Abstract

Reading lists have been described as a stalwart of the academic environment. This article explores the role of reading lists as a pedagogical tool and describes how reading lists contribute to an immersive block teaching model at an Australian university. Little has been written about the application of reading lists in block teaching models. This narrative case study explores how prescribed learning resources and reading lists were reframed as an enabling element of a student-centred, university-wide curriculum renewal project. With a limited number of readings permitted for each unit, a manageable volume of learning was fostered, reducing students’ cognitive load. This article builds on existing knowledge about the use and experience of reading lists in higher education and demonstrates how reading lists contribute to constructively aligned pedagogy in immersive block teaching models.

Introduction

Scholarly literature forms the foundation of academic literacy, the critical synthesis of discipline knowledge and intellectual rigor of higher education. Lists of scholarly information resources have long been used by academics to guide students to the literature seen as essential to their studies (Beard & Dale, Citation2008) and to enable them to start researching the information required to complete their assessments (Siddall, Citation2016). Learning resources and scholarly literature are commonly delivered to students via reading lists aligned or embedded within units of study. This article explores the role of reading lists as a pedagogical tool and describes the way in which reading lists contribute to an immersive block teaching modelFootnote1 implemented at a public, regional Australian university. Reading lists have been an enduring feature of higher education study, even labeled a stalwart of the academic environment (Stokes & Martin, Citation2008). However, little has been written about learning resources and reading lists within the context and application of block teaching models. The case study explores how prescribed learning resources and reading lists were reconceived as an enabling element of an innovative, student-centred, university-wide curriculum renewal project. This article builds on the existing body of knowledge about the use and experience of reading lists in higher education and describes how learning resources accessed via reading lists contribute to constructively aligned pedagogy in immersive block teaching models.

Literature review

Reading lists facilitate access to learning resources recommended by academic teaching staff, to help students acquire knowledge needed for a unit of study. Contemporary higher education curriculum relies on high quality learning resources to engage students, to encourage them to adopt deeper learning approaches (Gledhill et al., Citation2017) and to support students’ academic adjustment to university (Owusu-Agyeman & Mugume, Citation2023). In the Australian higher education context, access to and the quality of learning resources used in teaching is evaluated under the Higher Education Standards Framework in three dimensions—quality, sufficiency, and accessibility (Tertiary Education and Quality Standards Agency, Citation2017). That is, learning resources must be:

Relevant to the expected learning outcomes

Appropriate to the level of study

Authoritative and up to date (Tertiary Education and Quality Standards Agency, Citation2017).

With careful planning and when formally sequenced in curriculum, well-designed and curated learning resources will not only be used by students but will be perceived by them as useful and will contribute to their mastery of the subject (Khogali et al., Citation2011). Horsley et al. (Citation2011) considered learning resources provided in a university course of study as important tools that support student learning and that facilitate student learning through the pedagogic design process.

Typically, a reading list consists of scholarly learning resources in a variety of formats, such as books, chapters, journal articles and multimedia (Chowdhury et al., Citation2023). Reading lists are increasingly delivered online via library managed systems (Marks, Citation2020), such as Talis Aspire or Ex Libris’ Leganto which integrate with learning management systems, such as Blackboard, Canvas or Moodle (Chad, Citation2018). Reading list systems are usually managed by university library staff who use them to track copyright compliance, manage workflows and improve the digital student experience (Chad, Citation2018; Krol, Citation2019; Kumara et al., Citation2023). The cost of administering reading lists has economic implications for both academic and library staff with substantial time spent on the creation, maintenance, and resourcing of reading lists, and library budgets spent on acquiring resources required for reading lists (Croft, Citation2020). While much of the administrative work is facilitated by library staff, the value of reading lists is in their alignment with teaching and learning through the curation work undertaken by academic teaching staff. As such, most research about reading lists has focussed on their use through one of two lens—the student experience or the perspectives of academic teaching staff.

