Abstract

Objectives

Loneliness is associated with maladaptive cognitions, yet little is known about the association between loneliness and intrusive thinking during older adulthood. Links between loneliness and intrusive thoughts may be particularly strong among individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), who may have greater difficulty regulating emotion and intrusive thoughts. In contrast, having close relationships (e.g. being married) may serve as a protective factor as marital status is associated with better overall well-being.

Method

Participants were 316 older adults (recruited from the Bronx, NY, as part of a larger study) without dementia at study intake (40% Black; 13% Hispanic, Mage = 77.45 years, 67% women) who completed ecological momentary assessments five times daily for 14 consecutive days (13,957 EMAs total). Multilevel modeling was used to examine the association between momentary loneliness and intrusive thoughts and whether MCI and marital status interacted to moderate this association.

Results

There was a significant three-way interaction (β = −0.17, p < 0.05), such that lagged momentary loneliness was positively associated with intrusive thoughts (3–4 h later) for those with MCI who were not married.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that among older adults with MCI, being married may be a protective factor and being unmarried may be a risk factor for experiencing loneliness and subsequent intrusive thoughts.

Loneliness is a subjective and distressing feeling that can negatively affect health and well-being during older adulthood (Courtin & Knapp, Citation2017; Ong et al. Citation2016). Characterized by a perceived discrepancy between desired and actual social relationships (Peplau & Perlman, Citation1982), loneliness is distinct from objective social isolation (Smith & Victor, Citation2019) and often predicts health outcomes separately from objective measures of social isolation (Cacioppo et al. Citation2015; O’Súilleabháin et al. Citation2019). Recent work suggests that one in four older adults is lonely (Chawla et al. Citation2021) and there is abundant research on the negative mental and physical health outcomes tied to loneliness, including depression (Martín-María et al. Citation2021), functional decline (Perissinotto et al. Citation2012), cardiovascular disease (Holt-Lunstad & Smith, Citation2016), and mortality (Holt-Lunstad et al. Citation2015), and Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) (Lara et al. Citation2019; Sundström et al. Citation2020). Because loneliness is a major public health concern, particularly during later life (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, Citation2020), it is important to investigate loneliness as it is experienced in everyday life to better understand potential mechanisms and consequences linked to chronic loneliness, as well as potential individual differences related to these associations. As such, the goal of the present research was to examine the association between older adults’ loneliness and intrusive thinking, and to examine critical individual differences that may induce susceptibility or promote resilience in the face of loneliness and intrusive thinking.

Loneliness and intrusive thoughts

Unresolved loneliness is theoretically proposed to elicit a regulatory loop of thoughts and behaviors that perpetuate and prolong existing feelings of loneliness (Cacioppo & Hawkley, Citation2009). One such behavior that may play an important role in loneliness is intrusive thinking. Intrusive thoughts—defined as unwanted, difficult to control, repeatedly occurring, and generally accompanied by distress (Munoz et al. Citation2013; Rachman, Citation1981)—are considered a maladaptive stress response (Clark, Citation2005; Kuhl & Baumann, Citation2013) and are related to emotion regulation (Joormann & Quinn, Citation2014). The content of intrusive thoughts may differ by valence (i.e. positive, negative, or neutral thoughts) and can be related or unrelated to specific stressors or one’s current activity (Brose et al. Citation2011; Sarason et al. Citation2014).

Loneliness may tax cognitive resources necessary for self-regulation (e.g. Mansueto et al. Citation2022; Vohs & Baumeister, Citation2016), paving the way for uncontrollable intrusive thoughts. In turn, having heightened intrusive thoughts may increase risk for chronic loneliness over time, hindering opportunities to develop and maintain positive social connections and relationships with others (Heinrich & Gullone, Citation2006). Research has found that on days when negative affect and daily stress were higher than typical, intrusive thoughts were also higher among older adults in daily life (Stawski et al. Citation2011). However, there is limited evidence on the association between loneliness and intrusive thoughts per se, which might be particularly informative for theory and interventions for loneliness. The only study that has specifically assessed the association between intrusive thinking and loneliness found no significant relationship (Cacioppo et al. Citation2006), but this study was conducted cross-sectionally among young adults and only assessed intrusive thoughts that were specific to past traumatic events. Hence, the association between feelings of loneliness and subsequent intrusive thoughts as they naturally occur in daily life is unknown among older adults. This association is important to understand among older adults, who may have vulnerabilities surrounding loneliness. Given that the theoretical regulatory loop of loneliness (Cacioppo & Hawkley, Citation2009) is a process unfolding within an individual (i.e. feelings of loneliness relate to later thoughts and behaviors for a given person), it is also critical to examine within-person associations temporally and in everyday life.

Investigating feelings of loneliness and intrusive thoughts using ecological momentary assessment (EMA) methodology provides a closer look at these phenomena as they occur naturally in daily life, including fluctuations in states across repeated assessments. Through repeated assessments, EMA allows for the fine-grained detection of fluctuations within a person (i.e. intraindividual variability), which may otherwise be lost in one-time assessments. Although research on momentary loneliness among older adults is beginning to grow (e.g. Compernolle et al. Citation2021, Citation2022; Fingerman et al. Citation2022; Goldman & Compernolle, Citation2023; Van Bogart et al. Citation2023; Zhaoyang et al. Citation2021), the association between loneliness and intrusive thoughts has not been examined in a moment-to-moment fashion using EMA. Examining shorter-term variations in loneliness and related thoughts and feelings during later life may yield unique indicators of moments when interventions may be most effective in daily life.

