Abstract

Objectives

This study examined the mediating role of care partner burden on the relationship between patient clinical factors (i.e. cognition, physical function, and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia [BPSD]) and care partner mental health (i.e. anxiety and depression) among dementia care partners at hospital discharge.

Method

The sample consisted of 431 patient and care partner dyads enrolled in the Family centered Function-focused Care (Fam-FFC) study; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03046121. Mediation analyses were conducted to test the role of care partner burden on the associations between patient clinical factors, and care partner anxiety and depression.

Results

Mediation models demonstrated that care partner burden partially mediated the relationship between patient physical function and care partner anxiety and depression, as well as patient BPSD and care partner anxiety and depression.

Conclusion

Findings highlight the need for clinicians and service providers to implement comprehensive strategies that address both patient clinical factors (i.e. physical function and BPSD) and care partner burden, to optimize care partner mental health outcomes during post-hospital transition.

Introduction

Persons living with dementia have two to four times more hospitalizations than those without dementia and represent one-fourth of older adults admitted to hospitals (Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2023; Phelan et al., Citation2012). When hospitalized, care partners caring for persons living with dementia experience increased stress, which stems from worry about the patients’ condition and comfort, and significant disruptions in their established caregiving routines (Abbott et al., Citation2022; Boltz et al., Citation2015). Care partners of persons living with dementia express concerns about their loved ones’ health and the ramifications of hospitalization, such as heightened care needs, which significantly impact their psychological well-being (Abbott et al., Citation2022). In the post-hospital transition phase, family care partners are typically planning to deal with the increased care dependency and medically complex needs of the person living with dementia (Boltz et al., Citation2015; Dramé et al., Citation2012; Gual et al., Citation2018; Mathews et al., Citation2014). Consequently, they experience compounded stress to their psychological well-being, resulting in increased levels of levels burden, anxiety, and depression at hospital discharge (Kuzmik et al., Citation2023).

Prior literature has demonstrated that patient-related factors such as advanced age (Boltz et al., Citation2015), female gender (Resnick et al., Citation2022), increased comorbidities (Zhang et al., Citation2023), poorer cognition (García-Alberca et al., Citation2011; Steinsheim et al., Citation2023), reduced physical function (Boltz et al., Citation2015), and higher behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) (Arthur et al., Citation2018; Putri et al., Citation2022; Steinsheim et al., Citation2023) can influence the development of burden, anxiety, or depression in care partners of persons living with dementia in various settings. Additionally, care partners who are of older age (Liang et al., Citation2016; Steinsheim et al., Citation2023), female gender (Pillemer et al., Citation2018; Putri et al., Citation2022; Watson et al., Citation2019), White race (Kuzmik et al., Citation2023; Liu et al., Citation2020), and reside with the patient (Jang et al., Citation2016) tend to experience higher levels of burden, anxiety, or depression in their caregiving role across diverse environments. However, these studies did not explore the interplay between patient clinical characteristics, care partner burden, and care partner mental health outcomes among dementia care partners at hospital discharge. Understanding the underlying pathways that link patient clinical characteristics to care partner mental health via care partner burden will help guide the development of interventions aimed to enhance the psychological well-being of care partners of persons living with dementia during hospital discharge, which is a critical timepoint in the post-acute care transition.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the mediating role of care partner burden on the relationship between patient clinical factors (i.e. cognition, physical function, BPSD) and care partner mental health (i.e. anxiety and depression) among dementia care partners at hospital discharge. Pearlin et al. (Citation1990) developed a conceptual stress process model for care partners, which incorporates various elements including background and contextual factors as predictors, and stressors as mediators, all examined in relation to care partner outcomes. Our study adapted this framework to explore models that integrate patient clinical factors (i.e. cognition, physical function, BPSD) as predictors of care partner mental health outcomes (i.e. anxiety and depression), with mediation by care partner burden. Utilizing baseline and discharge from a cluster randomized trial of the Family-centered Function-focused Care (Fam-FFC) study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03046121), it was hypothesized that poorer cognition, lower physical function, and higher BPSD would independently predict greater care partner anxiety and depression, with care partner burden mediating these relationships.