Reading lists as pedagogical tools

Moore (Citation1989) proposed that learning resources, including reading lists, contribute to the learning process through learner-content interaction, which results in changes in the learner’s understanding and perspective. Learning resources included on reading lists are chosen by academic discipline experts to reflect the development of the discipline and define the pedagogic identity of the course designed for the university context (Horsley et al., Citation2011). Brewerton (Citation2014) argued that reading lists play a key role in the learning process and suggested that pedagogic development of reading lists was an ‘underappreciated aspect of the learning and teaching process’ (p. 89). Other researchers have suggested that reading lists are enablers of constructivist alignment and have advocated for reading lists to be constructively aligned with learning outcomes and assessment (Croft, Citation2020; Chowdhury et al., Citation2023). Chad (Citation2018) argued that reading lists support pedagogical scaffolding throughout the student learning journey, while Siddall (Citation2016) identified that reading lists provide an introduction to a discipline, enhance students’ knowledge and their understanding of scholarly research. With the accelerated transformation of online learning that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, reading lists should have increased in importance as tools that facilitate technology-enhanced pedagogy (Chowdhury et al., Citation2023; Croft, Citation2020). However, as there is little research evidence yet to support this proposition, Stokes and Martin’s (Citation2008) assertion that reading lists have been overlooked in the recent evolution of higher education remains relevant.

Student experiences and perceptions

Student and academic views about the use and usefulness of learning resources and readings lists differ. Reading lists have been found to help students understand a subject (Siddall, Citation2016), to stimulate academic reading and help students reach their learning goals (Krol, Citation2019), and as a starting point for assessment tasks (Croft, Citation2020; Siddall & Rose, Citation2014). Students studying at both undergraduate and postgraduate level have described reading lists as their primary source of information for learning resources, activities, and assessment (Marks, Citation2020). From the student perspective, the critical feature of learning resources is their potential to be easily accessible and to provide support in the completion of assessment tasks (Horsley et al., Citation2011). A survey of more than 1000 students at Loughborough University in 2012 found that the most common route to identifying reading material for coursework and assessment requirements was the reading list system (Brewerton, Citation2014). Brewerton (Citation2014) also found that students placed a greater emphasis on the reading lists than many lecturers did, and that students considered many lists were not fit for purpose. A study from the University of Huddersfield found that students view reading lists not as a crutch, but as an important piece of scaffolding which led to further independent information-seeking (McGuinn et al., Citation2017). Students considered that academic reading was a valuable part of studying to help them engage in teaching activities, such as lectures and tutorials, and to reinforce learning and extend understanding (Singer & Bilson, Citation2018). Marks (Citation2020) found that students liked reading lists that were scaffolded to encourage them to read purposefully and critically.

What characterizes a student-centred reading list of learning resources? Three areas of good practice are common among the studies reviewed:

reading lists have a clear purpose and are aligned to learning activities and assessment tasks (East & Sharman, Citation2023; Evenhouse et al., Citation2020);

lists are a manageable length (Horsley et al., Citation2011; McGuinn, et al., Citation2017, Siddall & Rose, Citation2014);

lists are refreshed and kept up to date (Brewerton, Citation2014; Croft, Citation2020; East & Sharman, Citation2023; Marks Citation2020).

Multiple studies found that students expected that readings were directly relevant to the topic of study or an assessment task (Evenhouse et al., Citation2020; Siddall & Rose, Citation2014). ‘They wanted to understand what they had to read, why and when’ (Marks, Citation2020, p. 413). Engineering students at Purdue University reported positive perceptions of learning resources when they were aligned with content and assessment, provided multiple ways to engage with course concepts, were immediately available and were considered trustworthy and relevant (Evenhouse et al., Citation2020). Croft (Citation2020) observed that students invested little or no time in reading list related activities unless they perceived a connection with the assessment task. As well as explicitly linking required readings and learning activities, Siddall (Citation2016) found that lists should not be overly long. Too many readings acted as a barrier as students found themselves overwhelmed and struggled to choose what to read, in what order, and to what depth (Siddall & Rose, Citation2014; Siddall, Citation2016). Students were dissatisfied with long lists as they could not understand what was expected of them, considering two to three readings per week a manageable volume of learning (Marks, Citation2020). Brewerton (Citation2014) also found that outdated lists impacted student satisfaction. Students wanted lists to be regularly maintained with up-to-date resources and latest editions (McGuinn et al., Citation2017). Regular reviewing and refreshing of high quality, relevant and current content motivated students to read (Taylor, Citation2019). However, even when reading lists were static, out-of-date, and inaccurate, students used reading lists to access and retrieve resources that they expected would be relevant to the unit topics (Siddall & Rose, Citation2014). Students welcomed the inclusion of a variety of text and multimedia items in reading lists (Chowdhury et al., Citation2023), as per Martin and Ritzhaupt’s (Citation2023) framework, which recommends using a variety of learning resources, such as texts, web resources, and videos, to help achieve stated course learning outcomes and provide opportunities to engage students through learner-content interaction.

