ABSTRACT

This is an introductory article for a special issue on affective polarisation in Spain. After discussing the concept and its operationalisation in multi-party settings, we offer data on affective polarisation in Spain and Southern Europe from a comparative perspective using the Comparative National Election Project (CNEP) and Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES). In the second part, we pay special attention to the Spanish case, analysing different dimensions of affective polarisation and its evolution overtime, by taking advantage of an extensive number of indicators from the E-DEM panel survey. Finally, we describe its relationship with ideological polarisation and analyse its possible multidimensional nature. We conclude by introducing the rest of contributions of this special issue.

Ideological discrepancies between parties and their supporters provide the basis for the emergence of political cleavages and, in turn, voter alignments that define party systems (Bartolini & Mair Citation1990; Franklin, Mackie & Valen Citation1992; Lipset & Rokkan Citation1967). Nevertheless, scholars have increasingly noticed the emergence of a distinct process driving democratic competition referred to as affective polarisation (Hetherington Citation2009; Hetherington, Long & Rudolph Citation2016; McCoy, Rahman & Somer Citation2018; Iyengar et al. Citation2019). Iyengar and his colleagues (Iyengar, Sood & Lelkes Citation2012; Iyengar & Westwood Citation2015) conceptualise this phenomenon as an emotional attachment to in-group partisans and hostility towards out-group partisans. This process goes beyond classic ideological polarisation, in the sense that an increase in inter-partisan hostilities may not be reflected in higher levels of ideological disagreements among citizens and may have more devastating consequences (McCoy & Somer Citation2019; Lauka, McCoy & Firat Citation2018; Reiljan Citation2020; Sides, Tesler & Vavreck Citation2018; Somer & McCoy Citation2018a, Citation2018b). Moreover, affective polarisation can arise from other non-partisan identities that divide the world into in-groups and out-groups, such as religion or ethnicity (Hobolt, Leeper & Tilley Citation2020; Westwood et al. Citation2018).

The study of affective polarisation constitutes a necessity since it could be responsible for many contemporary ills of democratic functioning (MacKuen et al. Citation2010; McCoy & Somer Citation2019; McCoy, Rahman & Somer Citation2018; Somer & McCoy Citation2018b), and a potential cause behind the support for new illiberal parties, which increases the chances of democratic backsliding (Levitsky & Ziblatt Citation2018; McCoy, Rahman & Somer Citation2018; Svolik Citation2019).

While this topic has been primarily studied in the United States (US), affective polarisation has increasingly received comparative attention from European scholars in an attempt to study this phenomenon in multi-party settings, making important contributions, especially on its measurement (Gidron, Adams & Horne Citation2020; Harteveld Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Hobolt, Leeper & Tilley Citation2020; McCoy Citation2019; Reiljan Citation2020; Somer & McCoy Citation2018b; Ward & Tavits Citation2019; Wagner Citation2020). However, knowledge of affective polarisation in broader comparative terms is still limited, especially when it comes to its driving forces and its potential behavioural and attitudinal consequences. The study of affective polarisation is even more imperative in Southern Europe, a region of the world that counts with three of the countries (Spain, followed by Portugal and Greece) that, according to Gidron, Adams and Horne (Citation2020, pp. 36–37), register some of the highest levels of affective polarisation and the significant appearance of new radical parties in a context of increasing party fragmentation and electoral volatility. Thus, in the following pages and this special issue we will try to address its study in this region, paying special attention to the Spanish case, which is characterised by its high levels together with an increasingly fragmented party system in which new radical left-wing (Podemos, We can) and right-wing (Vox) parties has successfully emerged to the electoral arena during the last decade.

In this introductory article, we will describe the levels of affective polarisation in relevant countries in the region and the relations of this phenomenon with ideological polarisation. Specifically, we focus on the Spanish case and its relationship with these new radical left-wing and right-wing parties. This descriptive analysis will show that, in contrast to Gidron, Adams and Horne’s (Citation2020) initial assessment, Southern Europe does not appear to exhibit higher mean levels of affective polarisation, compared to other world regions, although some specific countries/elections in this region are among the most polarised cases. This article is not limited to the basic descriptions, but it also shows that affective polarisation is a multidimensional phenomenon in which ‘politised’ social divisions are not yet completely aligned (sorted) with the dominant national partisan and ideological conflicts. For instance, the Spanish territorial cleavage, particularly the Catalan conflict, is also articulated by in- and out-group identities that constitute an increasingly related but different dimension from the partisan and ideological identities present at the national level. Furthermore, we provide evidence that partisan affective polarisation and ideological polarisation are two distinct but related concepts (Reiljan Citation2020; Rogowski & Sutherland Citation2016), i.e. individual time variation on affective polarisation is significantly explained by individual ideological polarisation. Finally, we also display evidence that the relationship between the former and extreme positions on concrete issues appears to be weaker or non-significant, which suggests that affective polarisation is mainly related to the identity component of ideology.

To discuss all of this we are going to use data from the Comparative National Election Project (CNEP) and the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) for the comparative part. The rest of this article relies on different surveys in Spain, especially on a unique panel dataset (E-DEM) collected in this country between 2018 and 2019 (Torcal et al. Citation2020).

Affective polarisation, ideology and non-partisan identities

The concept of affective polarisation is rooted in social identity theory (e.g. Huddy Citation2001; Tajfel & Turner Citation1979). Specifically, when individuals identify with a particular group in a competitive environment, they are motivated to positively distinguish the group from others, leading to in-group bias. That is, to the extent that partisanship constitutes an enduring social identity (Huddy, Mason & Aarøe Citation2015), the mere act of identifying with a party leads to affective attachments towards the members of their own party and negative feelings towards the members of the opposing parties (Iyengar, Sood & Lelkes Citation2012; Iyengar & Westwood Citation2015).

Although affective polarisation generally refers to sentiments towards partisans, most studies measure this phenomenon using evaluations of political parties/leaders, which are the two most frequent indicators included in the comparative surveys. However, the specific mechanisms driving affective polarisation may differ depending on the evaluated political objects (Kingzette Citation2021). Druckman and Levendusky (Citation2019), in the U.S. context, reveal that individuals tend to have more positive feelings towards supporters of the opposing party than towards the opposing party itself or its leader. Hence, affective polarisation measures using feelings about parties/leaders may overestimate the levels of hostility between partisans. In addition, a recent comparative study conducted by Reiljan et al. (Citation2021) shows that aggregate measures of affective polarisation regarding leaders tend to be lower than those regarding parties in parliamentary and multi-party systems. Given these measurement problems using different indicators, in this introductory article, we employ indistinctively feelings scales towards parties, their leaders and their voters (when possible).

Conceptually, affective polarisation differs from ideological polarisation. While the former focuses on the emotional responses of individuals towards other parties and their elites/supporters, the latter refers to the extent to which political elites (or the mass public) disagree on policy-issues or ideological positions along the left–right dimension. Part of the literature argues that both types of polarisation are weakly related and that affective polarisation is mainly the product of partisan identities and the alignment of other social identities along party lines ('social sorting') (e.g. Iyengar, Sood & Lelkes Citation2012; Iyengar & Westwood Citation2015; Mason Citation2018a). Conversely, other scholars provide evidence that ideological polarisation constitutes one of the main drivers of the polarisation of feelings about partisans.

