ABSTRACT

One of the consequences of the eurozone crisis in the countries of ‘Old Southern Europe’ is the shift from pro-European to eurosceptic attitudes. Our overarching goal is to assess whether these critical stances towards the EU are more conjunctural or long-lasting. We further aim to analyse the determinants of euroscepticism at the micro-level before, during and after the emergence of the eurozone crisis. Our analysis reveals that euroscepticism is of a more conjunctural nature in Spain and Portugal, yet more structural in Italy and Greece. Moreover, our findings show that cultural and political/institutional approaches, but also political/ideological ones, better explain South European euroscepticism before, during and after the crisis when compared to utilitarian/economic approaches.

Up to the early 1990s, a widespread ‘permissive consensus’ was predominant on European integration issues. Since then, citizens’ opinion on the process of European integration has moved from this indifference and unquestioned support into a phase of ‘constraining dissensus’ – i.e. a period in which public opinion has explicitly displayed its opposition to the European project (Hooghe & Marks Citation2009; Down & Wilson Citation2008; Hutter & Grande Citation2014). The shift away from the original elite-centred view of European integration is perhaps most obvious after the onset of the eurozone crisis. Since the crisis, there has been an ongoing debate in most European Union (EU) member-states about the role and scope of EU institutions. It could be argued that the politicisation of European integration, that is, the increased importance of public and party preferences on European integration in elections and referenda, has changed the content, as well as the process of decision-making, with parties making room for a more eurosceptic public (Hooghe & Marks Citation2009, Citation2018).

Under these circumstances, a region which has gained scholarly attention with regard to contemporary euroscepticism is Southern Europe. Before the onset of the eurozone crisis,Footnote1 this used to be a generally pro-European region. With the emergence of the crisis, there was a steep decline in support for the EU in ‘Old Southern Europe’ (Italy, Greece, Spain and Portugal),Footnote2 giving rise to a clear indication that the ‘EU’s most pro-European’ region (Hooghe & Marks Citation2007; Llamazares & Gramacho Citation2007; Schmitt & Teperoglou Citation2015) was turning towards euroscepticism (Braun & Tausendpfund Citation2014; Belchior Citation2015).

The ultimate objective of this article is to provide an overview of the rise of eurosceptic attitudes in these four countries, and to analyse the factors that underpin (or impede) the adoption of eurosceptic attitudes and how these factors evolved throughout the eurozone crisis. An important point in our study is that we aim to highlight country specificities. In other words, ‘Old Southern Europe’ is not considered a unitary group for the study of euroscepticism. On the contrary, we seek to investigate whether we can detect differences between these countries and in particular between the bailed-out countries (Greece and Portugal) on one hand, and Spain and Italy on the other (although Spain had a bank bailout, this did not affect sovereignty to the extent experienced by Greece and Portugal). Furthermore, are the determinants of euroscepticism different at the three points of time of our study (2009, 2014 and 2018) or are they the same irrespective of the onset of the crisis? In a broader perspective, the article aims to answer the question whether the critical stances towards the European project that are observed after the onset of the economic crisis in the four countries are more conjunctural and related to the eurozone crisis or alternatively, have become more enduring and deep-seated.

The structure of the article is as follows. In the next section, we briefly present the context in which increased euroscepticism occurred in Southern Europe. In the third section, we focus on our theoretical framework. In the fourth section our hypotheses are formulated, followed by the presentation of the data, variables and method. Next, we provide an aggregate-level overview of the evolution of public opinion in Southern Europe towards the EU over the timeframe of our study. The last section discusses the determinants of euroscepticism at the micro-level, and the article ends with some concluding remarks.

The eurozone crisis and the new euroscepticism

Before the emergence of the eurozone crisis, EU membership was perceived as a positive thing for most South Europeans, who used to associate the EU with economic growth, rising standards of living and a sought-after institutional framework for the modernisation of the state and economy. Nevertheless, in all four countries there were some surges in euroscepticism even before the onset of the crisis, but mostly related to the national context (Verney Citation2011) and not to the same extent.

In 2010 the global credit crunch morphed into the eurozone crisis with Greece at its epicentre. The crisis soon spread to other countries in the periphery of the eurozone and in particular to other South European countries, exerting unprecedented pressure on their political systems. The Greek and Portuguese governments were forced to request the activation of emergency funds (bailout packages that rely on EU-IMF loans, the so-called Memorandum of Understanding/MoU), while Spain asked for a bank bailout in July 2012.Footnote3 Italy did not have to go through formal bailouts, but was forced to implement severe austerity policies imposed by the EU.Among the four countries of our study, Greece was the most severely affected by the economic and political fallout of the crisis. The old party system changed beyond recognition from 2009 to 2015 (Teperoglou & Tsatsanis Citation2014; Tsatsanis & Teperoglou Citation2016; Verney Citation2014). In Italy, the economic recession and rising unemployment derived from austerity led in 2011 to the resignation of a prime minister, who was then succeeded by an EU-sanctioned technocrat as head of government. Subsequently, the results of both the 2013 and 2018 national elections showed a seismic shift in the country’s political scene. Similarly, the national election of 2015 in Spain signalled the end of the two-party system that was dominant since 1982 based on PSOE (Partido Socialista Obrero Español ‒ Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party) and the centre-right PP (Partido Popular ‒ People’s Party). Mainly due to the rise of two national-wide challenger parties, Podemos (We Can) from the centre-left and Ciudadanos (Citizens) from the centre-right, the Spanish political arena in the period of economic crisis has changed significantly and moved towards a multi-party system (Orriols & Cordero Citation2016). Conversely, despite the fact that Portugal was, with Greece, one of the bailed-out South European countries, we cannot detect similar fundamental changes in the Portuguese party system. Perhaps its most striking transformation relates to the changing inter-party dynamics that led to collaboration by the parties of the left for the first time since the transition to democracy in the mid-1970s.

At the party level, euroscepticism in Italy has been mainly driven by the populist and eurosceptic party M5S (Movimento 5 Stelle – Five Star Movement) or by the far-right LN (Lega Nord – Northern League). In contrast, especially in Greece, but also in Spain and in Portugal, euroscepticism at the party level is mainly associated with leftist (and communist) ideology (Lisi & Tsatsanis Citation2018). In Spain, the rise of Podemos, a left-wing party founded in the aftermath of the social protests of 2011, challenged the consensus on EU integration. Therefore, a main characteristic in the study of euroscepticism for Southern Europe concerns the different political legacies related to eurosceptic stances. With the exception of Italy, the other three countries deviate from the common western-northern European pattern in this regard, where the adoption of less pro-European stances is mainly found among political actors belonging to the right and extreme right (Van Elsas, Hakhverdian & Van der Brug Citation2016, pp. 1192–1194; Lisi & Tsatsanis Citation2018).

