Abstract

This study will provide some inspiration and practical insights to academic libraries and educators within tertiary education who wish to experiment with digital upskilling programmes in their institutions. 2,661 students registered for extra-curricular digital skills workshops over a three-week period in the spring of the 2021 academic year, at a time when Covid19 meant that students were already spending a lot of time learning online. Focus groups conducted with workshop attendees revealed their motivation and some of the benefits that accrued to them from participating in the digital skills workshops. This study provides a blueprint for academic libraries who wish to develop or collaborate on digital skills programmes and reflects on how a refresh of library workshops to emphasize digital literacy skills can not only meet the contemporary learning needs of their students but also boost the attendance at other, more traditional library workshops.

This study will

outline how a collaboration on digital skills provision can benefit both libraries and students

describe how topics were selected for the digital skills workshops

discuss how the workshops were delivered and how this method of receiving digital skills instruction was perceived by students

report on attendance rates and how traditional library workshops experienced a ‘boost’ when offered as part of a digital skills series

address limitations of the study and make recommendations for further research.

Introduction

In 2017 the EU reported that 44% of Europe’s citizens did not have basic digital skills (EITCI, 2017). The digital literacy landscape did not improve significantly in the four years since. The EU’s Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) reported in its analysis of Europe’s digital performance in 2020 that a large part of the EU population, which includes higher education students, still lacks basic digital skills (European Commission, Citation2020a). Ireland is the most improved country in Europe in terms of its DESI scores, for its advances since 2015 in the digitization of its economy and society, but Europe still faces a shortage of digital experts and signaled last year that a massive investment in skills is needed (European Commission, Citation2020b). Ireland published a National Digital Strategy in 2013 (Department of Communications & Energy & Natural Resources, Citation2013) and a 10-year literacy strategy for Ireland was published in July Citation2021 (Department of Further & Higher Education, Research, Innovation & Science, 2021). The latest strategy sets out to “decrease the share of adults in Ireland without basic digital skills from 47% to 20%” (Department of Further & Higher Education, Research, Innovation & Science, 2021). In a characteristically candid commentary, Fintan O’Toole wrote in the Irish Times in May Citation2021 that “no one is safe when half of us are digitally illiterate” (O’Toole, 2021). A lack of adequate digital competence is a barrier for economic and social prosperity across the EU. By tackling global challenges and equipping graduates with the skills that they need to contribute to society, universities have a role to play in developing the digital skills of their students.

Background

The University of Limerick (UL) offers undergraduate to PhD level programmes to 17,000+ students across each of the primary academic disciplines. UL is currently ranked in the top 200 Universities worldwide for graduate employability (QS, 2021). 2,200 students a year are placed within UL’s global network of employers across five continents in the University’s ‘Cooperative Education’ programme. The inclusion of this mandatory work experience within academic programmes is part of UL’s foundational approaches to education and signals to students and employers that upskilling is a feature of the student experience at UL. Being closely aligned with the world of work means that UL students and educators are keenly aware of the need for new skills to be learned and taught, and as such, this series of digital skills workshops was a contribution by the library to the University’s strategic goal of addressing regional and national skills needs (University of Limerick, Citation2019).

Supporting digital literacy of university students

In late 2019, Ireland’s first National Digital Experience Survey (INDEX) was conducted. The survey identified that 38% of students had opportunities to review and update their digital skills (National Forum, 2020, p. 63). What about the other 62%? Could the library’s workshops provide a way for students to improve their digital skills?

JISC’s framework (JISC., Citation2015) identifies the fundamental literacies that students need to learn to be digitally capable. These capabilities informed models such as Ireland’s All Aboard Metro Map, with learning pathways for students to acquire new digital skills (National Forum, 2015). The library considered the ways it could respond to the unmet digital literacy needs identified by students in the INDEX survey in early 2020. The JISC framework along with recurring student questions from the library’s query resolution service, about academic referencing, literature searching, and source evaluation informed this discussion and helped us to determine the main topics of the digital skills workshops. The library also experimented with some creativity topics and offered these eight workshops in the spring digital skills series in 2020:

Setting up a final year project library for your referencing

Smart searching for information

How to spot fake news; tips on critically evaluating information sources

Notetaking in a digital world

Making great posters using free software

How to be seen by mastering the meme

Introduction to graphic design

Working securely online – protecting your digital identity

2020 Digital skills pilot at the library

Workshops on each of the eight topics identified above took place in a library computer lab on campus, were offered on a drop-in basis, and were taught in-person in February 2020. The attendance was 107 students over three weeks. We attributed the relatively poor turnout to the timing within the academic year; the first three weeks of the academic year is a busy settling in period at UL. We knew we had only reached a tiny proportion of the target audience. Within a month, the Covid19 lockdown of higher education amplified the importance of and need for ubiquitous digital skills.

2021 Digital skills workshops offered by library, ITD & CTL

Digital literacy levels were a concern before Covid19 but came into sharp focus during the pandemic. A report from Ireland’s Quality and Qualifications body, QQI, in August Citation2020 noted that “learners with low levels of digital skills or learning difficulties found it difficult to engage with, or benefit from, remote teaching and learning” (QQI, 2020, p. 57). Recognizing that digital literacy was still a challenge for students who were forced in to a new way of learning since March 2020, the library looked again at ways it could support digital literacy. Given its staffing levels and priorities, the library could not scale up the digital skills offerings on its own. To expand the series to offer more topics, the library invited colleagues from UL’s Center for Transformative Learning (CTL), the Information Technology Division (ITD) and Marketing and Communications (MarComms) to contribute workshops in 2021. This broadening of expertise would expand the library’s 2020 pilot digital skills programme and allow the library to remain a lead partner and deliver crucial information literacy alongside digital skills upskilling opportunities for students. Given that the University’s academic delivery model for 2021 was largely online, the digital skills workshops were delivered virtually in 2021.