Although both theoretical and empirical evidence suggests older adults are generally more emotionally stable than younger adults (Burr et al. Citation2021; Carstensen et al. Citation2011; Charles, Citation2010), older adults may be more vulnerable to experiencing shifts in mood or affect in certain contexts in everyday life (Mroczek & Almeida, Citation2004; Stawski et al. Citation2019). The model of Strength and Vulnerability Integration (SAVI; Charles, Citation2010) and the Cognitive Control Model (Knight et al. Citation2007) suggest older adults might experience unique unavoidable stressors (e.g. declining memory or other cognitive ability) that can disrupt age-related benefits of emotion regulation. As such, better understanding how loneliness and intrusive thinking are associated across moments in daily life may provide crucial information about older adult emotion regulation in the context of loneliness.

The interactive roles of mild cognitive impairment and marital status in the association between momentary loneliness and intrusive thinking

Not only is it important to better understand the association between loneliness and intrusive thinking in daily life, but it is also critical to investigate for whom this association is pronounced. A key factor that may explain variation in how momentary loneliness and intrusive thoughts are connected is mild cognitive impairment (MCI), which often represents a transitional stage between normal aging and dementia. The notion that loneliness is linked with intrusive thoughts among older adults aligns with the Cognitive Debt Hypothesis. This hypothesis posits that repetitive negative thinking, like that of intrusive thinking, underlies many psychosocial risk factors that contribute to the development of ADRD (Marchant & Howard, Citation2015). MCI is clinically significant as it is associated with a greatly heightened risk of progression to dementia, making it a critical period for intervention (Roberts et al. Citation2014). Individuals with MCI may experience emotional and behavioral changes, including an increased vulnerability to loneliness (McCade et al. Citation2011; Yu et al. Citation2016). Thus, individuals with MCI may be at heightened risk for experiencing intrusive thoughts following lonelier moments in daily life.

It is also critical to investigate whether certain sociodemographic characteristics may protect or exacerbate connections between intrusive thinking and loneliness among older adults. As related research suggests that loneliness may be experienced less among those who have a stable close relationship (Hawkley et al. Citation2008), being married may serve as a protective factor in the link between loneliness and intrusive thinking. Marital status appears to be a strong predictor of loneliness in older adulthood (e.g. Dahlberg et al. Citation2022; Page & Cole, Citation1991), with several studies showing that married older adults tend to report feeling less lonely than their non-married counterparts (e.g. Kislev, Citation2022; Nicolaisen & Thorsen, Citation2014; Pikhartova et al. Citation2016). Marital status may provide a basic indication of social support available (e.g. emotional or instrumental support)—support that is imperative for maintaining cognitive health into late adulthood. Relatedly, married older adults tend to have lower rates of cognitive impairment and dementia compared to divorced and widowed older adults (e.g. Håkansson et al. Citation2009; Liu et al. Citation2019). Thus, examining the interaction of MCI and marital status on the association between loneliness and intrusive thoughts may shed light on particular subgroups of individuals who may be more or less at risk for negative outcomes related to chronic loneliness or worse cognition.

Taken together, additional research is needed to assess the potential interactive roles that MCI and marital status play in the association between loneliness and intrusive thinking. Examining these associations will not only give us insight into daily cognitive and emotional experiences of married and non-married older adults with MCI but may also help identify individuals who are at greater risk for the negative cyclical effects of loneliness.

Current study

The current research aims to address a gap in the literature regarding how momentary loneliness relates to intrusive thoughts in daily life among older adults, and whether this association varies based on the interactive roles of MCI and marital status. Driven by the theoretical regulatory loop of loneliness (Cacioppo & Hawkley, Citation2009), we hypothesized that momentary loneliness would be associated with higher levels of intrusive thoughts several hours later (Hypothesis 1). Further, given that MCI is a cognitive stressor that affects older adults, and being unmarried during later life is associated with higher levels of loneliness and worse cognitive health, we hypothesized that associations between loneliness and subsequent intrusive thoughts would be strongest for unmarried individuals with MCI (Hypothesis 2).

Method

Participants and procedure

The current sample was drawn from the most recently collected wave of data collection from the ongoing Einstein Aging Study, collected between May 2017 and March 2020 (i.e. before the announcement by the World Health Organization of the COVID-19 pandemic on 11 March 2020). The Einstein Aging Study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Participants were recruited via systematic random sampling of Medicare and New York Registered Voter Lists in Bronx County, New York. Phone screenings were conducted to determine eligibility (e.g. aged 70 years or older, ambulatory, English-speaking). Exclusion criteria at study intake included significant hearing or vision loss, current substance abuse, severe psychiatric symptoms, chronic medicinal use of opioids or glucocorticoids, treatment for cancer within the last 12 months, and a diagnosis of dementiaFootnote1). Eligible participants provided consent, visited the research clinic to complete demographic and psychosocial questionnaires, and received EMA protocol training. The EMA protocol included self-initiated wake-up and end-of-day surveys and four quasi-random beeped surveys (approximately 3.5 h apart) completed via smartphones; morning surveys were not included in the current analyses, as they did not assess loneliness or intrusive thoughts. Participants completed two practice days of EMA before beginning the formal 14-day EMA protocol (Zhaoyang et al. Citation2021 for additional procedural details).