Academic teaching staff experiences and perceptions

In the Australian higher education context, unit coordinators are responsible for selecting, reviewing, and updating learning resources required by students to successfully engage in learning (Horsley et al., Citation2011). Horsley et al. (Citation2011) found that Australian academics selected resources from an historical perspective, incorporating resources that had previously been considered successful in facilitating learning, and discarding resources that had not enabled the achievement of the intended student learning outcomes for the course. Academics surveyed at the University of West London viewed reading lists as beneficial signposts to relevant and specific information for the unit of study (Krol, Citation2019). They saw lists as a means by which to extend students’ knowledge of lecture topics and to help students reach their learning targets. 84% of academics agreed reading lists can be used as a pedagogical tool however only 24% aligned their reading list to assessment tasks (Krol, Citation2019). Stokes and Martin’s (Citation2008) survey of 100 academic staff found that staff sought to prescribe readings for the appropriate learning outcome level and to guide students in the journey from novice to autonomous learner throughout their degree program. Academics agreed that as students progress through their course, they require less guidance and fewer prescribed readings (Krol, Citation2019). As a result, the way in which reading lists are used throughout degree programs may vary; from starting students on their learning journey and introducing them to the research outputs in their subject area, to fostering independent learning and self-directed research (Siddall, Citation2016).

The criteria for choosing reading list items was consistent across multiple studies. Academic staff relied on their own learning, their personal knowledge of authoritative authors and classic texts, access to inspection copies of textbooks, and the availability of resources in the university library (Chowdhury et al., Citation2023; Krol, Citation2019; Stokes & Martin, Citation2008). They also considered their institution’s curriculum design processes and chose learning resources that were appropriate for the level of study, contained current and up-to-date research and practice, and enabled positive student engagement with the subject matter (Chowdhury et al., Citation2023; Horsley et al., Citation2011; Krol, Citation2019; Stokes & Martin, Citation2008). Academics at the University of Northampton admitted they were not good at keeping reading lists up-to-date and only considered updating them once a year (Siddall & Rose, Citation2014). The workload involved in constantly updating learning resources to reflect new knowledge or expectations of the academic discipline also emerged in Horsley et al.’s (Citation2011) interviews with Australian academics. Unsurprisingly, academic staff who left lists static, or updated only if required, did not consider lists a pedagogical tool (Siddall & Rose, Citation2014).

Case study—Immersive block teaching models and reading lists

Immersive block models are curriculum innovations in which students learn over shorter teaching periods and enroll in fewer concurrent units than in traditional semester or trimester models (Goode et al., Citation2023b). Immersive block models have been adopted in universities in Australia, the United Kingdom and North America. Southern Cross University (SCU) implemented an immersive block model, known as the ‘Southern Cross Model’ in 2022 as an innovative academic reset involving curriculum reform across the whole institution (Roche et al., Citation2022). In the Southern Cross Model, students enroll in a maximum of two units per term across six terms each year. The Southern Cross Model is based on three principles of successful university learning:

focused learning in immersive teaching terms of six-weeks

active learning to build student engagement

guided learning using curated content and fostering learner agency while creating learning communities. (Roche et al., Citation2022)

The curriculum implements these principles using media-rich, interactive, and responsive online self-access modules complemented by interactive classes (Roche et al., Citation2022). The implementation of the Southern Cross Model involved wide-ranging curriculum reforms that affected almost all aspects of unit design and delivery including reading lists (Goode et al., Citation2023a).

