ABSTRACT

The original wave of Instapoetry, typically recognised by its typewritten font and generic axioms, was instantly divisive, with some decrying its linguistic simplicity as banal and others praising this same trait for its universal accessibility. Regardless of their controversial reception, however, the incessant production of today’s digital economy has required Instapoets to continuously adapt to their shifting environment. While a few Instapoet-influencers may have achieved true celebrity status, removing their original online posts and transcending to solely print publications, most Instapoets have continued to evolve with the platform in their practices for creating, managing, and presenting content. Surprisingly, however, such entrepreneurial adaptation does not necessarily contribute to disassociated intimate publics, where users are only vaguely connected by a loose exchange of likes. As evidenced by this case study on motherhood Instapoets, marginalised voices may sometimes build niche counterpublics where individuals mutually support each other for the good of the entire gift economy. Certain new hypertextual features, such as reels, not only contribute to increasing interpersonal user connections but even encourage more fluid co-digital collaborations. This survey particularly notes how content creators and consumers tag, share, and adapt reels to mutually strengthen the overarching motherhood Instapoetry community.

Introduction

When the born-digital movement of Instapoetry finally caught the attention of academics near the end of 2018, the general prediction was that this viral genre would not last long. Critics like Rebecca Watts, Thomas Hodgkinson, and others not only derided the poetry’s amateurism and apparent poor quality but denounced its ability to constitute “true” literature, since “endurance rather than fleetingness, is one marker of its quality. As Pound put it, literature is ‘news which stays news’” (Watts, Citation2018). Despite Watts’s insular prediction that this genre, tainted by “social media’s dumbing effect” (ibid) would quickly die away, Instapoetry is clearly still growing strong today. Even as the Covid-19 pandemic halted traditional outlets of readings and performances, writers amongst the burgeoning digital movement still thrived, especially as audiences locked down in physical and emotional isolation turned to online forms (Garg, Citation2021). Such resilience at least partly proceeds from the fact that this “short-form communication” can do far more than arrange clichéd aphorisms into pastel panels. Scholars willing to examine Instapoetry more closely have discovered that it is capable of leading grassroots feminist movements (Evans, Citation2023), alternatively widening or narrowing accessibility of marginalised voices (Knox, Citation2023; Gallon, Citation2020), or even affecting the amount of digital waste at a global level (Mackay, 2024).

However, it is important to recognise that six years later, this controversial art form, both lauded by proponents and condemned by its critics, has not merely endured but evolved almost as much as its platform’s continuously updated interface and algorithms. One major change is the fact that the most famous Instapoets are no longer the first profiles to appear under the tag #Instapoem or #Instapoet. In fact, the feed’s top results do not display poems by mega-influencers like Rupi Kaur, Tyler Knott Gregson, Christopher Poindexter, and others, nor even posts tagging their names as clickbait. Instead, searching hashtags about Instapoetry displays completely new users, with posts gaining hundreds of likes rather than the hundred-thousands garnered by Kaur’s early poems. The poems’ visual styles are different too – while there are still some typewritten, monochrome 2-liners, the feed erupts into a sea of other colours, backgrounds, fonts, and even columns of verse, often in multiple languages. With changed algorithms that holistically assess users’ engagement by tracking what they follow, share, save, and now watch, it is not enough to merely post regularly, though posting irregularly certainly does not help one’s cause. It is not even enough to post consistent types of content, since excessive similarity can actually hurt one’s visibility when readers become disengaged with the topic, perhaps explaining why the popularity of some original Instapoets has slackened.

Not that collecting millions more followers is necessary; having finally achieved a higher level of prestige, the most renowned Instapoets can essentially retire from the arduous process of curating their gallery for wholesale production. Poets like atticus, Cleo Wade, Warsan Shire, and the renowned Rupi Kaur – whose censored menstruation photo not only made her a feminist icon but instantly boosted her poetry’s popularity – can afford to take time off from their accounts for weeks or even months at a time, rather than posting multiple times daily. In many cases, their posts are no longer actual poems, but rather adverts selling their next book, performance, or merchandise. Such business-oriented posts may repel new followers but will not dismantle a long-established fan-base, who will readily purchase the “merch” of their favourite poets even if the content has shifted “seamlessly from digital to print” (Berens, Citation2024). Having finally attained the hard-earned status of having their print books on display in homes all over the world (Sarikaya, 2024), some writers are content to drop the #insta prefix that boosted their following and simply be “poets” (as some, like Lang Leav, have always insisted they are). Many pull their works off the platform altogether – why offer poems for free when they can be sold on Amazon for £12.99?

Yet it would be a mistake to think that just because some of the “original” Instapoets have decreased in digital engagement that the genre itself has suddenly disappeared. Instead, it has continually adapted and changed in length, style, and even language as users across the globe contribute to over 10 million posts tagged #Instapoetry and #Instapoet (which only accounts for a fraction of users who directly tag themselves as such).Footnote1 As Kathi Inman Berens notes, the poets who now contribute to the sprawling genre of Instapoetry have not only resisted the pressures of exclusion upheld by prestigious publishing and academic institutes, but their tones and styles have expanded beyond the somewhat scopic feminism of Kaur and other First Wave Instapoets, often using the platform for “wry self-expression rather than as springboards to book sales” (2024).Footnote2 Of course, an evolution towards unsettled self-critique rather than aesthetic pieces on self-esteem does not mean that all Instapoets have suddenly abandoned desires for monetary success; such a progression has been influenced by numerous factors, none the least a growing weariness of digital fragmentation (Liu & He, Citation2021). This ongoing unease that both producers and consumers face is not merely the result of information overload, caused by the sheer immensity of available content, but the fatigue of having to present, maintain, and manage impressions of one’s online self to others (ibid). Such exhaustion with self-presentation is even further heightened as users are compelled to participate in forms of “affective labour”, tangentially engaged in emotive content (Eder et al., Citation2019, p. 96) designed to increase audience numbers (Sujon, Citation2021, p. 221). This occurs because users reading (or scrolling) through a constantly flowing stream of sparsely worded but heavily sensory-based content feel moved to participate somehow, even if they do not recognise the depth of affect upon their emotions (Khilnani, Citation2023). Despite any of Instagram’s original claims of a creative utopia of meaningful, communal contributions (Frier, Citation2020, p. 103), users are often subsumed into a circle of permanent dissatisfaction on account of the platform’s embedded system of visual competition. This entire system of standardisation, according to Niels Penke, is always on the edge of collapse, precisely because of the emotional and mental overload that occurs when life has been so transformed into labour (Penke, Citation2023, p. 33).

