Abstract

This article details the ‘Decolonisation as Co-Creation’ project, a co-created-with-students approach to decolonisation of a reading list to be used on a specific final year, undergraduate module. This contributes to the overall decolonisation of Aston University through the development of academic outputs and a methodology for approaching the decolonisation of future reading lists. Herein we offer six lessons learned, five outcomes and a four-step process to decolonising a module reading list as carried out by the project participants: library and module leader and student workers. We provide you with our findings only as an example of how the process might work. For us, the most interesting aspect of this process is the unexpected research findings of our student workers; we encourage readers to use the process with an openness to new findings.

Keywords:

There has been expanding interest and progress in student led initiatives related to ‘decolonizing the curriculum’ across the sector and at Aston University, specifically. The wealth of existing literature, conferences and initiatives around librarianship and decolonization have helped Aston University library take deliberate steps in the evolving discussion on how best to support decolonizing the library and the university at large. This is not to suggest that these issues were not already being discussed and addressed within the University beforehand, only that there was a growing need for the library to actively and openly engage with them and to involve students in that process.

Through membership of the Decolonization Working Group, the Library Information Specialist together with the Module Leader for Business Ethics, a final year undergraduate module, initiated an approach to decolonizing a module’s reading list as a component of the larger decolonization process being developed across Aston University. The Library IS and the Module Leader created a framework for (employed) student project participants to explore and co-develop their understanding of decolonization and simultaneously author this paper so as to provide guidance to others interested in decolonizing a module.

As part of the project the student participants were asked to create two written documents: a literature review based around their research and a reflective piece of work on the experience once completed. It is from these documents that the quotations in the paper have been taken and, as co-authors, students were able to confirm the quotes used and where they were to be integrated. In addition, regular meetings were held during the project to input and feedback on how the research was progressing. The Library IS and Module Leader did not write specific reflection reports and so reflective commentary is integrated throughout as part of the narrative. Together, though, the participants/authors were able to develop a co-created approach to decolonization of a reading list and this article.

Herein we offer six lessons learned, five outcomes and a four-step process to decolonizing a module reading list as carried out by the project participants/authors: Library Information Specialist (IS), Module Leader and student workers (recruited from across the university, outside of the module in question). We provide you with our findings only as an example of how the process might work. For us, the most interesting aspect of this process is the unexpected research findings of our student workers; we encourage readers to use the process with an openness to new findings.

In Section “Defining decolonisation” we offer some general background on decolonization as understood by the staff and student authors of this piece. The students’ research and interpretation re-focused how we see and use the term decolonization. This research and analysis were the result of a literature review required of the students (see Section “Working with the students: Library session design and delivery”). In Section “Project impetus and designing the project” we set out the project impetus and our approach to decolonizing a module reading list. For those interested in applying our approach to your modules or in collaboration with students and colleagues, we establish a four-stage process of library session design and delivery. This is set out in Section “Working with the students: Library session design and delivery”. In Section “Application of Library Sessions to the Business Ethics module” we consider what must happen from a module perspective alongside the library-led sessions. Finally, in Section “Outcomes of Decolonization Project”, we reflect on outcomes of our work which may influence how you approach this work for yourself. These are separate to lessons learned (articulated throughout the article) which are more process driven considerations to be seen as touchpoints as you proceed through your own decolonization work.

Defining decolonisation

Co-Creation of a definition

Decolonization, in both theory and practice, raises opposing perspectives due to its broad nature. The Module Leader and Library IS found it important that the members of staff on this project did not define decolonization but rather allowed students to do their research and come to an understanding themselves. Co-creation of our working definition and hence the foundation of our project was hugely important to us. Research suggests that co-creation contributes to the closing of awarding gaps and “improving equality of opportunity” (Universities UK & National Union of Students, Citation2019; University of the Arts London, 2018–2019).

More important for the Library IS and Module Leader, though, was that student workers felt empowered to affect change and influence curriculum and that our efforts to decolonize would benefit from the unique and fresh perspective of students. At Aston 76% of the student population comes from racially diverse backgrounds and 74% of academics come from ‘white’ backgrounds; there is a stark contrast here (Inclusive Aston, Citation2022). Beyond Aston, the educational concern is that majority white teaching staff contributes to longstanding educational reinforcement of power dynamics which privilege (white) European perspectives (Sleeter, Citation2005). Therefore, by co-creating a working definition of decolonization and co-creating the process of decolonizing reading lists, we are able to shift power (in a limited way, at least) away from the white staff participating in this project (the Library IS and Module Leader). This at least breaks the status quo of what is accepted and integrated into pedagogical structures and, at the same time, provides opportunity to our students from non-racialised white backgrounds.

