ABSTRACT

While starting as an analogue practice in fanzines, fanfiction in its current form, that is, almost exclusively online, is closely entangled with the technology it is embedded in, both Web 2.0 features and specific website infrastructure. This is nowhere better exemplified than on the platform Archive of Our Own (AO3), which hosts over 13 million stories in thousands of fandoms. AO3 is one of the most popular online repositories for fanfiction and growing exponentially, precisely because of how it deals with this slew of data: its system of extensive hyperlinked labelling. Based on empirical participant data from an online survey and semi-structured interviews, I argue that tags offer distinct affordances and affect user behaviour in such a way that new reading practices arise. Tags create a literacy paradigm interwoven with virtuality, relying on links and networks, and featuring a unique set of characteristics that differentiate reading on AO3 from other digital reading platforms, as well as from print fiction. These include “informed” reading, whereby site users know what they can expect from works, “rhizomatic” reading by navigating across the platform along the metadata, even to unfamiliar fandoms, and reading in multiple, which is facilitated by the site’s searchability.

Introduction: Fan tags

In the wake of new technological possibilities on the internet, literacy research has given much attention to digital narratives using features such as hyperlinks. Technological design strongly influences the user experience and behaviour. Web 2.0 affordances similarly impact how readers interact with digital media as collaborative and continuously growing bodies of content. Research on the use of hyperlinks in digital fiction has, for the most part, focussed on hyperlinks as part of the text itself, rather than in the paratext. Studies tend to be preoccupied with cognitive effects, reader decision making, and reading comprehension which the presence of hyperlinks may have (e.g. Mangen & van der Weel, Citation2017; Pope, Citation2010; Scharinger et al., Citation2015; van der Bom et al., Citation2021). Fanfiction, which is user-generated narrative content based on popular media such as novels, TV shows or games (e.g. Jenkins, Citation1992; Citation2006; Hellekson & Busse, Citation2014; Coppa, Citation2017; Tosenberger, Citation2014), is digital fiction, but not typically seen as hyperlink fiction, since only the paratext contains links.

Digital media scholarship often employs the distinction made in literary studies between text and paratext, as described by Gérard Genette (e.g. Meneghelli, Citation2019), to name the elements of online content. Paratext manages texts’ “relations with the public” (Genette, Citation1997, p. 14) and readers’ “purchase, navigation, and interpretation” (Birke & Christ, Citation2013, p. 68) of a text. While Genette originally only referred to print literature, the concept of paratext, and especially the elements in direct proximity to the text, which he calls the peritext (Genette, Citation1997, p. 344), has been widened to contain other multimodal and digital phenomena (Birke & Christ, Citation2013, p. 65) in recent studies on social media hashtags and the use of tags in fan spaces (Stein, Citation2018). Tags, as peritextual hyperlinks, are an essential feature of many social media, image and video sharing platforms, as well as online marketplaces, and allow users to navigate them efficiently. Labelling content with hashtags ensures that posts are findable (e.g. Lee, Citation2018; Navar-Gill & Stanfill, Citation2018). Some of these websites do not make tags visible, letting them work in the background, and where they are displayed, such as on Instagram, they might not be of interest to many users. Online fandoms are an example of where tags are not only chosen carefully by users, but also displayed and actively read by others for their informational and communicative content. Fan tags have, until recently, been largely overlooked, yet offer much potential to illuminate digital literacy practices and, in the case of fanfiction, evolving aesthetic experiences of digital fiction reading.

Most research on the use of tags by fans stems from Human-Computer-Interaction or Library Information Science research (e.g. Miller, Citation2022). A number of studies analyse fan tags on the blogging platform Tumblr (Bourlai, Citation2018; Hoch, Citation2018; Stein, Citation2018). Tags are also useful for quantitative analyses, as they are easily web-scraped, and can be analysed to observe certain trends across platforms, as Navar-Gill and Stanfill (Citation2018) do. With reference to fanfiction specifically, studies have explored the potential of tags to trace trends in fanfiction (e.g. Messina, Citation2019), tag functions (Gursoy et al., Citation2018), and their importance for findability (Johnson, Citation2014). Lindren Leavenworth (Citation2015) approaches fanfiction paratexts from a narrative theory lens with Genette, highlighting the different uses of fanfiction tags from indicating genres to guiding interpretation and managing reader expectations. Price and Robinson undertake a comparison of tagging practices and functions on the Archive of Our Own, Tumblr and Etsy, finding that fans use tags for various communicative functions beyond describing content (Citation2021). So far, however, no empirical research has considered in depth how the prominent presence and usage of tags may shape the reading experience of fiction that is labelled with such hyperlink paratexts.

David Ciccoricco suggests the useful concept of “network fiction”, which designates narratives in digitally networked environments that make use of hyperlink technology to create connected, recombinant stories (Citation2007, pp. 4–5). In fanfiction, this is achieved by social tagging strategies, which have gained attention with the emergence of Web 2.0 features (e.g. Goh et al., Citation2009; Trant, Citation2009). Systems of “folksonomy” (folk taxonomy) and social tagging are ways to increase a site’s usability, and shape, I argue in the following, the reading experience and reading behaviour. In these systems, users can annotate their own content with keywords or phrases in hyperlinked tags. While fanfiction has a long analogue history reaching back to science fiction fan culture in the 1960s (Coppa, Citation2006), it has become thoroughly intertwined with digital infrastructure since its move online around the turn of the millennium. In its current form, fanfiction is heavily reliant on and shaped by the technology it is embedded in (Busse & Hellekson, Citation2006, p. 13; Stein & Busse, Citation2009). The platform Wattpad, for example, which hosts fanfiction as well as original stories and novels in the public domain, allows readers to comment on each line and read other people’s reactions, revealing the audience’s immediate responses and thus leading to a unique reader experience (Rebora et al., Citation2021). Similarly, I argue, the platform Archive of Our Own creates its own idiosyncratic reading aesthetic due to its feature of extensive social tagging.

