Abstract

Objectives

This research project investigated how family carers in Norway experienced delivering iCST, their need for supervision and the potential for co-occupation.

Methods

Reflexive thematic analysis was used to understand the experiences of 11 carers using iCST for 8 wk. Three semi-structured interviews were conducted with each participant, including a pre-assessment of caregiver burden and a rating of dementia severity.

Results

Most carers described the manual as self-instructive. Some felt overwhelmed when starting iCST. It was important to plan and individualise the sessions to the specific needs of the person with dementia. After delivering iCST the carers described new insights into the person with dementia’s resources and challenges. Obstacles to doing iCST were related to the context, the manual or to specific challenges linked to the person with dementia or to the carer. Most participants described positive experiences, in which shared interaction, engagement and mastery were common.

Conclusion

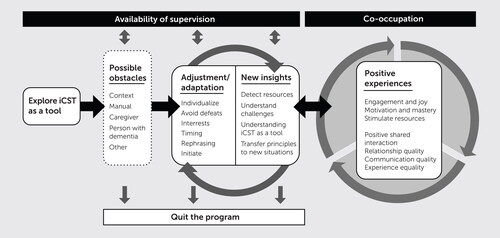

When the carer understands the iCST programme as a tool and adapts it to the specific needs of the person with dementia then co-occupation and positive interactions happen. However, some carers would benefit from supervision and the iCST programme did not address all persons with dementia.

Introduction and background

Cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) is an evidence-based, non-pharmacological and activity-based intervention for people with mild and moderate dementia (Spector et al., Citation2003). CST in groups, first introduced in the UK (Spector et al., Citation2003), demonstrated significant improvements in cognition, communication, social interaction, activities of daily living (ADL) function, depressed mood, anxiety and quality of life for persons with dementia (Woods et al., Citation2023). All formats of CST follow some specific principles allowing the therapist or carer to adapt the materials and sessions to the interests and needs of the person with dementia. Thus, the specific sessions in the manual should be omitted if they clearly are not in the persons interest or cannot be enjoyable or meaningful. This puts a responsibility on the therapist or carer for adapting the content of the manual to the specific person, and requires knowledge of dementia, the specific person, and the principles.

The group programme consists of 14 group sessions delivered twice a week. It is recommended by NICE guidelines (NICE, Citation2018) and the Norwegian Guidelines for Dementia Care (Norwegian Directorate of Health, Citation2022). Unfortunately, the group format of CST may not be suitable or accessible for all due to: sensory impairment; communication challenges; mobility problems; living where group CST is not offered; or a personal preference for not attending group activities (Orrell et al., Citation2017). To reach more people with dementia, individual CST (iCST), a home-based, one-to-one, carer-delivered intervention was developed (Yates et al., Citation2015) and presented in a manual for carers (Making a difference 3; Yates et al., Citation2019). iCST was developed through thoroughly iterative processes including family caregivers, people with dementia, and professionals familiar with CST, as described in Yates et al. (Citation2015). The manual is now translated and adapted to a Norwegian cultural context (Yates et al., Citation2021).

The iCST manual consists of 75 sessions with a variety of activities, such as crosswords, word and number games, pictures to categorise, creative activities and physical games. The introduction contains the key principles for delivering iCST, it highlights the purpose of the programme and how it can be individualised. The difficulty level of each session can be adapted (levels A and B). Each session is supplemented by suggested questions to challenge associations and thinking, and includes colour photos or visual support. The main aim of the iCST manual is to assist carers with enjoyable activities that may stimulate cognition and reduce inactivity for people with dementia. The iCST manual is built on the best evidence for increasing quality of life, improving memory and other cognitive abilities, and make a difference for people with dementia (Yates et al., Citation2019).

The effects of iCST on cognition and quality of life is not as strongly supported as for group CST (Woods et al., Citation2023), but treatment adherence in the largest randomised control trial (RCT; N = 356) to date was quite low (Orrell et al., Citation2017). Two smaller RCTs found a significant effect of iCST on cognition and quality of life in the person with dementia (Gibbor, Forde, et al., Citation2021; Silva et al., Citation2021). Positive effects were found on caregivers’ well-being and quality of life and on their relationship with the person with dementia (Orgeta et al., Citation2015; Orrell et al., Citation2017). Carers have reported positive outcomes for the person with dementia, such as improved spontaneous speech, interactions and moods, and being more willing to partake in social settings (Silva et al., Citation2021). Carer-delivered cognitive stimulation interventions can be stimulating and enjoyable, providing opportunities to engage in pleasurable and mentally stimulating activities together (Leung, Orgeta, et al., Citation2017).