The Southern Cross Model draws on cognitive load theory which purports that human cognitive processes have a finite capacity constraint which may be overloaded when engaged in complex or multiple tasks, leading to decreases in cognitive performance and potentially poorer academic outcomes (Goode et al., Citation2023a). Reading lists are used by SCU academics to curate focussed, active and guided learning experiences and manage students’ cognitive load. By adopting a curation approach to designing learning experiences, teaching staff carefully and selectively sequence materials and activities that support students to achieve learning outcomes (Roche et al., Citation2022). The guided learning experience is facilitated through interoperability between the Learning Management System (Blackboard) and the reading list system (Talis Aspire) to provide access to readings that have been sequenced by academic staff to scaffold and develop students’ knowledge and skills in alignment with unit learning outcomes. ‘Self-access learning is facilitated through media-rich and interactive online learning modules, affording students the opportunity to progress through learning material at a time and pace that is suitable for each student’ (Nieuwoudt & Stimpson, Citation2021, p. 13). Without this alignment, students may not engage with all the learning activities available because they are not able to integrate the information channeled through various learning resources—they experience cognitive overload (Barile et al., Citation2022). Instead, students may only use a subset of learning resources available, choosing those they find most valuable in learning and motivated by the requirements of assessment tasks (Barile et al., Citation2022).

Reframing reading lists for the Southern Cross Model

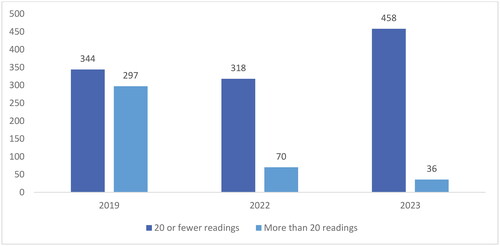

Work to reframe reading lists and prescribed learning resources for the Southern Cross Model began in 2020. University leadership wanted to improve student success and completion rates by addressing the volume of learning and assessment in each unit. Library staff analyzed data from the reading list system to understand the current state and review the number of learning resources assigned to each unit. Using 2019 as a baseline yearFootnote2, the data revealed there were 639 units with reading lists, with an average list length of 23 readings per unit. However, the variation in list length varied greatly. While 54% of units had 20 or fewer readings, 37 units had more than 50 readings (see ). The longest list included 142 readings in a single unit.

Table 1. Number of reading list items per unit in 2019.

The reading list data was presented in mid-2021 to the University’s Academic Standards and Quality Committee whose members made the following recommendations:

The reading list process would be reviewed with a focus on removing system barriers and increasing opportunities for integration with Blackboard to support academics through the unit design process.

Reading lists would normally not exceed 20 prescribed readings (articles/chapters/other) per unit for undergraduate units and 30 readings per unit per postgraduate unit. Additional readings beyond this limit would require Associate Dean (Education) approval.

All readings were to be prescribed, not optional or recommended, aligned with the learning outcomes required for student achievement, and directly related to unit content and assessment activities. Subsequent discussion at the Teaching and Assessment Committee refined the recommendation further with consensus from the Associate Deans (Education) for a limit of 20 prescribed readings per unit, regardless of whether the unit was offered at an undergraduate or postgraduate level of study. Formal endorsement of the reading list items limit was implemented via the addition of clauses to the Assessment, Teaching and Learning Procedure (Southern Cross University, Citation2023). The clauses mandated that prescribed learning resources directly and demonstrably contribute to the achievement of one or more unit learning outcomes, and that prescribed readings such as journal articles, book chapters and other information sources, would not exceed 20 items per unit for undergraduate and postgraduate units. The clauses allowed academic staff to use additional, non-prescribed citations and references in teaching activities when required. The changes to the Procedure provided academic staff with clarity and direction about how readings lists contributed to the volume of student learning and cognitive load in the Southern Cross Model. The clauses also gave Library staff a mandate to ensure that prescribed learning resource lists were of a manageable length and had been reviewed for relevancy and currency. Librarians partnered with academic staff and educational designers to source and curate prescribed resources with an open and digital-first approach aligned with the SCU’s curriculum design principles and the Assessment, Teaching and Learning Procedure. Compliance with the 20 readings limit was monitored and reported quarterly to the Teaching and Assessment Committee. The Southern Cross Model launched in Term 1, 2022 in the degree programs for Science, Engineering, Education, Business and Arts. Law and Health degrees commenced in the block model in Term 1, 2023. shows the immediate impact of the change to the length of reading lists, with the percentage of units with more than 20 prescribed readings dropping from 46% in 2019 to 18% in 2022. In 2023, when all faculties implemented the immersive block teaching model, 36 units (8% of all units using reading lists) had more than 20 readings prescribed. Library staff liaised with unit assessors to document the approved exemptions for units which exceeded the 20 readings cap. Valid exemptions included reasons such as:

