ABSTRACT

Focusing on Southern Europe during the sharp electoral rise of radical left parties (RLPs) (2008–2020), this article identifies a post-industrial pattern of class support for the radical left. Leveraging survey data, it shows class support for the radical left is linked to a horizontal distinction in the labour market based on work logic. RLPs attract mostly those working in face-to-face service jobs, lower-grade associate professionals voting based on cultural and economic preferences, and unskilled routine workers voting out of economic preferences. Radical left support in post-industrial Southern Europe is thus stronger among service workers and segments of the professional middle classes than among production workers.

Introduction

The transition to post-industrial economies, underpinned by the major socioeconomic transformations provoked by globalisation, the expansion of the welfare state, educational upgrading or the tertiarization of occupational structures, provoked a realignment of partisan preferences throughout most advanced economies of the Western hemisphere (Beramendi et al. Citation2015; Kriesi et al. Citation2008). While considerable attention has been paid to how these changes have shifted the nature of support for mainstream and, particularly, radical right parties (Bornschier & Kriesi Citation2014; Oesch & Rennwald Citation2018), the impact of post-industrialisation on support for radical left parties (RLPs) has, however, been insufficiently explored by previous research.

The argument for a post-industrial pattern of support for RLPs is twofold. First, the notion that there is an underlying horizontal division in the labour market based on work logics. In post-industrial societies, occupations have become more diverse, for example with the rise of the information technologies (IT) and business sectors (Oesch Citation2006), while voting behaviour has become more influenced by individual experiences rather than group commitments (Thomassen Citation2005). This has significant implications for the debate on class voting, as different occupations carry with them widely distinct lived experiences, e.g. contact with different types of people (or lack thereof) and different goals (e.g. maximising profit vs. service in the public sector), with significant impacts on political preferences (Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2014). It is, however, unclear from previous research whether this dimension of work logic can in fact shape support for the radical left.

The second is the impact of a vertical distinction, based on marketable skills and logics of authority. This dimension refers to one’s discretion over one’s own work and the work of others, as well as the competence, capacity, and power associated with each occupation (Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2014). Logics of authority create a rift between lower-grade and higher-grade occupations, underpinned by differences in marketable skills (e.g. skilled vs. unskilled workers) and levels of discretion (e.g. professional vs. associate professional). Demand for skilled over low-skilled labour has been a distinctive feature of post-industrial societies, which has made it increasingly difficult for workers with low levels of education and working in routine jobs to maintain standards of living (Oesch Citation2006). Can RLPs’ appeals for stronger state intervention in the economy drive this group to vote in large numbers for these parties? At the same time, attitudinal changes in European societies have realigned parts of the culturally progressive middle-classes with left-wing parties (Charalambous & Lamprianou Citation2017). For some higher-grade positions, being part of the middle-class has not translated into significant improvements in income or living standards, which often means that they have left-wing positions on the economy and socially liberal attitudes (Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2022). Considering the increasing adoption of new politics issues by RLPs (e.g. environmentalism, anti-racism) alongside their traditional economic agenda (Fagerholm Citation2017), can this group of middle-class voters also be a significant part of the radical left electorate?

Against this background, this article attempts to understand whether there is a post-industrial pattern of class support for the radical left, focusing on Southern Europe. The political scene in this region has been fundamentally altered by the rise of parties such as SYRIZA (Coalition of the Radical Left, Greece) and Podemos (We Can, Spain), and with RLPs leading governments (Greece, 2015–2019), joining government coalitions (Spain, 2019-currently) or lending support to minority governments (Portugal, 2015–2019). At the same time, unlike in most other European countries, the more traditional the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) and the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) persist as relevant electoral forces in this region. This provides a unique context to understand whether and how a new form of political alignment can take place amidst the significant electoral strength of the radical left.

Drawing on data from the European Social Survey (ESS) and the Hellenic National Election Study (ELNES), this article analyses the extent to which occupational class explains support for RLPs in Portugal, Spain and Greece from 2008 to 2020. Building on Oesch’s (Citation2006) class schema to examine horizontal (work logic) and vertical (cross-cutting differences based on skill levels) class effects on voting, this article shows that workers who have daily contact with other people as part of their job, usually in a service logic (interpersonal workers) are significantly more likely to support RLPs. These parties’ support is also firmly grounded in sectors of the professional middle classes (technical and sociocultural professionals) and, to a lesser extent, in the ‘new working-class’ of service workers. In contrast, they receive less support from the traditional working-class of production workers.

Radical left parties and the class cleavage

The changing nature of radical left parties and political alignments

The radical left is a party family located to the left of social democracy. The former opposes the current social, economic and political status quo (March & Mudde Citation2005). RLPs are characterised by their rejection of the socioeconomic structures of contemporary capitalism and their promotion of collective rights and wealth redistribution (Charalambous Citation2022). Their critique of capitalism can nevertheless range from strong anti-capitalist rhetoric to a more reformist neo-Keynesian approach (March & Keith Citation2016).

RLPs have historically accommodated two different strands of left-wing radicalism with distinct connections to the class cleavage. The communists, on the one hand, were built as parties of the working-class; they attempted to mobilise workers through deep connections with the labour movement and the use of anti-capitalist appeals (Bartolini Citation2000; March Citation2011). They attracted mostly production workers and employed farmers, but also a significant number of middle-class voters with progressive social views and economically interventionist preferences (Bartolini Citation2000). Left socialists, on the other hand, can be traced back to the radical movements of the Long ’68, which inspired a wave of new left parties that stressed post-materialist issues typical of modernisation, such as environmentalism and feminism (Charalambous Citation2022). Because of their ideological nature, these new left parties have a considerable amount of new middle-class groupsFootnote1 among their voters, as well as younger and more educated voters (Gomez, Morales & Ramiro Citation2016).

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, RLPs went through significant ideological, organisational and strategic changes (Chiochetti Citation2017). During the 1990s, many communist parties either disbanded or went through significant changes, with many of them being incorporated in broader radical left alliances (March Citation2011). This trajectory has solidified their position in European party systems as actors with strong left-wing preferences in both the cultural and economic axes of the two-dimensional political space typical of post-industrial societies, focusing on combating the negative effects of neoliberalism and globalisation (e.g. unemployment, precarity), while also adopting a stronger post-materialist outlook on political conflict (Fagerholm Citation2017). This modernising trend has however been resisted by some of the more orthodox communist parties, who attempted to maintain a traditional form of working-class mobilisation through trade unions and resisted the turn towards a post-materialist agenda (Keith & Charalambous Citation2016).