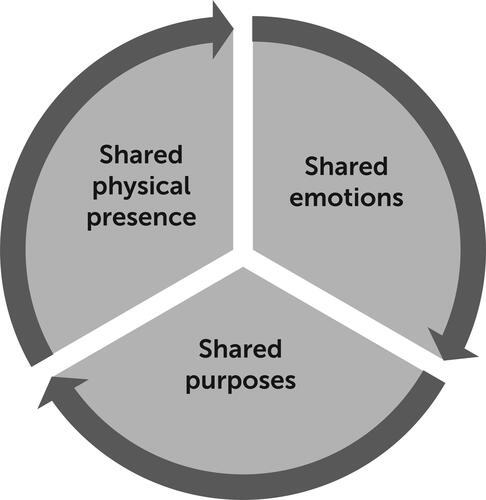

Occupational science (OS), with its pluralistic epistemology, systematically studies humans as occupational beings. One major value of OS is the relation between occupational engagement (the dynamic process of a person performing an activity in a specific environment) and the healthfulness of the person. OS seems a suitable theoretical approach to explore iCST because it seeks to understand the complexity of dynamic interrelations and how this influences health and well-being (Wilcock & Hocking, Citation2015). To participate in meaningful occupation is essential for people with dementia to maintain cognitive health. People with dementia are often at risk of being occupationally deprived due to taken-for-granted prejudices about being vulnerable and no longer cognitively capable (Laliberte Rudman, Citation2012). Such prejudices may result in ignorance of an individual’s resources and occupational injustice.Footnote1 With family caregivers delivering iCST training, the person with dementia has access to meaningful activity, based on one-to-one contact and performing an activity together, which can be referred to as co-occupation. Although there is, as yet, no consensus on a definition of co-occupation, it does relate to interactions between two or more persons, which are mutually responsive and are emotionally and intentionally shared experiences (; Pickens & Pizur-Barnekow, Citation2009, p. 153).

Figure 1. Co-occupation enables shared presence, emotion and purpose (from Pickens & Pizur-Barnekow, Citation2009, p. 153)

The intentionality of an occupation means defining a mutual goal and understanding each other’s roles and intentions (Pickens & Pizur-Barnekow, Citation2009). We believe the intention of iCST is to serve as a mutual, purposive action that gives participants an opportunity to share a physical and emotional presence that enables an experience of meaningfulness for the dyad. Thus, if a carer follows these intentions, iCST could facilitate co-occupation. Although family carers are at risk of burnout and depression (Cheng, Citation2017), they may experience delivering iCST training as a meaningful activity for both parties.

As part of launching the iCST manual in Norway, we wanted to explore the following questions:

How do family carers experience the use and utility of the manual for iCST with their family member with dementia?

Do the family caregivers need supervision before or during iCST delivery?

How can iCST facilitate co-occupation and shared meaning?

We conducted qualitative interviews to answer these questions, which allowed us to assess lived experiences and to gather rich descriptions (Smith & Fieldsend, Citation2021; Terry et al., Citation2017).

Method

Translating and culturally adapting the manual

The original CST-material has been developed through iterative processes including generating knowledge through research, and collaborating with stakeholders, integrating this information with theory and empirical and clinical knowledge (Aguirre, Spector and Orrell, Citation2014). The three translators of the Norwegian manual (T. Holthe, R. Weum & T. K. Rønqvist) are occupational therapists and neuropsychologist, respectively, with experiences of working with group CST, and long clinical practice of working with people with dementia. The licence of the manual with the publishing house specified that a Norwegian version must address the same topics and expressions, and any changes or cultural adaptations from the original version were discussed with and approved by the publisher. We sought the caregivers’ opinions on the manual through this project.

Participants and inclusion criteria

We recruited a purposive sample of family carers to try out the manual using the following inclusion criteria:

caring for a person with mild or moderate dementia at home

interested in trying the iCST manual

willing to give three interviews by telephone, video call or in person.

Recruitment procedure

The participants were recruited through the Norwegian Alzheimer’s association and community memory teams in Viken county and the outpatient clinic at NKS Olaviken Gerontopsychiatric hospital. Family carers volunteering for the project received a formal invitation letter with an informed consent form for them to sign and return to the project leader. After receiving the consent, the manual was sent to participants and interviews were scheduled.

Ethical approval and data management was assessed and granted by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (ID 463683).Footnote2

Data collection

Data was collected through semi-structured interviews (Smith & Fieldsend, Citation2021) at three points: before using the manual (T0); three weeks into the trial (T1); and after eight weeks of the trial (T2).

Two standardised questionnaires were included at T0: the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR; Hughes et al., Citation1982); and the Relatives’ Stress Scale, (RSS; Greene et al., Citation1982). Additionally, sociodemographic data and participants’ expectations of the iCST programme were aquired. At T1 and T2 we conducted semi-structured interviews on the manual’s use and utility. A flexible interview guide was developed by the research team to allow participants to bring up topics they found important (Smith & Fieldsend, Citation2021). After having carried out two T2 interviews, questions exploring relational experiences during iCST were added, inspired by Leung, Yates et al. (Citation2017). The interview guide is available in the supplementary material.

Analysis

A thematic analysis allows for a flexible approach to analysing data with different theoretical underpinnings (Terry et al., Citation2017). We used an interpretative and phenomenological approach to explore perceptions and understanding of the experience, including its social and psychological aspects (Smith & Fieldsend, Citation2021). The analyses investigated similarities and differences across family carer experiences of providing iCST, using reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) to develop both semantic descriptions and latent themes from the interviews (Braun et al., Citation2019; Terry et al., Citation2017). The semantic themes were related to the first research questions about the use and utility of the manual, and the latent themes were related to assessing the possibility for co-occupation during iCST.

The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Each author interviewed and transcribed one third of the audio files. Before starting the analysis we wrote down and discussed our pre-understanding of dementia and iCST and our expectations of the results in order to be transparent about the influence this could have on the analysis (Smith & Fieldsend, Citation2021). Each author made reflective notes during data collection on their own interpretations and preconceptions before, during and after the interviews (Braun et al., Citation2019).

