Abstract

Objectives

In view of the accumulated stress associated with the combination of intergenerational trauma and minority stress, we aimed to examine whether offspring of Holocaust survivors (OHS) reported stronger evil-related threats compared to non-OHS individuals and whether OHS gay men experienced stronger threats. We also examined whether sexual orientation moderated the hypothesized indirect effect of Holocaust background on mental health through evil-related threats.

Method

Participants were 346 middle-aged and older Israeli men (mean age = 60.56, SD = 8.42, range 50–86). Among them, 173 identified as gay men, and 81 identified as OHS. Participants completed measures of evil-related threats, depression, and life satisfaction.

Results

Analysis of covariance revealed that OHS men reported stronger evil-related threats compared to non-OHS men. Yet, an interaction between Holocaust background and sexual orientation indicated that OHS gay men reported stronger evil-related threats compared to non-OHS gay men, while no such difference existed among heterosexual counterparts. Conditional indirect effect analysis showed a significant indirect effect, in which Holocaust background related to higher depressive symptoms and lower life satisfaction through evil-related threats among gay men, but not among heterosexual men.

Conclusion

This study sheds light on the particular experience of evil-related threats, focusing on older OHS gay men and the mental health vulnerability associated with it. In applied contexts, this might help identify a sexual minority group that is particularly sensitive to adverse mental health and offer it supporting interventions.

Introduction

Intergenerational transmission of trauma refers to the persistence of traumatic effects across successive generations, manifesting in both physiological and psychosocial aspects of subsequent cohorts. Various psychodynamic, sociological, and epidemiological theories have been proposed to elucidate how exposure of individuals to highly adverse events often lead subsequent generations to contend with their parents’ post-traumatic conditions (Lehrner & Yehuda, Citation2018).

This transmission has been investigated in the context of offspring of Holocaust survivors (OHS), with research revealing little disparities in mental health between OHS and control cohorts (Sagi-Schwartz et al., Citation2008; Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2003). Nevertheless, further research on OHS indicated intergenerational transmission of the parental trauma under adverse situations as well as in particular relation to over-sensitized familial patterns (Shrira, Citation2016). Such intergenerational effects were explained by various mechanisms such as undue overprotection, enmeshed relationships, and poor communication among survivors and their children relative to comparisons (Palgi et al., Citation2015; Wiseman & Barber, Citation2008).

Notably, the traumatic effects among OHS have been revealed when this generation reached middle and older age. Addressing this issue, Shrira (Citation2023) has delineated an interdisciplinary, integrative model with intricate pathways linking parental Holocaust exposure to the aging process of descendants. These pathways encompass psychological, behavioral, and biological factors, which are most pronounced under adverse circumstances. An intriguing theme in this context, yet scarcely investigated, is the potentially heightened susceptibility of OHS to evil-related self-perceived threats. Furthermore, the potential interplay between the Holocaust background of OHS and their possible affiliation with a sexual minority may accentuate perceptions of evil-related threats. Hence, the present study endeavors to examine whether OHS exhibit heightened propensity to envisage scenarios involving evil in comparison to their non-OHS counterparts, to ascertain whether this propensity is distinctive among OHS identifying as gay men, and to explore how such propensity is associated with mental health.

The concept of evil, characterized by malevolent deeds that deliberately inflict suffering or death, has been a persistent concern throughout human history (Nys & de Wijze, Citation2019). The specter of human evil, whether encountered within the ordinary social fabric of daily existence or in extraordinary realms of atrocities as witnessed in times of war and terrorism, remains an ever-present peril. The harrowing ordeal of World War II laid bare an extensive manifestation of human evil, leaving those traumatized by extreme malevolence to grapple with a sense of ‘afterwardsness.’ This psychological state compels them to restore a semblance of order and control by vigilantly monitoring present-life threats reminiscent of the core trauma (Lazar, Citation2016). Such a vigilant stance, stemming from past trauma (Janoff-Bulman, Citation1989), may linger into subsequent generations, fostered by family dynamics that complicate processes of separation and individuation, as revealed among OHS (Brom et al., Citation2001; Juni, Citation2016; Kellermann, Citation2001; Letzter-Pouw et al., Citation2014).

The notion of perceived threats of evil was drawn from the conceptual model on the pursuit of happiness in a hostile world (Shmotkin, Citation2005), which elucidates strategies that individuals employ to safeguard their well-being when confronted with real or potential adversities. Evil-related threats appeared as a distinct theme within the general construct of hostile-world scenario, defined as an image of actual or potential self-perceived threats to one’s life, or more broadly, to one’s physical or mental integrity. Reflecting the imperative of sustaining mental health in a hostile world, this construct appears increasingly consequential with progression to older age (Shmotkin, Citation2011). Thus, the hostile-world scenario, including evil-related threats alongside other themes of harsh adversities that may disrupt human lives, indeed reflects vulnerability and distress; yet, it serves to scan for imminent dangers or else detect already present hardships (Lifshitz et al., Citation2020; Shmotkin et al., Citation2016). Within this conceptual context, the present study examines the particular role of evil-related threats. Following a separate work on Holocaust survivors (Shmotkin & Bluvstein, Citation2024) and leaning on the aforementioned literature on OHS, we expected that OHS, compared to non-OHS, individuals would report stronger evil-related threats.