These changes motivated a series of studies aimed at explaining how RLP voters have evolved during this period (e.g. Gomez & Ramiro Citation2022; Ramiro Citation2016; Rooduijn et al. Citation2017). There remain, however, some gaps concerning the role of class. First, while previous research has argued that support for RLPs is shaped by self-identification with the working class (Ramiro Citation2016) and by belonging to specific social groups (Gomez & Ramiro Citation2022), the impact of a horizontal distinction based on work logic and a vertical distinction based on levels of skill and authority relations within the workplace has not been directly addressed. Furthermore, while occupational experiences play a key role in the development of political attitudes in post-industrial societies (Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2014), studies have also not addressed the mediating role of political attitudes, such as pro-egalitarian demands for economic redistribution and upholding minority rights on class support for the radical left. This can be particularly relevant for this party family, considering that the RLP vote is highly ideologically-driven (Gomez & Ramiro Citation2022).

The argument for work logic shaping political preferences can be traced back to early works in sociology of occupations, which argued that daily work experiences (e.g. existence of strict hierarchies or the possibility of exercising self-direction) are critical in shaping personality, values and behaviours (e.g. Kohn & Schooler Citation1982). In post-industrial societies, as traditional class allegiances and partisan alignments decline (Thomassen Citation2005) and the labour market became more fragmented, for example, with the growing number of individuals employed in the service sector (Oesch Citation2015), work logic has been highlighted as an important factor in the formation of political attitudes, particularly on cultural issues (Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2014).

Work logic can furthermore be expected to drive support for the radical left, particularly among interpersonal employees. Interpersonal employees are an increasingly important feature of post-industrial societies. This work logic encompasses those working in face-to-face service jobs, dependent primarily on social skills and contact with other people, and in which loyalty to the organisation/company (or, many times, the state) is blurred by a direct attendance to customers’/patients’ demands (Oesch Citation2006, p. 63). Because these occupations deal with human individuality (e.g. health and education sectors), are heavily reliant on communication, and focus on people-work (e.g. direct care of children or elderly), these employees are more likely to hold culturally progressive attitudes and accept diversity and solidarity as principles of life (Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2014). This brings them closer to a radical left increasingly focused on a post-materialist agenda, particularly those parties which stem from the new left tradition (Gomez, Morales & Ramiro Citation2016). Simultaneously, interpersonal employees’ culturally progressive worldview, fostered through working in an interpersonal work logic, also dovetails with the self-transcendent nature (prioritising concern for others over individual power and achievement) of radical left voting (Gomez & Ramiro Citation2022) and the positive conception of human nature common to all traditions of radical left parties and movements (Charalambous Citation2022).

In terms of the vertical distinctions within the labour market, literature on political alignments has argued that changes in occupational structures in post-industrial European societies, propelled by deindustrialisation and globalisation, have reinforced the demand for skilled (e.g. IT, business, education) over low-skilled labour (e.g. traditional blue-collar jobs, service workers) (Oesch Citation2015). This vertical distinction captures the different levels of dispositional capacity, competence, and authority in each occupation, attached to the management of scarce financial, material, and human resources (Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2014). It is unclear how such division affects RLP support, but previous literature suggests a differentiated impact, through cultural and economic attitudes, depending on one’s position in the social structure. Higher-grade positions are usually associated with a view of organisations and society that is more in line with resource allocation and material incentives. A position of organisational gatekeepers makes them more prone to espouse pro-market economic views than lower-grade positions (Ares Citation2020).

However, higher levels of autonomy and discretion are usually associated with preferences towards a more libertarian governance and a more inclusive conception of citizenship, which leads individuals in higher-grade positions to present distinctively socially liberal preferences on cultural issues when compared to individuals in lower-grade positions (Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2014). This pulls lower-grade employees towards the left on economic issues but pushes them away from the left on cultural ones and does the reverse for the higher-grade positions. It can be expected, however, that RLPs will attract more support from some groups than others. First, unskilled workers face a more hostile labour market than skilled workers, a feature which might lead them to support RLPs because of economic concerns. Second, even among the higher-grade positions, social differences are substantial. While these positions entail high levels of education and are commonly associated with a progressive cultural worldview, associate professionals are more likely to have a lower income and a more unstable employment situation than professionals (e.g. an associate nurse compared to a medical doctor) (Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2022). This might drive associate professionals to support RLPs due to both economic and cultural concerns.

Southern European radical left parties and the class cleavage

Southern Europe presents a relevant region for the study of class in the electoral support for the radical left for two main reasons. First, the radical left has been particularly electorally successful in this region (), especially since the Eurozone crisis. This crisis provoked a sea-change in political alignments in the region, from which the radical left was the main beneficiary (Lisi Citation2019). Austerity measures implied a series of institutional and social changes (e.g. in labour market policies), which disproportionately hit some social groups (Moreira et al. Citation2015). They furthermore provoked a deterioration of living conditions and public services, whilst being implemented under large-scale protests (della Porta Citation2012).

Figure 1. Electoral results of RLPs in Portugal, Spain and Greece (2004–2020).

The Southern European radical left includes both parties from the new left tradition, more recently created, which have a stronger post-materialist component (e.g. SYRIZA, Podemos, BE), and, on the other hand, the more orthodox communist parties, which retain the ideological and organisational apparatus of Marxism-Leninism and a more traditional Marxist approach to political conflict centred on economic concerns (PCP and KKE) (Keith & Charalambous Citation2016). Since the Eurozone crisis, the most notable cases of electoral success are SYRIZA and Podemos (). The first became the most voted party in the 2015 and lead a coalition government in Greece (2015–2019), while the second played a key role in breaking Spain’s two-party system the first time it ran in a national election (2015) and became a coalition partner of the socialists in Spanish government (2019–2023).Footnote2 Even in Portugal, where RLP growth was more restricted, BE (Left Bloc) was able to surpass its best electoral results recorded to date on two occasions (2009 and 2015). The party went on to support, alongside the communists (PCP), a minority government of the Socialist Party (2015–2019), an unprecedented move in Portuguese politics since democratisation. The clear electoral outliers here appear to be the communist parties in Greece (KKE) and Portugal (PCP), which presented modest gains on some occasions and small drawbacks in other elections. Despite this, they remain two of the very few cases of relevant communist parties in post-Soviet Europe.

