ABSTRACT

Measures aimed at newly qualified teachers (NQTs) in Norway are characterized by ambitious policy expectations, though with leeway for practitioners. This article investigates how NQTs perceive practices enacted to include them in the teaching profession while identifying the actors of such practices. We use practice architectures theory and the notion of ecology of educational practices to analyze conditions associated with mentoring and induction practice. Findings show that NQTs in Norway perceive mentoring and follow-up arrangements as limited and poorly adapted to their needs. We emphasize the need to take seriously tensions linked to mentoring practices, which become evident when NQTs problematize issues such as long-term temporary employment and school leaders as mentors. We argue for prioritizing mentoring practices and the closer follow-up of new teachers; the study illustrates how this may happen through better coupling between mentoring practices and other educational practices.

Introduction

Policy initiatives internationally and in Norway suggest that induction through mentoring is an important initiative in meeting challenges experienced by newly qualified teachers (NQTs). These challenges can be described as a ‘practice shock’ and include workload, stress, disillusion, and difficult working conditions, which may lead to NQTs leaving teaching (Halmrast et al., Citation2021; Veenman, Citation1984). Induction programs are implemented to counteract difficulties NQTs meet embarking on the teacher profession (Ingersoll & Strong, Citation2011). Mentoring is acknowledged as beneficial in these programs (Hobson et al., Citation2009; Ingersoll & Strong, Citation2011). However, the term ‘mentoring’ is used to describe a wide spread of initiatives directed at assisting NQTs, and generally, there is a lack of consensus about what mentoring is (Haggard et al., Citation2011; Kemmis, Heikkinen, et al., Citation2014).

Our understanding of mentoring has its point of departure in a document analysis of a Norwegian policy initiative describing mentoring as the central measure to help NQTs develop into professionals. The documents define mentoring as ‘a planned, systematic and structured process carried out individually and in a group’ (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training TDET, Citation2018). As such, this definition differs from the definitions commonly used in research articles and could cover a variety of structured processes. To better understand mentoring, a more typical definition is useful; we adopt the notion of mentoring as support of a novice (mentee) by a more experienced practitioner (mentor), designed primarily to assist in the development of the mentee’s expertise and to facilitate their induction into the profession and into the specific local context (Hobson et al., Citation2009, p. 207). Although this definition also opens for a variety of practices, it narrows mentoring down to arrangements where one person defined as a mentor and one as a mentee interact to assist mentee’s development and integration. In the Norwegian policy documents mentioned above, NQTs are understood as newly qualified teachers with zero to two years of experience. However, we have included newcomers who have been working longer because they are defined as NQTs by their employers. This is in line with research including NQTs with up to five years of experience (Hammerness, Citation2008; Lindqvist et al., Citation2014).

Teacher induction is support and development intended for those recognized as qualified teachers but without necessary experience; it can be further understood as the overall process in which mentoring is a part (Ingersoll & Strong, Citation2011). Internationally, induction programs vary extensively, and how and in which way mentoring is included varies as well (Ingersoll & Strong, Citation2011; Kemmis, Heikkinen, et al., Citation2014). The practices that NQT mentoring depend upon vary by context: differing educational policy expectations, teacher education, approaches to professional development, school culture, degree of teacher retention, and so forth (Kemmis, Heikkinen, et al., Citation2014).

The variety of mentoring and induction programs and perceptions have been addressed in several research contributions (Bickmore & Bickmore, Citation2010; Ingersoll & Strong, Citation2011; Kemmis, Heikkinen, et al., Citation2014; Spooner-Lane, Citation2016). Several studies have approached practices of mentoring through the theory of practice theory lens (e.g.Kemmis, Heikkinen, et al., Citation2014; Pennanen et al., Citation2016). Limited research is, however, invested in policy expectations and practices of enactment regarding policy intentions of mentoring of NQTs. The current contribution reports from a larger project investigating how Norwegian policy demands related to mentoring of NQTs in policy documents are perceived and operationalized in upper secondary schools by school leaders and mentors. Earlier findings from the documentary analysis of this project have indicated that policy documents encourage mentoring to be institutionalized as an integrated whole of the school organization and cultivated as part of arrangements for career-long collective learning (Jacobsen et al., Citation2023). The findings from interviews with school leader’s and mentors’ perceptions of actual mentoring practices in schools, however, indicate a considerable degree of diversity and distance between intended and actual practices to secure NQTs in schools (Jacobsen & Gunnulfsen, Citation2023). To add to the picture of policy demands related to mentoring of NTQs, the current article reports on investigations of how NQTs themselves perceive practices and relevant actors aiming to assist their integration into the teaching profession. The present article is guided by the following research questions:

How do NQTs perceive practices directed at them as newly employed novice teachers?

How do NQTs relate to the central actors involved in organizing practices directed at them as newly employed novice teachers?

The aim of the current article is to illuminate practices of organizing and leading mentoring and induction directed at NQTs. Hence, we are not interested in investigating the actual practices of mentoring and induction because this has been the focus of much research in many other contributions. Because we have established that mentoring and induction both may describe a variety of practices, the RQs open for an investigation of diverse initiatives and practices directed at accommodating NQTs’ needs, which may contain both mentoring and induction practices, as well as other practices.

An interconnected and holistic approach to practice (based on Grootenboer, Citation2018) guides our study as we zoom in and out on practices and surrounding arrangements included in the mentoring and induction of NQTs. Following this approach, we apply the theoretical framework of practice architectures (Grootenboer, Citation2018; Kemmis, Heikkinen, et al., Citation2014). Given the assumption that relational aspects are essential for NQTs to develop and flourish in schools (Kelchtermans & Ballet, Citation2002), we are interested in NQTs’ relations to relevant actors such as their leaders, mentors, and other colleagues, as well as to other practices and arrangements relevant for their perceptions of practices related to mentoring and induction.

Leading of induction practices may be understood through a concept of describing leadership suggested by Wilkinson and Kemmis (Citation2015) as orchestration of practices, which emphasizes that, rather than understanding leadership as something that is carried out only by principals, organizations are constantly being constructed and reconstructed through purposeful human activity, including the many actors and conditions involved in such activity. These actors may be middle managers, mentors or others. Middle leadership has been an increased focus for improving student learning and quality leadership since the first decade of 2000 (Pont et al., Citation2008). An expanded responsibility of middle leaders indicates widening the scope and including several actors when studying enactment of policy demands related to mentoring of NQTs (Abrahamsen, Citation2018).