This study draws upon empirical data collected as part of a larger project on young fanfiction writers' narratives of engaging with fanfiction. The data corpus contains 245 responses from an online survey and transcripts of 26 semi-structured interviews conducted via videocall and e-mail with fanfiction authors recruited from the same sample. Data collection was undertaken in 2020 and 2021. The sample is controlled for the age bracket of 16–24, but not for specific fandoms or other demographic measures. Participants hailed from 36 countries, with 69% identifying as female, 19% as nonbinary or other, and 6% as male, and around two thirds speaking English as their first language. All participants had written and published at least one fan story on an online platform at the time of recruitment. The survey data was analysed with qualitative content analysis (Mayring, Citation2008), while the interviews were conducted and analysed using a constructivist grounded theory approach (Charmaz, Citation2006). This study has been approved by the Faculty of Philosophy's ethics committee at the University of Zurich. Participants gave written informed consent and did not receive any compensation for their participation.

Archive of Our Own

There are millions of fan-authored stories on the internet, dispersed across numerous platforms, but much more visible, accessible, and easily findable for wide audiences than in their previous analogue form. While analogue fanfiction was mainly dispersed in fanzines of low print runs for dedicated readers and collectors, a few clicks on the internet now allow anyone to browse stories at a previously unimaginable scale. However, this development has also intensified the impermanence of fan stories, which may disappear with archives going defunct, be deleted due to changing platform policies, or taken offline by their creators. Nevertheless, the internet has enormously boosted fan writing and reading as everyday practices. Similar to choosing print books, peritext helps users refine their search and choose specific stories from this vast range. Fans have been described as being selective about the exact content of the fan works they read (Driscoll, Citation2006), making annotations vital to manage the volume of available content. However, fanfiction tags do much more than guide users’ clicks. They are used in strategic ways to communicate different types of information, most of which is not given away in print literature. They serve multiple functions, and feed back into the reading behaviour, which is especially apparent on Archive of Our Own (commonly abbreviated as AO3).

AO3 is a platform founded by the non-profit collective Organisation for Transformative Works consisting of fans, researchers, and professional authors, which also runs the peer-reviewed journal Transformative Works and Cultures and the fandom wiki Fanlore. AO3 was launched in 2008 and has been running in open beta since 2009 (Fiesler et al., Citation2016, p. 2575). Since its inception, it has seen exponential growth to currently over 13 million archived works and 7 million registered users (whereby readers do not need an account to access the works). In their last published statistics, the site operators reported up to 2 billion monthly hits in 2021 (Archive of Our Own, Citation2021). As suggested by its name, AO3 grew out of frustrations with changing policies and content deletion on corporate-owned platforms fans use to share their works, which instigated the development of an archive run by and for fans (Fiesler et al., Citation2016). In contrast to platforms hosting various types of writing besides fanfiction, and other multimodal content, such as LiveJournal, Tumblr, or Wattpad, AO3 was developed with solely fan works in mind (Fiesler et al., Citation2016, pp. 2574–2575). AO3 was declared to be one of the 50 best websites by TIME in 2013, where it was described as “the most carefully curated, sanely organised, easily browsable and searchable nonprofit collection of fan fiction on the Web” (Grossman, Citation2013). In 2019, it won a Hugo Award for “Best Related Work” on behalf of all writers on the platform collectively.

While other platforms featuring fan works have existed for longer, most prominently FanFiction.net, which was founded in 1998, AO3 is currently the most popular fanfiction archive in terms of its growth. Its major attraction is its functionality, specifically its tagging system. More than any other platforms hosting fanfiction, AO3 relies on hypertextual information in tags for organisation and searchability. In the following, I argue that the website’s infrastructure creates a unique reading environment, shaping its users’ reading behaviour in ways that differ from other platforms, as well as from print fiction.

Tagging on AO3

Archive of Our Own was strongly associated with protection from copyright prosecution by study participants due to the platform’s legal advisory team, and receives trust as a safe repository independent of commercial interests. Participants also estimated it to have older user demographics, resulting in higher quality of writing, than other platforms. However, a major part of its popularity lies in the findability of its content. One interview participant called tags on AO3 “a blessing”, while another one jokingly said, “thank god for tags!” Other platforms used to post and read fanfiction restrict tag usage to a few categories, limit their numbers, or supply pre-defined options in dropdown menus. On FanFiction.net, for example, a work can only be tagged with up to four fictional characters and two genres, many of which are traditional literary genres, rather than the genres and tropes fanfiction has established and are frequently used to describe fan-written stories. On the other hand, platforms which are not exclusively designed for fan content, such as Wattpad and Tumblr, allow complete freedom in the tags users can add to a post, meaning that tags only serve their navigational function if used in the exact same way as other users, which relies on users’ voluntary conformism and the absence of typos. In their own way, both types hinder efficient navigation when searching for specific content.