The second reason Southern Europe is a relevant region for this study is that Southern European countries differ in their social composition from most Western European countries. The former have a larger combined size of production and service workers, a relatively smaller size of the salaried middle-classes (socio-cultural specialists, technical professionals and managers) and a larger number of small business owners (Bulfone & Tassinari Citation2021). At the same time, Southern Europe presents significantly higher levels of precarious employment, unemployment, and labour market instability than other European regions (e.g. Narotzsky Citation2020). This factor is particularly relevant, as types of employment and income levels also play an important role in activating political preferences in post-industrial societies (Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2022).

Hypotheses

One of the central arguments of this article is that the impact of class can be understood horizontally, that is in terms of the effect of work logic. As argued previously, work logic mainly impacts cultural attitudes and interpersonal employees – those working on a face-to-face service logic (e.g. teachers, shop assistants), focused on people-work and heavily reliant on communication. They are more likely to hold culturally progressive views than those in other work logics (Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2014).

RLPs have been at the forefront of advancing a post-materialist agenda in Southern Europe. Their most successful battles have been around ‘new politics’ issues, mainly by proposing legislation on issues such as domestic violence or gay marriage, and building majority coalitions around such proposals (Charalambous Citation2022, p. 167). Even the communist parties have maintained strong appeals for investment in culture and upholding peace which resonate closely with these progressive stances (Fagerholm Citation2017). Thus, employees in the interpersonal work logic may align with the radical left. In contrast, there is no reason to expect the same effect for technical or organisational work logics, which are usually more oriented towards the goals of the enterprise and more influenced by the vertical distinction (e.g. between workers and managers), where economic conflicts likely remain more central than the sociocultural dimension, or for the self-employed (independent work logic), where self-reliance becomes a guiding principle. This leads to the first hypotheses.

H1A:

Employees in the interpersonal work logic are more likely to support a RLP than those working in a technical, organisational or independent work logic.

H1B:

Interpersonal employees’ support for RLPs is mediated by cultural attitudes.

Beyond the horizontal dimension, this research examines whether a vertical distinction based on levels of skill and relations of authority within the workplace in post-industrial labour markets shapes support for RLPs. This vertical distinction could arguably drive both a cultural division between more culturally progressive yet more economically liberal middle-class professionals, and more socially conservative yet more economically left-wing workers (Ares Citation2020; Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2014). Workers with lower levels of skill find it hard to compete in the education-intensive labour market of post-industrial societies compared to the skilled members of the working class. This also coincides with the argument that the lowest social strata are more likely to hold a radical left ideology (Visser et al. Citation2014). Simultaneously, while higher-grade managerial and professional positions usually entail a view of society more in line with organisational gatekeeping and resource management (Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2014), that is arguably not the case for the lower-grade (associate) professionals. The latter can continue to experience a modicum of economic and labour instability which might lead them to espouse left-wing economic views, just as their experience as highly-educated professionals might also lead them to espouse progressive cultural views. This leads to the second set of hypotheses.

H2A:

Associate professionals and unskilled workers are more likely to support a RLP than skilled workers.

H2B:

Associate professionals’ support for RLPs is mediated by economic and cultural preferences.

H2C:

Unskilled workers’ support for RLPs is mediated by economic preferences.

This research also examines whether Southern European RLPs have been able to attract specific occupational groups. These groups are the combination of horizontal and vertical class distinctions. Additionally, they have played distinct historical and sociological roles both due to their participation in the organised labour movement (e.g. trade unions) and to the strategies that parties have developed to attract them. This fosters the development of strong identities and distinct experiences which can impact individuals’ preferences and experiences beyond their work logic and relations of authority within the workplace. Most notably, the traditional working-class of production workers (lower-grade technical workers) have historically been the backbone of centre left and radical left parties (Bartolini Citation2000). This class was however negatively affected by the socioeconomic changes of globalisation and the move towards post-industrial societies. It has resisted the process of attitudinal change and has migrated towards the radical right in some Western European countries (Oesch & Rennwald Citation2018). While the radical right is a fairly recent phenomenon in some Southern European countries (e.g. Portugal and Spain), the culturally conservative reaction of part of this traditional working-class to the movement towards post-industrial economies has likely put it at odds with a radical left that has been at the forefront of advancing a post-materialist agenda (e.g. same sex marriage, abortion) (Charalambous Citation2022). Furthermore, the limited strength of socialisation mechanisms between the working-class and left-wing movements may have furthered this trend, considering both that union membership in Southern Europe has been structurally low (Sánchez-Mosquera Citation2023) and that many of the most electorally successful RLPs in this region, such as SYRIZA, BE or Podemos are relatively recent parties that were created in the post-industrial era and never had strong connections with traditional labour movements (Charalambous Citation2022).

A central feature of post-industrial societies is however the emergence of a new working-class of service workers. These workers are the clearest example of a class experiencing precarity and instability in the labour market typical of post-industrial societies (Antunes Citation2018), particularly in a Southern European region marked by labour market precarity and the rapid expansion of service activities such as tourism (Narotzsky Citation2020). Service workers are thus expected to be highly likely to support RLPs, as their interests coincide with the political offer put forward by these parties, focused on combating the exact same socioeconomic issues service workers are experiencing, under the parties’ broader umbrella of resistance against neoliberal globalisation (Lourenço Citation2022). Furthermore, as Southern European RLPs have sought to diversify their links with social movements by going beyond the traditional working-class and core party members (Tsakatika & Lisi Citation2013), they have also likely strengthened their connection with service workers.

At the same time, the expansion of professionals working in the service sector, the sociocultural professionals (e.g. teachers, medical doctors, social workers), is also one of the distinctive features of the post-industrial occupational structure (Oesch Citation2006). This occupational group is one of the main actors in the electoral re-alignment of post-industrial societies. It comprises unique occupations which simultaneously require high levels of education (usually associated with left positions on cultural issues) but provide lower income than other high-grade positions (thus also favouring left-wing positions on economic issues) (Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2022). Sociocultural professionals’ unique position in the labour market is thus commonly associated with progressive economic and cultural preferences, further fuelled by their experience as employees in an interpersonal work logic (Kitschelt & Rehm Citation2014). They vote in large numbers for left-wing parties, particularly for the Green left (Charalambous & Lamprianou Citation2017). As RLPs have increasingly adopted a post-materialist agenda (Fagerholm Citation2017), they have also attracted many voters from this occupational group (Gomez & Ramiro Citation2022). The absence of strong Green parties in Southern Europe might have furthered the connection between this occupational category and RLPs. This leads to the last hypothesis.

