Abstract

Objectives

Perceived expectations for active aging (PEAA) reflect subjective exposure to social expectations about staying active and fit in old age, for example, by maintaining health and social engagement. We investigated whether motivational and personality factors were related to PEAA in the domains of physical health, mental health, and social engagement.

Method

We used a nationally representative sample of German adults (SOEP-IS) covering the entire adult life span (N = 2,007, age range 16–94 years) to test our pre-registered hypotheses.

Results

Multiple regression analyses indicated that motivation (i.e. life goals and health-related worries) was consistently associated with PEAA in the matching domains and mediated the effects of openness to experience on PEAA. No other personality trait was associated with PEAA.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that individuals preferentially notice the expectations for active aging whose content relates to their personal concerns and goals.

Introduction

Many European countries have started implementing active aging strategies to address the pervasive societal effects of demographic aging (World Health Organization, Citation2002), and social expectations for a healthy and active lifestyle in old age have grown (de Paula Couto & Rothermund, Citation2022; Kessler & Warner, Citation2023; Lessenich, Citation2015). However, as theorizing and research on the individual consequences of social change suggest, changing social expectations do not affect individuals directly and are not equally noticeable for everyone (Elder, Citation1974; Pinquart & Silbereisen, Citation2004). As the meaning of active aging is subjective (Bowling, Citation2008), individuals may perceive the corresponding social expectations if they align with their mindsets and predispositions (cf. Fleck et al., Citation2023). Understanding individual differences in perceived expectations for active aging (PEAA; Pavlova et al., Citation2023) can be a first step towards finding out which older adults are influenced by the active aging discourse and in which way. In this study, we investigated whether motivational constructs relating to the personal concerns (Klinger, Citation1996) of individuals and personality traits would be linked to PEAA in the domains of physical health, mental health, and social engagement. To this end, we conducted a correlational study based on a nationally representative sample of German adults (aged 16–94 years).

What are PEAA and which factors contribute to them?

Prescriptive views on aging are beliefs about how older adults should behave, which include social and personal age-based expectations (de Paula Couto & Rothermund, Citation2022). In their seminal work, North and Fiske (Citation2013) identified several domains of prescriptive social expectations directed at older adults, which mostly concern altruistic disengagement from high-status roles and privileges in favor of younger generations. By contrast, social expectations stemming from the active aging paradigm (World Health Organization, Citation2002) emphasize continuing engagement and proactive health maintenance in old age. Although endorsement of both altruistic-disengagement and active-aging prescriptions was related to the belief that older adults should not become a burden, only the latter had positive associations with psychological adjustment in older adults (de Paula Couto et al., Citation2022; Pavlova & Silbereisen, Citation2016).

Most research investigated prescriptive views on aging from the perspective of individuals who hold them, including older adults themselves (e.g. ‘Older adults should stay mentally sharp’; de Paula Couto et al., Citation2022). However, according to the literature on social change, capturing the targets’ perceptions of social expectations is central to understanding what individuals make of the active aging discourse and how it might influence their development (Pinquart & Silbereisen, Citation2004). If prescriptive views on aging have been perceived and endorsed by their targets, such views can serve as personal guidelines for aging well (de Paula Couto & Rothermund, Citation2022; Pinquart & Silbereisen, Citation2004). The concept of PEAA indicates subjective exposure to the corresponding expectations aimed at people personally and perceptibly in everyday life contexts (e.g. ‘It is expected of me to keep myself physically fit’; Pavlova et al., Citation2023). In contrast to the meta-perceptions of age stereotypes (i.e. descriptive beliefs about how older people are generally perceived in a given society; Fasel et al., Citation2021), PEAA are prescriptive and personalized.

Similarly to other descriptive and prescriptive views on aging (Kornadt & Rothermund, Citation2011; Wirth et al., Citation2023), PEAA may also be domain specific. A domain-specific approach aligns with the principles of multidimensionality and contextual embeddedness of lifespan development (Baltes, Citation1987). Differentiated across life domains, such as health or family, views on aging capture both age-related gains and losses, allowing for more accurate predictions of developmental outcomes (Baltes, Citation1987; Kornadt & Rothermund, Citation2015). Concerning PEAA, Pavlova and Silbereisen (Citation2016) found domain-specific effects of certain predictors (e.g. being a volunteer predicted a stronger perceived growth in expectations to contribute to the common good) in a longitudinal study of young-old adults. Building on these findings, Pavlova et al. (Citation2023) investigated PEAA across adulthood. They examined the domains of physical health, mental health, and social engagement, which are in the focus of active aging strategies (Foster & Walker, Citation2015). Perhaps surprisingly, objective factors strongly implicated in active aging, such as socio-structural, socioeconomic, and health differences (World Health Organization, Citation2002), were only weakly or not at all related to PEAA (Pavlova et al., Citation2023; Pavlova & Silbereisen, Citation2012). While self-reported health and subjective socioeconomic status were positively related to PEAA across domains and age groups, cohabiting with a partner was associated with higher PEAA only in older adults (Pavlova et al., Citation2023; cf. Pavlova & Silbereisen, Citation2012). The effects of other commonly considered resources, such as employment, occupational prestige, and church attendance, varied across age groups and domains (Pavlova et al., Citation2023). There were few sex differences, but older age consistently predicted declining perceptions of expectations for active aging (Pavlova & Silbereisen, Citation2016). Nevertheless, individuals of all ages did perceive such expectations, although comparatively less so for social engagement than for physical and mental health (Pavlova et al., Citation2023; Pavlova & Silbereisen, Citation2012).

