Abstract

Objective

Previous research has shown that daily activities are crucial for mental health among older people, and that such activities declined during the COVID-19 pandemic. While previous studies have confirmed a link between stringent restrictions and an increase in mental ill-health, the role of daily activities as a mediator in this relationship remains underexplored. We analyzed whether reductions in daily activities mediated the impact of these COVID-19 restrictions on mental ill-health during the pandemic’s initial phase.

Methods

We used data from Wave 8 SHARE Corona Survey covering 41,409 respondents from 25 European countries and Israel as well as data on COVID-19 restrictions from the Oxford Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT). Multilevel regression and multilevel-mediation analysis were used to examine the relationships between restrictions, daily activities and mental ill-health.

Results

Reductions in walking and shopping showed a notably stronger association with increases in mental ill-health compared to social activities. Furthermore, declines in walking could account for about a quarter of the relationship between restrictions and increased mental ill-health, but the mediating effects of the other activates were negligible.

Conclusions

The study highlights the essential role of maintaining daily activities, particularly walking, to mitigate the negative psychological effects of pandemic-related restrictions among older populations in Europe.

Introduction

The rapid outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 led to a sharp decline in out-of-home daily activities among people worldwide (c.f. Fors Connolly et al., Citation2021). Previous research on daily activities during the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed substantial variations across countries (Mendolia et al., Citation2021; Santamaria et al., Citation2020), with these differences partly attributable to the stringency of governmental restrictions and the overall spread of the pandemic (Fors Connolly et al., Citation2021 Mendolia et al., Citation2021; Santamaria et al., Citation2020). Notably, studies have also found that these two factors are associated with mental ill-health, as people in countries with stricter restrictions and higher infection rates report larger increases in mental ill-health (Atzendorf & Gruber, Citation2022; García-Prado et al., Citation2022; Knox et al., Citation2022). In this study, we explore the connections between restrictions, daily activities, and mental ill-health, examining whether daily activities serve as a mediator in the relationship between restrictions and mental ill-health among older people in Europe. Several studies have explored potential factors contributing to a decline in well-being and mental health during the pandemic across age groups. These factors include changes in working conditions (Zoch et al., Citation2022), income reductions (Yue & Cowling, Citation2021), shifts in social capital (Sarmiento Prieto et al., Citation2023), alterations in creative activities (Kyriazos et al., Citation2021), yielding mixed results. However, no research has yet probed the role of daily activities as a mediator between pandemic restrictions and mental health specifically among the older population.

While the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated mental health issues among older individuals due to challenges in accessing telemedicine and outpatient clinics, heightened anxiety about infection and inadequate care, and age-based discrimination fueled by media portrayals (Tsamakis et al., Citation2021), the impact of reduced daily activities also warrant considerations. Radwan et al. (Citation2020) and Sepúlveda-Loyola et al. (Citation2020) pointed to the possible negative long-term impact of stringent policy-mandated restrictions on older adults’ health, as the reduction in social contact and fewer physical activities may have long-term negative consequences for both their physical and mental health. Hoffman et al. (Citation2022) found that old age predicted a decline in physical activities during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US, which in turn was associated with a decline in physical functioning. However, possible effects of mental ill-health were absent from the analysis. Takiguchi et al., Citation2023 examined the link between decreased leisure activities and depressive symptoms in a Japanese sample. They found no association between reduced leisure activities and depression in the older segment of the sample (60–89). However, the findings are limited by a small sample size of only 122 individuals from this age group and the study’s confinement to Japan. Additionally, the researchers did not explore the potential distinctions between reductions in different leisure activities in relation to mental health during the pandemic.

Research from non-pandemic settings suggests that social and physical activities play a crucial role in emotional well-being (Bergstad et al., Citation2012) and mental health (Morgan et al., Citation2007; Paluska & Schwenk, Citation2000).Footnote1 Social activities, such as interacting with friends, family members, and participating in group events or organizations, have consistently been found to be positively associated with subjective well-being and mental health. Social support is a crucial element of this relationship, as it has been shown to promote psychological resilience, reduce stress, and buffer against the negative effects of life events (Cohen & Wills, Citation1985; Thoits, Citation2011). Furthermore, engaging in social activities provides individuals with opportunities to develop and maintain social networks, which can contribute to increased self-esteem, feelings of belonging, which in turn may increase well-being and mental health (Diener & Seligman, Citation2002; Leary & Baumeister, Citation1995).

The benefits of physical activity for subjective well-being and mental health are well-established. Regular physical activity has been shown to reduce the risk of depression and anxiety, improve mood, enhance cognitive function, and increase overall life satisfaction (Paluska & Schwenk, Citation2000; Penedo & Dahn, Citation2005; Schuch et al., Citation2018). Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the relationship between physical activity and subjective well-being and mental health. For instance, the release of endorphins and other neurotransmitters during exercise may improve mood and reduce feelings of stress and anxiety (Mead et al., Citation2009). Additionally, engaging in physical activity can provide opportunities for social interaction and support, which can further enhance subjective well-being and mental health (Eime et al., Citation2013).