AO3 combines both approaches in a system some scholars call “hybrid” or “curated folksonomy” (Bullard, Citation2016; Goh et al., Citation2009; Johnson, Citation2014). AO3 makes use of a wide range of canonised tags, but involves human interaction by design to manage vocabulary control. To this end, several hundred volunteer moderators work on the platform as “tag wranglers”, ensuring correct spelling and formatting, merging tags referring to the same concept to standardise variations used by different users into new canonical tags, something none of the other mentioned platforms do. Tag wrangling has been described as a form of democratic indexing whereby expert users evaluate and formalise a system’s users’ choices (Price, Citation2019, p. 17). Parallel practices outside of digital fiction exist, for example, in the wiki TV Tropes, which features an abundance of trope hyperlinks in each individual article, managed by its community of contributors.

AO3 provides a detailed guideline for tag usage (Archive of Our Own, Tags, Citationn.d.a; Archive of Our Own, Wrangling Guidelines, Citationn.d.b). To upload a story on the archive, users are prompted to enter tags in a range of different categories: the story’s maturity level (“rating”), content elements related to death, rape, and violence (“archive warnings”), fandoms, relationship types (“category”), characters, an indication of which characters are depicted in what kind of relationship, and “additional tags”. This last category is used to indicate information such as genres, themes, tropes, time and setting, logical relation to the source material, and so on. The first two offer pre-defined options, the others are freeform tag types. Upon starting to type, an autocomplete function suggests canonical tags, helping users to choose tags already in use, but not enforcing their usage. While new tags can be created by users for the freeform categories, using canonical tags is encouraged. If used enough, they are canonised by tag wranglers to appear as auto-complete suggestions. While there may therefore be a number of ways to name a specific fandom or the name of a specific character pairing, tag wranglers manually harmonise them in the background to the same spelling, or connect them as part of a superordinate parent tag, so that users will find all relevant works when searching for any version (Fiesler et al., Citation2016, p. 2575).

This intricate annotation system allows users both to search for and to filter out detailed elements of fan works with high accuracy. The communal effort to keep the archive usable, both from tag wranglers and from writers who select appropriate tags, results in an inclusive, discursively created system, rather than a top-down taxonomy. Indeed, inclusivity was a motivator for the launching team of AO3 to choose this type of tagging system (Fiesler et al., Citation2016, p. 2579). Its strength is also its weakness, as it relies on users employing it in sensible ways. An occurrence in 2021 demonstrated this, when a fan story of several hundred chapters gained attention for adding up to 4400 tags, labelling vast numbers of plot details, character pairings and even unrelated fandoms, which led to the story appearing in many users’ search results. Users complained about it threatening site usability, especially on mobile devices, as it took a considerable amount of time to scroll past the work each time it appeared (Fanlore, Citationn.d.). This inspired a number of memes and copycat posts, including one which featured the entirety of The Great Gatsby broken up into tags (Romano, Citation2021). Whether in direct reaction or not, AO3 introduced an upper tag limit per story of 75 in the same year.

Functions of tags on AO3

Fanfiction tags are integral to readers’ decision of whether to read a story or not. Participants in this study’s dataset described tags as “both a tool of warning and marketing campaign” to attract and inform potentially interested readers. Warnings are meant in the sense of trigger warnings that draw attention to potentially upsetting content, such as violence, mentions of mental health, or character deaths. Such indications are part of the fanfiction ethos and larger fan culture (Wiegmann et al., Citation2023), with writers aware that many community members are minors, sometimes even pre-teen children. Tags are fanfiction’s safety feature, allowing authors to explore mature topics without having to restrict themselves out of concern for readers. With tags, “you can safely warn for anything under the sun”, as one participant said. Participants also reported to attentively read or at least scan the tags before starting to read a story, and to self-censor, especially when they were younger. While AO3, like FanFiction.net, allows registered users from age 13 and up, the vast majority of survey participants reported retrospectively to have started interacting with fanfiction between the ages of 9 and 13. AO3, being the only major English-language pan-fandom platform which does not ban any genres or storyforms, is a space to freely explore any subject a writer may like, with tags adding a prophylactic measure to protect users from potentially upsetting or unsuitable content. AO3’s opt-in and opt-out filtering system thus allows both searching for and avoiding specific content. This resonates with Genette’s definition of paratext as “a threshold […] that offers the world at large the possibility of either stepping inside or turning back” (Genette, Citation1997, p. 2).

The aspect of advertising seems equally important, with numerous participants reporting difficulty to find the right readers on other websites, or expressing a lack of understanding for “undertagged” stories on AO3, as additional tags may increase a story’s reach and appeal. Additionally, many participants thought that anything is allowed in fanfiction, as long as it is correctly tagged. This means that, conversely, if an important element of a story is not tagged, it may upset readers and be abandoned. The general tenet on AO3 seems to be a “live and let live” approach, meaning that users should not leave negative comments on stories regarding elements that were indicated in the tags, but rather filter out features they dislike to curate their own website experience. Readers tend to feel especially irritated by untagged non-canonical character behaviour or drastic changes in plot, as well as untagged sensitive content, such as the death of a main character, as this undermines the opt-out system.

Notably, tags are not exclusively used for classification purposes. The freeform “additional tags” on the AO3 also frequently serve a range of other communicative functions such as personal notes, explanations, metacommentary, affirmations of community membership through memes and in-jokes, conversational snippets, and affective expressions (Gursoy et al., Citation2018; Price & Robinson, Citation2021). Common examples include variations of “I wrote this instead of sleeping”, “this is my first story, please be nice”, “I regret nothing”, directly followed by “I regret everything”, or the meme “no beta, we die like men”, referring to fanfiction’s peer-proofreading system of “beta-reading”. Their tone resembles tags in other fan spaces such as Tumblr (e.g. Kennedy, Citation2024). Bourlai (Citation2018, p. 47) describes fan tags on Tumblr, where there is no vocabulary control through tag wranglers, as an extension of a post’s content, rather than its metadata, and found that conversational tags appeared in fan-related content more than twice as often as in posts from the entire Tumblr community. In addition, comment tags were approximately three times longer on average than keyword tags and were more likely to contain sentiment. It is therefore possible that this convention on Tumblr has influenced tags on AO3, where there is no reason for such expressions in the tags rather than in an author’s note, but has become part of the AO3 user practice.

