ABSTRACT

The 2022 Italian general election marked a new step in the unprecedented instability experienced by the Italian party system over the past 15 years. This article presents and discusses the outcome of the election within the deinstitutionalised Italian party system. The most remarkable results were the unprecedented success of the radical-right FDI (Fratelli d’Italia – Brothers of Italy) led by Giorgia Meloni (who would become the first female prime minister in Italy) and a historic drop in voter turnout. In particular, by employing original individual-level survey data, we investigate the impact of territory on the vote, the individual-level dynamics behind the results, and the overall picture emerging in terms of the Italian party system.

Coming somewhat by surprise due to the resignation of the Draghi government in July before the end of the legislative term, the Italian general election was held on 25 September 2022. Its outcome represents a rightward turn in the country’s politics. Not just because the centre-right coalition won a large parliamentary majority, an outcome that has not happened since 2008, but rather, because FDI (Fratelli d’Italia – Brothers of Italy), which is far on the right of the political spectrum, emerged as the largest party by far both within the winning coalition and overall.

The success of the centre-right, and particularly of FDI, whose identity oscillates between that of the post-fascist legacy and that of the populist radical right (Puleo & Piccolino Citation2022) but which could also become that of genuine conservatism, is not the story of an unexpected victory. All the indications – from the results of the 2019 European Parliament (EP) election to the surveys of the major polling companies, which gave the centre-right a large margin of advantage much before and throughout the campaign – suggested that the centre-right coalition would beat the other line-ups, i.e. the centre-left coalition, the M5S (Movimento 5 Stelle – Five Star Movement) and the new centrist subject AZ-IV (Azione-Italia Viva – Action-Italy Alive). And in fact, the centre-right was victorious. However, the victory that gave the centre-right the largest parliamentary majority of any winning coalition since 1994 was more the product of a split among the alternative political forces than the size of its electoral support.

For the first time in Italy’s republican history, the government formed after the election is truly right-wing (far more than centre-right) and led by a female leader, Giorgia Meloni, who has been close to political leaders such as Viktor Orbán and Santiago Abascal, although recently she has tried to portray herself and her party as less radical and more moderate, possibly for tactical reasons. It is therefore very likely that European countries and EU institutions alike will keep a close watch on Italian political developments for at least the next few months.

The outcome of the 2022 Italian election, however, is much more than the victory of the right-wing coalition and the subsequent birth of the Meloni government. It also tells us the story of an ongoing change that does not seem to be landing on a stable equilibrium. This change concerns the electoral competition on both the supply side and the demand side. On the one hand, parties are still proving to be organisationally fragile and thus unable to establish or maintain social roots, as well as to build lasting political alliances. On the other, voters appear increasingly disillusioned with the parties themselves and their performance in government and thus tend to change their previous vote choices, either by rewarding protest and opposition parties or by abstaining. All this reverberates on the party system as a whole, which is now deinstitutionalised, that is, characterised by chronic instability and unpredictability that threaten to undermine its legitimacy.

So, in order to understand how the results just described came about and what consequences they entail, it is necessary to present the events of the 2018–2022 legislature, the list- and coalition-building process, and the electoral campaign (first section). We then provide an account of the electoral turnout and of its historic drop, as well as a description of the results of the Chamber and Senate elections (second section), referring to the votes and seats obtained both by the coalitions and by the party lists, and to their territorial distribution (third section). After that, we analyse the electoral behaviour employing original individual-level survey data, pointing out both the main parties’ social bases and the individual shifts in voting (fourth section). We then move on by analysing the transformation which the Italian party system overall has undergone for more than a decade (fifth section). The final section consists of a discussion of the prospects following the election.

Background

Cabinet alternation and political turmoil after the great recession

The 2022 Italian general election marked the third highly volatile election in a row, indicating the incredible turbulence experienced by the Italian party system over the past 15 years (Emanuele & Chiaramonte Citation2020). As visible in , after the collapse of the centre-right coalition revolving around Silvio Berlusconi’s PDL (Popolo delle Libertà – People of Freedom), this instability also translated into new patterns of governmental coalitions – abandoning the bipolar format that had characterised the 1996–2011 period (Chiaramonte Citation2015). First, grand coalitions including forces from both the centre-right and centre-left were experimented with, under either technocratic (Mario Monti) or political PMs (Enrico Letta, Matteo Renzi, Paolo Gentiloni), after the partially undecisive 2013 general election, which saw the explosive debut of the M5S (demolishing the bipolar format), but which still granted centre-left the control of one branch of Parliament (D’Alimonte Citation2013).

Table 1. Italian cabinets and governmental majorities, 2008–2022.

Then, the 2018 election resulted in a completely hung Parliament (Chiaramonte et al. Citation2018; Paparo Citation2018). For the first time since the beginning of the Second Republic in 1994, no pre-electoral alliances had a majority of seats in either branch of Parliament. After three months of negotiations, the two parties emerging as winners of the election, although on opposite fronts, agreed to form a coalition government. They were both challengers: M5S and Lega (Lega-Salvini Premier – League-Salvini Premier). For the PM position, the leading party put forth Giuseppe Conte. He was a non-political figure – a law professor, who had already been designated before the election as minister for the public bureaucracy of the future M5S cabinet (Conti, Pedrazzani & Russo Citation2020).

The leaders of the two coalition partners (Luigi Di Maio for the M5S and Matteo Salvini for the Lega) would serve as vice-prime ministers, while also holding important ministerial posts. The former would lead both the Labour and the Economic Development departments, while the latter would be Minister of the Interior. From those posts, they pushed for the policies on which they had run the election. Salvini had stricter measures on immigration enacted, through the so-called ‘Security Decrees’. Moreover, he delivered on the reduction of the pension age, thanks to the so-called ‘Quota 100’. Both the reduction of immigration flows and pension age have long been supported by a majority of voters (see Emanuele, Maggini & Paparo Citation2020; ). On the other side, Di Maio had basic citizenship income approved. This was a relevant budget expense which would become a pivotal and divisive issue for the years to come ().

Table 2. Priorities and preferences of Italian voters in 2022 for selected policy issues.

Immediately after the general election, and throughout the whole Conte I cabinet, opinion polls indicated the retreat of the M5S and the parallel rise of its governmental partner (Tronconi & Valbruzzi Citation2020). This was recorded in the 2019 EP election, in which the power balance between M5S and Lega was completely reversed (Landini & Paparo Citation2019). The latter doubled its performance compared to the general election, while the former halved its own.

The leader of the Lega thought he could capitalise on his popularity in an early election and dissolved the government. However, Parliament was not dissolved, as it was able to form a new governmental coalition. The plurality party (M5S) would now find allies in the centre-left front, starting with the PD (Partito Democratico – Democratic Party). It was the founder himself, Beppe Grillo, who first suggested and then actively intervened to make the party digest such a turn. On the other front, the PD secretary (Nicola Zingaretti) was also reluctant to accept forming a government with the M5S, but he was forced by the desire of the party in public office to avoid the early election (the former party secretary, Renzi, in particular).

Once again, the M5S was able to impose on its (new) partners Conte as PM. Thus, in September 2019, the Conte II cabinet received the confidence vote from Parliament. Di Maio would move to the Foreign Affairs ministry. The PD received many important posts, including the Ministry of Economy for Roberto Gualtieri, former chairman of the EP Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs. A technical figure was chosen to replace Salvini at the Interior. The left minor party named LEU (Liberi e Uguali – Free and Equal) was also given a ministry position which would prove particularly important in upcoming years – Roberto Speranza was chosen as the Minister of Health.