Older adults may often face increased vulnerability to declines in daily activities as compared to younger individuals. For instance, while younger people might seamlessly transition to online substitutes for social activities, such as video chatting, this shift might be less straightforward for older adults. Additionally, the enhanced health benefits of physical activities for older individuals, as noted by Cunningham & O’ Sullivan (Citation2020), suggest that a reduction in physical activities during the pandemic could pose a more significant challenge for this age group than for younger people. However, interestingly, various studies have observed that older adults (at least in some countries) experienced a less noticeable increase in mental ill-health during the pandemic than their younger counterparts (Fields et al., Citation2022; Takiguchi et al., 2023). This could potentially be attributed to higher resilience among the older population (Fields et al., Citation2022). In addition, the unprecedented nature of the pandemic may have changed the impact of activity reduction on mental ill-health when compared to typical circumstances for older people. For example, reducing visits to relatives in non-pandemic circumstances might have adverse effects on the relationships with these relatives, which in turn could affect mental health negatively. However, during the pandemic, a reduction in visits to relatives might have been perceived as perfectly legitimate due to health concerns, thus mitigating potential negative effects on relationship quality and mental health. Furthermore, the experience of reducing participation in social gatherings, such as going to clubs, associations and religious ceremonies may have been more tolerable given that the majority of the elderly also had to curtail the same activities, fostering a sense of collective solidarity (‘we are all in the same boat’). This shared experience could have altered the relationship between activity reduction and mental health during the pandemic compared to normal circumstances and especially so for older people. In support, Greig et al. (Citation2022) observed a less pronounced correlation between loneliness and depressive symptoms among older individuals during the pandemic, as opposed to the year preceding it.

The present study

Since most prior research on the relationship between social and physical activities and well-being or mental health has been conducted in non-pandemic contexts, it remains an open question as to how these relationships may differ during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, to form expectations regarding this relationship, we will use previous studies on the association between various activities and well-being as a reasonable foundation. Drawing on these non-pandemic findings, we would anticipate a decline in mental health during the pandemic if it hindered people’s engagement in social and physical activities. Consequently, the first hypothesis we examine in this article is whether a reduction in social and physical activities during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with an increase in mental ill-health among older individuals.

To operationalize our hypothesis using available data, we examine whether a reduction in walking, a common physical activity among older people, is associated with an increase in mental ill-health. We further test our hypothesis by focusing on two important social activities (meeting family members who do not live in the same household and attending social gatherings) to determine whether a decline in social activities are also related to mental ill-health. Additionally, we investigate if a reduction in shopping is associated with an increase in mental ill-health. Although shopping might not be classified as a social or physical activity, it could be a common activity that still holds moderate importance for the mental health of older individuals. While not focusing on the older population per se, a comprehensive study on the relationships between daily activities and momentary emotional well-being (Killingsworth and Gilbert, Citation2010) suggests that shopping is more enjoyable than more passive leisure activities such as watching TV, listening to the radio, and reading.

Our second and primary hypothesis is that activity reduction serves as a mediator between restrictions and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Intriguingly, while numerous studies have explored the effects of restrictions on mental health (e.g. Atzendorf & Gruber et al., Citation2022), none have attempted to empirically establish daily activities as mediators in this relationship. Therefore, we anticipate that walking, shopping, and social activities would decrease as a result of stricter governmental restrictions, subsequently leading to increased mental ill-health among older individuals in Europe.

Data and methods

Study overview

The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) is a longitudinal, cross-sectional study of adults aged 50 and above living in 27 European countries and Israel (Börsch-Supan et al., Citation2013). To date, SHARE comprises nine survey waves, including two special COVID-19 waves. The data used in this study is drawn from the first SHARE Corona Survey (SCS1) (Börsch-Supan, Citation2022) conducted through computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI) with 54,567 respondents from June to August 2020 (Scherpenzeel et al., Citation2020). The SCS1 samples was selected in each country and included a) regular SHARE panel members that was already interviewed in wave 8 and b) regular SHARE panel members not been interviewed in wave 8 due to interruption of the field work caused by the COVID-19 outbreak (Bergmann & Bethmann, Citation2021; Scherpenzeel et al., Citation2020). The individual retention rate of the CATI sample in the participating countries range from 60% to 96%, and approximately half of all countries attained a retention rate over 80%Footnote2 (Sand, Citation2021). The survey targeted the COVID-19 living situation of older persons during the pandemic and covered questions related to health and health behaviour; information on COVID-19 infections and quality of health care; changes in work and economic situation and social relationships. The full questionnaire is available at: Corona Questionnaire 1 (share-eric.eu).

