Abstract

Objectives

The goal of the present meta-analysis was to compare effects of reminiscence interventions on depression and anxiety across different target groups.

Methods

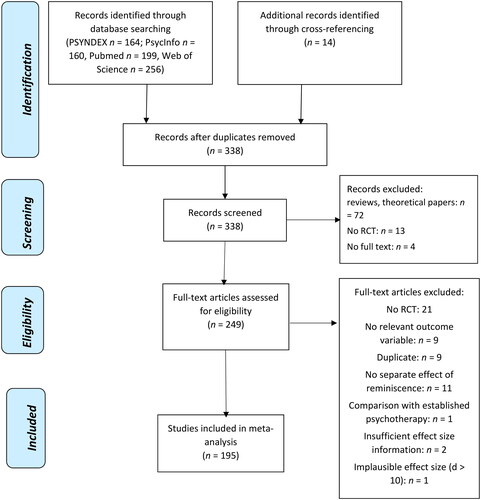

Systematic search in electronic data bases and cross-referencing identified 195 randomized controlled trials that were included in random-effects meta-analysis.

Results

Reminiscence interventions resulted, on average, in moderate improvement of depressive symptoms and small-to-moderate improvements of anxiety symptoms. Life review therapy for individuals with elevated psychological symptoms tended to be more effective (with moderate to strong improvements) than life review with nonclinical samples and simple reminiscence. Effects were similar for individuals with cognitive impairment, physical illness and general community-based samples. Intervention effects varied, in part, by intervention length, kind of control condition, publication status, and region where the study was conducted.

Conclusions

We conclude that reminiscence interventions should be offered for all adults interested in reflecting on their past, although adaptations of intervention contents can be made according to the needs of potential participants.

Different types of reminiscence are increasingly used for reducing psychological symptoms and promoting other desirable outcomes (e.g. self-esteem, ego-integrity) in older adults and younger age groups. The present meta-analysis focuses on two groups of psychological symptoms—depression that has been most often addressed in reminiscence interventions (Pinquart & Forstmeier, Citation2012)—and anxiety that often co-occurs with depression (Elias et al., Citation2015).

Three basic types of reminiscence are often distinguished in the literature: simple reminiscence (SR), life review (LR) and life review therapy (LRT). SR refers to the recall of memories aimed at increasing psychological well-being. It is commonly offered in group format and is appropriate for all individuals who are open to reflecting on their past (Westerhof et al., Citation2010; Yan et al., Citation2023). LR consists of a structured approach aimed at recollecting, evaluating and integrating positive and negative memories. It is suited for individuals who are struggling to find meaning in their lives and may need help to integrate disparate parts of the self and reduce self-criticism (Westerhof et al., Citation2010). While LR may be offered to individuals with some psychological symptoms, LRT is a more formal and in-depth intervention used to treat adults with serious mental health problems (Westerhof et al., Citation2010). Although SR, LR and LRT have originally mainly been offered to older adults (Al-Ghafri et al., Citation2021; Ji et al., Citation2023; Tam et al., Citation2021), there is a growing number of applications to other target groups, such as adults of different ages with serious physical illness (for overview, Chen et al., Citation2017) and even adolescents (Esmaeili & Usefynezhad, Citation2016).

At least four processes may contribute to effects of reminiscence interventions on depressive symptoms (e.g. Hallford et al., Citation2019; Molinari, Citation2019), namely (1) passing one’s time in an enjoyable fashion may improve mood, (2) perceiving affirmation from others (group members and/or the interventionist) may promote positive self-evaluations and positive feelings, (3) reflecting on problems one solved in the past may strengthen feelings of control and self-efficacy, and (4) meaning (re)construction that helps with finding significance and order, even in memories of negative experiences. While the first two processes would be mainly relevant in the case of SR, all processes could work in LR and LRT, although meaning (re)construction is the core element of LR/LRT (Korte et al., Citation2012). Strengthening self-efficacy beliefs and feelings of control as well as promoting hope through reflecting on problems solved in the past may be, in particular, relevant for reducing anxiety symptoms (Elias et al., Citation2015; Hallford et al., Citation2019).

