Introduction

Mentoring is a key component in developing new and early career faculty for success. In the past, mentoring in higher education institutions has focused on the one-on-one relationship between a more experienced, tenured faculty member and a junior faculty member. Scholars in the mentoring field have given attention to broader models that engage multiple mentoring partners in non-hierarchical, collaborative (Jipson & Paley, Citation2010; Mullen, Citation2000; Yun, Baldi, & Sorcinelli, Citation2016) and cross-cultural partnerships (Guramatunhu-Mudiwa & Angel, Citation2017; Johnson-Bailey & Cervero, Citation2002). Particularly for underrepresented populations and women in institutions of higher education (IHEs), mentoring models that are more inclusive, strategic, and relational have been found to be more successful in assisting early career faculty meet their professional goals (McGuire & Reger, Citation2003; Mullen, Citation2005; Wasburn, Citation2007; Yun et al., Citation2016).

Mentoring relationships are an important aspect of career development in many professional fields including education (Ehrich, Hansford, & Tennent, Citation2004), law (Haynes & Petrosko, Citation2009; Wallace, Citation2001), medicine (Kashiwagi, Varkey, & Cook, Citation2013) and business (Anafarta & Apaydin, Citation2016; Hansford, Tennent, & Ehrich, Citation2002). Such relationships serve as a means to increase retention and job satisfaction (O’Meara, Citation2015). Within IHEs, new faculty are often faced with the pressures of engaging in quality teaching, being collegial, increasing scholarly activities, and incorporating the uncertainties of institutional expectations and resources. More specifically, new faculty members are often overwhelmed with the demands to publish as they balance their teaching and service work loads (Bin Tareef, Citation2013; Jacobs & Winslow, Citation2004; Valian, Citation1999; Wilson, Citation2001). As Whitt (Citation1991) pointed out, ‘A common complaint among new faculty is that they are expected to “hit the ground running” but are not given specific assistance, resources, or direction to help them get off to a good start’ (p. 179). Badali (Citation2004) found untenured professors of education face greater tension than tenured faculty in areas of workload and time, especially when trying to balance teaching and scholarly work. Although the untenured faculty members typically begin with high ideals for themselves, they are often overwhelmed with the increasing pressures and stressors mentioned previously whether in the classroom, in their buildings, and/or in their own offices. This occurs after finding that the institution’s specific expectations for tenure are not clearly defined, and support from higher administration is lacking (Rice, Sorcinelli, & Austin, Citation2000).

When IHEs recruit, select, and hire new faculty members, the institutions are making major investments of resources and trust. They expect new faculty members to thrive at the institution, find intellectual excitement and professional satisfaction, and contribute their talents to further achieve institutional missions. Boyle and Boice (Citation1998) considered the academe’s historically ‘laissez-faire approach to mentoring’ to be an obsolete and unrealistic approach to supporting a diverse cadre of faculty members, because ‘the newcomers least likely to find spontaneous support like mentoring are women and minorities’ (p. 159). However, other scholars hold the perspective that mentoring should develop under naturally occurring relationships (Fries‐Britt & Snider, Citation2015; Suriel, Martinez, & Evans-Winters, Citation2018) where transparency and vulnerability serve as a catalyst for more authentic mentoring experiences. Furthermore, when IHEs do offer mentoring, it is often conceptualized as a transactional, hierarchical, instrumental model, as opposed to a developmental, reciprocal model or framework. Mentoring relationships are crucial for new faculty as they learn unfamiliar tasks, develop research agendas, find support for teaching and research, balance work and home life, network with others at professional development opportunities, and understand the political issues and expectations associated within their institutions (Johnson, Hastings, Purser, & Whitson, Citation2011; Mullen & Forbes, Citation2000; Yun et al., Citation2016).

Socialization and identity development among early career faculty are integral in the mentoring process. Socialization processes facilitate individuals in becoming part of an institution as they adopt norms, expectations and standards (Cawyer, Simonds, & Davis, Citation2002; Yun et al., Citation2016). Albrecht and Bach (Citation1997) explained, ‘during the socialization process an individual comes to appreciate the values, expected behaviors, and social knowledge essential for assuming a role in the organization and for participating as an organizational member’ (pp.196–197). Learning, socialization and identity development then becomes an ‘evolving form of membership’ (Lave & Wengler, Citation1991, p. 51). However, not only is socialization a process where new faculty learn their roles in the institution, but one that is also bidirectional as institutions learn to adapt to their new members (Tierney & Rhoads, Citation1994). In this reciprocal process, there is interplay between the organizational culture and the individual. Hence, rather than replicate the organizational culture, the newcomers ‘re-create’ it as they bring their own expectations and ideas to the organization (Tierney, Citation1997).

In this paper, we illuminate how a developmental mentoring framework can be utilized for mentoring a junior faculty member, a tenured faculty member, and the department head, who also served as a mentor to both faculty members. In the process, we provide insights on what we learned through this experience, as we engaged in a mentoring relationship within a complex system of the university where the department head served as a mentor and a supervisor to the two faculty members. In this paper, we specifically address the following questions:

What are the experiences of a new pre-tenured faculty mentee, faculty mentor, and department head when they mutually engage in a developmental mentoring process?

How do the mentoring narratives inform the ongoing process of identity development?