The Norwegian context

In a Norwegian context, teachers are considered qualified for teaching after finishing their teacher education. In general, NQTs are entitled to some facilitation regarding their status as newcomers. In accordance with ‘The National Working Time Agreement,’ NQTs within their first year of employment after finishing their education are entitled to have a reduction in working time of 6% for preparation and professional updating unless something else is agreed. However, they are not legally entitled to receive mentoring. The policy demand about mentoring for NQTs may be characterized as a soft governance approach indicating a low-stakes accountability logic and involvement of teachers’ professionalism in decision making (Maroy & Pons, Citation2019). This soft governance policy approach provides freedom for local practitioners to enact policy ideas, such as NQT mentoring. The teachers are traditionally trusted in performing their professional practice (Gunnulfsen & Møller, Citation2021). On the one hand, freedom allows for local adaptation and creativity to establish sustainable local arrangements for mentoring NQTs. On the other hand, lack of requirements and economic means may represent challenges concerning establishing sufficient conditions for NQT mentoring in schools. The concept of ‘soft governance’ is relevant to understanding mentoring of NQTs in the Norwegian context.

Enabling and constraining induction and mentoring

We have already pointed to challenges in defining the concept of mentoring of NQTs and various understandings about what kind of practices mentoring and induction involve (Haggard et al., Citation2011; Hobson et al., Citation2009; Kemmis, Wilkinson, et al., Citation2014; Spooner-Lane, Citation2016). Such unclarity may indicate issues concerning what enables and constrains the organization of policy initiatives where both purpose and activity are unclear. Earlier research has shown that it is not sufficient to allot time for mentors to work with novice teachers (Wang, Citation2001); in a review study on induction and mentoring, Long et al. (Citation2012) found that school leader’s engagement is important for creating a structure supportive of the induction process through their impact on school culture, support of new teachers, and selection of mentors. More recently, Kutsyuruba (Citation2020) found that school leaders’ role in creating support for the mentoring process is determined by the school leaders’ focus on multiple levels: social, cultural, political, organizational, and individual. Kutsyuruba (Citation2020) pointed to essential features of enabling mentoring, such as school leaders’ involvement, communication with mentors and facilitating time for mentoring and creating supportive structures and awareness of roles and expectations. The issue of role clarity points to some challenges, for example, regarding evaluative aspects present in mentoring and induction, and the dual role of school leaders as both supporters and evaluators, which can raise difficulties for NQTs, for example, regarding further employment (Ingersoll & Strong, Citation2011; Kemmis, Heikkinen, et al., Citation2014). Enabling factors to support sustainable NQT mentoring arrangements are educated mentors who are found to enact leadership regarding organization of policy-initiated mentoring as they recontextualize their knowledge as mentors into new social practices and problem-solving in schools (Willis et al., Citation2019).

Significant research relevant to illuminating the organizing of mentoring – reporting primarily from English-speaking contexts where implementation of induction programs often has a point of departure in state-/government policy and mentoring is related to teacher assessment (Hobson & Malderez, Citation2013; Mullen, Citation2011). Although the Norwegian soft governance context can be interpreted as more encouraging than demanding with few high stakes when it comes to NQT mentoring, issues of assessment and quality assurance are present. A Norwegian study showed how dilemmas concerning the mentor role may arise when school leaders carry out mentoring, as they often do (Lejonberg, Citation2018). An example is if the school leader gets information through the mentoring that may affect further employment. Another Norwegian study showed how Norwegian principals are not engaged in mentoring of NQTs as a professional activity, and many principals considered NQTs’ needs primarily as of a practical sort, like needs for information, rules, and routines (Sunde & Ulvik, Citation2014). Research, however, also showed the potential of NQTs as contributors in developing the professional community (Jakhelln et al., Citation2021). However, NQTs are torn between perceiving themselves as resources and needing help and support (Kvam et al., Citation2023). In this situation, support from the leadership level is crucial for the NQTs to feel valued (Amundsen, Citation2009), and mentors may be key actors to ambassador the NQTs as contributors in the professional community (Lejonberg et al., Citation2022).

The mentioned studies showed different aspects of school leaders’ and mentors’ roles related to mentoring of NQTs; however, the current study zooms in on practices and practice architectures in the organizing of induction and mentoring of NQTs (Kemmis, Heikkinen, et al., Citation2014; Wilkinson & Kemmis, Citation2015) and on how NQTs relate to central actors involved in organizing practices directed at them as newly employed novice teachers. We add to research applying a practice lens on the organization of mentoring of NQTs (Kemmis, Heikkinen, et al., Citation2014; Pennanen et al., Citation2016; Wilkinson & Kemmis, Citation2015), and by focusing on policy expectations and practices of enactment regarding mentoring of NQTs, we address an area that has seen a limited focus in research.

Theoretical approach

Our theory lens is practice architecture theory, as elaborated by, for example, Grootenboer (Citation2018), Wilkinson and Kemmis (Citation2015), and Kemmis, Wilkinson, et al. (Citation2014). Theory of practice architectures may shed light on the dialectical interaction between individuals and system and how certain conditions or arrangements (practice architectures) enable practices and vice versa. Our approach to practices has its point of departure in NQTs’ perceptions of practices and actors involved in induction and mentoring initiatives.

Based on Kemmis, Wilkinson, et al. (Citation2014), we conceptualize practice as situated and social and consisting of what is said, done, and how people relate to one another in a specific project of a practice (Kemmis, Heikkinen, et al., Citation2014). The project of practice encompasses the aim motivating the practice, the actions (sayings, doings, relatings), and the ends aspired through the practice. In the present study, the project we look for is practices in supporting and developing NQTs in their first years of teaching.

Locally, at the schools in which data for this article was collected, several set-ups were developed to facilitate mentoring of NQTs. These set-ups were concrete frameworks, like time, place, and amount of people involved in the mentoring and must be understood in relation to the arrangements that prefigure a practice and that can both enable and constrain the practice. Set-ups and arrangements are both concepts utilized to denote practice architectures (see Grootenboer, Citation2018, p. 50). Arrangements can be denoted as cultural-discursive, material-economic, and social-political arrangements, and together, these arrangements establish the practice architectures (Kemmis, Wilkinson, et al., Citation2014). Cultural-discursive arrangements could, for example, be the general discourse at the workplace, which are often expressed in language or thoughts and that enable and constrain sayings; material-economic arrangements could, for example, be buildings, rooms, or organization of classrooms that become visible or expressed through activity or work and may enable or constrain the doings; and the social-political may, for example, be employment policy, issues of funding that often become visible through solidarity and power and that may enable or constrain the relatings. The mentioned arrangements are theoretical concepts that, in reality, are not possible to separate. However, they may serve as categories to explore NQTs’ perceptions of practices of induction and mentoring, actors involved, and arrangements that provide or limit mentoring and induction practices.