Additionally, aggregated data on governmental policy responses were obtained from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT), a composite measure based on data on country-specific responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as school and workplace closures and travel restrictions. (Hale et al., Citation2021). We obtained data on confirmed COVID-19 cases and death for all countries from the COVID-19 Data Repository by the Centre for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University, maintained by Our World in Data (www.ourworldindata.org/covid-cases). The data provided daily information on confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths for each country.

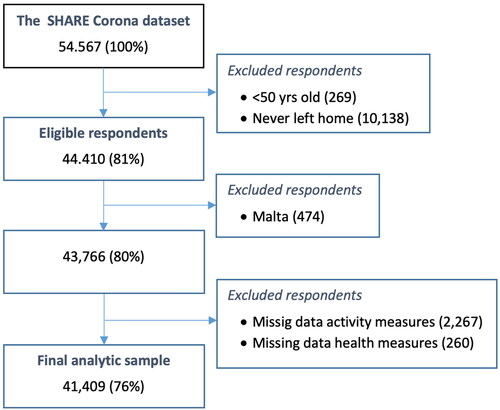

Our study sample consisted of 44,410 eligible respondents aged 50 years or older who had left their homes at least once since the COVID-19 pandemic began (). Participants from Malta (n = 474) were excluded from the dataset due to the lack of official country-level data on governmental restrictions during the pandemic. Following the removal of respondents due to item non-response on activity measures (n = 2,267) and mental health measures (n = 260), the final analytical sample size comprised 41,409 respondents from 26 countries: Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, France, Denmark, Greece, Switzerland, Belgium, Czech Republic, Poland, Luxembourg, Hungary, Portugal, Slovenia, Estonia, Croatia, Lithuania, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Latvia, Romania, Slovakia, and Israel as the only non-European country.

Measures

Measurements of mental ill-health

In Wave 8, the SHARE Corona Survey assessed changes of mental health through the following questions: ‘In the last month, have you been sad or depressed?’ (yes/no); ‘In the last month, have you felt nervous, anxious, or on edge?’ (yes/no); ‘Have you had trouble sleeping recently?’ (yes/no); and ‘How much of the time do you feel lonely?’ (Often, some of the time, or hardly ever/never) Respondents who answered ‘no’ or hardly never/never were coded as zero. Those who answered ‘yes’ to questions about sadness/depression, anxiety and sleep problem were followed up with the question: ‘Has that been more so, less so or about the same as before the outbreak of Corona?’ To capture changes in mental ill-health, we dichotomized the variables into ‘more so’ (1) and ‘less so/about the same’ (0). We created an additive index by combining all variables, including self-reported changes in sadness/depression, anxiety, sleep problems, and feelings of loneliness. The reliability of this index, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, varied from 0.48 in Denmark to 0.77 in Slovakia, with an average value of 0.66 across all countries (alpha values for all countries are displayed in Appendix Table A1). Although this value is slightly below the conventional cut-off of 0.7, it was deemed acceptable considering that the index was based on only four binary indicators, as opposed to continuous variables.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, data: Wave 8 SHARE Corona Survey.

Measurements of activity reduction

Reduction of daily activities was measured through four variables: ‘Going shopping’, ‘Going out for a walk’, ‘Meeting with more than five people from outside your household’ and ‘Visiting other family members’. Respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they adjusted their daily activities since the outbreak of the Corona pandemic, compared to before the outbreak. The activities were dichotomized into two values: respondents who reported ‘Not anymore’ or ‘Less often’ were coded as 1, indicating a reduction in activity, while those who reported ‘About the same’ or ‘More often’ were coded as 0.

Governmental restrictions

The Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) is a stringency index on the country level that measures the strictness of COVID-19 restrictions on a scale from 0 to 100, with 100 representing the highest level of stringency (Hale et al., 2021). We calculated mean values for all countries between 1 March and 31 July 2020, which corresponds to the period when COVID-19 broke out and the timeframe of the first SHARE Corona Survey fieldwork.

Covariates

At an individual level age is grouped into two categories: 50–69 years and 70 years and older. Employment status when the pandemic broke out is measured as 1 ‘Employed/self-employed’ 0 ‘Not employed’. Household size was dichotomized into 1 ‘Single household’ 0 ‘Living with two or more persons in a household’. The respondent’s health status was measured with two variables: health before pandemic outbreak (1 ‘Good health’, 0 ‘Fair/poor health’) and health change after pandemic outbreak (1 ‘Improved/about the same’ 0 ‘Worsened’).