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are best suited for analyzing effects of reminiscence. We shortly summarize results of previous meta-analyses of RCTs on reminiscence interventions aimed at reducing depression and anxiety. For later comparisons with the present results, we mainly focus on meta-analyses that report effects in standard deviation units (i.e. d or g-scores). Three meta-analyses included studies with older adults without cognitive impairment. Tam et al. (Citation2021) found small-to-moderate improvements of depressive symptoms in participants of reminiscence-based interventions (d = 0.38, n = 8 studies). Based on 15 RCTs, Al-Ghafri et al. (Citation2021) found, on average, moderate improvements of depressive symptoms in response to LR at posttest (d = 0.54) and small improvements at follow-up (d = 0.36). Three meta-analyses on LRT found large improvements of depression at posttest (d = 0.81, Cuijpers et al., Citation2021; d = 1.08 when compared with non-active control condition and d = 0.85 when compared with an active control condition, Ji et al., Citation2023; d = 1.01, Westerhof & Slatman, Citation2019). Results of meta-analyses on the effects of reminiscence on older adults with dementia were inconsistent. While Thomas and Sezgin (Citation2021) reported that reminiscence did not significantly affect depressive symptoms of older adults with dementia (d = 0.28, n = 5 studies), Huang et al. (Citation2015) found small-to-moderate improvements of depressive symptoms (g = 0.49, n = 12), and Kim and Lee (Citation2019) observed even moderate improvements (g = 0.62, n = 22). A meta-analysis on LR with cancer patients found a significant improvement of anxiety symptoms (Sun et al., Citation2023, n = 7). Effects on change in anxiety symptoms in other target groups have not yet been summarized with meta-analysis.

Identifying characteristics of the participants and of the intervention that predict larger change in psychological symptoms is relevant for planning interventions and selecting individuals who are likely to benefit from them. While meta-analyses could, in principle, search for such moderating variables, most of the previously cited meta-analyses did not do this because of the limited number of included studies (e.g. Al-Ghafri et al., Citation2021, Tam et al., Citation2021; Westerhof & Slatman, Citation2019). Nonetheless, the meta-analysis on dementia patients by Kim and Lee (Citation2019) found weaker effects in studies with older patients and in longer interventions while dementia severity and intervention format (group vs. individual) showed no moderating effect. Huang et al. (Citation2015) observed stronger declines of depressive symptoms in institutionalized as compared to non-institutionalized dementia patients. As these moderating effects were only identified in studies on dementia, it remains open whether they can be generalized to other target groups.

In sum, previous meta-analyses found, on average, moderate to large improvements of depressive symptoms in cognitively intact older adults while improvements were small to moderate in older adults with cognitive impairment. However, results varied considerably between available meta-analyses, which may be based on variations in their focus (e.g. kind of reminiscence, target group) and on the fact that these meta-analyses included only an average of 12 studies, thus limiting the robustness of their estimations. In addition, meta-analyses on the effects of reminiscence on anxiety symptoms and on moderating effects were limited to a narrow target group (cancer and dementia patients, respectively). Thus, the goal of the present meta-analysis was to compare effects of different kinds of reminiscence on depression and anxiety across different populations and to search for moderating effects of sample and study characteristics, based on a large number of studies.

Research questions

The first research question asks for the average change of depressive and anxiety symptoms in participants of reminiscence interventions compared to a control group that did not receive this kind of intervention. Several processes could lead to change in response to LR/LRT compared to SR (Hallford et al., Citation2019; Molinari, Citation2019) and participants of LRT can be expected to have higher psychological symptoms at pretest than participants of SR and LR. Thus, the second research question asks whether improvements of depressive and anxiety symptoms will be strongest after LRT and weakest after SR. The third research question asks whether intervention effects differ between participants with elevated psychological symptoms at pretest, individuals with dementia or other forms of cognitive impairment, individuals with physical illness, and individuals from the general population.

The final research question asks for additional moderating effects of sample and study characteristics. Based on meta-analyses by Kim and Lee (Citation2019) as well as Huang et al. (Citation2015), we searched for moderating effects of age, intervention length, institutionalization, and individual versus group setting. In addition, moderating effects of gender (for exploratory reasons), kind of control conditions, and publication status are tested. There are, in part, contradictory results regarding whether effects of reminiscence are similar or different across the globe (Hofer et al., Citation2020). Thus, it is also tested whether the results vary between the regions of the globe.