H3:

Service workers (the new working class) and sociocultural professionals are more likely to support a Southern European RLP than production workers (the traditional working class).

Lastly, it is worth considering how the effect of class may vary across different types of parties within the radical left. As noted before, Southern European RLPs come from two distinct historical and ideological traditions. The more recently created new left parties have a distinct focus on the new politics agenda (e.g. minority rights) and a more moderate economic program (United Left, BE, SYRIZA, Podemos). The communist parties, created in the 1920s, have persisted as mass organisations with deep-rooted connections to the labour movement throughout their history, and a more traditional left-wing platform centred on economic concerns. Both communist and new left parties and voters share, despite these ideological divergencies, an unwavering commitment to rectifying inequalities and a positive conception of human nature (Charalambous Citation2022, pp. 33–34), as well as a tendency for self-transcendence, that is prioritising other people’s concerns over one’s own (Gomez & Ramiro Citation2022). This suggests that work logic, by spurring culturally progressive attitudes, and authority relations, through a combination of economic and cultural attitudes, can drive support for both new left and communist RLPs. Nevertheless, this alignment is arguably clearer for those parties who follow a clear socially liberal agenda (new left) than those who retain a more traditional Marxist one (communists). Beyond these ideological distinctions, historical legacies may also play a role. Communist parties’ longer presence in Southern European countries has allowed them to establish strong connections with trade unions, particularly through influential workers’ confederations, mainly composed of male, older workers with standard employment in large factories (Sánchez-Mosquera Citation2023). This might drive these parties to maintain stronger support from specific social groups, particularly production workers, than their new left counterparts. Similarly, electoral specialisation can further this trend – competition between new left and communist parties at the national level can further differences in terms of their electorate, by entrenching their support among particular social groups. However, as noted earlier, the main mechanisms through which class divisions based on work logic (horizontal) and skills and logics of authority (vertical) apply to both new left and communist RLPs, so the main analysis of this article considers the two types of parties jointly.

Research design

Period of analysis and case selection

This research is based on repeated cross-sectional surveys focusing on support for RLPs in three Southern European countries from 2008 to 2020: Portugal, Spain, and Greece. This time frame marks a particularly turbulent political period, with the impacts of the Eurozone crisis (the three countries going through bailout programmes, starting with Greece in 2010), the migration crisis and the emergence of new waves of social protest (della Porta Citation2012). It was also a period of significant changes in political alignments (Lisi Citation2019), from which the radical left was the main beneficiary, with RLPs entering (Spain and Greece) and supporting (Portugal) governments in all three countries for the first time in decades.

In terms of case selection, this paper considers all RLPs with parliamentary representation in Portugal, Spain and Greece during the period of analysis, following the conceptualisation of March (Citation2011) (see Table A1 of the Online Supplemental Material for the list of parties). Although other Southern European countries, such as Cyprus or Italy could be included as part of the Southern European region, the three countries outlined above share a set of common characteristics – European Union (EU) membership, similar political cultures and reasonably similar political systems (McLaren Citation2008) – which are useful for the purpose of a comparative analysis of voting behaviour. During the Eurozone crisis, Portugal, Spain and Greece also received bailout programmes to deal with crisis, during which a series of harsh austerity measures were implemented.

While the electoral rise of the radical left was a common trend in the three countries during this period, several substantial differences between the three remain. The Portuguese party system has remained fairly stable in the aftermath of the Eurozone crisis, while the Spanish and, particularly, the Greek underwent major changes (Lisi Citation2019). The traditional centre-left has virtually disappeared in the Greek case after the sharp decline of PASOK, while remaining a relevant force in Portugal and Spain. Similarly, the radical right appeared for the first time in Portuguese and Spanish parliaments only recently (Citation2019), while several radical right parties have been relevant forces in Greek politics for decades (e.g. LAOS and Golden Dawn).

There are also substantial differences at the party and country-level. On the one hand, two RLPs compete at the national level in Portugal (PCP and BE) and Greece (SYRIZA and KKE). PCP and KKE, two of the few remaining cases of electorally relevant communist parties in post-Soviet Europe, have maintained significant ideological orthodoxy and a rigid organisational structure since the fall of the Berlin Wall (Keith & Charalambous Citation2016). In contrast, BE and Syriza are more recent parties, created in late 1990s and early 2000s, following a left-libertarian tradition which has sought to detach itself more clearly from Soviet heritage and adopt a new progressive agenda focused on social rights and post-material values (Charalambous Citation2022). On the other hand, in Spain, while two RLPs have also competed in one election in 2015 their trajectory is considerably different. United Left, while the heir of the Spanish Communist Party, has followed a decades-long path of modernisation and moderation. Podemos, running for the first time in a national election in 2015, was created out of the mass protests against austerity measures in Spain, presenting a distinctively populist character. These parties created the coalition Unidas Podemos in 2016 (UP, United We Can) and in 2023 joined the Sumar coalition, alongside other left and green parties. Podemos has since left the coalition.

Data and methods

Individual-level voting data was retrieved from rounds 4–10 of the ESS dataset (ESS Citation2022). ESS covers the whole period, countries and parties relevant for this analysis, apart from Greece in the period from 2012 to 2018. Considering this, ESS data is merged with the 2012 and January 2015Footnote3 rounds of the ELNES dataset (ELNES Citation2012, Citation2015).

In ESS and ELNES, respondents are asked which party they voted for in the last national election. This provides the main dependent variable, which separates those who voted for a RLP, and those who voted for any other party (or cast a blank/null vote). To account for internal differences within the radical left, a second dependent variable is created, separating the vote for new left parties (Syriza, BE, and Podemos equals 1, vote for other parties, including PCP and KKE, equals 0), and the vote for communist RLPs (vote for PCP and KKE equals 1, vote for other parties, Syriza and BE included, equals 0). For this second dependent variable, observations from the Spanish case are removed, due to the absence of a relevant communist party running in a national election.