Accentuated perceptions of evil-related threats may be highly relevant in contexts of sexual minorities as well as older age. Meyer’s theory of minority stress (Frost & Meyer, Citation2023) emphasizes that being exposed to social malevolence, such as gay bashing or victimization by family and peers due to one’s sexual orientation, can significantly contribute to poor mental health. Similarly, in terms of perceiving scenarios of a hostile world, findings showed that sexual minority individuals, compared to heterosexual counterparts, tended to experience greater fear regarding potential victimization (through crime or discrimination) as well as worries about a lack of social and family support, poor health conditions, disrupted relationships, and challenges related to aging (Shenkman & Shmotkin, Citation2013; Shenkman et al., Citation2020).

However, the extent to which older sexual minorities perceive threats of evil remains unexplored. Furthermore, when considering the aging process within the gay men community, it is essential to address evil-related threats. Thus, older gay individuals, who came of age before significant events like the Stonewall riots and the removal of homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, often faced substantial victimization and pervasive stigma. This societal stance frequently led older sexual minority individuals to conceal their sexual orientation (Kimmel, Citation2014) and posed a burden on their mental health (Haarmann et al., Citation2024). These conditions possibly affected perceptions of evil in one’s social world.

The intersection between the Holocaust background and one’s sexual orientation should also be considered. Previous research indicated that among older gay men, the combination of early familial vulnerability stemming from a Holocaust background, coupled with belonging to a sexual minority group, could engender greater susceptibility to perceiving a hostile world through interpersonal vulnerability (Shenkman, Shrira, et al., Citation2018). Building upon these earlier findings, we further expected that the gap between OHS and non-OHS in perceptions of evil-related threats would be larger among gay, compared to heterosexual, men.

Furthermore, although earlier studies suggested that OHS individuals generally did not exhibit a consistent association with adverse mental health outcomes (Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2003), it was indicated that vulnerabilities in mental health among OHS individuals might become more apparent in the presence of additional stressors, such as the Iranian nuclear threat (Shrira, Citation2015), the Russo-Ukrainian conflict (Greenblatt-Kimron et al., Citation2023), or physical ailments (Baider et al., Citation2006). Consequently, it has been recommended to examine the potential vulnerability of OHS individuals by more interactive, moderating or mediating, factors (Danieli et al., Citation2017).

In this line, a previous study indeed demonstrated that there were no discernible differences in mental health between OHS and non-OHS gay men, and yet, being an OHS gay man was associated with heightened perceptions of interpersonal vulnerability. This, in turn, was linked to less favorable mental health outcomes such as more depressive symptomatology and less life satisfaction (Shenkman, Shrira, et al., Citation2018). Based on this indirect effect, the authors proposed that the amalgamation of being an OHS individual with the stressors linked to being a sexual minority could be conducive to mental health vulnerability. Continuing this line of research, we sought to examine a conditional indirect effect model whereby we anticipated that among gay men, more than among heterosexual counterparts, there would be an indirect effect of having a Holocaust background on mental health through evil-related threats.

The Israeli context

In Israel, it is crucial to recognize the significant challenges faced by older gay men as they grew up in a society where their sexual identity was considered criminal and pathological until 1988 when Israel’s Knesset repealed the law criminalizing homosexuality (Shokeid, Citation2003). Moreover, Israel’s patriarchal culture, strengthened by compulsory military service and adherence to biblical norms disapproving of homosexuality, reinforced traditional masculine stereotypes (Kaplan, Citation2008). This environment may have led to internalized homonegativity, adversely affecting the mental health of gay men (Wen & Zheng, Citation2019).

Additionally, limited access to marriage, adoption, and surrogacy services (until recently) for gay men (Shenkman, Segal-Engelchin, et al. Citation2022) may perpetuate institutional discrimination and harm the mental health of sexual minorities (Hatzenbuehler et al., Citation2010). Moreover, for older individuals, Israeli society relies heavily on support from spouses and children for social and healthcare assistance (Berg-Warman et al., Citation2018), yet the abovementioned discrimination in access to couplehood and parenthood weakens this reliance on informal support systems, which could also hinder mental health among older gay men (Shenkman et al., Citation2022). Within this social context, it is essential to further understand how vulnerability associated with older age and sexual minority status relates to mental health.

Research hypotheses

OHS will report higher evil-related threats in comparison to non-OHS.

Gay men will report higher evil-related threats in comparison to their heterosexual counterparts.

There will be an interaction between Holocaust background and sexual orientation on evil-related threats, such that OHS gay men will report higher evil-related threats in comparison to non-OHS gay men, and this effect will be stronger in comparison to the parallel gap between OHS and non-OHS heterosexual men.

Being OHS will have an indirect effect on depressive symptoms and life satisfaction through evil-related threats, and this indirect effect will be moderated by sexual orientation. Specifically, we hypothesized that among gay men, the indirect effect of evil-related threats in the relationship of being OHS with depressive symptoms and life satisfaction will be more pronounced when compared to this indirect effect among heterosexual men.

