Abstract

Objectives

This scoping review presents an overview of the available research on symptoms, comorbidities, and associated challenges among older adults with ADHD.

Method

The literature study followed Arksey and O’Malley’s five-stage framework. The search was conducted in ProQuest Central, Scopus, PsycInfo, CINAHL, and PubMed. Articles were included if they were peer-reviewed, ethically approved primary studies, written in the English language, concerning ADHD, and including people 60 years of age and older.

Results

The review included 17 articles. Symptoms of ADHD persist throughout life. Older adults with ADHD experience similar core symptoms as younger individuals, but their manifestation and intensity may differ. The most common comorbidity found was mental illness, for example depression and anxiety. ADHD in older adults is linked to several challenges, such as difficulty with relationships and social isolation.

Conclusion

Older adults with ADHD face various symptoms, comorbidities, and challenges that affect their quality of life. Age-related changes can amplify ADHD symptoms and increase the perceived burden of illness. More research is needed to understand the complex relationship between these factors and enable tailored interventions to improve their quality of life and well-being.

Introduction

This scoping review investigates attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in older adults. It addresses three main areas: symptoms commonly observed, frequent comorbidities, and predominant challenges experienced. ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder, that is mainly characterized by inattention, impulsivity, and/or hyperactivity (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022). Although typically associated with younger populations, recent research highlights the prevalence of ADHD in older adults. Still, the research on ADHD in older adults is scarce. As the population ages, it becomes increasingly important to recognize and address the unique needs of older adults with ADHD to improve their quality of life and overall well-being. This review aims to synthesize existing literature to better understand this condition in older adults.

Today, ADHD is diagnosed in the general population more frequently than in the past. Reasons for this might be increased recognition by doctors, increased public awareness, and changes in diagnostic criteria (Xu et al., Citation2018). A worldwide systematic review and meta-analyses (Song et al., Citation2021) covering all WHO regions found a prevalence of 2.6% for persistent adult ADHD (i.e., ADHD that evidently started during childhood) and 6.8% for symptomatic adult ADHD (i.e., that has not necessarily had a childhood onset), translating to 366.33 million adults that could be affected globally.

Although there are some positive traits associated with ADHD, such as energy and cognitive dynamism (Sedgwick et al., Citation2019), there are several associated challenges. ADHD can have a negative impact on social functioning, economic resources, education, and professional life (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022; Küpper et al., Citation2012). Unemployment, unhealthy lifestyle habits, crime, and substance abuse are also more common (Dalsgaard et al., Citation2015; Küpper et al., Citation2012). In addition, ADHD negatively affects executive functioning (i.e., unable to prioritize tasks, poor planning, etc.) and can cause memory problems (Asherson et al., Citation2016). Anxiety and mood disorders are common comorbidities and are often considered secondary symptoms (Kessler et al., Citation2006). ADHD is also associated with increased mortality rates and shorter life expectancy, mainly driven by unnatural causes such as accidents (Dalsgaard et al., Citation2015) and suicides (Giupponi et al., Citation2018).

Older adults are at increased risk for a variety of health issues and concerns, such as cognitive decline, chronic diseases, mental health issues, falls, malnutrition, social isolation, and polypharmacy (Jaul & Barron, Citation2017). Currently, treatment for ADHD in older people is similar to that for younger people (Asherson et al., Citation2016) but due to age-related health problems and the risk of polypharmacy, it can have more serious side effects (Jaul & Barron, Citation2017). A challenge in diagnosing ADHD in older adults is that many of the symptoms of ADHD overlap with symptoms of other mental health conditions and age-related cognitive decline, which can make it difficult to distinguish between them (Goodman et al., Citation2015). In addition, several studies suggest a possible link between ADHD and an increased risk of developing a form of dementia (Becker et al., Citation2021; Callahan et al., Citation2017), highlighting the importance of studying ADHD among older adults. As ADHD negatively affects executive functioning and causes memory problems, both of which are also features of age-related changes (Asherson et al., Citation2016; Jaul & Barron, Citation2017), these symptoms might be even more predominant in older adults with ADHD. Due to several challenges in diagnosing ADHD at an advanced age (Barkley et al., Citation2010; Goodman et al., Citation2015) there might be a high number of undiscovered cases of ADHD in older adults, but that does not diminish the potential impact of the condition.

Given that the proportion of older adults is gradually increasing in societies across the world, ADHD might become a growing topic in the upcoming years. Understanding the challenges faced by older adults with ADHD can lead to better support and interventions, improving their mental and somatic health. This not only enhances their quality of life but also reduces costs for society, making it an important topic to study. The purpose of this scoping review was to present an overview of the available research on symptoms, comorbidities, and associated challenges among older adults with ADHD.