Given the widespread awareness of the expectations for active aging and the limited role of objective indicators, it is possible that PEAA depend on other, more subjective factors. Indeed, subjective socioeconomic status and general self-reported health (Pavlova et al., Citation2023) or perceived physical and cognitive fitness (Pavlova & Silbereisen, Citation2012) were more strongly related to PEAA than their objective counterparts were. It is known that the meaning of active aging for older adults is highly subjective (Bowling, Citation2008). Thus, it stands to reason that individuals process social expectations for active aging against the backdrop of their mindsets and predispositions (cf. Fleck et al., Citation2023).

Potential contributions of motivation and personality to domain-specific PEAA

In the present study, we focused on the motivational constructs capturing personal concerns of individuals and on the personality traits that are known to promote active aging. We reasoned that the same factors may prepare individuals to perceive the corresponding social expectations. Motivation has a central place in aging well as it guides intentional self-development via future-self projections, which include both desired and feared scenarios (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, Citation2002; Fleck et al., Citation2023; Heckhausen et al., Citation2019). Intrinsic life goals, focused on basic psychological needs or inherent growth (such as self-development or community engagement; Ryan et al., Citation2008), have been associated with physical activity and psychological well-being in later life (Behzadnia et al., Citation2020). Health-related worries are repetitive mental representations of and emotional responses to health-related risks or perceived threats (Brosschot, Citation2002), which may pertain to health in general or to specific physical and mental health conditions, such as dementia (Kessler et al., Citation2012). When perceived as controllable, such worries can facilitate health-preserving behaviors and preparation for old age (Kessler et al., Citation2012; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984).

Motivational factors may facilitate PEAA in several ways. First, life goals and health-related worries may attune one’s cognitive system to expectations for active aging in matching domains. This process is regarded as assimilation in the dual-process framework (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, Citation2002; Klinger, Citation1996): To facilitate investing resources in the goal pursuit, the cognitive system becomes automatically biased toward the content compatible with one’s goals. For instance, individuals who worry about their health or endorse the life goal of self-fulfillment might be more attentive to awareness campaigns or educational programs focused on physical and mental health. Second, as individuals pursue their intrinsic life goals or, driven by health-related worries, try to avoid detrimental health outcomes, they may be attracted to the environments that foster active aging (e.g. volunteering or sports associations) and communicate the corresponding expectations.

Furthermore, many personality traits contribute to health and social engagement in old age (Baek et al., Citation2016; Pocnet et al., Citation2021). In the present study, we considered dispositional optimism and three Big Five traits (McCrae & Costa, Citation2003): openness to experience, conscientiousness, and extraversionFootnote1. Dispositional optimism represents the tendency to hold generalized positive expectations about the future (Carver et al., Citation2010). More optimistic individuals were found to have more positive self-perceptions of aging (Turner & Hooker, Citation2022). Aligned with positive views on aging and, therefore, with an optimistic mindset, expectations for active aging might be more easily perceived by more optimistic individuals. Additionally, more optimistic individuals tend to engage in health-preserving behaviors (Carver et al., Citation2010) and may be confronted with higher expectations for active aging through partaking in the corresponding activities.

Openness to experience is a trait encompassing curiosity, broad-mindedness, artistic interests, preference for variety, and engagement in cognitively enriching activities (McCrae & Costa, Citation2003). Open individuals may actively seek diverse activities while being generally receptive to new information—even if dissimilar to their views (Jackson et al., Citation2020; Price et al., Citation2015). Beyond the findings on the positive associations between openness and cognitive functioning in old age (Baek et al., Citation2016), research on exploration, a conceptually similar trait (Kashdan et al., Citation2004), linked it to perceiving more learning and lifestyle opportunities in times of social change (Lechner et al., Citation2017). Thus, openness to experience may enhance individuals’ receptiveness to new social expectations. Further, conscientiousness represents the tendency to be responsible, diligent, and rule-abiding (McCrae & Costa, Citation2003). Conscientious individuals reportedly have better physical and mental health in old age, presumably due to the cultivation of prudent health behaviors (Baek et al., Citation2016). In terms of content, expectations for active aging may resonate with conscientious individuals’ attention to health maintenance, while their normativity may speak to these individuals’ sense of obligation. Lastly, extraversion represents the tendency to be outgoing and active (McCrae & Costa, Citation2003). Among the Big Five traits, extraversion was most consistently associated with various forms of social engagement such as volunteering (Ackermann, Citation2019). Because of their gregariousness and extensive social networks, extraverts receive more requests to take part in such activities than introverts do (Pollet et al., Citation2011). Hence, extraversion may predispose individuals to perceive expectations for active aging in the social engagement domain in particular.