The current study included 316 older adults ( for participant characteristics), with complete data from baseline assessments of demographic and psychosocial variables and EMA beeped surveys across 14 days. These participants completed 13,957 momentary assessments across the EMA period. For the entire study protocol, participants were generally highly compliant, with 83.38% of all EMAs completed and 80.26% of all end-of-day surveys completed. The current compliance rates are in line with prior studies that have found strong support for the feasibility and application of EMA in older samples of healthy adults and people with clinical disorders (Cain et al. Citation2009; Moore et al. Citation2017). For the specific EMAs used in the current analytic sample (loneliness and intrusive thoughts), compliance was excellent (i.e. less than 1% missing across all EMAs).

Table 1. Descriptive information on participant characteristics (N = 316).

Measures

Momentary loneliness and intrusive thoughts

At each EMA, participants answered, ‘Right now, do you feel lonely?’ using a slider scale between Not at all (0) and Extremely (100). Unspecific intrusive thoughts were measured with the item, ‘In the past five minutes, were you having a train of thought that you couldn’t get out of your head?’ using a slider scale of Not at all (0) to Very Much (100). This item was chosen to capture unspecific intrusive thoughts similar in content to items that previous research has used (e.g. Brose et al. Citation2011). Single-item measures have been shown to be reliable in the context of loneliness (Mund et al. Citation2023) and other self-reported psychological variables using intensive repeated assessments (Allen et al. Citation2022; Dejonckheere et al. Citation2022; Song et al. Citation2023).

MCI and marital status

The MCI status of each participant was determined using Jak/Bondi criteria (Jak et al. Citation2009) and then coded as no MCI (0) and MCI (1) for analyses. Participants completed two neuropsychological tests related to each of the five cognitive domains: memory, executive function, attention, language, and visuospatial processing. Criteria for MCI status included (1) impaired scores (>1 SD below the age, gender/sex, and education adjusted normative mean) on both measures within at least one cognitive domain; or (2) impaired score on one measure in three of the five domains; or (3) reported functional declines assessed by the instrumental activities of daily living scale (IADL)Footnote2.

Marital status was assessed using the question, ‘What is your current marital status?’ Response options included: married, separated, widowed, divorced (not remarried), and never married. For the current analyses, marital status was coded as Married (1) or Any other status (0). We acknowledge there are conceptual differences between different categorizations of ‘unmarried’ (widowed, divorced, never married); however, given the sample size (N = 316), and the number of participants who were married (n = 106), we chose to operationalize marital status dichotomously to maximize power.

Covariates

Because both loneliness and intrusive thoughts might relate to depressed mood (Cacioppo et al. Citation2006), momentary depressed mood (both lagged and concurrent levels) and concurrent levels of loneliness were included as covariates to determine whether the association between momentary loneliness and subsequent intrusive thoughts was independent of these factors. For momentary depressed mood, participants answered, ‘Right now, do you feel depressed/blue?’ using a slider scale of Not at all (0) to Extremely (100).

Covariates in sensitivity analyses

Several other covariates were considered for sensitivity analyses. Momentary anxiety was assessed with the EMA item, ‘Right now, do you feel tense/anxious?’ and participants answered with a slider scale beginning with Not at all (0) and ending with Extremely (100). Participants reported the valence of their thoughts at each momentary assessment in response to the item, ‘In the last 5 min, what type of thoughts were you having?’ on a scale of Unpleasant (0) to Pleasant (100). Presence/absence of others at the time of each EMA was measured with the question, ‘Who are you with?’ Responses were coded as With Nobody (1) or With Others (0). Others included any of the following: spouse/partner, children, other family members, friends, neighbors, acquaintances, strangers, pets, other people. Gender/sex was coded as Women (0) and Men (1)Footnote3. Participants’ self-reported race/ethnicity was coded as other (0) and White (1); (other included Black/African American, White Hispanic, Black Hispanic, Asian, and otherFootnote4). Educational status was self-reported years of education. Living arrangement was coded as Lives with others (0) or Lives alone (1).

Analytic plan

Using multilevel modeling, we examined the association between momentary loneliness and intrusive thoughts from one momentary assessment to the next (i.e. momentary loneliness was lagged to predict intrusive thoughts approximately 3–4 h later), and the interactive moderation of this association by marital status and MCI status. A power analysis conducted via simulation methods using Mplus Version 8.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–Citation2017) indicated there was 80% power to detect a small effect size (−0.145) for this three-way interaction given our sample size and number of EMA timepoints. Autocorrelated residuals were included in the model to account for the possibility that intrusive thoughts are influenced by levels at the previous assessment. Models were estimated with random intercepts and slopes for loneliness. For model convergence, correlations among the random effects were fixed to zero. We used within-person centered predictor values to test how a higher momentary score of loneliness than is typical for a given person is associated with intrusive thoughts at the next EMA. The within-person centered value was created by subtracting each person’s mean value from their own momentary values. Covariates were momentary depressed mood (lagged and concurrent) and concurrent momentary loneliness.