Topics & timing

Workshop topics for 2021 were expanded based on what we had learned from the National Forum’s INDEX survey, with input from the IT Division about recurring student queries and the insights of the EDTL project that is working with the National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning on understanding student’s digital capabilities and needs. The series ran three weeks later than the 2020 series, in academic weeks 4, 5 & 6, after students had settled in to university.

Software

Where practicable, we selected free tools such as Canva and Audacity in favor of proprietary tools that might present an access barrier for students. We focussed on openly available image repositories for our Copyright Free Images workshop. We also used University-supported platforms like the Microsoft Office suite, and MS Teams, EndNote and Panopto to demonstrate essential technologies that support academic work.

Duration & delivery mode

Each of the workshops was thirty minutes long and was delivered live on Microsoft Teams. This was a conscious decision on behalf of the library so that the workshops were short and therefore more appealing and accessible. Students were invited to sign up for repeat sessions of workshops and could attend as many or as few of the workshops as they wished. Our experience with running hour-long sessions is that they can sometimes clash with a lecture or can just feel too long for attendees. Delivering short sessions was an attempt to give more people a chance to attend in what is already a busy time of the year, mid semester. In the workshop evaluations, participants suggested slightly longer workshops for some topics e.g., Powerpoint, Excel and posters. For some of the practical sessions like Excel, Word and Powerpoint the attendees were given a resource document in advance so that they could work through the instructional session with the presenter in the workshop. There was a lot of material to cover in a short amount of time, so the feedback is valid about session length for some of the topics.

Moderated sessions

Many of the sessions had a facilitator in attendance, in addition to the main presenter. This proved invaluable, providing a different and personal/professional perspective and was essential for moderating the discussion on the chat which the presenter can’t monitor when sharing their screen and presenting. The presenters often stayed on the call with attendees beyond the thirty minutes and dealt with questions there, and after.

Synchronous delivery with recordings

Recordings and the workshop slides were shared with the attendees on the same day and stored on a Microsoft Stream channel for later viewing. The workshops took place over a three-week period, thirteen topics each week, but even with this distributed approach students felt that the workshops could have been spread out a little more. This is valid feedback and will form part of the considerations when we discuss sustainability in the conclusions in this paper. Workshop resources used by all presenters were shared on an open platform for student learning and for reuse in teaching by faculty members.

Literature review

In his foreword to the 2020 JISC Student Digital Experience Insights Survey report, Sir Michael Barber writes “it is essential that students receive practical support to develop their digital skills, both to ensure they progress academically as well as in preparation for the careers of the future” (JISC., Citation2020, p. 3). The JISC Digital Experience Insights survey is critical to the higher education sector’s understanding of its students, as it relates to digital experiences. In Ireland, in the academic semester immediately prior to the Covid19 pandemic, the first ever Irish National Digital Experience (Index) Survey (National Forum, 2020) was conducted. The findings of this survey provided important information about students’ digital skills levels. According to a Times Higher Education report “Universities must be at the center of this national movement to create the next generation of highly skilled, adaptable, innovative and digitally literate graduates entering the workforce” (Times Higher Education, Citation2021). It is crucial therefore that, as part of a University structure, libraries play a role in creating digitally literate students.

Academic librarians teach students the fundamentals of discovering, creating, and managing information. This is referred to as information literacy and there are many definitions of this concept within the literature. One widely used definition allows us to explain and connect Information Literacy (IL) to its 21st century cousin, Digital Literacy (DL). The definition provided by the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP) for information literacy offers us the terminology to begin to see the overlap and natural extension of IL to DL in library instruction:

“Information literacy incorporates a set of skills and abilities which everyone needs to undertake information-related tasks; for instance, how to discover, access, interpret, analyze, manage, create, communicate, store and share information” (CILIP, Citation2018).

“the ability to find, evaluate, utilize, share and create content using information technologies and the internet”.

The Open University’s Digital and Information Literacy Framework tells us that both digital and information literacy are “underpinned by critical thinking and evaluation” (The Open University, Citation2019). Library workshops, whether they have an IL, or a DL focus teach students to discover, evaluate, create and manage online content. Hallam, Thomas, and Beach (Citation2018, p. 46) tells us that “although young people live in an online connected world, research indicates that as students, their abilities to locate, contextualize and utilize digital resources for the purposes of learning cannot be assumed”. Library workshops are designed to address this skills gap among students.

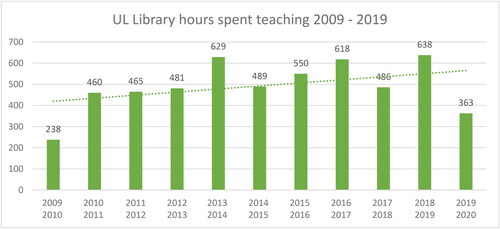

The library staff at the University of Limerick deliver hundreds of hours of student instruction per year, reaching over 70,000 students with these classes in the past decade (). Martzoukou (Citation2021, p. 275) claims that “the COVID-19 pandemic stressed even more the important role of academic librarians in helping students to develop information, digital and media literacy skills”. The increased demand for library workshops as recorded in the digital skills series described in this study will no doubt be reflected in future returns to SCONUL (Society of College, National and University Libraries) Annual Library Statistics platform.

The noticeable drop in 2019/2020 was related to a maternity leave where teaching hours fell as a result and due to a change in the way first year students received library instruction. The drop in 2017/2018 was related to staff changes, and the absence of 2 critical posts for a period of time while recruitment took place to replace librarians who moved on from the University.