Fanfiction is a community practice in which readers enjoy getting to know the authors of their reading materials. Many study participants reported to enjoy these commentary tags, because they can be used in creative ways that were perhaps not anticipated when the website was designed. “I think it’s something special about AO3 that I appreciate”, one participant said, “I get so much more of an idea of what a fic is about by these long tags. You get an idea of what the author’s like, even before you click on it”. Gursoy and colleagues argue that fanfiction story tags represent a dialogue with the readership, proposing three rhetorical functions: “identifying”, “reflecting”, and “expressing” (Citation2018, pp. 500–504). Tags can therefore give information on the story itself, show the author’s thought process on the writing, or showcase any other related sentiments. Similarly, Price and Robinson suggest a taxonomy of seven functions, from “descriptive” to “resource”, “ownership”, “opinion”, “self-reference”, “task-organising”, and “play and performance” (Citation2021, p. 325).

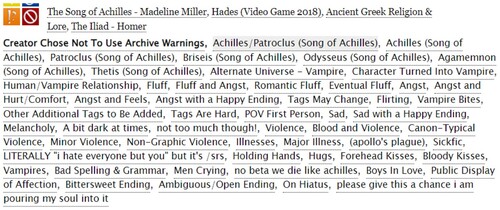

To be able to efficiently apply tags as a fanfiction writer and make sense of them as a reader, users accumulate knowledge of fanfiction-specific tropes, genres, and formats. As an effect, one could argue, fanfiction authors and readers develop a fluency in fanfiction-specific vernacular. Such sociocultural literacy (e.g. Gee, Citation2012, p. 372) is essential to take part in the community, as fanfiction tropes and genres do not map neatly onto categorisations used in media scholarship or commercial marketing, instead following their own logic and conventions (e.g. Coppa, Citation2017, p. 9) (). Fanfiction tropes and genres might include new conceptions like the genre “fluff”, the setting “Omegaverse AU”, meta-commentary like “fix it”, or other content tropes like “de-aged character” and “Mpreg”. Formats might seem equally quizzical to the uninitiated, such as “chatfic”, “drabble”, or “5 + 1”. Slight differences can influence the meaning of a tag: romantic relationships between characters are indicated with a slash between character names, while the ampersand indicates a platonic relationship featured in the fan story. The tag “dead dove, do not eat”, which is based on an online meme, expresses that the story will serve exactly what the tags say, often in reference to violence or gore. Such pointers are exceedingly untransparent to outsiders, but important to understand for users of AO3.

A new reading paradigm?

The tags shown in fanfiction stories’ paratexts, along with the story summary and further information such as the chapter count, are on readers’ minds before they start reading. The hyperlinked tags are also navigated along to find similar content. A study found that readers think interesting fanfiction is easier to find than compelling print fiction, as fanfiction provides more information before consumers make the decision to read (Miller, Citation2022, § 6.1). Comparing search strategies, Miller also found that searching for books in libraries, book shops, or even e-books in online stores, is often undirected—in other words, readers tend to browse. For fanfiction, on the other hand, readers in her study utilised more directed searching to find and choose reading materials, focusing more on specific aspects of the texts they want to read (§ 5.1). In the following, I argue that this creates a reading experience and reading behaviour specific to online fanfiction, perhaps specific to AO3, due to its particularly elaborate tagging system.

Informed reading

Tags reveal much about what a reader can expect from a story—spoilers, as they would be called in commercial media. Yet, what seems like a flaw is an essential feature of fanfiction. Fans have aptly been described as looking for both “more of” and “more from” a source text (Pugh, Citation2005, p. 19). However, they seek not just any fan material, but often follow niche interests among the countless available stories and therefore want to know in advance what they can expect from a fan work. When entering fan spaces, they often arrive knowing what they are looking for, using the tags to navigate to what they have in mind, provided that someone has written it. This may be a specific scenario or trope, or a story element they found intriguing or unsatisfactory in the source text, such as an unexplained backstory or a character relationship that was not realised. Sometimes, it is a tag they like independent of the fandom, meaning that they will look for fan stories with that particular tag in any fandom.

As important elements of each fan story can be expected to be tagged, fanfiction readers are generally tolerant of how other fans reinterpret the source material. Tags make it easy for readers not to engage with elements they might not enjoy. To prevent spoilers, writers may choose the tag “author chose not to use archive warnings”. This tag can be selected in the category “archive warnings” and gives writers the option to hide plot twists without upsetting readers, signalling to “read at your own risk” (Fiesler et al., Citation2016, p. 2583). Alternatively, some writers update the story tags as new chapters are added, so that spoiler-worthy tag only appear when the affected chapter is posted. In this case, many authors still highlight in their author’s notes that the tags have been updated to warn readers. Tags can therefore be work in progress, just like the often episodic fan stories themselves (Busse, Citation2017, pp. 114, 118). A third way to manage spoilers is for writers to hand agency to their readership by putting content warnings into the endnotes, which appear at the bottom of a chapter, and to refer to them in the author’s note at the beginning, so that readers who have no content preferences can avoid exposing themselves to the information. Other peritext that is not the focus here, such as the author’s notes, may therefore also have a priming effect (Meneghelli, Citation2019, pp. 182–185).