What complicates this environment even further is how social media platforms like Instagram have exponentially increased general users’ opportunities and pressures to not only participate in the attention economy, responding to the affective pieces through “instantaneous impression events” like emojis or likes (ibid: 30; Bronson & Steele, Citation2024), but contribute with more labour-intensive products. In the past, users could simply utilise the platform’s hypertextual “vernacular” to reshare or retag the original post that affected them, even as they simultaneously contribute to another type of labour – transacted every time they unknowingly shed their data by reacting to posts. But apart from this lucrative method of collecting and selling user habits and personal information to external third-party advertisement companies, platforms like Instagram have increasingly encouraged users who might have identified as “viewers” or “audiences” in the past to more extensively generate their own content. Such “prosumers,” so labeled by Vincent Miller on account of their dual role in producing and consuming digital work, resign themselves to platform exploitation so long as they can enjoy the use-value of “freely” creating content (Citation2020, p. 107). While Miller primarily examines this hyper-exploitative level of prosumer capitalism in the form of music mashups on YouTube, it is undeniable that such features for participatory content creation and inter-performativity rapidly propagated on other platforms as well, particularly in the wake up the Covid-19 pandemic. Livestreaming, online gatherings, video-rooms, audio rooms, hangouts, short-clips, and other user-generated mashable media had existed before 2020, but became instantly more popular as TikTok, Facebook, Google, Zoom, and other platforms sought to further user-to-user engagement (Teague & Smith, Citation2021). Instagram was no exception, and perhaps one of its most popular ways of making users feel connected was through the introduction of the Instagram reel.Footnote3 Amid other features that instill a sense of both immediacy and intimacy, these forms of labour-intensive video hypertext are unique in encouraging sensations of interconnectedness within the very craft of content-making itself, as users react not only by resharing or “passively” liking other artists’ posts, but by making their own creative reels in response.

The question remains whether using these features, either to inspire original poems or parodic collages, can contribute to mutually-beneficial, multi-modal gift economies like those often celebrated on Wattpad, valuing inclusivity and non-hierarchical representation of marginalised identities (Vadde, Citation2017; Parnell, Citation2023; Thomas, Citation2020). Or would such tactics still construct perceived connections in a superficially intimate space, as is often the case with affective reciprocity within intimate publics (Lovelock, Citation2024; Abidin, Citation2015)? Whether the reel may truly encourage a “community of makers” (Berens, Citation2024), rather than millions of individual Instapoets competing to make their brand visible, will be examined in the following sections.

Methodology

To demonstrate an example of how Instagram’s reels may serve as a digital tool in progressing a typical intimate public toward a mutually-beneficial gift economy, this paper examines a niche group of Instapoets, who have appeared to transcend much of the “loose affinities and ephemeral connections” that characterise many online communities (Thomas, Citation2020, p. 85). The established affinity among these users often goes beyond a simple shared relatability in using the same platform (ibid), as they are connected not merely by a similar topic of writing or style, but by the unique challenges and rewards of a common identity: that of motherhood, and that of motherhood exhibited in a digital context.

Now, this paper is certainly not the first to examine the effects of digital constructs of motherhood, as many others have discussed dangers that can come from oversharing personal information, professionalising one’s identity on the basis of gender, privileging elitist heteronormative ideals, or monetising children’s lives long before they could give consent (Capdevila et al., Citation2022; Wegener et al., Citation2023; Heizmann & Liu, Citation2022; Knauf & Mierau, Citation2021). Other works also discuss the benefits of digitalising motherhood, as women stigmatised for public breastfeeding or mourning continual infertility find a place of belonging through shared vulnerability (Stenström, Citation2022; Locatelli, Citation2017). However, there remains a gap in research concerning the ways that using distinct hypertextual features on these platforms may help these women collaborate within their artwork itself, especially unique in a genre like Instapoetry, where writers accustomed to competing in a digital gig economy are predominantly compelled to work in isolation (Christiaens, Citation2022).

Indeed, before selecting a case study based on motherhood Instapoets, several other subsectors of Instapoets were also surveyed to compare their levels of affinity and collaboration, identified by their use of common hashtags. The unifying themes that could potentially cause a mutual contribution to collaboration were selected across a variety of identifying factors, from race to gender, levels of mental health to literary styles. While results did emerge demonstrating that users were combining tags to identify themselves as #ADHDpoet, #Asianpoet, #Blackpoet, #neurodivergentwriter, #asexualpoet, #rhyhmingpoet, and more, it was clear that these tags did not create large “folksonomies”, or a user-generated classification of post content, in comparison to tags related to motherhood. This made it difficult to identify communities where users even engaged with each other by tangentially following one other, let alone actively commenting or encouraging each other’s work on a regular basis. This was partly because many niche writers have so few followers (often between 10 and 120) and thus not enough “impression” capital to influence their algorithmic visibility, which in turn means they would likely not receive suggestions to follow other accounts linked by common themes. More importantly, many of these accounts did not primarily focus their content on a singular theme or shared experience. One poet might include the tag #lesbianpoetry for one poem but proceed to write about any variety of themes for the rest of their content.Footnote4 Others would identify with a trait in username only, like @neurodivergent.poet, whose naturalistic poetry primarily discusses the universe’s vastness, rather than any personal account of what it means to be neurodiverse. While there are certainly large groups where marginalised individuals can find solidarity from being Othered, like @growingupasian, or @autism_support_community, such collectives are typically based on spreading awareness about cultural, ethnic, or social challenges in general, rather than supporting a distinct group of artists shaping their artwork around these specific issues.