At the country level, given that both confirmed cases and deaths can serve as indicators of the overall spread of COVID-19 (Mendolia et al., Citation2021), we calculated an infection rate measure for all countries by combining the reported cases and deaths (for more information see Fors Connolly et al., Citation2021).

Analytical approach

In order to examine the associations between (i) levels of stringency and activity reductions, and (ii) activity reductions and increased mental ill-health, we conducted multilevel logistic regression (using a probit link) and multilevel regression, respectively. In a final step, multilevel-mediation analyses were carried out to examine the mediating effects of activity reductions in the association between increased mental ill-health and stringency levels.

For each association in (i) and (ii), both a simple unadjusted and a fully covariate adjusted model were fitted. Moreover, in all models, countries were included as random intercepts (level 2-units), to take into account country-specific differences. The simple models did not include any explanatory variables and only included stringency and/or activity reductions. Specifically, in step (i), a multilevel logistic regression model was fitted for each activity separately to assess the association between stringency and the activity. In (ii), to assess the association between the different activities and mental ill-health, one multilevel regression model was fitted (including all activities). The fully covariate adjusted models were fitted in a similar way, although they also included the explanatory variables: sex, age, employment status, household composition, subjective pre-pandemic health, as fixed additive predictors at the individual-level (level 1-units), and infection rate was included as a fixed predictor at country level (level 2-unit).

Multilevel-mediation analyses were carried out to examine the mediating effects of activity reductions (separate models for each activity) in the association between increased mental ill-health and stringency levels. For an activity to be identified as a mediator, it must satisfy two conditions; i) the variable is significantly correlated with stringency levels, and ii) the variable is significantly correlated with the mental ill health when adjusting for the confounding factors in the multilevel model. Similarly, both a simple unadjusted and a fully covariate adjusted model were fitted. The latter, including the same set of covariates (as well as the other activities when regressing mental ill-health on the activities) and countries as random intercepts. A nonparametric bootstrap method was used to generate a sampling distribution and test the statistical significance of the mediation effects (i.e. the total effect, the direct effect, and the mediating effect). Confidence intervals were estimated based on results from N = 1,000 samples. The mediation results are presented as (i) the indirect or mediating effect of activity reduction (Walking, Shopping, People or Family) in the association between stringency levels and mental-ill health, (ii) the direct effect of stringency levels on mental ill-health while controlling for activity, and (iii) the total effect of stringency levels on mental ill-health, corresponding to the sum of the direct and the mediating effect.

All analyses were carried out using R 4.3.0 and the R-packages; lme4 (Bates et al., Citation2015), lmerTest (Kuznetsova et al., Citation2017) and mediation (Tingley et al., Citation2014).

Results

Descriptives

summarizes descriptive statistics for the analytical sample. The sample comprises N = 41,409 subjects, of which 56 % women and nearly half of the respondents are 70 years or older. About one-quarter of the respondents were employed when COVID-19 broke out and the majority lived in a multi-person household. Regarding health, 28 % reported fair or poor health before the pandemic. A majority (over 60 %) of the respondents reduced their daily activities, except for going walking, where only 46% reduced their walking habits, during the pandemic.

The association between stringency and activity reduction – multilevel modeling

Separate multi-level models, both simple and fully covariate-adjusted, were fitted regressing each activity on stringency levels. Results from the simple models (see Appendix Table A2) show that levels of stringency are positively associated with activity reduction across all four activities. However, the only significant association is seen for walking (β = 0.39, p < .001), in contrast to meeting more than 5 people (β = 0.11, p = .122), meeting family members (β = 0.08, p = .144) and going shopping (β = 0.02, p = .733). For the fully adjusted models (see ), the association between stringency and walking are similar to the simple model (β = 0.41, p < .001). The association of stringency on meeting more than 5 people and meeting other family members both display weak effects (β = 0.04, p = .421 and β < 0.00 p = .986, respectively). A small negative association was found for shopping on stringency (β=-0.11, p = .03).

Table 2. Regressing stringency on activities while adjusting for covariates and other activities.

The association between activity reduction and mental ill-health – multilevel modeling

The first hypothesis posited a relationship between a reduction in social and physical activities and increased mental ill-health in this cohort of older people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, we begin by analyzing simple (unadjusted) separate models of associations between the four activities and mental ill-health (see Appendix, Table A3). Results show that a reduction in each of the four activities are related to increased mental ill-health (all p < .001). However, since each activity is substantially correlated with all other activities, we next run models controlling for all other activities as well as a series of other relevant control variables, i.e. a fully adjusted model (see ). The results from this model show that all four activities continue to display statistically significant relationships with mental ill-health; however, their effects are more attenuated compared to those in the simple models. The strongest association is observed for shopping (β = 0.04, p < .001), followed by walking (β = 0.03, p < .001), meeting family members (β = 0.02, p < .001) and meeting more than five people (β = 0.01, p = .014). Moreover, among the control variables, pre-pandemic health displayed the strongest association, followed by gender and living in a single household (all p < .001). Age and being employed also display statistically significant associations with mental ill-health (p < .008). However, these associations are notably weaker (β = −0.01 and β = 0.01, respectively).