Method

Participants

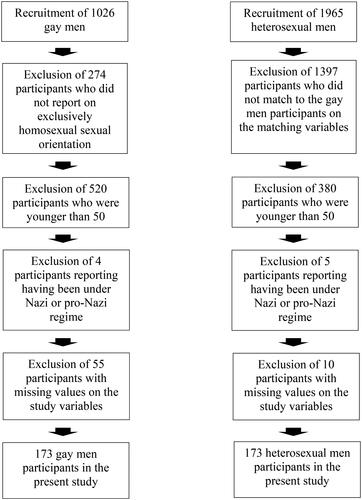

The present study conducted secondary analyses on data drawn from a larger project dealing with adaptation of middle-aged and older gay and heterosexual men (Shenkman et al., Citation2022). Participants were 173 middle-aged and older gay men (aged 50–84), including 43 (28.7%) who identified as OHS, along with pair-matched, 173 middle-aged and older heterosexual men (aged 50–86), including 38 (22.0%) who identified as OHS. A power analysis using the G*Power 3.1.9.6 software indicated that a minimum total sample size of 126 people would be needed to detect a medium effect size of partial η2 = 0.06 with a conventional power of 0.80 at 0.05 significance level, using an ANCOVA model with four groups and six covariates.

Gay men were called to participate in a study on happiness and sexual orientation via gay social groups, websites and venues. They were recruited in three sampling procedures: First, during 2010, in various social gay gatherings across Israel; second, during 2013, by targeting midlife and older gay men; and third, during 2016, by undergraduate psychology students that participated in a seminar on well-being among middle-aged and older gay men. Most gay men participants (80.9%) filled-in online questionnaires through the Qualtrics platform (www.qualtrics.com) while the rest filled-in printed questionnaires. In line with recommendations for studies on LGB older adults (Choi & Meyer, Citation2016), we set a minimum age of 50 for inclusion in the sample.

The heterosexual men group was drawn from general community samples of 1965 adults who participated in larger investigations on well-being during 2002-2016 (Shmotkin, Citation2020). These participants were recruited through a convenience sampling in a wide array of gathering sites across Israel. Most heterosexual men participants (n = 105, 60.7%) filled-in printed questionnaires while the rest filled-in online questionnaires through Qualtrics. presents the stages of participants’ selection to the gay and heterosexual men groups.

shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the gay and heterosexual men groups. Most participants in these groups were born in Israel, reported on above average or higher economic status, had an academic education, were living in a city, and were secular. Compared to the heterosexual participants, the gay men participants reported more years of education, were less likely to be in a steady relationship, and were more likely to live in a city and to be secular.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the gay and heterosexual men groups.

When compared, OHS participants were younger (M = 57.1, SD = 4.7) than non-OHS participants (M = 61.3, SD = 8.8), t(259.34) = 5.46, p < .001. No differences between OHS and non-OHS participants were found on economic status, education, country of birth, relationship status, place of residence, and religiousness, t(314) = −1.08, p = 0.280; t(314) = 0.27, p = 0.788; χ2(1) = 3.26, p = 0.071; χ2(1) = 0.55, p = 0.457; χ2(1) = 1.35, p = 0.245; χ2(1) = 2.39, p = 0.122, respectively.

Measures

Sociodemographic Questionnaire, with queries on the background characteristics appearing in .

Holocaust background

Participants were queried whether one or more of their parents had been in European areas governed by Nazi or pro-Nazi regimes during World War II. Identified as OHS were participants who answered yes to this question, and also denied having been under Nazi or pro-Nazi regime themselves. Identified as non-OHS were participants who answered no to the question regarding their parents as well as themselves.

Sexual orientation

Kinsey et al. (Citation1948) scale was used to assess sexual orientation on a self-rating scale ranging from 0 to 6. Gay men participants were identified by marking 6 (exclusively homosexual), and heterosexual men participants were identified by marking 0 (exclusively heterosexual).

Evil-related threats

This measure was derived from the full Hostile-World Scenario (HWS) Questionnaire (Shmotkin, Citation2005) which included 72 items measuring images of self-perceived threats to one’s life or integrity on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Evil-related threats were measured, within this questionnaire, by seven items concerning perceived threats of being exposed to evil or evil-laden conditions (see items in ), scored as the mean of item ratings, with higher scores referring to higher evil-related threats. These items were selected by three judges, acquainted with the HWS construct, who agreed upon the choice of items that corresponded to perceived evil. For a detailed description of the item selection, see Shmotkin and Bluvstein (Citation2024). Alpha coefficients of the evil-related threats scale in the current data were 0.69 and 0.65 among the gay and heterosexual men groups, respectively.

Table 2. Exploratory factor analysis of the evil-related threats scale.

In order to validate this measure among the present participants, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted on the measure’s items. Exploratory factor analysis, imposing a one-factor solution in principal component extraction with Varimax rotation (by SPSS 28), revealed factor loadings of 0.50 and higher for all seven items, and the explained variance was 33.67% (see ). Next, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted with maximum likelihood estimates (by AMOS 25). Missing data were treated by listwise deletion. Following common guidelines (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999), goodness of fit was assessed by several indices: Chi-Square (χ2), Bollen’s Increment Fit Index (IFI), Bentler’s Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Values higher than 0.95 in IFI and CFI, and values below 0.08 in RMSEA, were considered to indicate an acceptable fit. A model with the seven items loading on one factor yielded the following goodness-of-fit measures: Chi-Square = 38.46, df = 14, p < 0.001, IFI = 0.904, CFI = 0.901, RMSEA = .073. After allowing a correlation between the error variances of items of 58 and 29 as well of items 58 and 67, the goodness-of-fit measures improved: Chi-Square = 18.36, df = 12, p = 0.105, IFI = 0.975, CFI = 0.974, RMSEA = 0.040, showing adequate fit to the data.

