Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the variables that were associated, contributed and moderated quality of life (QoL) and burden in family caregivers.

Methods

A total of 130 participants were evaluated using the following instruments: Depression, Anxiety and Distress Scale; Index of Family Relations; Heartland Forgiveness Scale; Burden Interview Scale; Short Form Health Survey.

Results

Being a younger caregiver, less distress, better family relationships and greater use of forgiveness were associated with more QoL. Also, family caregivers who chosethe caregiving role, less distress, better family relationships and greater use of forgiveness showed lower levels of burden. Age, distress and forgiveness contributed to QoL. In turn, the choice to become a family caregiver, distress, and forgiveness contributed to burden. Forgiveness played a moderating role in the relationship between family relationships and burden.

Conclusion

Based on the results, there is a need to intervene in older family caregivers, particularly those who did not choose to become a caregiver, who report greater distress, have worse family relationships, and display less use of forgiveness, in order to decrease their burden and promote QoL.

Introduction

About 50 million people worldwide are believed to have some form of dementia, with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia being the most common one, accounting for approximately 60 to 70% of cases (World Health Organization, Citation2017). Worldwide, AD is one of the main causes of dependence and disability among the elderly (Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2021).

Due to the deteriorating and disabling nature that characterize dementias, and in particular AD dementia, there is a growing need for a caregiver to help with the patient’s day-to-day needs (Alzheimer Europe, Citation2019; Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2021). This type of care is usually given informally (Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2021) and is most regularly performed by women, with some type of kinship with the AD patient, most commonly spouses and daughters (Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2021). About 1/3 of family caregivers are 65 years of age or older and, on average, spend approximately three hours a day caring, and more than half of those caregivers have provided this type of care for more than four years (Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2021). In Portugal, caregiving is commonly given by a family member that often takes on this role for several reasons such as the feeling of obligation driven by social norms; a sense of ‘giving back’; emotional ties; sense of duty; compassion; coerced altruism; or altruistic motives (Costa et al., Citation2019; Pope et al., Citation2017).

Due to the increasing dependence of dementia patients on family caregivers for basic daily activities, the family assumes a pivotal role in the care provided. The caregiver role requires a restructuring of family dynamics to meet the evolving needs of the patient (Lindeza et al., Citation2020; Luiu et al., Citation2020). Consequently, the family member taking on the caregiving role undergoes a transformative process that may introduce some tension in the relationship with the family (Galvin, Citation2013). Maintaining the quality of the family relationship is crucial in the dementia care context as it may function as a base for emotional support, more effective communication and decision-making , more wellbeing for both the caregiver and the AD patient, and a more adapted caregiving environment (Farina et al., Citation2017; Hazzan et al., Citation2022). Research suggests a critical interplay between the quality of family relationships and both the quality of life (QoL) and burden experienced by family caregivers. Family functioning issues, such as communication, cohesion, and the allocation of responsibilities, are significantly associated with symptoms of depression and stress (Sutter et al., Citation2014). Given that caregiving is often a solitary endeavor and seeking assistance may be perceived as a personal shortcoming, family caregivers may struggle with great distress, over time. The distress may subsequently lead to deteriorating family relationships, lower QoL, and an increased sense of burden (Lindeza et al., Citation2020; Luiu et al., Citation2020).

The act of caring for a patient with dementia may be considered a chronic stressor, with a stable pattern of perceived distress over time in the family caregiver (Borsje et al., Citation2016). The literature shows that the distress experienced by the caregiver is associated with an aggravation of the patient’s dementia condition (Mank et al., Citation2023; Stall et al., Citation2019, Välimäki et al., Citation2016) and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (e.g. irritability, aggression/agitation, delusion) may also result in feelings of frustration and anger, in the caregiver. Studies also indicate that the greater the distress experienced, the worse family relationships were considered (Pereira et al., Citation2021), and greater perceived burden (Liu et al., Citation2017) was also associated with lower caregiver’s QoL (Quinn et al., Citation2020).

To deal with the stress associated with caregiving, coping strategies are believed to play a pivotal role in how the stress is perceived and experienced (Pearlin et al., Citation1990). Hence, it is crucial to explore coping mechanisms that may mitigate the impact of caregiver stressand play a moderating role. One such emotion-focused coping strategy is forgiveness, defined as an intra- and interpersonal process involving the cultivation of positive emotions to alleviate the stress response (Worthington & Scherer, Citation2004). Caring for an AD patient poses considerable challenges for family caregivers, and studies indicate that up to one-third of family caregivers experience some form of abuse (e.g. psychological abuse) from the person they are caring for (Steinsheim et al., Citation2022). In situations where hurt or disappointment arises, forgiveness becomes a tool to preserve the quality of the relationship, becoming a transformative process regarding thoughts, behaviors, and emotions that change from negative into positive (Strelan, Citation2018). It is essential to clarify that forgiveness does not necessarily imply tolerating or forgetting the reasons behind transgressions; rather, it involves a conscious decision to release negative emotions and enhance one’s own well-being, thereby contributing to healthy relationships (Worthington & Scherer, Citation2004). According to Thompson et al. (Citation2005), when the act of forgiveness happens, the individual reassesses the transgression and experiences a shift in the perception of the wrongdoing. This response involves two key aspects, each subject to change: a) valence, pertaining to whether thoughts, feelings, or behaviors are negative, neutral, or positive, and b) strength, relating to the intensity and intrusiveness of the response. Therefore, the individual has the capacity to change the negative response triggered by the transgression by either converting the valence from negative to neutral or positive, or by modifying both the valence and the strength of the response.