Meanwhile, ideological differences between parties and candidates fuel affective polarisation because the stakes associated with vote choice increase as well as the tendency of citizens to use motivated reasoning to support their preferred electoral option (e.g. Rogowski & Sutherland Citation2016; Webster & Abramowitz Citation2017). Moreover, some scholars find that affective polarisation leads individuals to perceive that the party supply is more ideologically polarised than it appears (e.g. Ward & Tavits Citation2019). The adoption of extreme ideological positions and the alignment of multiple policy-issue attitudes along the ideological spectrum also feed affective polarisation (e.g. Bougher Citation2017; Wagner Citation2020), although some researchers find that these effects are quite weak (e.g. Lelkes Citation2018).

Some types of policy-issues may polarise feelings about parties and their supporters to a greater degree than others. Specifically, different studies find that socio-cultural issues (such as immigration) fuel affective polarisation more than socio-economic ones (Gidron, Adams & Horne Citation2020; Harteveld Citation2021a). Furthermore, ideology can refer to a social and political identity that is not necessarily rooted in a coherent set of opinions on policy-issues. Some scholars provide evidence that affective polarisation is primarily associated with identity-based ideology, rather than issue-based ideology, which is in line with the argument that affective polarisation is mainly produced by ideological and other social identities increasingly sorted along partisan lines (and not so much by divergences on policy issues) (Mason Citation2018b). In an important part of this article, we explore the relationship between affective and ideological polarisation in the Spanish case.

In addition, affective polarisation could be a multidimensional concept (Criado et al. Citation2015, Citation2018; Harteveld Citation2021b, p. 18; Lauka, McCoy & Firat Citation2018, p. 122), meaning that it might reflect other identities that are also political activated aside the partisan ones (Rudolph & Hetherington Citation2021). Affective polarisation could be driven by national/subnational identities, which some scholars have denominated as one of the most important formative rifts for affective polarisation (McCoy Citation2019, p. 27; Somer & McCoy Citation2018b, pp. 15–16) (for a recent contribution regarding the Catalan case, see Balcells, Fernández-Albertos & Kuo Citation2021). This could also be the case with other identity conflicts emerging from immigration and its affiliated intercultural challenges (Hobolt, Leeper & Tilley Citation2020). Therefore, affective polarisation could also be based on other conflicts and identities that are not fully aligned with partisan identities and the classic left-right ideological divide.

This discussion goes beyond the relationship between ideological and affective polarisation, especially because this relationship might be increasingly muddled as new conflicts – that go beyond the traditional left and right axis of competition – emerge and become salient, resulting in an important alternative source of polarisation in many European countries (Hooghe & Marks Citation2018; Kriesi et al. Citation2012; Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2015). Thus, affective polarisation could be a multidimensional phenomenon that results from the presence or emergence of overlapping conflicts and the in-group/out-group identities it produces. This is for instance, what Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley (Citation2020) have argued for the Brexit conflict in the United Kingdom.

Measurement of affective polarisation

The comparative measures

Our comparative analysis draws mostly on the CNEP and to a lesser degree on the CSES. The CNEP contains 57 elections across 27 countries between 1992 and 2020, including 15 cases involving multiple elections within the same country.Footnote1 Unfortunately, the comparable measures of affective polarisation are only fully available for 48 country/elections. In the CNEP dataset, measurement is only based on respondents’ likes/dislikes of party leaders. The CSES dataset includes both leaders and parties, although not for all country/elections. All these are 11-point scales ranging from dislike to like.

We have calculated partisan affective polarisation using the formula proposed by Wagner (Citation2020, pp. 3–5) for multi-party systems. Specifically, affective polarisation is measured as the extent to which the respondent’s affect is spread across the various relevant leaders (or parties) in a given party system, weighting each leader (or party) by its size (normalised proportion of votes received in current national elections) (see sections B and F of the online Appendix (available at https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2022.2044236) for more details about this measure). This measure recognises that there are individuals who, despite not being identified with any party (something quite frequent and growing in many democracies), may nevertheless hold sentiments towards political and partisan groups, so that it takes into account all respondents who express feelings of like-dislike towards leaders (or parties). Moreover, as Wagner (Citation2020) argues, this measure also acknowledges that some individuals do not express sympathy only towards a particular party, but towards different parties that are relatively close to each other in ideological terms; hence, this index better captures the opposition between blocs of parties than between single parties, something relevant in multi-party settings. Recent studies exploring affective polarisation in multi-party systems have used this spread-of-scores polarisation index (e.g. Harteveld Citation2021b; Hernández, Anduiza & Rico Citation2021).

Additionally, we have also calculated the aggregate measure proposed by Reiljan (Citation2020) using feelings about leaders. This index indicates the average divergence of respondents’ affective evaluations between the in-leader and the out-leaders, weighted by the electoral size of the parties of the leaders. This measure is preferable if the focus is on exclusive partisan identities. However, it reduces the number of considered individuals in countries where party identification is low (Thomassen & Rosema Citation2009), even though it constitutes a salient social identity (Huddy, Bankert & Davies Citation2018; Bankert, Huddy & Rosema Citation2017). This operationalisation is also problematic in multi-party settings with increasing levels of electoral volatility and number of independent voters. Following Wagner (Citation2020, p. 5), we have addressed some of these limitations by defining in-groups not based on party identification, but on the most-liked leader; in this way, we also take into account those individuals who, despite declaring no identification with any party, express more sympathy towards a particular party leader (see sections D and F of the online Appendix for more details about this index).

Measurements for the Spanish case

Our Spanish data derive from the E-DEM dataset (Torcal et al. Citation2020), which is comprised of a four-wave online panel survey of the Spanish voting age population conducted between October 2018 and May 2019Footnote2 (for details, see Table A1 in section A of the online Appendix). This period of time covers some key political moments in the recent evolution of Spanish politics.

We have also reproduced the same formula proposed by Wagner (Citation2020) using feelings scales for the leaders of the five national political parties and the three most important Catalan and Basque regional parties: Spanish Socialist Workers Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español-PSOE), Popular Party (Partido Popular-PP), Citizens (Ciudadanos-Cs), United We Can (Unidas Podemos-UP), Vox, Republican Left of Catalonia (Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya-ERC), Together for Catalonia (Junts per Catalunya-JxCAT), and Nationalist Basque Party (Partido Nacionalista Vasco-PNV). These feelings scales have been rescaled to range from 0 to 10. Furthermore, this dataset can create the same indices of polarisation but with two other partisan indicators based on the same formula and logic: feelings towards the same parties (although this was not included in the first two waves of the study) and feelings towards parties’ voters (although this index only includes the five national parties). This way we have three partisan-based indices of polarisation: parties, voters and leaders (for details, see sections B and F of the online Appendix).