A developmental network perspective to mentoring

Although there is no universal definition for mentoring, numerous researchers have agreed upon various functions necessary to uphold the mentoring role. Mentoring is often conceptualized as a positive learning experience by both the mentor and mentee and is dependent upon several factors including the stage of career development, the organization, the setting, and the type of profession (Higgins & Kram, Citation2001; Kram, Citation1988; Rankin, Citation1991). Mentors may offer advice, provide information, interpret cultural practices, traditions, and codes, act as role models, advisers, guides or advocates in a variety of formal and informal settings (Anafarta, 2015; Bin Tareef, Citation2013; Jipson & Munro, Citation1997; Jipson & Paley, Citation2010; Johnson, Citation2007; Kapustin & Murphy, Citation2008; Trower, Citation2012). In our experience we acknowledged our mentoring relationship as a developmental network (Higgins & Kram, Citation2001; Kram, Citation1988) that created opportunities to mutually discuss interests, needs, and issues related to our personal lives as well as our teaching, scholarly work, and outreach obligations.

Increasing attention has been given to developmental networks as an alternative to traditional forms of mentoring (Haggard, Dougherty, Turban, & Wilbanks, Citation2011). In utilizing an inter-relational developmental network, we were intentional about engaging with this process in a non-traditional manner. The hierarchical nature of traditional mentoring models, offer some limitations for women and faculty from underrepresented populations. In higher education, men typically have more senior positions and are promoted to leadership positions faster than women. Additionally, traditional mentoring sometimes reifies the masculine notions of power that limits definitions of scholarship and intellectual contributions of women, (Gibson, Citation2006; Katuna, Citation2014; Wasburn, Citation2007) subsequently limiting authentic mentoring experiences.

Higgins and Kram (Citation2001) defined an individual’s developmental network as a set of people who play a variety of supportive roles in the career advancement of the mentee. There are four central concepts in a developmental relationship network as prescribed by Higgins and Kram (Citation2001): (a) the developmental network itself, (b) the developmental relationships, (c) the diversity of the developmental network, and (d) the strength of the developmental relationships that make up the developmental network. Developmental relationships may include those who provide career support and psycho- social support (Thomas & Kram, Citation1988).

Developmental network diversity involves the extent to which the flow of information is varied and different. Higgins and Kram (Citation2001) referred to network diversity as a source of varied information provided from different social systems. For instance, the department head is a different source of information than the faculty mentor. Higgins and Kram clarified, that in this case ‘This diversity concerns the nature of the relationships held, rather than the attributes of the developers’ (Citation2001, p. 269). Hence, the diversity in this network lies in the kind of information provided by the department head and the faculty mentor.

Developmental networks can also aid mentees in developing their professional identities. DoBrow and Higgins (Citation2005) noted, ‘the extent of clarity regarding one’s professional identity will be related to the variety of support one receives from developmental others’ (p. 570). In this case, the department head and the tenured faculty member provided the variety of support. Professional identity is defined as ‘the relatively stable and enduring constellation of attributes, beliefs, values, motives, and experiences in terms of which people define themselves in a professional role’ (Ibarra, Citation1999, pp. 764–765). In institutions of higher education, professional identity development becomes a crucial component of how early career faculty members define themselves in their respective contexts.

Drawing from the above perspectives (Higgins & Kram, Citation2001; Kram, Citation1988; Rankin, Citation1991) on developmental network mentoring, we utilized a model that integrated the inter-relationships among the new faculty, the tenured faculty and the department head. In order to contextualize the mentoring process, below we offer some background on how the relationships among the authors emerged including the institutional setting.

Context

At the time of this research, we worked at a land-grant university in a rural, predominantly White, Mid-west institution whose mission focuses on teaching, research, and outreach. According to the university’s Human Resources Office, 16.7 % of the faculty were minorities with Black/African American faculty consisting of 1 %, and the predominant minority population (10%) being Asian. The Dean at the College of Education and Human Sciences initiated a faculty mentoring plan which entailed individualized mentoring – a formal mentoring relationship that needed to be established within two months of employment. The mentor’s assignments as defined by the Dean’s office included, offering advice to the mentee on all aspects of her assignments, sharing expertise and experience in classroom teaching, starting and sustaining a scholarship and outreach programs. The mentor was to meet with the mentee monthly for lunch and visit about her progress. The Dean’s office offered a small monetary allocation for the one-on-one meetings. The mentor would be able to count the mentoring opportunity towards her professional activities in the annual report. The mentee was to actively seek advise from the mentor including sharing any updates or progress in the areas of teaching, research and service. It was within this context that the junior faculty member met with the tenured faculty. It is important to note that although this was the mentoring plan prescribed by the Dean’s office, the junior faculty, tenured faculty and department head chose to re-envision the mentoring plan as an inter-relational model among the three of them. We offer a brief account of how the relationships emerged.

Christine

As a new pre-tenure faculty, I (Christine) knew that I needed a mentor to help me navigate the transition from being a doctoral student to the professoriate. I wanted to understand the organizational culture of the department and successfully accomplish my teaching, research and service duties. As a doctoral student, I had witnessed the rigor and commitment it took for faculty to make tenure. Upon being hired, my department head asked me if I had someone in mind whom I wanted to mentor me within the College of Education and Human Sciences. Although I had already become acquainted with some of the faculty in the department and the college, I did not know them well enough to choose my own mentor. I was delighted when the department head assigned Mary to be my mentor. While at the beginning of the mentoring relationship I did not know my mentor well, I was aware of her work ethic, her approachable personality, and the fact that she had successfully attained tenure. I therefore looked forward to developing a relationship with her and learning from her experience.