Table 3. Regressing activities on mental ill-health while adjusting for covariates and other activities.

An additional hypothesis, based on previous research, was that physical activity (walking) and the two social activities (meeting more than 5 people and meeting family members) would predict mental ill-health better than shopping. However, this was not the case. In fact, the two social activities displayed weaker associations compared to walking and shopping. Although walking was more strongly associated with mental ill-health than the two social activities, the association was still somewhat weaker than the corresponding association between shopping and mental ill-health.

Stringency, activity reduction and mental ill-health – mediation results

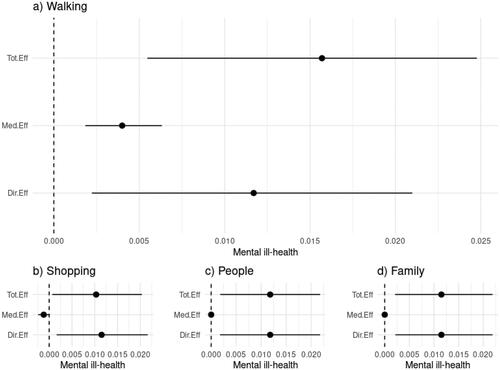

Our second hypothesis was that activity reductions would act as mediators between stringency and mental ill-health during the COVID-19 pandemic. To investigate this, we run a series of multilevel-mediation models with restrictions as the independent variable, mental ill-health as the dependent variable (outcome) and each of the four activities as separate mediators. Note, of the included activity reductions only walking was formally identified as a mediator.

In the simple (unadjusted) models, with each activity as a separate mediator, we find that only walking of the four activities (partially) mediates the effect of restrictions on mental ill-health. As such, walking explains about 34% of the association between stringency and mental ill-health. The results show a significant total effect of stringency and mental ill-health (tot.eff = 0.016, CI: 0.003–0.028) and a significant mediating effect of walking (med.eff = 0.005, CI: 0.002–0.008). None of the other activities display any meaningful mediating effects (all CIs cover zero) and they explain less than 15% of the association between stringency and mental ill- health, i.e. shopping: 15%, People 1%, and Family <1% (see Appendix Table A4 a-d).

To draw more precise conclusions about the potential mediation role of walking, we now examine a fully adjusted mediation model, which accounts for each activity as well as the explanatory variables used in the previous analysis (see and Appendix Table A5 a-d). The results reveal that stringency continues to show a statistically significant association with mental ill-health (tot.eff = 0.016, CI: 0.006 − 0.025), and a significant indirect effect through reductions in walking (med.eff = 0.004, CI: 0.002 − 0.006). However, the effect moderately attenuates for the fully adjusted model compared to the unadjusted model. Suggesting that the control variables have a modest impact on the relationship between stringency, walking, and mental ill-health.

Figure 2. Mediation results from the fully adjusted model. The results are presented as (i) the indirect or mediating (med.Eff) of activity reduction (walking, shopping, people or family) in the association between stringency levels and mental-ill health, (ii) the direct effect (dir.Eff) of stringency levels on mental ill-health while controlling for activity, and (iii) the total effect (tot.Eff) of stringency levels on mental ill-health, corresponding to the sum of the direct and the mediating effect.

In sum, we found that reductions in daily activities, particularly walking and shopping, were associated with an increase in mental ill-health among older individuals during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Surprisingly, the two social activities examined had relatively weak effects. Moreover, the results of the multilevel-mediation analysis provided partial support for our hypotheses. Walking emerged as a significant mediator in the relationship between governmental restrictions and mental ill-health, while other activities did not demonstrate any significant mediating effects.

General discussion

Prior research has demonstrated that stricter governmental restrictions are associated with a greater reduction in daily activities and increased mental ill-health among older individuals in Europe. However, to our knowledge, no studies have explored the reasons behind this relationship by examining daily activities as potential mediators. In this study, we investigated whether the effects of restrictions on mental ill-health were mediated by a decrease in daily activities during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe. Our findings revealed that self-reported reductions in walking, shopping, and social activities (such as meeting family members and attending social gatherings) were all independently associated with a self-reported increase in mental ill-health among older people in Europe. Furthermore, reductions in walking and shopping exhibited a notably stronger association with increases in mental ill-health compared to reductions in the two social activities.