That being said, foreknowledge about a story’s outcome may in fact not spoil readers’ enjoyment, but enhance it and create anticipation, Meneghelli suggests (p. 177). Moreover, it is certain institutionalised information that is provided, whereas in print fiction, indications of content are typically given in more vague terms to raise readers' interest (p. 177). While Meneghelli cautions that not all real readers might wish to be informed about a story's content, but indeed have little choice (pp. 177–178), my data indicate no negative feelings about the forewarning nature of fanfiction tags. In fact, as pointed out, they are what draws readers to AO3 and irks them about other sites. One participant said:

I started on AO3, and I very much understand the culture of that, and then moving to FanFiction.net, where the summaries are shorter, and you know much less what a fanfiction is about before you go into it, this changes your relationship to how you look for fanfiction, and how you present your own fanfiction.

I don’t really read romance books IRL because I find [them] incredibly annoying. Why would I read about two random people in a predictable scenario when I could read about characters I already like in this scenario? With fanfiction, I can read about characters that I like in situations that I think would be interesting or cute, so I appreciate tags. In real books, I want something original that makes me care about the characters. Also, fanfic is free. I'm not going to pay for a book if I already know what’s inside.

Rhizomatic reading

Another implication of tags comes through their hypertextual function: once a fanfiction reader has established which types of stories they enjoy the most, tags make it easy to navigate to more of the same, and even across fandoms. This practice of filtering by a specific tag to find more stories is sometimes called “reading a tag” in the fanfiction community. One participant reported that she found almost all the fandoms she engages with “by scrolling through specific additional tags and finding that even if I didn't know the fandoms, the contents of the fic jived with me”. This leads to situations where some fanfiction readers indeed read fan works of source texts they have never read or watched, piecing them together from fan content and completely circumventing the commercial source texts. “The fanfic is usually more interesting in my opinion”, the same participant explained, “and I get all the context I need from the fics tagged ‘Canon Compliant’ or by inferring canon events through the characters’ interactions”. This occurs often in crossovers, where readers may be familiar with one of the fandoms, but not the other combined in the same story. While some participants in these cases were motivated by fan stories to retrospectively consume the source media, more were satisfied with reading the fan works only. Another participant was interested in stories related to intelligence agencies and reported moving along this tag across various fandoms, leaving familiar source texts behind. Similarly, numerous participants mentioned reading stories in fandoms they were unfamiliar with because they followed their favourite fan authors, whose usernames are also hyperlinks on the archive, to new fandoms. This browsing behaviour resembles common, though under-described practices on large non-fandom databases that use social tagging, such as the International Movie Database (IMDb), on which users can browse from entry to entry along hyperlinked keywords. Navigating fan stories in such a way surfaces commonalities between stories and caters to reading interests beyond the level of the individual story by delivering elements of “aboutness”, rather than perceived spoilers.

In a large-scale, non-academic survey about fanfiction readers’ relationship to source texts run on their blog and podcast Fansplaining, Elizabeth Minkel and Flourish Klink similarly found that tags are so vital as navigational tools to some fanfiction readers that they pay more attention to them than to the source texts the fan works transform (Citation2021). While fan scholarship generally takes fannish passion for granted in fanfiction spaces, the affective connection of a fanfiction reader to a specific source text can therefore be tenuous; readers might only interact with it because of a favourite author or content trope. The inspiration for Minkel and Klink’s survey was a letter from a listener, who called this “doing fandom backwards”, as she tends to navigate fanfiction via additional tags, rather than via fandoms or characters, often before or never engaging with the source texts themselves. “When I pull up AO3 to find a new fic”, the podcast listener wrote, “my motivation is hardly ever 'I want to read a Drarry [Draco/Harry] fic' or 'I’m in the mood for some 1D [One Direction] today'. It’s more, 'I could really go for a fake dating AU [alternate universe]' or 'I need a cathartic hurt/comfort scene with found family, please and thank you'” (Minkel & Klink, Citation2021, n. p.). The AO3 is the only major fanfiction platform that is so thoroughly hyperlinked that it allows for such easy cross-fandom search via any tag category. Migratory users navigate along the tag “roads” as some fandoms offer more content featuring certain storyforms than others.

Minkel and Klink’s survey further found that of 6744 participants, only 16% never read fanfiction of source texts they are not fans of, and only 25% never read fanfiction they have not consumed the source text for. This is even more pertinent than in my comparatively small interview dataset of 26 participants, in which these behaviours were reported only by a minority of one in four participants. Part of the disparity may stem from the fact that I did not, like Minkel and Klink, provide nuances: in their survey, participants selected that they are often “somewhat familiar” with a source text, either by seeing other fans talk about it, receiving recommendations, reading summaries or even having consumed a part of it. Only 8% said they would read a fan work without ever having heard of the source text, therefore meaning that most had already had some kind of contact with new source texts, even if this does not mean full consumption. On the other hand, only 13% said that they need to have consumed all of it (Citation2021, n. p.). This points at a sizable spectrum in between.

To break down notions of hierarchy and ownership, Abigail Derecho frames fanfiction as “archontic literature”, based on Derrida’s notion of the archive (Citation2006). Such literature, Derecho argues, accumulates horizontally around a specific text, rather than hierarchically. In a similar vein, Anne Jamison ascribes a rhizomatic nature to fanfiction, borrowing from Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the rhizome as postmodern, non-hierarchical and non-linear networks resonant with how fanfiction tropes and storyforms spread, repeat, abandon certain strands and appear again elsewhere (Citation2018, p. 534). No central authority policies or guides the emergence and popularisation of fanfiction tags; they are developed in discourse, read by interested audiences, and reproduced again by audience members who are themselves writers in new fandoms and produce new recombinations; “it’s a cyclical thing”, one participant said. Just as its writing, I argue that fanfiction reading on AO3 is also rhizomatic, with metadata serving as the connection between the several million stories, along which readers navigate their way across the site, engaging with a wide range of stories they may not have otherwise encountered.

