mental component summary score, might have been because 73.5% of family members had no depression or anxiety at baseline. It is possible that these partner effects might have emerged if family members with no depression or anxiety were removed from the analysis. While our unadjusted analysis indicated partner effects for both the patients and family members, we found no significant partner effects for patient depression only, anxiety only, or depression and anxiety combined on family member HRQOL (physical or mental component summary scores) when adjusting for covariates. This could also be because 70.2% of patients had no depression or anxiety. Though patient depression partner effects were not significant in this sample the direction of the hypothesized relationship was in the direction we suspected, however the relationship was not significant. While both observations are not significant, it’s possible that we will see more patient effects on family member HRQOL over time as the family member takes on more caregiver roles.

As adults age and experience changes in cognitive and physical function, those changes can impact their family members. The interdependence of family member health-related quality of life is especially noted when they are caring for a spouse with ADRD (Hsu et al., Citation2023). Currently, half of Americans with ADRD never receive a formal diagnosis, and many people with ADRD receive care from their family (Friedman et al., Citation2015). Despite this, there is no guiding consensus for early identification of people who have ADRD or who are at risk of ADRD due to a lack of evidence of the risks and benefits of screening and early detection of ADRD. Results from this study reveal that many dyads are experiencing covarying mental health status (e.g. depression, anxiety) even prior to entering a caregiving situation. These are important findings for healthcare and home and community-based providers who serve older patient populations. It demonstrates that identifying needs of family members to improve patients’ outcomes will require understanding the interrelationship between dyadic outcomes. Additionally, our study establishes the nature of dyadic health between older primary care patients and their family members, in what may be the beginning or pre- caregiving experience. Future work in this area should include considerations of the impact on family members and target screening for depression and anxiety along with cognitive screening among both older patient populations. Additionally, the development of interventions should address the individual (actor) and dyadic (partner) effects of anxiety and depression on HRQOL for these populations.

There are important limitations to note about these analyses. First, the COVID-19 pandemic, which started at month 17 of our 34-month recruitment period may have affected how older adults and family members reported depression, anxiety, and HRQOL at baseline in a way that is different from dyads recruited pre-COVID-19 and in ways that are unmeasurable from the outcomes that exist as being interconnected in health and wellbeing. Though, it should be noted that a prior study using this sample found no differences in depression and anxiety in patients and family members recruited pre- and post-COVID-19 (Seibert et al., Citation2022). Second, the large sample size and statistically significant results of the outcomes may not all translate into clinical significance for the different outcomes examined. Third, the cross-sectional nature of this analysis makes it difficult to disentangle the bidirectionality of our predictor variables (depression and anxiety) and outcome variables (PCS and MCS of the SF-36 measure of health-related quality of life). Longitudinal analyses are warranted to better understand the directionality of these measures. However, a literature review of the relationship between older adult (mean age ≥60 years) depression and quality of life found that baseline depression was predictive of poorer quality of life at follow-up in longitudinal studies (Sivertsen et al., Citation2015). Lastly, these analyses use baseline data only and did not include a variable of whether the dyad was randomized to ADRD screening. There may be important differences in the association of dyadic outcomes if the patient was screened or experiencing early signs of ADRD or if the family member suspected the patient has cognitive impairment. Future studies that evaluate dyadic associations over time and account for older adults’ cognitive status may reveal more about important influences of cognitive impairment on HRQOL, depression, and anxiety in dyads.

The interdependent relationships found in our study highlight a dyadic and family-oriented approach to needed to provide wholistic care to older adults. This is particularly important as the older adults require more care and support from family members as cognitive function declines. The outcomes used for these analyses are the primary outcomes for the COADS trial, a large, longitudinal trial testing the impact of ADRD screening on family members of older adults (Fowler et al., Citation2020). The hypothesis for our trial is that early identification of ADRD in older adults may have important but not yet measured risks and benefits for family members (Fowler et al., Citation2020; Patnode et al., Citation2020).

Conclusion

In older adult primary care patient-family member dyads, patient and family member depression and anxiety are related to their own HRQOL (PCS and MCS of the SF-36). Additionally, family members with combined depression and anxiety were associated with patient’s physical HRQOL, while family members with anxiety only were associated with patient mental HRQOL. Given the influence of family member mental health has on the patient’s HRQOL, routine depression and anxiety screenings among family members in clinical settings are necessary. Future research should further explore dyadic health through the transition of patient illness as the family member takes on the role of the primary caregiver.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all the people who agreed to participate in this project and the staff who worked to make this project a success. The authors used baseline data from the Caregivers Outcomes of Alzheimer’s Disease Screening (COADS) trial. The COADS trial is pre-registered at NCT03300180. Data and analytic plan are described in the methods and will be made available to fellow researchers upon request at the conclusion of the trial.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [N.R.F], upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

M.A.B served as a paid consultant or a member of advisory board for Eisai, Merck, Biogen, Acadia, Lilly, Genentech. M.A.B also co-founded the following companies: PPHM, LLC; RestUP LLC, BlueAgilis, Inc; and DigiCare Realized, Inc.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arias, E., Heron, M., & Xu, J. (2016). United States life tables, 2012. National Vital Statistics Reports: From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, 66(4), 1–64.