Center for epidemiologic studies-depression scale (CES-D)

This 20-item self-report measure was designed to assess symptoms of depression (Radloff, Citation1977). Participants were asked to rate how often they had felt or behaved in a certain way in the past week (e.g. ‘I felt depressed’ and ‘I enjoyed life,’ the latter was one of four reverse-coded items) on a 1 (rarely or none of the time) to 4 (most or all of the time) scale. The measure’s score was the items’ mean rating where higher scores indicated more depressive symptoms. In the current study, alpha coefficients were 0.89 and 0.83 among the gay and heterosexual men groups, respectively. This instrument showed excellent psychometric properties in Israeli gay samples (e.g. Shenkman & Abramovitch, Citation2021).

Satisfaction with life scale (SWLS)

This 5-item measure aims to assess life satisfaction as the cognitive aspect of subjective well-being (Diener et al., Citation1985). Participants were asked to provide general judgments of their lives (e.g. ‘The conditions of my life are excellent’), rated on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale. The measure’s score was the items’ mean rating, where higher scores denoted higher satisfaction with life. Alpha coefficients in the present study were 0.84 and 0.86 among the gay and heterosexual men groups, respectively. This instrument showed excellent psychometric properties in Israeli gay samples (e.g. Shenkman & Abramovitch, Citation2021).

Procedure

In all the stages of recruitment described above, participants were informed that participation was voluntary and anonymous, and they checked the statement that they free-willingly gave their consent to participate in the study. They were given contact details of the researchers and were invited to write if any question arose, such that a more thorough debriefing could be done. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the authors’ institutions.

The matching procedure

In order to improve the comparability of the study groups, each gay participant was pair-matched with a corresponding individual in the general community samples, according to the following variables: place of birth, age, education level, and self-rated economic status. The matching was based on the ‘nearest neighbor matching’ technique (Stuart, Citation2010) such that the heterosexual group included participants who were most similar to the gay participants on the matching variables. By applying this technique, we sought to overcome some of the major difficulties inherent in the sampling and comparison of hidden populations (Meyer & Wilson, Citation2009).

Data analysis

The study hypotheses were tested in SPSS (version 28). First, Pearson correlations examined the correlations between the study variables among the gay and heterosexual men groups, separately. Second, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) examined the effects of Holocaust background (OHS versus non-OHS), sexual orientation (gay versus heterosexual men) and their interaction on evil-related threats while controlling for age, education, economic status, relationship status, place of residence, and religiousness. These covariates were selected because they differed between OHS and non-OHS, as well as sexual orientation, groups, and also due to their correlations with evil-related threats. Albeit being measured on ordinal scales, economic status and education were treated as continuous variables, as parametric tests were largely found unbiased when using similar ordinal variables (Norman, Citation2010).

Then, the PROCESS macro (Hayes, Citation2018) was used to examine whether the indirect effect of Holocaust background on depressive symptoms and life satisfaction through evil-related threats was moderated by sexual orientation, while controlling for the aforementioned covariates. To test conditional indirect effects, Hayes (Citation2018) method calculated 5,000 bootstrapped samples to estimate the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of these effects.

Results

Pearson and point biserial correlations among the study variables showed that evil-related threats correlated with more depressive symptoms and lower life satisfaction among the gay (r = 0.49, p < 0.001; r = −0.30, p < 0.001, respectively) and heterosexual (r = 0.46, p < 0.001; r = −0.35, p < 0.001, respectively) men groups. Moreover, while evil-related threats correlated with having a Holocaust background and with a lower likelihood of having a steady relationship among the gay men group (r = 0.24, p = 0.004; r = −0.21, p = 0.005, respectively), these associations were not found among the heterosexual men group (r = −0.02, p = 0.838; r = −0.09, p = 0.228, respectively). Furthermore, while evil-related threats correlated with lower economic status and lower education among the heterosexual men group (r = −0.41, p < 0.001; r = −0.29, p < 0.001, respectively), these associations were not found among the gay men group (r = −0.02, p = 0.827; r = −0.13, p = 0.080, respectively). In both groups, evil-related threats had no significant correlations with age, place of birth, place of residence, and religiousness. Remarkably, having a Holocaust background correlated with lower life satisfaction among the gay (r = −0.26, p = 0.001), but not among the heterosexual (r = −0.02, p = 0.808), men group. In both groups, having a Holocaust background had no significant correlations with depressive symptoms, place of birth, economic status, education, relationship status, place of residence, and religiousness.

The ANCOVA that examined the effects of Holocaust background and sexual orientation on evil-related threats, with six covariates controlled for (see Data Analysis), revealed a significant main effect for Holocaust background, such that OHS participants reported on higher evil-related threats compared to non-OHS participants, F(1, 306) = 3.88, p = 0.049, partial eta squared = 0.013 (see ). No main effect was found for sexual orientation, F(1, 306) = 0.59, p = 0.445, partial eta squared = .002. A significant interaction effect was found between Holocaust background and sexual orientation, F(1, 306) = 5.80, p = 0.017, partial eta squared = .019. Simple effect analyses showed that OHS gay men reported on higher evil-related threats compared to non-OHS gay men, F(1, 306) = 9.68, p = 0.002, partial eta squared = 0.031 (see ). No significant difference was found between OHS heterosexual men compared to non-OHS heterosexual men, F(1, 306) = 0.07, p = 0.789, partial eta squared = 0.000.