A few days after the birth of the new cabinet, the PD figure who most openly had supported the coalition cabinet with the M5S, Renzi, left the party to form Italia Viva. Two ministers would join the new party, which remained part of the governmental majority in Parliament.

In March 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic exploded across Italy. The initial outbreak was in Codogno, Lombardy. In the span of a couple of weeks, the whole country found itself under lockdown, after a series of increasingly stronger social distancing measures had not proved successful in containing the spread of the virus.

The management of the public health crisis, and its balancing with the necessities of the economy, soon became the crucial issue for the government to deal with and for public opinion to debate and take position on. The government chose a strict policy, imposing face masks, social distancing, and isolation measures. This stance opened the government up to critics from the right-wing parties, namely FDI and Lega, who suggested more emphasis on the economy.

However, it would not be on the management of the pandemic that the Conte II cabinet would fall, but rather on the crucial issue of how to manage the funds of the Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza (PNRR, National Recovery and Resilience Plan), still a top priority when the election occurred (). This was a € 191B allocation by the EU to Italy aimed at relieving the economic consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic, while also investing in the longer-term efficiency of the country through specific investments in digitisation and innovation, ecological transition, and social inclusion.

After months of tensions regarding how to organise the PNRR governance and then its implementation, in January 2021 Renzi withdrew IV ministerial delegation, formally opening the governmental crisis. The cabinet tried to collect MPs one by one, especially Senators, to maintain majority support. However, when the crucial confidence vote took place in the Senate, the government received only 156 votes: good enough not to be dismissed, but less than the majority (161).

Despite being not formally without confidence, Conte resigned. The President of the Republic urged political parties to support a national-alliance cabinet, led by former ECB governor Mario Draghi, in consideration of the health and economic emergencies. All major parties but one responded to the call. The exception was FDI, constantly in the opposition since its foundation (in 2012 by Meloni).Footnote1

The Draghi cabinet had an agenda based on structural reforms of many important economic and social sectors, the execution of which were necessary conditions to receiving the PNRR funds from the EU. Just as with the Monti technocratic-led cabinet 10 years before, however, parties started off being extremely deferent to the cabinet and its priorities but renewed their autonomy after a few months, pulling the cabinet in many different directions and slowing down its ability to realise its agenda.

In January 2022, Parliament met in a joint session to elect the new President of the Republic, after Sergio Mattarella ended his seven-year term. This was a further turning point of the legislature. After a year of the Draghi cabinet, the one party benefiting from the government/opposition configuration was the one party not supporting Draghi – FDI. Polls indicated that FDI moved from around 15 to over 20 per cent. The PM was the front-runner to move from Palazzo Chigi to the Quirinale Palace, ascending to Head of State. However, the growing tensions within his large majority made it impossible for him to be elected. In the end, after various attempts to elect different figures with varying majorities, Parliament was forced to ask Mattarella to serve for a second seven-year term.

A new crisis, the war in Ukraine, arose in February 2022, and its economic consequences, especially on energy costs, would soon become the top priority in the minds of the voters (). Conte, now the leader of the M5S, increased the level of conflict with the cabinet throughout 2022 by making requests related both to the economy (in particular, not reforming the basic citizenship income too much) and to the war (to stop sending weapons to Ukraine, a position supported by a majority of Italians, as shown in ). In the end, considering the abandonment of the path to mainstream and the confirmation of the two-term limit for MPs, former party leader Di Maio split and formed new parliamentary groups with 10 senators and 51 deputies, eventually founding a new party – IC (Impegno Civico – Civic Engagement).

Contrary to Di Maio’s desires to reinforce the cabinet, it would in fact be the beginning of the end for Draghi. Conte found himself more and more in a corner and, consequently, raised the level of conflict with the PM in order to be visible and relevant. Between tight international requirements and budget limitations, Draghi was unwilling to compromise. The centre-right parties of the government, Lega and FI (Forza Italia – Go Italy), saw the opportunity to end their participation in the grand-coalition cabinet, which was clearly damaging them to the benefit of FDI, without paying the price for having forced the early election.

Coalition building and electoral campaign

The situation collapsed perhaps beyond the intentions of its starters. Draghi resigned on July 21, and President Mattarella called for a new general election on September 25. The centre-right parties, despite having walked different paths during the legislature, were immediately able to form a unified coalition, including (exactly as in 2018, see De Lucia & Paparo Citation2019) FDI, FI, Lega, and a fourth list composed of various minor centrist parties – named NM (Noi Moderati – Us Moderates).

The opposite front would prove unable to do the same. The PD secretary, former PM Letta, had long worked to form a wide, encompassing pre-electoral coalition, including the M5S. However, the decision by Conte to withdraw his support from the Draghi cabinet proved to be too much for them to run as allies, given the emphasis the PD gave to the execution of the ‘Draghi agenda’, so fiercely opposed by the M5S. Letta had hoped to form at least a somewhat-wide coalition, by joining forces with Azione – the centrist, liberal new party led by former minister of economic development, Carlo Calenda. However, the day after signing the agreement with Calenda, the PD signed an electoral pact with EV-SI (Europa Verde-Sinistra Italiana – Europe Green-Italian Left), who spoke loudly against the Draghi agenda, and Calenda decided to run solo – eventually forming a unified list with Renzi’s IV. Letta thus found himself in a dangerous position. He had hoped his party would be the pivotal actor of the anti-Meloni front. Instead, he was worn down by both the centre (Calenda) and M5S, without being successful in his campaign based on a dual contraposition between him and Meloni, given the large advantage attributed by the polls to the latter.

Meloni was the front-runner, and she campaigned on silencing the extreme positions of the past – on issues such as the EU, the euro, immigrants, and family (Puleo & Piccolino Citation2022) – while avoiding unrealistic promises regarding the economy and accrediting herself as a credible future PM on the international scene by placing emphasis on being loyal to NATO and supporting the Ukraine war effort.

The electoral law was the same as in 2018 (Chiaramonte, D’Alimonte & Paparo Citation2019), but the cut in MP numbers means that it operated with a few differences. Namely, single-member districts for both chambers are larger, as they were reduced in number. Also, magnitudos for PR seat allocations were altered. This is particularly relevant for the Senate, where the regional distribution of seats yields significant increases in the effective thresholds of many regions. For both chambers, the number of representatives was cut by roughly a third. In the Chamber, they were reduced from 630 to 400. In the Senate, the cut was from 315 to 200. The reduction in the number of MPs has been long proposed by the M5S. It was approved in Parliament by governmental majorities under both the Conte I and Conte II cabinets, and it was finally confirmed by constitutional referendum in September 2020.