Previous studies have focused on the effects of the economic crisis on the rise of euroscepticism (e.g. Braun & Tausendpfund Citation2014; Freire, Teperoglou & Moury Citation2014; Serricchio, Tsakatika & Quaglia Citation2013), examining only the period leading up to the crisis and its early manifestations. In the literature, there are various studies on these four countries with similar research questions, but most of them concentrate on the period at the beginning of the crisis (e.g. Clements, Nanou & Verney Citation2014; Jiménez & de Haro Citation2011; Serricchio Citation2012). To our knowledge, the only recent study on the rise of euroscepticism addressing Southern Europe exclusively (also including Cyprus and Malta) was published by Verney (Citation2018), offering an analysis of the evolution of euroscepticism in Southern Europe using aggregate findings.

Our contribution aims to fill this research gap by analysing euroscepticism in the four countries before the onset of the eurozone crisis, during its peak and after its outbreak both at the aggregate and micro-level.Footnote4 We are aware that it is rather early to analyse the long-term consequences of the crisis on attitudes towards the EU in Southern Europe. Nevertheless, we believe that as the period of economic turmoil gradually recedes into the past, the time has come to start to shed light on the determinants of this new euroscepticism.

Determinants of euroscepticism: competing theoretical perspectives

Euroscepticism has been acknowledged as being of a complex multidimensional nature (e.g. Lubbers & Scheepers Citation2005; Boomgaarden et al. Citation2011), being traditionally defined as ‘contingent or qualified opposition, as well as incorporating outright and unqualified opposition to the process of European integration’ (Taggart Citation1998, p. 366). Most of the studies on euroscepticism construe elite and party oppositions to European integration based mainly on the classic distinction between ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ euroscepticism as originally formulated by Taggart (Citation1998) and its consequences for the national political arena. The literature reveals growing interest in the study of EU public opinion since the late 1980s as a result of the consequences of market integration (Inglehart, Rabier & Reif Citation1991; Hooghe & Marks Citation2009), whereas emphasis is given to the analysis of the predictors of anti-European stances (e.g. Hooghe & Marks Citation2009; McLaren Citation2007). In this section of the article, we will briefly present the main theoretical approaches to explaining public opinion stances towards the EU.

The cognitive mobilisation approach

Cognitive mobilisation is defined by the (high) level of education and by (high) interest in discussing politics and/or higher political involvement (Inglehart Citation1970; Janssen Citation1991). The latter variable is related to exposure to information on European matters and consequently to a higher level of ‘EU political sophistication’ (e.g. awareness of how the EU works). Citizens who are more cognitively mobilised tend to adopt more pro-European stances compared to those who are less cognitively mobilised.

The utilitarian/economic approach

Attitudes towards European integration are analysed in terms of economic effects (Gabel & Palmer Citation1995; Gabel Citation1998; Eichenberg & Dalton Citation1993). The main underlying rationale is that the stances of European citizens towards the process of European integration are influenced by a trade-off between the benefits and costs of their country’s EU membership (both for retrospective and prospective evaluations). EU citizens are able to make a rational evaluation of the economic consequences of European integration both for themselves (‘egocentric utilitarian approach’) and for their country’s economy (‘subjective sociotropic utilitarian approach’) (Hooghe & Marks Citation2009; Serricchio Citation2012). Moreover, Gabel and Palmer (Citation1995) and Gabel (Citation1998) argue that citizens’ support for integration is positively related to their welfare gains from integration policy. In both studies they predict that ‘human capital level of education, income and occupational skills’ is an important proxy for citizen support for integration. Their analysis reveals that those who are less well educated, with low income and manual workers tend to be less supportive of the EU (Gabel Citation1998, p. 343). However, education and occupational skills are also positively correlated with cognitive skills (Gabel Citation1998).

This interest-based approach was the most prominent in the relevant literature up to the mid-1990s. In the aftermath of the Maastricht treaty, some studies have shown that the relative impact of economic considerations in explaining the rise of euroscepticism has decreased, while on the other hand the impact of cultural aspects has increased (Schäfer et al. Citation2020). In other words, some scholars moved away from the economic calculus approach to understanding euroscepticism, claiming that possible threats to attitudes towards European integration could not be of an economic nature only, but could also involve other factors such as the strength of national versus European identity.

The national identity approach

The third main approach to a possible explanation of the endorsement of eurosceptic stances is based on national identity (e.g. Carey Citation2002; Hooghe & Marks Citation2005, Citation2009; McLaren Citation2007). This theory primarily flourished when EU citizens became more doubtful about the process of the European integration, a trend which has been characterised as the ‘post-Maastricht blues’ (Eichenberg & Dalton Citation2007). As Van Elsas and Van der Brug (Citation2015, p. 202) argue, ‘Maastricht made citizens aware of the implications of the EU for national interests, sovereignty, and identity, thereby giving right-wing citizens a reason to become eurosceptical’. A further development was the introduction of EU citizenship and the idea of European identity. This approach stresses the multilevel nature of governance in the EU, the loss of sovereignty for nation states and the debate around multiculturalism versus national identity. National identity effects are likely to become increasingly pertinent to explain attitudes towards European integration as a consequence of the national politicisation of EU issues (Hooghe & Marks Citation2009). In particular, national identity effects on euroscepticism can be potentiated by the division of the political elite on European integration in the country (Hooghe & Marks Citation2005).

The political/institutional approach

Another approach focuses on national peculiarities rather than links with the actual process of European integration (e.g. Armingeon & Ceka Citation2014; Serricchio, Tsakatika & Quaglia Citation2013). It is argued that euroscepticism is linked to the (negative) performance of the national government, as well as to (low) levels of trust in national institutions. However, findings from previous studies are inconclusive regarding this approach (McLaren Citation2007). Some authors claim that there is a spill-over effect from dissatisfaction with the national government to the EU sphere (e.g. Anderson Citation1998), while others argue that the higher the level of dissatisfaction with national government institutions, the more pronounced will be the adoption of positive stances towards the EU (e.g. Sánchez-Cuenca Citation2000).

The pertinent literature of this approach includes two more plausible explanations of the determinants of euroscepticism, referring to input-oriented factors in response to the performance of the system (Mcevoy Citation2016). The first approach associates eurosceptic positions with a negative evaluation of democracy at the European level (e.g. Armingeon & Ceka Citation2014; Serricchio, Tsakatika & Quaglia Citation2013). In particular, the literature links the debate on the EU democratic deficit with euroscepticism. The second one emphasises a possible connection between the feeling of political efficacy, that is, the feeling that the citizens’ voice is taken into account in the EU political process, and the issue of political support for the EU (e.g. Braun & Tausendpfund Citation2014, p. 239; Mcevoy Citation2016). This effect seems to downplay short-term utilitarian concerns, as citizens who feel their voice is represented are more likely to show support for the EU regardless of their perceptions of the economy (Mcevoy Citation2016).