Lastly, sensitivity analyses were conducted to probe the results based on the inclusion of other potentially relevant variables in the model. Levels of concurrent and lagged momentary anxiety and momentary thought valence (unpleasant, pleasant) were added as covariates to the model to examine associations above and beyond other related dysphoric states. To examine whether relationship type differed (e.g. spouse versus roommate), marital status was replaced with living arrangement (living alone versus with others). Finally, moderation by demographic factors (gender/sex, race/ethnicity, education) and thought valence was explored.

Results

Sample characteristics

The analytic sample included 316 individuals, with a mean age of 77.45 years (SD = 4.83 years) and who did not significantly differ in key sociodemographic factors (including gender/sex, race/ethnicity) across MCI groups or marital status. Among those with MCI (n = 101), there were 68 women and 33 men. Among those who were married (n = 106), there were 39 women and 67 men (see for additional sample characteristics). Married individuals reported significantly lower average levels of momentary loneliness than nonmarried individuals [t (314) = 3.06, p < 0.01)]. Levels of intrusive thoughts across the EMA protocol did not significantly vary by marital status. Individuals with MCI were not significantly more likely to be married (χ2 (1, N = 316) = 1.49, p = 0.22), had non-significantly higher average levels of loneliness (Welch’s t (211) = −1.59, p = 0.11), and reported significantly more intrusive thoughts (Welch’s t (168) = −2.66, p = 0.01). Intraclass correlations for momentary loneliness (ICC = 0.747) and intrusive thoughts (ICC = 0.563) revealed that 25.3–43.7% of the variation in these variables was at the within-person level. This amount of variation at the within-person level suggests that, although momentary loneliness and intrusive thoughts are relatively stable for the current sample, individuals vary from their own typical levels across EMAs throughout the day.

Effects of lagged loneliness on intrusive thoughts

Higher than typical levels of loneliness at one assessment were associated with higher levels of intrusive thoughts at the next assessment, controlling for lagged and concurrent levels of depressed mood and levels of concurrent loneliness (β = 0.04, p = 0.03). For completeness, given the possibility of bidirectional associations, an exploratory follow-up analysis revealed this association was not significant in the opposite direction (i.e. higher than average intrusive thoughts did not predict higher levels of loneliness at the next assessment among the total sample (β = −0.00, p = 0.84) as well as among the subset of participants with MCI (β = −0.01, p = 0.51).

Interaction of MCI status, marital status, and lagged loneliness on intrusive thoughts

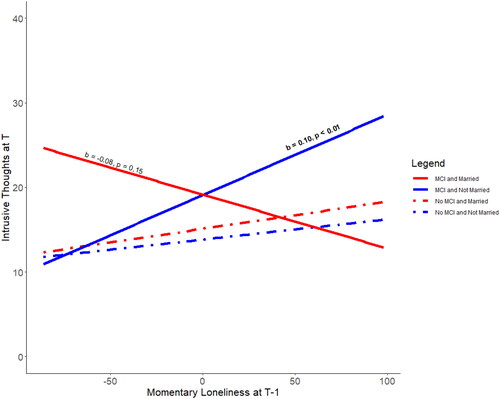

There was a significant three-way interaction between MCI status, marital status, and lagged loneliness (β = −0.17, p = 0.03). Results remained significant with and without covariatesFootnote5. As shown in () for individuals without MCI, the observed association between loneliness and intrusive thoughts did not significantly differ by marital status (married: β = 0.03, p = 0.52; not married: β = 0.03, p = 0.26). However, the association between loneliness and intrusive thoughts did significantly differ by marital status for individuals with MCI. Specifically, for individuals with MCI who were not married, higher than typical levels of loneliness at one assessment were significantly associated with higher levels of intrusive thoughts at the following assessment (β = 0.10, p < 0.01); For individuals with MCI who were married, higher than typical levels of loneliness at one assessment were associated with lower levels of intrusive thoughts at the following assessment, although this association was not significant (β = −0.08, p = 0.15).

Figure 1. MCI Status, marital status, and lagged loneliness interact to predict intrusive thoughts. Note. T: momentary assessment; T − 1: previous momentary assessment (i.e., 3–4 hours before T); significant slopes are bolded (neither dashed lines are significant); N’s for each group: MCI and married (29), MCI and not married (72), No MCI and married (77), No MCI and not married (139).

Table 2. Interaction of MCI status, marital status, and lagged loneliness on intrusive thoughts.

Results of sensitivity analyses

When both concurrent and lagged momentary anxiety were added to the interaction model, the above results remained significant (β = −0.17, p = 0.02). Additionally, when thought valence and presence/absence of others were added to the model separately as covariates, results remained significant (β = −0.15, p = 0.04; β = −0.17, p = 0.02, respectively). When marital status was replaced with living arrangement (living alone or with others), results were no longer significant (β = 0.11, p = 0.11). Separate moderation analyses examining demographic factors (gender/sex, race/ethnicity, education) revealed no significant group differences in the three-way interaction. Lastly, moderation by thought valence did not reveal significant differences. Full model results are provided as Supplementary Tables.