- Austrom, M. G., Lu, Y. Y.-F., Perkins, A. J., Boustani, M., Callahan, C. M., & Hendrie, H. C. (2014). Impact of noncaregiving-related stressors on informal caregiver outcomes. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 29(5), 5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317513518652

- Bakas, T., Jessup, N. M., McLennon, S. M., Habermann, B., Weaver, M. T., & Morrison, G. (2016). Tracking patterns of needs during a telephone follow-up programme for family caregivers of persons with stroke. Disability and Rehabilitation, 38(18), 1780–1790. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1107767

- Cech, D. J., & Martin, S. (2012). Functional movement development across the life span—Elsevier eBook on VitalSource (3rd ed.). Elsevier.

- Charlson, M. E., Pompei, P., Ales, K. L., & MacKenzie, C. R. (1987). A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 40(5), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

- Clark, M. S., & Mills, J. R. (2012). A theory of communal (and exchange) relationships. In Handbook of theories of social psychology, Vol. 2 (pp. 232–250). Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249222.n38

- Counsell, S. R., Callahan, C. M., Buttar, A. B., Clark, D. O., & Frank, K. I. (2006). Geriatric resources for assessment and care of elders (GRACE): A new model of primary care for low-income seniors. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(7), 1136–1141. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00791.x

- Doherty, W. J. (1991). Family theory and family health research: Understanding the family health and illness cycle. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 37, 2423–2428.

- Ferraris, G., Dang, S., Woodford, J., & Hagedoorn, M. (2022). Dyadic interdependence in non-spousal caregiving dyads’ wellbeing: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 882389. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.882389

- Fowler, N. R., Head, K. J., Perkins, A. J., Gao, S., Callahan, C. M., Bakas, T., Suarez, S. D., & Boustani, M. A. (2020). Examining the benefits and harms of Alzheimer’s disease screening for family members of older adults: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 21(1), 202. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-4029-5

- Fowler, N. R., Perkins, A. J., Gao, S., Sachs, G. A., & Boustani, M. A. (2020). Risks and benefits of screening for dementia in primary care: The Indiana University cognitive health outcomes investigation of the comparative effectiveness of dementia screening (IU CHOICE) trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(3), 535–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16247

- Friedman, E. M., Shih, R. A., Langa, K. M., & Hurd, M. D. (2015). US prevalence and predictors of informal caregiving for dementia. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 34(10), 1637–1641. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0510

- Garcia, R. L., Kenny, D. A., & Ledermann, T. (2015). Moderation in the actor–partner interdependence model. Personal Relationships, 22(1), 8–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12060

- Gaynes, B. N., Burns, B. J., Tweed, D. L., & Erickson, P. (2002). Depression and health-related quality of life. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 190(12), 799–806. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-200212000-00001

- Gill, T. M., Zang, E. X., Murphy, T. E., Leo-Summers, L., Gahbauer, E. A., Festa, N., Falvey, J. R., & Han, L. (2021). Association between neighborhood disadvantage and functional well-being in community-living older persons. JAMA Internal Medicine, 181(10), 1297–1304. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.4260

- Golics, C. J., Basra, M. K. A., Finlay, A. Y., & Salek, S. (2013). The impact of disease on family members: A critical aspect of medical care. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 106(10), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076812472616

- Holmes, A. M., & Deb, P. (2003). The effect of chronic illness on the psychological health of family members. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 6(1), 13–22.

- Hsu, K. Y., Cenzer, I., Harrison, K. L., Ritchie, C. S., Waite, L., & Kotwal, A. (2023). In sickness and in health: Loneliness, depression, and role of martial quality among spouses of persons with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 71(11), 3538–3545. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.18520

- Kelley, A. S., & Bollens-Lund, E. (2018). Identifying the population with serious illness: The “denominator” Challenge. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 21(S2), S7–S16. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2017.0548

- Kelley, H. H., Holmes, J. G., Kerr, N. L., Reis, H. T., Rusbult, C. E., & Van Lange, P. A. M. (2003). An atlas of interpersonal situations (pp. xii, 506). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511499845

- Kelley, H. H., & Thibaut, J. W. (1978). Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. Wiley.

- Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis (pp. xix, 458). Guilford Press.