Political/ideological approach

Previous studies argue that supporters of centrist parties tend to adopt more pro-European stances, while voters of both extreme right and extreme left parties are considered more eurosceptic (see Van Elsas & Van der Brug Citation2015; Van Elsas, Hakhverdian & Van der Brug Citation2016). The origins of left and right-wing euroscepticism are, however, distinctly different. Radical left-wing parties derive their euroscepticism from their support for the welfare state and opposition to market liberalisation. On the other hand, radical right-wing parties are wary of the threat posed by European integration to national sovereignty via the transfer of powers from the nation-state to supranational institutions and to national culture due to the increase of immigration (Van Elsas, Hakhverdian & Van der Brug Citation2016). In this regard, Van Elsas and Van der Brug (Citation2015, pp. 205–206) demonstrate that voters on the left are more fearful of losing social security than those on the right, and that right-wing voters are more afraid of losing national identity than left-wing voters. In this vein, in Southern Europe, the legacy of the party systems prior to the emergence of the eurozone crisis seems to explain these countries’ deviance from the rest of Europe regarding patterns of euroscepticism (Lisi & Tsatsanis Citation2018).

Hypotheses and expectations: knowledge, utility, identity, institutional trust, efficacy or left-right orientation?

Our first hypothesis draws on cognitive mobilisation theory. Here, we aim to figure out whether less knowledge about the EU increases the likelihood of eurosceptic attitudes in Southern Europe.

Hypothesis 1: Eurosceptic stances will tend to be higher for citizens with a low level of knowledge about the EU, when compared to citizens with a higher level of knowledge (H1)

Some scholars have demonstrated that during the crisis, there was an increase in the explanatory power of utility and economic calculations, as opposed to identity factors, in public support for European monetary integration (Hobolt & Wratil Citation2015). This conclusion is most likely dependent on the issue at stake being economic, stimulating citizens to consider it ‘more in terms of economic self-interest and less in terms of their national identity’ (Hobolt & Wratil Citation2015, p. 252). Freire, Teperoglou and Moury (Citation2014) found that both the economic crisis and the political responses of the EU to austerity policies contributed to a strong increase of euroscepticism in Greece and Portugal between 2008 and 2012 (see also Teperoglou et al. Citation2014). Andreadis et al. (Citation2014), in focusing on the rise of euroscepticism in Italy and Greece during the period of 2012–13, conclude that the increase in negative attitudes towards Europe in both countries is closely related to the attribution of blame to the EU for the economic crisis.

Our general expectation is thus that the emergence of the crisis in the South European countries led to an increase in euroscepticism due to a decreasing perception of European integration’s utilitarian value, both egocentric and sociotropic. We expect this to be more prominent in Greece and Portugal, the two bailed-out countries in our study, compared to Spain and Italy. Moreover, utilitarian considerations are expected to play a significant role in citizens’ support for the EU (especially in Greece and Portugal) whenever they can establish a link between their own economic situation and EU integration policies.

In order to test sociotropic economic utilitarianism, our hypothesis stands as follows:

Hypothesis 2a: The more negative the evaluation of the prospective situation of the national economy, the more pronounced the eurosceptic stances especially at the peak of the crisis in Greece and Portugal (H2a)

To test egocentric economic utilitarianism, we formulated the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2b: The more negative the evaluation of the current economic situation of the household, the more pronounced the eurosceptic stances especially at the peak of the crisis in Greece and Portugal (H2b)

Hypothesis 2c: Citizens whose individual-level characteristics are associated with lower socioeconomic status (manual workers or unemployed) are more inclined to adopt eurosceptic stances especially at the peak of the crisis in Greece and Portugal (H2c)

Previous studies carried out at the beginning of the eurozone crisis concluded that, although the utilitarian approach explains variation in EU attitudes in the countries most affected by the crisis, national identity was found to be more important in explaining euroscepticism (Serricchio, Tsakatika & Quaglia Citation2013). National politicisation of EU issues and elite conflict has augmented as a result of the economic crisis (Hobolt & Wratil Citation2015), which contributes to an expected increased national identity effect in ‘Old Southern Europe’ during the course (and as a consequence) of the crisis. Our hypothesis is based on exclusive national identity.

Hypothesis 3: Citizens who are more inclined to adopt an exclusive national identity are more likely to espouse eurosceptic stances (H3)

Armingeon and Ceka (Citation2014) demonstrated that the erosion of trust in the EU between 2007 and 2011 (mostly in Greece and Portugal, but also in the other countries under external financial intervention) is much more likely to be due to policies of national governments and developments in the national economy than to the direct effect of EU policies. We expect that the low levels of trust in the national government will be a significant predictor, especially at the peak of the crisis, given that all four countries experienced widespread discontent and cynicism in the national political arena.

Hypothesis 4: An increased level of political distrust of the national government (especially during the peak of the crisis) will be associated with stronger eurosceptic stances in the four countries (H4)

Furthermore, previous studies on South European countries found that negative attitudes of citizens towards the EU were closely related to their opinions on the political responses of the EU during the crisis (Andreadis et al. Citation2014; Freire, Teperoglou & Moury Citation2014; Teperoglou, et al. Citation2014). In order to assess how citizens’ evaluations of EU performance affects euroscepticism, we worked on the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5: The more negative the evaluation of EU democracy (especially during the peak of the crisis), the stronger the eurosceptic stances in the four countries (H5)

Based on the political/institutional approach, we also include a hypothesis pertaining to political efficacy. We expect that the feeling of political efficacy towards the EU was a stronger predictor of euroscepticism before the crisis emerged, and that it has declined since then, as explained above.

Hypothesis 6: The lower the level of citizens’ political efficacy towards the EU (especially before the emergence of the crisis) the stronger the eurosceptic stances in the four countries (H6)

Finally, we expect that euroscepticism in Southern Europe is moulded by the legacy of the party systems prior to the emergence of the crisis, characterised by left-wing eurosceptic parties in Portugal and Greece (the communist and radical left parties), and by right-wing eurosceptic parties in Italy (e.g. Lega Nord). Spain had the least eurosceptic party system of this group before the onset of the crisis (Lisi & Tsatsanis Citation2018, p. 10), a scenario that started changing with the rise of Podemos. This change has probably been accelerated by the entry of extreme right party Vox into parliament at the regional and national level, in 2018 and 2019 respectively (which is however beyond the timeframe covered in our article).

Hypothesis 7: Eurosceptic stances are expected to be more linked in Italy to extreme right positions on the left-right axis compared to the other three countries, whereas in Greece, Spain and Portugal the adoption of eurosceptic stances is more linked to leftist positions on the left-right axis (H7)

Operationalisation: data, variables and method

In all four countries, as presented below, we observe a sharp decline of support for the EU during the period of the eurozone crisis. We use the year 2009 as a benchmark for the period before the onset of the crisis. This year has been commonly used in studies on Southern Europe to identify the moment before the crisis exploded (e.g. Freire, Teperoglou & Moury Citation2014). In 2009 South European economies were already in, or entering, recession, but it was only in 2013–2014 that the eurozone crisis deeply affected these countries. The second period of our analysis is the peak of the crisis (2014). This year corresponds to the moment citizens’ critical views were at a high point, when compared to the time before the emergence of the crisis or the period of new equilibrium and stabilisation in 2018. We argue that for the four countries, 2014 generally represents the moment when the economic consequences of the crisis were more severely felt by the population.