Table 3. Adjusted means of evil-related threats among the study groups.

Indirect effect analyses, conducted by the PROCESS macro (model 4) while controlling for the aforementioned covariates, indicated that among the entire sample, having a Holocaust background was associated with higher evil-related threats (beta = 0.11, p = 0.048), that in turn were associated with higher depressive symptoms (beta = 0.39, p < 0.001) and lower life satisfaction (beta = −0.20, p < 0.001). Holocaust background was associated with lower life satisfaction (beta = −0.14, p = 0.007), but not with depressive symptoms (beta = 0.07, p = 188), and the significance of these results did not change after controlling for evil-related threats. Notably, according to recent approaches that employ bootstrapping methods, a lack of significant association between presumably predicting and predicted variables does not preclude a possibly indirect effect between these variables (Hayes, Citation2009).

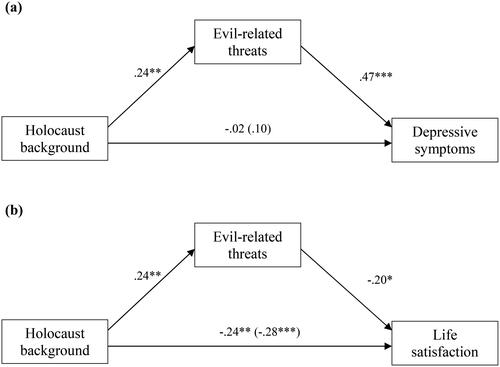

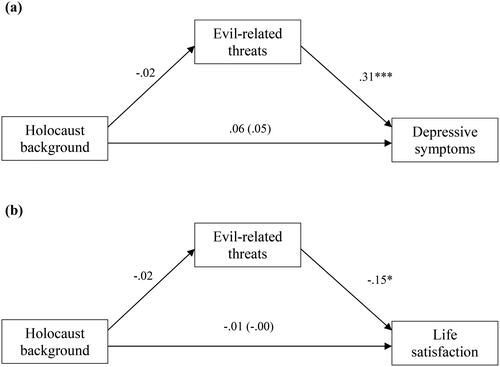

Examining the conditional indirect effect of Holocaust background on depressive symptoms through evil-related threats (model 7), the confidence intervals of the index of conditional indirect effect did not contain zero (index = 0.09, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.01, 0.17]) indicating a significant conditional indirect effect of sexual orientation. Following-up on this effect, the indirect effect was significant among gay men (b = 0.08, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.02, 0.15]), but not significant among heterosexual men (b = −0.01, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [-0.05, 0.04]). While examining the parallel indirect effect on life satisfaction (model 7), the confidence intervals of the index of conditional indirect effect did not contain zero (index = −0.05, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [-0.10, −0.00]) indicating a significant conditional indirect effect of sexual orientation. Following-up on this effect, the indirect effect was significant among gay men (b = −0.04, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [-0.09, −0.01]), but not significant among heterosexual men (b = 0.00, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [-0.02, 0.03]). and present the respective analyses of indirect effects for gay and heterosexual men.

Figure 2. The indirect effect of Holocaust background on depressive symptoms (a) and life satisfaction (b) through evil-related threats among gay men.

Notes. N = 150. Reported values are standardized regression coefficients (betas). Age, education, economic status, relationship status, place of residence, and religiousness served as covariates. The total effect of Holocaust background on depressive symptoms or life satisfaction is reported in parentheses.* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Figure 3. The indirect effect of Holocaust background on depressive symptoms (a) and life satisfaction (b) through evil-related threats among heterosexual men.

Notes. N = 166. Reported values are standardized regression coefficients (betas). Age, education, economic status, relationship status, place of residence, and religiousness served as covariates. The total effect of Holocaust background on depressive symptoms or life satisfaction is reported in parentheses.* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Discussion

Focusing on self-perceptions of evil-related threats, the current study juxtaposed effects of being descendant of Holocaust survivors and belonging to a sexual minority among middle-aged and older men. In accordance with our first hypothesis, OHS individuals reported stronger evil-related threats compared to non-OHS individuals. Contrary to our second hypothesis, there was no difference in evil-related threats between gay men and their heterosexual counterparts. As anticipated, a significant interaction between Holocaust background and sexual orientation on evil-related threats was observed. Specifically, OHS gay men reported stronger evil-related threats compared to non-OHS gay men, while among heterosexual men there was no significant difference between OHS and non-OHS on evil-related threats. Lastly, consistent with our fourth hypothesis, sexual orientation moderated the indirect effect of having a Holocaust background on depressive symptoms and life satisfaction through evil-related threats. Thus, there was a significant indirect effect of being OHS on depressive symptoms and life satisfaction through evil-related threats, but this effect was exclusive to gay men.