Reading in multiple

Fanfiction reading encourages reading in multiple and in parallel. The serialised format of most fan works, with the exception of “one shots”, are uploaded in multiple chapters, often with waiting periods in between publication. This waiting period can be long, with some stories taking years to be finished, and fan works are also, in contrast to most commercial book series that require similar shared waiting periods from the readership, frequently discontinued without warning or explanation. Therefore, a reader enters the reading of an unfinished story with specific expectations of potentially having to wait for a long time, or never being able to learn the outcome of the story. This, of course, is only possible in the absence of a requirement for fanfiction to be marketable and make monetary profit. Due to such waiting periods, and in connection with the aforementioned “rhizomatic” ways of finding similar stories, it is not uncommon for fans to read many similar works in parallel, either in the same fandom, or featuring similar tags. Popular memes are shared about the high number of fanfiction stories readers bookmark for later, which they may or may not find time for (). As fanfiction is based on a gift economy, fan works are liberally clicked on, saved, and abandoned again.

The AO3 infrastructure facilitates reading many similar works via the tags, and many works simultaneously while waiting for updates via the option to subscribe to a story and receive update notifications. Such non-traditional reading behaviours are often questioned when readers are children or adolescents, and with a large portion of users interacting with fanfiction thought to be young people (Silberstein-Bamford, Citation2023, p. 146), this is informative to youth literacy studies. In their article dedicated to dispel misconceptions about how young people read, Shirley Heath and Jennifer Wolf point out that, while repeat-reading may seem limiting or detrimental to adults, young readers in reality connect it to forging affective relationships and deep reading of specific characters or plots (Citation2012, p. 151). While Heath and Wolf’s arguments refer to print books, similar repeat-reading behaviours are fostered and often intensified in networked fiction that is findable along hyperlinks.

Serial effects in fanfiction reading are created by multi-chaptered, unpredictably updating stories, by parallel and close consecutive reading of large numbers of stories, and by repeat-reading of similar themes and tropes. Fanfiction is viewed as a polyvocal interpretive space in which no story has superiority over another (Busse & Hellekson, Citation2006, p. 8). Neither do they have to be consumed in any particular sequence or according to any specific logic. This is evocative of the increasing trend towards transmedia storytelling with multiple entryways, but in contrast also produces inconsistencies and alternate versions (Kustritz, Citation2014, pp. 229–230). However, in order to understand the flow of tropes and genres in the larger fanfiction community, serial reading is helpful. As Coppa remarks (Geraghty et al., Citation2022, p. 5), fanfiction is best viewed as an ecosystem,

because it’s difficult to impossible to read a single piece of fanfiction in isolation; fanfiction is a networked thing best read in batches which inform and explicate it so as to form something more than the sum of its parts.

Conclusion

On Archive of Our Own, fanfiction becomes a mode of storytelling able to cater to very specific requirements thanks to its hypertextual metadata. Fans use various categories of tags to navigate through the maze of stories to find the ones meeting their exact tastes and desires, sometimes filtering out what they do not wish to see. Rather than undirected browsing, readers tend to search for specific content. AO3 effectively delivers “literature on demand” through the website functionality, which allows easy navigation through millions of works and affords informed, forewarned reading. The prioritisation of predictable wish-fulfilment over surprise is understood as diverging from commercial fiction by platform users: the tonal and structural “spoilers” communicated through tags consciously contrast the approach of more conservative “teasing” taken by professional publishers. Users can also move within a fandom or across fandoms by following tags, making AO3 a unique ecosystem of highly interconnected reading. In what I called “rhizomatic” reading, fanfiction readers are able to follow any of the hyperlinked peritext across the whole platform, something not possible on platforms with more limited hyperlink categorisations. This means that readers may, and in fact do, interact with many source texts not primarily as fans, but rather with an interest in a specific author, trope, setting, or story format. Fanfiction reading behaviour is therefore likely less governed by affective fandom and more by the appeal of the fan works themselves than previously assumed in fan studies. Finally, reading in sequence, in parallel, and in multiple are common ways of consuming fanfiction due to uploading and structural patterns, which in turn encourage to fill waiting periods with more similar texts found via directed searching. All in all, fanfiction reflects the technology it is represented in, an idea stretching back to McLuhan (Citation1964), in whose theory fanfiction is a medium with a message: stories can be enjoyably told and consumed through sprawling, intertextual, participatory networks.