The third phase began in 2018, bringing renewed balance and stability. This year appears to be a turning point as most macro-level socioeconomic indicators become positive.Footnote5 In order to test our hypotheses, we used data from the Eurobarometer surveys series which enabled us to study the predictors of euroscepticism at the individual level of analysisFootnote6 in the four countries, using comparable variables in the three distinctive time points.

The dependent variable of our study is the following question about the image of the EU: ‘In general, does the EU conjure up for you a very positive, fairly positive, neutral, fairly negative, or very negative image?’. We used this question for two reasons. Firstly, it is the only appropriate indicator available in all three Eurobarometer surveys. Secondly, it captures a more general sentiment towards Europe – which constitutes the core of our research questions – with no reference to any benefits from EU membership or specific policy integration stances.Footnote7

In order to depict the determinants of euroscepticism in Southern Europe, we ran an ordered logit model as our dependent variable is an ordinal one (see Table A1 in the online appendix, available at https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2020.1805878 which summarises the variables used in the model with the exact wording of the questions and the scales). Following the hypotheses presented above, the independent variables included in the model come from a range of sociodemographic and attitudinal variables. We use gender (with male as a reference category), age and education.

The first hypothesis, which is formulated based on the cognitive mobilisation theory, is tested by creating an index of EU knowledge. The utilitarian/economic approach (H2a, b and c) is tested through the inclusion of a question related to perceptions about the current household economic situation and another question on the prospective subjective evaluation of the national economy. Furthermore, in order to test whether socioeconomic placement of individuals reflects whether an individual is a winner or loser of European integration (H2c), we included some sociodemographic variables in the model. These are: ‘low education’ and ‘university education’ as dummies along with the occupational dummy variables for manual workers, managers and unemployed.

The national identity approach (H3) is tested with the introduction in the model of a variable of ‘national identity only’. Due to the absence of this question in the survey of 2009, we used as a proxy the question whether respondents feel they are EU citizens. In order to test the hypothesis of a possible association between an increased level of political distrust for the national government and euroscepticism (H4), the variable of trust in the national government is used. For testing H5, which is about the correlation between eurosceptic stances and negative evaluation of EU democracy, we introduced the variable of the (negative) evaluation of EU democracy. In order to test whether EU political efficacy is a determinant of euroscepticism (H6), we included the indicator ‘My voice does not count in the European Union’. Finally, the hypothesis related to the political/ideological approach is tested using the question of self-placement on the left-right axis. We created four dummy variables (extreme left, left, right and extreme right) with the centre being the reference category.

From pro-European to eurosceptic during the eurozone crisis? The evolution of public opinion towards the EU in Southern Europe, 2009–2018

Eurobarometer indicators reveal certain striking patterns. Overall, we can certainly say that the eurozone crisis has undermined the conventional wisdom – largely established prior to the crisis – concerning the region’s pro-European character. Starting with the question about the negative image of the EU, which is our dependent variable in the micro-level analysis below too, the distribution of the responses is presented in .

Figure 1. Negative image of the EU before, during and after the eurozone crisis: ‘Old Southern Europe’ and EU average (2009, 2014 and 2018)

Not surprisingly, the first main conclusion is that the most negative image of the EU is observed at the peak of the eurozone crisis in all four countries: ranging from 45 per cent in Greece and 30 per cent in Italy to 26 per cent in Portugal and 22 per cent in Spain. Before the onset of the crisis, the proportion who harboured a negative image of the EU was much lower in all four countries (ranging from 10 per cent in Italy to 19 per cent in Greece). From 2009 to 2014, negative stances increased by 26 per cent in Greece and by 10 per cent in Portugal.

In 2018, after the eurozone crisis, a decline in the negative EU image is observed in all four countries, but not to the same extent in all. On the one hand, only 13 per cent of Portuguese and 15 per cent of Spanish citizens had a negative image of the EU – percentages below the EU average (18 per cent). Interestingly, the results in Portugal were even lower than before the crisis. Therefore, it seems that especially in Portugal but also in Spain there was, in 2018, an overwhelming majority with a positive image of the EU. On the other hand, in Italy and especially in Greece, there was a significant group of citizens who still held negative views about the EU (25 per cent in Italy and 34 per cent in Greece, both above the EU average).

Overall, the main conclusion from is that even though the ups and downs in terms of the image of the EU follow the same patterns in the four countries, there are important differences. Possible explanations for this differentiation could be economic factors (the crisis in Greece was more severe and in 2018 the country was completing its third bailout programme), or the influence of an anti-European agenda endorsed by parties and the media specifically regarding the negative role of the EU in the crisis, as well as the dynamic presence of eurosceptic parties mainly in Greece and Italy.

A possible legitimacy crisis? Evaluation of EU democracy and trust in European institutions

During the period of the eurozone crisis a remarkably high percentage of South European citizens show a negative evaluation of the performance of EU democracy (see ). In total, 74 per cent of Greeks, 62 per cent of Italians and Spaniards and 69 per cent of Portuguese citizens negatively appraised democracy at the EU level (with the EU average at about 47 per cent). These findings contradict previous patterns of positive evaluations of EU democracy in these countries (in contrast to usually lower levels of positive evaluation of national democracies, e.g. Hobolt Citation2012, pp. 91–92) and could be linked to the profound disillusionment of citizens, especially at the peak of the crisis. Moreover, in Greece, this period gave rise to phenomena of civil unrest along with the rise of radicalism, extremism and populism (see among others Dinas et al. Citation2013). Additionally, particularly in Greece and Portugal, the attribution of blame for the crisis often pointed to EU policies and institutions. Nevertheless, as Kriesi (Citation2018) argues, the critical evaluation of democracy during the eurozone crisis did not undermine the citizens’ support for democracy. After the crisis period, we observe a sharp decline in negative evaluations of EU democracy in Italy and especially Spain and Portugal, and also but to a much lesser extent in Greece. The fact that Greece remains an outlier could be related to the depth of the economic crisis in the country.

Figure 2. Negative evaluations of EU democracy before, during and after the eurozone crisis: ‘Old Southern Europe’ and EU average (2009, 2014 and 2018)

The negative evaluation of EU democracy is accompanied by high levels of distrust of EU institutions and the EU itself (see ). In the pre-crisis period in Southern Europe there was a pattern of higher trust in the EU institutions compared to national ones. But at the peak of the crisis we observe a kind of ‘distrust syndrome’ directed towards EU institutions. In the eyes of the citizens the austerity measures and the ensuing recession were widely construed as externally imposed by EU institutions (especially the European Commission). The most negative stances towards EU institutions are recorded for the European Central Bank in all four countries, while the European Parliament still held the highest percentages of trust (although also in decline compared to the period before the onset of the crisis). In 2018 the data show that there was an increase in the levels of trust in Spain, Portugal but also in Greece for all EU institutions. On the contrary, in Italy levels of trust in the European Commission were even lower and the picture remained almost unchanged for the other institutions. This could be attributed to the immigration/refugee crisis and the electoral rise of the former Lega Nord, now known simply as Lega.