The present study

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the roles of motivation and personality in perceiving domain-specific expectations for active aging. We used data from the Innovation Sample of the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP-IS), a nationally representative survey. We preregistered our hypotheses on the OSF platform (H1-H6, https://osf.io/24pw8).

Hypotheses regarding motivation reflected the theoretical assumption that matching personal goals and concerns would make individuals more open toward expectations for active aging (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, Citation2002). Since health worry and dementia worry may, at least in part, reflect real health problems, we controlled for self-reported general health. Assuming the same level of general health, we expected a positive relationship between health worry and PEAA in the physical health domain (Hypothesis 1a) and between dementia worry and PEAA in the mental health domain (Hypothesis 1b).Footnote2 Furthermore, we expected the life goal of self-fulfillment to be positively related to PEAA in both health domains (Hypothesis 2a) since health and self-fulfillment may depend on each other (Ryff & Singer, Citation2008), and the life goal of civic engagement to be positively related to PEAA in the social engagement domain (Hypothesis 2b).

We expected dispositional optimism to be positively related to PEAA across domains (Hypothesis 3). With respect to openness to experience, we expected a positive association with PEAA across domains, but especially in the mental health domain (Hypothesis 4), because of the particular connection between openness and cognitive functioning in old age (Baek et al., Citation2016). Next, we hypothesized a unique positive effect of extraversion on PEAA in the social engagement domain (Hypothesis 5). We explored the role of individual conscientiousness in PEAA without formulating directional hypothesesFootnote3. Lastly, we explored age differences in the effects of motivational and personality predictors without hypotheses, because evidence from prior research on related constructs was inconclusive. On the one hand, compared to younger adults, older adults tend to worry less and value personal relationships more (Basevitz et al., Citation2008; Buchinger et al., Citation2022), whereas younger adults have comparatively more development- and status-related goals (Buchinger et al., Citation2022). On the other hand, health is more salient to and health worry more pronounced in older adults (Hunt et al., Citation2003). Besides, life goals related to self-fulfillment and civic engagement are not specific to any life-course stage (Heckhausen et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, although personality traits can change over time (Specht et al., Citation2011), there is no plausible reason to expect differential relationships between personality traits and PEAA across age groups.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

We used cross-sectional and longitudinal data from the SOEP-IS, a yearly multi-disciplinary representative survey of German adults (age 16+). Compared to the standard SOEP questionnaire, the core SOEP-IS questionnaire is shorter, to be complemented by user-designed surveys and experimental modules that answer specific research questions (Socio-Economic Panel, Citation2018). Our items on PEAA, preparation for age-related changes, and age stereotypes (Pavlova et al., Citation2023) constituted the module ‘Ageing in a Changing Society’ in the 2016 SOEP-IS wave and were administered to the randomly drawn subsample of 2,007 individuals aged 16–94 that we used in the present study. Thus, our analyses were based on both primary and secondary data, as we capitalized on the large number of variables available from this and previous SOEP-IS measurements. presents the descriptive statistics.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

For the SOEP-IS survey, trained interviewers select households using a random-walk algorithm and conduct standardized computer-assisted personal interviews. Participants receive monetary incentives (Socio-Economic Panel, Citation2024). According to the fieldwork report (Zweck & Glemser, Citation2018), in 2016, 3,049 out of the 3,550 households that were approached participated (85.9%); at the individual level, 4,802 of the 5,376 eligible participated (89.3%), and the interviews lasted 92.7 min on average.

Measures

Perceived expectations for active aging (PEAA)

To assess PEAA, we employed three single items adapted from the Jena Study on Social Change and Human Development (Pavlova & Silbereisen, Citation2012) with the instruction ‘In the following, we want to ask you about aging and social expectations. Please think of your everyday life. In our society, we often face certain expectations of other people. The following questions relate to these expectations’. Each item had a 7-point rating scale (1 = does not apply at all; 7 = applies completely) and referred to a specific domain, either physical health (‘It is expected of me to keep myself physically fit’), mental health (‘It is expected of me to keep myself mentally fit’), or social engagement (‘People have high expectations that I get involved in social and non-profit-making activities’). Their psychometric properties suggested that these domains could be used separately to measure specific PEAA domains (Pavlova et al., Citation2023).