Discussion

Investigations of momentary loneliness among older adults are growing but remain limited. Examining momentary connections between loneliness and maladaptive cognitions, such as intrusive thinking, is critical for better understanding daily experiences of older adults and for determining who may be at greater risk for experiencing chronic loneliness and worsening cognition. The present work addressed this gap in the literature by examining the within-person association between loneliness and subsequent intrusive thoughts in daily life among older adults and whether MCI and marital status interacted to predict these associations. Results suggest a marital relationship may serve as a protective factor for those with MCI and that unmarried older adults with MCI may be at greater risk for experiencing intrusive thoughts following lonelier moments, even when controlling for depressed mood and concurrent levels of loneliness.

Our findings shed light on momentary processes that occur during older adulthood. We found evidence for a significant within-person association between higher momentary loneliness and higher levels of intrusive thoughts 3–4 h later; this was not accounted for by concurrent or lagged levels of depressed mood or anxiety, or concurrent levels of loneliness. Furthermore, this association was not significant in the opposite direction. Although the current results are correlational, this finding aligns with past theoretical and empirical work which suggests that loneliness can elicit a regulatory loop of negative cognitions and behaviors (Cacioppo & Hawkley, Citation2009) in ways that may be cognitively taxing. Momentary, within-person examination provides information about what happens when a person feels lonelier than is typical for themselves, as opposed to comparing one person to another. This lens of investigation allows researchers to test processes within the regulatory loop of loneliness across time, and the potential development of chronic loneliness. The current work may serve as an important step toward investigating loneliness in daily life and to inform future work to delineate how momentary associations relate to longer term patterns of loneliness, cognitive decline, and dementia risk.

The present work also sheds light on key potential risk and resilience factors related to the link between momentary loneliness and intrusive thoughts. Findings suggest that being married may offer some protection for older individuals with MCI against the association between loneliness and intrusive thinking. Marriage can provide multiple benefits to well-being including emotional connection, financial security, and social support (e.g. informational, instrumental), with the protective role of marriage on mental health seeming to stem from the social integration that the relationship affords (Cutright et al. Citation2006, Citation2007). It is possible that spouses of individuals with MCI help with daily emotion and thought regulation. Indeed, spouses may take on a caregiving role for individuals with MCI (Pasymowski et al. Citation2013), which may help offset loneliness, cognitive overload, and intrusive thoughts. Moreover, although being married introduces the likelihood of spousal arguments and conflicts to some degree (Birditt et al. Citation2005), spouses may aid in managing emotional needs that may be useful for buffering associations between loneliness and intrusive thoughts. In comparison, older adults without a spouse may lack the social resources needed to combat negative feelings and behaviors; this may be particularly problematic among individuals with MCI. The temporal specificity of the interaction in the current work emphasizes the importance of studying within-person processes in addition to examining between-person differences (Molenaar, Citation2004).

The observed findings were specific to marital status, as we did not replicate the observed findings when living status (living alone vs. with others) was examined in the same manner. These findings suggest there is something unique about a marital relationship that provides more benefits to individuals living with MCI than living with another person, generally. Although additional research is needed to document and understand nuances in how such factors relate to loneliness (including how associations play out among couples, and over time), the present research indicates that there may be great value in doing so to inform targeted interventions. For example, better understanding aspects of marriage that are protective for those with MCI with regard to loneliness and intrusive thoughts may elucidate ways to support unmarried individuals with MCI, including those who are widowed/bereaved.

Follow-up sensitivity analyses provided additional information to our findings. Thought valence (pleasant or unpleasant) did not play a role in the association between loneliness and intrusive thoughts (as a moderator or as a control variable). This is unsurprising in that unwanted thoughts of any type can serve as an index of poorer self-regulation. Even if a thought is positive (e.g. ‘I can’t wait to watch my favorite show tonight!’), if the thought is unwanted, this may indicate attentional control issues. Controlling for the presence/absence of others at the time of EMA also yielded unchanged results. This emphasizes the conceptual distinction between loneliness and social isolation, such that the presence of others (broadly) may not be related to the subjective feeling of loneliness and subsequent intrusive thoughts. Moderation by gender/sex, race/ethnicity (as a dichotomized variable), and education level yielded null results. Although the current sample was diverse (e.g. 40% Black; 13% Hispanic, 67% women), due to sample size we were unable to examine moderation within particular subgroups (e.g. within Hispanic individuals) who may have different lived experiences. Future research might test these associations in larger subsamples.

Another limitation of the present work is that we were not powered to examine how relationship quality indicators played a role in the association between loneliness and intrusive thoughts. This would be a valuable addition to future research, as would be exploration of other situational living arrangements that may influence the observed links. Although uncommon among the current generation of older adults (Stepler, Citation2016) and not assessed in the current study, some individuals may be married but live separately. Examining differences between marital status subtypes (e.g. separated, widowed, divorced, never married) would also be a worthy pursuit to further delineate individuals at risk for chronic loneliness. Lastly, it would be valuable for future research to incorporate the analysis of daily stress and/or additional aspects of social context into the study of loneliness and intrusive thoughts, given that stress is linked with loneliness (Kang et al. Citation2023) and social situations can vary dramatically in daily life (Zhaoyang et al. Citation2018).