This is why the community of motherhood Instapoets, whose posts are linked by tags like #motherhoodpoet, #motherhoodpoetry, or #mompoet, stands in such contrast, as creators/consumers/prosumers alike utilise multiple methods of communicating and supporting each other on the platform.Footnote5 In addition to simply using common hashtags to establish a more-easily-navigated folksonomy, they share each other’s posts amongst themselves paired with extensive and regular comments, regenerate and rework each other’s reels and stories (almost always correctly attributing the original author), and participate in group jam sessions both within the platform and outside of it.

After noticing this distinction during my original general survey of potential Instapoetry groups, I began to focus on identifying instrumental motherhood Instapoets with whom to build my case study. Due to this paper’s emphasis on qualitatively examining the depth of these poets’ engagement within their community, particularly through their use of responding via reels, it was key to only select a limited number of users to evaluate with in-depth discourse and textual analysis. Having seen the benefits of applying Teun A. Van Dijk’s methodology of critical discourse to reading meaning and value from Instagram screenshots (Setyawati & Mulyana, Citation2020), which would be the primary form of collecting the visual and oral data of motherhood Instapoets’ posts, I applied Van Dijk’s approach here as well. Although Van Dijk includes three levels of structures within critical discourse analysis – macro, super, and micro – the concise though interrelated nature of these posts compelled analysis primarily of the macro and microstructures. In this case, identifying a post’s primary theme through its hashtags and imagery, as well as close-reading the “small parts of a text such as words, sentences, propositions, clauses, and images,” (ibid, p. 279) particularly any collaborative hypertextual features, would let me analyse how extensively these writers contribute to their community’s mutual well-being.

Additionally, the fact that these poets found, shared, and otherwise interacted each other through embedded links through hashtags made it logical that these case studies would also be narrowed down by continuing to use a folksonomy approach. This is not only because folksonomies rely on the collective generation of related values, concepts, and terms by users themselves (Avery, Citation2010), but because their aggregative nature recalls a “cumulative ‘oral tradition’” of narration typical to that shared by these poets, rather than a solely literate tradition with a one-sided, authoritative account (Wright, Citation2007, p. 234).Footnote6 Thus, examining these user-generated hashtags not only revealed the popularity of individual posts or users, initiating this study of motherhood Instapoets in the first place, but helped determine their levels of group contribution (Chakrabarti et al., Citation2023) and methods of hypertextual practice, including mutual tagging within reels.

Using both macro and microstructure discourse analysis with hashtags therefore enabled me to narrow the culminating case studies based on five key factors. These conditions required that each poet (1) use at least three of the combined identifying tags like #motherhood, #poet, #motherwriter, within the primary post or metadata (2) include multiple examples of their own poetry on their account, rather than just reposting others’ poems (3) demonstrate regular usage of reels, posting at least one within the last 6 months of February 2024, (4) follow at least one other motherhood writer, if not poet, and (5) tag at least one other motherhood poet or writer, either within the primary post or metadata, within the 6 months before February 2024. While some of these Instapoets were discovered by Instagram’s algorithm when I entered certain key terms, demonstrating some inescapable limitations of working within a platform’s search feature, at least half of the selected poets were found because they had already been followed by another selected poet, further demonstrating that these users were producing, consuming, and mutually contributing to each other’s content. Of the poets discovered through this search process, I only selected poets who displayed a public profile, who were thus openly promoting and exhibiting their accounts to be viewed on a large scale, thus avoiding potential issues of media ethics down the road. Ultimately, this selection process narrowed the observation set to 34 poets, divided into roughly equal groupings of follower counts. These sets included 9 users with several ten-thousands or even hundred-thousands of followers; 11 users with a medium range up to 20k followers; and 14 users with a smaller range of followers, with any number between 100–2000 followers. Having a varied selection enabled me to compare how even across the different levels of microcelebrity (or lack thereof), users similarly demonstrated examples of collaboration towards a gift economy.

It is important to declare that while this paper primarily started as a disinterested examination of one group of Instapoets amongst other niche collectives, the study came to include an autoethnographic approach as well. While writing this paper, I suffered a miscarriage, losing my second child. The poetry of these women, many who also spoke about the death of children and the impossible weight of carrying on in the aftermath, provided a cathartic, safe space to encounter feelings of grief, guilt, disbelief, anger, and longing. While the textual and discursive analysis of motherhood poetry’s use of reels to contribute to a gift economy remains an objective approach, I was also able to experience the benefits of being part of a gift economy firsthand. This autoethnographic methodology thus afforded a unique perspective into some of the direct applications of motherhood Instapoetry as authentic communal practice.

Core definitions of instapoetry

Before examining more deeply how reels have affected this niche form of Instapoetry, however, it is helpful to first clarify which terms will be used in this paper, since multiple interpretations of Instapoetry have already been established in the field. Generally, the genre had been recognised as one that combines visual and linguistic methods to express a short but emotional poem-as-post; indeed, one can never even post a poem unless it has been first uploaded as a single image (Penke, Citation2023, p. 1). Verbal and image styles may differ, but because the platform grants “normalization power” to posts that are brief and punchy, most Instapoems have been designed as both succinct and simple (ibid, p. 49). It is this precise ability to condense strong emotions into bite-sized panels that would compel visitors to subscribe and scroll through the rest of a user’s gallery, as opposed to spending extensive critical analysis on a single post. Whether expressing sorrow at the end of a relationship, or hope at the beginning of a new one, these ephemeral posts seemed designed for audiences to demonstrate their approval with a marketable digital exchange: clicking on heart emojis to influence the poet’s status and brand value. No matter how ardent or empowering a poem might be, the prominent display of a post’s – and a poet’s – worth in terms of public likes and follows reflects the permanent entanglement of an Instapoet’s creative identity with their platform’s inherent commerciality.