Finally, the E-DEM dataset contains feelings and trust scales towards different territorial groups in Spain: Catalans, Basques, Madrileans and Andalusians. These last two are used together as the reference for Spanish identifiers. We have also rescaled and summed up the two items (feelings and trust) and divided the resulting scale by 2, which ranges from 0 to 10. From these scales, we built different territorial affective polarisation indices.Footnote3 First, there is the index that captures how much an individual (on average) likes/dislikes other territorial groups, compared to his/her own group (i.e. the mean distance in sentiments from the respondents’ own territorial group). Second, the same index is used for two pairs of groups: Catalans vs. others, and Basques vs. others. These indices range from −10 to 10. In this case, positive values mean that the respondents have more positive sentiments towards their in-territorial group than to the out-territorial groups; negative values refer to the opposite; and 0 means that the respondents have the same sentiments towards the in- and out-territorial groups (for the details of these indices, see section B of the online Appendix).

About ideological polarisation

These datasets contain questions measuring ideological polarisation departing from the self and party allocation on the left–right scale and use the standard formula for perceived ideological polarisation. This measure, which departs from the classic treatment by Hazan (Citation1995), is based on summing how the respondent positions each party compared to her/his average ideological positioning of all parties (Alvarez & Nagler Citation2004, p. 50; Ezrow Citation2007, p. 186; Wagner Citation2020, pp. 7–8). This is the most accepted measurement of ideological polarisation in the comparative literature (e.g. Curini & Hino Citation2012; Lupu Citation2015). We have also computed a measure of ideological extremism based on the spatial distance from the average position (for more details, see sections C and F of the online Appendix).

Affective polarisation from a comparative perspective

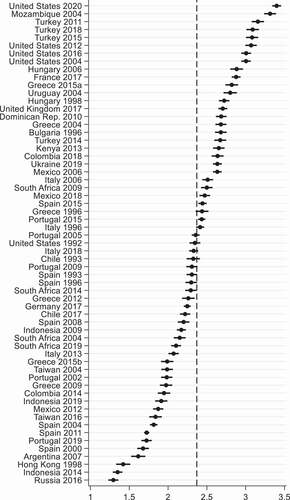

displays the average levels of the spread-of-scores affective polarisation index based on leaders thermometer feelings (WAPSL) for the 48 country/elections of the CNEP dataset, but including also the ones computed from the CSES dataset for the Southern European countries. Thus, this figure contains information on affective polarisation for 61 country/elections. In the online Appendix, we also report the affective polarisation regarding parties for the available Southern European country/elections in the CSES dataset, as well as the aggregate measure of affective polarisation based on Reiljan’s formula (Citation2020) (see Table A2).Footnote4

Figure 1. Comparative levels of affective polarisation regarding leaders (WAPSL), country/election means.Sources: CNEP and CSES.Notes: 95 per cent confidence intervals. The dashed line indicates the average level of affective polarisation.

Countries’ polarisation mean scores range widely from very low polarisation in Russia 2016 and Indonesia 2014 to high levels in Turkey (2011, 2015 and 2018 legislative elections), Mozambique 2004 and the US (2004, 2012, 2016 and 2020). The mean scores obtained by the recent presidential elections in the US, therefore, confirm the widespread recognition of its high levels of affective polarisation (e.g. Hetherington Citation2009; McCarty, Poole & Rosenthal Citation2006; Iyengar et al. Citation2019). Mozambique experienced a 15-year civil war from 1977 to 1992 and continuing tension between the parties of its rival combatants after a return to democratic elections.Footnote5 Regarding Turkey, other studies have already signalled that the country has become one of the most polarised around the globe under the Justice and Development and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan government (e.g. Somer Citation2019).

Among the most important European cases, we observe in this table the highest levels of affective polarisation regarding leaders in Hungary (2006, 1998), France (2017), Greece (2015, first election), United Kingdom (2017), and, as mentioned, Turkey (2011, 2015, 2018). Countries in other parts of the world have high levels of polarisation such as Uruguay (2004), the Dominican Republic (2010), Kenya (2013), Colombia (2018) and Mexico (2006). Overall, there does not appear to be a significant pattern in affective polarisation by regions from these data.

Regarding South European countries, Turkey (2011, 2015, 2018 and, to a lesser extent, 2014) as well as Greece (2015 first election and, to a minor degree, 2004) seem to be among the most polarised cases in the dataset. Interestingly, the most recent election in Spain (2015) included in this dataset also seems to display remarkably high levels of polarisation regarding leaders. Concerning Portugal, the election held in 2015 also registers polarisation levels slightly above the average of the selected country/elections, although the rest of elections exhibit lower polarisation levels, being the most recent one (2019) among the less polarised in the dataset. Italy also shows above average affective polarisation levels for the 2006 election, while the 1996 and the most recent 2018 elections are around the average. Other country/elections from the region are located below the mean, some with quite small levels of polarisation (see Spain 2000, 2004 and 2011 and Portugal 2019). Although some of the country/elections in the region are among the most polarised in Europe, which has been pointed out by other studies (Gidron, Adams & Horne Citation2020, pp. 36–37), Southern Europe as a whole does not appear to have particularly high levels of polarisation.

As indicated above, the CSES dataset has enabled us to also calculate affective polarisation regarding political parties (and not only leaders) for the available Southern European country/elections (see Table A2 in the online Appendix). Congruent with Reiljan et al. (Citation2021), the polarisation vis-à-vis parties tend to register slightly higher levels than the polarisation vis-à-vis leaders. The difference between both measures is especially high for Spain 2004, where the polarisation regarding parties is more than 0.5 points higher than the polarisation regarding leaders. The main exception is Italy 2006, where the polarisation levels are more notable for feelings about leaders than for parties, may be due to Silvio Berlusconi’s highly divisive leadership.

The ranking of the countries presented here significantly differs from the one presented by Gidron, Adams and Horne (Citation2020) based on the CSES dataset, according to which South European countries (Spain, Greece and Portugal) are among the most affectively polarised countries and the US occupies more intermediate positions. The differences may be due to the fact that, first, we use a spread-of-scores measure of polarisation that also includes individuals not identified with any party.Footnote6 Additionally, we primarily use feelings towards leaders to measure affective polarisation, which tend to be less polarised than feelings towards parties particularly in parliamentary and fragmented party systems (Reiljan et al. Citation2021).

Finally, although the cases are too few to support definite conclusions about general time trends in affective polarisation, we tentatively conclude that there is not a clear pattern in its evolution, which reflects factors unique to particular elections more than the increasing general tendencies (Boxell, Gentzkow & Shapiro Citation2020). Nor do we observe a globally higher level of partisan affective polarisation in Southern Europe compared to other regions of the world. At most, we observe an increase in affective polarisation in Greece, Portugal and Spain in the aftermath of the Great Recession if we take into consideration the data available for the 2015 elections, even though polarisation experiences a significant decline in the subsequent elections in Greece (second election of 2015) and Portugal (2019).