Motivational predictors

Regarding health-related worries, we assessed general health worry and dementia worry (Brosschot, Citation2002: Kessler et al., Citation2012). For health worry, we employed a single item from a set of questions about various concerns (‘How concerned are you about the following issues? … your health’, 1 = not concerned at all, 3 = very concerned; previously used by Bauer et al., Citation2020) administered in 2015. We assessed dementia worry with a single item administered in 2012 (‘How concerned are you about getting a form of dementia such as Alzheimer’s one day?’ 1 = not at all, 4 = severely; Hajek & König, Citation2020). We also used two single items from a set of questions about the importance of life goals administered in 2016 (previously used by Buchinger et al., Citation2022), ‘Various things can be important for various people. Are the following things currently important for you? … be politically and/or socially involved; be self-fulfilled’ (1 = quite unimportant, 4 = very important).

Personality predictors

We used the items on extraversion, openness to experience, and conscientiousness from the Big Five section of the SOEP administered in 2015 (Gerlitz & Schupp, Citation2005). Three items referred to extraversion (‘I am someone who … is reserved’ coded inversely, ‘is communicative, talkative’, and ‘is outgoing, sociable’; α = 0.65). We also assessed conscientiousness with three items (‘tends to be lazy,’ coded inversely, ‘works thoroughly’, and ‘does things effectively and efficiently’; α = 0.60). We assessed openness to experience with four items (‘is original, comes up with new ideas’, ‘is eager for knowledge’, ‘is imaginative’, and ‘appreciates artistic, aesthetic experiences’; α = 0.64). The participants responded to the personality items on a 7-point rating scale (1 = does not apply at all, 7 = fully applies). Lastly, we measured optimism with two items administered in 2014, ‘If you think about the future: Are you…’ (1 = pessimistic, 4 = optimistic; Trommsdorff, Citation1994) and ‘I am optimistic about my future’ (1 = completely disagree, 7 = fully agree; Diener et al., Citation2010); r = 0.48).

Control variables

Using participants’ chronological age in 2016, we defined five age groups, 16–24 years (emerging adults), 25–39 years (young adults), 40–54 years (middle-aged adults), 55–69 years (young-old adults), and 70+ (middle- and old-old adults). Sex was a binary variable (0 = male; 1 = female). We further controlled for the variables previously identified as PEAA correlates in the same dataset (Pavlova et al., Citation2023), which were partnership (1 = cohabiting with a partner, irrespective of marital status; 0 = not), subjective socioeconomic status (a mean of two items from the social ladder scale; Adler et al., Citation2000), and general health (using the single item ‘How would you describe your current health?’; 1 = bad; 5 = very good).

Analytical approach

We conducted the analyses in Mplus 8.5 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2017) and modeled all personality predictors as latent variables. To test our hypotheses (see preregistration at https://osf.io/24pw8, H1-H6), we regressed each of the three PEAA (outcome) variables on the predictors entered in blocks (only control variables, control and motivational variables, control and personality variables, and all of the predictors together). Following observation of a significant effect of one focal predictor in at least one domain, we compared the standardized regression coefficients between the domains using a z-test. To examine age differences in the effects on PEAA, we dichotomized the age variable (under 55 and 55+) and utilized a multiple-group approach to compare the unstandardized regression coefficients of the two age groups statistically (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2017). To avoid multiple significance testing, we first conducted an omnibus test of model equivalence (i.e. with the coefficients of interest constrained to be equal across age groups compared with all of the coefficients being free to vary). We handled all of the missing values with the full information maximum likelihood estimation, which utilizes all of the available information without imputing missing values (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2017).

Results

Measurement models

The measurement model for the personality variables included four latent variables, namely, extraversion and conscientiousness (three indicators each), openness to experience (four indicators), and optimism (two indicators). This model showed a satisfactory fit to the data, χ2 (48, N = 1,953) = 256.9, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.931, RMSEA = 0.047, SRMR = .040. The correlations among the latent variables ranged from 0.26 to 0.61 (see Online Supplement for the correlations between all predictors and outcomes).

Multiple regression analyses

shows the effects of all predictors. In the model with the individual motivational predictors (Model 1), the effect of health worry on PEAA was significant and positive only in the physical health domain (β = 0.14) and significantly more positive than the respective effect in the mental health domain (p = 0.012). The effect in the physical health domain remained significant in the final model with all predictors (β = 0.16; Model 3), so Hypothesis 1a was fully supported. The association between dementia worry and PEAA in the mental health domain was positive but only marginally significant in the model with motivational predictors as well as in Model 3 (both β = 0.06). Hence, Hypothesis 1b was only partially supported.

Table 2. Multiple regression analyses results.