The main independent variable is voters’ class position – their position in the labour market. This is then subdivided in two main variables, work logic and levels of skill, following Oesch (Citation2006) (see ). Work logic is a variable with four categories. Independent work logic encompasses any type of self-employed occupation. Organisational work has a clear command structure that corresponds to a career sequence, where authority and orientation towards the organisation play a key role in work experiences. In the technical work logic, one’s job identity stems less from the organisation, and more from belonging to a scientific community or trade. Lastly, the interpersonal work logic is based on a face-to-face service logic, where individuals usually stand outside of a direct line of command and depend primarily on social skills, and loyalty towards the organisation is blurred by direct contact with clients, patients and petitioners.

Table 1. The 8-class schema based on work logics and levels of skills.

There is also a cross-cutting vertical division of skill, which divides occupational groups in four categories. Professionals include those employed in higher-grade positions, almost invariably demanding higher education, and whose jobs have a high level of discretion and authority attached to them (e.g. medical doctors, finance managers). Associate professionals also have highly-qualified occupations, but whose levels of discretion and autonomy are relatively lower than professionals (e.g. associate nurses, social workers). Skilled routine are workers who do routine work, which demands some sort of craft and vocational training (e.g. office clerks, police officers), and unskilled routine workers are those in occupations centred on routine tasks which seldom demand any sort of training (e.g. receptionists, cleaners).

The 8-class schema is built using the combination of the work logic and skill level distinctions (see Table A2 of the Online Supplementary Material). To construct this class-schema, the vertical distinction is collapsed, by combining professionals and associate professionals into one category (higher-grade) and skilled and unskilled routine workers into another (lower-grade). The higher-grade occupations include independent professionals such as self-employed dentists or lawyers, managers such as personnel managers or administrators, technical professionals such as IT specialists or architects and sociocultural professionals, such as doctors, teachers, or social workers. The lower-grade classes include small business owners such as shop owners and farmers, production workers such as assemblers and carpenters, service workers, such as shop assistants and waiters, and clerks such as secretaries and receptionists.

Survey respondents are allocated to one of these categories based on their current job. Three main sources of information are used to build the categories: employment status (separating self-employed from employees), the number of employees (separating large employers with 9+ employees from small business owners with 0–8 employees) and detailed occupational information, following the professional categories of ISCO (International Standard Classification of Occupations), provided by the International Labour Organisation and present in the ESS [‘isco08’ (ESS rounds 4–10] and ELNES [variables ‘D11’ (2012) and ‘D11new’ (2015)].

The hypotheses are tested through multilevel logistic regression modelling – individuals (level 1), nested within countries (level 2), nested within years (level 3) –, followed by the calculation of average marginal effects. It could be argued that considering the small number of countries (three), a logistic regression model is more appropriate than a multilevel model (e.g. Stegmueller Citation2013). The main analyses of this article have been duplicated using a standard logistic regression model, and the findings remain unchanged (see Table A12 and Figure A2 of the Online Supplementary Material). The analyses control for several other variables which also shape support for the radical left. First, a set of sociodemographic variables: age (continuous variable based on year of birth), gender (binary variable separating man and woman), education (three-category variable, separating individuals with less than secondary education, secondary or vocational education, and university degree) and employed in the public sector (yes or no). Second, a set of political attitudes and issue positions which the literature has shown to be highly correlated with radical left support (e.g. Gomez & Ramiro Citation2022; Ramiro Citation2016): trade union membership (yes or no), religious attendance (rarely/never or frequently) and satisfaction with democracy (continuous variable from 1–very dissatisfied to 4–very satisfied). All models include weights and country and year dummies. The main results are robust to different model specifications around these variables for example, if excluding satisfaction with democracy (see Tables A12 and A13).

Lastly, to account for the mediating effect that political attitudes play in the effect of class on RLP support, variables on cultural positions and economic positions are added to the baseline models. The indicator for citizens’ positions on cultural issues is constructed by considering, first, positions towards immigration (considering the question on whether ‘national culture is enriched or undermined by the presence of immigrants’) and the LGBT community (‘Gays and lesbians are free to live as they wish’). Both items, based on an ordinal five-point scale (1-disagree strongly to 5-agree strongly), are merged into a single variable for position on cultural issues. The indicator for positions on the economy is based on the answer to the question on whether ‘the government should reduce differences in income levels’, based on a five-point ordinal scale (1-disagree strongly to 5-agree strongly).

Results

presents vote distribution for Southern European RLPs based on work logic (horizontal lines) and levels of skill (vertical lines) (see Figure A1 and Table A3 of the Online Supplementary Material for vote distribution based on Oesch’s 8-class schema and party-level vote distribution, respectively). In terms of work logic, data confirms the assumption that interpersonal employees − 28 per cent of the working population – vote above average for the radical left (16.2 per cent average vote). In contrast, RLPs receive below average support from other work logics, particularly the self-employed (independent work logic) and technical employees, while support among organisational employees (14.2 per cent) is slightly above average. In terms of the vertical distinction based on skill and levels of authority, radical left support is slightly below average for skilled routine workers (13.1 per cent) and slightly above average among unskilled routine workers (14.1 per cent) and associate professionals (14.3 per cent). In contrast, RLP support is clearly above average in the case of higher-grade professionals (16.9 per cent).

Table 2. Vote for radical left parties in Southern Europe by work logic and levels of skill (2008–2020) (in percentages).

Combining both dimensions (work logic and marketable skills), RLP support is higher among professionals in the interpersonal (21.7 per cent) and technical (19 per cent) work logics, but also among unskilled routine workers in the organisational (19.6 per cent) and interpersonal (16.9 per cent) work logics. The groups which vote disproportionately less for the radical left are professionals and semi-professionals in the organisational work logic (11.1 per cent and 10.2 per cent, respectively) and skilled and unskilled routine workers in the technical work logic (11.2 per cent and 10.6 per cent, respectively). In terms of Oesch’s 8-class schema (Figure A1, Online Supplementary Material), this means that middle class professionals (sociocultural and technical specialists) are the classes which more disproportionately vote for the radical left (around 19 per cent RLP support for both occupations), whereas production workers – the largest group, making up 29 per cent of the working population – vote clearly below average for RLPs in Southern Europe (11 per cent).

presents the tests of the association between these different dimensions of class and support for RLPs after the inclusion of several control variables, while also testing for the mediating effects of cultural and economic attitudes (see Tables A12 and A13 for different model specifications). Model I tests the association between work logic and radical left support. Descriptive statistics showed that interpersonal workers vote more than other work logics for the radical left, as posited by H1A. To further substantiate this claim, interpersonal employees were established as a reference category in the multilevel logistic regression models. The first model (Ia), where the effect of work logic is controlled for sociodemographic variables, trade union membership, work in the public sector and religiosity, shows that independent and organisational employees are significantly less likely to support RLPs than interpersonal workers (decreases on the likelihood of voting for a RLP of 5 per cent and 2 per cent, p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively), but that there is no significant difference between interpersonal and technical employees. There is a small decline in the effect between independent and interpersonal employees after adjusting for positions on culture (Model Ib), and also when adjusting for positions on economic re-distribution (Model Ic). There are no significant changes to organisational employees in Models 1b and 1c.