As predicted, OHS, compared to non-OHS, reported stronger evil-related threats, which were marked by an increased preoccupation with fear of human malevolence, including concerns about encountering terrorism, experiencing war, facing false accusations, enduring betrayal, or encountering a lack of support even from close individuals. This finding corroborates evidence of stronger, more generalized hostile-world scenarios among middle-aged and older OHS (Shrira, Citation2015). The heightened vigilance towards a hostile world among OHS individuals might indicate the incorporation of their parents’ worldview as shaped by the exposure to the traumas of the Holocaust (Danieli et al., Citation2017). Such intergenerational transmission could be actualized by child-rearing practices or familial communication patterns among the survivors, thus consciously or unconsciously conveying the message that the world was inherently hostile (Letzter-Pouw et al., Citation2014; Shrira, Citation2016).

Contrary to our second hypothesis, there was no significant difference in evil-related threats between gay men and their heterosexual counterparts. This finding diverges from earlier research indicating that individuals belonging to sexual minority groups might be more likely to perceive a heightened prominence of hostile-world scenarios (Shenkman & Shmotkin, Citation2013; Shenkman et al., Citation2020). One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that previous studies highlighting particular hostile-world scenarios for gay men predominantly focused on younger cohorts. Consequently, those studies might not accurately reflect perceptions of older gay men in terms of hostile-world scenarios. Additionally, while some research suggests that older sexual minority individuals face an elevated risk of physical and mental health vulnerabilities compared to heterosexual counterparts (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2012; Haarmann et al., Citation2024), other studies propose that sexual minority individuals develop a stronger capacity to cope with the challenges associated with aging, often referred to as ‘crisis competency.’ This term denotes the protective effect that the experiences and resilience developed during the ‘coming out’ process may confer against later-life crises (Kimmel, Citation2014). In the same vein, it has been postulated that sexual minority individuals acquire adeptness in dealing with stigma and prejudice throughout their lives, thus gaining enhanced resilience in their later years (Shenkman, Ifrah, et al., Citation2018). Researchers speculate that the opposing influences of minority stress and ‘crisis competency’ may offset each other (Shenkman, Ifrah, et al. Citation2022), resulting in no discernible differences in mental health between sexual minority and heterosexual older individuals. Presumably, the absence of disparity in evil-related threats between the current samples of gay and heterosexual older men may also be attributed to these factors.

Furthermore, it is plausible that disparities in mental health or evil-related threats between distinct populations become evident only under certain conditions of additional stress. Following this rationale, and in accordance with our third hypothesis, we observed a significant interaction between Holocaust background and sexual orientation concerning evil-related threats. Specifically, OHS gay men reported on stronger evil-related threats when compared to non-OHS gay men whereas the heterosexual counterparts showed no difference between OHS and non-OHS men. This outcome within the heterosexual men group aligns with previous research, which suggested that OHS individuals generally did not exhibit discernible differences in mental health when compared to their non-OHS counterparts (Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2003). Nevertheless, the significant difference in evil-related threats between OHS and non-OHS gay men may be attributed to a combination of stressors, namely, the sexual minority stress (Frost & Meyer, Citation2023) and the intergenerational traumatic impact stemming from the Holocaust (Shrira, Citation2023). Prior research has suggested that this amalgamation of stressors can manifest in unique hostile-world scenarios (Lifshitz et al., Citation2020), including in the interpersonal domain among OHS gay men (Shenkman, Shrira, et al., Citation2018).

This interplay between Holocaust background and sexual orientation further extends its effect on mental health outcomes, as the results concerning our fourth hypothesis show. Thus, sexual orientation moderated the indirect effect of a Holocaust background on both depressive symptoms and life satisfaction via evil-related threats. This conditional indirect effect by evil-related threats was evident among gay men, but not among heterosexual men. Accordingly, OHS, rather than non-OHS, gay men tended to perceive evil-related threats more strongly, and that, in turn, associated with higher depressive symptoms and lower life satisfaction. This pattern aligns with prior research that also examined how derivations of the hostile-world scenario model played roles of moderators or mediators in effects between life circumstances and mental health outcomes (Bergman et al., Citation2021; Shrira, Citation2015). In this line, past findings indicated that older OHS gay men reported increased interpersonal vulnerability and reduced satisfaction in their relationships compared to older non-OHS gay men. This vulnerability, in turn, was linked to less favorable mental health outcomes (Shenkman, Shrira, et al., Citation2018).

Collectively, our current findings, in conjunction with the previously mentioned research, suggest that the confluence of early family-based vulnerability compounded by the challenges of belonging to a sexual orientation minority may foster an environment where a more pronounced perception of a hostile world becomes prominent. This heightened perception, in turn, may be associated with adverse mental health outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

The present study presents several strengths. First, it conducted a pioneering investigation into the potential vulnerability associated with the notion of perceived evil and evil-related threats, focusing on their connections to mental health concomitants in a unique minority, namely older gay men whose parents were Holocaust survivors. This specific population has received scant attention in previous research. Second, unlike prior studies that selectively recruited OHS individuals, our study encountered them incidentally within a larger sample aimed at examining well-being and sexual orientation. This approach avoided the flaw in selectively sampling OHS individuals through various Holocaust-related affiliations, resulting in an overrepresentation of those profoundly influenced by intergenerational transmission of trauma (Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2003). Third, a distinctive aspect of this research was the use of individually-matched heterosexual counterparts as a reference group for gay men. The meticulous matching process involving background variables ensured a robust comparability between gay and heterosexual men.