The analysis was conducted using NVivo to manage the data (QSR International Pty Ltd., Citation2020). The RTA followed the six steps of Braun et al. (Citation2019). First, all authors read all transcripts and made initial notes to familiarise themselves with the data. We then sorted the data under four main topics (feasibility, delivery, positive and negative experiences) related to our research questions, using a deductive approach. After which, each author read one third of the interview transcripts by another researcher and started to generate initial codes and preliminary themes related to the four topics, using an inductive approach. Next, we discussed notes, interpretations of text segments and initial codes, to develop candidate themes. Relevant data from all participants were coded and systematised into the different constructed themes and sub-themes. Theme descriptions were written as part of the coding and review process and each theme was discussed against the research questions and the overall data set to test their validity and ability to capture a meaningful pattern. A thematic map of the findings was drafted, discussed and revised. This map was a visual support for our interpretation of the findings and for how the phenomena could be connected (Braun et al., Citation2019; Smith & Fieldsend, Citation2021). The results were also analysed in regards of our interpretation of the overall utility of the program for each participant, and the relation between the described utility and scores on the CDR and RSS.

The codes, interpretations and themes were repeatedly discussed by the team and checked against each other and the original data set until their definitions and revisions were clear and provided a coherent conceptualisation of the data (Braun et al., Citation2019). The interviews were re-read several times to cross-check that any new themes or patterns discovered remained close to the overall data set at later stages in the analysis. We also looked for competing interpretations in the data set. The themes were described using words close to participant descriptions, as is recommended in phenomenological approaches (Smith & Fieldsend, Citation2021). Quotes illustrating the themes were identified from the coded material, to increase transparency and to allow the reader to assess the validity of the themes (Smith & Fieldsend, Citation2021). Finally, a theoretical model based on the thematic map was created, to illustrate how the themes were related.

Results

Participants

Eleven participants volunteered for the project. Demographic data is presented in . Two participants withdrew from the study after the T1 interview due to a high burden of care (RSS 48 for both) and to the person with dementia being less motivated for iCST. All available interview data were included in the final analysis. Quotes from the participants are marked with their participant number (P1–P11) to increase transparency without revealing the carer’s identity.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

Expectations before using the manual

At the first interview (T0) most participants described positive expectations of the iCST programme. ‘I feel open-minded, and I think this will be exciting’ (P6). ‘This is going to be our project’ (P7). Some were more hesitant, pointing out that iCST was new to them and they did not know what to expect. ‘No [specific expectations], because I don’t know what it is, maybe a board game or whatever, I have no clue…’ (P3). Several participants expressed a wish to delay the progression of the dementia by providing stimulating tasks. ‘We know there is no cure, but we’ll do all we can to delay this [decline] as long as possible’ (P9). Most carers also talked about themselves and the person with dementia as one unit (‘we’ or ‘us’), as one emphasised. ‘I must ensure that it continues to be “the two of us” like before, not “me” and “him over there”’ (P7). They hoped that iCST would provide positive and enjoyable activities. ‘My primary goal is to find activities my spouse can enjoy’ (P4).

Experiences after having used the iCST manual

Number of completed sessions at T1 (after 3 wk) were 10 on average (range 6–12, 3 participants could not specify a number of sessions). Average point for T2 was 10 wk (range 7–16), with some delays due to holidays, hospitalisation, or lack of time to prioritise iCST. Completed sessions at T2 were 32 (range 12–70, 1 could not specify a number of sessions).

Six carers described iCST as beneficial overall, three described some positive experiences and two described very little or no benefits from using the iCST programme. We did not find any systematic relationship between RSS, CDR and the reported utility of the iCST-program. An overview of the findings is provided in .

Table 2. Overview of topics, themes and sub-themes.

Delivering iCST

Under the topic ‘Delivering iCST’ the data was structured around three themes: family carers’ first impression of the manual; planning for a successful session; and revealing new insights.

Family carers’ first impression of the manual

A self-instructive manual

Most participants found the manual self-instructive. They described the introduction as easy to understand, and the introductory chapters as a useful description of a tool they could try. Further, the key principles were understandable to most participants.

I would say the manual is clear and easy to understand. And it’s not complicated to get started with it. It’s something that everyone should be able to master. (P4)

The participants appreciated having many pictures and multiple sessions to choose from, which made it easier to find something that engaged the person with dementia. All sessions had levels A and B, and most participants chose the level related to their interests. Three always chose level B, as they found level A too easy. A few reported that a spiral binding made the book easier to lay open so both could have a look.

Starting iCST is overwhelming

Some participants found the manual overwhelming, saying that the introduction provided too much information. They felt uncertain about what was expected of them when delivering the sessions. Two participants described the manual as too big and heavy, with text that was too much and too complex. They felt the manual was rigid and requested a commitment that was hard for them to meet.

I felt it was so much, so if I should dare to begin using these tasks in a good kind of pedagogical way, I found it very demanding. (P3)

Planning for a successful session

Prepare to individualise the programme

All participants agreed that it was important to prepare for the sessions and to adapt them to the person with dementia. Eight reported that the preparations were quite easy by reading the manual, while three found them challenging. Preparations included thinking about how to use the key principles and finding the right equipment. Individualising the sessions implied skipping those that seemed too difficult and adapting the level of the task to make sure the person with dementia could master it. They also stressed avoiding defeat, including adapting the task if the person had a sensory impairment. Tailoring the sessions to the person’s interests was described as an important process to increase engagement.