Decolonization

The term "decolonization" was first coined by Moritz Julius Bonn, a German economist, in response to the newly achieved self-governance of former colonies in 1930 (O’Dowd & Heckenberg, R, Citation2020; Wesseling, Citation1987). This process involves challenging colonial narratives and, importantly, is a “responsibility” and a "work that belongs to us all" (Sanchez, Citation2019, p. 8.15). Decolonization is a living project that needs continuous work against the years of damage colonialism and oppression caused (Sanchez, Citation2019). The breath of decolonization calls for wider discourse and reflection as to what it means to "decolonize" and to understand the context of decolonization.

To understand the importance of decolonization, especially in relation to the Business Ethics module, the subject of this Decolonization Project, we must understand that the socio-political situation we are currently in greatly differs from that of the situation in the immediate aftermath of the major post-colonial movements. The world is more interconnected than ever; with the expansion of the internet, information is freely accessible and more available. Due to the convenience of international travel, (especially Western) educational institutions have increasingly become hotpots for people of all nationalities, beliefs, and backgrounds. It is therefore concerning that the standard higher education institutions in the western world still cling to western ideologies and theories.

This creates a call to action: when relating decolonization to the curriculum in western institutions we must understand that the teachings will likely show a narrow perspective of mainly western ideologies and theories, often filled overwhelmingly with a parade of “dead white men” (Buerk, Citation2019). This represents the vocal challenge of accepted knowledge, including the issue of whose voice/authority is given power; forcing certain voice prioritizations onto the next generation otherwise causes a cycle to form, reinforcing a rose-tinted colonial view.

There are those such as Dr Joanna Williams who believe that decolonization is “racist and patronising” (2017). She suggests that the curriculum should be kept under review but that changes should be made based upon merit, not purely for the sake of decolonization. Like many things which challenge the status quo, we agree that mere tokenism is not sufficient and will not appease those who demand change. However, we find it to have merit as a movement, hence our initiative.

For us, this raises several questions: Who decides what changes should be made to the curriculum? Who was allowed to decide the ‘curriculum’ in the first place and why? If the answer to each of these questions continues to be those who have historically held power, then a change must be considered. We must engage with the perspectives of the subjugator and the subjugated so as to get the full picture and not just snippets (Solórzano & Yosso, Citation2002) in order to provide a counter-narrative to the dominating ideology.

Project impetus and designing the project

At Aston University, undergraduate students’ reading habits are formed almost primarily around their online module reading list (Zanella & Akhtaruzzaman, Citation2022, p. 7). Libraries and reading lists remain “key elements in the educational production and reproduction of knowledge and power” (Luke & Kapitzke, Citation1999, p. 467) with reading lists automatically imbuing the assigned texts an unquestioned legitimacy. The repeated inclusion and citation of certain texts consolidates their position in the canon (Crilly et al., Citation2020). Students appreciate their convenience (Marks, Citation2020; Walsby, Citation2020) but few venture further than those texts suggested by their lecturer.

Whilst the impact of lockdown on reading habits has not yet been explored in full, it certainly increased usage of e-texts at Aston University, with module reading lists being the main route of entry for students. Now out of lockdown, a majority of students still want a mix of online and onsite learning (JISC, Citation2022) which will continue to drive demand for e-books and resources.

Since the implementation of an online reading system at Aston University there have been recurrent concerns about whether this amounts to ‘spoon-feeding’ students at the expense of developing students’ critical search skills (Cameron & Siddall, Citation2017; Chad, Citation2018; Stokes & Martin, Citation2008). This, coupled with the possibility that reading lists are likely reflecting the make-up of their academic faculty rather than the student body (Schucan Bird & Pitman, Citation2020) and hence are largely Eurocentric, means that reading lists could be an interesting strand in the larger project of decolonizing.

Creating a libguide

As an Information Specialist it was a relatively simple task to create a libguide page as a central platform to alert students to the variety and depth of critical reading available to them related to decolonization, empowering them in the acquisition of texts (via a supporting reading list and link to an already existent, but little used, book recommendation system). This libguide is continually updated by members of the University’s Decolonization Working Group as they discover new materials in their own disciplines.