Who is classified as an Instapoet is still up for interpretation, however. While some have viewed Instapoetry as broadly inclusive of multiple kinds of platform posted by a large body of amateur writers (Soelseth, Citation2020; Tselenti, Citation2020), others have primarily limited the term to include a few select celebrity writers, such as Rupi Kaur, Nikita Gill, Atticus, R.H. Sin, and Hollie McNish amongst others.Footnote7

James and Polina Mackay tackle this quandary by tracking Instapoetry’s historical commerciality, suggesting the genre breaks into two branches: the narrow group of “capital-I Instapoets” who have been primarily published and publicised by Andrews McMeel, and the wider sector of lower-case “instapoets”, which refers to anyone who utilises social media practices in how they share poems or repost others’ poems (Mackay & Mackay, Citation2023).

This clarification is very helpful in providing a narrative for a previously nebulous genre, but there are also some challenges. Not all Instapoets have been published in traditional form, either by Andrews McMeel or by other large companies, although they have the same level of notoriety. And indeed, while Kaur and her contemporaries may have reached an elevated status now, their printed work adorning the front shelves of every Waterstones, there was a time when they were only known by their social media presence, which jumpstarted their chance of publicity in the first place. Although having the support of a large publishing company certainly increased select poets’ ability to achieve mega-influencer status, the phenomenon cannot fully account for ongoing Instapoets, many of whom have not published print or e-book collections.

Moreover, even if these famous names (as well as some up-and-coming writers) embody “Instapoets” in the way that Keats, Wordsworth, and Shelley epitomised the Romanticist movement, it is difficult to say that any poems pulled from the platform are still Instapoems, as opposed to other short-form poems, ranging from haikus to sijos. When the poem disappears from its platform, separated from the “metatinterface” that consists of “the movement of human/computer interaction from the desktop to the smarphone and cloud,” (Berens, Citation2024) all the special features that give an Instapoem its “Insta” flavour disappear as well. It loses both the self-editing element – the ability to be filtered, styled, and staged with strategic marginalia – as well as the audience element, including readers’ ability to like, tag, comment, share, or even hide text.

Such living data are of course all internal forms of hypertext, contained within Instagram itself. The platform does not even allow users to post hyperlinks (other than limited profile bios, which remain contained in the app) to keep users safely in-house, engaging with brands and ads directly on Instagram (Vahed, Citation2019). Nevertheless, Instapoets can work within these hypertextual and algorithmic boundaries to create evolving artefacts completely unlike any offline poem. Such freedom is what draws individuals to become Instapoets in the first place (Sanchez, Citation2024), often bypassing publishing gatekeepers altogether. The locational fragility of Instapoems’ hypertextual composition, which disintegrates as soon as it goes offline, or even when screenshot onto another online forum, is simultaneously what makes the poems so digitally engaging, allowing them to expand virally in a way that print poetry cannot. Whether they view themselves as amateurs or professionals, whether their poems appear in print books or on kitschy mugs, Instapoets are not individuals who merely happen to write online rather than on paper. Their ability to juggle multiple facets of being digital self-entrepreneurs, including creating, staging, editing, and marketing on Instagram’s immense platform, makes the capitalised prefix “Insta” even more appropriate.

What then marks the difference between the “original” Instapoets and those who came after, if it is an essential requirement of any of these digital-born poets to also become digital editors, marketers, and influencers? Ultimately, it may indeed come down to the environment itself, and of course the resources available to certain Instapoets starting out. As Penke notes, there is a certain “oligopostic” nature to Instagram, which not only applies to Instapoets but other Insta-celebrities as well (Citation2023, p. 38). A few users rose to stardom first – not necessarily because of “high-quality content”, as their content vastly resembles that of others – but because of sheer investment in time and money. Particularly in the case of Instapoets like Kaur, Drake, and others of the First Wave Instapoets, such status arose simply because they happened to achieve notoriety first, and this was immensely due to the fact that they brought existing followings and fan-bases from their original Tumblr accounts (ibid). Such an atmosphere, where astute individuals could achieve such instantaneous success in a relatively new platform – so long as they had a knack for visual style, an intense dedication to market strategies, and the ability to both politicise and represent empowerment over marginalisation and trauma – no longer exists. Nevertheless, the illusion remains that with enough persistence, branding, professionalisation, and ultimately, sheer will, Instapoets can achieve the same fairy-tale success of Kaur and the other “First” Instapoets (ibid, p. 45). In fact, because the sheer number of writers (and available readers) has only grown since 2018, when Kaur’s milk and honey debuted, aspiring poets must labour even more to curate their content with changing tools of the platform, also accounting for even more restrictive, though less visible, algorithmic processes.

Therefore, for this paper, I will continue to use the term “Instapoet” to refer to any poet who uses Instagram’s medium to produce and publicise their poetry. Whether they are lesser-known nano-influencers or more popular macro-celebrities (Ismail, Citation2023), these poets professionally choreograph content within the app’s unique haptics and metatext to engage readers’ emotions and increase impressions. I also acknowledge that although several Instapoets have partly owed their popularity to traditional publishers, as well as previous followings on other platforms like Tumblr, this initial group has both expanded and evolved as Instapoets have adapted their practices with a continuously shifting platform driven by attention-economics.

To exemplify this evolution, it was helpful to examine a specific strand of Instapoets as a case study – a group I have classified as motherhood Instapoets. The selection may at first appear unusual, given that some users do not always identify themselves as poets, let alone as Instapoets (though a lack of self-entitlement is not a definition, as already exemplified by other famous Instapoets rebuffing the title). Remarkably, however, these diverse individuals, connected by the common trials and joys of their motherhood journey, manage to not only create a unique gifting community but effectively utilise hypertextual trends to strengthen their bonds as writers, parents, and digital creators. This next section will outline how motherhood Instapoets have evolved beyond the generic content associated with many of the First Wave Instapoets, before demonstrating how using hypertext in the form of reels may enhance the audience-writer communal experience.

Key distinctions of motherhood instapoetry

What is motherhood Instapoetry? Defining a subgenre by a hashtag topic, as opposed to a specific writing technique or historical period, may appear unusual, especially when there have been poems written by, for, and about mothers for centuries. Nonetheless, the distinction is useful in differentiating between the specific work of digital creators and generic online collections compiled around a given theme. Such collections are of course important as they sample a “diversity of poems about the rich, messy, overwhelming experience” through history, as opposed to often one-dimensional portraits of women as mythical goddesses or sacrificial angels (Poetry Foundation).