Methods

Study selection

A systematic search in the electronic data bases PsycInfo, PubMed, PSYNDEX, and Web of Science was used for identifying studies, applying the combination of the search terms (reminiscence OR life review) AND (depress* OR anx*) AND random*. In addition, the reference sections of the identified papers were checked for additional studies. Studies were included if they:

provided results of a RCT on the effects of SR, LR, or LRT,

had a control condition that did not receive SR, LR or LRT (e.g. waiting list, attention placebo control condition)

assessed depressive symptoms and/or anxiety symptoms as an outcome variable

provided sufficient information for computing standardized mean differences in the outcome variables at posttest and/or follow-up

have been published before June, 2023.

Studies were excluded if reminiscence was only used as an aspect of multicomponent interventions so that specific effects of reminiscence could not be identified (n = 7). We also did not include studies that compared effects of LRT with an established alternative form of psychotherapy (n = 1) as effects of these studies have already been summarized in two recent reviews and as effects were found to strongly depend on the kind of comparator (Cuijpers et al., Citation2021; Ji et al., Citation2023). In addition, studies were excluded if they duplicated the results of included papers (n = 9) or reported implausible results (n = 1).

There was no restriction regarding the language of the publication, and native speakers or an electronic translation software were used if studies were published in languages other than English or German. Unpublished studies that were identified with the search in electronic data bases (e.g. dissertations) were included in order to diminish potential influences of a file-drawer problem on the results (Rosenthal, Citation1979). If the original manuscript was not available or information for computing effect sizes was lacking, the corresponding author was contacted in the case of having access to contact information. Study quality was evaluated based on Higgins et al. (Citation2022) and the ROB 2 tool (Sterne et al., Citation2019).

In total, 338 studies were identified. After screening and assessing for eligibility, 195 studies were included in the present meta-analysis. The PRISMA flow chart (Page et al., Citation2021) is depicted in and information on the included studies is given in the electronic supplement S1 and S2.

The following variables were coded: author(s), number of participants in the reminiscence condition and in the control condition, dropout rate, country of data collection, publication status (1 = published, 2 = unpublished), mean age, percentage of female participants, selection of participants based on illness/symptoms at pretest (1 = none, 2 = mental health problems, 3 = dementia/cognitive impairment, 4 = physical illness), residence (1 = private home, 2 = institutionalization, 3 = mixed/not reported), type of reminiscence (1 = SR, 2 = LR, 3 = LRT), setting (1 = individual, 2 = group), number of sessions, number of weeks, kind of control condition (2 = active control condition/attention placebo, 1 = wait list/care as usual), assessment of depression, assessment of anxiety, and change in depressive and anxiety symptoms at posttest and follow-up. If the participants had mental health problems as well as physical diseases, the former problems were used for categorizing the sample because the initial depressive and anxiety scores determine the maximum improvement of these symptoms. While the author coded all studies, a random sample of 30 studies was also coded by a research assistant with experience with meta-analyses. A mean inter-rater agreement of r = 0.87 was achieved for continuous variables and of 92% for categorical variables. Differences between the raters were resolved by discussion.

Statistical analysis

Calculations were performed with the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, using random-effects models and the method of moments (Borenstein et al., Citation2014).

Effect sizes d were computed as the difference between symptom change in the reminiscence condition and the control condition, divided by the pooled standard deviation at pretest (SD).

Outliers that were more than two SDs from the mean effect sizes were recoded to the value at two SD in order to limit their impact on the weighted effect size (Lipsey & Wilson, Citation2001).

Effect sizes were transformed to Hedges’ g which corrects for bias due to overestimation of the population effect size in small samples.

Weighted mean effect sizes and 95%-confidence intervals [CI] were computed. The significance of the mean was tested by dividing the weighted mean effect size by the standard error of the mean.

Homogeneity of effect sizes was analyzed with the Q statistic and I2 – the ratio of true heterogeneity to total observed variation.

Effects of moderator variables were analyzed with an analogue of an analysis of variance and meta-regression.

Finally, Egger’s regression test and trim-and-fill analysis were computed in order to check whether the results may have been influenced by publication bias. Egger’s test analyzes whether studies with smaller samples report larger effect sizes (as small studies with low, non-significant effect sizes may remain unpublished and not be found in literature search). The trim-and-fill algorithm imputes possibly missing results and estimates corrected mean effect sizes (Duval & Tweedie, Citation2000).