Somewhat unexpectedly, we found the effect of the life goal of self-fulfillment on PEAA to be positive and significant only in the mental health domain (β = 0.08) and significantly more positive than the respective effect in the physical health domain (p = 0.002). In Model 3, this predictor had no significant effects. Thus, Hypothesis 2a was only partially supported. In full support of Hypothesis 2b, in Model 1, the life goal of civic engagement had a significant and positive effect in the social engagement domain (β = 0.23), and this effect was significantly more positive than the respective effects in the other two domains (p < 0.001 for both contrasts). In Model 3, the effect of this life goal remained significant in the social engagement domain (β = 0.22).

In the model with personality predictors (Model 2 in ), only openness to experience had positive and significant effects on PEAA in the mental health (β = 0.10) and social engagement (β = 0.17) domains. In Model 3, however, these effects disappeared, with no other personality predictors yielding significant effects. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was partially supported, there being no evidence for domain-specific effects of openness on PEAA in the mental health domain, while Hypotheses 3 and 5 were not supported. We conducted a post-hoc test of mediation, which showed that openness to experience was associated with PEAA in the physical health domain via health worry, b = 0.028, 95% CI [0.003, 0.062], β = 0.02, in the mental health domain via life goal of self-fulfillment, b = 0.030, 95% CI [0.006, 0.054], β = 0.02, and in the social engagement domain via the life goal of civic engagement, b = 0.102, 95% CI [0.071, 0.143], β = .06. These indirect effects were very small, though. The mediational role of dementia worry in the mental health domain, however, was not supported, b = 0.002, 95% CI [-0.003, 0.013], β = 0.01.

Furthermore, we explored age differences in the effects of interest. Judging by the omnibus tests of equality of effects of the motivational and personality variables across the two age groups, there were no age differences in any of the domains. Specifically, for the physical health domain, χ2 (8, N = 2,007) = 8.6, ns, for the mental health domain, χ2 (8, N = 2,007) = 14.5, ns, and for the social engagement domain, χ2 (8, N = 2,007) = 16.5, ns. Lastly, as older adults had very different socialization experiences in the former East and West Germany before 1989 (time of unification), in supplementary analyses, we controlled for the region of residence (i.e. East vs. West) and examined possible regional differences in the effects of interest. As a control variable, region was associated with PEAA. In line with prior findings on a different dataset (Pavlova & Silbereisen, Citation2012), residents of the former East Germany reported significantly higher PEAA, particularly middle-aged and older participants in the mental health domain. However, the pattern of effects described above regarding motivational and personality-related correlates of PEAA remained identical, and no significant regional differences emerged therein.

Discussion

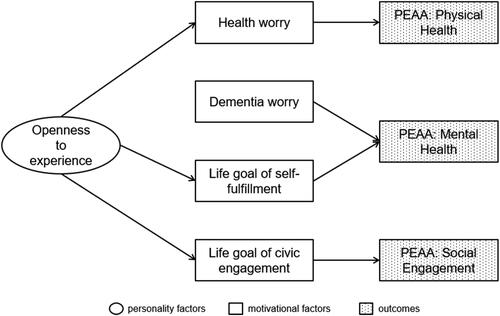

The primary objective of this study was to examine the role of motivation and personality factors in domain-specific PEAA. illustrates our main findings. Overall, domain-specific motivation was consistently associated with PEAA in matching domains. Among personality traits, only openness to experience was related to higher PEAA (almost) across domains, but these effects were mediated by domain-specific motivation. In other words, expectations for active aging appear to reach individuals whose personal concerns resonate with the corresponding dimensions of active aging (e.g. health maintenance). In turn, motivation congruent with active aging appears to be facilitated by openness to experience. Our findings further support the domain specificity of PEAA and underscore the importance of openness and congruent motivation in perceiving expectations for active aging.

Figure 1. Overview of central findings. PEAA: perceived expectations for active aging. All effects shown were positive. Predictors whose effects were never significant are omitted for clarity. Dementia worry had a marginally significant effect in both the model with motivational predictors and the final model (with all predictors included). The effect of the life goal of self-fulfillment was not significant in the final model.

As expected, health worry was significantly associated with higher PEAA in the physical health domain, while dementia worry had a similar, but only marginally significant, effect in the mental health domain. Furthermore, although we expected to find its association with PEAA in both health domains, the life goal of self-fulfillment was related to higher PEAA in the mental but not in the physical health domain. That is, individuals to whom self-fulfillment was more important perceived higher social expectations to stay mentally but not physically fit. Maybe the notion of self-realization strongly resonates with the concept of mental health (Ryff & Singer, Citation2008), making individuals more sensitive to social expectations in this domain. In contrast, physical health can be universally important, irrespective of one’s ambition to fulfill their potential. Finally, in line with our hypotheses, the life goal of civic engagement was positively and significantly related to PEAA in the social engagement domain.