Mary

When I (Mary) was hired, I was not assigned to a formal mentor other than my department head. He offered great insights and information related to the questions I had. However, being in an administrative role, certain questions arose that I felt needed a faculty member’s perspective. When Christine was hired, I wanted to ensure she had the resources and support she needed to progress in her promotion and tenure attainment. At the time, the goal of the newly developed College of Education and Human Sciences mentoring plan was to assign a senior faculty mentor having similar interests and workload assignment to each new pre-tenure faculty member. This initiative from the Dean’s office was created to ensure the mentee would receive support in order to achieve excellence in all areas of responsibility, including teaching, advising, research, and service, and be fully prepared for the tenure and promotion process. The specific responsibilities of a mentor included offering assistance and support to the mentee on all aspects of a pre-tenure faculty member’s assignments. Such assistance involved sharing expertise and experience in classroom teaching; developing a research agenda; writing for publication; and determining an appropriate level of service. In this way, the mentor could assist the new faculty member become oriented to important campus resources and facilities; receive information on important dates, events, and meetings; and accompany her, as able, to meetings and events. The mentors received these guidelines from the Dean’s office before they assumed their roles.

Andrew

As a department head, I (Andrew) believed that being a faculty developer was one of the most important aspects of my role. For more than a decade, I have mentored pre-tenure faculty to be successful as teachers and researchers using a developmental networking process (Higgins & Kram, Citation2001; Walker, Citation2006). While traditional mentoring is often concerned primarily with the teaching of techniques, strategies, and technological tools (which can be learned via workshops and tutorials offered through the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning or Instructional Design Service), developmental mentoring, from my perspective, is about using conversation and questioning to foster and support the development of self-awareness, self-understanding, and personal wholeness. My intention is to enable new faculty to bring identity and integrity more fully into their professional lives, which, in turn, might foster morale, work satisfaction, and collegiality and cohesiveness within the department. It is my goal to shape professional identities, develop a relationship of trust and mutual respect for the talents and abilities faculty bring to their positions, while nurturing faculty in their development as skilled teachers and researchers.

Building on the notion that reflective dialogue is an essential process in supporting faculty to be successful in teaching, building community with colleagues, fostering purpose and meaning, and providing developmental mentoring, we utilized narrative inquiry as our primary methodology.

Methods and data sources

We explored our individual experiences as a pre-tenure faculty, a mentoring tenured faculty, and a department head, through a narrative inquiry space (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation2000). In this inquiry space, we attended to the temporality (the past, present and future), of our mentoring experiences, sociality (our relationships among us and our relationship to the institution) and place (the context in which we worked). Thinking through the three dimensions of narrative inquiry allowed us to conceptualize our understanding of mentoring as relational, temporal and contextual. Our data were drawn from personal mentoring narratives (which generated over 20 single spaced pages), university requirements, conversations among us, mentoring notes that we took during and after our monthly meetings, and numerous email threads.

Christine and Mary met regularly during Christine's first and second year as a new faculty member. We documented in our journals about our discussions before, during, and after the meetings. We also met regularly with Andrew, who believed that mentoring was an important part of his role as an academic leader. Some of the meetings were formal, with clear set goals, while others were informal. The content of the meetings involved dialogue about teaching; writing publications and proposals; providing feedback on new and upcoming projects; answering questions; and providing support, advice, and resources when requested. We then wrote our own personal mentoring narratives, which we shared with one another on a monthly basis. The mentoring narratives often entailed reflections of our dialogues, outcomes we were excited about regarding publications or teaching and also personal contemplations regarding our evolving relationships.

The inter-relational mentoring relationship became a narrative inquiry developmental space as we transformed coffee shops, our offices, building hallways, and even our shared narratives through emails into a portal that held our stories of experience. The process offered us reciprocal learning and mentoring opportunities for all three of us. We recognized the importance of situating our learning experiences with the temporal dynamics of the university institution such as the changing expectations and demands of university faculty and the impact of learning from one other (de Janasz & Sullivan, Citation2004). The context in which we worked, a rural predominantly White institution, was also in consideration.

After the end of the second year, we systematically and carefully analyzed the collected data from our dialogues, which consisted of communication with each other during meetings and personal mentoring narratives, and then coded them thematically. Connelly and Clandinin (Citation2000) noted that field texts can be interwoven from a variety of sources such as journal writing, personal accounts, letters, conversations, interviews, documents and photographs. Researchers can utilize varied sources of data to compose and retell a narrative in order to make meaning of an experience in a research text. Downey and Clandinin (Citation2010) cautioned narrative inquirers of the struggle to create smooth coherent texts as researchers move from field texts to research texts. Our storied and re-storied texts were sometimes shared in fragments and in a non-sequential manner. The narrative accounts that reflect the three themes below were derived after multiple ‘composing, co-composing and negotiation of interim and final research texts’ among the three of us (Clandinin, Citation2013, p. 49). This was a process that took numerous conversations and alliterations in order to recreate a research text.

Upon multiple readings and sharing of interim research texts, three themes were apparent: (a) reciprocity, trust and advocacy; (b) identity development through managing change processes; and (c) re-conceptualizing mentoring as a developmental inquiry space as evidenced by individual’s processes of growth. These themes were derived from scaffolding and analysis using the three commonplaces of narrative inquiry – place (context), temporality (time) and sociality (relationships) as outlined by Clandinin, Pushor and Orr (Citation2007). Utilizing these common places allowed us to understand our particular context in relation to the change processes that were happening at the university and in the department. Additionally, those change processes also shaped our professional growth as faculty. The narratives that emerged from the process became a means to understand the interconnections among knowledge, context, and identity (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation1999). As Polkinghorne (Citation1988) pointed out, human beings make meaning of experience through narratives. Hence, narratives become ‘the means by which we make sense of our past, our present and our future, even as the stories themselves gradually “fuse” with new stories as new experiences occur’ (McLean, Citation1999, p. 78).