Results

The included studies provided data on 7,141 individuals who participated in different kinds of reminiscence interventions and on 7,324 participants of control conditions. The participants had a mean age of 70.54 years (SD = 12.91; range 20.80–88.36 years). About 59.1% of the participants were women. A total of 125 studies provided data on SR, 34 studies on LR, and 48 studies on LRT. Fifty-one studies included samples with elevated psychological symptoms (with 45 of them including individuals with elevated depressive symptoms), 45 studies focused on individuals with dementia or milder forms of cognitive impairment, and 37 studies focused on patients with a physical illness (15 of them on cancer patients in particular). Finally, 66 studies included samples that were not selected because of their elevated psychological symptoms, cognitive impairment or physical illness (although some of the participants might have had such conditions). Depressive symptoms were most often assessed with the Geriatric Depression Scale (Sheikh & Yesavage, Citation1986; 69 studies) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS, Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983; 21 studies). Anxiety was most often assessed with the HADS (23 studies) and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger et al., Citation1970; 10 studies).

With regard to study quality, a useful classification of biases distinguishes between selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias, detection bias and reporting bias (Higgins et al., Citation2022) and items from the ROB 2 tool (Sterne et al., Citation2019) were used for assessing bias. With regard to selection bias, the focus on RCTs minimized the risk of systematic differences between intervention and control condition. For participation, individuals had to be interested in reflecting on the past. Thus, results only apply to persons who are open to this. The outcome data were mostly based on self-reports and participants were not blinded about their group membership, thus indicating potential performance bias. Regarding intervention bias, most studies did not report the time each subject actively participated in the intervention studies. The average dropout rate was 13.3%, and dropout rates varied between studies from 0% to 54%, thus indicating varying risk for attrition bias. There was a minor risk for reporting bias as two studies had to be excluded because of not providing sufficient effect size information on change in depression.

Reminiscence interventions led, on average, to moderate improvements of depressive symptoms at posttest (g = 0.60) and follow-up about 24 weeks after the end of the intervention (g = 0.51; ). The effect sizes varied significantly between studies, and I2 indicates that between 70% and 80% of the variability is explained by differences between the included studies rather than by sampling error.

Table 1. Mean effects of reminiscence on depressive symptoms and effects of categorical moderator variables.

There were small-to-moderate improvements of anxiety symptoms at posttest (g = 0.44) and small improvements at follow-up (g = 0.23; ). Change in anxiety symptoms varied between studies and 70.6% of the variability at posttest and 53% of the variability at follow-up reflects true differences rather than sampling error.

Table 2. Mean effects of reminiscence on anxiety symptoms and effects of categorical moderator variables.

Based on the second research question, we first compared SR, LR, and LRT. Q-test identified significant differences between effects of these kinds of interventions at posttest. The non-overlap of the 95%-CI indicates stronger declines of depressive symptoms at posttest in studies on LRT than in studies on SR and LR (). Changes of depressive symptoms at follow-up did not vary between the kinds of reminiscence. Improvements of anxiety symptoms at posttest tended to be stronger in studies on LRT compared to studies on SR, but the 95%-CI overlapped (). Changes of anxiety symptoms at follow-up did not vary between the three kinds of reminiscence.

With regard to the third research question, effects of reminiscence on change in depressive symptoms were larger if the study focused on individuals with elevated psychological symptoms at pretest compared to studies with cognitively impaired individuals, persons with chronic physical illness, or studies from the general population (). At follow-up, improvements of depressive symptoms were stronger in studies on individuals with elevated mental health symptoms than in studies among individuals with cognitive impairment. In contrast, changes in anxiety symptoms did not vary between studies on persons with elevated psychological symptoms, cognitive impairment, physical illness, or persons who had not been selected because of such problems ().

Regarding the final research question, there were no moderating effects of residence and individual versus group setting. The latter result was replicated when restricting the studies to LR/LRT (Q(1) = 0.05 to 1.48, n.s.). However, improvements of depressive symptoms at posttest and anxiety at both times of measurement were larger if the studies used a passive control condition (wait list, treatment as usual) compared to an active control condition, such as discussions about actual events. Moderating effects of publication status were observed at posttest with stronger improvements of depressive and anxiety symptoms in published as compared to unpublished studies. When exploring whether intervention effects may vary between regions of the globe, we did not find RCTs from Africa and only two studies from Central/South America. Thus, regional comparisons were limited to the other regions of the globe. There was significant regional variation in change of depression and anxiety at posttest. Stronger improvements of depressive and anxiety symptoms were observed in studies from Asia as compared to studies from North America ( and ). The significant Q-score for regional differences in change of anxiety symptoms at follow-up was difficult to interpret as the 95%-CI overlapped.