- Kim, Y., Kashy, D. A., Wellisch, D. K., Spillers, R. L., Kaw, C. K., & Smith, T. G. (2008). Quality of life of couples dealing with cancer: Dyadic and individual adjustment among breast and prostate cancer survivors and their spousal caregivers. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 35(2), 230–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-008-9026-y

- Kind, A. J. H., & Buckingham, W. R. (2018). Making neighborhood-disadvantage metrics accessible—The neighborhood Atlas. The New England Journal of Medicine, 378(26), 2456–2458. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1802313

- Kroenke, K., & Spitzer, R. L. (2002). The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32(9), 509–515. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06

- Le, B. M., Impett, E. A., Lemay, E. P., Muise, A., & Tskhay, K. O. (2018). Communal motivation and well-being in interpersonal relationships: An integrative review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 144(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000133

- Liang, M. H., Larson, M. G., Cullen, K. E., & Schwartz, J. A. (1985). Comparative measurement efficiency and sensitivity of five health status instruments for arthritis research. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 28(5), 542–547. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780280513

- Liang, Y., Yang, Y., Yang, T., Li, M., Ruan, Y., Jiang, Y., Huang, Y., & Wang, Y. (2022). Effects of cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms on health-related quality of life in community-dwelling older adults: The mediating role of disability in the activities of daily living and the instrumental activities of daily living. Health Soc Care Community, 30(6), e5848–e5862.

- Löwe, B., Unützer, J., Callahan, C. M., Perkins, A. J., & Kroenke, K. (2004). Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Medical Care, 42(12), 1194–1201. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200412000-00006

- Lyons, K. S., & Lee, C. S. (2018). The theory of dyadic illness management. Journal of Family Nursing, 24(1), 8–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840717745669

- National Center for Health Statistics (US). (2018). Health, United States, 2017: With special feature on mortality. National Center for Health Statistics. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532685/

- Patnode, C. D., Perdue, L. A., Rossom, R. C., Rushkin, M. C., Redmond, N., Thomas, R. G., Lin, J. S. (2020). Screening for cognitive impairment in older adults: An evidence update for the U.S. preventive services task force. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554654/

- Revenson, T. A., Marín-Chollom, A. M., Rundle, A. G., Wisnivesky, J., & Neugut, A. I. (2016). Hey Mr. Sandman: Dyadic effects of anxiety, depressive symptoms and sleep among married couples. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 39(2), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-015-9693-7

- Ribeiro, O., Teixeira, L., Araújo, L., Rodríguez-Blázquez, C., Calderón-Larrañaga, A., & Forjaz, M. J. (2020). Anxiety, depression and quality of life in older adults: Trajectories of influence across age. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 9039. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17239039

- Seibert, T., Schroeder, M. W., Perkins, A. J., Park, S., Batista-Malat, E., Head, K. J., Bakas, T., Boustani, M., & Fowler, N. R. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of older primary care patients and their family members. Journal of Aging Research, 2022, e6909413-8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6909413

- Singh, G. K. (2003). Area deprivation and widening inequalities in US mortality, 1969–1998. American Journal of Public Health, 93(7), 1137–1143. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1137

- Singh, G. K., & Siahpush, M. (2002). Increasing inequalities in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among US adults aged 25–64 years by area socioeconomic status, 1969–1998. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(3), 600–613. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/31.3.600

- Sivertsen, H., Bjørkløf, G. H., Engedal, K., Selbæk, G., & Helvik, A.-S. (2015). Depression and quality of life in older persons: A review. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 40(5–6), 311–339. https://doi.org/10.1159/000437299

- Spillman, B. C., Wolff, J., Freedman, V. A., Kasper, J. D. (2014). Informal caregiving for older Americans: An analysis of the 2011 national study of caregiving. ASPE. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/informal-caregiving-older-americans-analysis-2011-national-study-caregiving

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Stewart, A. L., Hays, R. D., & Ware, J. E. (1988). The MOS short-form general health survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Medical Care, 26(7), 724–735. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007

- United States Census Bureau. (2022). About the American community survey. The United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/about.html

- Ware, J., Snoww, K., Ma, K., & Bg, G. (1993). SF36 health survey: Manual and interpretation guide. Quality Metric, Inc.

- Wetherell, J. L., Thorp, S. R., Patterson, T. L., Golshan, S., Jeste, D. V., & Gatz, M. (2004). Quality of life in geriatric generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 38(3), 305–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2003.09.003

- Wild, B., Eckl, A., Herzog, W., Niehoff, D., Lechner, S., Maatouk, I., Schellberg, D., Brenner, H., Müller, H., & Löwe, B. (2014). Assessing generalized anxiety disorder in elderly people using the GAD-7 and GAD-2 scales: Results of a validation study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(10), 1029–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.076

- Wong, J. S., & Hsieh, N. (2019). Functional status, cognition, and social relationships in dyadic perspective. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74(4), 703–714. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx024

- Wright, J. H., & Basco, M. R. (2006). Psychotherapy for depression in older adults.

- Zahran, H. S., Kobau, R., Moriarty, D. G., Zack, M. M., Holt, J., & Donehoo, R, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2005). Health-related quality of life surveillance—United States, 1993-2002. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries (Washington, D.C.: 2002), 54(4), 1–35.