Figure 3. Trust in EU Institutions and in the EU: ‘Old Southern Europe’ 2009, 2014 and 2018 (% of total)

The main conclusion from the analysis at the aggregate level is that the most significant boost in eurosceptic stances took place in Greece. An increase in critical stances towards the EU can already be observed from the late 2000s (Teperoglou Citation2016). However, during the crisis, euroscepticism in this country exceeded even the levels of the traditionally eurosceptic UK (Verney Citation2015, p. 286). Portugal followed with particularly high levels of anti-European stances during the peak of the crisis compared to the pre-crisis period. In Italy, increased anti-European sentiment was already visible earlier, it intensified during the crisis and continues to be evident.

On the other hand, Spain showed the lowest level of euroscepticism during the crisis. Moreover, in post-crisis Spain and Portugal, a new pro-European equilibrium has emerged. We might conclude that the rise of euroscepticism in the two Iberian countries was more conjunctural and related to the eurozone crisis itself. On the other hand, the data show that in Italy and Greece euroscepticism had become more entrenched. There was a more critical evaluation of the European project as a whole, irrespective of the passing of the crisis. Finally, there were differences between the two bailout countries in the evolution of public support towards the EU at least at the aggregate level of analysis.

In order to better understand and interpret the trends observed at the aggregate level, in the next section we switch to the individual-level of analysis.

The determinants of euroscepticism in ‘Old’ Southern Europe

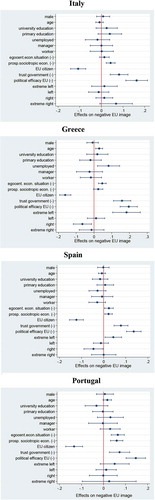

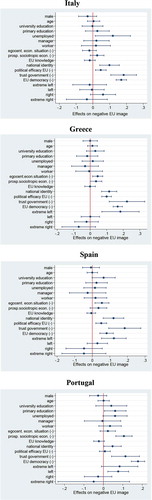

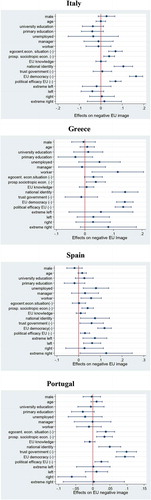

In order to test our hypotheses, we rely on the results of the ordered logit model presented in Tables A2 and A3 in the online Appendix. Moreover, we used the Brant test to explore whether the proportional odds/parallel lines assumptions of the ordered logit model are met. We find that this is the case for most of the regressions, with a few exceptions.Footnote8 ) present the marginal effects of our predictors of euroscepticism on the dependent variable (a negative EU image). These enable the reader to more easily examine the differences between countries and years.

Figure 4. (a) Predictors of Euroscepticism in ‘Old Southern’ Europe: Average marginal effects before the eurozone crisis (2009)

Figure 4. (b) Predictors of euroscepticism in ‘Old Southern Europe’: Average marginal effects at the peak of the eurozone crisis (2014)

Figure 4. (c) Predictors of euroscepticism in ‘Old Southern Europe’: Average marginal effects after the eurozone crisis (2014)

We begin by examining H1, in which we try to depict whether there is a correlation between low levels of EU knowledge and eurosceptic stances. The conclusion is that for 2014 and 2018 there is no evidence of such a link in any of the four countries (the question was not included in the survey of 2009). Thus, our hypothesis is not confirmed, meaning that citizens in southern Europe who were not well-informed about EU politics did not necessarily turn into eurosceptics.

Moving to the economic/instrumental approaches to explain EU public opinion variation (H2a, b and c) the results do not follow the same pattern in all four countries over the timeframe of our study. More specifically, in 2009, before the onset of the crisis, the prospective evaluation of the economic situation of the country (H2b) was an important determinant in Italy, Spain and Portugal, whereas it was less important in Greece. Interestingly, in the latter in 2009, egocentric economic utilitarianism related to employment status (H2c) was a significant determinant. The other variable which captures egocentric economic utilitarianism (evaluation of the household economic situation-H2a) was a significant predictor before the peak of the crisis in Greece, Spain and Portugal but not in Italy (see ) as well as Tables A2 and A3 in the online Appendix). Overall, we might conclude that even before the emergence of the eurozone crisis, the economic calculus explanation gains some support, whereas the deviations between the four countries could be justified by the different trajectories at the level of the national economy.

At the peak of the crisis in 2014, a different pattern is observed. As ) shows, unemployed status became significant as a determinant of euroscepticism in Italy but not any more in Greece. Moreover, in Greece both egocentric and sociotropic economic utilitarianism were important factors (confirming H2a and H2b); in Spain only the egocentric factor mattered and in Portugal only the sociotropic factor (and thus H2b is partially disconfirmed). On the other hand, in Italy economic considerations (with the exception of unemployment) did not seem to be associated with the increase in euroscepticism. In other words, (low) socio-economic status does not appear to be a significant factor in the countries that signed bailout agreements during the peak of the crisis, thus disconfirming our hypothesis. This could be attributed to the lack of significant variation among the samples, given that the effects of the crisis were severe for the majority of Greek and Portuguese society.

Moving to 2018, after the end of the eurozone crisis, the predictors associated with the utilitarian/economic approaches seem to be important determinants in Italy, as presented in . As the data at the aggregate level showed above, in 2018 the Italians recorded the most eurosceptic stances on various indicators compared to the citizens of the other three countries. On the other hand, in Spain only the (negative) prospective evaluation of the national economic situation emerged as an important predictor. For Greece and Portugal, the economic calculus considerations were important, confirming both H2a and H2b. Moreover, there is a correlation between low socio-economic status and an inclination to adopt more eurosceptic attitudes (low education for Portugal and being a worker in Greece). The increased significance of socioeconomic explanations in Greece and Portugal in this period could be interpreted as a sign of return to normality in terms of drivers of euroscepticism. This could reflect the ‘restoration’ of variance in the samples of the two populations in terms of economic evaluations (both egocentric and sociotropic).

Moving to the third hypothesis, the so-called cultural explanations of public support for the EU, the overarching conclusion is that the feeling of strong and exclusive national identity is one of the most significant predictors of euroscepticism in ‘Old Southern Europe’ throughout the period covered by our study. The loss of national sovereignty because of the imposition of economic measures by EU institutions and the IMF dominated party and broader political discourse at the peak of the crisis in all four countries. Therefore, our findings are in line with those of Serricchio, Tsakatika and Quaglia (Citation2013) who found national identity to be more important in explaining euroscepticism at the beginning of the crisis. This enduring characteristic downplayed the role of the economy as a predictor of euroscepticism, especially at the peak of the crisis.