Given the chronic nature of caregiver stress, forgiveness holds particular significance as it is instrumental in preserving the family relationship, particularly in situations involving behavioral and emotional changes in the patient being cared for (DeCaporale-Ryan et al., Citation2016). Which, in turn, is essential for ensuring the adequacy of care provided. Additionally, family caregivers themselves may struggle with feelings of self-perceived inadequacy, guilt associated with seeking help, or engaging in self-care behaviors (Cheng et al., Citation2013). In such contexts, forgiveness emerges as a valuable tool for promoting emotional well-being and maintaining the overall health of caregiver relationships.

The literature on the role of forgiveness in family caregivers in stress management is still limited, but some studies indicate that the greater the use of forgiveness as a coping strategy, the lower the marital distress (DeCaporale-Ryan et al., Citation2016), the higher the quality of family relationships, and the lower the state anxiety, depressive symptomatology and burden (Cheng et al., Citation2013; Rasmussen et al., Citation2019). The recurrent use of forgiveness may be a negative predictor of burden in family caregivers (Cheng et al., Citation2013). Rasmussen et al. (Citation2019) highlighted the buffering role of forgiveness in mitigating the adverse effects of stressors on health, revealing a positive association between the practice of forgiveness and both physical and mental health. The authors suggested that forgiveness could positively impact physical symptoms such as heart rate and have a negative effect on psychological symptoms such as stress, anxiety, and depression. However, research that focuses on the moderating role of forgiveness as a coping strategy in family caregivers is still scarce. Hence, it becomes important to investigate the moderating role of forgiveness in the relationship between family relationships/distress and QoL/burden.

Caregiver burden is a complex concept that was defined by Kasuya et al. (Citation2000) as being ‘a multidimensional response to physiological, emotional, social and financial stressors associated with the caregiving experience (p. 119). Literature consistently reports that caring for a patient with AD is linked with high burden (Nemcikova et al., Citation2023; van den Kieboom et al., Citation2020), and being a family caregiver is associated with greater burden compared to non-caregivers (Pinquart & Sörensen, Citation2003). More perceived burden has been associated to several factors such as the length of the duration of care (Lethin et al., Citation2020), the number of hours of care (Yu et al., Citation2015), and not choosing the act of caring (Pertl et al., Citation2019). Additionally, the literature shows that caregiver burden is positively related with perceived distress (Liu et al., Citation2017), and negatively related with the quality of family relationships (Yu et al., Citation2015), the use of positive coping strategies (Kazemi et al., Citation2021) and QoL (Abdollahpour et al., Citation2015).

Being a caregiver of a patient with AD may impact several domains of the caregiver’s life, impacting QoL (Pereira et al., Citation2021). The concept of QoL in family caregivers, as explained by Farina et al. (Citation2017), is influenced by numerous factors. Family caregivers often experience a worse QoL compared to the general population (Välimäki et al., Citation2016) and family caregivers of patients with other chronic diseases (Karg et al., Citation2018). Factors such as age, and not choosing the caregiving role (Pereira et al., Citation2021), longer duration of care (Farina et al., Citation2017), greater perceived distress (Välimäki et al., Citation2016), worse family relationships (Lindeza et al., Citation2020), less use of positive coping strategies (Rodríguez-Pérez et al., Citation2017) and greater perceived burden (Lethin et al., Citation2020) have been associated with worse QoL.

While the existing literature extensively explores the impact of psychological variables on caregiver burden and QoL (e.g. Chiao et al., Citation2015; Farina et al., Citation2017), there remains a gap on how coping strategies, particularly forgiveness, may play a moderating role and contribute to lower burden and better QoL in family caregivers (Rasmussen et al., Citation2019). Forgiveness, beyond contributing to improved family relationships and reduced caregiver stress (Cheng et al., Citation2013; Rasmussen et al., Citation2019), also showed a positive impact on physical health (Rasmussen et al., Citation2019). Therefore, studying forgiveness in family caregivers experiencing high daily stress, especially those seeking to preserve relationships with the AD patient, is crucial. This study aims to provide valuable insights to develop interventions that address the specific needs of the family caregiver population, to ultimately promote better QoL and reduced burden.