Materials and methods

A scoping review is used to capture key concepts and sources of evidence within a research area that has not been extensively studied and is useful for identifying research gaps (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). This study had some delimitations. There are many undiscovered cases of ADHD. Diagnosing ADHD in older adults involves several challenges (Surman & Goodman, Citation2017). One of them is that the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders) ADHD diagnostic criteria was developed for diagnosing children (Sharma et al., Citation2021), although the most recent edition (DSM-5) developed the diagnostic criteria to better describe typical symptoms in adults. Another is older adult’s ability to recall symptoms during childhood (Sharma et al., Citation2021) and the overlapping features between ADHD and dementia (Prentice et al., Citation2021). This review, however, does not cover this topic. Older adults with ADHD in this scoping review refer to both study participants who have received an official diagnosis and to those who fulfill the diagnostic criteria but are unaware of the diagnosis. Another important topic to investigate is the treatment of ADHD in older adults. This review will not discuss the different treatment options.

This scoping review followed the five stages as described by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005): (1) identifying research questions, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. This scoping review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Stage 1: identifying research questions

As the topic did not seem to have been extensively researched, the initial literature search was broad and concerned everything that was available about older adults and ADHD. To find appropriate articles, two main search blocks were created. The first search block covered the term ADHD and all related synonyms in the English language that were available in Swedish MeSH (National Library of Medicine, Citation2023). The second block contained various terms for ‘older adults’. The reason for using the second block was that the age group was a central factor in this review, and not all databases have an age group limitation, and when they do, the filter does not always function well. The definition of ‘older adults’ varies depending on the source. According to the definition by the United Nations (Dugarova, Citation2017), older adults were defined as people 60 years and older. However, it was only possible to limit the search in the databases to ‘65 years and above’, not ‘60 years and above’. Still, studies with participants aged 60 to 64 years were accepted. The search blocks contained boolean operators and truncation to provide a broader search and to consider gaps in indexing and varying terminology. To enable a better reading of this review, the exact search blocks for each database are presented in Appendix 1. After this broader search, and following the knowledge gaps observed, the following questions guided this scoping review: What is known about the symptoms of older adults with ADHD? Which comorbidities are frequent? What are the predominantly associated challenges?

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

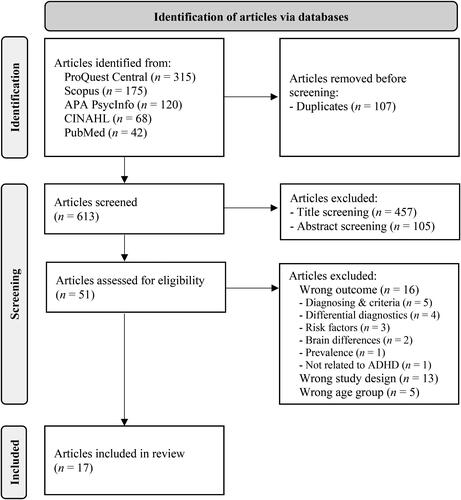

After intensive test searches and additional adjustments in the search terminology, the final search was performed on March 11, 2023, in the following five different databases: ProQuest, Scopus, APA PsycInfo, CINAHL, and PubMed. The broad search blocks remained as described in stage 1 to find as many relevant studies as possible. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were used in the screening process, as presented in .

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Stage 3: study selection

As can be seen in the flow chart (), 720 articles were identified in the five databases when using the two search blocks. All 720 articles were imported to Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., Citation2016), an online tool for managing literature reviews, detecting duplicate articles, and facilitating the inclusion and exclusion of articles. Rayyan also facilitated tracking the various reasons (wrong age group, focus, or study design) for excluding articles. With the help of Rayyan, 107 duplicates were detected, manually screened, and removed. In the title screening, 457 articles were excluded, and 105 in the abstract screening. In this step, most articles were excluded from the study primarily because they were not related to ADHD as they concerned related conditions or other forms of cognitive impairments (such as dementia), or did not address the correct population. Each screening was performed in a row without timely interruption to ensure that all articles were screened with the same state of mind.

During the assessment for eligibility, the three research questions for this scoping review were used to further exclude irrelevant articles. Out of the 51 articles left, 16 were excluded because they were not in line with the research questions (i.e., wrong outcome), 13 were excluded because they were not primary studies (i.e., wrong study design), and five articles were excluded because they concerned the wrong age group, leaving 17 articles for inclusion in this review.

Stage 4: data charting process

The following data items were extracted and presented in Appendix 2: study (author’s name, country, year of publication), study design and population characteristics (research design, sample, participant characteristics), and results (symptoms, comorbidities, challenges).

Stage 5: summarizing results

The results were collated, summarized, and reported, following Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) framework and the PRISMA-ScR checklist (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Results

We identified 17 original studies reporting 203 older adults with ADHD (Brod et al., Citation2012; Das et al., Citation2014; Guldberg-Kjär et al., Citation2013; Guldberg-Kjär & Johansson, Citation2009; Henry & Hill Jones, Citation2011; Michielsen et al., Citation2013, Citation2014, Citation2015, Citation2018; Müller et al., Citation2023; Philipp-Wiegmann et al., Citation2016; Semeijn et al., Citation2013; Citation2015a; Citation2015b; Citation2016; Thorell et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). All studies, apart from two, followed a quantitative or mixed-method approach (Henry & Hill Jones, Citation2011; Michielsen et al., Citation2018). All of the studies were conducted in Western countries, and apart from three (Brod et al., Citation2012, Das et al., Citation2014; Henry & Hill Jones, Citation2011) all were conducted in Europe.