Other significant determinants are the low levels of trust in each national government (H4) and the negative evaluation of EU democracy (H5). Our hypotheses are confirmed for all four countries at the peak of the eurozone crisis. However, the possible spill-over of dissatisfaction from national to EU institutions as an explanation for a surge in eurosceptic stances is also significant before the onset of the crisis (we do not have data for EU democracy). For 2018, the low level of trust in the national government was still relevant as a predictor in Spain and Portugal, but not in Italy and Greece, as presented in ). In the case of Greece, the more eurosceptic orientation of the coalition government, composed of the radical left party of SYRIZA (Συνασπισμός Ριζοσπαστικής Αριστεράς – Coalition of Radical Left) and the right-wing populist ANEL (Ανεξάρτητοι Έλληνες – Independent Greeks), that assumed office in 2015 can explain why lower trust in the government (most probably by sympathisers of the opposition parties) was associated with pro-European attitudes and vice versa. The same explanation might apply to Italy, given the change in government after the 2018 election when a coalition of M5S and The League took power.

Moving to other hypotheses, as expected before the onset of the crisis, the citizens who believed their voice did not count in the EU tended to adopt more eurosceptic stances, thus confirming our hypothesis (H6). At the peak of the crisis, low levels of EU-related political efficacy continued to play a salient role in Italy, Greece and Spain, but not in Portugal. After the crisis, this was again a significant predictor for all countries. Overall, the results are inconclusive regarding H6.

Finally, our analysis reveals some interesting patterns in the political/ideological approach of the determinants of euroscepticism. As shown by ) and by Table A3 in the online appendix, in Portugal at the peak of the crisis, self-placement on the centre-left and to a lesser extent on the extreme left was a significant determinant of eurosceptic stances. This could be attributed to the role of the centre-left PS (Partido Socialista – Socialist Party) in opposition and to the active voices of the two radical left-wing parties, the PCP (Partido Comunista Português – Portuguese Communist Party)Footnote9 and the BE (Bloco de Esquerda – Left Bloc) contesting the role of the EU during the crisis. These coefficients lost significance in 2018, which might be related to the fact the PS was then in government after a parliamentary agreement with the two radical left parties. On the other hand, in 2018, self-placement on the centre-right in Portugal significantly increased the likelihood of a pro-European stance. Meanwhile for Greece in both 2009 and 2014, placement on the extreme left of the ideological spectrum was an important determinant of euroscepticism. Interestingly, this loses significance in 2018, probably due to the detente by then reached between the radical left SYRIZA and European governments and institutions.

Moving to Spain, our hypothesis (H7) concerning the more likely adoption of eurosceptic stances by left-wing citizens is fully confirmed for all three years. Moreover, in 2018, those who were still eurosceptic in Spain came from the left (extreme and centre) but also from the extreme right (thus disconfirming H7). Here our findings fit with the rise of the extreme right-wing party, Vox, which entered Parliament after the 2019 national elections. Finally, for Italy, unlike the other three countries, the data show self-placement on the left-right axis is not an important determinant, except for the extreme right in the pre-crisis period (confirming H7). Overall, our findings are in line with earlier work on the importance of party system legacies and national contexts when discussing varieties of euroscepticism (Lisi & Tsatsanis Citation2018).

Conclusions

The main aim of this article was to provide an overview of the rise of euroscepticism among citizens in ‘Old Southern Europe’ and try to explain the determinants of these attitudes. The main research question is whether in Italy, Greece, Spain and Portugal the heightened anti-European stances during the eurozone crisis were more conjunctural or more structural and deep-rooted. We also aimed to analyse the micro-level factors that underpinned (or impeded) the adoption of eurosceptic attitudes and how these factors evolved from 2009 to 2018.

Our findings are strong and positive regarding the connection between anti-European stances and national identity in all four countries and for the entire timeframe of our study. This pattern demonstrates that at least in Southern Europe, exclusive national identity diminishes support for European integration, as Hooghe and Marks (Citation2005) pointed out for other EU member states. Therefore, even in times of extraordinary economic recession this factor continues to explain a significant part of the variation in public opinion support for the EU. Another conclusion is that – counterintuitively – the economic calculus approach does not have the same discriminatory power when it comes to euroscepticism. However, as we showed above, there is no common trend among the countries of our study when it comes to the importance of economic factors.

Furthermore, the increase in euroscepticism in the region is undoubtedly linked to the deterioration in economic conditions. However, the relative lack of variation in terms of perceptions of economic trajectories (both personal and national) impede the overall explanatory power of economic considerations, particularly during the peak of the economic crisis. We might conclude that cultural and political/institutional approaches tend to more closely explain southern European euroscepticism before, during and after the crisis than economic considerations. On the other hand, ideological preferences are important predictors in Greece, Portugal and Spain especially for those imbued with a leftist ideology (confirming the continuing influence of party and ideological legacies in the three countries) whereas in Italy this is not the case.

Overall, one could argue that both aggregate and micro-level data reveal more differences than similarities among the four Southern European countries when it comes to attitudes towards Europe. Euroscepticism for the two countries of the Iberian Peninsula appears to be more ephemeral; after the eurozone crisis, particularly in Spain, there has been a return to a new equilibrium where positive stances towards the European project outnumber negative feelings. In Greece euroscepticism is more persistent, possibly because the crisis here was more severe than in the other countries and its effects run deeper. The findings are more ambiguous for Italy. The country follows a different trajectory and there were signs of increasing euroscepticism in 2018.

If we posit the question whether Southern Europe returned to normality after the crisis in terms of its stances towards the EU, the answer is affirmative for Spain and Portugal, but not for Greece (yet) and not for Italy either. Therefore, the crisis does not seem to have had a homogenous effect on the euroscepticism of ‘Old Southern Europe’ countries. It was smoother for Portugal and Spain, which returned to a pre-crisis positive image of the EU after the crisis had passed. It left a stronger mark on Greece and Italy, consolidating eurosceptic attitudes in an apparently more structural way. However, it would be premature to give any definitive answers given the unpredictability and contingency of European politics at the moment. Although the eurozone crisis is generally considered to have been overcome, with social and economic indicators getting back to their pre-crisis levels, the eurozone saga continues. Not only could this crisis have generated lasting effects that predispose individuals in south European countries to be sceptical about the EU, but other crises might also be looming, given the evident vulnerabilities of south European economies. The rift between the southern and northern countries of the Eurozone over the economic response to the coronavirus crisis confirms that the legacy of the sovereign debt and migration crises has been the sedimentation of a north-south divide that could keep resurfacing every time the Eurozone faces a new challenge.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (361.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for the useful comments as well as the editor, Susannah Verney for the insightful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eftichia Teperoglou

Eftichia Teperoglou is Assistant Professor at Aristotle University, Thessaloniki. Her main research interests are in the fields of political and electoral behaviour, comparative politics and public opinion. She has published in peer-reviewed journals and in edited volumes. Her main publications include the monograph Οι Άλλες «Εθνικές» Εκλογές: Η Ιστορία των Ευρωεκλογών στην Ελλάδα 1981–2014 (The Other ‘National’ Elections. Analysis of the European Elections in Greece 1981–2014 (Papazisis, 2016) and The 2014 European Parliament Elections in Southern Europe: Still Second-Order or Critical Contests? (co-edited with Hermann Schmitt) (Routledge ‘South European Society and Politics’ book series, 2018).