Table 3. Average marginal effects of work logic and skill on support for the radical left in Southern Europe (2008–2020).

Turning now to the vertical distinction based on logics of authority, Model II establishes skilled routine workers as a reference category to estimate whether unskilled routine workers and associate professionals are more likely to vote for the radical left than this category. Considering that skill- and authority-based distinctions are less clear in the case of the self-employed, these individuals have been removed from Model II. Model IIa, adjusting for sociodemographic features, union membership, work in the public sector and religiosity, shows that being an associate professional or an unskilled routine worker increases the likelihood of supporting a RLP by 2 per cent (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively), compared to skilled routine workers. Professionals are also 3 per cent more likely to support the radical left, but this is only significant at p < 0.1. As expected in H2B, the likelihood of supporting a RLP decreases among professionals and associate professionals after adjusting for positions on cultural issues in Model IIb. In contrast, but also in line with the expectations of H2C, the difference between skilled and unskilled routine workers is not affected by cultural attitudes, but the coefficient decreases slightly (from 2 per cent to 1 per cent) after adjusting for positions on the economic dimension (Model IIb). Similarly, the likelihood of voting for the radical left also decreases slightly in levels of significance among associate professionals, thus suggesting that part of their support is mediated also by economic attitudes. The reverse happens, however, with professionals, which become strongly more likely to support the radical left than skilled workers after adjusting for positions on the economy (an increase of 4 per cent, p < 0.05).

Model III introduces both variables on work logic and skill levels in the same model. After including the two variables (Model IIIa), the previously noted differences remain statistically significant, with only a small decrease in the size of effect among unskilled workers (from 2 per cent to 1 per cent). This supports the argument that both dimensions matter in explaining class voting. Model IIIb introduces the variable for positions on cultural issues and shows that the effect of organisational work logic increases compared to Model Ib. This suggests that individuals in this work logic do tend to portray more socially liberal views, partially explained by its different skill-based composition, with lower numbers of unskilled occupations. In contrast, the effect of being a technical employee is more in line with the expectations of a cultural division based on work logic – the difference between technical and interpersonal employees, controlling for vertical class divides, decreases after introducing the variable for positions on cultural issues (Model IIIb) and increases after adjusting for positions on the economy (an increase of 1 per cent, but only significant at p < 0.1).

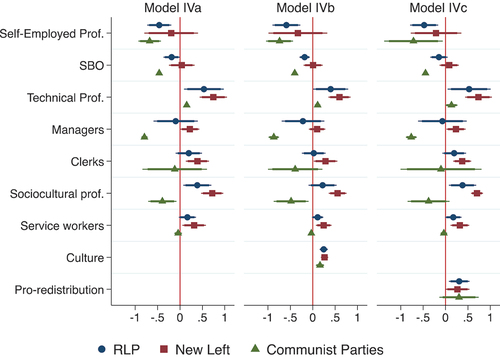

The average marginal effects of occupational class are presented in , which uses the occupational classes, explained previously that combine work logic and levels of authority and skill. The four-category skill dimension was merged into two categories – higher-grade (professionals and associate professionals) and lower-grade (skilled and unskilled routine) positions – to create Oesch’s 8-class schema (Citation2006). Considering the objective of understanding whether sociocultural professionals and service workers are more likely to support RLPs than production workers, the latter are used as a reference category. RLPs appear to attract significantly more support from technical specialists, sociocultural professionals (average marginal effects of 6 per cent and 4 per cent, p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively) and, to a lesser extent, service workers (2 per cent, p < 0.1) than production workers (Model IVa). Radical left support appears to be well distributed among other classes, apart from those independent professionals and small business owners, who vote significantly less for RLPs. The effect of being a sociocultural professional or a technical specialist is no longer statistically significant after adjusting for positions on the cultural dimension (Model IVb) but does not change after adjusting for positions on the economy (Model IVc). This furthers the argument that the higher-grade occupations, particularly sociocultural and technical specialists, are significantly more likely to support a RLP than production workers, and that this effect is in part mediated by cultural attitudes. This mediation is particularly relevant for sociocultural professionals.

Figure 2. Average marginal effects of occupational class on support for radical left parties in Southern Europe (2008–2020).

also explores patterns of occupational class voting for different subgroups within the radical left (full estimations available in Table A9). First, service workers are significantly more likely than production workers to vote for a new left party (2 per cent, p < 0.05). Sociocultural and technical professionals are also more likely than production workers to vote for these parties. In contrast, support for communist RLPs appears to be smaller among the self-employed and the higher-grade positions (managers and sociocultural professionals), except for technical specialists. Apart from this, their electoral base appears to be equally distributed among the other classes (production and service workers and clerks). Further lack of significant effects for this subgroup might however be related to lower sample size (1,389 respondents claimed to have voted for a communist party compared to 3,240 claiming to have voted for a new left party), but also to the fact that the electorate of PCP and KKE is more diverse than assumed (see Table A8 of the Online Supplementary material). Second, the argument that the impact of work logic is mediated by cultural attitudes is more noticeable also when new left parties are analysed separately. After adjusting for positions on cultural issues, sociocultural professionals and service workers are not significantly more likely than production workers to vote for new left parties (Model IVb), but both service workers and sociocultural professionals are more likely than production workers to support these parties. This difference is significant after adjusting for positions on the economy (Model IVc).