Results

The 2022 Italian general election has brought about several remarkable results that made it an outstanding case not only considering the post-World War II (WWII) electoral history of the country but also viewing it in a comparative perspective. To begin with, this election has recorded the lowest electoral participation in a general election with the largest drop in turnout in the Republican era. Within this context of voters’ mounting abstention, those who voted rewarded the centre-right coalition and primarily Giorgia Meloni’s radical-right party. Overall, considering FDI and Lega together, the electoral performance of the radical right was unprecedented in post-1945 Western European electoral history (Emanuele & Improta Citation2022) and has brought about the second consecutive instance of electoral realignment within the centre-right bloc (from FI to Lega in 2018; from Lega to FDI in 2022). This radical-right surge has been counterbalanced by the downfall of the M5S (despite a noticeable recovery during the electoral campaign) and, in continuity with the 2018 election, one of the poorest results ever of the centre-left coalition. Notwithstanding a substantial continuity in the socio-demographic profile of the parties’ electorates, individual vote shifts have been massive, as our estimates indicate that, for the first time ever in the Republican era, the absolute majority of voters actually changed their vote choice between 2018 and 2022. Such individual-level changes have produced two important results at the systemic level: on the one hand, a reconfiguration of party support at the territorial level with the clear emergence of three ‘faces’ of Italy with distinct characteristics and, on the other hand, the third consecutive instance of a highly volatile election with an unprecedented level of aggregate electoral change considering the whole 2013–2022 period. These results are driven by a constellation of long-term and short-term factors that cannot be investigated in great detail in this article. At the same time, we argue that all of them are – to some extent – consequences of the prolonged status of deinstitutionalisation of the Italian party system. The next subsections illustrate these results, while the following discusses its consequences for the party system.

A historic drop in turnout

The first noticeable result of the 2022 Italian general election is certainly the collapse of electoral participation. The turnout rate was 63.9 per cent, a record-low figure for the whole post-1945 era in the country. Most importantly, compared to the previous election in 2018, the 2022 election recorded a 9-point loss, by far the largest ever, with an unprecedented increase of abstainers (+4,500,000 compared to 2018). In terms of geographical differences, Southern regions experienced larger drops (−10.8 points on average) than the North (−7.8) and the so-called Red Belt (−7.4), thus further increasing the already existing gap in electoral participation between the South (57.4 per cent) and the rest of Italy (69.2 per cent).

As shown in , the trend of turnout in Italy since 1948 reveals that a decrease in the participation levels is not new in the country. Turnout started to decline in 1979, with an uninterrupted negative trend in the last 35 years. However, the surprising and, to some extent, worrying insight from this election is the further increase in the acceleration rate of such a decline. Indeed, from 1976 to 2006, we observe a turnout decline of roughly 10 percentage points, with an average drop rate per year of barely 0.3 points. From 2006 to 2018, the yearly drop rate accelerated to 0.9 points. Impressively, from 2018 to 2022, the 9-point loss translates into a remarkable 2.25 yearly drop rate.

Figure 1. Turnout in Italian general elections since 1948.

This trend has deep roots and is the result of a complex set of determinants that cannot be investigated in this article. Certainly, it can no longer be accounted for as a ‘natural’ decline, mainly due to generational replacement, the process through which new cohorts of (mostly less involved) voters gradually replace old cohorts who were socialised after World War II in the golden age of mass mobilisation. Conversely, the decrease in turnout between 2018 and 2022 is also something extraordinary from a comparative historical perspective. The historical reach of this result can be understood properly by considering that turnout change between 2018 and 2022 ranks in the top 10 cases of largest turnout declines in the entire electoral history of Western Europe after World War II (a pool of about 400 Lower House electoral cycles in 20 countries, see Chiaramonte & Emanuele Citation2022).

The massive turnout decline recorded in 2022 contributes to transfiguring the conventional wisdom according to which Italy is traditionally reputed to be one of the countries with the highest rates of electoral mobilisation. For a long time, as displayed in , with a turnout rate around or above 90 per cent, Italy showed one of the highest levels of electoral participation in Western Europe, similar to countries with compulsory voting (e.g. Belgium, Luxembourg). By contrast, if we consider the last general election, the 63.9 per cent of Italy is among the lowest turnout rates in Western Europe, far below the regional average of 70.7 per cent.

Votes and seats

As regards the election results, it is essential to distinguish not only between the Chamber and the Senate but also between the arenas in which the counting of votes is necessary for the attribution of seats to coalitions and single lists: proportional (PR) arena (245 seats at stake in the Chamber and 122 in the Senate), first-past-the-post (FPTP) arena (147 seats at stake in the Chamber and 74 in the Senate) and ‘abroad’ constituency (eight seats at stake in the Chamber and four in the Senate). Hence, approximately two-thirds of the total seats are distributed on the basis of PR representation in multi-member districts (MMDs), whereas about one-third of the total seats are allocated on the basis of the FPTP system in single-member districts (SMDs). However, according to the electoral system, the FPTP and PR arenas of competition are not independent but intertwined. Indeed, candidates in SMDs need to be supported by one or more party lists running for the PR seats. Furthermore, voters give a ‘fused’ vote, meaning that a vote for a party list automatically extends to the SMD candidate backed by that party list and vice versa.Footnote2 Finally, as regards the allocation of PR seats, national thresholds of 3 per cent apply to single party list votesFootnote3 and 10 per cent to coalitions of party list votes (but the votes of coalition party lists receiving less than 1 per cent nationally are not included in their total).Footnote4

summarises the final distribution of votes in the domestic arenaFootnote5 for both chambers and, separately, the distribution of seats for each chamber according to the abovementioned arenas.

Table 3. Results of 2022 Italian general election (Chamber of Deputies and Senate).

The first result emerging from is that the two chambers show very similar results, analogous to what happened in the previous general election of 2018. Indeed, in both cases, the electoral system was almost identical for both branches of the Parliament. Furthermore, this time the electorate was also identical, given that the constitutional reform approved in October 2021Footnote6 entitled citizens under 25 to vote also for the Senate (previously they could vote only for the Chamber).

The results should be analysed separately for coalitions and single lists. As for the former, the winning coalition is the centre-right, with 43.8 per cent of the votes in the Chamber and 43.7 per cent in the Senate, achieving the absolute majority of seats. In 2018, the centre-right coalition also ranked first, but with a lower percentage of votes (under 40 per cent in both chambers) and without achieving the absolute majority. The centre-left coalition ranked second, with 26.1 per cent of the votes in both chambers. Thanks to the presence of the FPTP arena, the advantage of the centre-right was transformed into a larger difference in terms of seats: the centre-right was assigned 237 seats (59.3 per cent) in the Chamber and 115 (57.5 per cent) in the Senate. This represents the highest share of seats got by a coalition since the birth of pre-electoral coalitions in 1994, although the share of votes is not the highest obtained by the centre-right (it was higher in 2001, 2006, and 2008). Clearly, this outcome can be explained by the electoral rules (especially the FPTP mechanism), the (not so) strategic choices made by the main political actors (i.e. centre-right parties ran together to maximise winning chances in SMDs, whereas the others ran divided), and the territorial distribution of votes (i.e. the centre-right coalition was both dominant in the North and had more territorially homogenous support compared to both the centre-left coalition and the M5S). Regarding the disproportionality of the electoral outcome, it should be noted that the Gallagher index (Citation1991) was 7.8: this was the third highest level of disproportionality since 1948 and, comparatively, the fifth highest in Western Europe if we consider only the latest elections. Contrary to the centre-right, the centre-left has been under-represented, getting 85 seats in the Chamber (21.3 per cent) and 44 (22 per cent) in the Senate. The centre-left coalition’s performance was especially disappointing in the plurality arena, where it got only 13 seats (8.8 per cent) in the SMDs of the Chamber and seven seats (9.5 per cent) in the Senate. Outside the two coalitions, the most voted independent list was the M5S, which got around 15.4 per cent of the votes in both chambers, obtaining 52 seats (13 per cent) in the Chamber and 28 (14 per cent) in the Senate. In the plurality arena, the M5S won in 10 SMDs in the Chamber and in 5 SMDs in the Senate. The other independent list that got seats in the Parliament was AZ-IV, with 7.8 per cent of the votes in the Chamber and 7.6 per cent in the Senate. This new centrist party did not win in any of the SMDs, gaining 21 proportional seats (5.3 per cent) in the Chamber and nine seats (4.5 per cent) in the Senate.