Ana Maria Belchior

Ana Maria Belchior is an associate professor at ISCTE-IUL (Instituto Universitário de Lisboa) in Lisbon, and a researcher at CIES-IUL. She has been involved in several projects related to the themes of democracy and globalisation, political participation, democratic representation, political congruence, electoral pledges and decision-making. Her work has been published in edited volumes and peer-reviewed journals such as Comparative Political Studies, International Political Science Review, Party Politics, Comparative European Politics, Political Studies, among others.

Notes

1. Previous research either found no impact of the global financial crisis on euroscepticism (Serricchio, Tsakatika & Quaglia Citation2013), or a stronger impact of the eurozone crisis when compared to the global crisis (Braun & Tausendpfund Citation2014). Our option is thus to focus our study on the eurozone crisis and not the global financial crisis.

2. The term ‘Old Southern Europe’ refers to the group of southern European countries that joined the EU up to 1986 (Italy, Greece, Portugal and Spain), contrasting with the ‘New Southern Europe’, referring to those that only joined in 2004 (Malta and Cyprus).

3. Greece signed the first MoU in May 2010 (under the government of the socialist party, PASOK [Πανελλήνιο Σοσιαλιστικό Κίνημα- Panhellenic Socialist Movement]), while the second was activated in March 2012 and implemented by the coalition government of PASOK and the centre-right ND (Νέα Δημοκρατία – New Democracy). The third bailout package was signed in July 2015 by the coalition government of the radical left party, SYRIZA, with the populist radical right party, Independent Greeks. This package ended on 20 August 2018. The Portuguese MoU was signed in June 2011, by a majority centre-right coalition, which took over after the minority socialist government of José Sócrates resigned in March 2011, unable to implement a package of austerity measures to deal with the external debt and market pressure. The bailout programme in Portugal ended in 2014. The Spanish MoU was signed in July 2012 under a majority government of the Spanish conservative party (PP) and ended in 2013. In the case of Spain, the agreement specifically concerned the financial sector, aimed at rescuing Spanish banks.

4. In our article we focus on these four countries and decided not to include Cyprus – a country also affected by the eurozone crisis, where a decline in pro-European stances too is also observed. The main reason is that the pre-crisis Europhile image of Southern Europe refers to the ‘Old South European’ countries. As Verney (Citation2018) points out, in the ‘new’ Southern Europe there was already greater contestation of the EU than in the ‘Old Southern Europe’.

5. According to the World Bank, unemployment reached its peak in 2013 or 2014 in the four countries (the figures for 2009, 2014 and 2018 are: in Greece 9.6 per cent, 26.5 per cent and 19.2 per cent; in Portugal 9.4 per cent, 14.0 per cent and 6.9 per cent; in Spain 17.9 per cent, 24.4 per cent and 15.5 per cent; and in Italy: 7.7 per cent, 12.7 per cent and 10.2 per cent). Data from Eurostat on general government gross debt also shows a peak in 2014. Regarding median income (EU-SILC and ECHIP surveys) the data are also illustrative: back in 2009, it is 12,626 euros in Greece, 15,564 in Spain, 9,407 in Portugal and 15,233 in Italy. In 2014 this has fallen, especially in Greece (8,674), while standing at 14,195 in Spain. In contrast, Portugal and Italy show a modest increase (10,125 in Portugal and 15,254 in Italy). Finally, all countries show an increase in 2018.

6. These are: EB71.3 (June-July 2009), EB 82.3 (November 2014) and Eurobarometer 90.3 (November 2018).

7. Another reason for selecting this variable is the relatively low percentage of missing values (e.g. in 2018 ‘Do not know’ is 1.87 per cent in Italy, 0.45 per cent in Greece, 1.13 per cent in Spain and 1.65 per cent in Portugal).

8. The exceptions are: the Portuguese survey of 2009 and the two Italian surveys of 2014 and 2019. We added the detail option to the brant command in order to see which variables are responsible for the violation of these assumptions. The coefficients which differ greatly are, for the Portuguese survey in 2009, the extreme right and for both Italian surveys the variables of extreme left and extreme right. The differentiation might be caused by the high percentages of neutral positions in the EU image among those who place themselves at the extreme right in Portugal before the onset of the crisis and at the extreme right and left in 2014 and 2018 in Italy. For Portugal, the eurozone crisis might have politicised the issue of Europe for extreme right citizens. For Italy the pattern is less clear. But, in both cases once we remove these ideological dummies from the model, the Brant test chi2 is significant.

9. The PCP contests elections in coalition with the Greens, as the CDU (Coligação Democrática Unitária – Unitary Democratic Coalition).

References

- Anderson, C. J. (1998) ‘When in doubt, use proxies: attitudes toward domestic politics and support for European integration’, Comparative Political Studies, vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 569–601.

- Andreadis, I., Poletti, M., Teperoglou, E. & Vezzoni, C. (2014) ‘Economic crisis and attitudes towards the European Union: are Italians and Greeks becoming eurosceptic because of the crisis?’, paper presented at the 64th Annual International Conference of the Political Science Association, Manchester, 14–16 April.

- Armingeon, K. & Ceka, B. (2014) ‘The loss of trust in the European Union during the Great Recession since 2007: the role of heuristics from the national political system’, European Union Politics, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 82–107.

- Belchior, A. M., (2015) Confiança Nas Instituições Políticas [Trust in the Political Institutions], Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos, Lisbon.

- Boomgaarden, H., Schuck, A., Elenbaas, M. & de Vreese, D. (2011) ‘Mapping EU attitudes: conceptual and empirical dimensions of euroscepticism and EU support’, European Union Politics, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 241–266.

- Braun, D. & Tausendpfund, M. (2014) ‘The impact of the euro crisis on citizens’ support for the European Union’, Journal of European Integration, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 231–245.

- Carey, S. (2002) ‘Undivided loyalty: is national identity an obstacle to European integration?’, European Union Politics, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 387–413.

- Clements, B., Nanou, K. & Verney, S. (2014) ‘We no longer love you, but we don’t want to leave you’: the Eurozone crisis and popular euroscepticism in Greece’, Journal of European Integration, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 247–266.

- Dinas, E., Georgiadou, V., Konstantinidis, I. & Rori, L. (2013) ‘From dusk to dawn. Local party organisation and party success of right-wing extremism’, Party Politics, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 80–92.

- Down, I. & Wilson, C. J. (2008) ‘From ‘permissive consensus’ to ‘constraining dissensus’: A polarizing union?’, Acta Politica, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 26–49.