It is reasonably well established in the literature that academic libraries have a role to play in student digital literacy. Examples of student digital literacy initiatives with library involvement include Cardiff University’s DigiDOL project (Cardiff University, Citation2013), the London School of Economics’ SADL project (Secker, Citation2014), Deakin (Owen, Hagel, Lingham, & Tyson, Citation2016), Monash university libraries’ digital skills work (McLeod & Torres, Citation2020) and London South Bank University Library’s initiative with their university’s digital skills trainers, cited in Corrall and Jolly (Citation2019, p. 118).

It is evident to higher education practitioners, librarians, and others, that students enter a rapidly evolving digital-technologies world when they begin their third level education. As reported in Martzoukou (Citation2021) “as academic libraries move forward, they have a renewed mission to help learners in the online space to become both information rich and digitally competent”.

Methodology

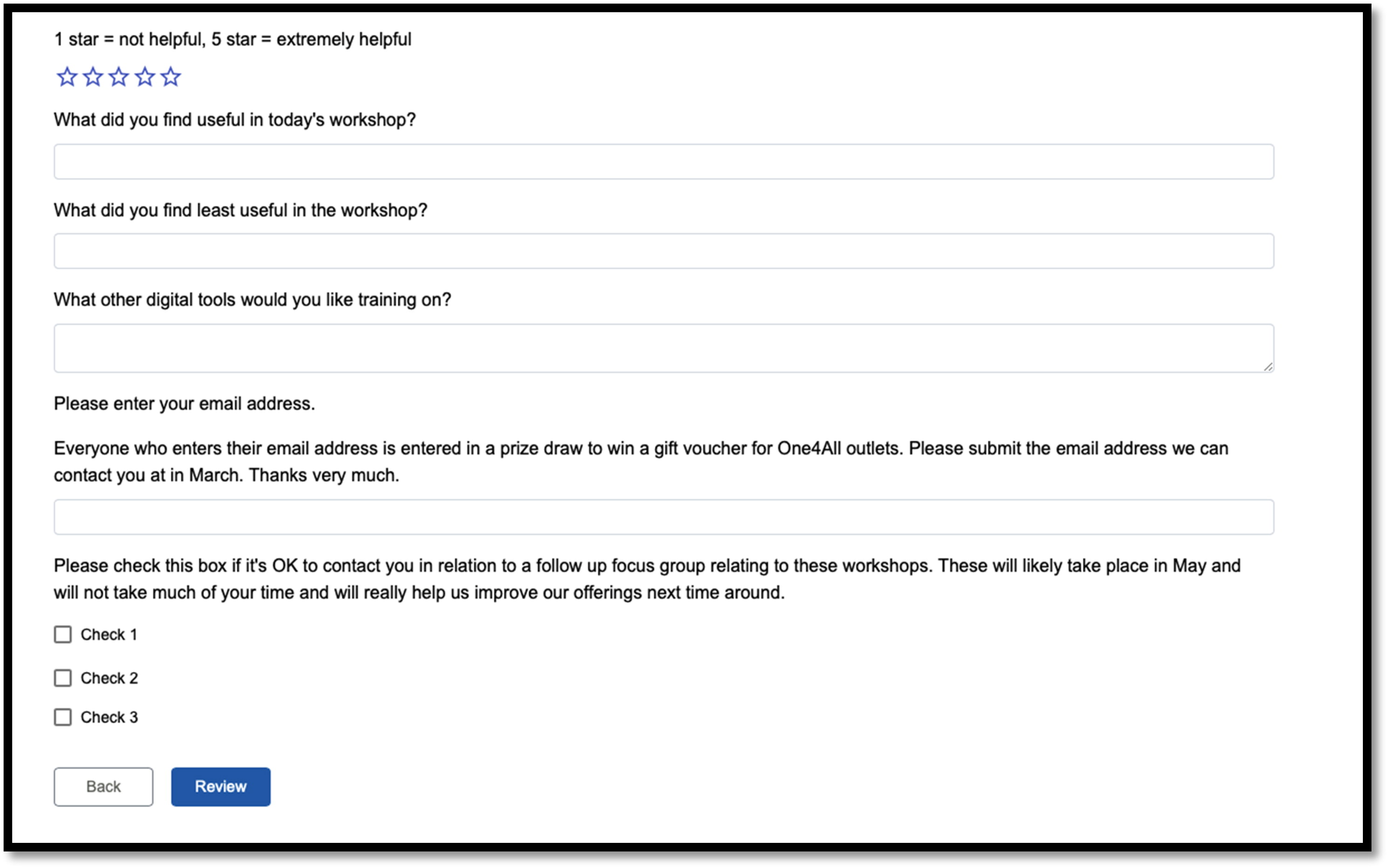

The researchers selected a case study approach that would allow us to describe and analyze our experiences within this project. Yin’s (Citation2008) definition of a case study as “investigating a contemporary phenomenon in its real-life context” lends itself to this research. As we would use multiple sources of evidence, both quantitative and qualitative, this research method would give us a data richness to allow us to present observations that addressed both the “how” and “why” of what happened during this project. Within the study we took a mixed-method approach, employing both surveys and focus groups methods to gather data. A mixed methods approach allows a certain amount of triangulation of data, the focus groups in this study were used, as described in Flick (Citation2009) as a second approach for data collection. Some demographic information was collected through the registration process as student email addresses were required to do follow-up. The data was gathered through and is securely stored on the Springhare LibCal application. The data collected was only used for the purposes of this study and to plan future enhancements. Immediately after the workshops, a short online evaluation survey (see Appendix 1) was sent to participants to gather early reactions to the content. These evaluations were issued in Weeks 4 & 6, so that participants did not feel “over-surveyed”. The researchers were able to offer small incentives to six of those that completed the evaluations, we felt this was a necessary motivation to have people complete the evaluations as our experience of using online evaluations of workshops is that the response rate can be low. This survey asked students to rate the usefulness of the workshop and to highlight other topics they would like to have training on.