What is known about the symptoms of older adults with ADHD?

General symptoms

Older adults with ADHD may experience similar core symptoms as younger individuals, but the manifestation of these symptoms can differ. In line with the DSM-5-TR criteria, the main symptoms found in older adults by Brod et al. (Citation2012) were inattention (71%), impulsivity (58%), hyperactivity (54%), and disorganization (54%). Michielsen et al. (Citation2018) and Müller et al. (Citation2023) confirmed these core symptoms. Inattention, as a prevalent symptom in older adults, may include forgetfulness, difficulty following instructions, trouble organizing tasks, and procrastination (Brod et al., Citation2012). Hyperactivity may decline with age, but some older adults may still experience restlessness, fidgeting, and difficulty engaging in sedentary activities (Das et al., Citation2014; Müller et al., Citation2023). Impulsivity may also decrease but can still manifest as interrupting others, impatience, or making hasty decisions (Das et al., Citation2014; Müller et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, older adults with ADHD may experience executive dysfunction, leading to difficulties in planning, organizing, and managing time (Thorell et al., Citation2017). However, not all symptoms were solely perceived as negative. Higher levels of hyperactivity/impulsivity, for example, were associated with higher life productivity (Thorell et al., Citation2019). According to Das et al. (Citation2014), greater hyperactivity was also linked to better task-switching abilities in older adults.

Symptom persistence and intensity

Something that became clear in all articles is that symptoms of ADHD continued until old age. Regarding the amount and intensity of symptoms, different results became visible in the studies. According to Semeijn et al. (Citation2016), ADHD symptoms seem to largely remain stable over the lifespan. In addition, Brod et al. (Citation2012) confirmed that symptoms do not get worse with aging. Thorell et al. (Citation2019) concluded that ADHD patients above age 60 are as impaired as younger adults with ADHD in most domains. On the other hand, Das et al. (Citation2014) and Müller et al. (Citation2023) observed that older adults reported fewer and less severe ADHD symptoms compared to middle-aged adults. Especially, impulsivity and hyperactivity seem to decrease across the lifespan (Müller et al., Citation2023). Despite ADHD symptoms persisting throughout life, they seem to impact the study participants more negatively in their younger years (Michielsen et al., Citation2018; Thorell et al., Citation2017).

Memory and cognition

Older adults with ADHD performed at a significantly lower level compared to healthy controls in working memory, inhibition, and processing speed compared to healthy controls (Semeijn et al., Citation2015b; Thorell et al., Citation2017). According to Guldberg-Kjär et al. (Citation2013) and Guldberg-Kjär and Johansson (Citation2009) perceived memory problems were found to be related to ADHD. In Brod et al. (Citation2012), 21% of older adults expressed concern that ADHD symptoms were cognitive problems/dementia due to aging. Furthermore, Das et al. (Citation2014) and Semeijn et al. (Citation2015b) found that the relationship between ADHD symptoms and cognitive performance changes with age, and the effect of ADHD symptoms on cognitive performance is weaker and mostly indirect in older adults due to the strong association between depression symptoms and cognition. Lower cognitive performance in older adults with ADHD seems to be limited to attention and working memory (Semeijn et al., Citation2015b). Despite strong evidence of memory problems, Thorell et al. (Citation2017) found that 20% of older adults with ADHD show no clear neuropsychological deficits. Guldberg-Kjär et al. (Citation2013) argue that age-related cognitive changes may have a greater impact on individuals with a history of ADHD compared to those without.

Which comorbidities are frequent?

Psychiatric comorbidities

Mental health comorbidities are common among older adults with ADHD (Brod et al., Citation2012; Michielsen et al., Citation2013, Citation2014, Citation2015; Müller et al., Citation2023; Philipp-Wiegmann et al., Citation2016; Semeijn et al., Citation2013, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Thorell et al., Citation2019). For example, in the study by Brod et al. (Citation2012) 54% of the study subjects suffered from depression, 42% from anxiety, and 8% had bipolar disorder. Depression and anxiety symptoms are also significantly more common and clinically relevant in older adults with ADHD compared to those without ADHD (Michielsen et al., Citation2013). Das et al. (Citation2014) observed that depression symptoms were less common in older adults with ADHD, but that they had a stronger impact on cognitive performance. According to Michielsen et al. (Citation2014), low self-esteem and mastery, which were related to ADHD in older adults, also showed a clear connection to depressive symptoms. Several of the discovered ADHD symptoms and associated challenges turned out to be insignificant when adjusting for depressive symptoms (Semeijn et al., Citation2015b). For example, the association between higher ADHD symptom levels and lower income (Michielsen et al., Citation2015). Learning disorders, oppositional behavior, eating, and post-traumatic stress disorders were other observed conditions to be more prevalent among older adults with ADHD (Philipp-Wiegmann et al., Citation2016).