Methods

Study design, sample, and setting

The current study is a secondary analysis of the Fam-FFC trial. Fam-FFC is a collaborative model involving both families and nurses with a specific focus on improving outcomes for patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) who are living in the community and undergo hospitalization. This model aims to enhance two primary aspects: 1) the physical and cognitive recovery of hospitalized patients with ADRD during their hospital stay and the 60-day post-acute period, and 2) the preparedness and experiences of family care partners. The efficacy of the Fam-FFC intervention on improving care partner outcomes has been published (Boltz et al., Citation2023). The study protocol received ethical approval from the university Institutional Review Board and has been published (Boltz et al., Citation2018). Prior to data collection, all participants provided written informed consent.

The study sample consisted of 431 patient/care partner dyads who were selected from six medical units spanning three hospitals in Pennsylvania. To be eligible for participation care partners had to meet the following criteria: 1) be aged 18 or older, 2) be fluent in English or Spanish, and 3) have a familial or significant relations with the patient as defined by the patient or legally authorized individuals as the primary care partner responsible for ongoing oversight and support. Care partners were excluded if they were unable to recall at least two words from a three-word recall task.

For patients to qualify for participation, the following criteria need to be met: 1) be aged 65 or older, 2) be proficient in English or Spanish, 3) have been residing in the community before their hospital admission, 4) score ≤ 25 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (Nasreddine et al., Citation2005) and ≥ 2 on the AD8 Dementia Screening Interview (Galvin et al., Citation2006), indicating positive dementia screening, 5) have a diagnosis of very mild to moderate stage dementia with a score of 0.5 to 2.0 on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) (Morris, Citation1997), 6) demonstrate impaired function with a score of ≥ 9 on the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) (Pfeffer et al., Citation1982), and 7) have a family care partner willing to participate throughout the study. Patients were excluded if they were 1) admitted from a nursing home, 2) enrolled in hospice care, 3) did not have a family care partner to participate, or 4) had a significant neurological condition affecting cognition other than dementia or had a major acute psychiatric disorder.

Procedures

Data collection from care partners and patients was conducted by skilled and experienced research evaluators who were blinded to the intervention. Within 48 h of hospital admission, patient demographics, cognition, and co-morbidity data were obtained either by extraction from the electronic health record or patient report. Patient clinical measures and caregiver data were collected by care partner report within a 72-h timeframe following the patient’s hospital discharge.

Measures

Independent variables

Patient variables were cognition, physical function, and BPSD. Cognition was measured using the MoCA test (total scores ranged from 0-25), which examined the patient’s executive functioning, orientation, memory, abstract thinking, and attention (Nasreddine et al., Citation2005). The MoCA has been established as a valid and reliable measure across culturally diverse populations (Bernstein et al., Citation2011). The Cronbach’s alpha of the MoCA in the present sample was 0.76. Physical function was measured using the Barthel Index (BI), a 10-item tool (Mahoney & Barthel, Citation1965). The BI measures an individual’s performance in activities of daily living, specifically pertaining to mobility, self-care, and bowel/bladder functions. Scores on the BI can vary from 0 to 100, with high scores indicating a higher level of functional ability. Previous research has confirmed the reliability and validity of the BI (Mahoney & Barthel, Citation1965; Ranhoff, Citation1997). In the current study, the BI demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.81. To assess BPSD, we used the Brief Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI-Q), which consists of 12 items evaluating neuropsychiatric symptoms (Cummings et al., Citation1994). If BPSD was present, the severity of each item was rated on a three-point scale: 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), and 3 (severe). The total scores can range from 0-36, with higher scores indicating a higher degree of BPSD. The NPI-Q has been well-documented to have good validity and reliability (Cummings et al., Citation1994). The Cronbach’s alpha of the NPI-Q in the current study was 0.77.

Outcome variables

To assess care partner anxiety and depression, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Subscale Anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D) were utilized (Herrmann, Citation1997). Each of these subscales comprises seven questions, with each item being scored on a scale from 0-3. A total score within the range of 0-7 was considered normal, while scores between 8-10 were regarded as borderline abnormal, and scores from 11-21 were indicative of abnormality of each respective subscale. Abnormal scores were indicative of the presence of depression or anxiety. Previous evaluations of the HADS-A and HADS-D have demonstrated strong psychometric properties (Gough & Hudson, Citation2009). In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha values were α = 0.84 for HADS-A and α = 0.80 for HADS-D.