There were no moderating effects of participants’ mean age and of percentage of female participants (). Finally, intervention effects on depressive symptoms were weaker in shorter interventions as measured by number of sessions and number of weeks. We checked whether these moderating effects may be based on confounders. LR/LRT consisted, on average, of fewer sessions than SR (F(2,217)=10.63, p < 0.001; LRT: M = 6.51 sessions, LR: M = 6.70, SR: M = 12.35). Similarly, the duration in weeks was lower in LRT/LR than in SR (F(2,213)=6.93, p < 0.001; LRT: M = 6.35 weeks, LR: M = 6.39, SR: M = 11.58). The same was the case when comparing effects on individuals with mental health problems and other individuals (number of sessions: F(1,218) = 9.44, p < 0.002, mental health problems: M = 6.74, others: M = 11.13; weeks: F(1,214) = 6.72, p < 0.01, mental health problems: M = 6.50, others: M = 10.53). Two additional meta-regressions were computed with change of depression at posttest as dependent variable and number of sessions or weeks, respectively, SR (1 = yes, 0 = no) and mental health problems at pretest (1 = yes, 0 = no) as independent variables. Moderating effects of number of sessions (β = -0.11, Z = -1.80, p < 0.08) and number of weeks (β = -0.08, Z = -1.24, p < 0.22) were no longer significant.

Table 3. Moderating effects of continuous variables.

As comparisons of results from published versus unpublished studies indicate publication bias, we searched for further hints with Egger’s regression test and trim-and-fill analysis. Egger’s test indicated that the size of change in depression and anxiety varied with the sample size or precision, respectively, of the individual study (t varied between t(56)=3.26, p < 0.004 for depressive symptoms at follow-up and t(204)=5.70, p < 0.001 for depressive symptoms at posttest). Trim-and-fill analysis added one possibly missing effect size in the analysis of change in depression and anxiety at posttest, but the mean effect sizes remained unchanged. No possibly missing effect sizes were added for change in depressive symptoms at follow-up. However, seven possibly missing effect sizes were added in the analysis of anxiety symptoms at follow-up. The re-estimated effect size declined and was no longer statistically significant (g = 0.09, 95%-CI −0.08 to 0.25, t(26)=1.05).

Discussion

The present meta-analysis found, on average, moderate improvements of depressive symptoms and small-to-moderate improvements of anxiety at posttest across all three types of intervention. While moderate improvements of depression persisted at follow-up, results were inconclusive regarding long-term effects on anxiety. Above-average improvements of depression and anxiety were found in LRT compared to LR and SR. Intervention effects varied, in part, by symptom level at pretest, intervention length, kind of control condition, publication status, and region.

The present meta-analysis adds to the evidence that reminiscence interventions reduce depressive and anxiety symptoms. While the moderate effect on depressive symptoms is similar to the effect reported by Al-Ghafri et al. (Citation2021), the present-meta-analysis is the first to analyze effects of reminiscence on anxiety symptoms when not limiting the focus on individuals with physical illness. Although improvement of anxiety symptoms seemed to be smaller than improvement of depressive symptoms, the 95%-CI overlapped, thus indicating more similarity than difference.

In line with three previous meta-analyses (Cuijpers et al., Citation2021; Ji et al., Citation2023; Westerhof & Slatman, Citation2019), we found strong improvements of depressive symptoms after participating in LRT at posttest. The two former meta-analyses even reported that effects of LRT on depression were slightly larger than the effects of other forms of psychotherapy. Nonetheless, RCTs would be needed that randomly assign individuals to different evidence-based interventions, but the number of studies comparing LRT against other evidence-based treatments is still low (Cuijpers et al., Citation2021; Ji et al., Citation2023).