Our aim was to use dialogue and personal narratives to reflect on and document current and past experiences, interactions with each other, initial thoughts and insights after meeting with one another, and to decipher themes that emerged from utilizing a developmental, non-hierarchical mentoring framework. The narratives below represent a restoried process of the themes that were evidenced in the personal narratives and conversations. These narratives depict the complex web of context, time, and the value of the relationships among us. The three dimensions of the inquiry and the themes are interconnected and interwoven with the intention to ‘engage the audiences to rethink and reimagine the ways in which they practice and the ways in which they relate to others’ in a mentoring context (Clandinin, 2013, p. 51).

Retelling our stories

Christine

I remember the day I interviewed for the faculty position. Though I did not know whether I had ‘made the cut’ I hoped for a positive outcome. I believed I had made a connection with the department head (Andrew) during the interview process. Although his specialization was Early Childhood and mine was Educational Leadership, we shared certain common interests in our orientation towards teaching and learning. At the time, the department was a large entity that served several undergraduate and graduate programs. At the undergraduate level, the department offered majors in early childhood education, family and consumer sciences education, and agricultural education. However, the latter two majors and 21 content majors also resided within four different colleges: Education and Human Sciences, Arts & Sciences, Engineering, and Agriculture and Biological Sciences. At the graduate level, the department housed programs in Curriculum and Instruction and Educational Administration. It is important to emphasize that this department was both complex and unique. For instance, the department did not have an elementary education program and it was housed in two separate buildings on campus. In sum, the unit was not well integrated or unified under a School of Education and faculty had to be intentional about building collegiality given the dynamics. As a new faculty member, I initially tried to understand all the intricacies of the department and the different programs, including how for instance students in secondary teacher education were also ‘shared’ with other colleges at the university. With my specialization in educational leadership, I wanted to understand how faculty members were integrated along with the other faculty from other specializations.

During my interview process as a job candidate, I discovered that one common research interest with Andrew, the department head was our love and respect for the work of Parker Palmer, especially his text, The courage to teach: The inner landscape of a teacher’s life (Palmer, Citation1997–2007), which informs my philosophy of teaching. When I mentioned Parker Palmer’s work in my interview presentation, I knew from his sense of affirmation that we would connect on some of our views on teaching and learning.

The first conversation we had on the day I interviewed remained vivid in my memory. Andrew mentioned that he wanted to hire faculty who could play a positive role in ‘changing the culture of the department.’ As someone who was not afraid of change or challenge, I contemplated on this assertion. However, looking back, I did not fully understand the weight and magnitude of those words. I had no idea the kind of struggles we would face concerning the change processes happening in the department and in the university. I slowly came to realize that the cultural change was going to be a test and a growth process to my personal and professional identity.

After a few months of settling in, the department head, (Andrew) informed me that Mary would be my faculty mentor. Though I did not know her well, I knew that she was personable, approachable, and had recently attained promotion and tenure successfully. Additionally, because she worked in the Early Childhood program, and I had students from her program in my courses, I wanted to learn more. She was always timely in scheduling our monthly meetings and would reach out to me, not only to know how I was doing personally and professionally. She would provide meaningful and useful feedback when I needed clarification, for instance after faculty meetings or when I experienced situations with students and was not sure on how to handle them.

Moving to the upper Midwest from the East Coast was a major transition for me. Although, I had planned for the change, the transition was challenging personally and professionally. Our department was involved in program redesign at the undergraduate and graduate levels. Discussions about the changes created a lot of fear and resistance from other faculty. Additionally, integrating my specialization of educational leadership into the department was sometimes a challenge. Author 3 and Author 2 constantly assured me that my expertise was valuable. Although my specialization was in educational leadership, I was assigned to teach English as A Second Language certification courses and a diversity course in teacher education. While I had a level of expertise in the content of these courses, I was uncertain as to whether my specialization fitted within the department. Looking back at my first year, there had been many positive changes through the program redesign process but also challenges. I therefore needed to rethink how I was going to situate myself in the department and generally in higher education.

Concerning my teaching, I felt that some students struggled with the content of my classes, which were based on educating for equity and justice. Difficult dialogues such as those on race can feel threatening between members of different ethnic and racial groups (Sue, Lin, Torino, Capodilupo, & Rivera, Citation2009). Some students constantly tried to undermine my teaching by sometimes suggesting that the facts I offered in classroom were not true. Some also felt that there was no need to address issues of equity and inclusion in the classroom because the rural Midwest is not very diverse. Such words were disturbing to hear, especially because the communities that the teacher education students served were changing demographically and some schools were situated in socio-economically disadvantaged communities. As I read the journal entries I had written then, three years later, I realized how time had influenced my interpretation of such experiences. I had learned how to better deal with such challenges through persistence and by understanding the realities of my students and where they were coming from. I wanted to understand their histories and backgrounds better so that their stories would be part of my teaching. The changes taking place in the university and the community also positively impacted students’ understanding of the need to build a knowledge base about human diversity, justice advocacy for the underserved in schools. Additionally, I learned that relationships take time to build and developing mutual trust is critical. Although some dialogues were difficult in the classroom, there were still positive outcomes. In one instance, a student asked at the end of the semester, ‘So where do we go from here? We want to learn more.’ It was encouraging to see the shift in students’ perceptions and attitudes.