Regarding personality, only openness to experience exhibited significant positive associations with PEAA in the mental health and social engagement domains. This finding may be attributable to open individuals’ preference for cognitive stimulation and their tendency to embrace the ideals of civic participation (Dinesen et al., Citation2014; Price et al., Citation2015). However, these effects became nonsignificant when all of the predictors were factored into the equation. As our post-hoc analyses showed, the effects of openness to experience appeared to be channeled through domain-specific motivation (). This finding may highlight the specific manifestations of openness to experience that contribute to PEAA by virtue of congruence. Indeed, more open individuals were found to hold more intrinsic life goals (Reisz et al., Citation2013) and to be better aware of stressors potentially affecting their health (Furnham et al., Citation2012). We did not find significant effects of other personality traits on PEAA. This may imply that their effects are contingent on unexamined contextual or motivational factors that are more closely related to active aging. Alternatively, the mechanisms behind their effects on health and social engagement (Baek et al., Citation2016) may be independent from perceiving the corresponding social expectations. Generally, though, the effects of motivational predictors and openness were rather small, explaining 1–5% of variance in PEAA—comparable to the effects of objective, socio-structural factors.

Our study had several strengths but also limitations. The SOEP-IS is the first nationally representative survey to have included the measures of domain-specific PEAA, for which reason our findings can be generalized to the German population. We preregistered our hypotheses and the analysis plan for this study and relied on strict ad-hoc and post-hoc criteria in the evaluation of results. Since the SOEP-IS is a large-scale, multi-topic, and multi-purpose survey, many constructs were assessed with a few or single items. This survey was suitable for our domain-specific approach, but the measurement of personality traits was not optimal. Future studies might employ a more comprehensive measurement of personality traits (e.g. a facet-level approach), which may yield more domain-specific associations with PEAA. To mitigate the measurement error, we employed latent variable modeling wherever possible. Furthermore, we used self-report measures, which may be prone to social desirability bias but can also be considered appropriate for subjective constructs (such as PEAA).

Although using predictors from several previous waves of the survey was an advantage, the long measurement intervals between certain predictors and the outcomes may have affected some of the results (e.g. the four-year interval between dementia worry and PEAA). Last but not least, the correlational design precluded us from establishing causality. Indeed, it is important to consider the possibility of reverse causation in our findings. Instead of, or in addition to, perceiving more expectations for active aging due to their motivations, individuals may set or revive the corresponding goals or feel more worried about their health in response to PEAA. Furthermore, although personality traits are relatively stable, they can change with age and due to life events (Specht et al., Citation2011). Hence, PEAA facilitating openness to experience—especially given the broad age range of our sample—remains a possibility. Future research may address these and other potential outcomes of PEAA, including well-being and behavioral consequences of perceiving expectations for active aging in a particular domain. The role of motivational factors, which appear to enhance receptiveness to PEAA, deserves further attention (e.g. do only motivated individuals experience the favorable outcomes of PEAA?).

Several practical implications can be drawn from our study. Public-health and active-aging campaigns should address older adults’ personal goals and concerns. For instance, regarding health-related worries, active-aging campaigns may showcase lifestyles and activities that help prevent the prevalent health issues of older age (e.g. physical health: sensory impairments, osteoporosis; mental health: dementia; World Health Organization, Citation2015). Concerning personal goals, specific activities that speak to a variety of personal interests (e.g. traveling, helping out with grandchildren, or learning new skills) can be emphasized. In addition to supporting the preferential processing of information congruent with one’s goals and concerns, our findings suggested that this process is independent of age. Thus, given that health behaviors and lifestyles in early and mid-adulthood strongly predict old-age outcomes (World Health Organization, Citation2002), it is warranted to target young and middle-aged adults in public-health campaigns ultimately meant to foster healthy aging.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study because it analyses an existing dataset. The Socio-Economic Panel complies with ethical research standards.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (18.8 KB)Acknowledgments

Data from the Innovation Sample of the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP-IS) were made available by DIW Berlin through a data distribution contract. We thank DIW Berlin for including our items in the SOEP-IS 2016.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We excluded agreeableness because of low scale reliability in our subsample (α = .45) and because a more proximal construct related to PEAA in the social engagement domain, the life goal of civic engagement, was available. Furthermore, instead of neuroticism—arguably a more general construct—we opted for health and dementia worries as more proximal predictors of domain-specific PEAA. No other comparable domain-specific constructs for the remaining personality traits were available in the dataset.

2 We focused on dementia worry because dementia prevalence rises exponentially with age. Moreover, dementia worry was found to be relatively common in the general population of Germany (Hajek & König, Citation2020) and thus suitable for all age groups in our sample.

3 We preregistered a hypothesis about the possible moderating effects of conscientiousness on the relationship between motivational constructs and PEAA, which none of the analyses supported. To reduce the complexity of the model, we decided not to report these analyses in this paper and explored the main effects of conscientiousness on PEAA.