When applying sayings, doings and relatings to our empirical data, ‘sayings,’ what is said or thought about mentoring of NQTs at the working place, may illuminate common cultural mindset related to mentoring of NQTs. ‘Doings,’ understood as what and how things are done concerning NQT mentoring at a specific moment and in a particular place, could illuminate how initiated policy intended to cultivate NQTs’ integration into the teaching profession are set out in real life. The term ‘relatings’ is understood as relationships among actors, between practices, and also between actors and arrangements. Insights on relatings could illuminate how NQTs relate to central actors such as their mentors, leaders, and other colleagues, but also how they relate to the arrangements prefiguring the mentoring and induction practices. Theory of practice architecture provides an approach to scrutinize the practice landscape and local circumstances in which the practice of organizing mentoring of NQTs is taking place. According to Grootenboer (Citation2018, p. 51), ‘ … any form of educational reform … must also simultaneously attend to the enabling and constraining practice architectures as they [the reform] are realized in the particular site’. In the current contribution, we zoom in on NQTs’ perceptions of such practice architectures, that is, arrangements and practices related to policy initiatives (reforms) of mentoring NQTs.

To answer RQ1, we looked for descriptions of arrangements and practices maintaining and challenging NQTs’ integration into the profession. These features can include norms, ways of talking, ideas, opinions, and descriptions of how, when, and where things are done. To answer the second RQ, we have looked for elaborations in informants’ statements about actors and practices in mentoring and induction initiatives, along with how the NQTs relate to these. These elaborations illuminate relations between actors such as NQTs, mentors, and leaders.

Finally, we have adopted the concept of practice ecologies from theory of practice architecture. Ecologies of practices illuminate relationships between practices and how they are interconnected (Grootenboer, Citation2018). This approach has potential to illuminate practices of mentoring of NQTs as interwoven with and challenging other educational practices in a school. This approach will be particularly elaborated upon in the discussion.

Methodology

Data gathering

To illuminate NQTs’ perceptions of practices related to mentoring of NQTs, we have adopted a qualitative design. Interviews were conducted to provide in-depth insights into NQTs’ perceptions of practices of organizing induction and mentoring. Primary data consist of qualitative interviews carried out with eight NQTs in four different upper secondary schools. Upper secondary schools were selected because such schools have been found to provide diverse mentoring practices (Halmrast et al., Citation2021). In addition, the schools’ written plans for mentoring of NQTs worked as supplementary data.

In the current study, interviews were conducted individually with the NQTs, specifically with two informants from each school. Our informants ranged from very recently employed to five years of experience, and six out of eight were temporally employed. The individual interviews were carried out digitally via Zoom because of pandemic restrictions on school visits. Video data were deleted immediately after the interview, and only audio data was utilized in the analysis. All data were transcribed and anonymized. A semistructured interview guide was utilized to ensure some basis for comparability across cases while allowing exploration of the phenomenon (Maxwell, Citation2013). Initially, the term ‘mentoring of NQTs’ was used in the interviews to ask for arrangements and practices of interest; however, follow-up questions were adapted in response to the variety of organization and set-ups described as practices established to support NQTs, which was typically not limited to a narrow definition of the term mentoring. Three of the four schools had plans for the mentoring and induction of NQTs, whereas the fourth school did not have a written plan.

The organization of mentoring and induction was practiced differently in the four schools, and the data provided a basis for dividing the schools’ practices of NQT mentoring into two models, which could be an approach associated with the most similar systems design (MSSD) (Anckar, Citation2008). This strategy implies a selection of schools that are as similar as possible, except regarding the phenomenon under scrutiny (Anckar, Citation2008). The first model schools (called Model 1) provided structured one-to-one mentoring for NQTs led by an educated mentor, whereas the second model schools (called Model 2) provided group mentoring for NQTs led by a middle leader and were characterized by a less structured approach toward mentoring. Although this presentation is a simplification and could compromise differences between the schools within one model, we considered it to be a useful way of highlighting essential differences between approaches in the given context. The approach also contributed to securing data anonymity.

Table 1. Overview of Informants and the mentioned measures in Model 1 and Model 2 are presented in .

Steps in the analysis

Data were subjected to thematic analysis inspired by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). A first reading was conducted to get familiar with the data regarding NQTs’ perceptions of practices targeted at them as a group and their relations with leaders and mentors in these practices. The complexity and diversity in perceptions of practices of induction and mentoring in all the schools was striking in and across the schools, calling for a theoretical approach providing a framework that emphasizes how practices of mentoring and induction emerge under different conditions like cultural-discursive, material-economic, and social-political arrangements. The framework of practice architecture was adopted for this purpose. A second reading was guided by the theoretical concepts of sayings, doings, and relatings as codes to explore the different practices of induction and mentoring. In a third and fourth reading, the two authors individually and through discussions conducted a more fine grained analysis to scrutinize the dialectics between the categories of sayings, doings, and relatings with the practice architectures interwoven with practices in the empirical material. In this process, inductive themes emerged, and the theoretical codes were discussed regarding these inductive themes. The themes were discussed with other researchers and adjusted several times.

Below is a table presenting an overview of codes with definitions and empirical examples. The presented codes were applied throughout the material, and quotes were chosen to exemplify and challenge the categories, as elaborated on in the findings section.

Table 2. An overview of codes with definitions and empirical examples of quotes from NQTs asked about the practices of induction and mentoring are presented in .

Findings

In the following, we present our findings in light of cultural-discursive, material-economic, and social-political arrangements, all related to NTQs’ perceptions of practices and conditions enabling or challenging NQT mentoring and induction. The first two arrangements are especially relevant to illuminate NQTs’ perceptions of practices directed at them as newly employed novice teachers (RQ1). The notion of social-political arrangements, however, is especially relevant to illuminating which actors NQTs perceive as central in the practices of mentoring and induction and how NQTs relate to these actors (RQ2).Footnote1Footnote2Footnote3

Cultural-discursive arrangements: the discourse of mentoring NQTs

The notion of cultural-discursive arrangements sheds light on how mentoring is understood and discussed by the informants. From Model 1, one NQT described the practice of receiving a mentor and knowing that this is an established practice (which is both communicated in written plans and orally) as follows: ‘I think it is very good that it is systematized. I think it’s a good follow-up of new teachers.’ This quote, representing Model 1, indicates that the actors in this model experience mentoring practices enabled by a notion of mentoring as systematic and predictable structures. This organization is also embedded in local plans at the schools performing Model 1, presenting mentoring and induction practices as structured and established.