Whilst the intentions of the Information Specialist behind the development of this libguide page were well meaning, the lack of clear objectives was apparent. In our ignorance of what decolonization was, the libguide page and project was originally titled ‘Diversify the reading list’ - a vague, non-committal way of taking action which led to immediate confusion between the idea of diversity, inclusion, representation and active decolonization (Adebisi, Citation2019). Diversifying the reading list is not the same as decolonizing the reading list (Begum & Saini, Citation2019). The pages were intended to be a scaffolding for students to use to populate with their own recommendations and resources. However, it was unsurprising that it failed to connect with students when its purpose was unclear.

Lesson learned 1: Make the decolonization of library stocks the clear objective

There was then the realization that the libguide pages were not action in themselves. The creation of a reading list and libguide was insignificant to the process of decolonizing the university, as Kehinde Andrews (Citation2020) notes; “Adding a few more diverse authors to reading lists or offering optional modules in subjects mostly neglected is not action enough”. A tangible change needed to be initiated; to achieve this tangible change we needed to give the students a clear purpose for engaging with their reading list.

A new approach was necessary to allow students to amend and create anew the seemingly static reading lists attached to taught modules. This would suggest a move from a tokenistic library gesture to something that actively engaged with students and helped aid change. This is where the Library + Business Ethics Reading List Project had its genesis.

The initial meeting point between library Information Specialist and academic was due to membership of Aston University’s ‘Decolonizing the University’ working group, formed in 2020, by a group of cross departmental academics and university staff. Membership of this group helped give the initially vague library libguide pages purpose and served as a cross-disciplinary, introductory meeting point between the library, interested academics and other support service staff around the university.

Lesson learned 2: If you want to make a difference, get yourself working across library and discipline silos

The Information Specialist and Module Leader liaised with the university’s student project office to recruit student workers (who were not enrolled on the module in question) to the project. By engaging our student project office, we could identify students who were interested in working on bespoke projects around campus. Additionally, students hired in this way would be paid for their work and were assured that their Placement Year (required of most undergraduates at the University) requirements would be fulfilled, circumventing issues of maintaining engagement with the project. Working with the Student Project Office meant that students would come to the project from a variety of subject areas and cultural backgrounds which would inform the scope and direction of the project. All of this contributed to the overall goal of decolonization in that students were working (not studying and hence part of the teacher/student power dynamic was reduced) and they were free to explore decolonization through their degree discipline or, if they chose, something else that interested them. Varied degree discipline/background meant that the decolonization proposed would be interdisciplinary but intersecting around Business Ethics.

Lesson learned 3: Decolonization work must contribute to improving voice and authority of students, particularly when those students come from varied backgrounds

The IS and Module Leader hosted two pairs of student workers at different stages of their Placement Years. This provided the project with a wider student perspective which came together around the Business Ethics module. It also allowed for practicing and improving the process outlined in Section “Working with the students: Library session design and delivery”.

Working with the students: Library session design and delivery

Once the Project was developed with the Information Specialist and Module Lead, and students were recruited, Library Sessions were developed and coordinated with the Module Lead for impactful integration into decolonization of the module. It was vital to have input from the Module Leader to link back to subject content. This also supported the task of ensuring that students saw the process of decolonization as something wider than a bespoke project, encouraging “them to think of research not as a task of collecting information but instead as a task of constructing meaning” (Simmons, Citation2005, p. 299). Business Ethics served as the topic around which decolonization of reading lists could be done.

Despite the students coming from a wide variety of subject areas (history, politics, computer science and business) none were initially familiar with the term ‘decolonizing the curriculum’. As Charles (Citation2019) notes, they were unaware of the ‘lingua franca’ around the area. Later, discussion revealed that they were intuitively aware of the importance of moving beyond a reading list solely comprised of just ‘pale, male and stale’ authors. Introducing students to the literature around decolonization made them understand that this is a larger movement to which they were now contributing.

The project was divided over two consecutive groups of students, based on their availability. Each group was given a very brief reading list to familiarize themselves with the idea of decolonizing the curriculum. It was purposely brief in order avoid overly influencing the student take on ‘decolonization’ and what it could entail for the project.