Mediator variable

Care partner burden was assessed by the Short-Form Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-12), a 12-item instrument designed to evaluate distinct domains: personal strain and role strain (Ballesteros et al., Citation2012). Responses to the items were scored on a scale from 0 (indicating ‘never’) to 4 (representing ‘almost always’). The total scores could range from 0 to 48, with higher scores reflecting increased levels of care partner burden. Previous studies have demonstrated the tool’s internal consistency and concurrent validity (Lin et al., Citation2017). The Cronbach’s alpha of the ZBI-12 in the present sample was 0.90.

Covariate variables

Covariates included effects of the intervention, patient characteristics (i.e. age, gender, and comorbidities) (Boltz et al., Citation2015; García-Alberca et al., Citation2011; Resnick et al., Citation2022; Steinsheim et al., Citation2023; Zhang et al., Citation2023), and care partner characteristics (age, gender, race, and cohabitation with patient) (Jang et al., Citation2016; Kuzmik et al., Citation2023; Liang et al., Citation2016; Liu et al., Citation2020; Pillemer et al., Citation2018; Putri et al., Citation2022; Steinsheim et al., Citation2023; Watson et al., Citation2019). Patient’s age, gender, and comorbidities were obtained through chart extraction. Comorbidities were assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), a comprehensive summary of the total count of comorbidities (van Doorn et al., Citation2001). Care partner’s gender, age, race, and cohabitation with patient were obtained via care partner self-report.

Data analysis

All data analyses were completed using SPSS and AMOS software version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics, including means and proportions, were used to portray the characteristics of both care partner and patients. Correlations between study variables were examined by Pearson’s correlation analysis. Variables that did not show significant correlations with either the independent variable (patient cognition, physical function, or BPSD) or the dependent variable (care partner anxiety or depression) were excluded from the mediation analyses. Multicollinearity was identified when variables demonstrated high correlations (r > 0.9).

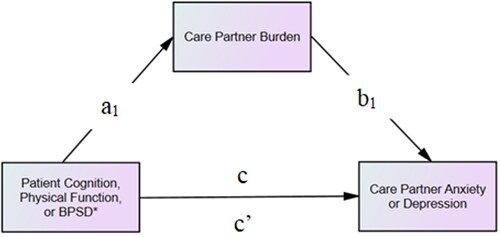

We utilized a nonparametric bootstrapping approach with 5,000 samples to examine whether care partner burden mediates the relationship between patient clinical characteristics (i.e. cognition, physical function, and BPSD) and care partner mental health (i.e. anxiety and depression). Six mediation models were conducted, with unstandardized path coefficients (a, b, c, and c’) determined for each model (). Specifically, we assessed the direct effect (c’ path) of the independent variable on the dependent variable and the specific indirect effects (ab) of the independent variable on the dependent variable through the mediator. Path-a indicated the influence of the independent variable on the mediator, while path-b represented the influence of the mediator on the dependent variable. Additionally, the total effect (c-path) of the independent variable on the dependent was determined, which combines both direct and specific indirect effects. Mediation was confirmed with a significant indirect effect, indicated by a 95% bias-corrected confidence interval that excluded zero. Covariates for all models included the effects of the intervention, patient characteristics (i.e. age, gender, and comorbidities), and care partner characteristics (age, gender, race, and cohabitation with patient). For all analyses, the statistical significance threshold was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Figure 1. Hypothesized model of the mediating role of care partner burden between patient clinical characteristics (cognition, physical function, and BPSD) and care partner mental health (anxiety and depression). Note. *Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia. a-path represents the direct effects from patient clinical factors to the mediator, b-path indicates the direct effects from the mediator to care partner mental health outcomes, c-path signifies the total effect from patient clinical factors to care partner mental health outcomes without considering the mediator, and c’-path represents the direct effect from patient clinical characterizes to care partner mental health outcomes after accounting for the mediator.

Results

displays the characteristics of 431 care partners and patients who participated in the Fam-FFC study. The care partners had a mean age of 61.7 (SD = 14.2) years, and majority identified as female (72.9%) and White (64.7%), with 34% African American. More than half of the care partners were married (60.3%), had more than high school education (65.4%), and lived with the patient (59.9%). Among the care partners, 51.5% were the son or daughter of the patient. Care partners who were employed outside of the home worked an average of 40.2 (SD = 14.2) hours per week. Additionally, care partners reported low anxiety levels with a mean HADS-A score of 5.3 (SD = 4.7), low depression levels based on a mean HADS-D score of 3.5 (SD = 3.8), and low burden with a mean ZBI-12 score of 9.8 (SD = 9.4).