The Stress Process Model was developed by Pearlin et al. (Citation1990) and is currently a reference in family caregivers as one of the few specific models for this population being widely used (e.g. Pereira et al., Citation2021). The model proposes that stress is a process that includes four domains: 1) the background/context of the caregiver (e.g. age, gender, type of dementia); 2) the stressors related to the act of caregiving, that may be primary stressors (i.e. directly associated with the act of caring) and secondary stresses (i.e. that are the result of primary stressors); 3) the outcomes or manifestations of stress, which are the consequence of the previous domains; and 4) the mediators/moderators that impact the relationship between the variables involved in the process. Although in the original version, burden is considered a primary stressor, in this study it will be used as an outcome, like other studies have done (Roland & Chappell, Citation2019). Using a modified version of the proposed theoretical model and in order to fill the current gaps in the literature in family caregivers of patients with AD, the present study aims to: 1) evaluate the relationship between sociodemographic and psychological variables with QoL and caregiver burden; 2) to assess the contribution of sociodemographic and psychological variables to QoL and caregiver burden; and 3) to assess the moderating role of forgiveness as a coping strategy between secondary stressors (i.e. distress and family relationships) and QoL/burden. Thus, in order to answer the goals of the present study, the following hypotheses were formulated: H1: It is expected that , being older, longer duration of care, greater daily number of hours of care, not choosing the role of caregiver and greater perceived distress will be negatively associated with QoL and positively associated with burden, while greater forgiveness and better family relationships will be positively associated with QoL and negatively associated with burden; H2: It is expected that younger age, shorter duration of care, less hours of caregiving per day, choice of caregiving, less perceived distress, good family relationships and greater use of forgiveness will contribute to a better QoL and lower burden H3: Forgiveness is expected to play a moderating role in the relationship between secondary stressors and QoL/burden.

Method

Participants and procedure

Family caregivers were recruited through the Research-Action Dementia Project using a convenient sample. Inclusion criteria were: a) being a caregiver of a patient with AD; b) being 18 years old or above; and c) being in the caregiving role for at least three months. Exclusion criterion included: a) caring for an institutionalized patient with AD and b) receiving psychological support. Data collection was carried out in a home context and included users of the Portuguese National Health System diagnosed with dementia in the Northern region of Portugal. Out of 175 family caregivers invited, 8 did not agree to participate and 37 did not meet the criteria for the study. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research in Social and Human Sciences (CEICSH/0462020) from a major University in Northen Portugal.

Measures

Participants answered the following instruments that were validated for the Portuguese population:

Heartland Forgiveness Scale (HFS; Thompson et al., Citation2005) is an 18-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess the general tendency toward forgiveness (i.e. dispositional forgiveness) of others, oneself, and situations, through items of positive and negative valence. Scores range between 18 and 126, with higher scores indicating higher use of forgiveness. The original version showed an alpha for the total scale of .86 and in this study the alpha was .85. and the omega .87.

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale – Short Form (DASS21; Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995) is a 21-item self-report instrument that assesses emotional states associated with depression, stress and anxiety. Scores range from zero to 63 and higher values indicate greater anxiety, depression and stress. The original version showed an alpha of .93 for the global scale (Henry & Crawford, Citation2005) and, in this study, the alpha and omega were both .97.

The Index of Family Relations (IFR; Hudson, Citation1993) is a self-report instrument that assesses problems of social and personal functioning in the context of family adjustment, where the score can vary between zero and 100 points, and higher values indicate greater family stress. The original version showed an alpha of .95 and in this study, the alpha was .81 and the omega .90.

Burden Interview Scale (BIS; Zarit & Zarit, Citation1983) is a self-report instrument that assesses the caregiver’s subjective and objective burden in 22 items. Scores range from zero to 88, where higher values indicate greater subjective and objective burden. The original version showed an alpha of .84. and, in this study, the alpha and omega were both .94.

Short Form Health Survey (SF-36; Ware et al., Citation1993) is a self-report instrument that assesses two dimensions of QoL (i.e. physical health and mental health) through 8 components, namely physical performance, physical, pain, mental health, general health status, vitality, mental performance and social function. It has 36 items distributed in questions with Likert and dichotomous scales. The instrument has a score that varies between zero and 100 points and higher values in the physical/mental dimension indicate a better functioning of physical/mental health. The original version showed an alpha of .94 for the total scale (Guermazi et al., Citation2012) and in this study, the alpha was .94 and the omega .99.

Data analysis

The data obtained was analyzed using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28. The database included no missing data since participants answered the instruments in an interview format and no outliers were found. To evaluate the relationships between the variables (H1) a Pearson correlation test was used and the Point-Bisseral coefficient. To understand which variables contributed to the caregiver’s QoL (H2), a hierarchical linear regression (enter method) was performed. Finally, to assess the moderating role of forgiveness as coping strategies (H3), the Macro PROCESS command version 3.4.1 was used for SPSS and the Johnson-Neyman technique (Johnson & Fay, Citation1950) was employed. All the assumptions for moderation were present except when testing the relationship between distress and QoL/burden since distress (independent variable) showed a very high correlation (>0.50) with forgiveness (moderator variable), violating the assumption.