The focus group method generates data or information within the small group setting which when analyzed can help in planning and making decisions. (Glitz, Citation1997). The data from the online surveys informed the topics we probed within a focus group where we gathered qualitative commentary from participants about their motivation for attending and to discuss their learning arising out of the workshops. The focus group convener conducted the focus group in early May 2021 and participants gave informed consent to participate in the anonymous discussion. A set of questions was prepared by the researchers (see Appendix 2) and the focus groups reported on their views on the digital skills workshops under several headings. Within the discussion section of this paper, we report the views of eight students, representing both undergraduate and PhD students and have indicated in quotation marks where it is the voice of the student, as distinct from the researcher’s commentary.

This research received ethics approval in the university’s ethics approval process.

Findings

There was a 1,000% increase in attendance at the digital skills workshops, delivered virtually, in 2021 compared to a year earlier (). One might assume that online delivery was the explanation for the significantly higher attendance rates, but we will see from the focus group feedback in the discussion that online delivery was not the sole or single factor determining why students signed up for the workshops in 2021.

Table 1. Attendance figures for University of Limerick’s digital skills workshops in 2020 and 2021.

In this study, we discovered that traditional library workshops such as Searching Library Databases attracted larger numbers when offered as part of a wider skills programme than it did as a standalone offering. On the six occasions that this session ran in AY 2020/21 the average attendance was 12 students. When offered as part of the digital skills series, it had an average attendance of 28 students. Regrettably, we were not able to offer the Introduction to Graphic Design in 2021 as the subject expert we collaborated with from the University’s Marketing and Communications Division was unavailable due to other work commitments. It is particularly regrettable that this content did not feature in spring 2021, given the types of additional training that students indicated they were interested in when asked what else they would like training on (see p. 8).

The workshops attracted a total of 2,661 signups over the three weeks. The overall attendance rate was 54% of total signups. The library managed a vibrant communications and outreach campaign including the creation of branded workshop logos, social media videos, campus emails and reminders. The library has had Student Peer Advisors employed in the library for over 10 years now and these students are a crucial part of our student engagement activities. They delivered promotional videos about the workshops on Snapchat and Instagram. Weekly student emails resulted in hundreds of signups. Emails to faculty were also important, as we will discover in the discussion later, as lecturers encouraged their students to attend the workshops. The Learning Technologists Forum on campus was very supportive of the initiative and circulated details University staff twice during the three weeks and colleagues in the Center for Transformative Learning and ITD also helped to promote the series through their social media channels.

Workshop evaluations

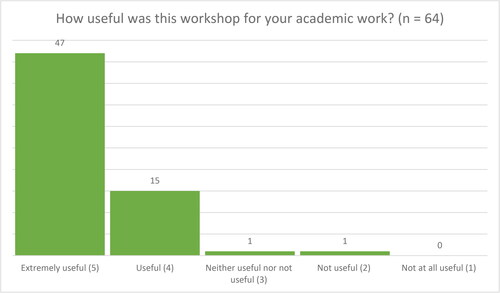

Of the 68 people who completed the workshop evaluations, 64 answered the question ‘Was this workshop useful for you in your academic work’ on a ranked scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being not at all useful and 5 being extremely useful. Of the 64 responses, 97% of respondents indicated that the workshop was either useful or extremely useful (). An evaluation of the qualitative feedback from people who didn’t find the workshops useful indicated they wanted longer workshops or wanted a more in-depth treatment of the topic.

Figure 2. Participant evaluation of how useful the digital skills workshops were for their academic work.

When asked what else they would like training on people asked for “anything related to improving assignments” and training on the following tools/techniques ().

Table 2. What other digital tools/techniques students would like workshops about.

Focus group findings

Commentary that is directly attributable to focus group participants is in quotation marks throughout this section for ease of reference

In addition to the sizeable increase in student attendance at these workshops in 2021, the insights gathered in the evaluations and the student focus group provides valuable guidance for libraries as they plan student workshops. The main takeaway for libraries from this research is that the topics the library teaches in its workshop series’ appeal to a student’s curiosity, they want to know more about a topic if they see that the university library is offering training on it. Focus group participants in this study reflected that “they would attend the classes whether they were delivered online or in a classroom on campus”. This needs to be tested in the future when we hope students will return to on campus learning. Participants said they “liked having the opportunity to engage with other students, and the presenters, and make connections that would benefit them in their studies”. They also liked having recordings of classes made available afterwards. Within each of the questions, there are additional insights that libraries may find instructive when planning their content for workshops.

How do students usually learn new digital skills?

We know from observing how students work and practices on the ground that students go to YouTube or other online sources when they need to learn how to do something. This is confirmed in Moghavvemi, Sulaiman, Ismawati, and Nafisa Kasem (Citation2018) study where they found that “many students rely on YouTube to solve academic problems and answer any questions they might have”. Understanding this user behavior is part of UL Library’s motivation for creating ‘How To’ videos for our YouTube channel (Glucksman Library Youtube Channel, 2021). Visuals and worked examples that feature in YouTube videos seem to be a popular way to learn. The workshops provided worked examples using resources shared in advance of the sessions and recordings that students could watch back later at a time that suited them. Focus group participants noted a difference between YouTube videos and our workshops when they said “the workshops were more dynamic than a YouTube experience as the workshops were conducted live and allowed participants to ask questions during the session”. Students value these interactive sessions and as we will see from later discussion on online workshops, the ability to have both this synchronous learning experience coupled with a recording of the session gives students with varying learning styles more options. PhD students in particular value “the relationships that can emerge from attending a live workshop, where a follow up or one to one can be arranged with an expert”. Students told us that they are not inclined to ask their lecturers when they need assistance with technology. Rather, “they will seek advice from their friends or peers”, but it is lecturers in some cases that referred their students to these digital skills workshops, as we will hear about in the next section.

Why did students attend these workshops?