Trends in affective polarisation in Spain

Before analysing our Spanish panel survey data, we ponder how affective polarisation has evolved in Spain over recent decades.Footnote7 Unfortunately, there is a lack of data with the all necessary indicators that allow us to build a complete series of the aggregate measures of affective polarisation for the Spanish party system. In our case, we have computed these aggregate indices based on sentiments towards leaders using data from the CNEP and CSES datasets, with the addition of the E-DEM dataset. The indices are calculated using the formula proposed by Reiljan (Citation2020), with the main difference that we define respondents’ in-groups based on their most-liked leader (for the details, see section D of the online Appendix).

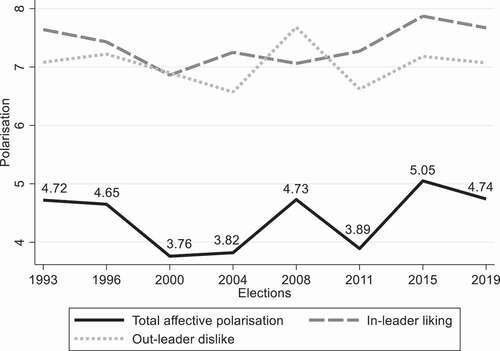

displays the evolution of affective polarisation in Spain between 1993 and 2019. Observing the data on affective polarisation during this time, we can appreciate four important aspects. Firstly, affective polarisation has oscillated quite substantially during these years, showing that this phenomenon is election specific and responds to the dynamics of party competition. Second, the periods of lowest polarisation have happened when the conservative PP obtained the absolute majority (2000 and 2011) with the exception of 2004, when the socialist PSOE won the election. Third, the period with the highest levels of affective polarisation was initiated with the 2008 election when leader of the PSOE, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, won his second consecutive election against Mariano Rajoy, leader of the PP. This period of high affective polarisation was only interrupted in 2011 when the PP gained a large majority during the economic and financial crisis initiated in 2008. After this election, affective polarisation reached its highest peak in the 2015 election, which was marked by the impact of the austerity policies and the emergence of the radical left-wing Podemos. Fourth, the current high levels of affective polarisation were already in place before the arrival of the radical right-wing party, Vox, to the national arena at the end of 2018 with the Andalusian elections. In fact, affective polarisation decreased somewhat in the national election celebrated in April of the following year.

Figure 2. Out-leaders dislike, in-leader liking and total aggregate affective polarisation (in-leader and out-leaders liking difference) in Spain, 1993–2019.Sources: E-DEM, CNEP, CSES.

The study of the evolution of this polarisation index disaggregated by sentiments towards out-party leaders and in-party leader highlights something else about the evolution of affective polarisation in Spain. As it is appreciated in , positive sentiments towards one’s own party leaders have clearly overpassed negative sentiments towards out-party leaders since 2004, constituting in the last decade the main source of affective polarisation. The only exception is 2008, when negative sentiments towards other leaders were at its highest. This constitutes a positive sign for the levels of affective polarisation in Spain, since the most disturbing consequences of this type of polarisation are mainly associated with out-group dislike. Nevertheless, the levels of out-leader dislike continue to be high, oscillating in the last decade between 6.6 (2011) and 7.2 (2015) points.

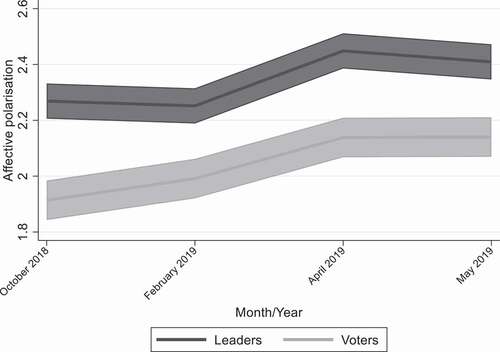

Next to consider is the levels and evolution of affective polarisation during the convulsive months of 2018 to 2019 in Spain when the radical right-wing party, VOX, irrupted in the national arena. draws on the E-DEM panel survey data to show the evolution of the spread-of-scores polarisation indices referring to leaders (WAPSL) and voters (WAPSV) from 2018 to 2019. This figure shows three important aspects. First, in October 2018, affective polarisation was already high, paving the way for the electoral success that the radical right-wing party, Vox, gained in the Andalusian elections (December 2nd) in which this party emerged as the fifth political force with almost 11 per cent of the vote. Second, in the months that followed this initial wave, polarisation grew significantly, paving the way for the electoral success of this same party at the national arena (April 28th). It could be that the electoral success and the arrival of extreme right-wing parties to the institutions might increase affective polarisation (as Bischof & Wagner Citation2019 demonstrate for ideological polarisation), but the Spanish case might also indicate that the arrival and greater visibility of these types of parties are fostered by the growing levels of affective polarisation produced in the system by the other parties. This means that radical right-wing parties do not prosper in context of low polarisation, and required one of high polarisation to grow, giving them greater visibility. Finally, affective polarisation produced by feelings towards leaders is always much higher than feelings towards voters, congruent with previous findings (Druckman & Levendusky Citation2019; Kingzette Citation2021). However, the increase in polarisation of feelings about voters seems to be stronger and more consistent over time.

Figure 3. Affective polarisation regarding leaders (WAPSL) and voters (WAPSV) in Spain, October 2018–May 2019.Source: E-DEM panel dataset.Notes: 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Territorial conflicts have been another source of political confrontation and articulation of the Spanish party system, forming several sub-areas of party competition in many regions (Pallarés & Keating Citation2003). This is especially remarkable during the last years in Catalonia, where confrontation has increased between the state and the regional government about decentralisation and the referendum for independence from the Spanish state (Balcells, Fernández-Albertos & Kuo Citation2021). To what extent are feelings about territorial identities polarised?

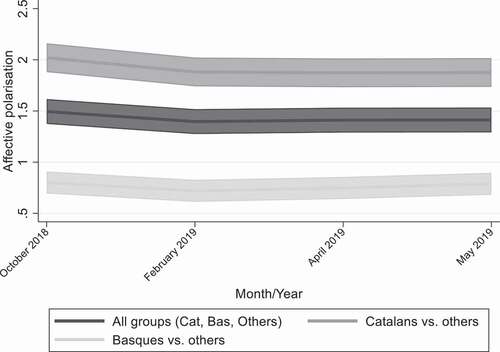

shows that respondents tend to like their own territorial group more than other ones, with a mean difference of around 1.5 points. If we analyse the mean distance per pairs of groups, the conflict produced by the Catalan identity generates the highest levels of territorial affective polarisation, adding an important additional component of polarisation to the Spanish national arena. Concretely, the mean distance from a respondent’s own territorial group is around 2 points. The levels of affective polarisation for the Basque identity are significantly lower, the mean distance here of around 0.8 points. The results for the Basque case are especially remarkable, given that the region used to experience a highly polarised conflict for many years.