I know he is interested in words and language and so on, and then I think it is important to do something you feel like you succeed with. (P1)

Adaptation also included rephrasing instructions to make them easier to understand, finding the right way to introduce the task and which questions to ask.

I feel [the preparation] is very straightforward, but I do not complete the instructions for each task exactly as it is written. I try to understand how it could be completed, and then I ask questions based on how I know [the person with dementia] can answer. So, I adjust and adapt all the time. (P3)

Finding the right time to initiate iCST

Timing of the iCST sessions was stressed by most participants. It was important to deliver iCST when the person’s energy and attention levels were optimal. If the person was tired, confused or had other appointments that day, the iCST session was likely to fail. Family carers also agreed that doing sessions before 1 pm worked best. Some reported that persons with dementia easily got tired doing iCST tasks and had low stamina. A 30-minute session could be too long for some and was shortened.

Yes, you must be a bit disciplined then! You must make a choice! That this [iCST] is something that we are going to do! … It must be a day when he is IN on it. You know when the best time is. And then, you catch yourself in the neck and … you cannot say: oh no, I am not up for it today. (P11)

Preparing and adapting the sessions was a premise for success. Several participants wanted more explanation of a task’s purpose and which cognitive functions were stimulated by each session, to help with preparations. One example of individualisation was a carer who offered their spouse with dementia a look through the manual to select what caught their interest, to keep them motivated. Having a successful session was motivation for getting involved in further sessions. It was paramount that the carer initiated and continued the iCST as the person with dementia mostly did not initiate it themselves.

Revealing new insights

Resources and challenges were discovered

Delivering iCST to a family member with dementia gave new insights into how the condition was influencing the person. Most participants said they had detected resources in their family member which gave them joy, hope and motivation. They described how they could understand dementia better, and how to facilitate activities with the right questions and approaches. The iCST programme taught family carers how to reveal these resources.

I was kind of pleasantly surprised over how much I could ‘bring alive’ in him, for example, when we started with the family tree … It gave me a ‘WOW experience’ because everything was not lost! You must use certain approaches to reveal it … using this manual has been very inspiring. (P11)

Moreover, some participants got insights into which skills the person had lost due to dementia. This led to a better understanding of the challenges that person faced.

And I get more insight into what he may be struggling with – for example words – words that he knows well, but finding them, and then saying the right word … And then I may see his disability and get more insight into it. (P1)

A new tool for the carer

Many participants demonstrated an understanding of how to use iCST and how to adapt the activities for the person with dementia. They described how the manual inspired them to develop skills.

Borrowing skills from that book, and mimicking them, and making them your own … so that you own them and pass them on. That is what has become part of the effect for me (P2)

Transferability of iCST principles

Many participants described how such insights could inspire them to transfer the principles to other contexts, for example by using stimulating tasks during the day or learning how to phrase questions and introduce different topics. They also described how to avoid confronting the person with dementia with their shortcomings.

I have attained a better understanding of the disease, and that [person with dementia] can be active even if he has got dementia. And now I know how to bring out his resources. (P1)

Positive experiences with iCST

All the participants described at least one positive encounter for the person with dementia or for the dyad during iCST.

Positive experiences for person with dementia

iCST is engaging and fun

Most participants described how the person with dementia had positive experiences with iCST. Engagement and joy were described by many, where using the manual triggered conversations that might not have taken place without the programme. Several reported that the person with dementia became more talkative and engaged.

Yes, music and word games [sessions 14 and 42] – he was very talkative during these sessions. And one of the things that changed [after the dementia diagnosis] is that he is very silent. But here we found questions that facilitated conversation. (P7)

A sense of mastery and motivation

Many carers described how the sessions facilitated motivation and mastery when they were connected to the person’s interests.

It is nice that the manual lets you choose topics of interest, which can be adapted to the specific person. It gives a sense of mastery, and it makes you want to participate here and now, and to participate in the next session (P2)

Activities that engaged often gave more responses, cheerfulness and a motivation to continue taking part in iCST. One participant reported that, after the session finished, the person with dementia engaged independently with the family tree task.

The first one [session 1] was great for my husband. I planned for 30–40 minutes, but he wanted to continue alone. He continued for over three hours. He kept on working, looked at pictures and commented on what they depicted. (P1)

When the tasks stimulated remaining resources, the person expressed mastery. This was described as a positive experience for the person with dementia.

And then we discussed news. Yes, he is really updated on news and has a lot of knowledge about it. Maybe even more than me at times. So, it was an interesting conversation with a lot of coping involved. (P6)

Positive experiences for the dyad

Shared interaction

The participants described how iCST can become a tool for conversations, structuring the dyad’s interaction and stimulating language. All participants described iCST as enabling a positive shared interaction to some extent. Several described how the sessions contributed to positive experiences for the person with dementia, which again made the carer feel good.

It does something to us to have an interaction, which we both experience as positive. As well as the regularity … So, I really think this is good. … Just to take the time to do something different than we usually do. … A shared experience – something we can talk about later. (P2)

The dyads experienced joy together, they laughed together. For some, iCST even strengthened a companionship in the dyad.