Given the substantial increase in attendees in 2021 compared to 2020, we wanted to understand more about why 2,661 students signed up to the digital skills workshops. Why would students voluntarily register for more virtual learning given that they had spent a year in an unanticipated online learning environment? The focus group responses provide food for thought for libraries who wish to develop programmes like ours. The focus group participants helped us to understand that it was “the strength of the programme” that motivated them to register. Students told us that “the workshop topics were a good match to what we wanted”. Following our notices to campus mailing lists and extensive advertising on Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat, UL lecturers recognized the value of the workshops and encouraged their students to sign up for them. One lecturer explicitly told their students, and this was reported to us in the focus group, that “UL was investing in these workshops to help them improve the standard of their academic work”. Some lecturers attended the workshops and others requested sessions for their students. Given the time pressures and workload for academics, the digital skills workshops filled an unmet need on campus, for both students and academics. In our conclusions, we will return to the issue of sustainability in this regard and describe how we were not able to provide additional workshops beyond the three weeks “burst”.

The focus group students also cited “a desire to build their own skill set and understand UL academic best practice”. Some participants attended the workshops “to remind themselves of things they hadn’t used when on Cooperative Education (‘Co-op’) work placement”. Their Excel and Word skills were fine as they had used these tools while on ‘Co-op’ but students “welcomed the refresher on academic tools like Panopto and EndNote”. Other students cited curiosity as a motivating factor to attend.

Participants noted that the library at UL has a strong reputation on campus for delivering workshops that students find useful. A PhD student in the focus group remarked that she had attended a lot of library workshops during her studies, and they were “tremendously helpful”. The library’s workshops have, according to her, “built her skills and confidence and saved her time in her academic work”, with the library’s workshops aligned clearly with the student’s needs. In addition to the digital skills workshops, this PhD student mentioned how beneficial she had found a library workshop that “taught her about adding the SciHubX extension in her browser”.

Feedback from the focus group said that word of mouth on campus told other student networks about the workshops; this corresponds with what we saw in the registration forms in the second and third weeks where people responded increasingly that they had heard about the workshops from their friends.

If the workshops were delivered in person, would you still have attended?

When planning for future digital skills series, it was important for the researchers to establish if the exclusively online delivery of the workshops was a factor in the high attendance rates.

The online delivery of workshops meant that students could attend from anywhere in the world. The “provision of the workshop slides and resources used in the workshops and the subsequent sharing of the recording of the event” was also a feature of the series that appealed to students. It is less common to have an “in-person” workshop recorded so, for the students, “online delivery is a preference but not the sole deciding factor”. One focus group participant remarked that “if they were on in Dublin, I’d have got on a bus and traveled there to attend them”. Dublin is a two-hour drive from the University of Limerick.

We are very aware that people could be suffering from “online” fatigue and there may be an element of nostalgia when people say they would go to campus to attend an in-person workshop on digital skills. But there is a strong suggestion from the focus group participants, particularly for the PhD students, that “it was the topics being presented that were the most significant factor in workshop attendance”.

Did it matter to you who was presenting the workshop?

The students we discussed this with in the focus group were agreed that “it is the presenter’s expertise that matters most” in the presentation of the digital skills workshops. The students said “it didn’t matter to them if the instructor was from the Library or ITD or academic staff if the person was knowledgeable and engaging”. According to the students, the expertise of the presenters was evident throughout the workshops. Instructors were able to answer all questions asked and anything they could not answer on the day was followed up afterwards with additional information. One of the focus group participants remarked that “it was not unusual that the library was involved in this series as he remarked that the library is more than just a place to borrow books”; he has used it for referencing help during his studies for example.

They commented that “having student presenters in some of the sessions was reassuring”. They knew that the student had a shared experience with them. Student instructors were empathetic toward the attendees and shared tips based on their own learnings about academic tools.

Did you find the workshop useful?

Handwritten notes that people took in the sessions, along with the attachments shared during follow up queries on referencing for example, plus the recordings and workshop material including workshop slides are proving to be an important knowledge base for workshop attendees. They felt that the workshops “put them on the right track, with referencing in particular”. They liked how the workshops attempted to provide a comprehensive overview of each topic, with Word and Powerpoint use for example, while also allowing time for questions. They felt that “they could ask what they deemed basic questions and not be judged for doing so”. Receiving the notes in advance was very helpful, especially for people who registered but could not subsequently attend. They felt they “did not miss out on a learning opportunity”. In the two months following the workshops, up to the end of the academic semester, the workshop recordings were viewed almost 1,000 times and the LibGuide where the downloadable workshop slides were shared was viewed 2,600 times.

Did you use what you learned in your academic work subsequently?

The goal of the workshops was to enhance student’s digital literacy to benefit their scholarly work. Students cited the EndNote sessions as “particularly useful in helping them to understand how to use this complex tool”. We know from the volume of queries the library receives about referencing in a year, typically 300+ queries, that students find referencing complicated. “Getting this tool (EndNote) set up properly at the early stage of PhD studies is of critical importance” was the view of one of the PhD students. The series included a session on Audacity and participants were shown how to record and edit audio files, which students said “will help them with their own action research in their PhDs”. The Powerpoint and copyright free images sessions were helpful to students in their academic work when preparing presentations, sourcing imagery for inclusion in assignments and understanding Creative Commons licenses. New tools that were not part of academic workflows a year earlier became commonplace in UL in AY 2020/1 e.g., Panopto. Academic staff received training on how to use Panopto from UL’s Learning Technologists Forum, but the students said “this was the first time that this training was offered to students on this scale”. A student who attended the Panopto workshop said that “she found the notes she took during the training helpful for her last assignment in the spring semester”. The Powerpoint for Dummies book which one workshop attendee said she had bought, was “no substitute for the live workshop” about Powerpoint. The workshops introduced participants to features in the tools, like the formatting tool in EndNote. People who attended the poster workshop told us “they are still using Canva, which they had never heard of before the workshop”. The learnings were intended to be for academic purposes, but we heard an anecdote in the focus group that one participant had used what he learned at the Canva workshop to make a card for his wife.