The Johnson-Neyman technique allows a precise computation of conditions and boundaries, showing the instances where a moderator elicits statistically significant slopes (Bauer & Curran, Citation2005).

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample of this study consisted of 130 Portuguese family caregivers of patients with AD. The characterization of the sample is shown in .

Table 1. Sociodemographic characterization of family caregivers of patients with AD.

Variables associated with QoL and burden

Regarding the sociodemographic variables, the correlation test showed that the older the family caregiver, the worse the QoL. Also, family caregivers who did not choose to be a caregiver, reported more burden.

Regarding psychological variables, the results indicated that the greater use of forgiveness was associated with better family relationships; less perceived distress, better QoL and less caregiver burden. In addition, greater use of forgiveness wasassociated with better family relationships and lower perceived distress. Finally, better family relationships were associated with lower perceived distress. The results are shown in .

Table 2. Relationship between sociodemographip and psychological variables.

Contributing variables to QoL and burden

In model 1, the contribution of sociodemographic variables to QoL was analyzed. The model indicated that family caregiver’s age contributed significantly to QoL, explaining 8% of the total variance. When adding the psychological variables (model 2), family relationships, perceived distress and the use of forgiveness, the total explained variance of the caregiver’s QoL increased to 42.6%. In this model, age, the use of forgiveness and perceived distress contributed significantly to QoL, while family relationships did not.

Model 3 tested the contribution of sociodemographic variables to burden and indicated that the choice to be a family caregiver explained 10.9% of caregiver burden. When psychological variables were added (model 4), the choice to be a caregiver, distress and forgiveness contributed to caregiver burden, explaining 52.1% of caregiver burden (R2 = 0.521), while family relationships showed no contribution ().

Table 3. Variables that contribute to quality of life and burden.

The moderating role of forgiveness

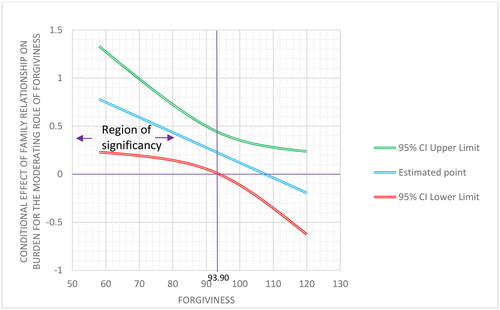

When testing the moderating role of forgiveness in the relationship between family relationships and QoL, no significant results were found (β = 0.0048, 95% CI [−0.0083, 0.0180], t = 0.7308, p = 0.4663). However, the model that tested the moderating role of forgiveness in the relationship between family relationships and burden was significant (F (3.126) = 26.3708, p = 0.0000, β = −0.0157, t = −2.1908, CI [−0.0299, −0.0015] p = 0.0303) and explained 38.57% of the variance. The Johnson-Neyman technique indicated that family relationships were significantly correlated with burden when the standardized value of forgiveness was93.90 above the mean (β = 0.2158, p = 0.0500), corresponding to 53.08% of the sample ().

Figure 1. Moderating role of forgiveness in the relationship between family relationship and burden.

The moderating role of forgiveness in the relationship between distress and QoL/burden could not be tested, as the moderation assumptions were not met as described in the data analysis.

Discussion

The study findings revealed a significant association between family caregivers’ age and their QoL. These results are in accordance with the literature that suggests a negative correlation between age and QoL (Pereira et al., Citation2021). A plausible explanation for this outcome may have to do with the aging process being responsible for a gradual decline in family caregivers’ health such as the possible onset of chronic conditions, impacting their QoL (Fagerström et al., Citation2020). However, age was not significantly associated with burden, which contrasts with the literature that i shows that being older is associated with more perceived burden (Kim et al., Citation2012). One possible explanation for this result is that age may not be linearly associated with burden, that is, different levels of burden might manifest at several stages of the caregiving process, over time (Chiao et al., Citation2015). This same author states that the act of caregiving is a complete and dynamic process in which other factors, regardless of the caregiver’s age , such as having previous experience as a caregiver or responsibility beyond the act of caring, may explain different patterns of the care burden response. For instance, being younger might be associated with greater perceived burden due to inexperience in caregiving, having other responsibilities such as having a full-time job, having small children or even having more financial strains. Over time, the burden could decrease as the family caregiver adapts more effectively to the demands of the caregiving tasks as a result of more experience, being retired, or having no other caregiving roles (e.g. caring for the offspring).