The technological environment of hyperlinked fanfiction affects reader behaviour in a way fiction in other materialities does not. This means that removing fanfiction from its networked environment and treating it as standalone text, for example by printing it out, or by incorporating it into institutionalised spheres like literary awards or classroom teaching, erases meanings and context (Dietz, Citation2023; Busse, Citation2017, pp. 146–147; Raw, Citation2020, §. 2.1). However, reading a wide variety of fanfiction may offer pedagogical potential by teaching trope literacy: multiple participants reported to have learnt primarily through fanfiction what narrative tropes are, as they are overtly labelled (see also Silberstein-Bamford, Citation2023, pp. 155–157). Recognising repeating scenarios and constellations allows young readers to become aware of intertextuality and understand fiction as constructed fantasy, rather than mirrors of reality. Fanfiction is an ideal space of learning this distinction, as it has a tendency to explore topics of distressing nature often deemed unsuitable for the commercial market. This study's participants overwhelmingly reported to have an interest in fan stories featuring moral ambiguity and dark themes not present in the source texts, but added and carefully tagged by fan writers, allowing young readers to explore such themes while being in control of exactly what content is filtered in and out. However, efficient use of the technological environment fanfiction operates in can only be accessed by the initiated. A specific literacy to correctly use and interpret the tags is necessary, as they often diverge from categories used in commercial marketing. As tags evolve without the control of an institutional authority, some are only intelligible to the fanfiction community and difficult to make sense of without background knowledge, although recently, there is some overspill into the commercial sphere, with publishers using fandom-originating trope tags, such as “enemies to lovers”, in their Young Adult segment marketing. While this trope undisputably appears in many commercial books, it is online fan spaces which have named the trope and popularised the term. It should be intriguing to observe future effects of such a trope-literate young fiction readership.

Acknowledgment

We thank the reviewers for their exceptionally helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Archive of Our Own. (n.d.a). Tags. https://archiveofourown.org/faq/tags?language_id = en

- Archive of Our Own. (2021). AO3 News: AO3 Traffic. Tumblr. https://ao3org.tumblr.com/post/673074152446590976/images-daily-ao3-traffic-in-millions-of-page

- Archive or Our Own. (n.d.b). Wrangling guidelines. https://archiveofourown.org/wrangling_guidelines

- Birke, D., & Christ, B. (2013). Paratext and digitised narrative: Mapping the field. Narrative, 21(1), 65–87. https://doi.org/10.1353/nar.2013.0003

- Bourlai, E. E. (2018). ‘Comments in tags, please!’: Tagging practices on Tumblr. Discourse, Context & Media, 22, 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2017.08.003

- Bullard, J.. (2016). Motivating invisible contributions. GROUP ‘16: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM International Conference on Supporting Group Work (pp. 181–193). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2957276.2957295

- Busse, K. (2017). Framing fan fiction. Literary and social practices in fan fiction communities. University of Iowa Press.

- Busse, K., & Hellekson, K. (2006). Introduction: Work in progress. In K. Hellekson & K. Busse (Eds.), Fan fiction and fan communities in the age of the internet: New essays (pp. 5–32). McFarland.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

- Ciccoricco, D. (2007). Reading network fiction. University of Alabama Press.

- Coppa, F. (2006). A brief history of media fandom. In K. Hellekson & K. Busse (Eds.), Fan fiction and fan communities in the age of the internet (pp. 41–59). McFarland.

- Coppa, F. (2017). The fanfiction reader. Folk tales for the digital age. University of Michigan Press.

- Derecho, A. (2006). Archontic literature. A definition, a history, and several theories of Fan fiction. In K. Hellekson & K. Busse (Eds.), Fan fiction and fan communities in the age of the internet: New essays (pp. 61–78). McFarland.

- Dietz, L. (2023). Showing the scars. Proceedings of the 34th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media, (September 2023), Article 21. https://doi.org/10.1145/3603163.3609056

- Driscoll, C. (2006). One true pairing: The romance of pornography and the pornography of romance. In K. Hellekson & K. Busse (Eds.), Fan fiction and fan communities in the age of the internet (pp. 79–96). McFarland.

- Fanlore. (n.d.). Sexy times with Wangxian. https://fanlore.org/wiki/Sexy_times_with_Wangxian

- Fiesler, C., Morrison, S., & Bruckman, A. (2016). An archive of their own. HCI and Gender: Chi, 2574–2585. https://doi.org/10.1145/2858036.2858409

- Gee, J. P. (2012). Discourse and “the new literacy studies.” In J. P. Gee & M. Handford (Eds.), The Routledge handbook in discourse analysis (pp. 371–382). Routledge.

- Genette, G. (1997). Paratexts: Thresholds of interpretation. Cambridge University Press.

- Geraghty, L., Chin, B., Morimoto, L., Jones, B., Busse, K., Coppa, F., Santos, K. M., & Stein, L. E. (2022). Roundtable: The past, present and future of fan fiction. Humanities, 11(120), 120–111. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11050120

- Goh, D. L., Chua, A., Lee, C. S., & Razikin, K. (2009). Resource discovery through social tagging: A classification and content analytic approach. Online Information Review, 33(3), 568–583. https://doi.org/10.1108/14684520910969961

- Grossman, L. (2013, May 1). Archive of our own. TIME. https://techland.time.com/2013/05/06/50-best-websites-2013/slide/archive-of-our-own/

- Gursoy, A., Wickett, K., & Feinberg, M. (2018). Understanding tag functions in a moderated, user-generated metadata ecosystem. Journal of Documentation, 74(3), 490–508. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-09-2017-0134

- Heath, S. B., & Wolf, J. L. (2012). Brain and behaviour: The coherence of teenage responses to young adult literature. In M. Hilton & M. Nikolajeva (Eds.), Contemporary adolescent literature and culture: The emergent adult (pp. 139–154). Ashgate.

- Hellekson, K., & Busse, K., Eds. (2014). The fan faction studies reader. University of Iowa Press.

- Hoch, I. N. (2018). Content, conduct, and apologies in tumblr fandom tags. Transformative Works and Cultures, 27. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2018.1198

- Jamison, A. (2018). Kant/squid (The fanfiction assemblage). In P. Booth (Ed.), A companion to media fandom and fan studies (pp. 521–538). Wiley Blackwell.

- Jenkins, H. (1992). Textual poachers. Television fans & participatory culture. Routledge.

- Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture. Where old and new media collide. New York University Press.

- Johnson, S. F. (2014). Fan fiction metadata creation and utilisation within fan fiction archives: Three primary models. Transformative Works and Cultures, 17. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2014.0578

- Kennedy, K. (2024). "It's not your Tumblr": Commentary-style tagging practices in fandom communities. Transformative Works and Cultures, 42. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2024.2475

- Kraxenberger, M., & Lauer, G. (2022). Wreading on online literature platforms. Written Communication, 39(3), 462–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/07410883221092730

- Kustritz, A. (2014). Seriality and transmediality in the fan multiverse: Flexible and multiple narrative structures in fan fiction, art, and vids. TV/Series, 6, 225–261. https://doi.org/10.4000/tvseries.331

- Lee, C. (2018). Introduction: Discourse of social tagging. Discourse, Context & Media, 22, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2018.03.001

- Lindren Leavenworth, M. (2015). The paratext of fan fiction. Narrative, 23(1), 40–60. https://doi.org/10.1353/nar.2015.0004

- Mangen, A., & van der Weel, A. (2017). Why don’t we read hypertext novels? Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies, 23(2), 166–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856515586042.

- Mayring, P. (2008). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken.

- McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media. The extensions of man. McGraw-Hill.

- Meneghelli, D. (2019). Around the metadata wall. Some functions and effects of paratext in fan fiction. Interférences littéraires/Literaire interferenties, 23, 171–185.

- Messina, C. M. (2019). Tracing fan uptakes: Tagging, language, and ideological practices in The Legend of Korra fanfictions. The Journal of Writing Analytics, 3(1), 151–182. https://doi.org/10.37514/JWA-J.2019.3.1.08

- Miller, N. J. (2022). Information-seeking behaviors of young adult readers of fiction and fan fiction. Transformative Works and Cultures, 37. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2022.2245

- Minkel, E., & Klink, F. (2021, March 21). The fic and the source material. Fansplaining: The Podcast By, For, and About Fandom. https://www.fansplaining.com/articles/the-fic-and-the-source-material

- Navar-Gill, A., & Stanfill, M. (2018). “We shouldn’t have to trend to make you listen”: Queer fan hashtag campaigns as production interventions. Journal of Film and Video, 70(3-4), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.5406/jfilmvideo.70.3-4.0085

- Pope, J. (2010). Where do we go from here? Readers' responses to interactive fiction. Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies, 16(1), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856509348774.

- Price, L. (2019, July 15–16). Fandom, folksonomies and creativity: The case of the Archive of Our Own. In David Haynes & Judi Vernau (Eds.), The Human Position in an Artificial World: Creativity, Ethics and AI in Knowledge Organization. ISKO UK Sixth Biennial Conference, London (pp. 11–37). Ergon Verlag.

- Price, L., & Robinson, L. (2021). Tag analysis as a tool for investigating information behaviour: Comparing fan-tagging on Tumblr, Archive of Our Own and Etsy. Journal of Documentation, 77(2), 320–358. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-05-2020-0089

- Pugh, S. (2005). The democratic genre. Fan fiction in a literary context. Bridgend: Seren.

- Raw, A. E. (2020). Rhetorical moves in disclosing fan identity in fandom scholarship. Transformative Works and Cultures, 33. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2020.1731

- Rebora, S., Boot, P., Pianzola, F., & Kraxenberger, M. (2021). Digital humanities and digital social reading. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 36(2), 230–250. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqab020

- Romano, A. (2021, February 26). The internet’s most beloved fanfiction site is undergoing a reckoning. Vox. https://www.vox.com/culture/22299017/sexy-times-with-wangxian-ao3-archive-of-our-own-tagging-censorship-abuse

- Scharinger, C., Kammerer, Y., & Gerjets, P. (2015). Pupil dilation and EEG alpha frequency band power reveal load on executive functions for link-selection processes during text reading. PLoS One, 10(6), e0130608. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130608

- Silberstein-Bamford, F. (2023). The ‘fanfic lens’: Fan writing’s impact on media consumption. Participations Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, 19(2), 145–164.

- Stein, L. E. (2018). Tumblr fan aesthetics. In M. A. Click & S. Scott (Eds.), The Routledge companion to media fandom (pp. 86–97). Routledge.

- Stein, L., & Busse, K. (2009). Limit play: Fan authorship between source text, intertext, and context. Popular Communication, 7(4), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/15405700903177545

- Tosenberger, C. (2014). Mature poets steal: Children’s literature and the unpublishability of fanfiction. Children's Literature Association Quarterly, 39(1), 4–27. https://doi.org/10.1353/chq.2014.0010

- Trant, J. (2009). Studying social tagging and folksonomy: A review and framework. Journal of Digital Information, 10(1), https://jodi-ojs-tdl.tdl.org/jodi/article/view/269

- van der Bom, I., Skains, L., Bell, A., & Ensslin, A. (2021). Reading hyperlinks in hypertext fiction: An empirical approach. In A. Bell, S. Browse, A. Gibbons, & D. Peplow (Eds.), Style and reader response (pp. 123–141). John Benjamins.

- Vinney, C., & Dill-Shackleford, E. (2016). Fan fiction as a vehicle for meaning making: Eudaimonic appreciation, hedonic enjoyment, and other perspectives on fan engagement with television. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 7(1), 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000106

- Wiegmann, M., Wolska, M., Schröder, C., Borchardt, O., Stein, B., & Potthast, M. (2023). Trigger warning assignment as a multi-label document classification problem. Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics Volume 1: Long Papers, 12113–12134. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2023.acl-long.676