For Model 2, however, the analysis of cultural-discursive arrangements reveals a contrasting finding related to how mentoring is understood and discussed in the schools. This became evident, for instance, in relation to the use of the term mentoring. We recognized how, when asked about the mentoring, several of the informants answered with descriptions of a variety of activities and set-ups. This is illustrated by a quote from an informant in a Model 2 school where the interviewer was following up on a response, asking the informant to elaborate on why she called her leader ‘a mentor.’ The informant expressed that she perceived the leader as ‘a kind of mentor, because I always ask her about everything, and she is always able to answer me.’ The quote illustrates how mentoring can be perceived by NQTs, illuminating how the term ‘mentor,’ as well as ‘mentoring’ is used by NQTs about different types of help and support from a leader, colleague, or buddy. The following quote, which is an answer to how the NQT perceive the organization of mentoring of NQTs at the school, may expand the insight on how the term mentoring can be interpreted:

Yes, exactly ‘mentoring.’ … there has been a lot of mentoring since I started working here—introduction to different systems, which platforms they use, and then, I got a buddy. Otherwise, it has been a lot on my own, but I have received an extremely large amount of help.

This quote indicates how cultural-discursive arrangements in the form of norms and common understanding of the term mentoring is more in line with what is usually denoted ‘induction’ in research may maintain current practices for supporting NQTs in Model 2 schools. For instance, mentoring is understood as introducing NQTs to systems and structures. Data from Model 2 schools in a plan for induction and mentoring emphasize the teacher team, not a mentor, as the crucial support of NQTs. As such, the written material collected from the schools supported the interpretation of the possible rather vague notion of mentoring in the given context.

The notion of cultural-discursive arrangements can show the insights of a discourse in Model 2 schools characterized by rather random and vague perceptions of mentoring. For instance, exemplified by a quote elaborating that the reason for establishing a group meeting for NQTs was because of the influence from regional educational authorities:

I think it [the group mentoring] was initiated because we went to this regionally initiated meeting about mentoring of NQTs, and the representative from the leadership group realized that many other schools had a much more extensive arrangement for mentoring NQTs than we did. As we had nothing. At least, that’s what I think was the reason.

This quote shows the constraining practices of mentoring and induction. For instance, an NQT from a Model 2 school experienced that she was not informed that she was appointed a buddy; it was something she found out by accident: ‘He [the buddy] hasn’t said anything to me about him being my buddy, and there has been nothing organized around it. I only found out that he was my buddy by coincidence.’

Another NQT in a Model 2 school expresses something similar: ‘We were assigned a mentor or a buddy, eh, and it was the good old “and if you wonder about something, just ask!” It was very poorly organized.’ Indeed, the empirical data have also exemplified critical comments illustrating how NQTs perceived that central actors in Model 2 schools lack understanding related to induction and mentoring:

My buddy is surprised every time that I didn’t know this or that, but I didn’t even know that existed. So, I would have liked it if we had a way to ensure that everyone got the follow-up they needed. Something a little more structured.

This quote illustrates how the cultural-discursive arrangements supporting the status quo, as elaborated on above, can be challenged by NQTs.

Material-economic arrangements: conditions for NQT mentoring

The notion of material-economic arrangements enabled us to illuminate the structures and conditions maintaining and challenging practices of induction and mentoring of NQTs. Diversity characterizes the practices developed and maintained to accommodate NQTs needs in the investigated empirical material. The investigated plans revealed that Model 1 schools provided a more structured plan for mentoring of NQTs than in Model 2.

Relevant material-economic arrangements visible in Model 1 schools indicate how structures for mentoring enabled mentoring situations where NQTs were being observed by a mentor in class and discussing the situation afterwards.

It is surprisingly positive, and the mentor gives valuable feedback. Without it being a very all-encompassing scheme, it’s sort of collegial and conversation-based … you get valuable insights from someone who sits at the back of the class and sees everything … it has changed how I do things … So I have to say, it has exceeded all expectations so far.

The material-economic arrangements surrounding the mentoring of NQTs expressed in Model 1 are centered around the teaching and provide practices also revolving around this practice.

Several of the NQT informants in Model 2 schools, however, described how they experienced being largely left to themselves: ‘I got a list, and some recommendations how to use the equipment and such, but most of it, I had to figure out myself … So that took a lot of time in the beginning.’ In such cases, getting help depended on their own initiative, as described by one informant, ‘I’ve been a lot on my own, but I have received plenty of help when I’ve asked for it,’ or as described by another informant in a Model 2-school, ‘On my initiative, we sometimes discuss the teaching situation after class in these parallel-teacher set-ups.’ These findings can illustrate how the notion of material-economic arrangements brings insights into how the lack of plans can constrain structured mentoring practices.

The data from Model 1 schools, however, also indicated how the material-economic arrangements, such as structures for employment or whether the setup for mentoring fit into their teaching schedule, can challenge mentoring practices. For instance, one of the NQTs in a Model 1 school expressed frustration related to these constraints: ‘I miss out a lot since I teach at the time when the group meetings take place. … ’

Another issue concerning including NQTs in mentoring and induction practices in Model 1 was regarding the percentage of the position the NQTs had. This issue was pinpointed by an NQT:

I still don’t have a permanent position; it is contract based. I have stepped in and out for several years. … And it was only this spring that I worked 100% for the first time, and now, I am down to 75% again. Getting a steady job in a school is not easy.

In Model 2, as described by the NQTs, group mentoring was organized outside of working hours and led by formal school leaders. Material-economic arrangements such as the time schedule of NQTs and school leaders were mentioned by informants as conducive to this mentoring practice. The setup of this afternoon group meeting was apparently organized in such a manner for convenience and practical reasons. One of the NQTs in a Model 2 school expressed this opportunity for mentoring as being of the utmost necessity, although the NQT would have appreciated if it took place during daytime:

… I have very strong opinions about asking us to meet up after working hours. At the same time, I am very much in need [of a meeting place like this]. I am very grateful for it, and I would rather do it for free than have that offer disappear. But it’s yet another example of us having to work a little for free.

The NQT expressed how such arrangements were related to a feeling of investing more in the job than what was paid for. Such material-economic arrangement was described as not ideal for NQTs, but the practices associated with these arrangements were maintained because there were no other alternatives, and the NQTs accepted and embraced what they were offered.