In this study, no significant associations were found between the number of hours of caregiving and the duration of care with both QoL and burden. However, the literature indicates that the number of hours and duration of care are negatively associated with QoL (Farina et al., Citation2017; Pereira et al., Citation2021) and positively associated with burden (Lethin et al., Citation2020; Yu et al., Citation2015). The number of hours of caregiving, in this study, was assessed by asking whether caregiving tasks took up or less than 12 h or more per day, and a possible explanation for these results might be the fact that 94.6% of the sample spent most of their day caring for the patient with AD and, therefore, was not possible to test whether the increase or decrease in the number of hours was related to the burden and QoL. Future studies may need to assess number of hours is a more incremental manner.

On one hand, not choosing the act of caregiving was associated with greater burden, what is in accordance with the literature since. when family caregivers feel they have chosen to become a caregiver, they are more likely to identify positive aspects related to the caregiving role, which potentially may lead to less perceived burden (Pertl et al., 2019). On the other hand, the choice of the act of caregiving was not significantly associated with QoL. One possible explanation for this result could be the fact that QoL was assessed using a generic QoL instrument, which may lack sensitivity to specific caregiving issues (e.g. item 3e: Does your health now limit you in climbing one flight of stairs?). Future studies could explore this result further using a specific instrument designed for family caregivers of patients with AD.

In this study, a positive relationship was identified between family relationships and burden, while a negative relationship was observed between family relationships and QoL. In other words, as the quality of family relationships declines, caregiver burden tended to increase, and conversely, when the quality of family relationships improves, QoL also tended to increase. These findings are consistent with the existing literature, indicating that family caregivers who reported positive family relationships experienced lower perceived burden and higher QoL (Lindeza et al., Citation2020). This association may be linked to the perception of greater support from the family towards the caregiving role.

Distress, in this study, was positively associated with burden and negatively associated with QoL. These finding is in accordance with previous studies which indicate that the greater the perceived distress, the greater the burden (Messina et al., Citation2022) and the lower the QoL (Pereira et al., Citation2021; Quinn et al., Citation2020). Consequently, symptoms of anxiety, depression and stress may be associated with caregiver’s deficits in the physical, mental, and social functioning, which may impact their QoL (Farina et al., Citation2017). These deficits may also lead to a greater impairment in the family caregiver’s role, which in turn, may contribute to a greater caregiver’s burden (Chiao et al., Citation2015).

The use of forgiveness was positively associated with QoL and negatively associated with burden. Rey and Extremera (Citation2016) and DeCaporale-Ryan et al. (Citation2016), found that individuals who used forgiveness experienced lower perceived burden and higher QoL. Forgiveness may work as a coping strategy that buffers the perception of stress, when caring for a patient with AD, reducing the perceived subjective burden and, as a result, increasing the perception of a better QoL, in the family caregiver.

In this study, age, perceived distress, and the use of forgiveness emerged as significant contributors to QoL, following previous research on the influence of age on perceived distress (Pereira et al., Citation2021), and the use of forgiveness as a coping strategy (Gull & Rana, Citation2013) on QoL. This result underscores the significance of both the contextual/background aspects and the psychological factors in shaping family caregiver’s QoL. Contrary to what was hypothesized, however, family relationships did not significantly contribute to caregiver’s QoL. Existing literature suggests that when family relationships predict QoL, problematic family relationships are associated with a decline in perceived QoL (Lindeza et al., Citation2020). One possible explanation for these unexpected results could be attributed to the remarkably low scores recorded in the IFR instrument showing that family caregivers reported a very low level of family stress. Consequently, the lack of variability in the sample may have prevented a discernible relationship between the quality of family relationships and QoL.

Consistent with previous studies, the variables that significantly contributed to burden were the choice of the act of caregiving (Pertl et al., 2019), perceived distress (Liu et al., Citation2017) and the use of forgiveness (Cheng et al., Citation2013). Literature shows that problematic family relationship significantly predict burden (Luiu et al., Citation2020). However, in this study, family relationship did not contribute to caregiver burden, probably for the same reason that family relationship did not contribute to QoL i.e. the low family stress reported by the sample.

The results revealed that forgiveness moderated the relationship between family relationships and burden. Specifically, when the family caregiver showed lower levels of forgiveness, the relationship between worse family relationships and greater burden was stronger. Thus, forgiveness may assume a mitigating or buffering role in the interplay between family relationships and burden. The literature supports the notion of forgiveness as a moderating variable, as evidenced in several populations such as family and friends of people who died by suicide (Levi-Belz & Gilo, Citation2020), patients with kidney disease on hemodialysis (Ye et al., Citation2019) and patients with psoriasis (Thompson, Citation2003). The moderating role of forgiveness is considered a coping strategy, playing a crucial role in preserving the quality of family relationships and reducing the perceived stress directly associated with caregiving. As a coping strategy, forgiveness, in turn, may alleviate the relationship between family relationships and caregiver burden (Campbell et al., Citation2008; Cheng et al., Citation2013). However, contrary to expectations, forgiveness was not a moderator in the relationship between family relationships and QoL. This outcome may have to do with the instrument used to assess QoL, the SF-36, that may be too generic and not sensitive enough to assess issues related to caregiving that may impact QoL while the instrument to assess burden (BIS) was specific for caregivers.