Do you think digital skills should be taught as part of your academic programme?

All students in the focus groups were of the view that all undergraduate students, from the start of their studies should be taught digital skills as part of their course. To quote one focus groupparticipant, “students do a lot of their academic work on Excel and Powerpoint, but they are not taught how to use them properly”. Lecturers refer students to the UL Writing Center when they ask about formatting a document and they largely refer students to the library when they need assistance with academic referencing. In a similar way, lecturers were able to refer students to these workshops to help them build their digital skills. Introducing students to the technologies available to support their academic work might, as we saw with the level of registrations for the 2021 series of digital skills workshops, make students more curious about technology and create some early habits for them to continuously explore the tools that will help them in their studies. The students we discussed this with in the focus group, said a programme of digital skills should evolve and always strive to teach students best practice with technology for learning.

Limitations of this study

This research was conducted during the intensely difficult period of the second year of Covid19. The workshops were delivered in spring 2021 and there was potentially an unnatural demand for digital upskilling on the part of the attendees. It is conceivable that people felt disconnected from campus and realized how much support they needed with their digital skills. It is also worth highlighting that the research does not compare “like with like” as the expanded series offered in 2021 had newer and different workshops to what was offered in 2020 and was delivered entirely online. Both of these factors could account for some of the higher attendance numbers in 2021.

As these digital skills workshops were offered on an extracurricular basis, they were not aligned to the aims and objectives of any academic programme or individual module. They were not assessed for credit and as such it is impossible to determine the long term learning benefit to the participants.

While the reactions gathered in the focus groups were positive, there is always a risk when conducting a focus group that participants will say “what they think the organizers want them to say” (Glitz, Citation1997, p. 388). To try to address that, the focus groups in this study were moderated by an independent convener who attempted to create a relaxed and conversational atmosphere where people felt able to give honest feedback. It is still a concern however.

Future research

Martzoukou (Citation2021) reflects that, based on what we have witnessed during Covid19 “this is a unique opportunity for academic libraries to plan, design, and roll out a sustainable future plan for establishing online education on information skills and digital literacy”. There is an opportunity therefore for libraries to conduct research in to their ability and readiness to actively participate in the provision of more digital skills instruction to students and to plan for this. Whether leading the initiatives or partnering with other campus units to provide digital upskilling, academic libraries are uniquely placed to augment whatever a University might decide to do in the provision of digital literacy instruction. Hallam et al. (Citation2018) assert that there is “great potential for library staff to extend their reach and serve as digital facilitators, connectors and collaborators”, making a significant contribution to outcomes in many areas of contemporary academic life.

Future research might also examine embedding information and digital literacy in to the curriculum within institutions. As a model for this, work is already underway in Edith Cowan University (ECU) in Perth with their Digital Dexterity Framework (ECU, 2020) that outlines the skills and capabilities that students will need to succeed in the workforce. The Center for Learning and Teaching (CLT) and the Library Services Center work together at ECU to embed digital literacy skills into the curriculum.

Discussion

It is fundamental to a student's ability to succeed academically to have an explicit understanding of what is required of them. At the beginning of an academic semester most students will receive course outlines that describe learning outcomes, deliverables, and assessment modes. A stark analogy to illustrate this comes from Coldwell-Neilson (Citation2017, p.79) who says that not telling students what digital skills they require in University is “analogous to having no statements or requirements relating to English language competency for entry into an Australian university”.

The library’s pilot series of digital skills workshops has established that there is a demand for digital skills training among students at the University of Limerick. Students are looking for more digital skills training, and on an even wider range of topics. Regrettably, as this was a pilot programme, we had to turn down requests from lecturers who asked us to deliver the poster making session for a group of students in Week 8 of the spring semester. Similarly, we had to say no when asked to deliver the copyright free images class to postgraduate students in the autumn semester. Time and resources meant that the librarians involved in the project had to turn their attention to other work. The recordings and workshop slides were sent to the lecturers to embed in their teaching but it was disappointing to not be able to meet that need. We could not offer the Introduction to Graphic Design at all in 2021 as the presenter had other work priorities that precluded her from being involved. This pilot series demonstrates that students at UL are interested in building their digital capacity and shows how responsive the University was to begin to address this need. The evidence exists now to inform future planning and potentially open a discussion about integration of information and digital literacy in to the curriculum, as argued for in Johnston’s (Citation2020) article.

The library is a natural place for collaborations to happen (Ard & Ard, Citation2019) and with a pre-Covid annual footfall of over one million people, UL Library’s modernized and high-tech library was a natural space for students to gather and work. New learning spaces planned for the University library include a makerspace, an audio production booth, a VR/AR Experience lab, an innovation hub and a data visualization suite. In providing unique and safe places where students can experiment to learn better practices (Buranen, Citation2009) the university library will be a central player in the provision of both spaces and programmes for student digital upskilling.

Whether extra-curricular or embedded, whether online or in-person, short or long, delivered by faculty or professional staff, this study found that students wanted these digital workshops, as evidenced by their attendance and subsequent feedback. They want to be taught about the topics that were included in the spring 2021 programme, plus several new topics. They want the classes to be made available to them at a time they can easily attend them or receive a recording that they can watch back. They value the expertise of the presenters and from the student perspective, these skills should be taught in academic programmes, at all levels. It is not easy to flick a switch at a university and redesign the curriculum but our experiences with this pilot series can inform curriculum design going forward. The literature reports extensively on efforts to embed information and digital literacy in academic disciplines. Barr, Lord, Flanagan, and Carter (Citation2020) and Salisbury and Sheridan (Citation2011), despite being almost a decade apart, concur on the centrality and necessity of incorporating ILE (information literacy education) across the disciplines. Sheila Corrall’s (Citation2008) review of the literature in this area concludes that of the published strategies she reviewed, “all aimed to embed IL into disciplinary activity, working collaboratively to achieve this”. An up-to-date review of strategies might elicit information about how universities articulate the need for digital literacy to also become embedded in our curricula.