Figure 4. Territorial affective polarisation in Spain, October 2018–May 2019.Source: E-DEM panel dataset.Notes: 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Notable in is the stability of this polarisation during the period under study, which clearly contrasts with the upward trend observed for the partisan indices of polarisation. At most, we can observe that the index comparing the sentiments towards Catalans and other groups (as well as the general index including all territorial groups) follows a gentle downward trend. At least for this period and at the aggregate level, the increase in partisan affective polarisation observed in the Spanish case at the national arena does not seem to be attributable to territorial affective polarisation. However, this will be analysed in more detail in the following sections.Footnote8

But to what extent are these trends in affective polarisation related to the evolution of perceived ideological polarisation and ideological extremism? The E-DEM dataset includes the needed measures for only three initial waves, the third of which was completed just before the 28th of April 2019 for the National Elections.Footnote9 The aggregate measures of these indices over the first three waves reveal two important findings (see Figure A1 in section G of the online Appendix). First, there was a tendency in the period to increase both measures of ideological polarisation, but it was reduced and limited. Second, ideological extremism is always lower than the weighted perceived ideological polarisation (Enders & Armaly Citation2019), reflecting that this perception could be inflated by party competition and the political discourses adopted by political elites (Lu & Lee Citation2019; Suhay, Bello-Pardo & Maurer Citation2018). Nevertheless, the increase in aggregate ideological extremism over time is a bit more pronounced than that of perceived ideological polarisation.

We reproduced the data on perceived ideological polarisation and ideological extremism coming from a different sourceFootnote10 and extending the analysed time period to November 2019. It is important not only to display this evolution for a longer period of time, but also because another national election took place on November 10th after several attempts in the parliament to produce even a simple majority to form a coalition government.

contains the aggregate levels of both measures between October 2018 and November 2019.Footnote11 These data confirm a slight increase. As expected given te repetition of national elections in a short time period, the perceived level of ideological polarisation among parties reached its peak in November 2019, just before the general elections, while the highest levels of ideological extremism occurred in the period between the two Spanish general elections.

Figure 5. Ideological polarisation in Spain, October 2018–November 2019.Source: Own calculations from CIS data base, studies no. 3226, 3238, 3247, 3257 and 3267.Notes: 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Individual variation in polarisation in Spain

Utilising the panel design of the E-DEM dataset, we can also estimate the within individuals variation of polarisation in Spain during this time span. contains the average change within individuals across waves of the main polarisation indices.

Table 1. Average within individual change in polarisation in Spain, December 2018–May 2019.

The data displayed in this table aligns with observations at the aggregate level. First, the levels of party-based affective polarisation have increased within individuals, although the increase is greater for voters than for leaders. The greatest individual increase for both partisan affective polarisation indices is between the second and the third waves, just before the Spanish general elections held in April. By contrast, between the third and the fourth waves (before the European Parliament election), the polarisation produced by feelings towards voters does not present a relevant increase, while the polarisation produced by feelings towards leaders experiences a significant decline. These results show how the context of party competition influences this type of polarisation (Hernández, Anduiza & Rico Citation2021).

Second, ideological polarisation has also increased within individuals, and the increase of ideological extremism during this period has been greater than that observed with perceived ideological polarisation, both on average and between the second and third waves. Finally, the territorial affective polarisation regarding Catalans decreased within individuals, especially between the first and second waves.Footnote12

The multidimensional nature of affective polarisation and its relationship with ideological polarisation

Are the different conflicts and social identities fully aligned with the left-right division and the existing partisan identities? To answer this question, we have conducted a dimensional analysis using the E-DEM dataset. The first selected variables for this analysis are the partisan affective polarisation measures for parties, leaders and voters, as well as the ideological polarisation indices. Second, we have also included the territorial affective polarisation indices based on sentiments towards different territorial identities. Finally, we have utilised data from feeling thermometers for immigrants, refugees and also people from other religions. Although we were not able to build polarisation indices for these last three groups based on in-group/out-group feelings, the sentiment scales towards these groups can be included in the multidimensional analysis.

The results of the dimensional analysis with all of these indicators are displayed in , which contains the varimax rotated factor loadings (only those with the scores above 0.3) of these items for the second and third waves (the only ones containing all these items). The results show the presence of three very distinctive factors. The first includes all the party-based polarisation indices, including both the affective polarisation measures (parties, voters and leaders) and the ideological ones, although the latter have significantly lower loadings. The second contains the cultural/nativism items, which include feelings towards immigrants, refugees, and, with quite lower factor loadings, people from other religions. The third is formed by the territorial affective polarisation indices, with very similar loadings for the two pairs of territorial groups. Thus, it seems that affective polarisation could be a multidimensional phenomenon that does not always fully merge with the polarisation produced around partisan and ideological identities.Footnote13

Table 2. Factor loadings for the affective polarisation indices in Spain, February and March 2019 (Varimax rotated)*.

On the other hand, we are interested in exploring to what extent partisan affective polarisation is related to ideological polarisation and territorial affective polarisation in Spain. As explained above, the literature shows that there is a significant, albeit imperfect, relationship between ideological and affective polarisation. Moreover, and despite the fact that territorial and partisan affective polarisation constitute distinct dimensions, it could be expected that the former would estimulate the latter due to the increasing alignment of territorial and partisan identities in a context characterised by a strong political confrontation around the territorial divide (e.g. Mason Citation2018a). To obtain a greater understanding of these relationships, we refer to our panel survey and estimate regression models with individual fixed effects using wave dummies (double-way fixed effects) and standard errors clustered on individuals. The dependent variable is affective polarisation regarding party leaders. As independent variables we have included weighted perception of ideological polarisation, ideological extremism and territorial affective polarisation regarding Catalan identity. As controllers, other important potential sources of partisan affective polarisation include the left–right scale (polarisation could be higher at a result of moving towards one side of the ideological spectrum), evaluation of the economic situation, evaluation of the situation with regard to corruption, personal economic uncertainty index, and subjective well-being (see section E of the online Appendix for the details about these variables).

As shown in Model 1 of , increases in perceived ideological polarisation, ideological extremism and territorial affective polarisation lead to higher levels of partisan affective polarisation within individuals. Although we cannot demonstrate this empirically in this model, the direction of these relationships is likely reciprocal. Even though the effect of territorial affective polarisation is weaker and a bit less significant compared to that exerted by ideological factors, the results suggest that the Catalan crisis may have also contributed to fuel the polarisation of feelings about leaders. This finding contrasts with the temporal evolution of the territorial polarisation described above, which does not match the upward trend of partisan affective polarisation. Finally, none of the control variables seem to influence the evolution of affective polarisation in each individual.

Table 3. Predictors of affective polarisation regarding leaders (double-way fixed effects regressions).

Another source of affective polarisation regarding leaders could be the increase in extremism on different salient policy-issues. Miller (Citation2020) explores the levels of polarisation on different issues in Spain and their trends over the last decades, showing that the polarisation surrounding concrete policies is lower than ideological positions. Similarly, we have calculated extremism indexes for four different issues: government decentralisation, immigration, socio-economic issues (including redistribution, public services and state interventionism), and socio-cultural issues (including abortion, women working and same sex marriage). These indices have also been calculated by groups of respondents defined by their party identification (for the aggregate levels and trends of these extremism indices, see Figures A2–A5 in section G of the online Appendix). Notably, respondents who identified with the radical right-wing party Vox tend to present the highest levels of extremism on all five issues (together with those identified with the Catalan and Basque nationalist parties in the decentralisation issue), and the extremism levels on socio-cultural, economic and, especially, immigration issues among Vox supporters have increased during the period analysed here, which is congruent with the ideological profile of the party.