Conclusion

In this study, higher levels of intrusive thoughts were reported 3–4 h following lonelier moments in daily life. This finding was largely driven by individuals with MCI who were not married. These findings were robust to the inclusion of levels of lagged and concurrent depressed mood and concurrent loneliness. Further, sensitivity analyses revealed findings were also robust to the inclusion of levels of lagged and concurrent anxiety and concurrent thought valence, providing stronger evidence of the temporal connection between loneliness and intrusive thoughts above and beyond other related dysphoric attributes. Separate follow-up moderation analyses revealed no demographic group differences (gender/sex, race/ethnicity, education) in the current associations. Findings in older adults with MCI suggest that being married may be a protective factor for intrusive thoughts following lonelier moments in daily life; in the same manner, being unmarried may be a risk factor. Given these associations, marital status might be an important predictive factor for both cognitive performance and the eventual cognitive trajectory of individuals with MCI. Further research is needed to better understand the protective characteristics of a marital relationship in the context of loneliness and cognitive control during everyday life for those with MCI, and to examine later associations with chronic loneliness and cognitive health.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (50.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Dementia diagnosis was based on the DSM-IV standardized clinical criteria. For more information on the larger study methods, please see Katz et al. (Citation2021).

2 For more details on use of this criteria in other published work, see Zhaoyang et al. (Citation2021).

3 We use the term “gender/sex” because no participants in the present work reported non-binary or transgender identities and the differentiation between biological and sociocultural factors related to gender/sex was not possible.

4 Although we were not adequately powered to examine differences across different groups of racial or ethnic identities, the dichotomized covariate enabled us to covary and explore moderation based on a proxy of minoritized experience.

5 Model results without controlling for momentary depressed mood (lagged and concurrent) and concurrent momentary loneliness: (β = −0.17, p = .04).

References

- Allen, M. S., Iliescu, D., & Greiff, S. (2022). Single item measures in psychological science: A call to action [Editorial]. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 38(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000699

- Birditt, K. S., Fingerman, K. L., & Almeida, D. M. (2005). Age differences in exposure and reactions to interpersonal tensions: A daily diary study. Psychology and Aging, 20(2), 330–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.20.2.330

- Brose, A., Schmiedek, F., Lövdén, M., & Lindenberger, U. (2011). Normal aging dampens the link between intrusive thoughts and negative affect in reaction to daily stressors. Psychology and Aging, 26(2), 488–502. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022287

- Burr, D. A., Castrellon, J. J., Zald, D. H., & Samanez-Larkin, G. R. (2021). Emotion dynamics across adulthood in everyday life: Older adults are more emotionally stable and better at regulating desires. Emotion, 21(3), 453–464. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000734

- Cacioppo, J. T., Cacioppo, S., Capitanio, J. P., & Cole, S. W. (2015). The neuroendocrinology of social isolation. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 733–767. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015240

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 447–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005

- Cacioppo, J. T., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2006). Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging, 21(1), 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140

- Cain, A. E., Depp, C. A., & Jeste, D. V. (2009). Ecological momentary assessment in aging research: A critical review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(11), 987–996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.01.014

- Carstensen, L. L., Turan, B., Scheibe, S., Ram, N., Ersner-Hershfield, H., Samanez-Larkin, G. R., Brooks, K. P., & Nesselroade, J. R. (2011). Emotional experience improves with age: Evidence based on over 10 years of experience sampling. Psychology and Aging, 26(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021285

- Charles, S. T. (2010). Strength and vulnerability integration: A model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 136(6), 1068–1091. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021232

- Chawla, K., Kunonga, T. P., Stow, D., Barker, R., Craig, D., & Hanratty, B. (2021). Prevalence of loneliness amongst older people in high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One, 16(7), e0255088. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255088

- Clark, D. A. (Ed.). (2005). Intrusive thoughts in clinical disorders: Theory, research, and treatment. Guilford Press.

- Compernolle, E. L., Finch, L. E., Hawkley, L. C., & Cagney, K. A. (2022). Home alone together: Differential links between momentary contexts and real-time loneliness among older adults from Chicago during versus before the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Science & Medicine, 299, 114881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114881

- Compernolle, E. L., Finch, L. E., Hawkley, L. C., & Cagney, K. A. (2021). Momentary loneliness among older adults: Contextual differences and their moderation by gender and race/ethnicity. Social Science & Medicine, 285, 114307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114307

- Courtin, E., & Knapp, M. (2017). Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: A scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(3), 799–812. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12311

- Cutright, P., Stack, S., & Fernquist, R. M. (2006). The age structures and marital status differences of married and not married male suicide rates: 12 developed countries. Archives of Suicide Research, 10(4), 365–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811110600791205

- Cutright, P., Stack, S., & Fernquist, R. (2007). Marital status integration, suicide disapproval, and societal integration as explanations of marital status differences in female age-specific suicide rates. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 37(6), 715–724. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2007.37.6.715

- Dahlberg, L., McKee, K. J., Frank, A., & Naseer, M. (2022). A systematic review of longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 26(2), 225–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1876638

- Dejonckheere, E., Demeyer, F., Geusens, B., Piot, M., Tuerlinckx, F., Verdonck, S., & Mestdagh, M. (2022). Assessing the reliability of single-item momentary affective measurements in experience sampling. Psychological Assessment, 34(12), 1138–1154. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0001178