Table 1. Characteristics of study participants (N = 431).

Among the patients, 58.2% identified as female and 64.3% identified as White. The patients had an average age of 81.5 (SD = 8.4) years, 4.33 (SD = 2.8) comorbidities, and moderate cognitive impairment based on the MoCA (mean score of 11.8, SD = 7.0). The patients had a mean length of hospital stay of 6.5 (SD = 4.5) days. Most of the patients were widowed/divorced/separated (54.8%) and high school graduates (40.4%). The patients had had some BPSD (mean NPI-Q score of 6.35, SD = 5.9) and demonstrated moderate functional impairment (mean BI score of 68.14, SD = 27.3). The reasons for hospital admission in the sample varied, with infections accounting for the highest percentage (19.7%), followed by altered mental status (11.4%), and pain (10.7%).

The correlations between study variables are displayed in . None of the correlation coefficients among the main variables exceeded the threshold of 0.9, indicating that all variables satisfied the assumptions of multicollinearity. Care partner burden (i.e. potential mediator) showed significant associations with all patient characteristics, as well as both care partner anxiety and care partner depression. Thus, care partner burden was included as a potential mediator in each subsequent mediation analyses.

Table 2. Results Of pearson correlation analysis.

The results of the mediation analysis are presented in . For the outcome care partner anxiety (Models 1-3), each model had statistically significant total effects for all patient clinical characteristics: for cognition B = −0.112, p < 0.001; for physical function B = −0.030, p = 0.002; for BPSD B = −0.296, p < .001. Only the direct effect for cognition was not significant (B = −0.029, p = 0.257). The direct effects for physical function and BPSD remained significant but with smaller magnitudes (B = −0.013, p = 0.041 and B = 0.110, p = 0.009, respectively). Furthermore, significant effects of patient cognition (B = −0.264, p = <0.001), physical function (B = −0.056, p = <0.001), and BPSD (B = 0.640, p = <0.001) on care partner burden were observed in each model, along with the effects of care partner burden on anxiety for each respective model (Model 1, B = 0.314, p = <0.001; Model 2, B = 0.312, p = <0.001; Model 3, B = 0.290, p = <0.001). Additionally, significant indirect effects were found for care partner burden on patient physical function and care partner anxiety (B = −0.017; 95% CI = −0.028, −0.008), as well as on patient BPSD and care partner anxiety (B = 0.186; 95% CI = 0.138, 0.239). However, the indirect effect of care partner burden on patient cognition and care partner anxiety was not significant (B = −0.083; 95% CI = −0.124, 0.042). Thus, care partner burden partially mediated the relationship between physical function and care partner anxiety, as well as the relationship between patient BPSD and care partner anxiety.

Table 3. Mediation effects of patient clinical characteristics on care partner mental health through care partner burden.

Similarly, for care partner depression (Models 4-6), each model had statistically significant total effects for all patient clinical characteristics: for cognition B = −0.097, p < 0.001, for physical function B = −0.034, p = 0.002, for BPSD B = 0.203, p < .001. Only the direct effect for cognition was not significant (B = −0.035, p = 0.092). The direct effects for physical function and BPSD remained significant but with smaller magnitudes (B = −0.021, p = 0.011 and B = 0.059, p = 0.024, respectively). Likewise, significant effects of patient cognition (B = −0.264, p = <0.001), physical function (B = −0.056, p = <0.001), and BPSD (B = 0.640, p = <0.001) on care partner burden were observed in each model, along with the effects of care partner burden on depression for each respective model (Model 4, B = 0.234, p = <0.001; Model 5, B = 0.229, p = <0.001; Model 6, B = 0.224, p = <0.001). Furthermore, significant indirect effects were found for care partner burden on patient physical function and care partner depression (B = −0.013; 95% CI = −0.021, −0.006), as well as on patient BPSD and care partner depression (B = 0.224; 95% CI = 0.187, 0.265). However, the indirect effect of care partner burden on patient cognition and care partner depression was not significant (B = −0.062; 95% CI = −0.094, 0.032). Thus, care partner burden partially mediated the relationship between physical function and care partner depression, as well as the relationship between patient BPSD and care partner depression.