Substance abuse

Another frequently mentioned comorbidity is substance abuse, for example, alcohol, nicotine, and drugs (Brod et al., Citation2012; Philipp-Wiegmann et al., Citation2016). Brod et al. (Citation2012) found that 25% of their study subjects had this comorbidity. On the other hand, Semeijn et al. (Citation2013) could not observe an association between symptoms of ADHD and lifestyle variables such as drinking and smoking.

Somatic comorbidities

Brod et al. (Citation2012) stated that all participants in their study were physically independent. None of the other studies mentioned whether any participants resided in any type of facility or were physically dependent. This is consistent with Semeijn et al. (Citation2013), who did not discover any significant relationship between ADHD diagnosis and physical health or lifestyle factors. However, they identified a significant positive correlation between ADHD symptoms and cardiovascular disease (CVD) in older adults but no association with hypertension, body mass index (BMI), or waist circumference.

What are the predominant associated challenges?

Education, professional life, and finances

In Brod et al. (Citation2012) 92% of the study participants held a college or graduate degree, and 77% showed an above median household income. Still, 75% of the study participants reported a negative impact on education, and 83% reported a negative impact on professional life. Other studies also confirmed difficulties in school and professional life, such as maintaining employment and achieving career goals (Henry & Hill Jones, Citation2011; Michielsen et al., Citation2015). Older adults with ADHD have changed professions more frequently than same-aged individuals without ADHD (Guldberg-Kjär & Johansson, Citation2009; Philipp-Wiegmann et al., Citation2016). In addition, a negative impact on money management was also observed by Philipp-Wiegmann et al. (Citation2016) and Brod et al. (Citation2012).

Social life and relationships

Other challenges observed by Brod et al. (Citation2012) were negative impact on relationships (58%), and social life (24%). These challenges were similarly reported in studies by Philipp-Wiegmann et al. (Citation2016), Thorell et al. (Citation2019), and Henry and Hill Jones (Citation2011). In Brod et al. (Citation2012), 71% of the study participants reported alienation from friends, family, and co-workers. Similar numbers were also observed by Henry and Hill Jones (Citation2011) who stated that 77% of the study participants reported peer rejection, feeling alone or isolated, difficulties with relationships with family members, and feeling different or reacting differently than other people. Feeling misunderstood was also one of the main themes found in Michielsen et al. (Citation2018). ADHD in older adults was associated with social inadequacy (Michielsen et al., Citation2014), a higher risk of being divorced/never married, fewer family members in the social network, a lower number of family members seen weekly, and higher emotional loneliness (Michielsen et al., Citation2015). Despite confirming ‘stormy’ relationships, higher divorce rates could not be observed by Henry & Hill (2011). In addition, Semeijn et al. (Citation2015a) found that serious ADHD-related conflicts persist from childhood into old age, affecting relationships. Likely due to impulsivity, older adults with ADHD also often perceive themselves as advocates for the underdog (33%) who do not mind being a loner (Henry & Hill Jones, Citation2011). A higher level of ADHD symptoms was also associated with more emotional support given (Michielsen et al., Citation2015). In addition, difficulty saying ‘no’ or saying ‘yes’ too fast may lead to overstepping boundaries and increasing the risk of burnout (Michielsen et al., Citation2018). Consistent with this finding, Guldberg-Kjär et al. (Citation2013) discovered that older adults with ADHD may underestimate their impairments, meaning they might not fully recognize their limitations. Supportive spouses have been found to decrease negative impacts in older adults with ADHD (Brod et al., Citation2012).

Psychological health and quality of life

ADHD in older adults also negatively influenced their psychological health, reducing the quality of life of the study participants (Brod et al., Citation2012; Thorell et al., Citation2019). Older adults with ADHD report poorer self-perceived health (Guldberg-Kjär et al., Citation2013; Guldberg-Kjär & Johansson, Citation2009; Semeijn et al., Citation2013; Thorell et al., Citation2019). Connected to this, Michielsen et al. (Citation2014, Citation2018) found that ADHD in older adults was significantly associated with low self-esteem, low self-efficacy, and low mastery. Additionally, older adults with ADHD may experience poor quality of life in domains such as life productivity, life outlook, relationships, and psychological health but show at the same time better psychological health than younger adults with ADHD (Thorell et al., Citation2019).

Life management

Several studies (Michielsen et al., Citation2015, Citation2018; Philipp-Wiegmann et al., Citation2016; Thorell et al., Citation2017) found that ADHD in older adults also involved difficulties in organizing and managing daily tasks, which could be caused by working memory deficits (Thorell et al., Citation2017). This challenge may lead to lower self-esteem, feelings of inadequacy, and a sense of failure (Michielsen et al., Citation2015). Likewise, Brod et al. (Citation2012) found organizing difficulties to be very common.