- Fingerman, K. L., Kim, Y. K., Ng, Y. T., Zhang, S., Huo, M., & Birditt, K. S. (2022). Television viewing, physical activity, and loneliness in late life. The Gerontologist, 62(7), 1006–1017. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab120

- Goldman, A. W., & Compernolle, E. L. (2023). Personal network size and social accompaniment: Protective or risk factor for momentary loneliness, and for whom? Society and Mental Health, 13(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/21568693221142336

- Håkansson, K., Rovio, S., Helkala, E. L., Vilska, A. R., Winblad, B., Soininen, H., Nissinen, A., Mohammed, A. H., & Kivipelto, M. (2009). Association between mid-life marital status and cognitive function in later life: Population based cohort study. British Medical Journal, 339, b2462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2462

- Hawkley, L. C., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Masi, C. M., Thisted, R. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2008). From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63(6), 375–384.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Opportunities for the health care system. The National Academies Press.

- Heinrich, L. M., & Gullone, E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(6), 695–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002

- Holt-Lunstad, J., & Smith, T. B. (2016). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for CVD: Implications for evidence-based patient care and scientific inquiry. Heart, 102(13), 987–989. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-309242

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

- Jak, A. J., Bondi, M. W., Delano-Wood, L., Wierenga, C., Corey-Bloom, J., Salmon, D. P., & Delis, D. C. (2009). Quantification of five neuropsychological approaches to defining mild cognitive impairment. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(5), 368–375. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e31819431d5

- Joormann, J., & Quinn, M. E. (2014). Cognitive processes and emotion regulation in depression. Depression and Anxiety, 31(4), 308–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22264

- Kang, J. E., Graham-Engeland, J. E., Scott, S., Smyth, J. M., & Sliwinski, M. J. (2023). The relationship between loneliness and the experiences of everyday stress and stressor-related emotion. Stress and Health, 40(2), e3294. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3294

- Katz, M. J., Wang, C., Nester, C. O., Derby, C. A., Zimmerman, M. E., Lipton, R. B., Sliwinski, M. J., & Rabin, L. A. (2021). T-MoCA: A valid phone screen for cognitive impairment in diverse community samples. Alzheimer’s & Dementia (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 13(1), e12144. https://doi.org/10.1002/dad2.12144

- Kislev, E. (2022). Aging, marital status, and loneliness: Multilevel analyses of 30 countries. Research on Ageing and Social Policy, 10(1), 77–103. https://doi.org/10.17583/rasp.8923

- Knight, M., Seymour, T. L., Gaunt, J. T., Baker, C., Nesmith, K., & Mather, M. (2007). Aging and goal-directed emotional attention: Distraction reverses emotional biases. Emotion, 7(4), 705–714. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.7.4.705

- Kuhl, J., & Baumann, N. (2013). Self-regulation and rumination: Negative affect and impaired self-accessibility. In W. J. Perrig & A. Grob (Eds.), Control of human behavior, mental processes, and consciousness (pp. 259–279). Psychology Press.

- Lara, E., Martín-María, N., De la Torre-Luque, A., Koyanagi, A., Vancampfort, D., Izquierdo, A., & Miret, M. (2019). Does loneliness contribute to mild cognitive impairment and dementia? A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Ageing Research Reviews, 52, 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2019.03.002

- Liu, H., Zhang, Y., Burgard, S. A., & Needham, B. L. (2019). Marital status and cognitive impairment in the United States: Evidence from the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Annals of Epidemiology, 38, 28–34.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.08.007

- Mansueto, G., Marino, C., Palmieri, S., Offredi, A., Sarracino, D., Sassaroli, S., Ruggiero, G. M., Spada, M. M., & Caselli, G. (2022). Difficulties in emotion regulation: The role of repetitive negative thinking and metacognitive beliefs. Journal of Affective Disorders, 308, 473–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.086

- Marchant, N. L., & Howard, R. J. (2015). Cognitive debt and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 44(3), 755–770. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-141515

- Martín-María, N., Caballero, F. F., Lara, E., Domènech-Abella, J., Haro, J. M., Olaya, B., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., & Miret, M. (2021). Effects of transient and chronic loneliness on major depression in older adults: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 36(1), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5397

- McCade, D., Savage, G., & Naismith, S. L. (2011). Review of emotion recognition in mild cognitive impairment. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 32(4), 257–266. https://doi.org/10.1159/000335009

- Molenaar, P. C. (2004). A manifesto on psychology as idiographic science: Bringing the person back into scientific psychology, this time forever. Measurement, 2(4), 201–218.

- Moore, R. C., Kaufmann, C. N., Rooney, A. S., Moore, D. J., Eyler, L. T., Granholm, E., Woods, S. P., Swendsen, J., Heaton, R. K., Scott, J. C., & Depp, C. A. (2017). Feasibility and acceptability of ecological momentary assessment of daily functioning among older adults with HIV. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(8), 829–840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2016.11.019

- Mroczek, D. K., & Almeida, D. M. (2004). The effect of daily stress, personality, and age on daily negative affect. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 355–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00265.x

- Mund, M., Maes, M., Drewke, P. M., Gutzeit, A., Jaki, I., & Qualter, P. (2023). Would the real loneliness please stand up? The validity of loneliness scores and the reliability of single-item scores. Assessment, 30(4), 1226–1248. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911221077227

- Munoz, E., Sliwinski, M. J., Smyth, J. M., Almeida, D. M., & King, H. A. (2013). Intrusive thoughts mediate the association between neuroticism and cognitive function. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(8), 898–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.07.019

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide. Eighth Edition. Muthén & Muthén.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Social Isolation and loneliness in older adults: Opportunities for the health care system. National Academies Press.