Units which were in their last teaching term and would not be offered in the future.

Reading lists which included a variety of resources required to complete assessment tasks.

Multiple image files which were managed through the reading list system to meet copyright compliance requirements.

Discussion

Scholarly information resources made accessible via reading lists play a vital role in the learning process (Brewerton, Citation2014). In immersive block teaching models, reading lists add value as self-directed, guided learning tools facilitating learner-content interaction (Moore, Citation1989). For example, Scott et al. (Citation2018) found that students undertaking an eight-week block course at the University of Sydney made extensive use of learning resources to engage in independent, personalized, self-directed learning. The implementation of the Southern Cross Model required an expansive approach to curriculum renewal, including the way that prescribed learning resources contributed to scaffolded pedagogy, students’ cognitive load and the volume of learning. Defining the maximum number of prescribed readings was an appropriate starting point to reduce cognitive load, prompting academic staff to review, renew, and update lists in line with immersive block teaching principles. ‘The policy changes drove more consistent teaching and assessment practices at the university from 2021 onwards, including a shift to authentic assessment, the more widespread use of open educational resources and a team-based approach to curriculum design and development’ (Wilson et al., Citation2023, p. 14–15). This approach is acknowledged as a compliance-based strategy to influence cultural change. The 20-reading limit was an achievable and realistic target as it reflected existing academic practice with more than half the existing units already prescribing 20 or fewer readings prior to the development of the immersive teaching model. The limit on reading list items aligned with Marks’ (Citation2020) findings that students felt that 2–3 essential readings per week was appropriate and manageable amount alongside assessment and other learning activities. Longer reading lists of learning resources do not necessarily imply that students will complete more reading (Brewerton, Citation2014; Horsley et al., Citation2011) and students are more likely to selectively engage with learning resources to manage their cognitive load (Barile et al., Citation2022).

As well as curbing the length of reading lists to address cognitive load, the redesign and sequencing of prescribed learning resources in a scaffolded manner into modules (Roche et al., Citation2022) increased the relevancy and alignment of lists. Links in each module to learning resources helped students prioritize their reading (McGuinn et al., Citation2017). As a result, reading lists have the potential to become an enabler of constructivist alignment, directly contributing to the unit learning outcomes that describe what the students will be able to do if they successfully complete each module (Croft, Citation2020). The new approach to reading lists at SCU abandoned the concept of assigning readings with ‘essential’ or ‘recommended’ labels (Siddall & Rose, Citation2014). Rather than lengthy lists which included interesting but conceptually irrelevant text and videos (Goode et al., Citation2022) that may have hindered student learning, all readings and learning resources are now considered prescribed or ‘essential’ and are directly aligned to the unit learning outcomes, content and assessment. As modules were redesigned for immersive block teaching, reading lists were reviewed and refreshed, resulting in prescribed learning resources that were of an appropriate length, high quality, relevant and current (Taylor, Citation2019). Early research about students’ experiences of units in the Southern Cross Model indicated that students highlighted the value of relevant and carefully curated learning resources as key to the engagement and enjoyment they derived from online learning modules (Goode et al., Citation2022).