In Model 2 of , these four issue extremism indices are included as independent variables only, together with the scales of opinion on these issues and the control variable included in the previous model (see section E of the online Appendix for the details about these variables). The results show that among them, only increases in extremism on the immigration issue are related to partisan affective polarisation within individuals at a conventional level of significance, although the effect is not very strong. This is congruent with the polarising effects of the immigration issue found in the previous literature (e.g. Harteveld Citation2021a). Moreover, extremism on socio-economic issues is also associated with this type of polarisation, although only at a confidence level of 90 per cent. Opinion on immigration and socio-cultural issues are also related to partisan affective polarisation at a confidence level of 90 per cent, in the sense that respondents who move towards more restrictive views on immigration and towards more leftist positions on economy increase the polarisation of feelings about leaders.

Finally, we have estimated another final model with all the variables selected in the preceding ones we just estimated. Results displayed in the same table (Model 3) confirm the findings described previously. Although we cannot imply any causality in these findings, the results suggest that partisan affective polarisation does not really depend on factors such as economic evaluations or personal socio-economic conditions, nor on the extremism around concrete policy-issues, with the exception of immigration, although in the last model it loses some strength and significance. By contrast, at least for the period analysed here, partisan affective polarisation in Spain seems to be mainly the result of perceived ideological polarisation among elites, extreme ideological identities and, to a lower degree, the polarisation surrounding the Catalan identity.Footnote14

About the content of this volume

The rest of the articles in this special issue cover different topics on affective polarisation in Spain in an attempt to contribute to some of the theoretical debates discussed in this introductory article. More concretely, there are two groups of articles based on the topic covered. The first group comprises four articles that address the potential elements that might foster affective polarisation. The second group comprises three articles that cover some of the behavioural and attitudinal consequences of affective polarisation.

Regarding the first group of articles, Rodríguez, Santamaría and Miller (Citation2022) estimate the causal effect of elections on partisan affective polarisation combining two different methodological strategies designed to take advantage of the panel structure. They pay special attention to understanding the channels through which the effect of elections on partisan affective polarisation is manifested. To do so, they estimate the conditional effects on three ideological groupings (left, centre and right) and whether the increase in polarisation is related to changes in attitudes towards co-partisans (in-group) or non-co-partisans (out-group).

The second article is co-authored by Garmendia Madariaga and Riera (Citation2022), who use information from two CIS panel studies and the E-DEM dataset to determine how polarised Spanish voters were around the conflict articulated by territorial identities when the radical parties Podemos and Vox entered the national parliament for the first time. This article shows how the entrance of radical parties into the political competition might affect other political dimensions of polarisation that go beyond what is normally linked to traditional left–right competition.

The third article, by Padró-Solanet and Balcells (Citation2022), addresses in a very innovative way the effect of the media diet on affective polarisation in Spain. Their analysis takes advantage of web-tracking data to directly observe the individual’s habits of media consumption instead of simply relying on self-reported data. Such an approach has the advantage of providing a richer and more detailed picture of the individual’s media diet. While some indicators of media diet diversity point towards a reduction of ideological extremism, some others show seems to be linked with an increase of the polarisation produced by territorial identities. Overall, this article illustrates the complex relationship between media diet and affective polarisation.

The fourth article, by Lorenzo-Rodríguezo and Torcal (Citation2022), deals with the effects of social media on affective polarisation (partisan and territorial). More concretely, they use a survey experiment to estimate the effect of being exposed to anti-out-group parties and anti-Catalans/Spanish expressions in the tweets sent by primary political candidates during the 2019 EU Spanish electoral campaign. Despite the non-randomisation of the treatment, which would give the experiment greater external validity, these authors are convincing in demonstrating the very limited effect of candidates’ messaging on these two dimensions of affective polarisation.

Concerning the second group, Serani (Citation2022) conducts an analysis on the association between partisan affective polarisation and propensity to vote in Spain. Utilising two waves of E-DEM (third and fourth ones), this author evaluates the impact of previous polarisation on individual propensity to vote. This is a relevant and almost unique contribution to the study of the effect of affective polarisation on electoral participation.

The second article of this group, by Rodon (Citation2022), addresses the hitherto neglected relationship between affective polarisation and vote choice in Spain, a context in which distrust between different and opposite groups occurs both on ideological and territorial terms. This is also an innovative contribution which shows how affective polarisation can, at the same time and in a different way, affect political behaviour and political competition, especially in contexts where party competition is multidimensional, as it is in Spain.

Finally, Torcal and Carty (Citation2022) use the panel structure of the data to explore how much and in what direction affective political polarisation can affect political trust. This topic has been neglected in the comparative literature on affective polarisation. This contribution sheds light on how individual increase in political trust might be sometimes an undesirable consequence of increasing affective polarisation, especially when we distinguish the effect of out-group polarisation from the one produced by the increased in polarisation due to the liking of the partisan in-group.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (770.1 KB)Supplementary material

Supplementary data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2022.2044236.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mariano Torcal

Mariano Torcal is a Full Professor in Political Science and ICREA Research Fellow at the Department of Political and Social Science at the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, and Director of the Research and Expertise Centre for Survey Methodology (RECSM). He has published articles on topics such as political disaffection, political trust and satisfaction with democracy, electoral behaviour, political participation and party system institutionalisation in major international journals.

Josep M. Comellas

Josep M. Comellas holds a PhD in Political and Social Sciences from the Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Barcelona, and is a researcher at the Research and Expertise Centre for Survey Methodology (RECSM). He spent a research visit at the University of Amsterdam (UvA). His work focuses on the causes and consequences of affective polarisation in comparative perspective, and on the determinants of the support for the radical right.

Notes

1. For more on the CNEP and its surveys, see: u.osu.edu/cnep.

2. This survey was administered by Netquest using their large online non-probabilistic panel: https://www.netquest.com/es/home/encuestas-online-investigacion.

3. We have used both feelings and trust scales to take advantage of all the richness of our dataset. In addition, we have also calculated the territorial affective polarisation indices using only the feelings scales towards the territorial groups. Pearson’s correlation coefficients between both types of affective polarisation indices (those constructed with feelings and trust vs. those built only with feelings) are very high, ranging between 0.92 and 0.94.

4. As explained earlier, affective polarisation at the aggregate level can also be computed by the formula proposed by Reiljan (Citation2020). However, the country ranking according to this formula (using like-dislike feelings towards leaders) is quite similar (see column 2 in Table A1). In fact, the correlation between these two measures is a high 0.90 (see section D of the Appendix for more details about this aggregate affective polarisation index).