The observed larger improvements after LRT compared to SR and, in part, LR are probably based on the fact that we coded interventions as LRT only if the initial levels of psychological symptoms were elevated, thus leaving more room for improvement compared to the other interventions. Stronger effects of LRT compared to SR may also be based on the larger number of processes working in LRT, and meaning (re)construction in particular (Hallford et al., Citation2019; Molinari, Citation2019). Although meaning (re)construction is a core component of (nontherapeutic) LR as well as LRT, participants of LRT may struggle more with their past as former negative experiences may be a source of the present symptoms (Westerhof et al., Citation2010). Thus, participants of LRT may benefit more from meaning (re)construction than participants of non-therapeutic LR. The similar effects of SR and LR (in nonclinical samples) indicate that either similar processes work in both kinds of intervention (such as affirmation from others or remembering good times) or that different processes associated either with SR (e.g. boredom reduction) and LR (e.g. meaning construction) lead to equivalent effects on mental health.

While previous meta-analyses mostly focused on a narrow-defined group of participants, such as individuals with dementia/cognitive impairment (Huang et al., Citation2015; Kim & Lee, Citation2019; Thomas & Sezgin, Citation2021) or physical illness (Chen et al., Citation2017), the present meta-analysis directly compared effects on different target groups. While short-term effects on depressive symptoms were strongest in individuals with elevated initial mental health symptoms, effects on individuals with cognitive impairment, physical illness, and the general population were highly similar, thus indicating that these groups benefit similarly from reminiscence interventions (although some group-specific adaptations of the contents have to be done). However, studies on cognitive impairment mostly referred to mild cognitive impairment and early stages of dementia when memory skills are sufficient to participate. The lack of significantly stronger improvement of anxiety symptoms in studies on individuals with elevated initial mental health problems may be due to the fact that these studies mostly selected persons with elevated depressive symptoms rather than anxiety symptoms.

Similar effects were found in institutionalized and non-institutionalized samples as well as in individual and group setting. Our results did not support the suggestion that the individual setting should be preferred in particular for LR/LRT as it provides a sense of safety when disclosing sensitive issues, and more time can be invested for each participant (Haight & Haight, Citation2007). However, Korte et al. (Citation2014) showed that the group LRT setting also offers unique conditions for promoting change, feeling accepted, realizing that others have problems too, learning from others, and being able to help others. As the individual and group setting offer conditions that promote change, effects on improvement of depressive and anxiety symptoms were rather similar across both settings. Nonetheless, the setting might play a role for other outcome variables, such as reducing loneliness. Intervention effects were stronger in studies that compared with a passive control group rather than an active control group, indicating that unspecific intervention effects (e.g. of socializing or attention from the interventionist) reduce the size of differences between changes during reminiscence and in active control conditions.

We can only speculate about reasons for above-average effects of reminiscence in Asian studies as compared to studies from North America or Europe. As Asian individuals often tend to situate their perceived problems in the larger context of their life history (Ino & Glicken, Citation2002), LR is a culturally highly appropriate intervention. In addition, solving biographical conflicts related to close social ties promotes perceived social harmony that is highly valued in Asian societies (Markus & Kitayama, Citation1999). Furthermore, Xiao (Citation2011) suggested that individuals from China may strongly benefit from reminiscence because alternative psychosocial interventions are unavailable. This argument may be generalized to other Asian countries.

The lack of moderating effects of age and gender indicates that younger and older adults as well as men and women benefitted to a similar extent. As moderating effects of intervention length were based on confounding effects of third variables, duration had no independent explanatory value. However, two thirds of the interventions offered 6 to 12 sessions over 6 to 12 weeks, thus indicating variance restriction. As numbers of studies were too small for interventions with less than 6 sessions for drawing reliable conclusions, we conclude that 6 sessions would be sufficient producing moderate improvement of depressive symptoms.

We found some evidence for a possible publication bias, and trim-and-fill analysis indicates that results on change of anxiety symptoms at follow-up have to be interpreted with caution. However, asymmetric funnel plots—that are corrected with trim-and-fill analysis—do not only emerge in the case of publication bias. They are also found if studies with smaller samples differ from those with larger samples in characteristics that affect the size of observed effects (Page et al., Citation2021). As, for example, studies on LRT had, on average, fewer participants in the intervention condition than studies on SR (n = 24 vs. n = 36, F(1, 176) = 5.62, p < 0.02), the detected funnel plot asymmetry might have been on this difference rather than on publication bias.