Yet these collections are understandably still limited in number, not only because the “compartmentalized, domestic sphere” of motherhood was historically not deemed to be an “appropriate (or appropriately sublime) subject for poetry” in literary circles (ibid), but to over-emphasise such themes today could portray modern editors as once again boxing women into solely maternal roles. As such, Poetry Foundation, one of the largest and most influential of the online poetry libraries, lists only 84 poems under the topic “motherhood”, while Poemhunter.com and Poetryarchive.com are similarly limited in their anthologies, with 119 and 18 entries respectively. The women listed in these online exhibitions, spanning across extensive decades, nationalities, and styles, have no connection to each other, other than the fact that their “motherhood poem” appears on a public webpage, ready to pulled for the appropriate holiday or birthday card.

In contrast, the Instapoets tagging themselves as “motherhood poets” are accomplishing something uniquely different, consciously using the platform’s embedded tools to identify themselves as digital creators in an economy that prizes both creative agency and self-dissemination. And as they link their “public” Instagram brand with their other “private” selves as mothers(entrepreneurs/girlbosses/artists/feminists), these poets also directly contribute to building a living network of poetry and posts – one where women split amongst hydra-like roles and responsibilities can find solace in like-minded lullabies, dirges, and validation.

It is no wonder therefore that motherhood Instapoetry, which not only embraces newborn mums but women experiencing infertility, miscarriage, or empty-nests, is capable of filling the gap that online canonical collections have barely grazed. As of March 2024, there are currently 33.5 million posts dedicated to motherhood, 7.9 million to motherhoodunplugged, 4.4 million to motherhoodrising, and 3.8 million to motherhoodthroughinstagram. While certainly not all these posts are dedicated to poems about or by mothers, a surprisingly large number are. Instagram does not enable searching and counting posts by multiple hashtags, thus filtering which explicitly self-identify as poems on motherhood. However, one can circumnavigate this by Google-searching “site:instagram.com” with the desired hashtags. Using this roundabout method produces 66,100 results on Instagram linking “mother” and “poetry”; 27,000 for “mama” and “poetry”; and 42,000 for “mother” and “poet” alone, excluding any combination of these.Footnote8

The results reveal a wide variety of profiles. Some have hundreds of thousands of followers, like @JESSURLICHS, whose bio reads “#1 Bestselling Author” and hyperlinks her online showroom, selling her six books in print or digital format, along with gift-cards, clothing, and other merch. There are middle-range poets, like matrescentmuse or mum_doodles, with 16k and 13k followers, each with separate shops for selling accessories, décor, and pet supplies. And there are those, like amothersmusings_ and sammylee, with anywhere from a mere 100–1000 followers, yet still “speaking their truth”. Colour schemes move from traditional black and white to cheery pastels, with mixtures of hand-lettered scripts and “friendly” serifs, like Nawabiat or Playfair Display. Posts overwhelmingly feature photos, sketches, and paintings of babies and their mothers snuggling, nursing, or playing amongst scattered diapers and toys. What matters is not the specific formats, however, but how adeptly these mompreneurs and mombosses combine visual and linguistic methodologies with the platform’s hypertext and haptics. Whether or not their attempts are financially lucrative, it is undeniable that using Instagram’s tools helps to professionalise their poetry accounts, choreographing authenticity and ordinariness in a way that makes their content meaningful to their specific audience. What is unique, however, is that this professionalism exists alongside a genuine gift economy, an unusual occurrence considering Instagram’s tendency to create intimate publics.

Long before Instagram’s birth, Lauren Berlant had discussed the problem of intimate publics, wherein a thin web of intimacy is mediated amongst individuals based on interest in common themes, subjects, and most importantly, feelings, all of which are inflated in on a theatrical platform of shared trauma (Berlant & Prosser, Citation2011). People bolstered by having their “heartstrings pulled” (Hsu, Citation2019) feel deeply linked through passing, affective experiences (Berlant, Citation2008, pp. viii, x, 10), a longing further inflated by online maximalisation. The problem is not that such desires are inherently wrong, but they do often contribute to tenuously based connections in single-minded groups where sentiment holds currency rather than logic, reason, and fact – a tendency that often fosters Trump-age echo chambers (ibid) and encourages a fantasy of beloning rather than transformative power (Berlant, Citation2008, p. 270). Additionally, the assumption that simply identifying with “someone else’s stress, pain, or humiliated identity” equates with transformative action exemplifies the consequence of what Eva Illouz entitles “emotional capitalism”, an inheritance of psychotherapy since the era of Freud (Illouz, Citation2007). An overinflated sense of connection and sympathy is further exacerbated by the belief that such emotional voyeurism can be paid for, whether by a casually consoling comment, or the even more condensed digital token of a “like”. Of course, such affective resonance never ends up displaying itself in a single like or comment, but in countless instances of confirmation, claiming first that “we are all feel the same” (Penke, Citation2023, p. 70) and second that this value of shared feeling or affect, whether of pain or sorrow or passion, is simultaneously “a guarantee of Being” (Barthes, Citation1981, as cited in Penke, Citation2023, p. 113).

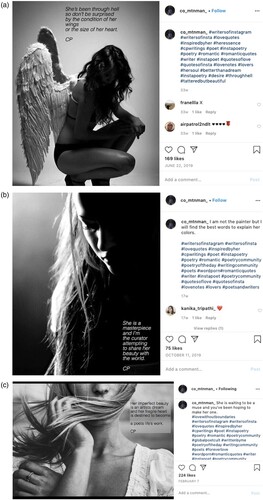

What are the consequences of inflating the value of collective emotion in this way, especially those related to trauma, abuse, violence, and mental illness, which are particularly productive in gleaning likes and follows (Penke, Citation2023, p. 72)? When these narratives are mediated for universal consumption on Instagram’s global stage, they often result in further victimisation, or “misery porn”, where the primarily female, Othered subject must repeatedly undergo cycles of trauma and “healing” to extend the gallery’s narrative, thus engendering more likes (ibid, p. 73). Take, for example, the Instapoems by co_mntnman_, whose photos usually portray a barely clothed female in docile, sexualised positions, continuously trapped in a cycle of suffering.