Yes, we laugh and share humour in the sessions. We laugh spontaneously because it just becomes fun. (P1)

Eight participants also described positive relationship qualities during iCST.

The manual is positive for our relationship because we spend time together, doing something positive. … The book becomes a facilitator for these [interactions] (P1)

Half the participants described iCST as a project for the dyad together and underlined the importance of equality between them during sessions.

Well, she [person with dementia] is very concerned about us being equal. And, I have to answer the questions as well. I think it is very important in such a setting that we try to participate as equals. It should be communication between us, not just me asking questions with her answering them. We need to do this together. Because the imbalance is there anyway, as it is now, so it’s a good idea to be able to create that reciprocity or balance where you can. (P4)

Learning to communicate in a new way

New insights also included how to phrase a question or introduce a topic. Several reported a change in the quality of communication after using iCST.

I think I have become cleverer at asking ‘What do you think about …’ and ‘What do you think your mother would say if she saw you during this activity?’ And then we had different reflective answers, and it was interesting because we had another type of communication. (P1)

When he is in the mood, I really think it [the iCST programme] is quite enjoyable. It is! And it is this type of contact that you miss in daily interactions, which often happens when people have dementia … you get a hope? I really think so! … I am happy when we have completed a session together. I am happy for every conversation we can have (P3)

Obstacles to iCST

All participants encountered different obstacles during the project, related to the iCST manual’s materials and procedures, to uncertainty in the carer, and to the interests and motivation of the person with dementia.

Obstacles related to context or manual

Lack of time

Most participants described iCST as time consuming. For some it was too hard to find time in a busy schedule between work and leisure, or because they had no breaks in the daily routine to prepare the sessions. This lack of time to prepare for iCST meant they regarded it as too time-consuming and demanding.

I didn’t have time for preparations because there were other tasks to be done – after work and after food, plus plus … so we didn’t get to sit down until 6 pm (P10)

A few participants also found it demanding to find the materials and equipment requested by the manual.

Struggling to adapt materials and procedures

All participants described a process of adapting materials and procedures, and a few felt the content of the manual was too difficult to adapt to the person with dementia. Some pictures were too small. Some tasks were too easy or too difficult. A particular obstacle was visual impairment, as was the use of expressive language, since the manual required dialogue.

I feel that it is difficult to have a proper conversation because he doesn’t respond much to the questions and … well, he finds it very difficult to express an opinion and to say something. He can’t find the words … so reasoning and drawing conclusions made many of the tasks very complicated (P10)

iCST feels like a test

Some participants described how some sessions were experienced as a test by the person with dementia, rather than as a shared stimulating activity. Some tasks were experienced as checking whether they could answer correctly, which raised concerns about giving right or wrong answers. Some dyads experienced delivering iCST as though it was a teacher–student relationship, which was described as challenging.

He didn’t quite understand the questions, for example ‘which of these is not one of the seven deadly sins?’ He didn’t get it. … And then I went on: ‘is vanity … is this something that can develop too far?’ But then he felt this was a ‘test’ (P7)

Obstacles related to family carer

Negative beliefs about dementia

Some obstacles to using the iCST manual were related to the family carer. A few participants showed attitudes or beliefs towards dementia that prevented them from seeing any utility in iCST.

There’s no point for him to learn anything new now … Now we must take care of what is [left], as well as possible! There are nice words [in the key principles], but I don’t know if it will be too much – that it will be a bit too [demanding] for him (P3)

Uncomfortable in role of iCST deliverer

Some carers disliked their role when delivering iCST. They felt they had to guide the person too much, and always be in charge.

And the one question about ‘What is the message of the advertisements?’… [He answered:] ‘Buy more and be happy!’ Then I asked, is that the only message? And I may have sounded like I was asking: ‘are you sure you’re answering correctly now?’ like I was checking whether the answer is correct (P2)

Some described changing the teacher–student-like relationship to more equal participation in the tasks. Others could not overcome this obstacle.

So, I get the manual, and then he … ‘Oh … do I have to?’ It’s like a child being forced to do homework – right? (P10)

Uncertainty about delivering iCST

Some participants felt uncertain about delivering iCST. This could be due to previous roles in the relationship that had been challenging, but also to how much they should push the person with dementia, and whether pushing was part of the individual adaptation. For instance, one participant experienced the person with dementia quickly tiring during sessions and asked:

How much should I push? So – what should I have done here? Should I have just completed the introduction and then finished up and said: ‘I don’t think anything good will come of this?’ And, what [happens] if I am pushing too hard? (P6)

Obstacles related to person with dementia

This topic is closely related to the topic of planning a successful session. Participants described adjusting and adaptation for the individual they cared for.

Sensory and language impairment

Some impairments, in particular vision, hearing and language, were obstacles to benefiting from the programme, and could result in rejecting iCST.

That was difficult [to sort out]; eggs, bacon and tomatoes – it might be because of his trouble with vision (P1)

Lack of mastery

Several of the persons with dementia expressed signs of defeat if they felt they did not master the session or that they were being tested. This could lead to negative associations with iCST for the person with dementia. As one carer said: ‘He is very reluctant to do things that he is not sure he can manage properly.’ (P2)

Resistance to iCST

Several sources of resistance were identified by the carers. Some participants found the iCST materials too complicated and demanding for the person with dementia, which led them to resist participating in the sessions. It was important for the session’s tasks or topics to be of interest to the person with dementia.