Part of my growth process was in understanding the larger context and envisioning what ‘starting below ground zero’ meant for my students and I. My mentor and department head regularly affirmed and helped me reflect through our conversations and journal entries on the value of my work in such a context. Looking back, I realized that it takes time for people to understand a ‘new language’ in a certain discipline. When the language is unfamiliar, people may feel threatened. Scholars researching on the experiences of Black faculty have documented how students often question their credibility and intellectual authority in the university classroom (Harlow, Citation2003; Johnson-Bailey & Cervero, Citation2008). Such experiences can negatively impact a professor’s conception of self, especially if their identity is in part shaped by the interactions of with others and in this regard, the classroom. It takes time for students to develop a certain comfort level in developing relationships and discussing controversial topics such as race and poverty when they have had little exposure to such dialogue in a classroom setting. I learned to be patient and not to define my sense of self by what students thought about me, or the content that I taught. Developing a professional identity for me also meant helping my students understand the larger diverse world that we live in and what it takes to become a teacher or principal who is equity and justice minded. I therefore felt that I had a duty to offer my students a space where dispositional shifts could take place in order for them to accommodate not only their own lived realities but also the realities of others who are different from them.

Mary

Upon returning in the fall of 2013, I was asked by Andrew to mentor a new junior-faculty member within our department. He stated that because I had taught at the university for several years and recently attained tenure and promotion, I would know the expectations and could identify how a mentee may feel while pursuing these goals. I did not know Christine very well and was apprehensive about what I could offer, particularly because I had never defined myself as a mentor. I tried to view this as a new opportunity for Christine and myself. I, like my department head, wanted this newly hired faculty member to thrive and be successful in her academic career.

I questioned and wondered whether the university administration wanted an informal networking, interpersonal model of mentoring to unfold or a transactional, hierarchical and formal relationship that centered primarily on providing scholarly assistance. I identified myself as a relational, interpersonal person; I want others to know I care for them, and will accept them for who they are, not what others want them to be. I also advocate for mutuality and enhancement. Therefore, in my own mind, my primary goal was to be proactive, showing deliberate and generative concern, encouragement, support, and guidance, while recognizing our unique relationship as being trusting, rather than hierarchical. I wanted to see mentoring from a developmental network perspective, where we both grew professionally and personally.

During our monthly meetings, Christine expressed concerns and asked questions about various aspects of the academic and institutional culture. As an international, Black faculty in a rural, predominantly White area, she felt somewhat excluded and disregarded in meetings and informal conversations when certain issues arose in which she had expertise. For example, when colleagues asked about transforming the Educational Administrative Graduate Program, although Christine had recently been to several Educational Administrative national conferences and knew of various vibrant and viable programs, her ideas were dismissed. She was not an individual who blamed others but rather asked about her expectations. I wondered what I could do to help her. I did not want her to falter due to others’ negative, and possibly inappropriate, views and actions, so I pondered this question and decided to take matters into my own hands. I began to question others in an open, non-directive manner. What did they see in this person? What could she offer that others may not?

I wanted her to know her ideas, views, and experiences were worthy. Being proactive in my approach, helping her feel a sense of accomplishment, and helping others see her value in the department guided my discussions and questions. What I found was that she was doing the same for me, she was providing me with advice and resources, reciprocal components to the mentoring process. She also acknowledged my accomplishments, asked me about my life, both professionally and personally, and provided advice and resources when requested. She was becoming more confident in herself and her abilities, and, likewise, I was becoming more confident in my abilities and self-worth.

Author 1 also was beginning to form her own sense of self at this institution, sharing with students her various experiences and her strong knowledge and research base. Seeing an upsurge in her teaching and scholarly work instilled in me a sense of delight and pride, as a parent may feel when a child accomplishes something he/she has tried so hard to overcome. She was showing others who she was – a strong, positive, caring, and successful educator and scholar.

Throughout this time and for many years prior to this, Andrew also was mentoring me. Although I had recently obtained tenure and promotion, he still met with me on a bi-monthly basis to provide support and make sure my teaching, research and service agendas were moving forward. These regular meetings consisted of questions about how I was doing both professionally and personally, along with resources or ideas he might provide to help me for attaining my professional goals. I struggled with my workload assignment and my role as a parent. With four children under the age of 14 at home and a husband who farms and is unavailable during a large portion of the year, I needed my mentor’s support and advice.

As I worked towards the attainment of full professor status, I continually thought about the challenges and time commitment it would take to get there and I some times struggled. He shared new ideas related to my work-family balance, about our program area, and he encouraged me to think carefully about my challenges in terms of my values and beliefs. He listened to my ideas and assessed my strengths and determined how those strengths could be used to build and leverage the department and program area, especially when change was apparent. Although I believe my identity was not transformed in significant ways, his advice and support created feelings of safety and security, a place where I could ask questions freely. I eventually made full professor! The meetings with Andrew included turn taking, co-leading, dialoguing, and providing constructive feedback and authenticity in learning about myself, components I saw within my meetings with Christine, as well.

Andrew

As has been stated above, I have served as a mentor for both Christine and Mary. I mentored Mary through her tenure and promotion to associate professor. These mentoring opportunities included regular meetings where we discussed her questions related to teaching and research and strategies for negotiating the tenure process. I have also served as a collaborator in research, where my role was to encourage but not direct, guide but not get in the way. Typically, I helped her and others to think through their methodologies, revisit their questions, and support them in their writing. Most importantly, I have tried to help her identify and utilize her strengths, and provide safe boundaries within which she could decide what was helpful, and where she could ask questions without fear, take risks without rejection, and make mistakes without penalty. The hospitable mentor must reveal to the mentee that she has something to offer. I wanted her to understand that in her research and in her journey, her own life experiences, insights and beliefs, and theories and assumptions were worth serious attention.