5. In a country of 27 million inhabitants, the estimate is that the civil war resulted in the killing/starvation of more than one million Mozambicans and the displacement of five million more. It is no wonder that the residue of that conflict lasted until 2004.

6. To the extent that Spain, Portugal and Greece have a low percentage of people identified with a particular party, and that those who are identified with a party tend to hold higher levels of affective polarisation (e.g. Iyengar, Sood & Lelkes Citation2012), the inclusion of individuals without party identification in the measure may weaken the levels of affective polarisation in Southern Europe. A preliminary analysis using our main dataset (CNEP) reveals that the average percentage of respondents who feel close to a particular party across the different selected elections is 51.3 per cent for Spain, 43.0 per cent for Portugal, 60.4 per cent for Greece and 62.1 per cent for the U.S.

7. See also Orriols and León (Citation2020) for the evolution of affective polarisation in Spain during the last two decades. However, they use the probabilities to vote and the evaluations of leaders’ performance as indicators of affective polarisation.

8. If we observe the levels and trends of the territorial affective polarisation indices constructed only with feelings towards territorial groups (and, hence, not including trust scales), the conclusions are very similar. The main difference is that the mean levels of polarisation are even somewhat higher (see Figure A6 in the Appendix).

9. Both measures are calculated based on 11-point left-right scales.

10. CIS database, study nos. 3226, 3238, 3247, 3257 and 3267.

11. In the CIS database, the original left-right scales range from 1 to 10. However, we rescaled them to vary from 0 to 10.

12. The decrease in affective polarisation regarding Catalans, especially between the first and second waves, is even stronger when this index is calculated only using feelings scales (see Table A3 in the Appendix).

13. The same results are obtained if the territorial affective polarisation indices introduced in the dimensional analysis are calculated only using feelings scales towards territorial groups (see Table A4 in the Appendix).

14. If affective polarisation regarding Catalans measured only with feelings scales is introduced into the models (instead of the index calculated with both feelings and trust scales), the results remain quite the same. At most, the effect of territorial affective polarisation loses some strength, although this variable remains significantly related to partisan affective polarisation (see Table A5 in the Appendix).

References

- Alvarez, M. R. & Nagler, J. (2004) ‘Party system compactness: measurement and consequences’, Political Analysis, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 46–62.

- Balcells, L., Fernández-Albertos, J. & Kuo, A. (2021) ‘Secession and social polarization. Evidence from Catalonia’, UNU-WIDER Working Paper 2021/2.

- Bankert, A., Huddy, L. & Rosema, M. (2017) ‘Measuring partisanship as a social identity in multi-party systems’, Political Behavior, vol. 39, pp. 103–132.

- Bartolini, S. & Mair, P. (1990) Identity, Competition and Electoral Availability: The Stabilisation of European Electorates 1885–1985, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Bischof, D. & Wagner, M. (2019) ‘Do voters polarize when radical parties enter parliament?’, American Journal of Political Science, vol. 63, pp. 888–904.

- Bougher, L. D. (2017) ‘The correlates of discord: identity, issue alignment, and political hostility in polarized America’, Political Behavior, vol. 39, pp. 731–762.

- Boxell, L., Gentzkow, M. & Shapiro, J. M. (2020) ‘Cross-country trends in affective polarization’, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, No. 26669.

- Criado, H., Herreros, F., Miller, L. & Ubeda, P. (2015) ‘Ethnicity and trust: a multifactorial experiment’, Political Studies, vol. 63, no. S1, pp. 131–152.

- Criado, H., Herreros, F., Miller, L. & Ubeda, P. (2018) ‘The unintended consequences of political mobilization on trust: the case of the secessionist process in Catalonia’, Journal of Conflict Resolution, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 231–253.

- Curini, L. & Hino, A. (2012) ‘Missing links in party-system polarization: how institutions and voters matter’, The Journal of Politics, vol. 74, no. 2, pp. 460–473.

- Druckman, J. N. & Levendusky, M. S. (2019) ‘What do we measure when we measure affective polarization?’, Public Opinion Quarterly, vol. 83, no. 1, pp. 114–122.

- Enders, A. M. & Armaly, M. T. (2019) ‘The differential effects of actual and perceived polarization’, Political Behavior, vol. 41, pp. 815–839.

- Ezrow, L. (2007) ‘The variance matters: how party systems represent the preferences of voters’, Journal of Politics, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 182–192.

- Franklin, M. N., Mackie, T. T. & Valen, H. (1992) Electoral Change: Responses to Evolving Social and Attitudinal Structures in Western Countries, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Garmendia Madariaga, A. & Riera, P. (2022) ‘Territorial polarisation after radical parties’ breakthrough in Spain’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 27, no. 1.

- Gidron, N., Adams, J. & Horne, W. (2020) American Affective Polarization in Comparative Perspective, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Harteveld, E. (2021a) ‘Fragmented foes: affective polarization in the multiparty context of the Netherlands’, Electoral Studies, vol. 71, pp. 102332.

- Harteveld, E. (2021b) ‘Ticking all the boxes? A comparative study of social sorting and affective polarization’, Electoral Studies, vol. 72, pp. article 102337.

- Hazan, R. Y. (1995) ‘Center parties and systemic polarization: an exploration of recent trends in Western Europe’, Journal of Theoretical Politics, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 421–445.

- Hernández, E., Anduiza, E. & Rico, G. (2021) ‘Affective polarization and the salience of elections’, Electoral Studies, vol. 69, pp. article 102203.

- Hetherington, M. J. (2009) ‘Putting polarization in perspective’, British Journal of Political Science, vol. 39, pp. 413–448

- Hetherington, M. J., Long, M. T. & Rudolph, T. J. (2016) ‘Revisiting the myth: new evidence of a polarized electorate’, Public Opinion Quarterly, vol. 80, no. S1, pp. 321–350.

- Hobolt, S. B., Leeper, T. J. & Tilley, J. (2020) ‘Divided by the vote: affective polarization in the wake of the Brexit referendum’, British Journal of Political Science. online.

- Hooghe, L. & Marks, G. (2018) ‘Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage’, Journal of European Public Policy, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 109–135.

- Huddy, L. (2001) ‘From social to political identity: a critical examination of social identity theory’, Political Psychology, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 127–156.

- Huddy, L., Bankert, A. & Davies, C. (2018) ‘Expressive versus instrumental partisanship in multiparty European systems’, Advances in Political Psychology, vol. 39, no. S1, pp. 173–199.

- Huddy, L., Mason, L. & Aarøe, L. (2015) ‘Expressive partisanship: campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity’, American Political Science Review, vol. 109, no. 1, pp. 1–17.

- Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N. & Westwood, S. J. (2019) ‘The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States’, Annual Review of Political Science, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 129–146.

- Iyengar, S., Sood, G. & Lelkes, Y. (2012) ‘Affect, not ideology: a social identity perspective on polarization’, Public Opinion Quarterly, vol. 76, no. 3, pp. 405–431.

- Iyengar, S. & Westwood, S. J. (2015) ‘Fear and loathing across party lines: new evidence on group polarization’, American Journal of Political Science, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 690–707.