While there is no direct correlation between the changes to reading lists and student success and satisfaction rates, the renewed principles and practices around prescribed readings identify them as one enabling element of the immersive block approach to teaching and learning. Prescribed readings are more carefully constructively aligned to unit learning outcomes, limiting extraneous and distracting content, and scaffolding learning and understanding alongside manageable and authentic assessment tasks (Goode et al., Citation2023b). These changes have also strengthened the curation partnership between librarians, educational designers, and academics who have worked together to carefully and selectively sequence readings, activities and assessments that support students to achieve learning outcomes in efficient and effective ways (Roche et al, Citation2022). As demonstrated in , compliance with the 20-reading limit has been high and has continued into the 2024 academic year. Of the 277 reading lists curated for Terms 1, 2 and 3, only 18 units (6%) have more than 20 resources. The changes in Procedure have empowered Library staff to work with academics to identify contemporary and accessible scholarly resources that align with SCU’s Unit Site Standards. The reduced size of reading lists has made it easier for unit coordinators and Library staff to review and update lists each academic year in alignment with the immersive block teaching principles.

An additional benefit observed by Library staff engaged in curation partnerships, is the increasing awareness and adoption of open education resources and a shift away from a reliance on text-heavy and costly commercial textbooks which do not align well with an immersive block teaching approach. SCU promotes the adoption of Open Educational Resources as the preferred option to commercially published textbooks (Southern Cross University, Citation2023) and the University’s leadership is committed reducing financial and accessibility barriers to engagement by decreasing the number of prescribed textbooks used in units. Since 2019, the number of textbooks prescribed in units has decreased by 45%. Additionally, one zero-textbook-cost degree in the Bachelor of Psychological Science has been implemented and more courses are planned to become textbook free over the next three years, by replacing textbooks with curated reading lists and open educational alternatives (Jurd & Luethi, Citation2024).

Limitations and future research

This case study has described how readings lists can be renewed and repurposed within an immersive teaching model as an enabler of curriculum transformation. The authors attempted to review usage of reading list items over time to measure how students are engaging with reading list content. However retrospective usage data from the baseline year 2019 was not easily accessible from the reading list system to provide a useful comparison. Library staff are working with the system provider to explore future reporting options. Future qualitative research is recommended to understand student and staff experiences of reading lists in the Southern Cross Model. Future research may also include reviewing the types of learning resources prescribed via reading lists to understand what impact the immersive teaching model has on the library’s budget. Preliminary data indicates that usage of video content doubled in 2022 while the usage of e-books decreased during the implementation of the new teaching model. The diversity of learning resources prescribed in reading lists could also be interrogated to ensure that reading lists are representative of the university community, including indigenous voices, gender and ethnic diversity (Schucan Bird & Pitman, Citation2020).

Conclusion

There is immense pedagogic potential in learning resources accessed via reading lists (Taylor, Citation2019). At a time when student expectations of teaching quality are increasing, academic and library staff need to consider whether their reading lists are fit for purpose (Brewerton, Citation2014). The use of learning resources delivered via reading lists in the Southern Cross Model demonstrate best practice characteristics of reading lists design for contemporary higher education. Prescribed learning resources are sequenced and scaffolded in unit modules, relevant, regularly reviewed, and accessible via reading lists (East & Sharman, Citation2023). The redesigned reading list content adds value to the immersive block teaching model through a manageable volume of learning for students throughout the six-week terms. The case study demonstrates how SCU Library staff have been able to leverage reading list data, policy changes and partnerships with academic staff to drive changes that positively impact on volume of learning in the immersive block model. With a limited number of items allowed in each unit’s lists, a manageable volume of learning is enforced, reducing students’ cognitive load. Reading lists are now an enabling element which can contribute toward building students’ focus, critical thinking, and academic success (Goode et al., Citation2022).