Material-economic arrangements for mentoring and induction practices seem very different both in Models 1 and 2. However, the mentoring set-ups in both cases may be described as weak in the sense that mentoring of NQTs may not be of highest priority, and other practices within the schools were prioritized before mentoring, for example, teaching practices or administrative practices.

Social-political arrangements: NQTs’ relatings to colleagues

The notion of social-political arrangements shed light on the relations NQTs had to actors central in mentoring practices and how social-political arrangements can contribute to maintaining or challenging practices directed at NQTs. In Model 1 schools, the relationship between NQTs and mentors was described by several informants as being important but somewhat peripheral: ‘It is seldom we talk [the NQT and the coordinating mentor].’ This indicates that the social-political arrangements were characterized by distance but also by mutual respect. The latter appeared when one of the NQTs in a Model 1 school emphasized that it was a good thing that the mentor was not a close colleague but someone coming into the classroom to help her develop the actual work with the students: ‘Then, I know I am provided with a fresh set of eyes, focusing on how I interact with the students.’

This quote could indicate that social-political arrangements around the mentoring may facilitate purposeful mentoring for professional development because the mentor was considered an outsider to the NQT, providing ‘fresh eyes’ and potentially neutrality and no role in assessing the work of the NQT.

The NQTs from Model 2 schools were concerned about what NQTs in a temporary position may request regarding support, as emphasized in the following citation by an NQT:

It is easy for me to say [that I can speak freely] as I have a permanent position here, and I do not think that any of the other new teachers have that. So, then I talk from the perspective of greater job security.

This statement indicates that job security was essential for how NQTs related to their mentors and leaders, exemplifying how social-political conditions can contribute to maintaining practices, especially given that NQTs restrict themselves from sharing their actual opinions. How the matter of power and relations may also represent challenges for NQTs was illustrated in another Model 2 school where an NQT was hesitant to criticize the school leadership for how they organized mentoring and induction practices:

I don’t know how fortunate it is that it is the good people from the leadership group who are in charge of these meetings, but I think it is difficult to complain too much about it because they have so many things to think about.

This statement can indicate that the relationship between NQTs and formal school leaders is asymmetric and characterized by NQTs’ submissive approach where the NQT took the (self-imposed) responsibility to not bother school leaders about the issue of the quality of this group meeting for NQTs.

In Model 1 schools, several informants expressed the importance of their autonomy: ‘ … I like feeling that no one is observing or judging me all the time, but that they trust me.’ ‘No, I’m quite self-motivated so … for me I like to figure things out myself.’ These findings could indicate that social-political arrangements facilitating much autonomy for NQTs can be perceived as a conduct of trust. On the other hand, the benefit of structures or arrangements facilitating autonomy may be challenged by how NQTs in schools in both models experience tough workloads and find their responsibilities overwhelming. Expressions like the following illustrate these thoughts: ‘And you’re never done with work. We’re talking many evenings, many weekends where you sit perhaps on the phone or follow up on students or parents, because you are unable to set boundaries’ (NQT, Model 2 school). When NQTs described working extending regular working hours and responsibilities stretching far outside of the classroom, the notion of power and relatings can be relevant to understand why they did not complain.

The structures for following up NQTs have been emphasized as beneficial for NQTs; however, we also have findings illuminating how some social-political arrangements meant to support NQTs may also create tensions in the support of NQTs. This comes through in a statement from an NQT in a Model 1 school, where one of the schools did not provide released time for NQTs because this region had a special working time agreement allowing the schools to include the released time in the mentoring: ‘I thought new teachers were entitled to reduced teaching time the first year, but I have been told [by the leadership] that is not the case.’ The agreement between the school and regional authorities brought light to the social-political arrangements challenging the practice of supporting NQTs by concretizing that NQTs were supposed to get mentoring in their released time, implying that they may not freely avail themselves of such a benefit as released time. The tension concerns how NQTs may have perceived such an arrangement as a restriction of their autonomy as professional actors, despite their appreciation of a predictable structure with mentoring for follow-up in Model 1 schools.

Although the findings, as presented, indicate that the NQTs experienced heavy workloads in both models, they also expressed feeling valued as resources: ‘It feels like there is a genuine interest [from the leadership] and I get the feeling that I am considered a resource at the school.’ The NQTs also expressed appreciation for the support and proximity of the principal or middle manager or colleagues. An example from a Model2-school illustrates this: ‘The principal is really … we see him all the time. … I like that he feels very available … he is on our side, and we are a team.’ Also, relations to the head of department and colleagues were mentioned by several of the informants as significant, something that can be illustrated with this quote from a Model 2 school.

I have both the middle manager and the colleagues who are easy to talk to, which means that I dare to ask them questions about what I find difficult. If I hadn’t had that and there was nothing [mentoring] organized, then I wouldn’t have progressed in my job.

Thus, relations to school leaders were considered crucial, enabling practices that NQTs found supportive and relevant for their professional development.

The findings also indicate how NQTs perceived variation in relationships between leaders and NQTs, as expressed in the following quote from a Model 2 school:

I have a very good head of department, so she is very easy to talk to … we are lucky because, in the other departments, they have perhaps a head of department who is not in the office that much and they get a bit uh … sort of worried when that person comes in. While our leader, she is very present all the time. But that’s her style.

This statement shows that this head of department established a practice to promote the support of her department by actively taking part in their daily conversations, whereas this was not perceived as the case in other departments. The notion of relatings in this matter can illuminate how different leadership practices can be established within the same workplace and the same social-political arrangements.

Discussion

The investigation of perceptions of practices in our material (RQ1) indicates that induction and mentoring can include several types of practices not well defined and structured. Issues of power and symmetry were also visible in how the NQTs related to central actors involved in organizing practices directed at them as newly employed novice teachers (RQ2). The practice architectures surrounding mentoring of NQTs in the schools in the material did not accommodate expectations from policy documents, suggesting a more structured organization of mentoring NQTs integrated in schools’ project of professional development, promoting NQTs as resources in the professional community and mentors and school leaders as drivers of interorganizational collaboration (Jacobsen et al., Citation2023). Such bold policy expectations were also challenged by data from leaders and mentors expressed in a recent study connected to the overall project of which the present study is a part. The mentioned study (Jacobsen & Gunnulfsen, Citation2023) has shown school leaders are not particularly aware of the policy demand for mentoring but instead trust the professional community and teacher team to take care of the NQTs.