We read in Coldwell Neilson ‘s 2017 study that it is not clear from university websites where the ownership for digital skills lies within universities. It may not be clear who ‘owns’ digital skills but students at UL benefitted from the collaborative approach by three divisions on campus in 2021, united in their commitment to enhancing students digital literacy. Whether led by the library or by another unit on campus, it is clear that resourcing is required in order to sustain this activity and meet the evident student need for digital upskilling.

This study outlined how a collaboration with other professionals in higher education institutions can benefit both libraries and students. We have documented our experiences and made observations about future developments and sustainability of the 2020/2021 approach to digital upskilling of students at University. It is for each library to decide how much of a role it can play in university digital skills provision. With the experiences reported here, it is feasible for academic libraries to have a renewed and positive part to play, as partners or leaders, in the digital transformation that is underway in higher education.

Conclusion

The student voice is a key aspect of this study. Through their participation in the workshops, and their subsequent focus group feedback, it is clear that the students who participated want to be taught how best to interact with digital tools that can help them with their academic work. They’ve told us that they believe digital skills should be embedded in the curriculum. This is an important consideration for universities in curriculum design.

After a pilot series in 2020 the library realized that to scale up an offering of digital skills workshops, collaboration with other divisions would be required. This collaboration yielded benefits to the programme and ensured the series could be delivered, with additional relevant content, for second time. Further collaboration would enhance the series and establish an evidence base around the sustainability of this initiative at the University. One division, in this case, the university library, may have the vision to pilot such initiatives but may not have the capacity to scale the digital upskilling required for a university with 17,000+ students ().

There is a learning in this research for library managers and librarians who teach. As this research found, the attendance rates at library-specific workshops that traditionally might not attract large signups enjoyed a welcome ‘boost’ when offered as part of a digital skills series. In this study, we reported that Searching Library Databases attracted larger numbers when offered as part of a wider skills programme than it did as a standalone offering. This is worth consideration for libraries when planning teaching programmes in the academic year ahead.

Teaching online is, in our experience in particular in this series, different to teaching in a traditional classroom. One vital difference is that having a moderator present with you at a virtual class is beneficial for both teacher and student. We will need to further explore this approach, using a moderator for virtual classes, and conduct more research in to the practicalities and benefits of shorter classes, with two people co-delivering the teaching. For us, there was no additional cost or effort in this, compared to the more usual 1-hour class length where one person would deliver this on their own.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the Directors of the Glucksman Library and the Information Technology Division, and the Head of the Center for Transformative Learning at UL who lent their support to this work by both facilitating and encouraging this collaboration. Sincere thanks to the staff from the library, ITD, CTL and Marcomms who gave generously of their time and expertise to devise, deliver and support this programme of student workshops. Thanks also to our student contributors who led some of the workshops, to the students who attended and were so helpful to us when we needed to conduct our research to understand more about the impact of the workshops. To colleagues who provided invaluable support in this project, our thanks to you also.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Ard, S.E., & Ard, F. (2019). The library and the writing center build a workshop: Exploring the impact of an asynchronous online academic integrity course. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 25(2–4), 218–243. doi:10.1080/13614533.2019.1644356

- Barr, N., Lord, B., Flanagan, B., & Carter, R. (2020). Developing a framework to improve information and digital literacy in a bachelor of paramedic science entry-to-practice program. College & Research Libraries, 81(6), 945–980. doi: 10.5860/crl.81.6.945

- Buranen, L. (2009). A safe place: The role of librarians and writing centers in addressing citation practices and plagiarism. Knowledge Quest, 37(3), 24–33.

- Cardiff University. (2013). Digidol developing digital literacy. http://digidol.cardiff.ac.uk/home/.

- CILIP. (2018). CILIP definition of information literacy 2018. https://infolit.org.uk/ILdefinitionCILIP2018.pdf.

- Coldwell-Neilson, J. (2017). Assumed Digital Literacy Knowledge by Australian Universities: are students informed? Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Nineteenth Australasian Computing Education Conference. Geelong, Victoria. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1145/3013499.3013505

- Corrall, S. (2008). Information literacy strategy development in higher education: An exploratory study. International Journal of Information Management, 28(1), 26–37. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2007.07.002

- Corrall, S., & Jolly, L. (2019). Innovations in learning and teaching in academic libraries: Alignment, collaboration, and the social turn. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 25(2-4), 113–128. doi:10.1080/13614533.2019.1697099

- Department of Communications, Energy and Natural Resources. (2013). Doing more with digital: National digital strategy for Ireland. https://assets.gov.ie/27518/7081cec170e34c39b75cbec799401b82.pdf.

- Department of Further & Higher Education, Research, Innovation and Science (2021). Adult Literacy for Life: A 10-year adult literacy, numeracy and digital literacy strategy. 15607_all_strategy_web.pdf (adultliteracyforlife.ie)

- ECU. (2019). Edith Curtin University (ECU) digital literacy framework. https://www.ecu.edu.au/centres/library-services/teaching-support/digital-literacy-framework.

- Educause. (2021). 2021 Educause Horizon report: Teaching and learning edition. https://library.educause.edu/-/media/files/library/2021/4/2021hrteachinglearning.pdf?la=en&hash=C9DEC12398593F297CC634409DFF4B8C5A60B36E.

- EITCI Institute (European Information Technologies Certification Institute). (2017). Digital skills and jobs coalition. https://eitci.org/digital-skills-and-jobs-coalition.