Nevertheless, certain limitations of this study warrant acknowledgment. First, the study groups were not assembled through random or otherwise representative sampling methods, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings. Second, the participants’ involvement was analyzed solely with self-reported data, which possibly introduced self-presentational biases. Third, due to the correlational nature of the study, no causal relationships could be inferred from the observed associations. Another limitation pertained to the absence of specific measurements for traumatic stress, such as parental posttraumatic stress or secondary traumatization, which could be valuable in further exploring the intergenerational transmission of trauma. Moreover, future studies should explore the contribution of attitudes towards aging to the suggested models, as being old in the gay community, with its glorification of youth, might add additional stress to the studied population (Shenkman, Ifrah, et al., Citation2018). Also, as ethnicity was not directly assessed in the current study, we suggest that future studies further explore the contribution of ethnicity and origin to the investigated models. Additionally, the current investigation needs further extension into other sexual minorities, including lesbian, bisexual, and transgender individuals. Such a wider focus would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of evil-related concerns and their association with mental health in diverse sexual orientations.

Conclusion

This study stands as a pioneering effort to unveil the distinct susceptibility of middle-aged and older OHS gay men to evil-related threats. It elucidates the connections between such threats and adverse mental health outcomes. The theme of evil in facing perceived threats of a hostile world appears highly pertinent to remnants of familial trauma, as the Holocaust in this study, as well as to the experience of old age. The implications of the current findings hold particular relevance for counselors and clinicians working with middle-aged and older gay men, emphasizing the importance of considering multiple stressors, including traumatic background and sexual minority stress, in their therapeutic approach.

Our findings underscore the need for gerontological curricula that incorporate up-to-date information concerning the distinctive vulnerabilities, stressors, and resilience factors that characterize older sexual minorities. Such inclusion will better enable gerontologists to provide effective care and support to such unique, and often marginalized, segments of the populations.

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baider, L., Goldzweig, G., Ever-Hadani, P., & Peretz, T. (2006). Psychological distress and coping in breast cancer patients and healthy women whose parents survived the Holocaust. Psycho-oncology, 15(7), 635–646. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1010

- Bergman, Y. S., Shrira, A., Palgi, Y., & Shmotkin, D. (2021). The moderating role of the hostile-world scenario in the connections between COVID-19 worries, loneliness, and anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 645655. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.645655

- Berg-Warman, A., Resnizky, S., & Brodsky, J. (2018). Who cares for the caregiver? How the health services address the needs of family caregivers. Myers-JDC Brookdale Institute. [in Hebrew]

- Brom, D., Kfir, R., & Dasberg, H. (2001). A controlled double-blind study on children of Holocaust survivors. Israel Journal of Psychiatry, 38(1), 47–57.

- Choi, S. K., Meyer, I. H. (2016). LGBT aging: A review of research findings, needs, and policy implications. The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. https://www.lgbtagingcenter.org/resources/pdfs/LGBT-Aging-A-Review.pdf

- Danieli, Y., Norris, F. H., & Engdahl, B. (2017). A question of who, not if: Psychological disorders in Holocaust survivors’ children. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 9(Suppl 1), 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000192

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, G. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Emlet, C. A., Kim, H., Muraco, A., Erosheva, E., Goldsen, J., & Hoy-Ellis, C. P. (2012). The physical and mental health of lesbian, gay male, and bisexual (LGB) older adults: The role of key health indicators and risk and protective factors. Gerontologist, 53(4), 664–675. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns123

- Frost, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2023). Minority stress theory: Application, critique, and continued relevance. Current Opinion in Psychology, 51, 101579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101579

- Greenblatt-Kimron, L., Shrira, A., Ben-Ezra, M., & Palgi, Y. (2023). Echoes of ancestral trauma: Russo-Ukrainian War salience and psychological distress among subsequent generations in Holocaust survivor families. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001633

- Haarmann, L., Lieker, E., Folkerts, A.-K., Eichert, K., Neidlinger, M., Monsef, I., Skoetz, N., Träuble, B., & Kalbe, E. (2024). Higher risk of many physical health conditions in sexual minority men: Comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis in gay-and bisexual-identified compared with heterosexual-identified men. LGBT Health, 11(2), 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2023.008

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., McLaughlin, K. A., Keyes, K. M., & Hasin, D. S. (2010). The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health, 100(3), 452–459. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.168815

- Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford.

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Janoff-Bulman, R. (1989). Assumptive worlds and the stress of traumatic events: Applications of the schema construct. Social Cognition, 7(2), 113–136. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.1989.7.2.113

- Juni, S. (2016). Identity disorders of second-generation Holocaust survivors. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 21(3), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2015.1075802

- Kaplan, D. (2008). Commemorating a suspended death: Missing soldiers and national solidarity in Israel. American Ethnologist, 35(3), 413–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1425.2008.00043.x

- Kellermann, N. P. (2001). Perceived parental rearing behavior in children of Holocaust survivors. Israel Journal of Psychiatry, 38(1), 58–68.

- Kimmel, D. C. (2014). Theories of aging applied to LGBT older adults and their families. In N. A. Orel & C. A. Fruhauf (Eds.), The lives of LGBT older adults: Understanding challenges and resilience (pp. 73–90). American Psychological Association.

- Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Saunders.

- Lazar, R. (2016). Talking about evil – in retrospect: Trying to conceive the inconceivable. In R. Lazar (Ed.), Talking about evil: Psychoanalytic, social, and cultural perspectives (pp. 200–217). Routledge.