Limitations and conclusions

Some limitations of the present study have to be mentioned. First, the number of studies on change of anxiety symptoms at follow-up was limited, leading to lower test power than in the other analyses. Second, we used quantitative measures of the frequency and/or severity of symptoms of anxiety and depression, rather than clinical diagnoses. Thus, we could not identify remission rates of patients with initial depressive and anxiety disorders. Third, most of the included studies focused on older adults, thus reducing the chance of detecting age differences in reminiscence effects. Fourth, comparisons across geographical regions did not include Africa and Central/South America. Most of the Asian studies had been conducted in Chinese-speaking countries and Iran. Thus, these data do not represent the full range of Asian countries. Similarly, studies from Eastern Europe were lacking. Fifth, as we addressed only two outcome variables, we could not analyze the complete range of possible effects. Finally, as information on the profession and training in reminiscence of the interventionists was lacking in most studies, we could not test for moderating effects of these characteristics.

Despite these limitations, the following conclusions can be drawn. First, given the large number of RCTs and the average effects on depressive and anxiety symptoms, we conclude that reminiscence interventions are evidence-based and can be recommended for adults with elevated psychological symptoms, physical illness, cognitive impairment (as long as cognitive and verbal abilities allow to participate) as well as for individuals in general who are interested in reflecting on their past.

Given the lack of age differences in the effects of reminiscence, we conclude that reminiscence is more than a useful tool for only older adults as originally thought (Butler, 1974) and it could be offered for adults of all ages who are willing to reflect on their past. The similar effects of reminiscence in the individual and (small) group format indicates that both formats are equally recommended, although some individuals may prefer the one over the other format.

Regarding future research needs, it would be interesting to empirically compare the levels of the different reminiscence functions (e.g. boredom reduction, social affirmation) across SR, LR and LRT, and to analyze whether fulfillment of these functions produces similar or different effects across the different forms of reminiscence. Given the small numbers of available studies and the results of trim-and-fill analysis, we also recommend more studies on long-term effects of reminiscence on anxiety symptoms for drawing clear conclusions on the long-term effect of reminiscence on these symptoms. In addition, to get a comprehensive picture of reminiscence effects around the globe, more research on the effects of reminiscence from African and Central/South American countries is recommended. For increasing study quality, researchers should provide more differentiated data on participation (e.g. number of sessions attended) and add data from raters who are blind of group membership.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (89.6 KB)Disclosure statement

The author(s) report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

Relevant data of the included studies are provided in the electronic supplement.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Al-Ghafri, B. R., Al-Mahrezi, A., & Chan, M. F. (2021). Effectiveness of life review on depression among elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Pan African Medical Journal, 40(1), 168. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2021.40.168.30040

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. (2014). Comprehensive meta-analysis: A computer program from research synthesis (Version 3). Biostat.

- Chen, Y., Xiao, H., Yang, Y., & Lan, X. (2017). The effects of life review on psycho-spiritual well-being among patients with life*threatening illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(7), 1539–1554. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13208

- Cuijpers, P., Quero, S., Noma, H., Ciharova, M., Miguel, C., Karyotaki, E., Cipriani, A., Cristea, I. A., & Furukawa, T. A. (2021). Psychotherapies for depression: A network meta-analysis covering efficacy, acceptability and long-term outcomes of all main treatment types. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 20(2), 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20860

- Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x

- Elias, S. M. S., Neville, C., & Scott, T. (2015). The effectiveness of group reminiscence therapy for loneliness, anxiety and depression in older adults in long-term care: A systematic review. Geriatric Nursing (New York, N.Y.), 36(5), 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.05.004

- Esmaeili, M., & Usefynezhad, A. (2016). Effectiveness life review on life satisfaction among adolescents under the supervision of Qazvin Well-Being Center. Open Journal of Psychiatry, 06(01), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpsych.2016.61001

- Haight, B. K., & Haight, B. S. (2007). The handbook of structured life review. Health Professions Press.