The theoretical model by Pearlin et al. (Citation1990) was an adequate model to assess QoL and burden in this sample of family caregiver patients with AD. In fact, forgiveness was a moderator between family relationships and burden, as suggested by the model. Based on the results, it would be important to develop intervention programs, focused on forgiveness, to increase QoL and reduce the burden, in this population.

Limitations and future implications

The present study has limitations that are important to consider such as the cross-sectional design that does not allow causal relationships, the low level of family caregiver’s education, the use of only self-report instruments and the fact that all participants lived in the same municipality. Future studies should follow a longitudinal design, include family caregivers from other regions of the country , and include also family caregivers with higher education. Qualitative studies are also important to analyze in more depth, dimensions that are limited by the quantitative nature of the instruments used, namely forgiveness of others and oneself, in the context of providing care to a family member.

Finally, it will be important in the future, to focus on the role of forgiveness as a mediator between caregiver burden and QoL, over time, as AD progresses. Another pertinent issue that is important to address and explore is the role of patient’s forgiveness towards their family caregivers when they feel they are not being well taken care.

Conclusion

This study focused on QoL and burden in family caregivers of AD patients. Considering the results, it would be essential that health professionals when assessing the patient also include the caregiver, especially older family caregivers who did not choose the caregiver role. Given the moderating role of forgiveness in the relationship between family relationships and burden, it is important that interventions include forgiveness as a coping mechanism for the family caregiver, other family members and the patient as well. The authos also believe that mental health professionals when promoting forgiveness, , should also address emotion regulation skills (e.g. reduction in resentment), relationship dynamics (e.g. communication), self-care, and better acceptance of the caregiving role.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdollahpour, I., Nedjat, S., Salimi, Y., Noroozian, M., & Majdzadeh, R. (2015). Which variable is the strongest adjusted predictor of quality of life in caregivers of patients with dementia?: QOL predictors in dementia caregivers. Psychogeriatrics, 15(1), 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12094

- Alzheimer Europe. (2019). Dementia in europe yearbook 2019: Estimating the prevalence of dementia in Europe. https://www.alzheimereurope.org/content/download/195515/1457520/file/FINAL%2005707%20Alzheimer%20Europe%20yearbook%202019.pdf

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2021). 2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 17(3), 327–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12328

- Bauer, D. J., & Curran, P. J. (2005). Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: Inferential and graphical techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 40(3), 373–400. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5

- Borsje, P., Hems, M. A. P., Lucassen, P. L. B. J., Bor, H., Koopmans, R. T. C. M., & Pot, A. M. (2016). Psychological distress in informal caregivers of patients with dementia in primary care: Course and determinants. Family Practice, 33(4), 374–381. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmw009

- Campbell, P., Wright, J., Oyebode, J., Job, D., Crome, P., Bentham, P., Jones, L., & Lendon, C. (2008). Determinants of burden in those who care for someone with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(10), 1078–1085. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2071

- Cheng, S.-T., Ip, I. N., & Kwok, T. (2013). Caregiver forgiveness is associated with less burden and potentially harmful Behaviors. Aging & Mental Health, 17(8), 930–934. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.791662

- Chiao, C.-Y., Wu, H.-S., & Hsiao, C.-Y. (2015). Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: A systematic review. International Nursing Review, 62(3), 340–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12194

- Costa, M. B. A. L. D., De Freitas Paúl, M. C. L., Da Costa Azevedo, M. J. T., & Gomes, J. C. R. (2019). Motivações dos cuidadores informais de pessoas com demência e o paradoxo do cuidado. Revista Eletrônica Acervo Saúde, 11(18), e2620. https://doi.org/10.25248/reas.e2620.2019

- DeCaporale-Ryan, L. N., Steffen, A. M., Marwit, S. J., & Meuser, T. M. (2016). Dementia spousal caregivers and past transgressions: Measuring and understanding forgiveness experiences. Journal of Women & Aging, 28(6), 510–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2015.1065143

- Fagerström, C., Elmståhl, S., & Wranker, L. S. (2020). Analyzing the situation of older family caregivers with a focus on health-related quality of life and pain: A cross-sectional cohort study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 18(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01321-3

- Farina, N., Page, T. E., Daley, S., Brown, A., Bowling, A., Basset, T., Livingston, G., Knapp, M., Murray, J., & Banerjee, S. (2017). Factors associated with the quality of life of family carers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 13(5), 572–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2016.12.010

- Galvin, J. (2013). PC-04–03: The importance of family and caregiver in the care and management of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 9(4S_Part_1), 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2013.04.012

- Guermazi, M., Allouch, C., Yahia, M., Huissa, T. B. A., Ghorbel, S., Damak, J., Mrad, M. F., & Elleuch, M. H. (2012). Translation in arabic, adaptation and validation of the sf-36 health survey for use in tunisia. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 55(6), 388–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2012.05.003