- Lehrner, A., & Yehuda, R. (2018). Trauma across generations and paths to adaptation and resilience. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 10(1), 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000302

- Letzter-Pouw, S. E., Shrira, A., Ben-Ezra, M., & Palgi, Y. (2014). Trauma transmission through perceived parental burden among Holocaust survivors’ offspring and grandchildren. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(4), 420–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033741

- Lifshitz, R., Ifrah, K., Markovitz, N., & Shmotkin, D. (2020). Do past and prospective adversities intersect? Distinct effects of cumulative adversity and the hostile-world scenario on functioning at later life. Aging & Mental Health, 24(7), 1116–1125. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1597014

- Meyer, I. H., & Wilson, P. A. (2009). Sampling lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(1), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014587

- Norman, G. (2010). Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 15(5), 625–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9222-y

- Nys, T., & de Wijze, S. (Eds.). (2019). The Routledge handbook of the philosophy of evil. Routledge.

- Palgi, Y., Shrira, A., & Ben-Ezra, M. (2015). Family involvement and Holocaust salience among offspring and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 13(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2015.992902

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

- Sagi-Schwartz, A., Van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2008). Does intergenerational transmission of trauma skip a generation? No meta-analytic evidence for tertiary traumatization with third generation of Holocaust survivors. Attachment & Human Development, 10(2), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730802113661

- Shenkman, G., & Abramovitch, M. (2021). Estimated likelihood of parenthood and its association with psychological well-being among sexual minorities and heterosexual counterparts. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 18(2), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00451-z

- Shenkman, G., & Shmotkin, D. (2013). The hostile-world scenario among Israeli homosexual adolescents and young adults. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(7), 1408–1417. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12097

- Shenkman, G., Ifrah, K., & Shmotkin, D. (2018). Meaning in life among middle-aged and older gay and heterosexual fathers. Journal of Family Issues, 39(7), 2155–2173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X17741922

- Shenkman, G., Ifrah, K., & Shmotkin, D. (2020). Interpersonal vulnerability and its association with depressive symptoms among gay and heterosexual men. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 17(2), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00383-3

- Shenkman, G., Ifrah, K., & Shmotkin, D. (2022). The moderation of socio-demographics in physical and mental health disparities among Israeli gay and heterosexual middle-aged and older men. Aging & Mental Health, 26(5), 1061–1068. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1901259

- Shenkman, G., Segal-Engelchin, D., & Taubman-Ben-Ari, O. (2022). What we know and what remains to be explored about LGBTQ parent families in Israel: A sociocultural perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074355

- Shenkman, G., Shrira, A., Ifrah, K., & Shmotkin, D. (2018). Interpersonal vulnerability among offspring of Holocaust survivors gay men and its association with depressive symptoms and life satisfaction. Psychiatry Research, 259, 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.10.017

- Shmotkin, D. (2005). Happiness in the face of adversity: Reformulating the dynamic and modular bases of subjective well-being. Review of General Psychology, 9(4), 291–325. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.4.291

- Shmotkin, D. (2011). The pursuit of happiness: Alternative conceptions of subjective well-being. In L. W. Poon, & J. Cohen-Mansfield (Eds.), Understanding well-being in the oldest old (pp. 27–45). Cambridge University Press.

- Shmotkin, D. (2020). Establishing the concept of hostile-world scenario: The imaging of critical threats in life. Unpublished report.

- Shmotkin, D., & Bluvstein, I. (2024). Inquiry on threats of evil within the hostile-world scenario: Emerging content and mental health concomitants among Holocaust survivors. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. Paper accepted for publication.

- Shmotkin, D., Avidor, S., & Shrira, A. (2016). The role of the hostile-world scenario in predicting physical and mental health outcomes in older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 28(5), 863–889. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264315614005

- Shokeid, M. (2003). Closeted cosmopolitans: Israeli gays between center and periphery. Global Networks, 3(3), 387–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/14710374.00068

- Shrira, A. (2015). Transmitting the sum of all fears: Iranian nuclear threat salience among offspring of Holocaust survivors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 7(4), 364–371. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000029

- Shrira, A. (2016). Perceptions of aging among middle-aged offspring of traumatized parents: The effects of parental Holocaust-related communication and secondary traumatization. Aging & Mental Health, 20(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1013921

- Shrira, A. (2023). Late-life manifestations of ancestral trauma: The case of older adult offspring of Holocaust survivors. In J. T. Baumel-Schwartz & A. Shrira (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of multidisciplinary perspectives on descendants of Holocaust survivors (pp. 182–191). Routledge.

- Stuart, E. A. (2010). Matching methods for causal inference: A review and a look forward. Statistical Science: A Review Journal of the Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 25(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1214/09-STS313

- Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Sagi-Schwartz, A. (2003). Are children of Holocaust survivors less well-adapted? A meta-analytic investigation of secondary traumatization. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16(5), 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025706427300

- Wen, G., & Zheng, L. (2019). The influence of internalized homophobia on health-related quality of life and life satisfaction among gay and bisexual men in China. American Journal of Men’s Health, 13(4), 1557988319864775. https://doi.org/10.1177/155798831986477

- Wiseman, H., & Barber, J. P. (2008). Echoes of the trauma: Relational themes and emotions in children of Holocaust survivors. Cambridge University Press.