In examining our primary results, our analysis revealed that a decrease in walking accounted for approximately one-quarter of the relationship between governmental restrictions and self-reported increases in mental ill-health. In contrast, reductions in shopping and social activities exhibited minimal mediating effects. These findings imply that one explanation for the association between restrictions and mental ill-health among older individuals in Europe, as identified in prior research, can be attributed to reductions in walking.

The lack of a mediating effect of shopping and social activities on mental well-being, together with the weak association between reduced social activities and mental health, is partly consistent with findings by Takiguchi et al. (2023). Their research revealed no significant relationship between a decline in leisure activities and depressive symptoms among the elderly in Japan during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

It may still seem surprising that a reduction in social activities only showed a weak correlation with increasing mental health issues among older people in Europe, especially considering that social activities have been identified as crucial determinants of well-being in numerous past studies. Furthermore, previous studies have suggested that reducing social activities can be particularly detrimental to older people because social interactions are highly valued within this group, as reported by Zhaoyang et al., Citation2019. However, we propose several possible explanations for this result. First, people may have regarded reductions of social activities as a temporary situation during the pandemic, for this reason, it may have had a less effect on their well-being compared to in non-pandemic situations. Second, social cohesion may have been strong during the initial phase of the pandemic which may have given people a sense of connection with other people regardless of whether they actually interacted with other people in real life. Third, our measures of social activities (meeting family members and meeting more than five people) were not exhaustive, for instance, we were not able measure whether the participants reduced meeting their friends or neighbours. Fourth, taking part in social gatherings may be a relatively infrequent activity among older people and for this reason be less important for their well-being. Fifth, and finally, it may be that elderly people in Europe have effectively substituted face-to-face interactions with online communication platforms, such as Zoom. However, Litwin & Levinsky’s research (Citation2022) suggests that, throughout the first phase of the pandemic, there was no notable link between the frequency of electronic communication usage and depression levels among the elderly in Europe. In comparison, face-to-face contact appeared to be associated with lower instances of depression during the same period.

Why, then, did shopping and walking exhibit stronger associations with mental ill-health compared to meeting family members and attending social gatherings? One possible explanation is that both shopping and walking are activities performed more frequently, making reductions in these activities more noticeable in people’s daily lives. Shopping may not be as enjoyable as socializing with loved ones, but it can still be a frequent and somewhat satisfying activity as indicated by previous studies on emotional well-being (c.f. Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010). It can, therefore, play a significant role in promoting mental health among older people. In addition, both shopping and walking may often include various forms of social interactions. For instance, many people may have gone for walks with friends and family in countries with high restrictions during the pandemic. Regarding shopping, it is also possible that the reduction in this activity may have had negative effects on mental health for reasons beyond the enjoyment of the activity itself. For example, individuals might have struggled to obtain goods such as their preferred food and other essential items, which could contribute to negative feelings.

A major strength of the study is the large sample size, inclusion of 26 countries and relatively representative samples in each country. However, we acknowledge several limitations. We were only able to study four different activities due to data limitation, hence other kinds of activities, like meeting friends or neighbors, may also have played an important role on mental health. Further, the relations we found between stringency, activity reduction and mental ill-health could potentially differ for older people in countries other than those included. Moreover, we used somewhat crude self-reported measures of both activity reduction and mental ill-health which may bias observed relationships toward zero. Last, we used a cross-sectional correlational research design. Hence, observed associations between stringency, activity reduction and mental health could potentially be explained by confounding factors (not accounted for in our analysis) or by reversed causality between activity reduction and mental health.

Based on the results of this study, we can derive several potential policy implications for addressing mental health of older individuals during periods of governmental restrictions, such as those imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings indicate that a reduction in walking activities mediates a significant portion of the relationship between restrictions and increased mental ill-health among older people in Europe. As a result, policymakers should consider implementing measures that encourage and facilitate walking and other forms of physical activity, even during times of crisis or lockdown. This could include the development of safe outdoor spaces, such as parks and walking trails, as well as public health campaigns promoting the benefits of regular physical activity for mental well-being.

While the reduction of social activities was found to have a weaker association with mental ill-health among older people, it is still essential to consider alternative ways to maintain social connections during periods of restrictions. Policymakers could promote the use of technology for virtual communication, support the organization of safe and socially-distanced community events, or invest in initiatives that target social isolation and loneliness among older adults. However, it is important to take into account that use of digital technologies may actually increase social isolation for some groups of older people (Beaunoyer et al., Citation2020; Figueroa and Aguilera, Citation2020).

In light of the stronger association between shopping activities and mental ill-health compared to social activities, it is crucial to ensure that older adults have access to essential services such as grocery stores, pharmacies, and healthcare facilities during times of restrictions. Policymakers should consider implementing measures that enable safe access to these services, such as dedicated shopping hours for older people or delivery services for those unable to leave their homes.