- Gull, M., & Rana, S. (2013). Manifestation of forgiveness, subjective well being and quality of life. Journal of Behavioural Sciences, 23(2), 19–36. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Manifestation-of-Forgiveness%2C-Subjective-Well-Being-Gull-Rana/d03acf4b1839878a4d441634919ee739ae52dcc6

- Hazzan, A. A., Dauenhauer, J., Follansbee, P., Hazzan, J. O., Allen, K., & Omobepade, I. (2022). Family caregiver quality of life and the care provided to older people living with dementia: Qualitative analyses of caregiver interviews. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02787-0

- Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(2), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X29657

- Hudson, W. (1993). The walmyr assessment scales scoring manual: Index of family relations (ed.). Walmyr Publishing Company.

- Johnson, P. O., & Fay, L. C. (1950). The Johnson-Neyman technique, its theory and application. Psychometrika, 15(4), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02288864

- Karg, N., Graessel, E., Randzio, O., & Pendergrass, A. (2018). Dementia as a predictor of care-related quality of life in informal caregivers: A cross-sectional study to investigate differences in health-related outcomes between dementia and non-dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0885-1

- Kasuya, R. T., Polgar-Bailey, P., & Takeuchi, R. (2000). Caregiver burden and burnout. A guide for primary care physicians. Postgraduate Medicine, 108(7), 119–123. https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2000.12.1324

- Kazemi, A., Azimian, J., Mafi, M., Allen, K.-A., & Motalebi, S. A. (2021). Caregiver burden and coping strategies in caregivers of older patients with stroke. BMC Psychology, 9(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00556-z

- Kim, H., Chang, M., Rose, K., & Kim, S. (2012). Predictors of caregiver burden in caregivers of individuals with dementia: Predictors of caregiver burden. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(4), 846–855. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05787.x

- Lethin, C., Leino-Kilpi, H., Bleijlevens, M. H., Stephan, A., Martin, M. S., Nilsson, K., Nilsson, C., Zabalegui, A., & Karlsson, S. (2020). Predicting caregiver burden in informal caregivers caring for persons with dementia living at home: A follow-up cohort study. Dementia (London, England), 19(3), 640–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301218782502

- Levi-Belz, Y., & Gilo, T. (2020). Emotional distress among suicide survivors: The moderating role of self-forgiveness. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 341. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00341

- Lindeza, P., Rodrigues, M., Costa, J., Guerreiro, M., & Rosa, M. M. (2020). Impact of dementia on informal care: A systematic review of family caregivers’ perceptions. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, bmjspcare-2020-002242. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002242

- Liu, S., Li, C., Shi, Z., Wang, X., Zhou, Y., Liu, S., Liu, J., Yu, T., & Ji, Y. (2017). Caregiver burden and prevalence of depression, anxiety and sleep disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease caregivers in China. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(9-10), 1291–1300. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13601

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (Dass) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u

- Luiu, A. L., Favez, N., Betrancourt, M., Szilas, N., & Ehrler, F. (2020). Family relationships and alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD, 76(4), 1595–1608. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200125

- Mank, A., Van Maurik, I. S., Rijnhart, J. J. M., Rhodius-Meester, H. F. M., Visser, L. N. C., Lemstra, A. W., Sikkes, S. A. M., Teunissen, C. E., Van Giessen, E. M., Berkhof, J., & Van Der Flier, W. M. (2023). Determinants of informal care time, distress, depression, and quality of life in care partners along the trajectory of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 15(2), e12418. https://doi.org/10.1002/dad2.12418

- Messina, A., Lattanzi, M., Albanese, E., & Fiordelli, M. (2022). Caregivers of people with dementia and mental health during COVID-19: Findings from a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02752-x

- Nemcikova, M., Katreniakova, Z., & Nagyova, I. (2023). Social support, positive caregiving experience, and caregiver burden in informal caregivers of older adults with dementia. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1104250. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1104250

- Pearlin, L. I., Mullan, J. T., Semple, S. J., & Skaff, M. M. (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30(5), 583–594. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/30.5.583

- Pereira, M. G., Abreu, A. R., Rego, D., Ferreira, G., & Lima, S. (2021). Contributors and moderators of quality of life in caregivers of alzheimer’s disease patients. Experimental Aging Research, 47(4), 357–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361073X.2021.1895594

- Pereira, M. G., Brito, L., & Alves, O. (2019). Questionário sociodemográfico. Projeto Investigação-Ação nas Demências, Grupo de Investigação em Saúde & Família. Universidade do Minho.