The poems’ language reveals the subject’s identity as inextricably intertwined with adversity, her only salvation to be masterfully “painted”, “translated”, “explained”, and “curated” by a masculine hand. Eyes always meekly downcast, she is both his art-piece and poem, ripe for painting precisely because of her “imperfect beauty” and “fragile heart”. While the veiled misogyny of co_mntman_ thankfully does not yet appear to have made it to print, similar sentiments like that of r.H. Sin’s post, “so many strong women began as broken girls”, have reaped over 45,000 likes before being unapologetically printed on T-shirts, mugs, and more. In other words, the hopeful ideals of “healing, happiness and the pious wish ‘you deserve better’”, which seem to clash with themes of trauma, suffering, and anxiety, are actually “two sides of the same coin” for many Instapoems, and it is this exact combination that makes them so lucrative, “commodifying the processing of experience” (Penke, Citation2023, p. 80).

Now I am not suggesting that the majority of Instapoetry uses affective labor in such a blatantly chauvinistic manner, nor imply that Instapoets who do professionalise their own trauma are not authentic. There is something troubling about “questioning the authenticity” of young women writing about their battles with sexual abuse, or indeed any other site of suffering, whether that be recovering from an eating disorder or seeking political asylum (Mackay & Mackay, Citation2023, p. 15). Nevertheless, even bodies that have suffered trauma can still become mediated sites of fantasy, especially when inflated to melodramatic scales, where “transformative” events of suffering outweigh or even condemn ordinary forms of passive and active life (Berlant & Prosser, Citation2011, p. 186). These consequences of emotive capitalism, conducted through transactional likes and follows on Instagram’s intimate public, perhaps inherently contributed to critics denigrating the First Wave of Instapoetry as short, hazy jingoisms. While brevity itself never equates to an absence of wit, the minimalism of many Instapoems combined with psychotherapeutic, guru-like diction could come off as superficial, even when describing intense suffering experienced in violent relationships. Balancing industrialised yet authentic emotions could often fall into an uncanny valley, as much of the speaker’s individuality was smoothed away to fit a global audience. Poems like those expressed below may seem inspirational during a rapid scroll, but these sweeping axioms about having “greater purpose” and “passion for it all” include very little of actual meaning, feeling, or active political means against contemporary ennui.

Noticeably, these poems are absent of metaphors, imagery, allusions, and other traditional poetic techniques, not only because these are more complicated to decipher, but such techniques often create more exclusive interpretations. Similar to co_mntman’s attempts to curate his beautiful masterpiece without any substantial description, these vast, melodramatic feelings seem bland in their lack of detail. They may advertise “spectacles of dramatic risk”, but do not deliver any real means of negating modernity’s “persistent numbness and exhaustion of meaningless labor” (Berlant & Prosser, Citation2011, p. 186). Because their delivery often appeared so similar, many poems became vulnerable to plagiarism; Kaur herself has been accused of plagiarising Nayyirah Waheed and others, taking specific, intensely personal experiences of Black women’s trauma and paraphrasing them to fit a larger audience (Belcher, Citation2023).

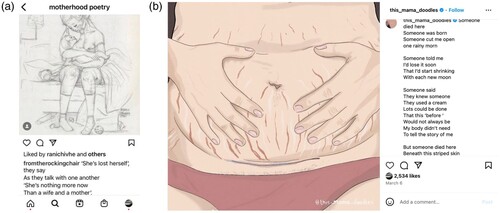

Contrast this with the sheer specificity of motherhood Instapoems, which are not merely longer but designed to craft vivid images with their words, ensuring other mothers can relate with their precise experiences. For example, daisielanewrites’ poems use several stanzas to paint highly specific scenes: the masked frustration at “sympathetic” gaslighting from single friends; the anger at unsolicited advice on sleep training; the scorn for Boris Johnson’s failure to isolate during lockdown whilst women like herself were forced to endure labour alone. The galleries of poets like thismamadoodles and fromtherockingchair feature personalised drawings as well, portraying tapestries of their own labour and postpartum scars.

This negotiation of the female body is another way that motherhood Instapoetry greatly contrasts with much of stereotypical First Wave Instapoetry, which depicts women’s physicality in melodramatic, even violent terms. Similar to the intimacy of reality TV dramas described by Berlant, some Instapoets (including several who identify as female) have so greatly sensationalised the spaces of women’s bodies that they become: “laboratories for assessing the relation of ambition to empathy, of ordinary boredom to the intensified event. The desire for brutality to generate events that show how ordinary gestures matter. The desire for sex to interrupt ennui, the ennui of living for a living” (Berlant & Prosser, Citation2011, p. 186). The result of this bodily renegotiation once again overemphasises “transfigurative” events, whether of pain or pleasure, and visually represents such representative-though-generalised “flesh-witnessing” by means of “stylized drawings” (Penke, Citation2023, p. 73). Penke’s use of the term “stylized,” is important, for the images that appear, despite their damage, are also designed to be extremely visually aesthetic (though often in Westernised stereotypes of slim-waisted, slim-legged, bosomy feminine beauty). Whether in the form of penned sketches or photographed vignettes, the subject must appear a work of art, with porcelain skin arranged with elegant patterns of cracks, blossoms, and bullet holes adroitly placed at discreet locations. In terms of these galleries’ narratives, experiences of abuse are alternately voiced in first-person or omniscient third-person voice, depicting female subjects arranged in positions of visual sexual vulnerability, violated by scissors, swords, or wires, yet linguistically paired with cringy terms like “strong”, “confident”, “calm”, “satisfied”. Consensual descriptions of sex are no better, with phrases akin to “she was scared but when I tenderly parted her thighs, she opened her petals and cried my sweet nectar”, or even Atticus’s now-famous line, which has also become a highly popular tattoo: “Love her but leave her wild” (Atticuspoetry, Citation2016).Footnote9 The sheer formlessness of such poems demonstrates the precariousness of over-mediating objects to produce dramatic sentiments for a global audience ().