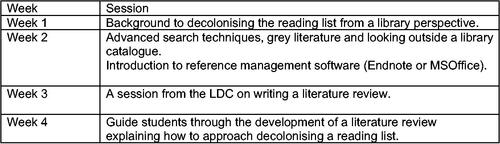

The Library IS decided that to make a literature review part of the methodology of the project. This would be a concrete document allowing the Information Specialist to embed vital literature searching and organizational skills that would then also feed into, and prepare students for, their larger third year research projects. For each cohort of students, a timetable of scheduled library and LDC sessions was created (). These complemented the sessions provided by the Module Leader to provide context on the module reading list under discussion (see Section “Application of Library Sessions to the Business Ethics module”). These were also then bolstered by weekly group meetings to keep track of progress and provide support and guidance. Whilst the amount of guidance and scaffolding needed varied between groups, they did provide a welcome touchpoint for all involved during periods of lockdown.

Students began by defining what the term ‘decolonizing the curriculum’ meant to them. The term ‘decolonizing’ is potentially problematic (Tuck & Yang, Citation2012) so this was an opportunity for the involved students to define their own meaning. Students were encouraged to read around the term and start thinking about how they were going to frame their investigation and literature review. A decision was made (by the Library IS and Module Leader) not to (initially) share each group’s literature reviews lest they unduly influence each other. This meant that each group had a different expectation of what the literature review could comprise.

Students were asked to record the keywords that they used to find information in order help the academic leads understand their definition or perspective of decolonization and what routes they took to get to that information. Exploring student’s search behavior, even such a small snapshot, is always of interest (Griffiths & Brophy, Citation2005; Willson & Given, Citation2014) providing insight into how students approach a research project and utilize the library resources at their disposal.

One of the main benefits of this project from an Information Specialist’s perspective was the chance to imbue information literacy sessions with a sense of purpose and relevancy that they perhaps sometimes lack when embedded into taught modules. At the end of the project, students were asked to write a reflection on their contribution to and the content of the overall project. One student reflected:

“It has been a learning curve for me and hopefully something I can improve on in future work as well as my final year when I do my dissertation as I have used many new search techniques as well as a new software (Endnote) which was really helpful in collating my references until the app expired.”

One student reflected:

“Having never done a literature review before it had definitely opened my eyes after a meeting with… the LDC about how in depth your analysis has to be and something that cannot be talked about just on face value.”

Lesson learned 4: Create a list of skills necessary for engagement with the decolonizing of a reading list from scratch as well as a timetable to achieve that

Student learning was at the heart of this research project, and they clearly learned the value of accessing and utilizing the services of the library in all aspects of their education. As all the students involved were second year undergraduates moving into their final year, it was felt that these sessions would additionally provide them a valuable opportunity to practice necessary information literacy skills and produce a literature review ahead of their final year research projects (in most cases, dissertations) without the pressure of formative marking. It was an opportunity to introduce the idea of critical information literacy to students, allowing them to question and critique sources they were presented with (the reading list in question) and the sources that they found in their own searches.

In general, students struggle with topic engagement beyond surface level. Through the type of outreach provided in this project we see that students can gain skills in critical information literacy. At the same time, this is a vital component of decolonization—finding and engaging with new ideas and critical thinking about those new ideas to challenge the status of quo of their learning.

Application of library sessions to the business ethics module

Whilst the Library activities and planning is the focus of this article, it is important to account for the work being done in parallel by the Module Leader for which this process is being applied. Separate to, but together with, the Library sessions and student-led work, the materials needed to be integrated into the Business Ethics module’s reading list. In this section we offer a brief explanation of that integration as an ongoing process. Additionally in this section, we offer some reflections on decolonizing a reading list as a component, not the embodiment of, decolonizing a module.

First, the literature search findings were integrated into the module reading list. Students made a list of possible texts and the topics those texts might support. The Module Leader went through each suggestion and compared items to the 2020/21 reading list and noted author’s affiliation and topic of content. Despite students’ best effort to find other resources, there is still a priority on Western voices; addressing this is not possible within this article and/or by the authors without buy-in from a much wider group of players. A further outcome of this side-by-side comparison was the realization that ‘capitalism’ needed to be added as a module topic as it would provide the space to discuss inequality and injustice brought about by the global economic system, in which businesses play a huge part.

Due to time constraints of the lecturer, running out of time with the student workers, etc., we are not as far along as we would have wanted—the most recent reading list still very much prioritized white, Western (and male) voices. However, the student + library portion of this project was approached in stages and so small changes could be made from TP1 (Sep–Dec 2021) with our first group of students before the module started again in TP2 (Jan–May 2022).