- Pertl, M. M., Sooknarine-Rajpatty, A., Brennan, S., Robertson, I. H., & Lawlor, B. A. (2019). Caregiver choice and caregiver outcomes: A longitudinal study of Irish spousal dementia caregivers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01801

- Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2003). Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 18(2), 250–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250

- Pope, N., Giger, J., Lee, J., & Ely, G. (2017). Predicting personal self-care in informal caregivers. Social Work in Health Care, 56(9), 822–839. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2017.1344755

- Quinn, C., Nelis, S. M., Martyr, A., Morris, R. G., Victor, C., & Clare, L. (2020). Caregiver influences on ‘living well’ for people with dementia: Findings from the IDEAL study. Aging & Mental Health, 24(9), 1505–1513. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1602590

- Rasmussen, K. R., Stackhouse, M., Boon, S. D., Comstock, K., & Ross, R. (2019). Meta-analytic connections between forgiveness and health: The moderating effects of forgiveness-related distinctions. Psychology & Health, 34(5), 515–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2018.1545906

- Rey, L., & Extremera, N. (2016). Forgiveness and health-related quality of life in older people: Adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies as mediators. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(12), 2944–2954. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315589393

- Rodríguez-Pérez, M., Abreu-Sánchez, A., Rojas-Ocaña, M. J., & del-Pino-Casado, R. (2017). Coping strategies and quality of life in caregivers of dependent elderly relatives. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0634-8

- Roland, K. P., & Chappell, N. L. (2019). Caregiver experiences across three neurodegenerative diseases: Alzheimer’s, parkinson’s, and parkinson’s with dementia. Journal of Aging and Health, 31(2), 256–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264317729980

- Stall, N. M., Kim, S. J., Hardacre, K. A., Shah, P. S., Straus, S. E., Bronskill, S. E., Lix, L. M., Bell, C. M., & Rochon, P. A. (2019). Association of informal caregiver distress with health outcomes of community-dwelling dementia care recipients: A systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(3), 609–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15690

- Steinsheim, G., Saga, S., Olsen, B., Broen, H. K., & Malmedal, W. (2022). Abusive episodes among home-dwelling persons with dementia and their informal caregivers: A cross-sectional Norwegian study. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 852. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03569-4

- Strelan, P. (2018). Justice and Forgiveness in Interpersonal Relationships. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(1), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417734311

- Sutter, M., Perrin, P. B., Chang, Y.-P., Hoyos, G. R., Buraye, J. A., & Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. (2014). Linking family dynamics and the mental health of colombian dementia caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 29(1), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317513505128

- Thompson, L. Y. (2003). The relationship between stress and psoriasis severity: Forgiveness as a moderator. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Kansas]. Proquest. https://www.proquest.com/openview/a18072d47854e485cf5d29ad6c03f9b1/1?cbl=18750&diss=y&pqorigsite=gscholar&parentSessionId=Ir6uot/dBscFFH7aMI6lX7akQNnfiWAJxjzBeooUt74%3D

- Thompson, L. Y., Snyder, C. R., Hoffman, L., Michael, S. T., Rasmussen, H. N., Billings, L. S., Heinze, L., Neufeld, J. E., Shorey, H. S., Roberts, J. C., & Roberts, D. E. (2005). Dispositional forgiveness of self, others, and situations. Journal of Personality, 73(2), 313–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00311

- Välimäki, T. H., Martikainen, J. A., Hongisto, K., Väätäinen, S., Sintonen, H., & Koivisto, A. M. (2016). Impact of Alzheimer’s disease on the family caregiver’s long-term quality of life: Results from an ALSOVA follow-up study. Quality of Life Research, 25(3), 687–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1100-x

- van den Kieboom, R., Snaphaan, L., Mark, R., & Bongers, I. (2020). The trajectory of caregiver burden and risk factors in dementia progression: A systematic review. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD, 77(3), 1107–1115. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200647

- Ware, J. E., Snow, K. K., Kosinski, M., & Gandek, B. (1993). SF-36 health survey manual and interpretation guide (1st ed.). Boston: New England Medical Centre.

- World Health Organization. (2017). Global action plan on the public health response to dementia: 2017–2025. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259615/9789241513487eng.pdf;jsessionid=4DA480FA93471AC53988E52B35F416D8?sequence=1

- Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Scherer, M. (2004). Forgiveness is an emotion-focused coping strategy that can reduce health risks and promote health resilience: Theory, review, and hypotheses. Psychology & Health, 19(3), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/0887044042000196674

- Ye, Y., Ma, D., Yuan, H., Chen, L., Wang, G., Shi, J., Yu, Y., Guo, Y., & Jiang, X. (2019). Moderating effects of forgiveness on relationship between empathy and health-related quality of life in hemodialysis patients: A structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 57(2), 224–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.10.511

- Yu, H., Wang, X., He, R., Liang, R., & Zhou, L. (2015). Measuring the caregiver burden of caring for community-residing people with alzheimer’s disease. PloS One, 10(7), e0132168. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132168

- Zarit, S. H., & Zarit, J. M. (1983). The memory and behavior problems checklist and the burden interview (Technical Report). Pennsylvania State University.