References

- Ackermann, K. (2019). Predisposed to volunteer? Personality traits and different forms of volunteering. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 48(6), 1119–1142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764019848484

- Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychology, 19(6), 586–592. https://doi.org/10.1037//0278-6133.19.6.586

- Baek, Y., Martin, P., Siegler, I. C., Davey, A., & Poon, L. W. (2016). Personality traits and successful aging: Findings from the Georgia Centenarian Study. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 83(3), 207–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415016652404

- Baltes, P. B. (1987). Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental Psychology, 23(5), 611–626. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.23.5.611

- Basevitz, P., Pushkar, D., Chaikelson, J., Conway, M., & Dalton, C. (2008). Age-related differences in worry and related processes. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 66(4), 283–305. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.66.4.b

- Bauer, J. M., Brand, T., & Zeeb, H. (2020). Pre-migration socioeconomic status and post-migration health satisfaction among Syrian refugees in Germany: A cross-sectional analysis. PLOS Medicine, 17(3), e1003093. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003093

- Behzadnia, B., Deci, E. L., & DeHaan, C. R. (2020). Predicting relations among life goals, physical activity, health, and well-being in elderly adults: A self-determination theory perspective on healthy aging. In B. Ng & G. Ho (Eds.), Self-determination theory and healthy aging (pp. 47–71). Springer Singapore.

- Bowling, A. (2008). Enhancing later life: How older people perceive active ageing? Aging & Mental Health, 12(3), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860802120979

- Brandtstädter, J., & Rothermund, K. (2002). The life-course dynamics of goal pursuit and goal adjustment: A two-process framework. Developmental Review, 22(1), 117–150. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.2001.0539

- Brosschot, J. F. (2002). Cognitive-emotional sensitization and somatic health complaints. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 43(2), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9450.00276

- Buchinger, L., Richter, D., & Heckhausen, J. (2022). The development of life goals across the adult life span. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 77(5), 905–915. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbab154

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2010). Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 879–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006

- de Paula Couto, M. C., Fung, H. H., Graf, S., Hess, T. M., Liou, S., Nikitin, J., & Rothermund, K. (2022). Antecedents and consequences of endorsing prescriptive views of active aging and altruistic disengagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 807726. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.807726

- de Paula Couto, M. C., & Rothermund, K. (2022). Prescriptive views of aging: Disengagement, activation, wisdom, and dignity as normative expectations for older people. In Y. Palgi, A. Shrira, & M. Diehl (Eds.), Subjective views of aging (vol. 33, pp. 59–75) Springer International Publishing.

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

- Dinesen, P. T., Nørgaard, A. S., & Klemmensen, R. (2014). The civic personality: Personality and democratic citizenship. Political Studies, 62(1_suppl), 134–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12094

- Elder, G. H. (1974). Children of the great depression: Social change in life experience. University of Chicago Press.

- Fasel, N., Vauclair, C.-M., Lima, M. L., & Abrams, D. (2021). The relative importance of personal beliefs, meta-stereotypes and societal stereotypes of age for the wellbeing of older people. Ageing and Society, 41(12), 2768–2791. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20000537

- Fleck, J. I., Patel, P., Riley, E., & Ferri, C. V. (2023). Mindset matters: Contributions from grit and growth mindsets to successful aging. Aging & Mental Health, 28(5), 819–827. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2023.2280626

- Foster, L., & Walker, A. (2015). Active and successful aging: A European policy perspective. The Gerontologist, 55(1), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu028

- Furnham, A., Strait, L., & Hughes, D. J. (2012). Modern health worries and personality. Personality and Mental Health, 6(3), 242–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.1187

- Gerlitz, J. Y., Schupp, J. (2005). Zur Erhebung der Big-Five-basierten Persönlichkeitsmerkmale im SOEP [On the survey of the Big Five-based personality traits in the SOEP] (Research Report 4). DIW, Berlin. https://www.diw.de/documents/publicationen/73/43490/rn4.pdf

- Hajek, A., & König, H.-H. (2020). Fear of dementia in the general population: Findings from the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP). Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 75(4), 1135–1140. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200106

- Heckhausen, J., Wrosch, C., & Schulz, R. (2019). Agency and motivation in adulthood and old age. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 191–217. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103043

- Hunt, S., Wisocki, P., & Yanko, J. (2003). Worry and use of coping strategies among older and younger adults. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 17(5), 547–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6185(02)00229-3

- Jackson, J. J., Hill, P. L., Payne, B. R., Parisi, J. M., & Stine-Morrow, E. A. L. (2020). Linking openness to cognitive ability in older adulthood: The role of activity diversity. Aging & Mental Health, 24(7), 1079–1087. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1655705

- Kashdan, T. B., Rose, P., & Fincham, F. D. (2004). Curiosity and exploration: Facilitating positive subjective experiences and personal growth opportunities. Journal of Personality Assessment, 82(3), 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8203_05

- Kessler, E.-M., Bowen, C. E., Baer, M., Froelich, L., & Wahl, H.-W. (2012). Dementia worry: A psychological examination of an unexplored phenomenon. European Journal of Ageing, 9(4), 275–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-012-0242-8

- Kessler, E.-M., & Warner, L. M. (2023). Age ismus—Altersbilder und Altersdiskriminierung in Deutschland [Ageism – Views on aging and age discrimination in Germany]. Antidiskriminierungsstelle des Bundes.