Student worker suggestions were integrated where possible and relevant. There were many helpful sources offered; most of the suggested texts, though, would have diversified the reading list instead of, more specifically, decolonizing it. This was evident in the fact that traditional power holders—western and white authors, western publishing companies, etc.—constituted a majority of the suggested texts. The Module Leader was specifically looking to decolonize and not diversify. Diversifying the curriculum only speaks to incorporating more voices—it does not engage with and criticize the power structures of our colonial past which have dominated UK Higher Education. Indeed, “Including more modules on race or people of color will not address disparities and discrimination within our institutions” (Lemos, Citation2018). To that end, decolonizing reading lists is a much more nuanced and layered project than it might seem at first glance.

At the same time, decolonizing a reading list is only a small part of addressing the inherent bias and discrimination embedded in learning and teaching in higher education. As Adebisi explains, “we cannot decolonize while relying on colonial logics of commodification of labor and space” (Adebisi, Citation2019). Hence reiterating the same processes that lead to reading list creation, without challenging the very structures upon which libraries and higher education more generally are built, is like using a plaster to heal a broken arm. The Module Leader therefore notes this project’s limited contribution to the decolonization of the module. However, it enhanced her understanding of different perspectives of decolonization which will be applied in future module preparation.

Lesson 5: Decolonizing a reading list is a multifaceted project but forms only a small part of a larger decolonization project to be taken up by the Module Leader with support from the Library

Going forward and where necessary, the Module Leader will first liaise with the Library Information Specialist to see if/how different texts can be purchased either through the decolonization budget and/or budget for the module’s texts. Ongoing attempts at decolonizing the reading list further now fall back to the Module Leader who is looking at the author’s affiliation, topic of case study (or other) in an attempt to ensure it is not US or European-based (Gomez et al., Citation2022; Schucan Bird & Pitman, 2019; Torres and Alburez-Gutierrez, Citation2022). The process of finding further sources, though, will, importantly, consider topics the student workers found relevant and accessible. For example, indigenous voices featured in the student workers’ notes. Also, texts and voices from cultures which may now be considered Western but which have been silenced or weakened by the colonial legacy, i.e. Irish, will be incorporated.

Second, decolonization of the reading list is only one part of decolonizing a module. It is an important part of a decolonial approach to learning and teaching because it is understood to increase a student’s “sense of belonging within the university and so ultimately contribute to the work of closing the awarding gap” (University of the Arts London, 2018–2019). These are ethical and practical reasons for decolonizing reading lists. As we increasingly understand how harmful current ideologies, rooted in today’s education system, can be toward those who do not fall within the racialised-white category, we must take action. It is this realization that originally prompted efforts toward decolonizing the Business Ethics module about three years prior to the start of this project. Shedding our “colonial ideology” and how that “shapes the cruel and often violent racist reality which characterizes our democratic society” (Macedo, 1999, cited in Kharem, Citation2006) is not something that can be achieved through a reading list alone.

As noted above, organizing and enhancing a reading list is only part of developing a module. Hence, this Library project fits within a “decolonial approach” to learning and teaching and “suggests a way of being rather than a destination” (Adebisi, Citation2020). Accordingly, we cannot say that decolonization of Business Ethics has an end state—it is all part of developing, re-developing, managing and delivering a module that should be evolving with time and learning. This is consistent with the Module Leader’s own expectations of and approach to decolonization. The lack of ‘destination’, though, is understandably frustrating to those who embark on similar curricular changes; her suggestion would be to embrace the way of being and recognize that small steps are still steps forward.

Outcomes of decolonization project

In this section we offer reflections and commentary on where we are with this project.

Co-created module reading list – A reading list should be an ever-evolving component of a module. With that, some of the recommendations made through this Project were integrated into the most recent module delivery. However, much work still needs to be done as the reading list does not reflect the extent to which it can be decolonized, even as part of an evolving project.

As the Module Leader is white and an English-only speaker, there is concern around whether the lack of decolonized resources on the module was purely a cultural or language issue (not having access to the cultural understanding or non-English-language texts) or if it was a publication/access issue (our institution does not have library access to an array of texts from non-Western sources). We suspect that the issue rests somewhere between the two. The co-creational aspect of this work was helpful in bringing to light areas the Module Leader would not have considered or focused on (i.e. Irish and Bangladeshi colonial issues). Student research was motivated by personal interest and expectation.

Having students research available texts, though, was reassuring in that it does not seem like there are texts that the Module Leader is simply missing or ignoring that could/should be integrated. However, it does suggest that there is a lack of resources (for the module in question) from Global South voices and perspectives. This is part of a larger, external-to-libraries problem of a lack of diversity and inclusion when it comes to journal leadership and reviewers (Merchant et al., Citation2021).