During her first two years, I mentored Christine, visiting with her on occasion to talk about her teaching and research and to listen to her concerns, work through her feelings about the relationship dynamics among faculty, and to pay close attention to her ideas for moving us forward as a department in transition. In many ways, our meetings have provided a space where we can become present to each other, reveal our perspectives and visions for the department, and support each other in our common struggles with the process of leading change.

Like teaching, mentoring is about enabling mentees to make good choices, it is about supporting their development, and it’s about hospitality, reaching out and inviting them to a new relationship. It is leading in the process of becoming, in which each mentee is viewed as a developing human being with specific needs and demands, hopes and desires, passions and interests, potentials and rights. It is an awesome task and an awe-inspiring ethical challenge.

Three main ideas have guided my mentoring: a) that it is possible as a department head to both supervise (and, therefore, evaluate) faculty and be a mentor to them; b) that mentoring, like teaching, is a pedagogical orientation toward the person being mentored; and c) that mentoring requires an attitude of hospitality. My mentoring of both Christine and Mary have helped shape me as a person and as an academic leader.

It is possible to supervise and evaluate faculty and mentor them, of that I am certain. In fact, I believe that mentoring has made me a better supervisor. Developing faculty is one of the major responsibilities of a department head or chair. Through mentoring, I tried to ‘be present’ with precise and focused attention to Christine and Mary, and to listen astutely to their voiced concerns, questions, and needs. This was not easy. I often tried to give advice or solve a problem without really listening. It was Author 1 who once told me that what she really needed was for me to listen and not necessarily try to fix or resolve things. This is a simple, yet powerful message. As a department head, I needed to make decisions quickly and often. Sometimes I did not listen carefully enough before acting. But, as a mentor, this was crucial. Without presence, mutual trust and understanding cannot develop and hospitality cannot be extended. Hospitality defines a space for faculty members to be themselves, because they are received graciously and sincerely, and the singularity of each person and the diversity of their needs can be considered. Developing this orientation towards Christine and Mary helped me view evaluation more appropriately as a developmental task, with the aim of helping them to recognize and develop their strengths, pursue their passions and interests, and cultivate those skills that will enable them to be successful. My aim was not to point out flaws and weaknesses or to punish faculty for what they have not done, but to help them develop more awareness of what they are doing, to encourage growth, and to make available new opportunities for professional development. Perhaps then, I became a facilitator or guide in a more meaningful sense than I had previously understood myself to be. I learned that by listening to what they wanted to accomplish and hoped to become, as opposed to what I believe they need to do, shifted the focus to their own personal and professional development.

In early education (my area of expertise), we often make a distinction between a child’s actual development and his/her potential development. Actual development refers to the level at which a child is developing, or a measure of what the child has learned up to that point. Potential development, on the other hand, is a measure of what the child is capable of achieving or becoming. Vygotsky (Citation1978), for example, would point out that for a child to move beyond the level of actual development, she/he needs the support and guidance of a caring, responsive adult. While both teacher and child are engaged in the process, it is the teacher who must lead the way for such growth to occur in the classroom. The same is true of mentoring. Just as in Vygotsky’s theory both adult and child are changed (learn from) the process, both mentor and mentee are transformed. I have been changed through my mentoring of Christine and Mary and I believe I am a better leader as a result.

Discussion and implications

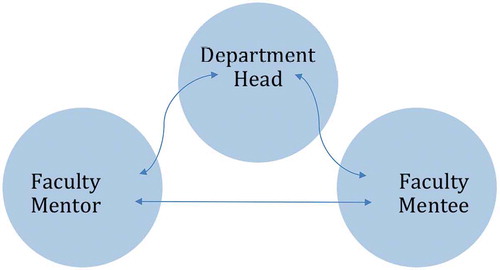

Thinking narratively allowed us to see our lives in motion, in relation to the developmental aspects of our identity formation as shifting and changing. University expectations can be overwhelming, complex, and demanding in various ways. Mentoring programs in institutions are often hierarchical and transactional rather than democratic systems (Johnson, Citation2007). Excellent mentoring relationships can evolve from mere transactional advising to more inter-relational and developmental mentoring through engaging in mutuality and advocacy. Developmental mentoring that is inter-relational in nature involves greater collaboration, reciprocity, and a concentrated focus on the mentee’s professional and career growth. Mentors who are relational see themselves as partners with their mentees, to assist them through the difficult developmental transitions. The institution was open to the three faculty engaging in an inter-relational, developmental mentoring framework although the initiative from the Dean’s office was one that entailed a more traditional mentoring relationship. As can be viewed in , although Andrew evaluated us, we all belonged to a network and collaborative community, a place where we could reveal ourselves to one other fully, be welcomed, and learn from and about one another in various manners. This figure illustrates how the developmental narrative space worked. Relationships are key in narrative inquiry and mentoring.

Creating and maintaining supportive and inclusive environments for new faculty is crucial for their success. Understanding this inter-relational developmental mentoring framework as a narrative inquiry through writing and dialogue over time, offered us an opportunity to examine our practices, beliefs, and growth processes in all areas of teaching, scholarship, and service. Although Christine left the university prior to applying for promotion and tenure, she received a job at a reputable university and Andrew continued to be her mentor. Christine and Andrew have continued their mentoring relationship through writing collaborations. They have co-authored a book chapter and journal article and presented their work at professional conferences. Mary received promotion to full professor, remained at the university and continues to mentor process with new faculty. Andrew is no longer a department head but has established a formational mentoring program for new faculty in their first three years.