As regards single list results, FDI has been the largest party, surpassing the second party, PD, by almost 7 percentage points. The party led by Meloni achieved its best electoral result ever, with around 26 per cent in the Chamber and 25.5 per cent in the Senate. No radical-right party had ever exceeded 20 per cent of the vote in a general election in Italy. FDI got 29.5 per cent of the seats in the Chamber (118 seats) and an even higher share in the Senate (33.3 per cent). As for the other lists within the centre-right, the results for Lega and FI were very similar: the Lega got 8.8 per cent of the votes and 65 seats (16.3 per cent) in the Chamber, whereas FI got 8.1 per cent of the votes and 45 seats (11.3 per cent). In the Senate, the result was very similar. Overall, FDI and Lega, considered together, got the highest percentage of votes ever recorded by the radical right in post-1945 Western European electoral history (Emanuele & Improta Citation2022). The other national party in the centre-right coalition, NM, did not achieve the 3 per cent threshold (only 0.9 per cent), but got seven seats in the Chamber and one seat in the Senate thanks to strategic coalitional agreements during the selection of SMDs candidates.

As regards the centre-left single lists, the party led by Letta achieved the second worst result of its history in percentage terms, getting around 19 per cent of the total vote (19 per cent in the Chamber and 18.6 per cent in the Senate) and 69 seats (17.3 per cent) in the Chamber and 38 seats (19 per cent) in the Senate. The only arena where the PD achieved a satisfactory result was the ‘abroad’ constituency, where it was the most voted party, getting four seats in the Chamber and three seats in the Senate (whereas the joint list among FDI, FI and Lega got only two seats in the Chamber).

The worse performance of the centre-left coalition compared to the centre-right is also due to the bad performance of PD allies: no party achieved the 3 per cent threshold, except EV-SI that got 3.6 per cent in the Chamber and 3.5 per cent in the Senate. +EU (+Europa – More Europe) stopped at 2.8 per cent in the Chamber and at 2.9 per cent in the Senate. Even worse, the other list, IC, got less than 1 per cent, thus not contributing to the coalitional total amount of votes that is used for the allocation of the seats. Nevertheless, in the plurality arena, thanks to coalitional agreements, this party and +EU got a few seats in the Chamber.

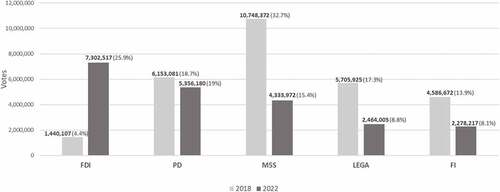

The historic success of FDI is even sharper if we look at , which shows the votes for main Italian parties between 2018 and 2022 with percentage values in parentheses. FDI got only 4.4 per cent of the votes in 2018. This time, despite the sharp decline in turnout, FDI not only significantly improved its performance in percentage points (+21.5 percentage points, which is the second-greatest electoral increase in European history), but it also got almost 5,900,000 more votes. It is the only major party increasing votes between the two elections. Although in percentage terms the PD seems to have performed slightly better than in 2018 (+0.3 percentage points), in reality, it lost almost 800,000 votes. The performance of the other parties is even worse. FI lost 2,308,455 votes (−5.8 percentage points, dropping from the fourth to the fifth position) and the Lega lost 3,241,920 votes (−8.5 points, dropping from the third to the fourth position). Finally, the M5S is the party that suffered the greatest collapse, losing around 6,400,000 votes (−17.3 percentage points) and dropping from the first to the third position.

Territorial fragmentation and the three faces of Italy

As discussed above, the 2022 general election has been characterised by a number of historical electoral outcomes. The turmoil generated at the national level has disarrayed previous territorial alignments, and for the third general election in a row, the electoral map of Italy shows a radically new pattern compared to its historical configuration (see , showing the most voted coalition/party in the SMDs in 2022, compared to 2018 aggregated in the same districts). FDI became the most voted party in the Centre-North, and, together with its centre-right allies, conquered most of the Southern constituencies that the M5S had won in 2018. The former Red Belt (once including Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria, and Marche) experienced a further erosion of the traditional left-wing voting (already in 2018 the most voted party was not the PD but the M5S) and now confirms its historical legacy only around Florence and the Bologna-Reggio Emilia axis.

Figure 3. Most voted coalition/party in the Italian single-member districts (2022 and 2018 compared).

In order to properly understand what happened at the territorial level in the 2022 election, we need to unpack the electoral support for the main Italian parties into different territorial categories that allow us to examine the patterns of continuity and change across two main dimensions: geopolitical areas and municipality size. The former is linked to political subcultures (Trigilia Citation1986; Diamanti Citation2009) and party system nationalisation (Caramani Citation2004; Emanuele Citation2018), while the latter involves the traditional urban-rural division (Rokkan Citation1970; Sellers et al. Citation2013) that is more and more mirrored in the integration-demarcation conflict (Kriesi et al. Citation2006; Hooghe & Marks Citation2018). Consistent with previous studies on the topic (Corbetta, Parisi & Schadee Citation1988; Emanuele Citation2011), we disentangle the Italian territory into three geopolitical areas, the North, the (once) Red Belt, and the South,Footnote7 and five categories of municipality size: tiny municipalities (up to 5,000 inhabitants), small villages (between 5,000 and 15,000), belt towns (15,000–50,000), medium-sized towns (50,000–100,000), and big cities (above 100,000 inhabitants). From the combination of the two dimensions, we obtain 15 categories plus the capital city of Rome, which is in a category of its own.

reports the main parties’ vote share across all these categories and Italy as a whole. Data outline a picture of territorial fragmentation with the emergence of three faces of Italy with rather distinctive characteristics in terms of electoral behaviour. These three faces neither correspond to the three types of voting described long ago by Parisi and Pasquino (Citation1979) nor overlap with the three ‘Italies’ emphasised by the socioeconomic literature on regional subcultures (Bagnasco Citation1977).Footnote8 Rather, the three faces of Italy stem from two old conflict lines (North vs. South and urban vs. rural) that this time are seeming to reconfigure in a new way and, most importantly, assume clearly different political connotations. The three faces are 1) Rural Italy; 2) Centre-North metropolitan Italy; and 3) Southern Italy.

Table 4. Italian parties’ vote share by geopolitical area and demographic size of municipality, Chamber of deputies 2022.