Discussion

Guided by the Stress Process Model for Caregiving (Pearlin et al., Citation1990), the present study examined the mediating role of care partner burden on the relationship between patient clinical factors (i.e. cognition, physical function, and BPSD) and care partner mental health (i.e. anxiety and depression) among care partners of persons living with dementia at hospital discharge. The results partially supported our hypothesis, indicating that lower patient physical function was predictive of increased care partner anxiety and depression, with these relationships partially mediated by care partner burden. Likewise, greater patient BPSD was predictive of increased care partner anxiety and depression, also partially mediated by care partner burden. However, care partner burden did not mediate the relationship between patient cognition and either care partner anxiety or depression. Our findings underscore the importance of considering patient clinical factors (i.e. physical function and BPSD), and care partner burden as related predictive factors when assessing care partner anxiety and depression at hospital discharge. Interventions should target both patient clinical factors (i.e. physical function and BPSD) and care partner burden to enhance care partner mental health outcomes at hospital discharge.

Results corroborate previous research that highlighted the influence of patient factors, including reduced physical function and increased BPSD, in contributing to heightened levels of burden, anxiety, and depression experienced by care partners of older adults residing in diverse community environments (Arthur et al., Citation2018; Boltz et al., Citation2015; Putri et al., Citation2022; Steinsheim et al., Citation2023). Our study adds to literature by examining the underlying pathways that link patient clinical characteristics to care partner mental health via care partner burden at hospital discharge. The recognition of care partner burden as mediator between patient physical function and care partner anxiety and depression, as well as BPSD and care partner anxiety and depression, highlights the importance of developing tailored interventions and strategies to enhance care partner well-being during hospital discharge. Future research should investigate whether our findings can be generalized to a broader population of care partners spanning various cultures and demographics.

Differing from prior work (García-Alberca et al., Citation2011; Steinsheim et al., Citation2023), this study did not identify care partner burden as a mediator in the relationship between patient cognition and care partner anxiety or depression. The divergent findings may suggest that the results are contingent on the specific characteristics of the sample. Since our sample displayed relatively low levels of care partner burden, anxiety, and depression, it is possible that the low levels of patient cognition made it difficult to detect an association. In addition, our sample consisted of patients with only mild to moderate dementia, potentially suggesting that more severe dementia could be linked to poorer mental health among care partners during post-hospital transition. Therefore, future research should involve a more comprehensive examination of the interplay between patient clinical factors, care partner burden, and depression among dementia caregivers at the time of hospital discharge.

Clinical implications of the findings emphasize the critical role of integrating patient clinical factors, including physical function and BPSD, and care partner burden into the assessment and management of care partners’ psychological well-being during hospital discharge transitions. Prioritizing assessment of these factors upon discharge enables healthcare providers (i.e. clinicians and service providers) to develop customized care plans and support strategies tailored to the unique needs of both patients and care partners. This proactive approach aims to mitigate care partner burden and improve mental health outcomes during the critical post-hospital transition period. Additionally, by recognizing the significant impact of patient clinical factors on care partner mental health, healthcare providers can better advocate for comprehensive support services and resources to assist care partners in managing the challenges they face at hospital discharge. Incorporating these findings into clinical practice has the potential to improve the well-being of both patients and their care partners during hospital discharge.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that it is one of only a few studies that reports on the mediating role between patient clinical characteristics and care partner mental health among dementia care partners at hospital discharge, a critical timepoint that has been underexplored within the vulnerable population of care partners for persons living with dementia. The study also included a large cohort of care partners and patients living with dementia.

This research has some limitations to consider. First, in this secondary analysis of cross-sectional data, it is not feasible to establish causal relationships between patient clinical factors, care partner burden, and care partner mental health outcomes. In addition, the use of self-reported data in the data collection process may have included biases linked to both social desirability and memory-related concerns. Further, due to our reliance on data from a parent study, this study did not include variables such as the extent of the care partner’s involvement during hospitalization and the patient’s diagnoses and prognosis at discharge. We were also unable to investigate additional factors that may influence care partners’ anxiety and depression such as socioeconomic status, duration of caregiving, aspects of the living environment (e.g. issues like inadequate space), and patients’ medication complexity. Lastly, the generalizability of our findings to a larger population is limited, as our study was restricted to three hospitals within a single state and included a limited representation of racial and ethnic groups.