Stokes and Martin (Citation2008) argued that pedagogic interventions may be required to make reading lists more valuable. The Southern Cross Model has been that type of intervention—a reinvention that triggered new thinking about the use of prescribed learning resources in an immersive block teaching model. Reading lists are a pedagogical tool within the Southern Cross Model, providing a variety of scholarly resources aligned to unit learning outcomes. The way in which reading lists have been implemented to empower immersive teaching at Southern Cross University has the potential to provide a new approach to the curation and use of learning resources in curriculum design, development, and delivery for contemporary higher education.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge former Southern Cross University staff, Alison Slocombe and Bruce Munro, who led some of the work described in the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The phrase “immersive block teaching model” is used as a term to describe models where students enrol in one or two concurrent units of 5-8 weeks duration as opposed to shorter one-unit-at-a-time models offered over 2-4 weeks (Goode et al., Citation2023b).

2 2019 is used as the baseline year to measure impacts and outcomes associated with the Southern Cross Model to avoid variances attributed to adapted teaching approaches during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021.

References

- Barile, L., Elliott, C., & McCann, M. (2022). Which online learning resources do undergraduate economics students’ value and does their use improve academic attainment? A comparison and revealed preferences from before and during the Covid pandemic. International Review of Economics Education, 41, 100253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iree.2022.100253

- Beard, J., & Dale, P. (2008). Redesigning services for the Net-Gen and beyond: A holistic review of pedagogy, resource, and learning space. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 14(1-2), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614530802518941

- Brewerton, G. (2014). Implications of student and lecturer qualitative views on reading lists: A case study at Loughborough University, UK. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 20(1), 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2013.864688

- Chad, K. (2018). The rise of library centric reading list systems. (Higher Education Library Technology briefing paper No. 5). https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.12337.89445

- Chowdhury, G., Koya, K., & Bugaje, M. (2023). A recommendation-based reading list system prototype for learning and resource management. Journal of Information Science, 49(2), 382–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/01655515211006587

- Croft, D. (2020). Embedding constructive alignment of reading lists in course design. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 52(1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000618804004

- East, M., Sharman, S. (2023). Student perspectives on reading in a digital world. [Paper presentation]. DigiED: Horizons, University of Lincoln, UK. https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1CrwzoYd9y986H15E51Dllmdv5T4zCYYYOV5Kvo2BBFY/edit#slide=id.g15e932021dc_0_619.

- Evenhouse, D., Kandakatla, R., Berger, E., Rhoads, J. F., & DeBoer, J. (2020). Motivators and barriers in undergraduate mechanical engineering students’ use of learning resources. European Journal of Engineering Education, 45(6), 879–899. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2020.1736990

- Gledhill, L., Dale, V. H. M., Powney, S., Gaitskell-Phillips, G. H. L., & Short, N. R. M. (2017). An international survey of veterinary students to assess their use of online learning resources. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 44(4), 692–703. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.0416-085R

- Goode, E., Roche, T., Wilson, E., & McKenzie, J. W. (2023a). Implications of immersive scheduling for student achievement and feedback. Studies in Higher Education, 48(7), 1123–1136. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2184472

- Goode, E., Roche, T., Wilson, E., & McKenzie, J. W. (2023b). Student perceptions of immersive block learning: An exploratory study of student satisfaction in the Southern Cross Model. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 48(2), 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2023.2277419

- Goode, E., Syme, S., & Nieuwoudt, J. E. (2022). The impact of immersive scheduling on student learning and success in an Australian pathways program. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 61(2), 263–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2022.2157304

- Horsley, M., Knight, B., & Huntly, H. (2011). The role of textbooks and other teaching and learning resources in higher education in Australia: Change and continuity in supporting learning. IARTEM e-Journal, 3(2), 43–61. https://doi.org/10.21344/iartem.v3i2.787

- Khogali, S. E. O., Davies, D. A., Donnan, P. T., Gray, A., Harden, R. M., McDonald, J., Pippard, M. J., Pringle, S. D., & Yu, N. (2011). Integration of e-learning resources into a medical school curriculum. Medical Teacher, 33(4), 311–318. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.540270

- Krol, E. (2019, May 13–14). Can online reading lists achieve meaningful engagement with the academics and students within a digital landscape? A case study from the University of West London. [Paper presentation]. 5th International Scientific Conference Information Science in The Age of Change: Digital Revolution - Today and Tomorrow - Infrastructures, Services, Users, Warsaw, Poland. https://repository.uwl.ac.uk/id/eprint/6091.