- Nicolaisen, M., & Thorsen, K. (2014). Who are lonely? Loneliness in different age groups (18–81 years old), using two measures of loneliness. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 78(3), 229–257. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.78.3.b

- Ong, A. D., Uchino, B. N., & Wethington, E. (2016). Loneliness and health in older adults: A mini-review and synthesis. Gerontology, 62(4), 443–449. https://doi.org/10.1159/000441651

- O’Súilleabháin, P. S., Gallagher, S., & Steptoe, A. (2019). Loneliness, living alone, and all-cause mortality: The role of emotional and social loneliness in the elderly during 19 years of follow-up. Psychosomatic Medicine, 81(6), 521–526. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000710

- Page, R. M., & Cole, G. E. (1991). Demographic predictors of self-reported loneliness in adults. Psychological Reports, 68(3 Pt 1), 939–945. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1991.68.3.939

- Pasymowski, S., Roberto, K. A., & Blieszner, R. (2013). Adjustment to mild cognitive impairment: Perspectives of male care partners and their spouses. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 12(3), 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332691.2013.806703

- Peplau, L. A., & Perlman, D. (1982). Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research, and therapy (vol. 36). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Perissinotto, C. M., Stijacic Cenzer, I., & Covinsky, K. E. (2012). Loneliness in older persons: A predictor of functional decline and death. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(14), 1078–1083. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993

- Pikhartova, J., Bowling, A., & Victor, C. (2016). Is loneliness in later life a self-fulfilling prophecy? Aging & Mental Health, 20(5), 543–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1023767

- Rachman, S. (1981). Part I. Unwanted intrusive cognitions. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 3(3), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6402(81)90007-2

- Roberts, R. O., Knopman, D. S., Mielke, M. M., Cha, R. H., Pankratz, V. S., Christianson, T. J., Geda, Y. E., Boeve, B. F., Ivnik, R. J., Tangalos, E. G., Rocca, W. A., & Petersen, R. C. (2014). Higher risk of progression to dementia in mild cognitive impairment cases who revert to normal. Neurology, 82(4), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000055

- Sarason, I. G., Pierce, G. R., & Sarason, B. R. (Eds.) (2014). Cognitive interference: Theories, methods, and findings. Routledge.

- Smith, K. J., & Victor, C. (2019). Typologies of loneliness, living alone and social isolation, and their associations with physical and mental health. Ageing and Society, 39(8), 1709–1730. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18000132

- Song, J., Howe, E., Oltmanns, J. R., & Fisher, A. J. (2023). Examining the concurrent and predictive validity of single items in ecological momentary assessments. Assessment, 30(5), 1662–1671. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911221113563

- Stawski, R. S., Scott, S. B., Zawadzki, M. J., Sliwinski, M. J., Marcusson-Clavertz, D., Kim, J., Lanza, S. T., Green, P. A., Almeida, D. M., & Smyth, J. M. (2019). Age differences in everyday stressor-related negative affect: A coordinated analysis. Psychology and Aging, 34(1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000309

- Stawski, R. S., Mogle, J., & Sliwinski, M. J. (2011). Intraindividual coupling of daily stressors and cognitive interference in old age. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66B(Supplement 1), i121–i129. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbr012

- Stepler, R. (2016). Living arrangements of older Americans by gender. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2016/02/18/2-living-arrangements-of-older-americans-by-gender/.

- Sundström, A., Adolfsson, A. N., Nordin, M., & Adolfsson, R. (2020). Loneliness increases the risk of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(5), 919–926. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbz139

- Van Bogart, K., Scott, S. B., Harrington, K. D., Felt, J. M., Sliwinski, M. J., & Graham-Engeland, J. E. (2023). Examining the bidirectional nature of loneliness and anxiety among older adults in daily life. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 78(10), 1676–1685. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbad105

- Vohs, K. D., & Baumeister, R. F. (Eds.) (2016). Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. Guilford Publications.

- Yu, J., Lam, C. L. M., & Lee, T. M. C. (2016). Perceived loneliness among older adults with mild cognitive impairment. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(10), 1681–1685. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216000430

- Yu, K., Wild, K., Dowling, N. M., Kaye, J. A., Silbert, L. C., & Dodge, H. H. (2022). Emotional characteristics of socially isolated older adults with MCI using tablet administered NIH toolbox: I-CONECT study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 14(1), e12372. https://doi.org/10.1002/dad2.12372

- Zhaoyang, R., Scott, S. B., Martire, L. M., & Sliwinski, M. J. (2021). Daily social interactions related to daily performance on mobile cognitive tests among older adults. PLOS One, 16(8), e0256583. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256583

- Zhaoyang, R., Sliwinski, M. J., Martire, L. M., & Smyth, J. M. (2018). Age differences in adults’ daily social interactions: An ecological momentary assessment study. Psychology and Aging, 33(4), 607–618. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000242