Conclusion

In the present study, we found that care partner burden partially mediated the relationship between patient physical function and care partner anxiety and depression, as well as patient BPSD and care partner anxiety and depression. Based on our findings, it is recommended that clinicians and service providers implement comprehensive strategies that address both patient clinical factors (i.e. physical function and BPSD) and care partner burden, to enhance care partner mental health outcomes. Tailored interventions, including individual adapted physical activity, management of BPSD, and education for care partners, are essential to effectively mitigate anxiety and depression among care partners during the post-hospital transition. Future research would benefit from a longitudinal analysis of the mediating role of care partner burden on the relationship between patient clinical factors and care partner mental health after hospitalization. Utilizing this longitudinal approach would facilitate a deeper understanding of the changes and challenges in the psychological well-being of care partners over the post-hospitalization period.

Ethical approval

This study received ethical approval from the university Institutional Review Board. All study participants provided written informed consent.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbott, R. A., Rogers, M., Lourida, I., Green, C., Ball, S., Hemsley, A., Cheeseman, D., Clare, L., Moore, D., Hussey, C., Coxon, G., Llewellyn, D. J., Naldrett, T., & Thompson Coon, J. (2022). New horizons for caring for people with dementia in hospital: The DEMENTIA CARE pointers for service change. Age and Ageing, 51(9), afac190. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac190

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2023).). 2023 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures

- Arthur, P. B., Gitlin, L. N., Kairalla, J. A., & Mann, W. C. (2018). Relationship between the number of behavioral symptoms in dementia and caregiver distress: What is the tipping point? International Psychogeriatrics, 30(8), 1099–1107. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104161021700237X

- Ballesteros, J., Santos, B., González-Fraile, E., Muñoz-Hermoso, P., Domínguez-Panchón, A. I., & Martín-Carrasco, M. (2012). Unidimensional 12-item Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview for the assessment of dementia caregivers’ burden obtained by item response theory. Value in Health: The Journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 15(8), 1141–1147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2012.07.005

- Bernstein, I. H., Lacritz, L., Barlow, C. E., Weiner, M. F., & DeFina, L. F. (2011). Psychometric evaluation of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in three diverse samples. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 25(1), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2010.533196

- Boltz, M., Chippendale, T., Resnick, B., & Galvin, J. E. (2015). Anxiety in family caregivers of hospitalized persons with dementia: Contributing factors and responses. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 29(3), 236–241. https://doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0000000000000072

- Boltz, M., Kuzmik, A., Resnick, B., Trotta, R., Mogle, J., BeLue, R., Leslie, D., & Galvin, J. E. (2018). Reducing disability via a family centered intervention for acutely ill persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: Protocol of a cluster-randomized controlled trial (Fam-FFC study). Trials, 19(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2875-1

- Boltz, M., Mogle, J., Kuzmik, A., BeLue, R., Leslie, D., Galvin, J. E., & Resnick, B. (2023). Testing an intervention to improve post-hospital outcomes in persons living with dementia and their family care partners. Innovation in Aging, 7(7), igad083. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igad083

- Cummings, J. L., Mega, M., Gray, K., Rosenberg-Thompson, S., Carusi, D. A., & Gornbein, J. (1994). The neuropsychiatric inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology, 44(12), 2308–2314. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308

- Dramé, M., Lang, P.-O., Jolly, D., Narbey, D., Mahmoudi, R., Lanièce, I., Somme, D., Gauvain, J.-B., Heitz, D., Voisin, T., de Wazières, B., Gonthier, R., Ankri, J., Saint-Jean, O., Jeandel, C., Couturier, P., Blanchard, F., & Novella, J.-L. (2012). Nursing home admission in elderly subjects with dementia: Predictive factors and future challenges. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 13(1), 83.e17-20–83.e20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2011.03.002

- Galvin, J. E., Roe, C. M., Xiong, C., & Morris, J. C. (2006). Validity and reliability of the AD8 informant interview in dementia. Neurology, 67(11), 1942–1948. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000247042.15547.eb

- García-Alberca, J. M., Lara, J. P., & Berthier, M. L. (2011). Anxiety and depression in caregivers are associated with patient and caregiver characteristics in Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 41(1), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.2190/PM.41.1.f

- Gough, K., & Hudson, P. (2009). Psychometric properties of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in family caregivers of palliative care patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 37(5), 797–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.012

- Gual, N., Morandi, A., Pérez, L. M., Brítez, L., Burbano, P., Man, F., & Inzitari, M. (2018). Risk factors and outcomes of delirium in older patients admitted to postacute care with and without dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 45(1-2), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1159/000485794

- Herrmann, C. (1997). International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale—A review of validation data and clinical results. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 42(1), 17–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00216-4