Going forward, and in order to ensure continued co-creation of a decolonized module, the Module Leader must talk to students about a reading list, including how it can and should be changed. She must be open to student discussion and possible criticism of a module reading list. This openness, though, must also be fostered in/by the students themselves.

Reflections from students for input into how this process worked – As noted in Section “Working with the students: Library session design and delivery”, student workers were asked to reflect on the project via reflective reports, knowing that those reflections may be integrated into the publication as deemed appropriate. Decolonization is not possible without conversation for it is in discussion that existing power dynamics (individual and structural) are challenged (LeGrange, Citation2023). Hence, by asking for reflections the academic members of the team were likewise able to reflect on the value of the project, where problems existed, and what could be changed as the immediate and long-term project of decolonization progressed. For example, students reflected on the wider impact this project had on them:

“It was also important for me as a South Asian person who believes that the curriculum focuses mainly on western views which would make many non-white students vulnerable and exposed in the education system. Upon completing this project, I hope to accomplish moving one step further in decolonising the curriculum across the university.”

“…enabled me to voice my own thoughts and express what I think of the current curriculum and offered me a wider explanation as to why decolonisation is so important in today’s society.”

“I have learnt quite a lot from this project and was happy to take part in it and meet lovely people who were as passionate about the concept of decolonisation as I was.”

As evidenced by student reflections, decolonization has an emancipatory element—that of overcoming and moving beyond the status quo of western education. Indeed, engaging with decolonization in this way has been empowering for the students.

Employability Skills – With critical thinking and soft skills in demand by employers (Desai et al., Citation2016; Pedersen & Hahn, Citation2020; Stewart et al., Citation2016) student employability skills were also built upon with students. At a basic level, critical information literacy skills improved. Additionally, upon completion of the project, students were involved in a podcast and the co-creation of this journal article, adding to their presentation and academic writing skills. As well, this project relied heavily on group work and communication and sought to impress professional and interpersonal skills (organizing team meetings, setting agendas, deadlines etc) on the student workers. All of these soft skills are somewhat difficult to foster in standard educational situations.

This project is also a step toward showing the students involved that their reading lists are not monolithic and that they are able to actively engage academics and university staff in conversation in the creation of these lists. As Elmborg explains, “knowledge is a dialogic that it is negotiated in the discussions, disputes, and disagreements of specialists” (2003, p. 74). With this, the students will be better equipped to enter a particular community of practice (Simmons, Citation2005). As “simultaneous insiders and outsiders in a discipline” (Simmons, Citation2005) subject librarians are well placed to pull back the curtain and allow students to see the processes behind library acquisition and information organization, revealing that information and libraries are not neutral spaces and that critical information literacy skills were vital to both their studies and future careers.

Action Plans for Decolonization are not static - Whilst not without its flaws this project has provided a framework and guidance for the library team to practically approach working with staff and students in decolonizing their reading lists within the University and beyond. It has produced a step-by-step guide for use by Library staff and module leaders to allow a basic structure that will then almost certainly digress according to subject and those involved. Module leaders will have access to findings via the Decolonization group’s network and via wider distribution as possible.

The Action Plan included herein is not static; it should be seen as part of a constant evolution of learning and teaching and part of the decolonization process. Likewise, the lessons learned and reflections, whilst applicable to other educational scenarios, are specific to our experience. We urge readers to take from our experience and develop a ‘decolonizing a reading list’ process that works for you; and then adapt it as necessary.

The Great Divide Between Librarians and Non-Librarians - Student and module leader introduction to the library is key to cross-discipline learning (library + an individual’s discipline). Library classification systems, such as Dewey, are not neutral spaces, reflect historical bias and occlude many lived experiences (Drabinski, Citation2013; Higgins, Citation2016; Olson & Schlegl, Citation2001). This, in addition to counter-intuitive search interfaces mean that library systems are not necessarily conducive to decolonized thought processes that drive student decolonization of a curriculum.

At the same time, fostering ongoing decolonization without library support is unrealistic as students and most staff do not have the knowledge or skills necessary to navigate the library system. This is, in a way, indicative of the problem that decolonization aims to address: academics and students know and explore ‘the canon’; reading and researching beyond that takes particular librarian skills (Simmons, Citation2005) that may not always be present.