I think that many of the tasks [in iCST] are quite demanding. You must think! The tasks require you to see similarities and differences, and you have to prefer one thing over another … Well, it’s quite a challenge, and if it doesn’t ring any bells and you’re not interested in what’s being asked about then … eh … then it’s not something you get excited about or think about (P10)

Daily fluctuations in mood could also cause the person with dementia to refuse to participate in a session.

And when I grabbed it [the manual] he asked: ‘what is this?’ Then I said, ‘but now we’re going to …’ He replied ‘no’ – and that he did not want to do this. He was not demented, he said (P2)

Fluctuations in concentration and tiredness

Some persons with dementia became easily tired, which prevented them from continuing full length sessions. For some, their level of concentration fluctuated from day to day.

I think this has something to do with time … 25 minutes … And then, suddenly he is tired! (P8)

Discussion

This study explored the experiences of family carers using the Norwegian iCST manual with their family member with mild or moderate dementia to learn: whether carers could use the manual without supervision; if obstacles were met during programme delivery; and if iCST positively could influence the the dyad’s relationship and facilitate co-occupation. The overall findings and relations between themes are presented in .

As illustrates, iCST is a potential tool for caregivers who want to provide cognitive stimulation to a family member living with dementia. describes the dynamic process and possible obstacles that must be addressed for the tool to be fruitful and become a co-occupation with shared intentions, purposes and emotions.

There were several challenges to using the manual as intended, related to the context of the dyad, the manual itself, the carer’s resources, and to particular challenges for the person with dementia. Many carers overcame obstacles during the process of learning to use iCST. However, it was not possible to adjust for all potential other obstacles and, in such cases, iCST was not a positive experience and the dyad left the programme.

Strategies to overcome obstacles could be: individualising the content; tailoring sessions to a person’s interests to increase engagement and mastery; rephrasing explanations to match the needs of the person with dementia; and ensuring timely delivery of sessions. It was important that iCST was not experienced as a test. Is it possible for family caregivers to use such strategies without training or supervision? Leung, Yates et al. (Citation2017) reported that family carers experienced difficulties in completing sessions as planned and suggested that involving others in delivering the programme could serve as an extra support that may improve adherence. Involving a support person to deliver iCST, might be positive for the person with dementia. However, as our study finds, family carers would then miss out on new insights into the consequences of dementia or opportunities for co-occupation.

There were variations in experiences of delivering iCST. Although participants had hopes for participating in a mutual project, having regular quality time and an opportunity to share emotions and meaning, it was not quite as easy to carry it through. One important premise for iCST’s success was the timing of the sessions. It was best to do the sessions early (before 1 pm) and when the person with dementia felt up to it. Some participants said that their spouses with dementia felt the iCST programme was a test. When they could not answer a question, they felt defeated and confronted with their challenges. The person with dementia became sad, while the family carer shared the moment and the feelings. Such experiences became a threat to continuing the programme.

Delivering iCST gave caregivers a new understanding of three aspects: insights in resources and challenges for the person with dementia; how the manual could serve as a tool for a shared interaction; and how the key principles could be transferred to other activities in daily life. Such insights encouraged an ongoing adaptation, in a circular process. The carers who managed to use the iCST manual in a flexible way and tailored the tasks to the individual, were able to share a physical presence and a mutual intention and emotion. Through this, they experienced positive outcomes for both the person with dementia and the dyad. We believe they experienced co-occupation.

The increased understanding of the difficulties experienced by their family member with dementia is reported in earlier research on iCST (Orrell et al., Citation2017). Other qualitative work has reported that family carers delivering iCST have found the manual a useful tool for offering pleasurable activities that may facilitate communication and enhance the quality of the relationship (Leung, Yates, et al., Citation2017; Orrell et al., Citation2017).

Even if it is still uncertain whether iCST has an effect on cognition or quality of life for people with dementia, family carers providing iCST have reported improved quality of the relationship and their own quality of life (Orrell et al., Citation2017). Our study finds that the iCST manual supported the carer in identifying suitable strategies to provide iCST and to improve the quality of the relationship with their family member, in line with Silva et al., Citation2021.

A literature review of qualitative studies on both group-based CST and iCST for people with dementia concluded that taking part in CST encouraged concentration, reflection and awareness in people with dementia, and supported learning and helped the person to be present, here and now (Gibbor, Yates, et al., Citation2021). This is in line with our findings for those who reported successful use of the manual.

However, persons with dementia are dependent upon others for access to such training and if they have language, vision or hearing impairments, it is more challenging for the family carer to carry out the programme. Our findings suggest the programme easily becomes too demanding in such cases.