- Hallford, D. J., Mellor, D., & Burgat, M. E. (2019). A qualitative study of young adults’ experience with a reminiscence-based therapy for depressive symptoms. Emerging Adulthood, 7(4), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696818769175

- Higgins, J. P. T., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., & Sterne, J. A. C. (2022). Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Available online at https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current (accessed 2023-06-06)

- Hofer, J., Busch, H., Au, A., Poláčková Šolcová, I., Tavel, P., & Tsien Wong, T. (2020). Reminiscing to teach others and prepare for death is associated with meaning in life through generative behavior in elderlies from four cultures. Aging & Mental Health, 24(5), 811–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1548568

- Huang, H. C., Chen, Y. T., Chen, P. Y., Hu, S. H. L., Liu, F., Kuo, Y. L., & Chiu, H. Y. (2015). Reminiscence therapy improves cognitive functions and reduces depressive symptoms in elderly people with dementia: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 16(12), 1087–1094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2015.07.010

- Ino, S. M., & Glicken, M. D. (2002). Understanding and treating the ethnically Asian client. Journal of Health & Social Policy, 14(4), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1300/J045v14n04_03

- Ji, M., Sun, Y., Zhou, J., Li, X., Wei, H., & Wang, Z. (2023). Comparative effectiveness and acceptability of psychotherapies for late-life depression: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 323, 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.11.089

- Kim, K., & Lee, J. (2019). Effects of reminiscence therapy on depressive symptoms in older adults with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis [in Korean]. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 49(3), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2019.49.3.225

- Korte, J., Drossaert, C. H., Westerhof, G. J., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2014). Life review in groups? An explorative analysis of social processes that facilitate or hinder the effectiveness of life review. Aging & Mental Health, 18(3), 376–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.837140

- Korte, J., Westerhof, G. J., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2012). Mediating processes in an effective life-review intervention. Psychology and Aging, 27(4), 1172–1181. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029273

- Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Sage.

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1999). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), The self in social psychology (pp. 339–371). Psychology Press.

- Molinari, V. (2019). Commentary on “In search of the best evidence for life review therapy to reduce depressive symptoms in older adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials”: Some thoughts on how life review reminiscence therapy can inform clinical theory and practice for both younger and older adults. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 26(4), e12304. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12304

- Page, M. J., Higgins, J. P. T., & Sterne, J. A. C. (2021). Assessing risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis. In J.P.T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M.J. Page, & V.A. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Version 6.2., pp. 205–228)

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1080/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Pinquart, M., & Forstmeier, S. (2012). Effects of reminiscence interventions on psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis. Aging & Mental Health, 16(5), 541–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2011.651434

- Rosenthal, R. (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 638–641. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638

- Sheikh, R. L., & Yesavage, J. A. (1986). Geriatric depression scale (GDS). Clinical Gerontologist, 5(1-2), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1300/J018v05n01_09

- Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., & Lushene, R. E. (1970). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Sterne, J. A. C., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., Blencowe, N. S., Boutron, I., Cates, C. J., Cheng, H.-Y., Corbett, M. S., Eldridge, S. M., Emberson, J. R., Hernán, M. A., Hopewell, S., Hróbjartsson, A., Junqueira, D. R., Jüni, P., Kirkham, J. J., Lasserson, T., Li, T., … Higgins, J. P. T. (2019). RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 366, l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

- Sun, J., Jiang, J., Wang, Y., Zhang, M., Dong, L., Li, K., & Wu, C. (2023). The efficacy of reminiscence therapy in cancer-related symptom management: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 22, 15347354221147499. https://doi.org/10.1177/15347354221147499

- Tam, W., Poon, S. N., Mahendran, R., Kua, E. H., & Wu, X. V. (2021). The effectiveness of reminiscence-based intervention on improving psychological well-being in cognitively intact older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 114, 103847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.10384

- Thomas, J. M., & Sezgin, D. (2021). Effectiveness of reminiscence therapy in reducing agitation and depression and improving quality of life and cognition in long-term care residents with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatric Nursing (New York, N.Y.), 42(6), 1497–1506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.10.014

- Westerhof, G. J., & Slatman, S. (2019). In search of the best evidence for life review therapy to reduce depressive symptoms in older adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 26(4), e2301–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12301

- Westerhof, G. J., Bohlmeijer, E., & Webster, J. D. (2010). Reminiscence and mental health: A review of recent progress in theory, research and interventions. Ageing and Society, 30(4), 697–721. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X09990328

- Xiao, H. (2011). Development and evaluation of a life review program for Chinese advanced cancer patients (Unpublished dissertation). Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

- Yan, Z., Dong, M., Lin, L., & Wu, D. (2023). Effectiveness of reminiscence therapy interventions for older people: Evidence mapping and qualitative evaluation. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 30(3), 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12883

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716x