- Kumara, P. P. N. V., Hinze, A., Vanderschantz, N., & Timpany, C. (2023). Online reading lists: A mixed-method analysis of the academic perspective. International Journal on Digital Libraries, 24(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00799-022-00344-z

- Jurd, M., Luethi, J. (2024). May 6-9). Unlocking knowledge: Promoting Open Educational Resources [Paper presentation]. ALIA National Conference 2024, Adelaide, Australia. https://researchportal.scu.edu.au/esploro/outputs/991013187313702368

- Marks, N. (2020). Student engagement in improving access to taught course content at LSE Library: Practicalities and pitfalls. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 26(2-4), 403–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2020.1803937

- Martin, F., Ritzhaupt, A. (2023). 27/4/23). IDEAS Framework for teaching online. Educause Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2023/4/ideas-framework-for-teaching-online.

- McGuinn, K., Stone, G., Sharman, A., & Davison, E. (2017). Student reading lists: Evaluating the student experience at the University of Huddersfield. The Electronic Library, 35(2), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-12-2015-0252

- Moore, M. G. (1989). Editorial: Three types of interaction. American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923648909526659

- Nieuwoudt, J., & Stimpson, K. (2021). Time for a change: An exploratory study of non-traditional students’ time-use in the Southern Cross Model (Southern Cross University Scholarship of Learning and Teaching Paper No. 2). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3984580

- Owusu-Agyeman, Y., & Mugume, T. (2023). Academic adjustment of first year students and their transition experiences: The moderating effect of social adjustment. Tertiary Education and Management, 29(2), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-023-09120-3

- Roche, T., Wilson, E., & Goode, E. (2022). Why the Southern Cross Model? How one University’s curriculum was transformed (Southern Cross University Scholarship of Learning and Teaching Paper No. 3). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4029237

- Schucan Bird, K., & Pitman, L. (2020). How diverse is your reading list? Exploring issues of representation and decolonisation in the UK. Higher Education, 79(5), 903–920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00446-9

- Scott, K., Morris, A., & Marais, B. (2018). Medical student use of digital learning resources. The Clinical Teacher, 15(1), 29–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12630

- Siddall, G. (2016). University academics’ perceptions of reading list labels. New Library World, 117(7/8), 440–448. https://doi.org/10.1108/NLW-02-2016-0012

- Siddall, G., & Rose, H. (2014). Reading lists – Time for a reality check? An investigation into the use of reading lists as a pedagogical tool to support the development of information skills amongst Foundation Degree students. Library and Information Research, 38(118), 52–73. https://doi.org/10.29173/lirg605

- Singer, H., & Bilson, J. (2018). Assessing the impact on the student experience of embedding information resources in the Guided Learner Journey at the University of Hertfordshire. Ariadne, 78 http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue/78/singer-and-bilson/.

- Southern Cross University. (2023). November 15). Assessment, Teaching and Learning Procedure. https://policies.scu.edu.au/document/view-current.php?id=255.

- Stokes, P., & Martin, L. (2008). Reading lists: A study of tutor and student perceptions, expectations and realities. Studies in Higher Education, 33(2), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070801915874

- Taylor, A. (2019). Engaging academic staff with reading lists. Journal of Information Literacy, 13(2), 222–234. https://doi.org/10.11645/13.2.2660

- Tertiary Education and Quality Standards Agency. (2017, November 22). Guidance note: Staffing, learning resources and education support, Version 1.3. https://www.teqsa.gov.au/sites/default/files/guidance-note-staffing-learning-resources-and-educational-support-v1-3-web.pdf

- Wilson, E., Roche, T., Goode, E., & McKenzie, J. (2023). Creating the conditions for student success: The impact of an immersive block model at an Australian university (Southern Cross University Scholarship of Learning and Teaching Paper No. 10). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4560491