Positive aspects

Despite the challenges that may follow ADHD, Brod et al. (Citation2012) found that 46% of the participants perceived some positive aspects, such as higher creativity than people without ADHD, enthusiasm, awareness of the multiplicity of things, and hyper-focus/multitasking when interested. Developing coping strategies because of ADHD may lead to increased resilience in later life (Michielsen et al., Citation2018). Also, in Henry and Hill Jones (Citation2011) study, participants reported resilience and creativity in their careers which helped to compensate for the challenges. In addition, older adults with ADHD showed greater participation in recreational activities than study participants without the disorder. Being active in old age and being able to act spontaneously was also seen as positive (Michielsen et al., Citation2018).

Discussion

This study aimed to provide an overview of the available research on symptoms, comorbidities, and challenges older adults with ADHD face. ADHD symptoms remain throughout life. Older adults with ADHD have similar core symptoms as younger individuals, but symptom manifestation and intensity may differ. Besides substance abuse, mental health comorbidities were very common among the study participants, potentially exacerbating ADHD symptoms. One of the main associated challenges found was difficulties with social relationships.

As shown by the studies included in this scoping review, the prevalence of ADHD in older adults appears to be lower than the prevalence in children or middle-aged adults (e.g., Das et al., Citation2014; Müller et al., Citation2023). There might be several explanations for this. Many or most older adults have not been screened for ADHD because, when they reached adulthood, ADHD was not a known disorder or was not considered to be a disorder that could affect adults (Epstein & Loren, Citation2013). Symptoms such as impulsivity were instead attributed to a person’s personality or a personality disorder (Barkley et al., Citation2010). Goodman et al. (Citation2015) found that symptoms can change over the lifespan and become a less obvious sign of ADHD. For example, with age, hyperactivity can change from physical hyperactivity to mental hyperactivity (Pierre et al., Citation2019) which may be less observable among older adults. Lack of concentration and memory problems in older adults could be symptoms of such mental hyperactivity, but they could also be interpreted as symptoms of other conditions, such as dementia (Goodman et al., Citation2015). Moreover, as all study subjects most likely received their diagnosis during adulthood (e.g., Brod et al., Citation2012; Henry & Hill Jones, Citation2011), it could be argued that their symptoms were less severe than if someone had received their diagnosis during childhood. Also, accepting that ADHD symptoms persist throughout the lifespan is quite recent (Epstein & Loren, Citation2013). Additionally, inattention symptoms as part of ADHD were first added to the diagnostic manual in 1980 (Goodman et al., Citation2015). Therefore, many of today’s older adults did not have the opportunity to receive a diagnosis.

The symptom manifestation of ADHD in older adults may be influenced by normal aging processes and life stage changes (Michielsen et al., Citation2018). To better understand this influence, applying a life course perspective could be beneficial (Elder et al., Citation2003) as it acknowledges the influence of individual life trajectories. For instance, an individual may have grown up in a stressful environment, which might have contributed to the development or exacerbation of their ADHD symptoms. During adulthood, the development of coping strategies or seeking treatment may have led to a reduction in symptoms. However, upon retirement, the loss of regular routines, structure, and social interactions could potentially lead to an increased visibility of ADHD symptoms. In addition, the age-related cognitive decline (Harada et al., Citation2013) may also exacerbate ADHD symptoms related to memory, attention, and decision-making. Understanding the variations in ADHD symptoms could therefore help in developing tailored interventions and support systems that account for these unique experiences and challenges.

As became clear in several studies included in this scoping review (e.g., Das et al., Citation2014; Michielsen et al., Citation2018; Thorell et al., Citation2017), many older adults perceived their symptoms as less severe than when they were younger or than the symptoms are. In addition, Müller et al. (Citation2023) observed a slightly lower burden in older adults with ADHD compared to middle-aged adults with ADHD, despite a similar level of symptoms. On the one hand, this could mean that the symptoms are less, but on the other hand, it could also mean that during their lifespan, older adults have acquired good coping mechanisms to handle challenges such as the ones caused by ADHD (Michielsen et al., Citation2018) or reached an acceptance of the way they are (Carstensen, Citation2006). Henry and Hill Jones (Citation2011) observed that receiving a diagnosis and treatment also helped with self-acceptance and appreciation of potential strengths. Older adults may have adjusted their expectations and developed resilience through accumulated life experiences, which could contribute to a lower perceived burden of ADHD compared to middle-aged adults with ADHD. This feeling of acceptance or satisfaction could also lead to not searching for medical help or even requesting an ADHD screening. Also, mental challenges might be perceived as less stigmatizing for younger generations, and/or they have a higher awareness of this topic and are hence also more likely to search for and accept psychological or psychiatric help (e.g., Adams et al., Citation2021; Conner et al., Citation2010; Wuthrich & Frei, Citation2015).

The two main comorbidities associated with ADHD found in this review were mental health and substance abuse disorders, potentially leading to an additional burden for older adults with ADHD (Michielsen et al., Citation2013). Several other studies showed, in addition, a clear relationship or co-existence of both disorders (Grant et al., Citation2004; Kelly & Daley, Citation2013) meaning that all three disorders are somehow linked. One explanation for this connection could be that people with, for example, depression or ADHD try to self-medicate by using alcohol or other drugs, leading to severe health problems (Ruiz, Citation2010). Depression and anxiety among older adults are very frequent but are often neither diagnosed nor treated properly because it is often seen as an integral part of aging by both medical practitioners and patients (Frost et al., Citation2019). However, considering the strong relationship, it might be difficult to relate certain symptoms and challenges to either ADHD or depression.