Realistically, though, library support is not feasible for every single person in the university, nor does it adequately challenge the power structures. Librarians should look at more ethical resources and can make recommendations about purchasing more open and transparent resources. This type of project draws attention to the structures and power dynamics at play in universities where a select group of, often white, librarians are in a position to decide the texts on offer. For us all to flourish, though, we must seek ‘tools’ that exist outside the status quo structures and systems (Lorde, Citation2017). Indeed, we must find ways to empower students to navigate library systems and, at the same time, challenge their very construction and reinvent the way we engage with text.

Lesson learned 6: Consider alignment more generally: What’s good for a librarian isn’t necessarily good for a module leader

As a first and small step, for example, Aston University’s Library now has an adapted libguide page which serves as a repository for decolonized text. With the imbued legitimacy of reading lists and decolonized texts’ location on a ‘list’, decolonized texts would, hopefully, be seen as the authority. Creating a list also helps academics; those who are unsure of the legitimacy of texts outside of the readings they learned have access to validated sources. That said, there is still a way to go in challenging the way we engage with literature and how that literature is developed in the first place.

Conclusion

In this article we have provided step-by-step guidance and lessons to be heeded by anyone considering working to decolonize a module reading list. This has not been, nor can it be, exhaustive or complete guidance. As the saying goes, ‘circumstances alter cases’. Likewise, and almost more importantly, our guidance cannot be exhaustive because decolonization is a process, not an end goal.

What we have hopefully demonstrated is the value of co-creation, and the importance of engaging across discipline silos when it comes to decolonization. For libraries, our proposed process provides a clear, step-by-step process as, at least, a starting point for cross-discipline engagement.

Finally, we leave you with some thoughts on what one student learned about decolonization and learning more generally as a result of this project:

“The decolonisation project is for everyone. It’s for the people of the past who were told to seal their lips, who were oppressed and had their identity stolen by the hegemonic rulers. This is for the people of the present that are still imprisoned in their past, who are still repressing themselves because of the oppression and are afraid. This project is for the people of the future, for a chance to lead a better journey because someone in the present took a step forward in making a change.”

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adebisi, F. (2019). Why I say ‘decolonisation is impossible’, African Skies, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2023, from https://folukeafrica.com/why-i-say-decolonisation-is-impossible/.

- Adebisi, F. (2020). A Decolonial Approach to Education and the Law (with Foluke Adebisi). Retrieved October 30, 2022, from [Interview].

- Andrews, K. (2020). Blackness, Empire and migration: How Black Studies transforms the curriculum. Area, 52(4), 701–707. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12528

- Begum, N., & Saini, R. (2019). Decolonising the curriculum. Political Studies Review, 17(2), 196–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929918808459

- Buerk, M. (2019). Moral Maze: Decolonising the Curriculum, s.l.: S.n.

- Cameron, C., & Siddall, G. (2017). Opening lines of communication: Book ordering and reading lists, the academics view. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 23(1), 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2016.1224769

- Chad, K. (2018). The rise of library centric reading list systems. HELibTech Briefing Paper, 5. Retrieved from https://helibtech.com/briefing_papers#the_rise_of_library_centric_reading_list_system.

- Charles, E. (2019). Decolonizing the curriculum. Insights the UKSG Journal, 32(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1629/uksg.475

- Crilly, J., Panesar, L., & Suka-Bill, Z. (2020). Co-constructing a Liberated/Decolonised Arts Curriculum. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 17(2). https://doi.org/10.53761/1.17.2.9

- Drabinski, E. (2013). Queering the catalog: Queer theory and the politics of correction. The Library Quarterly, 83(2), 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1086/669547

- Desai, M. S., Berger, B. D., & Higgs, R. (2016). Critical thinking skills for business schoolgraduates as demanded by employers: A strategic perspective and recommendations. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 20(1), 10–22.

- Elmborg, J. K. (2003). Information literacy and writing across the Curriculum: Sharing the vision. Reference Services Review, 31(1), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320310460933

- Gomez, C. J., Herman, A. C., & Parigi, P. (2022). Leading countries in global science increasingly receive more citations than other countries doing similar research. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(7), 919–929. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01351-5

- Griffiths, J. R., &Brophy, P. (2005). Student searching behavior and the web: Use of academic resources and google. Library Trends, 53(4), 539–554.

- Higgins, M. (2016). Totally invisible: Asian American representation in the Dewey Decimal Classification, 1876–1996. Knowledge Organization, 43(8), 609–621. https://doi.org/10.5771/0943-7444-2016-8-609

- Inclusive Aston. (2022). Race equality charter application. Birmingham: Aston University.