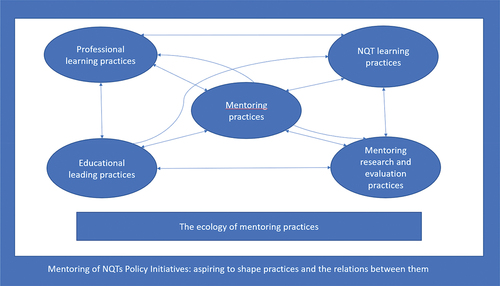

To shed some further light on our findings in the discussion, we have utilized the concept of ‘ecologies of practices,’ which assume that many educational practices are developed in and across work contexts and are interconnected, enabling and constraining each other (Grootenboer, Citation2018). To illuminate practices of mentoring of NQTs in the ecology of educational practices, we illustrate such dynamics in below.

Figure 1. The ecology of mentoring practices is based on Kemmis, Wilkinson, et al. (Citation2014) and Grootenboer (Citation2018).

Placing mentoring practices in the middle of the figure illustrates the complexity and interconnectedness between subpractices in an organization. Our findings show how mentoring practices in one school may be well developed but isolated from other professional learning practices. The figure visualizes that all subpractices are interwoven, and interconnectedness between leading practices and other practices, such as mentoring practices, could facilitate more integrated relations in the professional community. A call for interconnectedness is also supported by other researchers suggesting sustainable mentoring to be a built-in part of learning communities and schools’ organizational structures (Hobson & Maxwell, Citation2020; Mullen, Citation2011).

Leaders leaving to the professional community to take care of the NQTs indicated a lack of interconnectedness between educational leading practices and the other subpractices in the ecology of mentoring. Indicated weak connections could be understood in light of the Norwegian educational context, where professional autonomy is emphasized at the same time as government interference in professional practices has become ‘a key part of Norwegian educational reform practices’ (Gunnulfsen & Møller, Citation2021). Such conflicting forces can be regarded as troublesome to deal with. Furthermore, accountability mechanisms regarding NQT mentoring are not high-stake, leaving to the local practitioners how to perform such a policy demand (Jacobsen et al., Citation2023). Our findings indicate that both perceptions of professional autonomy and accountability mechanisms have consequences for the local practice architectures in which mentoring and induction practices emerge. Such findings are relevant with regard to a US-context where mentoring is a mandated policy mechanism which, according to Mullen (Citation2011), ‘can turn mentoring into a mere achievement measure for schools (p. 65)’ supplying principals with a tool for assessment of NQTs. Similar features are reported from a UK-context by Hobson and Malderez (Citation2013), with the introduction of the verb ‘judgementoring’ illustrating NQT mentoring as assessment in a high-stakes policy context. The policy-context thus provides a basis for discussing enabling and disabling conditions for mentoring practices. A relevant question to ask is how much policy involvement is necessary for providing beneficial mentoring for the NQT? Mentoring as a reform strategy does not necessarily imply sustainability of professional practices (Mullen, Citation2011).

The lack of sufficient means to carry out the expected policy is another relevant aspect of the disconnectedness of mentoring. Norwegian educational authorities fail to provide economic means to organize mentoring of NQTs in upper secondary schools, and this may be detrimental to the priority of NQT mentoring. Lack of adequate funding is an issue also brought up in other research from other countries (e.g. Hobson & Maxwell, Citation2020; Mullen, Citation2011).

In Norwegian policy documents, the authorities suggested connecting mentoring of NQTs to other practices of professional development in schools; however, the findings from Jacobsen and Gunnulfsen (Citation2023) indicated that NQT mentoring is ‘a precarious practice’ disconnected from other practices. The practices of policymakers and school leaders are crucial in realizing policy intentions and depend upon insights into the complex ecology of mentoring practices. If research indicating how mentoring practices may contribute to NQTs’ professional development are known by policy developers nationally, as well as leaders forming practices locally in the different schools, this research could be made an object of discussion and investigation to form better practices for mentoring of NQTs, focusing on improving the connection of practices within a school both from a policy and practice aspect.

Mentoring as it is described by NQTs in this article’s data material seems to cover all types of follow-up, and these perceptions of mentoring mirror the general description of mentoring presented in Norwegian policy documents, which mostly have not described what mentoring practice consists of. Our findings indicate that the term mentoring is a broad array of activities and practices. The notion of cultural-discursive arrangements sheds some light on the discourse surrounding NQT mentoring. Examples are that arrangements, such as social activities for NQTs and collaboration in teams, seem to be perceived as relevant by the NQTs when asked about mentoring. It seems plausible to interpret that mentoring as a ‘one-to-one support of a novice (mentee) by a more experienced practitioner (mentor)’ (Hobson et al., Citation2009) is not generally what ‘they talk about’ when asked about mentoring of NQTs, at least in our study. The discrepancy is not necessarily a problem; however, the lack of precise terminology related to the issue can be relevant to understanding the challenges perceived by NQTs in the practice field. Our findings indicate that the NQTs were generally thankful for the support they received, even though they thought there was room for improvement. Asymmetry and power can represent challenges for NQTs to present demands or be critical toward existing practices. This became particularly visible in Model 2 schools where there was a lack of clarity concerning what kind of support the NQTs may expect.

The practices described in our material can be challenged by research indicating that beneficial mentoring practices, for instance, can include work structured to develop mentees’ competence by setting goals, discussing how to reach them, concretizing, and challenging beliefs about learning and teaching, while mentors provide feedback on mentees’ teaching (Hobson et al., Citation2009; Schwille, Citation2008). Although these processes probably can appear in a variety of practices like those indicated by the presented findings, it seems reasonable to underline the importance of leaders and policymakers facilitating processes actually found to contribute to NQTs’ professional development. Stronger interconnectedness between the subpractices in , such as between mentoring research and educational leading practices, could drive a more critical and nuanced understanding of what mentoring is and how it should be practiced. Alternatively, more concrete definitions of policy initiatives could provide actors in the ecology of mentoring practices with a clearer understanding of what it implies to form mentoring practices.

Our findings regarding the conceptualization of NQT mentoring resonate with the findings in a review study by Spooner-Lane (Citation2016), in which mentoring NQTs was found to not be sufficiently defined, thus indicating a weak knowledge base for implementing NQT policy initiatives. Our findings call for a more conscious approach to the organization of mentoring, which is in line with how Spooner-Lane (Citation2016) pointed out the importance of clarifying a purpose for mentoring, as well as a shared understanding of what kind of a practice it is. Our work contributes to this picture by introducing the notion of disconnectedness between practices in the ecology of mentoring to illustrate the described challenges.