These processes showcased a developmental approach to mentoring, a potential, useful tool for managing change processes for tenured faculty (mentors) and pre-tenured faculty (mentees) within an institution. This approach also offers opportunities for tenured faculty to share with new faculty the professional habits and values that are crucial for success within specific contexts. Faculty can embrace professional identity development, no matter what stage they are in their career, through trust and reciprocity. This research provides an empirical support as an alternative to hierarchical mentoring and offers the significance of cultivating developmental relationships to generate positive career outcomes. Chandlar and Kram (Citation2005) assert that due to the complexity of developmental relationships, more qualitative research is needed on how individuals utilize a developmental network and the impact the relationships have on their work. In this paper, we made such attempts to highlight the impact such a mentoring model had on us as individuals. Faculty members seeking non-traditional mentoring models could adapt a developmental network to fit their unique settings. However, further studies and explorations are needed across various institutional settings, to better inform the development of mentor and mentee relationships where a supervisor also serves as a mentor and the intricacies involved in such relationships.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Christine Nganga

Christine Nganga, EdD, is an Assistant Professor of Educational Leadership at George Washington University. Her teaching and research interests include leadership practice with a social justice and equity focus, narrative inquiry and mentoring theory and practice. Her work was been published in journals such as Educational Leadership Review, International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, and The Urban Review. She has also co-authored and authored several book chapters and presented her work in numerous national conferences.

Mary Bowne

Mary Bowne, PhD, is a Professor in Teaching, Learning, and Leadership in the College of Education and Human Sciences at South Dakota State University. Her research is in the area of teaching and learning with a particular emphasis in online and remote teaching strategies as well as curriculum. She has published numerous refereed articles, co-authored two book chapters, and presented at numerous conferences related to teaching and learning.

Andrew Stremmel

Andrew J. Stremmel, PhD, is a Professor in Teaching, Learning and Leadership Department in the College of Education and Human Sciences at South Dakota State University. His research is in the area of early childhood teacher education, in particular, teacher action research and Reggio Emilia-inspired, inquiry-based approaches to early childhood teacher education and curriculum. He has published over 60 refereed journal articles and book chapters, has co-edited two books and co-authored two books.

References

- Albrecht, T. E., & Bach, B. W. (1997). Communication in complex organizations: A relational approach. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace.

- Anafarta, A., & Apaydin, C. (2016). The effect of faculty mentoring on career success and career satisfaction. International Education Studies, 9(6), 22–31.

- Badali, S. (2004). Exploring tensions in the lives of professors of teacher education: A Canadian context. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 3(1), 1–16.

- Bin Tareef, A. (2013). The relationship between mentoring and career development of higher education faculty members. College Student Journal, 47(4), 703–710.

- Boyle, P., & Boice, B. (1998). Systematic mentoring for new faculty teachers and graduate teaching assistants. Innovative Higher Education, 22(3), 157–179.

- Cawyer, C. S., Simonds, C., & Davis, S. (2002). Mentoring to facilitate socialization: The case of the new faculty member. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 15(2),225–242

- Chandler, D. E., & Kram, K. E. (2005). Applying an adult development perspective to developmental networks. Career Development International, 10(6–7), 548–566.

- Clandinin, D. (2013). Engaging in narrative inquiry. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc.

- Clandinin, D. J., Pushor, D., & Orr, A. M. (2007). Navigating sites for narrative inquiry. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(1),21–35.

- Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (Eds.). (1999). Shaping a professional identity: Stories of educational experience. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (2000). Narrative inquiry. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- de Janasz, S. C., & Sullivan, S. E. (2004). Multiple mentoring in academe: Developing the professional network. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(2), 263–283.

- DoBrow, S. R., & Higgins, M. C. (2005). Developmental networks and professional identity: A longitudinal study. Career Development International, 10(6/7), 567–583.

- Downey, C. A., & Clandinin, D. J. (2010). Narrative inquiry as reflective practice: Tensions and possibilities. In Handbook of reflection and reflective inquiry (pp. 383–397). Boston, MA: Springer.

- Ehrich, L. C., Hansford, B., & Tennent, L. (2004). Formal mentoring programs in education and other professions: A review of the literature. Educational Administration Quarterly, 40(4), 518–540.

- Fries‐Britt, S., & Snider, J. (2015). Mentoring outside the line: The importance of authenticity, transparency, and vulnerability in effective mentoring relationships. New Directions for Higher Education, 171, 3–11.

- Gibson, S. K. (2006). Mentoring of women faculty: The role of organizational politics and culture. Innovative Higher Education, 31(1), 63–79.

- Guramatunhu-Mudiwa, P., & Angel, R. B. (2017). Women mentoring in the academe: A faculty cross-racial and cross-cultural experience. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 25(1), 97–118.

- Haggard, D., Dougherty, T., Turban, D., & Wilbanks, J. (2011). Who is a mentor? A review of evolving definitions and implications for research. Journal of Management, 37(1), 280–304.

- Hansford, B., Tennent, L., & Ehrich, L. C. (2002). Business mentoring: Help or hindrance? Mentoring and Tutoring, 10(2), 101–115.

- Harlow, R. (2003). “Race Doesn’t Matter, but … ”: The effect of race on professors’ experiences and emotion management in the undergraduate college classroom. Social Psychology Quarterly, 66(4), 348–363.