One of the main challenges related to ADHD was difficulties in and with social relationships. Challenges related to ADHD, such as impulsivity and social inadequacy, can lead to challenges in forming and maintaining relationships. These challenges may result in a higher risk of being divorced or never married, fewer family members in the social network, and increased emotional loneliness. As loneliness and social isolation are common among older adults (Donovan & Blazer, Citation2020), ADHD-related conflicts could exacerbate these feelings. Michielsen et al. (Citation2015) found that the divorce rates were higher among people with ADHD, whereas Henry and Hill Jones (Citation2011) showed that, while relationships such as marriages were turbulent, the divorce rate was not different from people without ADHD. A reason for this might be that it was less common to divorce in the past. The importance of supportive spouses who helped organize daily business was also made clear in several studies not part of this scoping review (Buchalter & Lantz, Citation2003; Wetzel & Burke, Citation2008). The dependency on the spouse can make a relationship more like a parentship and not like a partnership, and the death of the spouse can have a huge impact, not just emotionally but because of the organizational responsibilities that suddenly need to be taken care of, according to Wetzel and Burke (Citation2008). Although objective symptoms are lower compared to younger individuals with ADHD, older adults may experience a higher burden of illness due to the challenges associated with aging (Brod et al., Citation2012).

Still, despite all the symptoms, comorbidities, and challenges, some of the studies also highlighted certain positive aspects. Sedgwick et al. (Citation2019) conducted a small-scale qualitative study and found, for example, cognitive dynamism, energy, divergent thinking, hyper-focus, nonconformist, adventurousness, self-acceptance, and sublimation as positive behavioral traits specifically linked to ADHD. Several of these behavioral traits were also noted in this review. For example, it seemed very common for older adults with ADHD to have an active and ‘busy’ life that kept them physically and mentally active.

Strengths and limitations

The search strategy was comprehensive and the help of subject matter experts, and synonyms found in SwedishMesh were used to reduce the potential risk of bias and to present the results in a transparent and traceable manner (Tricco et al., Citation2018), thus establishing validity for this review. The reliability and credibility of a study depend on the documentation of the search process. In this study, the best effort was made to ensure transparency in the screening and study selection processes. Using Rayyan for screening and tracking reasons for the exclusion of articles might help others replicate the search and increase the transferability of the findings. Following Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) scoping review framework and PRISMA-ScR guidelines helped increase the transparency of this review. Clear inclusion and exclusion criteria were then utilized to screen articles effectively. However, limiting this review to peer-reviewed articles that went through ethical approval might be a drawback, as it potentially overlooks important aspects or results in a biased or narrow perspective of the studied topic. Also, due to the low availability of studies, it was not possible to present separate findings based on more narrow age groups or levels of ability among older adults with ADHD, such as intellectual disabilities or other learning difficulties. It was not always easy to distinguish between symptoms, comorbidities, and challenges because many of the aspects overlapped and influenced each other. In these cases, an attempt was made to select the most appropriate category. Despite the heterogeneity of the included studies, not many researchers seem to have studied this topic; eight of the 17 included articles were from a group of researchers Michielsen and Semeijn belonged to, two articles were from Guldberg-Kjär et al., and two from Thorell et al. As each group of researchers is using the same study participants in all of their studies, the true total sample size of older adults with ADHD included in this review is very low, covering only five countries (USA, Australia, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Germany). This is a strong limitation of this review, affects its generalizability, and emphasizes the need for further research. Still, acknowledging this research area in a scoping review is an attempt to bring attention to this highly important subject, with hopes of adding to the international literature.

Conclusions

ADHD in older adults is associated with various symptoms, comorbidities, and challenges that can significantly impact their quality of life. While the prevalence of ADHD seems to decrease with age, possibly due to underdiagnosis and improved coping mechanisms, symptoms persist throughout life. The most frequent comorbidity found was mental illness, such as depression and anxiety, and a common challenge was difficulties with relationships and social isolation. Clinically, differentiating between ADHD symptoms and age-related cognitive decline or mental health comorbidities is essential, alongside addressing, for example, polypharmacy. More research is needed to better understand ADHD in older adults and its associated challenges. For example, investigating interactions between consequences following ADHD and challenges in older ages, such as inattention and adherence to medication, learning more about similarities between ADHD and early stages of a dementia diagnosis, or possible interventions to increase social relations in this group.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (37.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, C., Gringart, E., Strobel, N. A., & Masterman, P. W. (2021). Help-seeking for mental health problems among older adults with chronic disease: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(4), 426–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1952850

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision DSM-5-TR. (5th ed.)

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Asherson, P., Buitelaar, J., Faraone, S. V., & Rohde, L. A. (2016). Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: Key conceptual issues. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 3(6), 568–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30032-3

- Barkley, R. A., Murphy, K. R., & Fischer, M. (2010). ADHD in Adults: What the Science Says. Guilford Press.