Figure 1. (a–c) Examples of Instapoems capitalising cyclical victimhood of the poetic female subject. Photos by @co_mtnman_ on 22 June 2019, 11 October 2019, and 7 February 2020, Instagram. Screenshots taken by author on 23 March 2020.

Figure 2. (a,b) Examples of axiomatic Instapoetry. Photos by @pagesofrebirth on 17 February 2021 and @tylerknott on 2 March 2020, Instagram. Screenshots taken by author on 18 March 2021.

Figure 3. (a,b) Examples of nuanced physicality represented in motherhood Instapoetry. Posts by @fromtherockingchair on 17 November 2022 and @thismamadoodles on 6 March 2023, Instagram. Screenshots taken by the author on 12 December 2023.

Figure 4. Examples of mutual support in a co-digital community, represented by Rebecca Schiller’s “Mothers Who Write” retreats. Post by @rebecca.schiller on 15 July 2020, Instagram. Screenshot taken by author on 09 December 2022.

In a sense, motherhood Instapoetry certainly contains just as many physical descriptions as does typical Instapoetry. However, this form of “flesh-witnessing” is much different than the “stylized” canvasses used by Rupi Kaur, Charly Cox, and others who follow in their footsteps (Penke, Citation2023, p. 73). Instead, the vivid depictions of the extreme changes mothers must endure, from sagging body parts, stretched skin, and vaginal tears, are framed quite differently. There is neither extreme glorification nor mortification at the graphic physical tolls of birth and postpartum recovery but a more nuanced form of acceptance, a frank acknowledgement of both the beauty and discomfort entwined within their altered bodies. Scars exist in all forms, but they are not the chief mark of one’s identity; labour is painful but does not become the all-consuming, defining moment of one’s life. While many poems do address the occasional highs and lows that come from deconstructing their new identities after this form of “death”, there is much more description of the day-to-day milestones. Because the journey of motherhood is a journey, there is a continual sense of growth, as both mothers and their children develop. This starkly contrasts with the recyclable narrative of “empowerment” that appears in many First Wave poems, where speakers re-circulated posts on traumatic events to repeatedly draw a voyeuristic audience, ultimately rejecting any “ordinary forms of care, inattention, passivity, and aggression that don't organize the world at the heroic scale” (Berlant & Prosser, Citation2011, p. 186).

This is not to say that motherhood Instapoets are any less professional in their manner of digital publishing. Microcelebrities as a whole build their brand by intentionally diminishing the mysterious para-social divide that was once associated with traditional celebrities, revealing an authentic self (or part of an authentic self) that matches with their brand and audience (Mishra, Citation2021). Yet sharing similar practices with intimate publics does not mean that all mediated, social entities are built around superficial networks of emotional exchange. In some cases, niche, self-representative communities develop, whether by forging relationships around nonbinary sexual identities (Duguay, Citation2019), using “testifying” microstreaming as a form of resistance against structural racism in gaming forums (Chan & Gray, Citation2020), or interrogating religious authority by renegotiating female evangelical and political influence (Gaddini, Citation2021). In fact, it is the “virtual-ness” of these “affinity spaces” that enables such individuals isolated by disempowerment and marginalisation to find each other in the first place, and then create strong bonds to “activate for change” (Thomas, Citation2020, p. 84). As such, these motherhood Instapoets, digital creators appealing to their audience through built-in platform tools and eclectic forms of entrepreneurship, can often accomplish much more than a typical public produced by other Instapoets. It is not just that these poems’ detailed content is often more affective at mutual catharsis with their specific, targeted set of readers, releasing intense feelings trapped beneath their breasts whilst nursing or rocking in the dark. Rather, such communities formulate kinds of “counterpublics”, meaning publics that maintain, whether “conscious or not, an awareness of [their] subordinate status” to the dominant horizon (Warner, Citation2002, p. 85). Such spaces provide “parallel discursive arenas where members of subordinated social groups invent and circulate counterdiscourses to formulate oppositional interpretations of their identities, interests, and needs” (ibid) – in this case, alternate interpretations of motherhood’s complexity, as opposed to being “just moms”.Footnote10

As Warner states, such alternate forms of agency could then cultivate “spaces of circulation in which it is hoped that the poesis of scene making will be transformative, not replicative merely” (ibid, p. 88), an element directly visible in the manner that motherhood Instapoetry communities encourage mutual performative discourse. The affective linguistic labour performed by motherhood Instapoets in their poems, captions, and even tags overtly invite readers to reciprocate this labour in kind, thus forming collectives known as “gift economies”.

This term is not a new one, not only having been introduced in the 1920s by Marcel Mauss and Bronislaw Malionwski to describe practices of tribal peoples in the Trobriand Islands (Peng, Citation2022), but in more recent years to delineate other forms of communal exchange, including the circulation of digital knowledge, codes, and even software as “public goods” (Fuchs, Citation2008, p. 162). While there are variances between digital gift economies, a predominant characteristic is that they repeatedly intertwine long-term, mutual bonds of reciprocation, bonds that are wrapped around affective or even “erotically” charged feelings of shared experiences, particulary of art (Vadde, Citation2017, p. 32). This is not to say that the digital gifts exchanged are not commodities, whether they be memes or poems. Nevertheless, there is a mutual acknowledgment that treating the gift solely as profit, or its platform of exchange as a pure market economy, will reduce the collective benefit for users as a whole, by destroying the ontological, creative value of the gift, and with it the shared identity of gift-givers and receivers as joint creators (ibid, p. 33). The complexity of such networks, often involving camaraderie, friendship, and even sacrifice in expectation of nurturing further gift-giving, greatly contrasts with the fragile, brief connections of intimate publics relying on capitalistic values of “scarcity, alienation, and self-interest” (Hoeller, Citation2012, p. 89). On Wattpad, Vadde exemplifies how this gift economy works to the benefit of all amateur art-contributors, particularly in the genre of writing novels. So much of the audience is present in supplying encouragement, critique, and guidance for the story’s progression that the “line between writing a story and publishing it virtually disappears. An amateur writer on Wattpad can cultivate a fan base before ever completing a novel” (Vadde, Citation2017, p. 37). This mutual, “free” gifting of labour and time in the form of communal comments not only benefits the original amateur poster seeking advice for their first draft, but allows the rest of the community to learn and grow from the thousands of distinct, condensed peer reviews, all while maintaining the emotional satisfaction of having contributed to the greater public good in the first place.