- Haynes, R. K., & Petrosko, J. M. (2009). An investigation of mentoring and socialization among law faculty. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 17(1), 41–52.

- Higgins, M. C., & Kram, K. E. (2001). Reconceptualizing mentoring at work: A developmental network perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 264–288.

- Ibarra, H. (1999). Provisional selves: Experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(4), 764–791.

- Jacobs, J. A., & Winslow, S. E. (2004). The academic life course, time pressures and gender inequality. Community, Work & Family, 7(2), 143–161.

- Jipson, J., & Munro, P. (1997). Deconstructing wo/men-toring: Diving into the abyss. In J. Jipson & N. Paley (Eds.), Daredevil research: Re-creating analytic practice (pp. 201–218). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Jipson, J., & Paley, N. (2010). Because no one gets there alone: Collaboration as co-mentoring. Theory into Practice, 39(1), 36–42.

- Johnson, K. S., Hastings, N. S., Purser, J. L., & Whitson, H. E. (2011). The junior faculty laboratory: An innovative model of peer mentoring. Academic Medicine, 86(12), 1577–1582.

- Johnson, W. B. (2007). On being a mentor: A guide for higher education faculty. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Johnson-Bailey, J., & Cervero, R. (2008). Different worlds and divergent paths: Academic careers defined by race and gender. Harvard Educational Review, 78(2), 311–332.

- Johnson-Bailey, J., & Cervero, R. M. (2002). Cross‐cultural mentoring as a context for learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2002(96), 15–26.

- Kapustin, J. F., & Murphy, L. S. (2008). Faculty mentoring in nursing. Topics in Advanced Practice Nursing, 8(4), Article ID 582904.

- Kashiwagi, D. T., Varkey, P., & Cook, D. A. (2013). Mentoring programs for physicians in academic medicine: A systematic review. Academic Medicine, 88(7), 1029–1037.

- Katuna, B. M. (2014). Breaking the glass ceiling? Gender and leadership in higher education (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.uconn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6581&context=dissertations

- Kram, K. E. (1988). Mentoring at work: Developmental relationships in organizational life. New York, NY: University Press of America.

- Lave, J., & Wengler, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation (Learning in doing: Social, cognitive and computational perspectives). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- McGuire, G. M., & Reger, J. (2003). Feminist co-mentoring: A model for professional development. NWSA Journal, 15(1), 54–72.

- McLean, S. V. (1999). Becoming a teacher: The person in the process. In R. P. Lipka & T. M. Brinthaupt (Eds.), The role of self in teacher development (pp. 55–91). Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Mullen, C. A. (2000). Constructing co-mentoring partnerships: Walkways we must travel. Theory into Practice, 39(1), 4–11.

- Mullen, C. A. (2005). The mentorship primer. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Mullen, C. A., & Forbes, S. A. (2000). Untenured faculty: Issues of transition, adjustment, and mentorship. Mentoring and Tutoring, 8(1), 31–46.

- O’Meara, K. (2015). A career with a view: Agentic perspectives of women faculty. The Journal of Higher Education, 86(3), 331–359.

- Palmer, P. (1997–2007). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (1988). Narrative knowing and the human sciences. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Rankin, E. A. (1991). Mentor, mentee, mentoring: Building career development relationships. Nursing Connections, 4(4), 49–57.

- Rice, R., Sorcinelli, M., & Austin, A. (2000). Heeding new voices: Academic careers for a new generation. Washington, DC: American Association for Higher Education.

- Sue, D. W., Lin, A. I., Torino, G. C., Capodilupo, C. M., & Rivera, D. P. (2009). Racial microaggressions and difficult dialogues in the classroom. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(2), 183–190.

- Suriel, R. L., Martinez, J., & Evans-Winters, V. (2018). A critical co-constructed autoethnography of a gendered cross-cultural mentoring between two early career Latin@ scholars working in the deep South. Educational Studies, 54(2), 165–182.

- Thomas, D. A., & Kram, K. E. (1988). Promoting career-enhancing relationships in organizations: The role of the human resource professional. In M. London & E. Mone (Eds.), The human resource professional and employee career development (pp. 49–66). New York: Green-wood.

- Tierney, W. G. (1997). Organizational socialization in higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 68(1), 1–16.

- Tierney, W. G., & Rhoads, R. A. (1994). Faculty socialization as a cultural process: A mirror of institutional commitment (ASHE-ERIC Higher Educational Report No. 93-6). Washington, DC: The George Washington University, School of Education and Human Development.

- Trower, C. A. (2012). Success on the tenure track: Five keys to faculty job satisfaction. Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press.

- Valian, V. (1999). Why so slow? The advancement of women. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Walker, J. A. (2006). A reconceptualization of mentoring in counselor education: Using a relational model to promote mutuality and embrace differences. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education, and Development, 45(1), 60–69.

- Wallace, J. E. (2001). The benefits of mentoring for female lawyers. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58(3), 366–391.

- Wasburn, M. H. (2007). Mentoring women faculty: An instrumental case study of strategic collaboration. Mentoring and Tutoring, 15(1), 57–72.

- Whitt, E. (1991). “Hit the ground running”: Experiences of new faculty in a school of education. Review of Higher Education, 14(2), 177–197.

- Wilson, R. (2001, January 5). A higher bar for earning tenure. Chronicle of Higher Education, 47(17), A12–A14.

- Yun, J. H., Baldi, B., & Sorcinelli, M. D. (2016). Mutual mentoring for early-career and underrepresented faculty: Model, research, and practice. Innovative Higher Education, 41(5), 441–451.