- Becker, S. J., Sharma, M., & Callahan, B. L. (2021). ADHD and neurodegenerative disease risk: A critical examination of the evidence. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 13, 826213. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.826213

- Brod, M., Schmitt, E. M., Goodwin, M., Hodgkins, P., & Niebler, G. (2012). ADHD burden of illness in older adults: A life course perspective. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 21(5), 795–799. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9981-9

- Buchalter, E. N., & Lantz, M. S. (2003). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in late life. Clinical Geriatrics, 11(8), 34–36.

- Callahan, B. L., Bierstone, D., Stuss, D. T., & Black, S. E. (2017). Adult ADHD: Risk factor for dementia or phenotypic mimic? Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 9, 260. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2017.00260

- Carstensen, L. L. (2006). The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science , 312(5782), 1913–1915. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127488

- Conner, K. O., Copeland, V. C., Grote, N. K., Koeske, G. F., Rosen, D. G., Reynolds, C. F., & Brown, C. (2010). Mental health treatment seeking among older adults with depression: The impact of stigma and race. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(6), 531–543. https://doi.org/10.1097/jgp.0b013e3181cc0366

- Dalsgaard, S., Østergaard, S. D., Leckman, J. F., Mortensen, P. B., & Pedersen, M. G. (2015). Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A nationwide cohort study. Lancet , 385(9983), 2190–2196. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61684-6

- Das, D., Cherbuin, N., Easteal, S., & Anstey, K. J. (2014). Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and cognitive abilities in the late-life cohort of the PATH through life study. PLOS One, 9(1), e86552. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086552

- Donovan, N. J., & Blazer, D. G. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Review and commentary of a National Academies report. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(12), 1233–1244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.08.005

- Dugarova, E. (2017). Ageing, older persons and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: United Nations Development Programme. https://www.undp.org/publications/ageing-older-persons-and-2030-agenda-sustainabledevelopment

- Elder, G. H., Johnson, M. K., & Crosnoe, R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan, M. J. (Eds), Handbook of the Life Course. (pp. 3–19) Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-306-48247-2_1

- Epstein, J. N., & Loren, R. E. A. (2013). Changes in the definition of ADHD in DSM-5: Subtle but important. Neuropsychiatry, 3(5), 455–458. https://doi.org/10.2217/npy.13.59

- Frost, R., Beattie, A., Bhanu, C., Walters, K., & Ben-Shlomo, Y. (2019). Management of depression and referral of older people to psychological therapies: A systematic review of qualitative studies. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 69(680), e171–e181. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp19X701297

- Giupponi, G., Giordano, G., Maniscalco, I., Erbuto, D., Berardelli, I., Conca, A., Lester, D., Girardi, P., & Pompili, M. (2018). Suicide risk in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatria Danubina, 30(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.24869/psyd.2018.2

- Goodman, D. W., Mitchell, S., Rhodewalt, L., & Surman, C. B. H. (2015). Clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in older adults: A review of the evidence and its implications for clinical care. Drugs & Aging, 33(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-015-0327-0

- Grant, B. F., Stinson, F. S., Dawson, D. V., Chou, S. P., Dufour, M. C., Compton, W. M., Pickering, R. P., & Kaplan, K. B. (2004). Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(8), 807–816. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807

- Guldberg-Kjär, T., & Johansson, B. (2009). Old people reporting childhood AD/HD symptoms: Retrospectively self-rated AD/HD symptoms in a population-based Swedish sample aged 65–80. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 63(5), 375–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480902818238

- Guldberg-Kjär, T., Sehlin, S., & Johansson, B. (2013). ADHD symptoms across the lifespan in a population-based Swedish sample aged 65 to 80. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(4), 667–675. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610212002050

- Harada, C. N., Natelson Love, M. C., & Triebel, K. L. (2013). Normal cognitive aging. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 29(4), 737–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2013.07.002

- Henry, E., & Hill Jones, S. (2011). Experiences of older adult women diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Women & Aging, 23(3), 246–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2011.589285

- Jaul, E., & Barron, J. (2017). Age-related diseases and clinical and public health implications for the 85 years old and over population. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 335. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00335

- Kelly, T. J., & Daley, D. C. (2013). Integrated treatment of substance use and psychiatric disorders. Social Work in Public Health, 28(3–4), 388–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2013.774673

- Kessler, R. C., Adler, L., Barkley, R., Biederman, J., Conners, C. K., Demler, O., Faraone, S. V., Greenhill, L. L., Howes, M. J., Secnik, K., Spencer, T., Ustun, T. B., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2006). The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(4), 716–723. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.716

- Küpper, T., Haavik, J., Drexler, H., Ramos-Quiroga, J. A., Wermelskirchen, D., Prutz, C., & Schauble, B. (2012). The negative impact of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on occupational health in adults and adolescents. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 85(8), 837–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-012-0794-0