Moreover, some carers said that the person with dementia would have benefited more if they had started the programme a year earlier. Those who dropped out of the study were also those with the highest caregiver burden, which may have made the caregiver to exhausted to initiate iCST. However, the dropouts did report some utility of the program in the first interview. According to Woods et al. (Citation2023), group CST has most benefits for people with mild dementia. So, one may ask, when is the right time to introduce iCST?

illustrates how supervision, if offered, could have helped some carers to overcome obstacles and continue to use the programme. Although only two participants explicitly expressed a need for supervision, several described situations in which they struggled with adapting and preparing sessions to the specific needs of the person with dementia. One example is those dyads who were eager to learn whether they had answered correctly. Although there is a section with ‘answers’ in the back of the manual, the programme strongly encourages seeking opinion rather than fact (Principle 4). We believe timely supervision may help the family carer to create a dialogue and avoid ending up checking for right or wrong answers.

In earlier studies carers had received training before initiating iCST (Leung, Yates et al., Citation2017; Silva et al., Citation2021). In this study, more than half the family carers managed to use the manual without any guidance. However, some training and supervision might have helped more carers overcome some of the obstacles described. Sessions that were not prepared for were reported as failing easily, but lack of time to prepare was also commonly described by our participants. Some carers reported a significant burden of care (RSS) and of working long days and then initiating iCST in the evening became too exhausting for both parties. In such circumstances, including a support person or a professional to deliver iCST, as suggested in Gibbor, Forde et al. (Citation2021), could have been an option. Professionals delivering iCST seem to increase programme adherence, which has been a problem in most trials on iCST to date (Silva et al., Citation2021; Orrell et al., Citation2017). The standard recommends delivering iCST 3 times a week for 20 min. Our participants revealed that the frequency of iCST sessions varied between 7 and 16 during the first 3 wk (at T1), and between 12 and 70 after 8 wk (at T2). According to the recommended frequency, it should have been 9 sessions by T1 and 24 by T2. Studies assessing CST have suggested a dose-response relationship (i.e. Gibbor, Forde et al., Citation2021). Lack of adherence to the programme influences the effect of iCST, but the most common obstacles reported by our participants have a large impact on adherence, such as: lack of time; carer uncertainty about delivering iCST; lack of mastery in the person with dementia; resistance to the programme; and fluctuations in mood and concentration.

Methodological considerations

The main limitation to this study is the homogeneity of the group of participants, who came from a similar cultural and sociodemographic background. The sample was relatively small, but several interviews with the same participants made it possible to analyse the material in depth. Several participants who described iCST as beneficial had worked in health care or education. Recruiting a more heterogeneous sample would have increased the transferability of our findings to other contexts. In line with all other quantitative and qualitative research projects published on iCST the adherence was not as frequent as recommended in the manual. We were not able to interview the two participants who dropped out and may have overlooked some obstacles they would have described if they had agreed to participate in the last interview (T2). In hindsight it could have been informative to know the number of years the caregivers had cared for the person with dementia to see if this could have influenced how iCST was delivered.

Some participants were interviewed with the person with dementia in the room. This may have led to carers speaking less freely about iCST topics in order not to promote negative emotions in the person they cared for.

Most participants described an expectation prior to participation of using iCST to slow the degenerative development of dementia. This may have led to a moral duty to use the iCST manual that may have overwhelmed some participants. When facing a disease without a cure, it is important not to induce unrealistic hopes that may increase the caregiver’s burden or contribute to a bad conscience if you fail to use the programme.

Implications

Our findings contribute to a better understanding of iCST as a tool for co-occupation, with limitations and possibilities described in our thematic model (). This could bring forth new hypotheses about how iCST could be adjusted and adapted to contribute to well-being in carers and persons with dementia. It seemed the key components for iCST to be successful when the aim is co-occupation are 1) for the carer to become familiar with the key principles and tailor the tasks to the interests and cognitive level of the person with dementia; 2) participate in the program as equals and avoid it becoming a test; 3) be flexible about timing and adapt the material to sensory impairments or other specific needs for the person with dementia; 4) make sure the program is experienced as engaging and fun. Future research could develop training programmes and test different supervision models for carers to achieve co-occupation during iCST.

Conclusion

The iCST programme and manual was well received by 8 of the 11 participants and seemed to be a valuable tool for many carers who wanted to engage in the everyday life of their family member with mild or moderate dementia, and to create opportunities for co-occupation. Co-occupation is both an aim and a process to maintain shared meaningful activities and events. The material may be used without any specific training, but some carers seem to need guidance or supervision to deliver iCST as recommended. Researchers from the UK recommend training in delivering iCST. In Norway, we consider making video tutorials on the key principles and establishing a chat line for family carers who have questions regarding iCST.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (34.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants for sharing their valuable experiences with us during this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Occupational justice means that all citizens should have fair access to occupations they need to accomplish everyday living (Wilcock & Hocking, Citation2015, p. 414).

2 The project was reported to the Norwegian Centre for Research Data – NSD and Regional Ethical Committee – REK, February 2022. REK found the project to be outside the field of health research, thus no approval is required.