Discussion

Is there, then, a post-industrial pattern of class support for the radical left? This study has laid out three sets of hypotheses in this regard. The first was that individuals employed in an interpersonal work logic would be more likely than those in other work logics to vote for the radical left (H1A) because of cultural attitudes (H1B), and the results find partial support for this hypothesis. While interpersonal employees are indeed strongly more likely than the self-employed and organisational employees to support the radical left, the mediating effect of cultural attitudes is not present in most models, particularly when compared to organisational employees. Furthermore, while technical employees appear to be less likely than interpersonal employees to vote for the radical left, the differences are not always statistically significant. This can however be partially explained by internal differences within RLPs, as the mechanism of an interpersonal work logic driving RLP vote through a culturally progressive attitude is significant and follows the expected trends when new left parties are analysed separately ( and Table A9). These differences in effects can be interpreted as a combination of the ideological differences between a more socially liberal new left and more orthodox communist parties, but can also be traced back to historical legacies, different strategies of grass-roots mobilisation and the electoral specialisation these parties undergo when competing at the national level, as is the case in Greece and Portugal (Table A8 and A10).

The second set of hypotheses for a post-industrial alignment is that there is a vertical, skill-based distinction driving support for the radical left (H2A), which leads associate professionals to support the radical left because of cultural and economic preferences (H2B), and unskilled routine workers to support the radical left because of economic preferences (H2C). Support for this hypothesis is more unambiguous. In fact, both professionals and associate professionals are significantly more likely than skilled workers to vote for the radical left, and this effect loses part of its statistical significance after adjusting for positions on cultural issues, thus lending further evidence to the argument that cultural attitudes mediate support for RLPs among this group. The effect of being an associate professional also decreases after adjusting for positions on the economy, suggesting that associate professionals also vote for the radical left due to economic concerns. Similarly, unskilled workers are also significantly more likely to support the radical left than skilled workers and this effect appears to be moderated by economic attitudes. Importantly, both effects – among professionals and unskilled routine workers – decrease slightly but remain significant after adjusting for work logic.

Lastly, H3 posited that sociocultural professionals and service workers would be more likely than production workers to support the radical left. Sociocultural professionals are indeed significantly more likely to support the radical left in the evidence here presented, but so are technical professionals. Service workers do also appear to be more likely to support RLPs than production workers, particularly in the case of new left parties. At the party level, sociocultural and technical professionals are significantly more likely than production workers to support Podemos, SYRIZA and BE, while service workers are only more likely than production workers to support SYRIZA (Table A8, Online Supplementary Material).

This speaks to a broader process of post-industrial alignment in Southern Europe, with important implications for left-wing politics in this region. There is, on the one hand, the distinctive factor that the typical ‘Green electorate’ found in most Western European countries (e.g. Charalambous & Lamprianou Citation2017) is strongly more likely to support the radical left in Southern Europe. The effect of being a sociocultural or technical professional is, for instance, superior to that of working in the public sector, a variable often depicted as a central for RLP support. In the case of new left parties, the effect of being a sociocultural or technical professional even outweighs that of belonging to a trade union. On the other hand, RLPs’ clear position on the left on social and economic issues has allowed it to further its links with important segments of unskilled routine workers, particularly those within the new working-class of service workers. Further evidence of this can be found in the fact that class appears to play a significant role in the electoral competition in Southern Europe (Tables A9 and A10, Online Supplementary Material), with RLPs attracting the occupational groups typical of post-industrial societies (sociocultural professionals and service workers), and social democratic parties more likely to attract production workers.

Conclusion

The move towards post-industrial societies has changed the way class affects political preferences in European societies. Focusing on Southern Europe, where the rise of new radical left contenders since the Eurozone crisis has dramatically altered the composition of party systems in Greece, Spain and Portugal, this article sought to explain to what extent class shapes support for the radical left in the post-industrial era by drawing on data from the ESS and ELNES datasets from 2008 to 2020.

This analysis suggests that class continues to shape support for RLPs based on a post-industrial pattern. First, there is an underlying horizontal division in labour markets, based on work logic, which shapes support for this party family. More specifically, interpersonal employees, those for whom daily contacts with other people are the key factor in their daily work experience – usually in a face-to-face service logic – are significantly more likely to support RLPs than those in other work logics. An important part of this can be explained by interpersonal work driving a culturally progressive attitude, which in turn fuels radical left support – particularly for the more socially liberal new left parties (BE, SYRIZA or Podemos). This lends further evidence to the argument that, in post-industrial societies, the type of work and the experiences attached to it can influence voting behaviour as much as class position itself.

Second, this research also confirms that there is a vertical distinction within the labour market, based on levels of skill and logics of authority, which explains support for the radical left. Here, RLPs attract a significant number of middle-class professionals, most notably sociocultural and technical professionals, particularly influenced by their socially liberal attitudes. Southern European RLPs have been at the forefront of advancing a post-materialist agenda in Southern Europe, and this appears to have solidified the presence of progressive segments of the middle classes within the RLP electorate in this region. At the same time, while support for RLPs among the traditional working class of production workers is remarkably low, these parties have nonetheless been able to attract a significantly higher number of workers of the ‘new working-class’, the precarious workers in the expanding service sector. This is important for RLPs’ electoral prospects, given that these occupations encompass a large and growing number of the working population in post-industrial societies.

These results speak thus to RLPs’ capacity to build a social coalition to expand their electoral support. This social coalition involves a core electorate of middle-class professionals with progressive views, as well as segments of the new working class of service workers. Beyond them, RLPs do often attract some support from other occupational groups, such as clerks, but fail to make significant inroads into the more traditional working-class. It is however unclear how stable such a social coalition is. Southern European RLPs have likely benefitted from the historical absence of strong Green parties, which tend to attract the same electorate who disproportionately voted for RLPs in this study (technical and sociocultural professionals). Similarly, the rise of radical right parties in many Western European countries has been tied to a capacity to attract significant parts of both new and old working-class electorates. Future research should thus seek to broaden the empirical scope of this article, for example by including more recent developments in countries such as Portugal and Spain, where the electoral stagnation of RLPs alongside the rise of the radical right has arguably provided a fertile ground for further studying of the dynamics of class presented here.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (516.1 KB)Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Jose Rama, Robert Ford and Maria Sobolewska for their insightful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplementary data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2024.2359825

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

José Pedro Lopes

José Pedro Lopes is a PhD candidate at the University of Manchester. His research focuses on political parties and voting behaviour, with a special focus on radical left parties and Southern European countries.

Notes

1 The term ‘new middle-class’ refers mostly to sociocultural specialists, occupations associated with the increasing demand for ‘quality of life’ in post-industrial societies (e.g. health, education, arts). In contrast to the ‘old middle-class’ of technocrats and managers, this is primarily a professional class based on knowledge rather than property (Bell Citation1973).