Ultimately, the results of this study highlight the importance of maintaining daily activities, especially walking, for older individuals during periods of restrictions. By implementing targeted policies and interventions, we can help mitigate the negative impacts of such restrictions on mental health and well-being of older adults in Europe and beyond.

Ethics approval

The ethical review board in Sweden has approved SHARE in general (Dnr 2012/373-31) and the specific COVID-19 Project (Dnr 2021-03581), which this study is part of.

Informed consent

Data used in our article involved human subjects who consented to participate in SHARE, see www.share-project.org

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (89.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

This paper uses data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE): Wave 8, release version 8.0.0, DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w8.800 and Wave 8 COVID-19 Survey 1, release version 8.0.0 DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w8ca.800, https://share-eric.eu/data/.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In our literature review, we do not draw a distinct line between subjective well-being and mental health, as these two constructs exhibit considerable overlap. This is particularly relevant in our study, as our operationalization of mental ill-health focuses on symptoms of depression and anxiety, which are frequently incorporated into measures of the affective component of subjective well-being.

2 For more information on sampling, monitoring and managing of fieldwork during the SHARE Corona Survey, see Bergmann& Börsch-Supan (Citation2021) and Scherpenzeel et al. (Citation2020).

References

- Atzendorf, J., & Gruber, S. (2022). Depression and loneliness of older adults in Europe and Israel after the first wave of covid-19. European Journal of Ageing, 19(4), 849–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-021-00640-8

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using LME4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

- Beaunoyer, E., Dupéré, S., & Guitton, M. J. (2020). COVID-19 and digital inequalities: Reciprocal impacts and mitigation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior, 111, 106424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106424

- Bergmann, M., & Bethmann, A. (2021). Sampling for the first SHARE Corona Survey after the suspension of fieldwork in wave 8. In Bergmann, M. & Börsch-Supan, A. (Eds.). (2021). SHARE Wave 8 Methodology: Collecting cross-national survey data in times of COVID-19. MEA, Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy.

- Bergmann, M., & Börsch-Supan, A. (2021). SHARE wave 8 methodology: Collecting cross-national survey data in times of COVID-19. MEA, Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy.

- Bergstad, C. J., Gamble, A., Hagman, O., Polk, M., Gärling, T., Ettema, D., Friman, M., & Olsson, L. E. (2012). Influences of affect associated with routine out-of-home activities on subjective well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 7(1), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-011-9143-9

- Börsch-Supan, A. (2022). Survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (SHARE) wave 8. COVID-19 Survey 1. Release version: 8.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w8ca.800

- Börsch-Supan, A., Brandt, M., Hunkler, C., Kneip, T., Korbmacher, J., Malter, F., Schaan, B., Stuck, S., & Zuber, S. (2013). Data resource profile: The survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (SHARE). International Journal of Epidemiology, 42(4), 992–1001. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt088

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

- Cunningham, C., & O’ Sullivan, R. (2020). Why physical activity matters for older adults in a time of pandemic. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity, 17(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11556-020-00249-3

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00415

- Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J., & Payne, W. R. (2013). A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-98

- Fields, E. C., Kensinger, E. A., Garcia, S. M., Ford, J. H., & Cunningham, T. J. (2022). With age comes well-being: Older age associated with lower stress, negative affect, and depression throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging & Mental Health, 26(10), 2071–2079. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.2010183

- Figueroa, C. A., & Aguilera, A. (2020). The need for a mental health technology revolution in the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 523–523. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00523

- Fors Connolly,. F., Olofsson, J., Malmberg, G., & Stattin, M. (2021). Adjustment of daily activities to restrictions and reported spread of the COVID-19 pandemic across Europe. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.17617/2.3292885

- García-Prado, A., González, P., & Rebollo-Sanz, Y. F. (2022). Lockdown strictness and mental health effects among older populations in Europe. Economics and Human Biology, 45, 101116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2022.101116

- Greig, F., Perera, G., Tsamakis, K., Stewart, R., Velayudhan, L., & Mueller, C. (2022). Loneliness in older adult mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic and before: Associations with disability, functioning and pharmacotherapy. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 37(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5630

- Hale, T., Angrist, N., Goldszmidt, R., Kira, B., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., Webster, S., Cameron-Blake, E., Hallas, L., Majumdar, S., & Tatlow, H. (2021). A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 government response tracker). Nature Human Behaviour, 5(4), 529–538. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8

- Hoffman, G. J., Malani, P. N., Solway, E., Kirch, M., Singer, D. C., & Kullgren, J. T. (2022). Changes in activity levels, physical functioning, and fall risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 70(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17477

- Killingsworth, M. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science (New York, N.Y.), 330(6006), 932. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1192439

- Knox, L., Karantzas, G. C., Romano, D., Feeney, J. A., & Simpson, J. A. (2022). One year on: What we have learned about the psychological effects of COVID-19 social restrictions: A meta-analysis. Current Opinion in Psychology, 46, 101315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101315

- Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2017). ImerTest Package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82(13), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13

- Kyriazos, T., Galanakis, M., Karakasidou, E., & Stalikas, A. (2021). Early COVID-19 quarantine: A machine learning approach to model what differentiated the top 25% well-being scorers. Personality and Individual Differences, 181, 110980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110980

- Leary, M. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Litwin, H., & Levinsky, M. (2022). Social networks and mental health change in older adults after the Covid-19 outbreak. Aging & Mental Health, 26(5), 925–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1902468

- Mead, G. E., Morley, W., Campbell, P., Greig, C. A., McMurdo, M., & Lawlor, D. A. (2009). Exercise for depression. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3(3), CD004366. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub4

- Mendolia, S., Stavrunova, O., & Yerokhin, O. (2021). Determinants of the community mobility during the COVID-19 epidemic: The role of government regulations and information. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 184, 199–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2021.01.023

- Morgan, C., Burns, T., Fitzpatrick, R., Pinfold, V., & Priebe, S. (2007). Social exclusion and mental health: Conceptual and methodological review. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 191(6), 477–483. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.034942

- Paluska, S. A., & Schwenk, T. L. (2000). Physical activity and mental health: Current concepts. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 29(3), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200029030-00003

- Penedo, F. J., & Dahn, J. R. (2005). Exercise and well-being: A review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 18(2), 189–193. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001504-200503000-00013

- Radwan, E., Radwan, A., & Radwan, W. (2020). Challenges facing older adults during the COVID-19 outbreak. European Journal of Environment and Public Health, 5(1), em0059. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejeph/8457

- Sand, G. (2021). Monitoring and managing SHARE fieldwork in the first Corona Survey. In Bergmann, M. & Börsch-Supan, A. (Eds.) (2021). SHARE Wave 8 Methodology: Collecting cross-national survey data in times of COVID-19. MEA, Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy.

- Santamaria, C., Sermi, F., Spyratos, S., Iacus, S. M., Annunziato, A., Tarchi, D., & Vespe, M. (2020). Measuring the impact of COVID-19 confinement measures on human mobility using mobile positioning data. A European regional analysis. Safety Science, 132, 104925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104925

- Sarmiento Prieto, J. P., Castro‑Correa, C., Arrieta, A., Jerath, M., & Arensburg, S. (2023). Relevance of social capital in preserving subjective well-being in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, 14(2) , 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/rhc3.12260

- Scherpenzeel, A., Axt, K., Bergmann, M., Douhou, S., Oepen, A., Sand, G., Schuller, K., Stuck, S., Wagner, M., & Börsch-Supan, A. (2020). Collecting survey data among the 50+ population during the COVID-19 pandemic: The survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (SHARE). Survey Research Methods, 14(2), 217–221.

- Schuch, F. B., Vancampfort, D., Richards, J., Rosenbaum, S., Ward, P. B., & Stubbs, B. (2018). Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 96, 56–66.

- Sepúlveda-Loyola, W., Rodríguez-Sánchez, I., Pårez-Rodriuez, P., Ganz, F., Torralba, R., Oliveira, D. V., & Rodríguez-Mañas, L. (2020). Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on health in older people: Mental and physical effects and recommendations. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Ageing, 5(9), e256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1500-7

- Takiguchi, Y., Matsui, Mie., Kikutani, M., & Ebina, K. (2023). The relationship between leisure activities and mental health: The impact of resilience and COVID-19. Applied Psychology. Health and Well-Being, 15(1), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12394

- Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510395592

- Tingley, D., Yamamoto, T., Hirose, K., Keele, L., & Imai, K. (2014). Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis.

- Tsamakis, K., Tsiptsios, D., Ouranidis, A., Mueller, C., Schizas, D., Terniotis, C., Nikolakakis, N., Tyros, G., Kympouropoulos, S., Lazaris, A., Spandidos, D. A., Smyrnis, N., & Rizos, E. (2021). COVID-19 and its consequences on mental health. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 21(3), 244. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2021.9675

- Yue, W., & Cowling, M. (2021). The Covid-19 lockdown in the United Kingdom and subjective well-being: Have the self-employed suffered more due to hours and income reductions? International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 39(2), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242620986763

- Zhaoyang, R., Sliwinski, M. J., Martire, L. M., & Smyth, J. M. (2019). Social interactions and physical symptoms in daily life: quality matters for older adults, quantity matters for younger adults. Psychology & Health, 34(7), 867–885. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2019.1579908

- Zoch, G., Bächmann, A., & Vicari, B. (2022). Reduced well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic – The role of working conditions. Gender, Work & Organization, 29(6), 1969–1990. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12777