To begin with, conservative parties dominate in rural Italy. The centre-right coalition overcame the centre-left coalition by about 25 percentage points in small villages and 30 points in tiny municipalities. A perfectly monotonical ‘village-oriented’ profile is clearly distinguishable for the three main centre-right parties, which have their respective strongholds in the tiny municipalities and then decrease progressively as demographic size increases. This pattern of electoral support is consistent across the different geopolitical areas but shows its largest differences in the North. Here, the advantage over the centre-left coalition reached 35 points in the tiny municipalities, while in the big cities such advantage was meagre (1.6 points). Interestingly, FDI has a radically different profile compared to its post-fascist ancestors (Italian Social Movement and National Alliance), which showed a predominantly Southern and ‘urban-oriented’ profile (Corbetta, Parisi & Schadee Citation1988; Spreafico & Caciagli Citation1990; Emanuele Citation2011). In 2022, Meloni’s party seemed to borrow the same traditional territorial pattern of voting of the Lega and to replace it in its historical stronghold. Indeed, as for the Lega, FDI’s best performance is recorded in the tiny municipalities of the North (32.1 per cent), while in the Red Belt, the core of the red subculture, FDI had more than a 10-point margin over the PD. Conversely, despite showing the same village-oriented profile, Berlusconi’s party maintains a Southern characterisation, with an overrepresentation in the Mezzogiorno’s villages and poor performances in Rome and Centre-North urban centres, like a typical post-Christian democratic franchise party (Carty Citation2004; Baccetti Citation2007).

In contrast to the right-wing dominance in rural Italy, Centre-North metropolitan Italy is characterised by a large over-representation of the centre-left and, more generally, GAL parties (Hooghe, Marks & Wilson Citation2002). Here the PD achieved its best performance: it replaced FDI as the most voted party both in the big cities of the North (24.5 per cent) and in the urban centres (>50,000 inhabitants) of the Red Belt.Footnote9 The other small centre-left parties (EV-SI, +EU) and even the new liberal, centre-leaning AZ-IV display exactly the same urban-oriented profile, with a perfectly monotonical increase of their vote share from tiny municipalities to big cities. In the metropolitan areas of the Centre-North, these small forces attract a relevant portion of the electorate: their aggregate vote share is 22.6 per cent, with AZ-IV becoming the third most voted party after PD and FDI (12.1 per cent). Similar results were achieved in Rome and in the big cities of the Red Belt, where their aggregate result was close to 20 per cent. In contrast, the three parties got just 8.7 per cent in the tiny municipalities of the South, where their cosmopolitan appeal appears in stark contrast with the socioeconomic and cultural backwardness of that context.

The sharp electoral difference emerging from the comparison between rural and metropolitan Italy provides the centre-right with a structural competitive advantage. Indeed, rural Italy is by far more populated than metropolitan Italy. The two categories of municipalities below 15,000 inhabitants represent 41.2 per cent of the overall valid votes expressed in 2022 against only 22.8 per cent of the big cities, including Rome; Italy is, first and foremost, a country of small municipalities.

The contrasting profiles between rural and urban areas are, to some extent, recomposed in the South, where the M5S is the dominant force. This is not news: in 2018, Giuseppe Conte’s party was already largely over-represented in the Mezzogiorno (Chiaramonte et al. Citation2018), and this pattern was further reinforced in the 2019 EP election (Chiaramonte, De Sio & Emanuele Citation2020). In 2022, the Southern bias of the M5S reached its highest level, with 61.1 out of 100 votes for the party coming from this area, which only represents 35.2 per cent of the valid votes. The Bochsler’s nationalisation score (Bochsler Citation2010) – an index that summarises the territorial concentration of a party’s electoral support – of the M5S is .688, an extremely low level for a non-ethno-regionalist party. This result is in sharp contrast with the original territorial cross-cuttingness of the party, which in 2013 appeared as the most nationalised force of Italy’s post-war electoral history (Emanuele Citation2018, p. 195). The average vote share of the M5S in the South is 26.8 per cent, against a single-digit performance in the rest of Italy (9.3 per cent, with only 7.9 per cent in the North, where it is the fifth party below Lega and AZ-IV). Conte’s party is the most voted in all Southern demographic categories above 5,000 inhabitants, and in the big cities reaches its peak of 31.8 per cent, almost twice as big as the PD.

Overall, the analysis of the territorial patterns of electoral support of Italian parties has outlined the presence of three faces of Italy that show long-term socioeconomic and cultural differences, whose electorates have different needs and ask for different political interventions. These three faces of Italy are now becoming increasingly divergent from an electoral viewpoint. Recomposing such differences will not be an easy task for the Italian political class.

Individual-level dynamics behind the results

Who votes for whom? The socio-demographic characteristics of voters

Who are the voters of the main Italian parties from a socio-demographic standpoint? In order to answer this question, we use individual data from the ICCP Italy 2022 dataset.Footnote10 shows the vote percentages of the parties over the 3 per cent threshold by gender, age group, level of education, and church attendance, shedding light on the electoral preferences of these specific socio-demographic groups.

Table 5. Vote for main Italian parties in the 2022 general election, by sociodemographic characteristics (percentages).

Overall, socio-demographic characteristics do not significantly discriminate among electorates. This is evident for gender: males and females show electoral preferences that are in line with those of the whole sample. However, some socio-demographic groups show party-specific affinities (or aversions) if we look at those groups in which parties’ vote percentages are one standard deviation (3.6) or more away from parties’ vote percentages in the whole sample. The winning party, FDI, is over-represented among voters aged 45 to 54 (31.9 per cent) and among voters with at most a lower secondary education (31.3 per cent), whereas it is under-represented among the youngest voters, aged 18 to 29 (17.3 per cent), among voters with tertiary education (19.2 per cent), and among voters attending church once a month (13.6 per cent). Among the latter, the Lega is also particularly under-represented (3.2 per cent), but in general, the party led by Salvini does not show a distinctive socio-demographic profile. FI, conversely, did particularly well among respondents attending church once a month (23.5 per cent), whereas its performance was poor among not religious respondents (2.9 per cent among those never attending church). As regards church attendance, however, we have to say that the results related to those who go to church once a month might suffer from low reliability given the low numerosity of this category (47 respondents). Furthermore, Berlusconi’s party did quite well among the middle-aged respondents with 12.7 per cent and, to a lesser extent, among the youngest (12 per cent). Contrary to that of the past (Corbetta & Ceccarini Citation2010; Maraffi, Pedrazzani & Pinto Citation2013; Paparo Citation2018), FI’s performance was not good among voters aged 65 or more (although its underrepresentation was not huge, given that its vote percentage in this group was exactly one standard deviation lower than the vote percentage in the whole sample).

On the left, the PD shows an interesting profile as regards age groups: it did well not only among the youngest people (28.4 per cent) but also among the oldest voters, those over 64 (23.4 per cent). Conversely, the PD scored under its average among the other age groups, especially among voters aged 30 to 44 (13.9 per cent) and those aged 55 to 64 (14.1 per cent). Concerning church attendance, the PD did well among churchgoers, attracting 23.2 per cent of those attending church frequently (once a week or more). Conversely, EV-SI performed poorly among churchgoers (on average 0.4 per cent considering also those attending church once a month). In contrast, green-left voters are particularly over-represented among those who never attend church (8 per cent).

Concerning the M5S, it shows a crosscutting profile from a socio-demographic standpoint. Differently from the PD, the M5S performed poorly among assiduous churchgoers (10.8 per cent) and the elderly (9.4 per cent), whereas it did well among middle-aged voters (23.4 per cent among those aged 45 to 54).

Finally, as regards AZ-IV, it did well among voters holding at least a university degree (12.4 per cent), whereas it scored significantly under its average among voters aged 45 to 54 (1 per cent). These are the only relevant socio-demographic features of this new centrist party.

Vote shifts

Finally, in this section we analyse the interchanges of voters which produced the results. We do so by employing data from the ICCP Italy 2022 study.Footnote11 Respondents were asked both what they voted in 2018 and their vote intention for the then upcoming general election. present the cross-tabulations of the two vote choices, revealing the answers to several research questions raised by the comparison between the 2018 and 2022 electoral results: Who are the additional abstainers? Where have Meloni’s new votes come from? Where have the votes of the M5S gone? And where do Calenda votes come from?