- European Commission. (2020a). Digital economy and society index (DESI) 2020., Belgium: European Commission. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/desi.

- European Commission (2020b). European skills agenda. Belgium: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1223.

- European Commission. (2021). Digital education action plan (2021 - 2027); resetting education and training for the digital age. Belgium: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/default/files/document-library-docs/deap-communication-sept2020_en.pdf

- Flick, U. (2009). An Introduction to qualitative research: SAGE Publications.

- Glitz, B. (1997). The focus group technique in library research: An introduction. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 85(4), 385–390.

- Glucksman Library. (2021). How to find books in the library collections. Glucksman Library YouTube Channel. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UuEzC1fhxJ0.

- Hallam, G., Thomas, A., & Beach, B. (2018). Creating a connected future through information and digital literacy: Strategic directions at the University of Queensland Library. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 67(1), 42–54. doi:10.1080/24750158.2018.1426365

- JISC. (2015). Building digital capability framework. https://www.jisc.ac.uk/rd/projects/building-digital-capability.

- JISC. (2021). Student digital experience insights survey 2020/21: UK higher education findings. https://repository.jisc.ac.uk/8318/1/DEI-P1-HE-student-briefing-2021-FINAL.pdf.

- JISC. (2020). Student digital experience insights survey 2020: UK higher education survey findings. https://www.jisc.ac.uk/sites/default/files/student-dei-he-report-2020.pdf.

- Johnston, N. (2020). The shift toward digital literacy in Australian University libraries: developing a digital literacy framework. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 69(1), 93–101. doi:10.1080/24750158.2020.1712638

- Martzoukou, K. (2021). Academic libraries in COVID-19: A renewed mission for digital literacy. Library Management, 42(4/5), 266–276. doi:10.1108/LM-09-2020-0131

- McLeod, A., & Torres, L. (2020). Enhancing first year university students' digital skills with the Digital Skill Development (DSD) framework. In D. Schmidt-Crawford (Ed.), Proceeding of society for information technology and teacher education international conference (pp. 373–379). Waynesville, NC: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). https://researchmgt.monash.edu/ws/portalfiles/portal/332253378/329859476.pdf.

- Moghavvemi, S., Sulaiman, A., Ismawati, N., & Nafisa Kasem, J. (2018). Social media as a complementary learning tool for teaching and learning: The case of youtube. The International Journal of Management Education, 16(1), 37–42. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2017.12.001

- National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. (2015). Teaching and learning in Irish higher education: A roadmap for enhancement in a digital world 2015-2017. https://www.teachingandlearning.ie/publication/teaching-and-learning-in-irish-higher-education-a-roadmap-for-enhancement-in-a-digital-world-2015-2017/.

- National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. (2020). Irish National Digital Experience (INDEx) Survey: Findings from students and staff who teach in higher education. https://www.teachingandlearning.ie/publication/irish-national-digital-experience-index-survey-findings-from-students-and-staff-who-teach-in-higher-education/.

- O’Toole, F. (2021, May 29). No one is safe when half of us are digitally illiterate. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/fintan-o-toole-no-one-is-safe-when-half-of-us-are-digitally-illiterate-1.4575846?mode=sample&auth-failed=1&pw-origin=https%3A%2F%2F https://www.irishtimes.com%2Fopinion%2Ffintan-o-toole-no-one-is-safe-when-half-of-us-are-digitally-illiterate-1.4575846.

- Owen, S., Hagel, P., Lingham, B., & Tyson, D. (2016). Digital literacy, discourse: Deakin University Library research and practice. (Report No. 3). Geelong: Deakin University Library. http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30082926.

- QQI. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 modifications to teaching, learning and assessment in Irish further education and training and higher education A QQI evaluation. https://www.qqi.ie/Downloads/The%20Impact%20of%20COVID-19%20Modifications%20to%20Teaching%2C%20Learning%20and%20Assessment%20in%20Irish%20Further%20Education.pdf.

- QS Rankings. (2021). Graduate employability rankings. https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/employability-rankings/2022.

- Salisbury, & Sheridan, L. (2011). Mapping the journey: Developing an information literacy strategy as part of curriculum reform. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 43(3), 185–193. doi:10.1177/0961000611411961

- Secker, J. (2014). Student ambassadors for digital literacy (SADL): final project report. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/59479/1/__lse.ac.uk_storage_LIBRARY_Secondary_libfile_shared_repository_Content_CenterforLearningTechnology_Secker,J_SADLProjectfinalreport_2014.pdf.

- The Open University. (2019). Digital and information literacy framework. https://www.open.ac.uk/libraryservices/subsites/dilframework/.

- Times Higher Education Consultancy. (2021). Digital literacy in the UK: Employer perspectives and the role of higher education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/sites/default/files/digital_literacy_in_the_uk_the_consultancy_report.pdf.

- University of Limerick. (2019). UL@50 strategic plan 2019-2024. https://www.UL/UL_Strategic_Plan_2019-2024_Web.pdf.

- Walton, G. (2016). Digital literacy (DL): Establishing the boundaries and identifying the partners. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 22(1), 1–4. doi:10.1080/13614533.2015.1137466

- Yin, R. (2008). Case study research. London: Sage Publications.

Appendices

Appendix 1:

Workshop evaluation form

Appendix 2:

Focus group questions

Q1. How do you usually learn a new skill, find out how to do something in Word, use referencing software, make a poster etc. like was offered in the programme?

Q2. Why did you sign up for (any one of the workshops)?

Q3. Did it matter to you who was presenting the workshop?

Q4. Did you find the workshop useful?

Q5. Did you use what you learned in the workshop in your academic work?

Q6. Do you think digital skills should be taught as part of your academic programme?

Q7. Is there anything else you would like to say about the workshops?