The notion of material-economic arrangements brings forth how structures can enable or challenge mentoring practices. Preliminary employment of NQTs and little time and resources to organize mentoring are examples of arrangements expressed as challenging for NQTs who did not receive mentoring in Model 2 schools and who missed it, while those who experienced a more structured follow-up by a mentor in Model 1 schools appreciated such practices. In the latter, both principals and mentors were involved in the design and structure of the mentoring organization. The notion of material-economical arrangements illuminates school leaders’ practice as essential for developing and maintaining beneficial structures, which seems to be in accordance with research about successful mentoring of NQTs (Kutsyuruba, Citation2020).

To answer the second research question, we elaborated on how NQTs related to central actors involved in organizing initiatives directed at them as NQTs. The focus on social-political arrangements and relatings has highlighted actors and situations essential for NQTs. Several of the NQTs in our material perceived their middle managers as their mentors. In general, research about the role of mentors indicate challenges for mentors of NQTs to provide sustainable mentoring for the mentee regarding the focus of the mentoring and the relationship between the mentor and the mentee (Hobson & Malderez, Citation2013; Kemmis, Heikkinen, et al., Citation2014; Heikkinen et al., Citation2018). Such challenges may also arise in situations where formal leaders or mentors are mentoring as a means of assessment, which can challenge developmental practices. This is, according to Mullen (Citation2011), often the case in the US. Although the Norwegian policy directions regarding mentoring of NQTs suggest that mentoring should be distinct from the leading of NQTs, an evaluation of the mentoring of NQTs in Norway reports that 33% of NQTs are mentored by the principal (Rambøll, Citation2016). Such a situation has been problematized in research addressing different aspects of school leaders being involved in NQT mentoring, as for instance the asymmetric relationship between the school leader and the NQT, and the amount of tasks and relationships a school leader must manage, as well as the power a school leader posesses within the organization (Lejonberg, Citation2018). Issues of power are an essential element when interpreting findings regarding school leaders’ involvement in practices of NQT mentoring The NQTs in our material were hesitant to criticize the school leadership for how they organized mentoring and induction practices, which may indicate that NQTs are strategic in their communication with leaders. Findings from earlier research have shown that, when being assessed, mentees may be strategic and careful in presenting their uncertainties and vulnerabilities, which can hamper the beneficial outcome of mentoring (Hobson & McIntyre, Citation2013). Educated mentors who seem to be well aware of this situation are suitable resources for negotiating and organizing formalized mentoring programs (Willis et al., Citation2019).

In sum, our findings illustrate how NQTs can feel left to themselves and that they could benefit from more organized support and acknowledgment of their demanding situation. Mentoring was organized in the studied schools, though the ecology of mentoring practices seemed characterized by a lack of connectedness, hampering the potential of school-based mentoring of NQTs.

Limitations and further research

An aim of practice architecture theory is to illuminate the potential for change (Wilkinson & Kemmis, Citation2015) because theory enables the study of arrangements that enable or constrain change of practices. The empirical material in studies theoretically based in practice architectures is often characterized by multiple methodological approaches that can enlighten situations from several angles and that may facilitate the ability to describe change. Our single method study could have benefitted from more detailed and processual information from the situations, discourses, and relations the NQTs have described. An avenue for further research would thus be to further investigate how practices described in our material fold out in school, for instance, by adding observation for mentoring, leader meetings about mentoring, and study of plans for mentoring to elaborate on how practices are maintained and challenged.

Concluding remarks

Our findings have indicated that NQTs perceived initiatives directed at them as vague and limited. Furthermore, middle managers and colleagues played crucial roles in initiatives regarding their situation. Issues of power were visible in the organization of induction activities, and the NQTs appeared submissive in such matters. Implications for practice are that school leaders and mentors should scrutinize weak organization of induction and mentoring of NQTs, as expressed by a vague perception of what mentoring is, but also for how the practice of NQT mentoring plays out. The theory of practice architecture provides a promising lens for visualizing how practices in leading of induction are intertwined with issues of policy (legislation), economy, knowledge, time, resources, habits, and school culture.

The success of well-intended policy ideas about mentoring of NQTs hinges on their practicality and alignment with the real-world needs and constraints faced by practitioners. The findings elaborated on here can indicate the potential of developing a stronger connection between subpractices interwoven in the ecology of mentoring practice. Policy initiatives can serve as a resource in these efforts, given that policymakers pay attention to the need for integrated practices and the relations between them.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Eyvind Elstad and Eli Ottesen at The Department for Teacher Education and School Research for helpful comments and valuable help with finishing the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The table is based on information from NQTs and formal plans for mentoring from the schools.

2 In all the schools, both NQTs and the newly employed are appointed a buddy who has responsibility to help out with practicalities and socialization.

3 One middle manager was under mentor training in the period the interview was carried out.

References

- Abrahamsen, H. (2018). Redesigning the role of deputy heads in Norwegian schools – tensions between control and autonomy? International Journal of Leadership in Education, 21(3), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2017.1294265

- Amundsen, P. (2009). Å være nyutdannet lærer, behovet for veiledning og organisering av veiledning i skolen.

- Anckar, C. (2008). On the applicability of the most similar systems design and the most different systems design in comparative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11(5), 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570701401552

- Bickmore, D. L., & Bickmore, S. T. (2010). A multifaceted approach to teacher induction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4), 1006–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.043

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Grootenboer, P. (2018). The practices of School Middle Leadership - Leading Professional Learning. Springer.

- Gunnulfsen, A. E., & Møller, J. (2021). Production, transforming and practicing ‘What Works’ in Education–The Case of Norway. What Works in Nordic School Policies? Mapping Approaches to Evidence, Social Technologies and Transnational Influences. Educational Governance Research. (pp. 87–102). Springer.