- Kingzette, J. (2021) ‘Who do you loathe? Feelings towards politicians vs. ordinary people in the opposing party’, Journal of Experimental Political Science, vol. 8, pp. 75–84.

- Kitschelt, H. & Rehm, P. (2015) ‘Party alignments: change and continuity’, in The Politics of Advanced Capitalism, eds P. Beramendi, S. Häusermann, H. Kitschelt & H. Kriesi, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 179–201.

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Dolezal, M., Helbling, M., Höglinger, D., Hutter, S. & Wüest, B. (2012) Political Conflict in Western Europe, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Lauka, A., McCoy, J. & Firat, R. B. (2018) ‘Mass partisan polarization: measuring a relational concept’, American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 107–126.

- Lelkes, Y. (2018) ‘Affective polarization and ideological sorting: a reciprocal, albeit weak, relationship’, The Forum, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 67–79.

- Levitsky, S. & Ziblatt, D. (2018) How Democracies Die, Crown Publishing Group, New York.

- Lipset, S. M. & Rokkan, S. (1967) Party Systems and Voter Alignments, Free Press, New York.

- Lorenzo-Rodríguez, J. & Torcal, M. (2022) ‘Twitter and affective polarisation: following political leaders in Spain’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 147–173.

- Lu, Y. & Lee, J. K. (2019) ‘Partisan information sources and affective polarization: panel analysis of the mediating role of anger and fear’, Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, vol. 96, no. 3, pp. 767–783.

- Lupu, N. (2015) ‘Party polarization and mass partisanship: a comparative perspective’, Political Behavior, vol. 37, pp. 331–356.

- MacKuen, M., Wolak, J., Keele, L. & Marcus, G. E. (2010) ‘Civic engagements: resolute partisanship or reflective deliberation’, American Journal of Political Science, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 440–458.

- Mason, L. (2018a) Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Out Identity, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Mason, L. (2018b) ‘Ideologues without issues: the polarizing consequences of ideological identities’, Public Opinion Quarterly, vol. 82, no. S1, pp. 866–887.

- McCarty, N., Poole, K. T. & Rosenthal, H. (2006) Polarized America: The Dance of Ideology and Unequal Riches, MIT Press, Cambridge.

- McCoy, J. (2019) ‘“Pernicious polarizations” threat to democracy: lessons for the U.S. from abroad’, APSA Newsletter Comparative Politics, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 22–29.

- McCoy, J., Rahman, T. & Somer, M. (2018) ‘Polarization and the global crisis of democracy: common patterns, dynamics, and pernicious consequences for democratic polities’, American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 16–42.

- McCoy, J. & Somer, M. (2019) ‘Toward a theory of pernicious polarization and how it harms democracies: comparative evidence and possible remedies’, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 681, no. 1, pp. 234–l271.

- Miller, L. (2020) ‘Polarización en España: más divididos por ideología e identidad que por políticas públicas’, EsadeEcPol Insight, vol. 18, pp. 1–14.

- Orriols, L. & León, S. (2020) ‘Looking for affective polarisation in Spain: PSOE and Podemos from conflict to coalition’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 25, no. 3–4, pp. 351–379.

- Padró-Solanet, A. & Balcells, J. (2022) ‘Media diet and polarisation: evidence from Spain’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 27, no. 1.

- Pallarés, F. & Keating, M. (2003) ‘Multi-level electoral competition: regional elections and party systems in Spain’, European Urban and Regional Studies, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 239–255.

- Reiljan, A. (2020) ‘“Fear and loathing across party lines” (also) in Europe: affective polarisation in European party systems’, European Journal of Political Research, vol. 59, pp. 376–396.

- Reiljan, A., Garzia, D., da Silva, F. F. & Trechsel, A. H. (2021) ‘Patterns of affective polarization in the democratic world: comparing the polarized feelings towards parties and leaders’, paper presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions, Online conference, 17–28 May.

- Rodon, T. (2022) ‘Affective and territorial polarisation: the impact on vote choice in Spain’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 27, no. 1.

- Rodríguez, I., Santamaría, D. & Miller, L. (2022) ‘Competition and partisan affective polarisation in Spain’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 27, no. 1.

- Rogowski, J. C. & Sutherland, J. L. (2016) ‘How ideology fuels affective polarization’, Political Behavior, vol. 38, pp. 485–508.

- Rudolph, T. J. & Hetherington, M. J. (2021) ‘Affective polarization in political and nonpolitical settings’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 591–606.

- Serani, D. (2022) ‘In-party like, out-party dislike and propensity to vote in Spain’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 27, no. 1.

- Sides, J., Tesler, M. & Vavreck, L. (2018) Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and Battle for the Meaning of America, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Somer, M. (2019) ‘Turkey: the slippery slope from reformist to revolutionary polarization and democratic breakdown’, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 681, no. 1, pp. 42–61.

- Somer, M. & McCoy, J. (2018a) ‘Transformations through polarizations and global threats to democracy’, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 681, no. 1, pp. 8–22.

- Somer, M. & McCoy, J. (2018b) ‘Déjà vu? Polarization and endangered democracies in the 21st century’, American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 3–15.

- Suhay, E., Bello-Pardo, E. & Maurer, B. (2018) ‘The polarizing effects of online partisan criticism: evidence from two experiments’, The International Journal of Press/Politics, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 95–115.

- Svolik, M. W. (2019) ‘Polarization versus democracy’, Journal of Democracy, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 20–32.

- Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. C. (1979) ‘An integrative theory of intergroup conflict’, in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds W. G. Austin & S. Worchel, Brooks/Cole, Monterrey, pp. 33–47.

- Thomassen, J. & Rosema, M. (2009) ‘Party identification revisited’, in Political Parties and Partisanship: Social Identity and Individual Attitudes, eds J. Bartle & P. Bellucci, Routledge/ECPR Studies in European Political Science (No. 57), Oxford, pp. 42–59.

- Torcal, M. & Carty, E. (2022) ‘Partisan sentiments and political trust: a longitudinal study of Spain’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 27, no. 1.

- Torcal, M., Santana, A., Carty, E. & Comellas, J. M. (2020) ‘Political and affective polarisation in a democracy in crisis: the E-DEM panel survey dataset (Spain, 2018–2019)’, Data in Brief, vol. 32, pp. 106059.

- Wagner, M. (2020) ‘Affective polarization in multiparty systems’, Electoral Studies, vol. 69, pp. article 102199.

- Ward, D. G. & Tavits, M. (2019) ‘How partisan affect shapes citizens’ perception of the political world’, Electoral Studies, vol. 60, pp. article 102045.

- Webster, S. W. & Abramowitz, A. I. (2017) ‘The ideological foundations of affective polarization in the U.S. electorate’, American Politics Research, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 621–647.

- Westwood, S. J., Iyengar, S., Walgrave, S., Leonisio, R., Miller, L. & Strijbis, O. (2018) ‘The tie that divides: cross-national evidences of the primacy of partyism’, European Journal of Political Research, vol. 57, pp. 333–354.