- Eichenberg, R. & Dalton, R. J. (1993) ‘Europeans and the European Community: the dynamics of public support for European integration’, International Organization, vol. 47, no. 4, pp. 507–534.

- Eichenberg, R. C. & Dalton, R. J. (2007) ‘Post-Maastricht blues: the transformation of citizen support for European integration’, Acta Politica, vol. 42, nos. 2–3, pp. 128–152.

- Freire, A., Teperoglou, E. & Moury, C. (2014) ‘Awakening the sleeping giant in Greece and Portugal? Elites’ and voters’ attitudes towards EU integration in difficult economic times’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 477–499.

- Gabel, M. (1998) ‘Public support for European integration: an empirical test of five theories’, The Journal of Politics, vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 333–354.

- Gabel, M. & Palmer, H. (1995) ‘Understanding variation in public support for European integration’, European Journal of Political Research, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 3–19.

- Hobolt, S. B. (2012) ‘Citizen satisfaction with democracy in the European Union’, Journal of Common Market Studies, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 88–105.

- Hobolt, S. B. & Wratil, C. (2015) ‘Public opinion and the crisis: the dynamics of support for the euro’, Journal of European Policy, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 238–256.

- Hooghe, L. & Marks, G. (2005) ‘Calculation, community and cues, public opinion on European integration’, European Union Politics, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 419–443.

- Hooghe, L. & Marks, G. (2007) ‘Sources of euroscepticism’, Acta Politica, vol. 42, nos. 2–3, pp. 111–127.

- Hooghe, L. & Marks, G. (2009) ‘A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: from permissive consensus to constraining dissensus’, British Journal of Political Science, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 1–23.

- Hooghe, L. & Marks, G. (2018) ‘Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage’, Journal of European Public Policy, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 109–135.

- Hutter, S. & Grande, E. (2014) ‘‘Politicizing Europe in the national electoral arena: A comparative analysis of five West European countries, 1970–2010ʹ’, Journal of Common Market Studies, vol. 52, no. 5, pp. 1002–1018.

- Inglehart, R. (1970) ‘Cognitive mobilization and European identity’, Comparative Politics, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 45–70.

- Inglehart, R., Rabier, J.-R. & Reif, K. (1991) ‘The evolution of public attitudes toward European integration: 1970–1986’, in Eurobarometer: The Dynamics of European Public Opinion, eds K. Reif & R. Inglehart, Macmillan, London, pp. 111–131.

- Janssen, J. I. (1991) ‘Postmaterialism, cognitive mobilization and public support for European integration’, British Journal of Political Science, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 443–468.

- Jiménez, A. M. & de Haro, A. E. (2011) ‘Spain: euroscepticism in a pro-European country?’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 105–131.

- Kriesi, H. (2018) ‘The implications of the euro crisis for democracy’, Journal of European Public Policy, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 59–82.

- Lisi, M. & Tsatsanis, E. (2018) ‘Against Europe? Untangling the links between ideology and euroscepticism’, paper presented at the 76th MPSA Conference, Chicago, USA, 5–8 April.

- Llamazares, I. & Gramacho, W. (2007) ‘Eurosceptics among euroenthusiasts: an analysis of Southern European public opinions’, Acta Politica, vol. 42, nos. 2–3, pp. 211–232.

- Lubbers, M. & Scheepers, P. (2005) ‘Political versus instrumental euro-scepticism: mapping scepticism in European countries and regions’, European Union Politics, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 223–242.

- Mcevoy, C. (2016) ‘The role of political efficacy on public opinion in the European Union’, Journal of Commons Market Studies, vol. 54, no. 5, pp. 1159–1174.

- McLaren, L. (2007) ‘Explaining mass-level euroscepticism: identity, interests, and institutional distrust’, Acta Politica, vol. 42, nos. 2–3, pp. 33–251.

- Orriols, L. & Cordero, G. (2016) ‘The breakdown of the Spanish two-party system: the upsurge of Podemos and Ciudadanos in the 2015 general election’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 469–492.

- Sánchez-Cuenca, I. (2000) ‘The political basis of support for European Integration’, European Union Politics, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 147–171.

- Schäfer, C., Braun, D., Popa, S. & Schmitt, H. (2020). ‘The reshaping of political conflict over Europe: from pre-Maastricht to post-‘Euro crisis’, West European Politics, doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1709754.

- Schmitt, H. & Teperoglou, E. (2015) ‘The 2014 European Parliament Elections in Southern Europe: second-order or critical elections?’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 287–309.

- Serricchio, F. (2012) ‘Italian citizens and Europe: explaining the growth of euroscepticism’, Bulletin of Italian Politics, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 115–134.

- Serricchio, F., Tsakatika, M. & Quaglia, L. (2013) ‘Euroscepticism and the global financial crisis’, Journal of Common Market Studies, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 51–64.

- Taggart, P. (1998) ‘A touchstone of dissent: euroscepticism in contemporary Western European party systems’, European Journal of Political Research, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 363–388.

- Teperoglou, E. (2016) Οι ‘Αλλες’ Εθνικές Εκλογές. Αναλύοντας τις Ευρωεκλογές στην Ελλάδα 1981–2014 [The Other ‘National’ Elections. Analysis of the European Elections in Greece 1981–2014], Papazisis Publications, Athens.

- Teperoglou, E., Freire, A., Andreadis, I. & Viegas, J. M. L. (2014) ‘Elites’ and voters’ attitudes towards austerity policies and their consequences in Greece and Portugal’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 457–476.

- Teperoglou, E. & Tsatsanis, E. (2014) ‘Dealignment, de-legitimation and the implosion of the two-party system in Greece: the earthquake election of 6 May 2012’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion, & Parties, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 222–242.

- Tsatsanis, E. & Teperoglou, E. (2016) ‘Realignment under stress: the July 2015 referendum and the September parliamentary election in Greece’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 427–450.

- Van Elsas, E., Hakhverdian, A. & Van der Brug, W. (2016) ‘United against a common foe? The nature and origins of euroscepticism among left-wing and right-wing voters’, West European Politics, vol. 39, no. 6, pp. 1181–1204.

- Van Elsas, E. J. & Van der Brug, W. (2015) ‘The changing relationship between left-right ideology and euroscepticism, 1973–2010’, European Union Politics, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 194–215.

- Verney, S. (2011) ‘Euroscepticism in Southern Europe: A diachronic perspective’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1–29.

- Verney, S. (2014) ‘Broken and can’t be fixed: the impact of the economic crisis on the Greek party system’, The International Spectator: Italian Journal of International Affairs, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 18–35.

- Verney, S. (2015) ‘Waking the ‘sleeping giant’ or expressing domestic dissent? Mainstreaming euroscepticism in crisis-stricken Greece’, International Political Science Review, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 279–295.

- Verney, S. (2018) ‘Losing loyalty: the rise of polity euroscepticism in Southern Europe’, in The Routledge Handbook of Euroscepticism, eds B. Leruth, N. Startin & S. Usherwood, Routledge, London & New York, pp. 168–186.