- Haggard, D. L., Dougherty, T. W., Turban, D. B., & Wilbanks, J. E. (2011). Who is a mentor? A review of evolving definitions and implications for research. Journal of Management, 37(1), 280–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310386227

- Halmrast, H. H., Gulbrandsen, I. P., Sjøvold, J. M., Stampe, P. L., Ulvik, M. O. K., & Karin/Rambøll, E. (2021). Evaluering av veiledning av nyutdannede nytilsatte lærere - sluttrapport.[Evaluation of mentoring of newly qualified teachers - final report] Utdanningsdirektoratet. https://www.udir.no/contentassets/8f74754444124fe5b3e93415b7472180/sluttrapport_evaluering-av-veiledning-av-nyutdannede-nytilsatte-larere.pdf

- Hammerness, K. (2008). “If you don’t know where you are going, any path will do”: The role of teachers’ visions in teachers’ career paths. The New Educator, 4(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/15476880701829184

- Heikkinen, H. L., Wilkinson, J., Aspfors, J., & Bristol, L. (2018). Understanding mentoring of new teachers: Communicative and strategic practices in Australia and Finland. Teaching and Teacher Education, 71, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.11.025

- Hobson, A. J., Ashby, P., Malderez, A., & Tomlinson, P. D. (2009). Mentoring beginning teachers: What we know and what we don’t. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(1), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.001

- Hobson, A. J., & Malderez, A. (2013). Judgementoring and other threats to realizing the potential of school‐based mentoring in teacher education. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 2(2), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-03-2013-0019

- Hobson, A. J., & Maxwell, B. (2020). Mentoring substructures and superstructures: An extension and reconceptualisation of the architecture for teacher mentoring. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(2), 184–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1724653

- Hobson, A. J., & McIntyre, J. (2013). Teacher fabrication as an impediment to professional learning and development: The external mentor antidote. Oxford Review of Education, 39(3), 345–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2013.808618

- Ingersoll, R. M., & Strong, M. (2011). The impact of induction and mentoring programs for beginning teachers: A critical review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 201–233. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311403323

- Jacobsen, H. M., & Gunnulfsen, A. E. (2023). Dealing with policy expectations of mentoring newly qualified teachers–a Norwegian example. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2023.2250381

- Jacobsen, H. M., Jensen, R., & Lejonberg, E. (2023). Tracing ideas about mentoring newly qualified teachers and the expectations of school leadership in policy documents. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 26, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2023.2218110

- Jakhelln, R., Eklund, G., Aspfors, J., Bjørndal, K., & Stølen, G. (2021). Newly qualified teachers’ understandings of Research-based Teacher education Practices−Two cases from Finland and Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 65(1), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1659402

- Kelchtermans, G., & Ballet, K. (2002). The micropolitics of teacher induction. A narrative-biographical study on teacher socialisation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(1), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00053-1

- Kemmis, S., Heikkinen, H. L. T., Fransson, G., Aspfors, J., & Edwards-Groves, C. (2014). Mentoring of new teachers as a contested practice: Supervision, support and collaborative self-development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 43, 154–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.07.001

- Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Edwards-Groves, C., Hardy, I., Grootenboer, P., & Bristol, L. (2014). Changing practices, changing education. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Kutsyuruba, B. (2020). School administrator engagement in teacher induction and mentoring: Findings from Statewide and District-Wide Programs. International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership, 16(18), n18. https://doi.org/10.22230/ijepl.2020v16n18a1019

- Kvam, E. K., Roness, D., Ulvik, M., & Helleve, I. (2023). Newly qualified teachers: Tensions between needing support and being a resource. A qualitative study of newly qualified teachers in Norwegian upper secondary schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 127, 104090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104090

- Lejonberg, E. (2018). Bør ledere være veiledere for nyutdannede lærere? En problematisering basert på teori om profesjonalitet og etisk bevissthet. Nordvei, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.15845/ntvp.v3i1.1481

- Lejonberg, E., Jacobsen, H. M., & Mangen, O. T. (2022). Ledelse av profesjonsfellesskapet: Å anerkjenne nyutdannede lærere som ressurser. Skolelederen, 2 (2), 22–25.

- Lindqvist, P., Nordänger, U. K., & Carlsson, R. (2014). Teacher attrition the first five years – a multifaceted image. Teaching and Teacher Education, 40, 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.02.005

- Long, J. S., McKenzie-Robblee, S., Schaefer, L., Steeves, P., Wnuk, S., Pinnegar, E., & Clandinin, D. J. (2012). Literature review on induction and mentoring related to early career teacher attrition and retention. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 20(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2012.645598

- Maroy, C., & Pons, X. (2019). Introduction. InC. Maroy & X. Pons (Eds.), Accountability policies in education - a comparative and multilevel analysis in France and Quebec. Cham: Springer (pp. 1–13). Springer.

- Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Sage publications.

- Mullen, C. A. (2011). New teacher mentoring: A mandated direction of states. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 47(2), 63–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/00228958.2011.10516563

- Pennanen, M., Bristol, L., Wilkinson, J., & Heikkinen, H. L. T. (2016). What is ‘good’ mentoring? Understanding mentoring practices of teacher induction through case studies of Finland and Australia. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 24(1), 27–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2015.1083045

- Pont, B., Moorman, H., & Nusche, D. (2008). Improving school leadership (Vol. 1). OECD Paris.

- Rambøll. (2016). Veiledning av nyutdannede barnehagelærere og lærere: En evaluering av veiledningsordningen og veilederutdanningen. [Mentoring of newly qualified teachers: an evaluation of the mentoring program and the mentoring education]. Utdanningsdirektoratet. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/tall-og-forskning/rapporter/2016/evaluering-av-veiledningsordningen-sluttrapport.pdf

- Schwille, S. A. (2008). The professional practice of mentoring. American Journal of Education, 115(1), 139–167. https://doi.org/10.1086/590678

- Spooner-Lane, R. (2016). Mentoring beginning teachers in primary schools: Research review. Professional Development in Education, 43(2), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2016.1148624

- Sunde, E., & Ulvik, M. (2014). School leaders’ views on mentoring and newly qualified teachers’ needs. Education Inquiry, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v5.23923

- The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (TDET). (2018). Mentoring of Newly qualified teachers - How to carry it out (Veiledning av nyutdannede - Hvordan kan det gjennomføres). https://www.udir.no/kvalitet-og-kompetanse/veiledning-av-nyutdannede/hvordan-kan-det-gjennomfores/

- Veenman, S. (1984). Perceived problems of beginning teachers. Review of Educational Research, 54(2), 143–178. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543054002143

- Wang, J. (2001). Contexts of mentoring and opportunities for learning to teach: A comparative study of mentoring practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(1), 51–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00038-X

- Wilkinson, J., & Kemmis, S. (2015). Practice theory: Viewing leadership as leading. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 47(4), 342–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2014.976928

- Willis, J., Churchward, P., Beutel, D., Spooner-Lane, R., Crosswell, L., & Curtis, E. (2019). Mentors for beginning teachers as middle leaders: The messy work of recontextualising. School Leadership & Management, 39(3–4), 334–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2018.1555701