Table 6. Vote shifts between 2018 and 2022 in Italy: destination in 2022 of the 2018 voters of the different parties, loyal voters (confirming in 2022 their 2018 vote choice) in bold (percentages).

Table 7. Vote shifts between 2018 and 2022 in Italy: sources from 2018 electorates of the 2022 votes to different parties (percentages).

First, concerning the additional abstainers, for the most part they come from the M5S ranks. Almost a third of 2018 M5S voters abstained in 2022. These are more than 3,000,000 voters. Lega and FI lost large portions of their 2018 electorates as well −21 and 25 per cent, respectively. Although smaller, the outflow towards abstention is also significant for the PD − 12 per cent of its 2018 votes.

Secondly, about new FDI votes, most of them are the effect of an intra-coalition reconfiguration. Both centre-right parties lost a third of their 2018 votes to FDI. This portion is slightly larger than the loyal voters for both. This means that 28 per cent of 2022 FDI voters voted Lega in 2018, while 24 per cent came from Forza Italia. There is also a significant inflow from the M5S, which contributes for 22 per cent of the 2022 FDI votes.

By answering the two previous questions, we have also anticipated where the votes of the M5S have gone. Only a third of 2018 M5S voters confirmed their vote, while 30 per cent abstained, and 15 per cent voted in 2022 for FDI. The outflow towards the PD is also significant, but its size is less than half of the latter.

Finally, the centrist pole has taken most of its votes from the 2018 centre-left front. Namely, 37 per cent of Calenda’s votes in 2022 came from 2018 PD voters, and an additional 4 per cent from its 2018 minor allies. Considering that the portions arriving from FI and M5S are relatively equal (22 and 19 per cent, respectively), the prevalence of former centre-left supporters among Calenda 2018 voters appears quite clear.

There is a further element which emerges from our analysis – the unprecedented overall level of electoral instability registered between 2018 and 2022. Only 46.2 per cent of the whole electorate confirmed in 2022 their 2018 choice, with almost 50% of these stable voters composed of loyal abstainers, namely those who neither went to the polls in 2018 nor 2022. This means that more than half of Italian voters (53.8 per cent) changed their vote behaviour from 2018 to 2022. A similar level of electoral dis-loyalty has never been observed in Italian history, not even in 1994, 2013, or 2018 (De Sio & Paparo Citation2014; De Sio & Cataldi Citation2019).

A deinstitutionalised party system

The result of the 2022 general election has once again highlighted the instability of the Italian party system as far as the balance of power between parties, the pattern of electoral and political competition, and the parties’ programmatic and ideological profiles are concerned.

To begin with, let us observe the trend of the values of Total Volatility (TV) in the Italian general elections from 1948 to 2022 (). As is well known, the index of volatility, calculated according to Pedersen’s (Citation1979) formula, measures the level of the net aggregate (percentages of) vote shifts between two consecutive elections, providing a figure for each election of how much the overall balance of power between the parties has changed since the previous election. In 2022, the value of TV is 34.7, the third highest in the history of Italy since 1948 after those of 1994 and 2013. What is even more important, however, is that such a high value has occurred after two elections, 2013 and 2018, which had already recorded very high TV values, 36.7 and 26.7, respectively. This means that, for at least the last decade, the Italian party system has been going through a phase of profound transformation that does not seem to be reaching an equilibrium.

Figure 4. Evolution of electoral volatility in Italy, Chamber of Deputies (1948–2022).

Furthermore, the sequence of the three consecutive elections held between 2013 and 2022 and the levels of total volatility recorded is unparalleled in any Western European country in the time from the end of World War II to the present day. In fact, as shown in , the mean TV for the 2013–2022 period in Italy is the highest ever, with a gap close to four volatility points to the mean TV of the second and third most volatile sequences, Greece 2012–2015 and Iceland 2013–2017, respectively. In other words, no other Western European country has suffered such high electoral instability in a three-election interval, neither decades ago, nor in more recent times, when multiple (economic, financial, migratory, and pandemic) crises have hit this part of the world with particular virulence; this can be seen from the fact that all the first five sequences of elections with the highest overall volatility began in the last 15 years. In the case of Italy, it is also worth noting that the current sequence characterised by extraordinary levels of volatility started shortly after the closing of another sequence of high electoral turbulence, that of 1992–2001, which developed consistently with the transition between the First and Second Republic and the change in the party system.

Figure 5. Mean values of total volatility for most volatile sequences of three consecutive elections in Western European countries between 1946 and 2022.

Along with the continuing change in the balance of power between parties, the pattern of inter-party competition is also continuing to change. The bipolar setting, centred on the competition between a left-wing pole and a right-wing pole, which had been weakly institutionalised between 2001 and 2008, collapsed in 2013 when a political outsider – the Five Star Movement – became successful. Since then, new and different patterns of electoral competition have emerged and immediately after declined, all characterised by the presence of ‘third poles’, even beyond the M5S, and by the changing party composition of both the centre-left and centre-right coalitions and the changing balance of power within them.

In this context, the restructuring of the party system in a bipolar direction, though incentivised by the existing electoral system, seems far off. The divisions in the centre-left camp have weakened the coalition led by the PD and favoured the emergence of a third centrist pole, made up of Azione and Italia Viva, as well as the Five Star Movement, which has greatly diminished its overall share of votes compared to 2018 but has also become a party with a more markedly left-wing profile compared to the main political orientation of its electorate. From this last point of view, the reconstruction of the alliance between the centre-left parties that includes the M5S (the alliance that, during the last legislative term, had supported the Conte II government born in 2019) would seem possible, and even indispensable to the goal of building an alternative to the right-wing line-up. However, as of today, strong reasons for division between the PD and the M5S persist, which have prevented these parties from running in the same coalition at this election.

The trajectory followed from 2013 to the present by the M5S in terms of its political platform (as it regards, for example, the European issue, with a shift from Euroscepticism to pro-Europeanism), the territorial and ‘ideological’ bases of its electorate (becoming much more ‘Southern’ and, as recalled before, ‘leftist’, after having been far more transversal on both fronts), and alliance strategies (from ‘never with anyone’ to governmental agreements first with the Lega and later with the PD, and even with FI in support of Draghi) illustrate another crucial aspect of the instability we are discussing, namely the change in the political positioning of the parties themselves. After all, similarly to the M5S, in recent years, and even in recent months, we have also witnessed repositioning movements in the case of the Lega, which has transformed itself from an ethno-regionalist party to a national party of the radical right (Albertazzi, Giovannini & Seddone Citation2018; Tarchi Citation2018), although the support that this turn seemed to receive in the previous general election of 2018 and, even more so, in the EP election of 2019, has now been greatly diminished to the point that rumours of going ‘back to the origin’ have already been raised. Finally, in recent times even FDI has toned down some of the more radical positions it took in the past, for example on criticism of European integration; moreover, the exponential growth in support it has received in the last election has deeply changed FDI’s social bases, which may lead to a further adjustment in its policy profile, and its traditional policy preferences may no longer be assured.