2 The agreement between the Spanish socialists and the parties to its left was re-enacted after the 2023 general election. In this election, Podemos ran as part of the Sumar coalition, but left the coalition in December 2023.

3 Data from the September 2015 ELNES survey was not included, given that this survey does not have a variable distinguishing between self-employed (or employer) and employed workers, which prevents the construction of the 8-class schema.

References

- Antunes, R. (2018) ‘The new service proletariat’, Monthly Review, vol. 69, no. 11, pp. 23–29.

- Ares, M. (2020) ‘Changing class, changing preferences: how social class mobility affects economic preferences’, West European Politics, vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 1211–1237.

- Bartolini, S. (2000) The Political Mobilization of the European Left, 1860-1980, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Bell, D. (1973) The Coming of Post-Industrial Society. A Venture in Social Forecasting, Basic Books, New York.

- Beramendi, P., Häusermann, S., Kitschelt, H. & Kriesi, H. (2015) The Politics of Advanced Capitalism, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Bornschier, S. & Kriesi, H. (2014) ‘The populist right, the working class, and the changing face of class politics’, in Class Politics and the Radical Right, ed J. Rydgren, Routledge, London, pp. 10–30.

- Bulfone, F. & Tassinari, A. (2021) ‘Under pressure. Economic constraints, electoral politics and labour market reforms in Southern Europe in the decade of the great recession’, European Journal of Political Research, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 509–538.

- Charalambous, G. (2022) The European Radical Left – Movements and Parties Since the 1960s, Pluto Press, London.

- Charalambous, G. & Lamprianou, I. (2017) ‘The (non) particularities of West European radical left party supporters: comparing left party families’, European Political Science Review, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 375–400.

- Chiochetti, P. (2017) The Radical Left Party Family in Western Europe, 1989–2015, Routledge, New York.

- della Porta, D. (2012) ‘Mobilizing against the crisis, mobilizing for “another democracy”: comparing two global waves of protest’, Interface, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 274–277.

- ELNES. (2012) Hellenic Voter Study 2012, Hellenic National Election Studies, Greece.

- ELNES. (2015) Hellenic Voter Study 2015a, Hellenic National Election Studies, Greece.

- ESS, (2022) European Social Survey Cumulative File 1-10: Data File Edition 1.0, Sikt - Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, Norway.

- Fagerholm, A. (2017) ‘What is left for the radical left? A comparative examination of the policies of radical left parties in western Europe before and after 1989’, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 16–40.

- Gomez, R., Morales, L. & Ramiro, L. (2016) ‘Varieties of radicalism: examining the diversity of radical left parties and voters in Western Europe’, West European Politics, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 351–379.

- Gomez, R. & Ramiro, L. (2022) Radical Left Voters in Western Europe, Routledge, London.

- Keith, D. & Charalambous, G. (2016) ‘On the (non) distinctiveness of Marxism-Leninism: the Portuguese and Greek communist parties compared’, Communist and Post-Communist Studies, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 147–161.

- Kitschelt, H. & Rehm, P. (2014) ‘Occupation as a site of political preference formation’, Comparative Political Studies, vol. 47, no. 12, pp. 1670–1706.

- Kitschelt, H. & Rehm, P. (2022) ‘Polarity reversal: the socioeconomic reconfiguration of partisan support in knowledge societies’, Politics & Society, vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 520–566.

- Kohn, M. & Schooler, C. (1982) ‘Job conditions and personality: a longitudinal assessment of their reciprocal effects’, American Journal of Sociology, vol. 87, no. 6, pp. 1257–1286.

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, R., Bornschier, S. & Frey, S. (2008) West European Politics in the Age of Globalization, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Lisi, M. (ed) (2019) Party System Change, the European Crisis and the State of Democracy, Routledge, London.

- Lourenço, P. (2022) ‘Programmatic change in Southern European radical left parties: the impact of a decade of crisis’, Mediterranean Politics, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 186–209.

- March, L. (2011) Radical Left Parties in Europe, Routledge, London.

- March, L. & Keith, D. (eds) (2016) Europe’s Radical Left: From Marginality to the Mainstream?, Rowman & Littlefield International, New York.

- March, L. & Mudde, C. (2005) ‘What’s left of the radical left? The European radical left after 1989: decline and mutation’, Comparative European Politics, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 23–49.

- McLaren, L. M. (2008) Constructing Democracy in Southern Europe, Routledge, London.

- Moreira, A., Domínguez, A. A., Antunes, C., Karamessini, M., Raitano, M. & Glatzer, M. (2015) ‘Austerity-driven labour market reforms in Southern Europe: eroding the security of labour market insiders’, European Journal of Social Security, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 202–225.

- Narotzsky, S. (2020) Grassroots Economies: Living with Austerity in Southern Europe, Pluto Press, London.

- Oesch, D. (2006) ‘Coming to grips with a changing class structure: an analysis of employment stratification in Britain, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland’, International Sociology, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 263–288.

- Oesch, D. (2015) ‘Occupational structure and labour market change in Western Europe since 1990’, in The Politics of Advanced Capitalism, eds P. Beramendi, S. Häusermann, H. Kitschelt & H. Kriesi, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 112–132.

- Oesch, D. & Rennwald, L. (2018) ‘Electoral competition in Europe’s new tripolar political space: class voting for the left, centre-right and radical right’, European Journal of Political Research, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 783–807.

- Ramiro, L. (2016) ‘Support for radical left parties in Western Europe: social background, ideology and political orientations’, European Political Science Review, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–23.

- Rooduijn, M., Burgoon, B., van Elsas, E. J. & van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2017) ‘Radical distinction: support for radical left and radical right parties in Europe’, European Union Politics, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 536–559.

- Sánchez-Mosquera, M. (2023) ‘The influence of the political attitudes of workers and the effect of the great recession on the decision to join a trade union in Southern Europe’, Economic and Industrial Democracy, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 579–599.

- Stegmueller, G. (2013) ‘How many countries for multilevel modeling? A comparison of frequentist and bayesian approaches’, American Journal of Political Science, vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 748–761.

- Thomassen, J. (2005) The European Voter: A Comparative Study of Modern Democracies, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Tsakatika, M. & Lisi, M. (2013) ‘“Zippin’ up my boots, goin’ back to my roots”: radical left parties in Southern Europe’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 1–19.

- Visser, M., Lubbers, M., Kraaykamp, G. & Jaspers, M. (2014) ‘Support for radical left ideologies in Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 541–558.