- Klinger, E. (1996). Emotional influences on cognitive processing, with implications for theories of both. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior (pp. 168–189). The Guilford Press.

- Kornadt, A. E., & Rothermund, K. (2011). Contexts of aging: Assessing evaluative age stereotypes in different life domains. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66(5), 547–556. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbr036

- Kornadt, A. E., & Rothermund, K. (2015). Views on aging: Domain-specific approaches and implications for developmental regulation. In M. Diehl & H.-W. Wahl (Eds.), Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics: (Vol. 35). Subjective aging: New developments and future directions (pp. 121–144). Springer Publishing Company.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Lechner, C. M., Obschonka, M., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2017). Who reaps the benefits of social change? Exploration and its socioecological boundaries. Journal of Personality, 85(2), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12238

- Lessenich, S. (2015). From retirement to active aging: Changing images of ‘old age’ in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. In C. Torp (Ed.), Challenges of aging (pp. 165–177) Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (2003). Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Muthén, L. K., Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus user guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. https://www.statmodel.com/html_ug.shtml

- North, M. S., & Fiske, S. T. (2013). Act your (old) age: Prescriptive, ageist biases over succession, consumption, and identity. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(6), 720–734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213480043

- Pavlova, M. K., Radoš, S., Rothermund, K., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2023). Age, individual resources, and perceived expectations for active aging: General and domain-specific effects. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 97(3), 267–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/00914150221112294

- Pavlova, M. K., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2012). Perceived level and appraisal of the growing expectations for active ageing among the young-old in Germany. Research on Aging, 34(1), 80–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027511416371

- Pavlova, M. K., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2016). Perceived expectations for active aging, formal productive roles, and psychological adjustment among the young-old. Research on Aging, 38(1), 26–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027515573026

- Pinquart, M., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2004). Human development in times of social change: Theoretical considerations and research needs. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(4), 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250344000406

- Pocnet, C., Popp, J., & Jopp, D. (2021). The power of personality in successful ageing: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. European Journal of Ageing, 18(2), 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-020-00575-6

- Pollet, T. V., Roberts, S. G. B., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2011). Extraverts have larger social network layers: But do not feel emotionally closer to individuals at any layer. Journal of Individual Differences, 32(3), 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000048

- Price, E., Ottati, V., Wilson, C., & Kim, S. (2015). Open-minded cognition. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(11), 1488–1504. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215600528

- Reisz, Z., Boudreaux, M. J., & Ozer, D. J. (2013). Personality traits and the prediction of personal goals. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(6), 699–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.05.023

- Ryan, R. M., Huta, V., & Deci, E. L. (2008). Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 139–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9023-4

- Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 13–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0

- Socio-Economic Panel. (2024). About us. Retrieved 27 July 2024, from https://www.diw.de/en/diw_01.c.600489.en/about_us.html#c_624240

- Socio-Economic Panel. (2018). SOEP-IS companion. http://companion-is.soep.de/Innovative%20Modules/Ageing%20in%20a%20Changing%20Society.html

- Specht, J., Egloff, B., & Schmukle, S. C. (2011). Stability and change of personality across the life course: The impact of age and major life events on mean-level and rank-order stability of the Big Five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(4), 862–882. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024950

- Trommsdorff, G. (1994). Zukunft als Teil individueller Handlungsorientierungen [Future as a part of individual action orientations]. In E. Holst, J. P. Rinderspracher, & J. Schupp (Eds.), Erwartungen an die Zukunft: Zeithorizonte und Wertewandel in der sozialwissenschaftlichen Diskussion (pp. 45–76). Campus Verlag.

- Turner, S. G., & Hooker, K. (2022). Are thoughts about the future associated with perceptions in the present?: Optimism, possible selves, and self-perceptions of aging. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 94(2), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415020981883

- Wirth, M., de Paula Couto, M. C., Pavlova, M. K., & Rothermund, K. (2023). Manipulating prescriptive views of active aging and altruistic disengagement. Psychology and Aging, 38(8), 854–881. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000763

- World Health Organization. (2002). Active ageing: A policy framework. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/67215

- World Health Organization. (2015). World report on ageing and health. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/186463

- Zweck, B., & Glemser, A. (2018). SOEP-IS 2016 – Methodenbericht zum Befragungsjahr 2016 des SOEP-Innovationssamples [Method report for the 2016 survey year of the SOEP innovation sample] (SOEP Survey Papers). SOEP. https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.579466.de/diw_ssp0481.pdf