Overall, the picture we have drawn returns the image of a deinstitutionalised party system (Chiaramonte & Emanuele Citation2022), that is, one characterised by the persistence over time of high levels of instability and unpredictability. Indeed, if the results of the 2013 and 2018 elections are a clue, the 2022 electoral outcome is proof that the Italian party system has been going through exactly such a process of deinstitutionalisation. As for the foreseeable future, a trend reversal and, thus, a stabilisation, may still be possible. However, should the party system continue to be deinstitutionalised even in the coming years, we will see a progressive decrease in citizens’ satisfaction with democracy and a deterioration of the quality of democracy overall, as empirically demonstrated in similar cases in the past (Chiaramonte & Emanuele Citation2022).

Conclusion

The distinguishing feature of the 2022 general election has been, once again, change. The extent of this change is summarily represented by the value of total volatility we have accounted for in the previous section, which for this election indicates a very significant alteration in the balance of power between the parties and for the last three consecutive elections the highest combined level of instability in the history of Western Europe since 1945.

As we have seen from previous sections, this outcome has occurred as a result of what has happened on both the electoral supply and the demand sides. In terms of the supply of lists and coalitions, there have been some relevant novelties, such as that of Azione-Italia Viva, but above all it has been characterised by an asymmetry in the parties’ strategic coordination, with a pronounced division in the left-wing camp counterbalanced by the union of right-wing political forces. From the demand-side perspective, never before have so many voters decided to abstain as in this circumstance – the lowest turnout since 1948 and the highest decrease of it in the same time period – and, when they did decide to participate, they have often made a choice marked by a discontinuity from that of the 2018 election, as revealed by the analyses of individual vote shifts and parties’ (new) social bases.

In this context of electoral demobilisation and asymmetric competition, the votes obtained by the right-wing coalition were sufficient to translate, thanks to the electoral system, into an absolute majority of seats in both the Chamber of deputies and the Senate, a necessary condition for the formation of a government consisting of the parties of the winning electoral coalition only. In this respect, the 2022 election has once again turned out to be decisive for the first time since 2008, which also saw the victory of the right-wing line-up then headed by Berlusconi.

As for the new government born on 22 October 2022, it will face a number of immediate and serious challenges – curbing inflation, reducing energy costs, passing a budget law, and implementing the EU recovery plan – leaving aside the need for PM Meloni and her party to reassure Europe that they have distanced themselves from their beginnings and also from the very radical anti-European positions they took in the recent past. Indeed, the difficult choices ahead will be a test for Meloni of the cohesion and effectiveness of her government, as well as of its commitment to a mainstream conservative platform.

As for the future of Italian politics, the biggest question mark is whether the electoral and party turbulence that has marked the last decade will continue or not. Looking at the result of the last election, there do not seem to be any signs of re-institutionalisation. Paradoxically, however, it could also well be the new government – now on a ‘watch-list’ – to restore stability to a system that has been suffering from deep and continuous change, by resting on the popular legitimacy obtained through the vote. Though not likely, it will all remain to be seen.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alessandro Chiaramonte

Alessandro Chiaramonte is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Florence, Firenze FI, Italy, where he teaches Italian Politics. He is author or editor of several books on elections, electoral systems and Italian politics. His articles have appeared in West European Politics, Party Politics, South European Society and Politics as well as the main Italian Political Science journals. Among his latest publication is the volume The Deinstitutionalization of Western European Party Systems (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), with V. Emanuele.

Vincenzo Emanuele

Vincenzo Emanuele is an Associate Professor in Political Science at Luiss University, Rome. His research has appeared – among others – in Comparative Political Studies, Perspectives on Politics, West European Politics, Party Politics, South European Society and Politics, Government and Opposition, and Comparative European Politics. He has published Cleavages, Institutions, and Competition. Understanding Vote Nationalisation in Western Europe (1965–2015) with Rowman & Littlefield/ECPR Press and The Deinstitutionalization of Western European Party Systems with Palgrave Macmillan.

Nicola Maggini

Nicola Maggini is an Assistant Professor in Political Science at the Department of Social and Political Sciences of the University of Milan, Milano MI, Italy. He published research articles – among others – in Journal of Common Market Studies, West European Politics, American Behavioral Scientist, South European Society and Politics, Italian Political Science Review and Quality & Quantity. He is the author of Young People’s Voting Behaviour in Europe. A Comparative Perspective (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).

Aldo Paparo

Aldo Paparo is an Assistant Professor at the Political and Social Sciences Department of University of Florence. His main areas of interest are elections and voting behavior – with a particular focus on the local level. His research appeared in Political Psychology, West European Politics, Electoral Studies, South European Society and Politics, Local Government Studies, and Italian Political Science Review – among others. He has also authored chapters in volumes published by Il Mulino and Palgrave Macmillan.

Notes

1. FDI inherited the post-fascist legacy of the Italian right, embodied for 50 years by the MSI (Movimento Sociale Italiano – Italian Social Movement). In 1995 MSI transformed itself into AN (Alleanza Nazionale – National Alliance) (Ignazi Citation1996). In 2007, AN merged with FI to form the PDL. In December 2012, Meloni and a few other MPs opposing the party support for the Monti cabinet split from the PDL and founded FDI. Most of the political personnel comes from the previous parties of the Italian post-fascist right (Puleo & Piccolino Citation2022, p. 20). Meloni herself was a young militant in the MSI in the early 1990s and MP for AN before the merge into the PDL.

2. In the case of a coalition of parties backing an SMD candidate, a vote for that candidate extends pro-quota to all the party lists belonging to the coalition, i.e. proportionally to the total votes each party list gets in that district.

3. A 20 per cent regional threshold, as an alternative to the established 3 per cent national threshold, is set for party lists representing official ethnic minorities.

4. For each coalition, only those lists that have obtained at least three per cent of the vote take part in the internal distribution of seats.

5. It includes valid votes in the Aosta Valley’s SMD (1 seat at stake in each chamber) and in Trentino South Tyrol’s SMDs (6 seats at stake in the Senate).

6. Constitutional law n. 1, 18 October 2021.

7. The South includes all regions of the so-called ‘Mezzogiorno’, including Lazio but with the exclusion of the capital city of Rome, which must be set apart from the rest of the South for socioeconomic and cultural characteristics.

8. Parisi and Pasquino (Citation1979) highlight the existence of three types of voting characterising voting behaviour: opinion voting, identity voting, and vote of exchange. Bagnasco (Citation1977), instead, describes the presence of three Italies: the industrial triangle, the Mezzogiorno, and the so-called ‘third Italy’ consisting of the two subcultural areas of the White and Red Belt.

9. Moreover, the big cities of the Red Belt represent the only category where the centre-left coalition overcame the centre-right one (38.4 against 35.5 per cent).

10. See notes to Table 2 for details.

11. See notes to Table 2 for details.

References

- Albertazzi, D., Giovannini, A. & Seddone, A. (2018) ’“No regionalism please, we are Leghisti!”The transformation of the Italian lega nord under the leadership of Matteo Salvini’, Regional & Federal Studies, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 645–671.

- Baccetti, C. (2007) I Postdemocristiani, Il Mulino, Bologna.

- Bagnasco, A. (1977) Tre Italie. La problematica territoriale dello sviluppo italiano, Il Mulino, Bologna.

- Bochsler, D. (2010) ‘Measuring party nationalisation: a new Gini-based indicator that corrects for the number of units’, Electoral studies, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 155–168.

- Caramani, D. (2004) The Nationalization of Politics: The Formation of National Electorates and Party Systems in Western Europe, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Carty, R. K. (2004) ‘Parties as franchise systems: the stratarchical organizational imperative’, Party Politics, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 5–24.