- Jang, S.-I., Bae, H.-C., Shin, J., Jang, S., Hong, S., Han, K.-T., & Park, E.-C. (2016). Depression in the family of patients with dementia in Korea. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, ®31(6), 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317515628048

- Kuzmik, A., Boltz, M., BeLue, R., Resnick, B., Scott, J., Mogle, J., Leslie, D., & Galvin, J. E. (2023). The Modified caregiver strain index in black and white dementia caregivers at hospital discharge. Clinical Gerontologist, 46(4), 574–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2022.2106927

- Liang, X., Guo, Q., Luo, J., Li, F., Ding, D., Zhao, Q., & Hong, Z. (2016). Anxiety and depression symptoms among caregivers of care-recipients with subjective cognitive decline and cognitive impairment. BMC Neurology, 16(1), 191. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-016-0712-2

- Lin, C.-Y., Wang, J.-D., Pai, M.-C., & Ku, L.-J. E. (2017). Measuring burden in dementia caregivers: Confirmatory factor analysis for short forms of the Zarit Burden Interview. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 68, 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2016.08.005

- Liu, C., Badana, A. N. S., Burgdorf, J., Fabius, C. D., Roth, D. L., & Haley, W. E. (2020). Systematic review and meta-analysis of racial and ethnic differences in dementia caregivers’ well-being. The Gerontologist, 61(5), e228–e243. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa028

- Mahoney, F. I., & Barthel, D. W. (1965). Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Maryland State Medical Journal, 14, 61–65.

- Mathews, S. B., Arnold, S. E., & Epperson, C. N. (2014). Hospitalization and cognitive decline: can the nature of the relationship be deciphered? The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(5), 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2012.08.012

- Morris, J. C. (1997). Clinical dementia rating: A reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. International Psychogeriatrics, 9(S1), 173–176; discussion 177178 https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610297004870

- Nasreddine, Z. S., Phillips, N. A., Bédirian, V., Charbonneau, S., Whitehead, V., Collin, I., Cummings, J. L., & Chertkow, H. (2005). The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(4), 695–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

- Pearlin, L. I., Mullan, J. T., Semple, S. J., & Skaff, M. M. (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30(5), 583–594. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/30.5.583

- Pfeffer, R. I., Kurosaki, T. T., Harrah, C. H., Chance, J. M., & Filos, S. (1982). Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. Journal of Gerontology, 37(3), 323–329. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/37.3.323

- Phelan, E. A., Borson, S., Grothaus, L., Balch, S., & Larson, E. B. (2012). Association of incident dementia with hospitalizations. JAMA, 307(2), 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1964

- Pillemer, S., Davis, J., & Tremont, G. (2018). Gender effects on components of burden and depression among dementia caregivers. Aging & Mental Health, 22(9), 1156–1161. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1337718

- Putri, Y. S. E., Putra, I. G. N. E., Falahaini, A., & Wardani, I. Y. (2022). Factors associated with caregiver burden in caregivers of older patients with dementia in Indonesia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12437. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912437

- Ranhoff, A. H. (1997). Reliability of nursing assistants’ observations of functioning and clinical symptoms and signs. Aging (Milan, Italy), 9(5), 378–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03339617

- Resnick, B., Galik, E., McPherson, R., Boltz, M., Van Haitsma, K., & Kolanowski, A. (2022). Gender differences in disease, function and behavioral symptoms in nursing home residents with dementia. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 44(9), 812–821. https://doi.org/10.1177/01939459211018822

- Steinsheim, G., Malmedal, W., Follestad, T., Olsen, B., & Saga, S. (2023). Factors associated with subjective burden among informal caregivers of home-dwelling people with dementia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 23(1), 644. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04358-3

- van Doorn, C., Bogardus, S. T., Williams, C. S., Concato, J., Towle, V. R., & Inouye, S. K. (2001). Risk adjustment for older hospitalized persons: A comparison of two methods of data collection for the Charlson index. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(7), 694–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00367-x

- Watson, B., Tatangelo, G., & McCabe, M. (2019). Depression and anxiety among partner and offspring carers of people with dementia: a systematic review. The Gerontologist, 59(5), e597–e610. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny049

- Zhang, J., Wang, J., Liu, H., & Wu, C. (2023). Association of dementia comorbidities with caregivers’ physical, psychological, social, and financial burden. BMC Geriatrics, 23(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03774-9