- Michielsen, M., Comijs, H. C., Aartsen, M. J., Semeijn, E. J., Beekman, A. T. F., Deeg, D. J. H., & Kooij, J. J. S. (2015). The relationships between ADHD and social functioning and participation in older adults in a population-based study. Journal of Attention Disorders, 19(5), 368–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054713515748

- Michielsen, M., Comijs, H. C., Semeijn, E., Beekman, A. T., Deeg, D. J. H., & Kooij, J. J. S. (2013). The comorbidity of anxiety and depressive symptoms in older adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A longitudinal study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 148(2–3), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.063

- Michielsen, M., Comijs, H. C., Semeijn, E., Beekman, A. T., Deeg, D. J. H., & Kooij, J. J. S. (2014). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and personality characteristics in older adults in the general Dutch population. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(12), 1623–1632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2014.02.005

- Michielsen, M., De Kruif, J. T. C., Comijs, H. C., Van Mierlo, S., Semeijn, E., Beekman, A. T., Deeg, D. J. H., & Kooij, J. J. S. (2018). The burden of ADHD in older adults: A qualitative study. Journal of Attention Disorders, 22(6), 591–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054715610001

- Müller, M., Turner, D., Barra, S., Rösler, M., & Retz, W. (2023). ADHD and associated psychopathology in older adults in a German community sample. Journal of Neural Transmission, 130(3), 313–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-022-02584-4

- National Library of Medicine. (2023). Attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity. Medical subject headings (MeSH). https://mesh.kib.ki.se/term/D001289/attention-deficit-disorder-with-hyperactivity.

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Philipp-Wiegmann, F., Retz-Junginger, P., Retz, W., & Rösler, M. (2016). The intraindividual impact of ADHD on the transition of adulthood to old age. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 266(4), 367–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-015-0644-7

- Pierre, M., Cogez, J., Lebain, P., Loisel, N., Lalevée, C., Bonnet, A. L., De La Sayette, V., & Viader, F. (2019). Detection of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with cognitive complaint: Experience of a French memory center. Revue Neurologique, 175(6), 358–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2018.09.021

- Prentice, J. L., Schaeffer, M. J., Wall, A. K., & Callahan, B. L. (2021). A systematic review and comparison of neurocognitive features of late-life attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and dementia with lewy bodies. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 34(5), 466–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988720944251

- Ruiz, M. E. (2010). Risks of self-medication practices. Current Drug Safety, 5(4), 315–323. https://doi.org/10.2174/157488610792245966

- Sedgwick, J., Merwood, A., & Asherson, P. (2019). The positive aspects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A qualitative investigation of successful adults with ADHD. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 11(3), 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-018-0277-6

- Semeijn, E., Comijs, H. C., De Vet, H. C., Kooij, J. J. S., Michielsen, M., Beekman, A. T., & Deeg, D. J. H. (2016). Lifetime stability of ADHD symptoms in older adults. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 8(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-015-0178-x

- Semeijn, E., Comijs, H. C., Kooij, J. J. S., Michielsen, M., Beekman, A. T., & Deeg, D. J. H. (2015a). The role of adverse life events on depression in older adults with ADHD. Journal of Affective Disorders, 174, 574–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.048

- Semeijn, E., Kooij, J. J. S., Comijs, H. C., Michielsen, M., Deeg, D. J. H., & Beekman, A. T. (2013). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, physical health, and lifestyle in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(6), 882–887. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12261

- Semeijn, E., Korten, N., Comijs, H. C., Michielsen, M., Deeg, D. J. H., Beekman, A. T., & Kooij, J. J. S. (2015b). No lower cognitive functioning in older adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(9), 1467–1476. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610215000010

- Sharma, M. J., Lavoie, S., & Callahan, B. L. (2021). A call for research on the validity of the age-of-onset criterion application in older adults being evaluated for ADHD: A review of the literature in clinical and cognitive psychology. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(7), 669–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.10.016

- Song, P., Zha, M., Yang, Q., Zhang, Y., Li, X., & Rudan, I. (2021). The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Global Health, 11, 04009. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.11.04009

- Surman, C. B., & Goodman, D. W. (2017). Is ADHD a valid diagnosis in older adults? Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 9(3), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-017-0217-x

- Thorell, L. B., Holst, Y., Chistiansen, H., Kooij, J. J. S., Bijlenga, D., & Sjöwall, D. (2017). Neuropsychological deficits in adults age 60 and above with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 45, 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.06.005

- Thorell, L. B., Holst, Y., & Sjöwall, D. (2019). Quality of life in older adults with ADHD: Links to ADHD symptom levels and executive functioning deficits. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 73(7), 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2019.1646804

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Wetzel, M. W., & Burke, W. J. (2008). Addressing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in later adulthood. Clinical Geriatrics, 16(11), 33–39.

- Wuthrich, V. M., & Frei, J. (2015). Barriers to treatment for older adults seeking psychological therapy. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(7), 1227–1236. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610215000241

- Xu, G., Strathearn, L., Liu, B., Yang, B., & Bao, W. (2018). Twenty-year trends in diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among US children and adolescents, 1997–2016. JAMA Network Open, 1(4), e181471. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1471