- JISC. (2022). Student digital experience insights survey 2021/22: Higher education findings. JISC report. https://www.jisc.ac.uk/reports/student-digital-experience-insights-survey-2021-22-higher-education-findings.

- Kharem, H. (2006). Chapter two: Internal colonialism: White supremacy and education. Counterpoints, 208, 23–47. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42980003

- LeGrange, L. (2023). Decolonisation and anti-racism: Challenges and opportunities for (teacher) education. The Curriculum Journal, 34, 8–21.

- Lemos, S. (2018). Beyond diversifcation: Decolonising history. Social History Society.

- Lorde, A. (2017). Your silence will not protect you. UK: Silver Press.

- Luke, A., Kapitzke, C. (1999). ‘Literacies and libraries: Archives and cybraries’, Pedagogy Culture and Society, 1 January, pp. 467–492. Retrieved February 7, 2023, from https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,url,shib,uid&db=edsbl&AN=RN083750996&site=eds-live.

- Merchant, R., Del Rio, C., & Boulware, L. E. (2021). Structural racism and scientific journals – A teachable moment. JAMA, 326(7), 607–608. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.12105

- Marks, N. (2020). Student engagement in improving access to taught course content at LSE library: Practicalities and pitfalls. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 26(2–4), 403–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2020.1803937

- O’Dowd, M., & Heckenberg, R. (2020). Explainer: What is decolonisation? The Conversation, 22 June.

- Olson, H. A., & Schlegl, R. (2001). Standardization, objectivity, and user focus: A meta-analysis of subject access critiques. Cataloging & Classification Quarterly, 32(2), 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1300/J104v32n02_06

- Pedersen, J., & Hahn, S. (2020). Library instruction versus employers Needs: Do recent graduates have the critical thinking skills and soft skills needed for success? Practical Academic Librarianship, 10(1), 38–53. https://pal-ojs-tamu.tdl.org/pal/article/view/7063

- Sanchez, N. (2019). Decolonization is for everyone. TedxSFU.

- Schucan Bird, K., & Pitman, L. (2020). How diverse is your reading list? Exploring issues of representation and decolonisation in the UK. Higher Education, 79(5), 903–920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00446-9

- Simmons, M. H. (2005). Librarians as disciplinary discourse mediators: Using genre theory to move toward critical information literacy. Libraries & the Academy, 5(3), 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2005.0041

- Sleeter, C. (2005). How White teachers construct race. In C. McCarthy, W. Crichlow, G. Dimitriadis, & N. Dolby (Eds.), Race, identity, and representation in education. Routledge. p. Chapter 16.

- Solórzano, D. G., & Yosso, T. J. (2002). Critical race methodology: Counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780040200800103

- Stewart, C., Wall, A., & Marciniec, S. (2016). Mixed signals: Do college students have the soft skills that employers want? Competition Forum, 14(2), 276–281.

- Stokes, P., & Martin, L. (2008). Reading lists: A study of tutor and student perceptions, expectations and realities. Studies in Higher Education, 33(2), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070801915874

- Torres, A. F. C., & Alburez-Gutierrez, D. (2022). North and South: Naming practices and the hidden dimension of global disparities in knowledge production. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119(10), e2119373119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2119373119

- Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). ‘Decolonization is not a metaphor’, decolonization: Indigeneity. Education & Society, 1(1), 1–40.

- Universities UK & National Union of Students. (2019). Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Student Attainment at UK Universities: #closingthegap., s.l.

- University of the Arts London. (2018–2019). Decolonising reading lists. UAL.

- Walsby, O. (2020). Implementing a reading list strategy at The University of Manchester – determination, collaboration and innovation. Insights, 33(3), 494. https://doi.org/10.1629/uksg.494

- Wesseling, H. (1987). Towards a history of decolonisation. Itinerario, 11(2), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0165115300015473

- Williams, J. (2017). ‘The ‘decolonise the curriculum’ movement re-racialises knowledge’, openDemocracy. Retrieved March 1, 2017, from https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/decolonise-curriculum-movement-re-racialises-knowledge/.

- Willson, R., & Given, L. M. (2014). Student search behaviour in an online public access catalogue: An examination of ‘searching mental models’ and searcher self-concept. Information Research, 19(3) paper 640. Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/19-3/paper640.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6RnKDuYx0).

- Zanella, G., & Akhtaruzzaman, S. (2022). A review of students’ use of textbooks pre and post Covid-19 pandemic. Aston University Library.