References

- Aguirre, E., Spector, A., & Orrell, M. (2014). Guidelines for adapting cognitive stimulation therapy to other cultures. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 9, 1003–1007. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S61849

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences (pp. 843–860). Springer. https://url12.mailanyone.net/scanner?m=1q6piN-00069v-63&d=4%7Cmail/90/1686130800/1q6piN-00069v-63%7Cin12e%7C57e1b682%7C28538618%7C14196068%7C6480517BF16B7BEFFEDE7F1BD173E36D&o=/phto%3A/dts0ri.1/1.og-/00878979501–5211-301_4&s=uc1OC7aL1m-mXRI7Oucn6L4y4Rk

- Cheng, S. T. (2017). Dementia caregiver burden: A research update and critical analysis. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(9), 64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0818-2

- Gibbor, L., Forde, L., Yates, L., Orfanos, S., Komodromos, C., Page, H., Harvey, K., & Spector, A. (2021). A feasibility randomised control trial of individual cognitive stimulation therapy for dementia: Impact on cognition, quality of life and positive psychology. Aging & Mental Health, 25(6), 999–1007. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1747048

- Gibbor, L., Yates, L., Volkmer, A., & Spector, A. (2021). Cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) for dementia: A systematic review of qualitative research. Aging & Mental Health, 25(6), 980–990. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1746741

- Greene, J. G., Smith, R., Gardiner, M., & Timbury, G. C. (1982). Measuring behavioural disturbance of elderly demented patients in the community and its effects on relatives: A factor analytic study. Age and Ageing, 11(2), 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/11.2.121

- Hughes, C. P., Berg, L., Danziger, W. L., Coben, L. A., & Martin, R. L. (1982). A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 140(6), 566–572. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.140.6.566

- Laliberte Rudman, D. (2012). Governing through occupation: Shaping expectations and possibilities. In Whiteford & Hocking (Eds.), Occupational Science. Society, Inclusion, Participation. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Leung, P., Orgeta, V., & Orrell, M. (2017). The effects on carer well-being of carer involvement in cognition-based interventions for people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(4), 372–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4654

- Leung, P., Yates, L., Orgeta, V., Hamidi, F., & Orrell, M. (2017). The experiences of people with dementia and their carers participating in individual cognitive stimulation therapy. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(12), e34–e42. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4648

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2018). Dementia: Assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. NICE guideline [NG97].

- Norwegian Directorate of Health. (2022). Demens. Nasjonal faglig retningslinje. [Dementia, National guidelines] Oslo, Norway. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/demens

- Orgeta, V., Leung, P., Yates, L., Kang, S., Hoare, Z., Henderson, C., Whitaker, C., Burns, A., Knapp, M., Leroi, I., Moniz-Cook, E. D., Pearson, S., Simpson, S., Spector, A., Roberts, S., Russell, I. T., de Waal, H., Woods, R. T., & Orrell, M. (2015). Individual cognitive stimulation therapy for dementia: A clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England), 19(64), 1–108. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta19640

- Orrell, M., Yates, L., Leung, P., Kang, S., Hoare, Z., Whitaker, C., Burns, A., Knapp, M., Leroi, I., Moniz-Cook, E., Pearson, S., Simpson, S., Spector, A., Roberts, S., Russell, I., de Waal, H., Woods, R. T., & Orgeta, V. (2017). The impact of individual Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (iCST) on cognition, quality of life, caregiver health, and family relationships in dementia: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS Medicine, 14(3), e1002269. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002269

- Pickens, N. D., & Pizur-Barnekow, K. (2009). Co-occupation: Extending the dialogue. Journal of Occupational Science, 16(3), 151–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2009.9686656

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2020). NVivo (released in March 2020). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home.

- Silva, R., Bobrowicz-Campos, E., Santos-Costa, P., Cruz, A. R., & Apóstolo, J. (2021). A Home-Based Individual Cognitive Stimulation Program for Older Adults With Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 741955. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.741955

- Smith, J. A., & Fieldsend, M. (2021). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In P. M. Camic (Ed.), Qualitative research in psychology: Expanding perspectives in methodology and design (pp. 147–166). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000252-008

- Spector, A., Thorgrimsen, L., Woods, B., Royan, L., Davies, S., Butterworth, M., & Orrell, M. (2003). Efficacy of an evidence-based cognitive stimulation therapy programme for people with dementia: Randomised Controlled Trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 183(3), 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.183.3.248

- Terry, G., Braun, V., Hayfield, N., & Clarke, V. (2017). Thematic Analysis. In C. Willig, & Rogers, W. (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology (pp. 17–37). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Ulstein, I., Wyller, T. B., & Engedal, K. (2007). High score on the Relative Stress Scale, a marker of possible psychiatric disorder in family carers of patients with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(3), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1660

- Wilcock, A. A., & Hocking, C. (2015). An occupational perspective of health (3rd ed.). Slack.

- Woods, B., Rai, H. K., Elliott, E., Aguirre, E., Orrell, M., & Spector, A, Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group. (2023). Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia (Review) [Art. No.: CD005562.]. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2023(1), 1–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005562.pub3

- Yates, L. A., Leung, P., Orgeta, V., Spector, A., & Orrell, M. (2015). The development of individual cognitive stimulation therapy (iCST) for dementia. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 10, 95–104.https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S73844

- Yates, L., Orrell, M., Leung, P., Spector, A., Woods, B., & Orgeta, V. (2019). Making a difference 3. Individual Cognitive Stimulation Therapy. A manual for carers (2nd ed.) Hawker Publications.

- Yates, L., Orrell, M., Leung, P., Spector, A., Woods, B., & Orgeta, V. (2021). Å gjøre en forskjell 3. Individuell kognitiv stimuleringsterapi. En manual for pårørende og omsorgspersoner (T. Holthe, Weum, R., Rønqvist, T.K., Trans.). Forlaget aldring og helse.