- Chiaramonte, A. (2015) ‘The unfinished story of electoral reforms in Italy’, Contemporary Italian Politics, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 10–26.

- Chiaramonte, A., D’Alimonte, R. & Paparo, A. (2019) ‘Tra proporzionale e maggioritario. Gli effetti ‘misti’ del nuovo sistema elettorale’, In Il voto del cambiamento. Le elezioni politiche del 2018, eds A. Chiaramonte & L. De Sio, Il Mulino, Bologna, pp. 177–207.

- Chiaramonte, A., De Sio, L. & Emanuele, V. (2020) ‘Salvini’s success and the collapse of the five-star movement: the European elections of 2019’, Contemporary Italian Politics, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 140–154.

- Chiaramonte, A. & Emanuele, V. (2022) The Deinstitutionalization of Western European Party Systems, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- Chiaramonte, A., Emanuele, V., Maggini, N. & Paparo, A. (2018) ‘Populist success in a hung parliament: the 2018 general election in Italy’, South European Society & Politics, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 479–501.

- Conti, N., Pedrazzani, A. & Russo, F. (2020) ‘Policy polarisation in Italy: the short and conflictual life of the “Government of change” (2018–2019)’, South European Society & Politics, vol. 25, no. 3–4, pp. 317–350.

- Corbetta, P. & Ceccarini, L. (2010) ‘Le variabili socio-demografiche: generazione, genere, istruzione e famiglia’, In Votare in Italia: 1968-2008. Dall’appartenenza alla scelta, eds P. Bellucci & P. Segatti, Il Mulino, Bologna, pp. 83–148.

- Corbetta, P., Parisi, A. & Schadee, H. M. A. (1988) Elezioni in Italia. Struttura e tipologia delle consultazioni politiche, Il Mulino, Bologna.

- D’Alimonte, R. (2013) ‘The Italian elections of February 2013: the end of the second republic?’ Contemporary Italian Politics, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 113–129.

- De Lucia, F. & Paparo, A. (2019) ‘L’offerta elettorale fra regole inedite e conflitti vecchi e nuovi’, In Il voto del cambiamento. Le elezioni politiche del 2018, eds A. Chiaramonte & L. De Sio, Il Mulino, Bologna, pp. 13–60.

- De Sio, L. & Cataldi, M. (2019) ‘I risultati di voto e i flussi elettorali’, In Il voto del cambiamento. Le elezioni politiche del 2018, eds A. Chiaramonte & L. De Sio, Il Mulino, Bologna, pp. 127–150.

- De Sio, L., Emanuele, V., Maggini, N., Paparo, A., Angelucci, D. & D’Alimonte, R. (2019) Issue Competition Comparative Project (ICCP), GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA7499 Data file Version 1.0.0.

- De Sio, L. & Paparo, A. (2014) ‘Elettori alla deriva? I risultati di voto e i flussi di voto tra 2008 e 2013’, In Terremoto elettorale. Le elezioni politiche del 2013, eds A. Chiaramonte & L. De Sio, Il Mulino, Bologna, pp. 121–144.

- Diamanti, I. (2009) Mappe dell’Italia Politica. Bianco, rosso, verde, azzurro e … tricolore, Il Mulino, Bologna.

- Emanuele, V. (2011) ‘Riscoprire il territorio: dimensione demografica dei comuni e comportamento elettorale in Italia’, Meridiana - Rivista di Storia e Scienze Sociali, vol. 70, pp. 115–148.

- Emanuele, V. (2015) Dataset of Electoral Volatility and Its Internal Components in Western Europe (1945-2015), Italian Centre for Electoral Studies, Rome.

- Emanuele, V. (2018) Cleavages, Institutions, and Competition. Understanding Vote Nationalization in Western Europe (1965-2015), Rowman and Littlefield/ECPR Press, London.

- Emanuele, V. & Chiaramonte, A. (2020) ‘Going out of the ordinary. The de-institutionalization of the Italian party system in comparative perspective’, Contemporary Italian Politics, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 4–22.

- Emanuele, V. & Improta, M. (2022) ‘La migliore performance della “destra” nella storia dell’Europa occidentale’, CISE, Rome, available online at: https://cise.luiss.it/cise/2022/09/25/la-migliore-performance-della-destra-nella-storia-delleuropa-occidentale/

- Emanuele, V., Maggini, N. & Paparo, A. (2020) ‘The times they are a-changin’: party campaign strategies in the 2018 Italian election’, West European Politics, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 665–687.

- Gallagher, M. (1991) ‘Proportionality, disproportionality and electoral systems’, Electoral studies, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 33–51.

- Hooghe, L. & Marks, G. (2018) ‘Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage’, Journal of European Public Policy, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 109–135.

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G. & Wilson, C. J. (2002) ‘Does left/right structure party positions on European integration?’ Comparative political studies, vol. 35, no. 8, pp. 965–989.

- Ignazi, P. (1996) ’From neo‐fascists to post‐fascists? The transformation of the MSI into the an’, West European Politics, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 693–714.

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S. & Frey, T. (2006) ’Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: six European countries compared’, European Journal of Political Research, vol. 45, no. 6, pp. 921–956.

- Landini, I. & Paparo, A. (2019) ‘Italy: complete overturn among government partners: league doubled, M5S halved’, In The European Parliament Elections of 2019, eds L. De Sio, M. N. Franklin & F. Russo, Luiss University Press, Rome, pp. 173–179.

- Maraffi, M., Pedrazzani, A. & Pinto, L. (2013) ‘Le basi sociali del voto’, Voto amaro: disincanto e crisi economica nelle elezioni del 2013, eds ITANES, Il Mulino, Bologna, pp. 57–70.

- Paparo, A. (2018) ‘Challenger’s delight: the results of the 2018 Italian general election’, Italian Political Science, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–19.

- Parisi, A. & Pasquino, G. (1979) ‘Changes in Italian electoral behaviour: the relationships between parties and voters’, West European Politics, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 6–30.

- Pedersen, M. N. (1979) ‘The dynamics of European party systems: changing patterns of electoral volatility’, European journal of political research, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–26.

- Puleo, L. & Piccolino, G. (2022) ‘Back to the post-fascist past or landing in the populist radical right? The brothers of Italy between continuity and change’, South European Society & Politics, pp. 1–25.

- Rokkan, S. (1970) Citizens, Elections, Parties, Universitetsforlaget, Oslo.

- Sellers, J. M., Kübler, D., Walter-Rogg, M. & Walks, R. A. (eds) (2013) The Political Ecology of the Metropolis: Metropolitan Sources of Electoral Behaviour in Eleven Countries, ECPR Press, Colchester.

- Spreafico, A. & Caciagli, M. (1990) Vent’anni di elezioni in Italia: 1968-1987, Liviana, Padova.

- Tarchi, M. (2018) ‘Voters without a party: the “long decade” of the Italian centre-right and its uncertain future’, South European Society & Politics, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 147–162.

- Trigilia, C. (1986) Grandi partiti e piccole imprese. Comunisti e democristiani nelle regioni a economia diffusa, Il Mulino, Bologna.

- Tronconi, F. & Valbruzzi, M. (2020) ‘Populism put to the polarisation test: the 2019–20 election cycle in Italy’, South European Society & Politics, vol. 25, no. 3–4, pp. 475–501.