Similar to writing gift economies like Wattpad, where devotion to shared practices and interests is exhibited through “public displays of reflexivity and attention” (Vadde, Citation2017, p. 28), there appears to be an underlying dedication amongst motherhood Instapoets and their readers to cultivate genuine, reciprocal encouragement. Whether this is forged through detailed enthusiasm over a writer’s use of poignant imagery, or several veterans buoying a sleep-deprived new mum with an arsenal of generational teething tips, these interactions seem intent on strengthening the larger community’s well-being through positive support for individual participants. As seen through the above post by @rebecca.shiller, navigating the peaks and trenches of mothering, whilst simultaneously negotiating the unique challenges and stereotypes as mother-writers, is better together than alone.

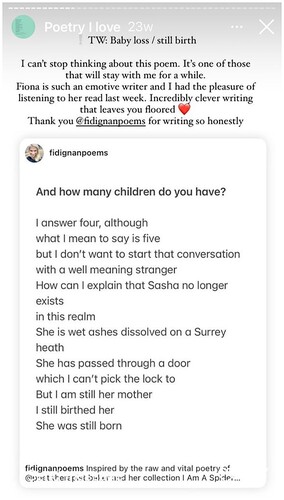

A clear example of how this authentic gifting environment – divergent from Instagram’s typical transactional “follow4follow” atmosphere (Penke, Citation2023, p. 84; Sarikaya, 2024) – affects the poems themselves can be found by close-reading the microstructure of the layers of “tagging” support within the IG Story screenshot of the following wrenching poem by @fidignanpoems, which describes the agonising loss of experiencing a stillbirth and having to lie about it to well-meaning strangers ().

Figure 5. Examples of mutual poetic-gifting through tagging and re-sharing. Screenshot of “And how many children do you have” by fidignanpoems, shared through the “Highlight” feature by @motherhoodispoetry on 5 July 2022, Instagram. Screenshot taken by author on 13 December 2022.

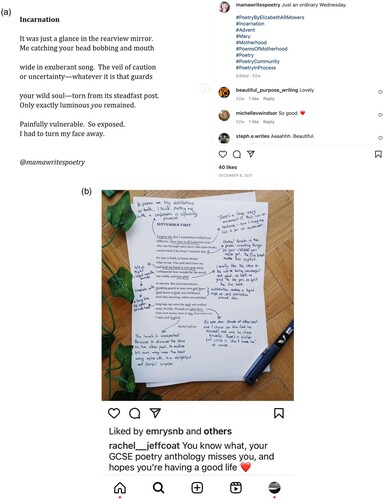

Figure 6. (a,b) Examples of mothers’ intimate Instapoetry to their children. Posts by @mamawritespoetry on 8 December 2021 and @rachel__jeffcoat on 1 September 2022, Instagram. Screenshots taken by author on 13 December 2023.

The titular question, “And how many children do you have”, immediately drops the reader into a state of painful bewilderment, precisely mirroring the awkwardness of giving a “simple” numerical answer, as the speaker’s thoughts are dragged through the tactile image of “wet ashes dissolved on a Surrey heath”. Symbolic enjambment, causing the child’s existence to disintegrate on one line before reappearing in the line alluding to another realm, as well as homonyms “still” binding the mother to her child after “still” birth, all work to sharpen the speaker’s grief through both visual and aural means. Yet besides creating a space to narrate the acute yet often hidden anguish of miscarriage, the poem as a “screenshot” artefact also mediates a relationship by at least three actants within the hypertext. Notably, in the bottom text of the initial post, the poet fidignanpoems herself first tributes the “raw and vital poetry” of another motherhood Instapoet and psychotherapist: Flora Cruft, also known as @poet.therapist.baker, author of I Am a Spider Mother. This accolade of inspiration is itself then screenshot by the poet @motherhoodispoetry and shared through Instagram “Highlights”, which are key posts always made accessible to readers above the primary gallery via distinct hypertextual links, unlike transient Stories that disappear after 24 hours. In addition to motherhoodispoetry’s “Highlight” tabs for all the poetry collaborations she has crafted with other women, she has a special “Highlight” section to share an ongoing collection of over 47 poems by other motherhood poets who have personally inspired her. The collection, including this screenshot, is accompanied by literary feedback as well as personal support to her readers. Such a communal culture seems vastly different from the culture of competition and plagiarism projected by original Instapoets, many of whom do not deign to follow their contemporaries.Footnote11

The sense of mutual sharing not only appears within the authors’ primary content, however, but within metadata beneath posts as well. Margins contain hypertextual tags, shares, and comments full of detailed feedback and encouragement, both about the poem itself and the challenges of motherhood. There is advice on nursing positions and burping techniques, but also shout-outs to both writers and readers to trust their own power and worth despite their exhaustion. Poem creators and consumers share their greatest fears, guilt, and joy with strangers, confident of feeling seen in a manner that not even family can offer. Of course, technically any adept nano-influencer would use similar tactics to authenticate their brand, even occasionally accepting an audience’s fashion recommendation (Mishra, Citation2021, p. 74). Yet it is difficult to see the Zoellas and Camgirls of YouTube fully bridging the celebrity distance with viewers by sharing their stage and turning fandoms into equal communities of peers. Many of the marginal links shared by these Instapoets even encourage engagement outside the platform to specifically enhance creativity, from collaborative poetry jams to Lockdown Zoom Mama venting sessions. If any group could transform a loose intimate public into a gifting community knit around core values of both exchanging art as well as improving craft practices, perhaps it would be motherhood Instapoets.Footnote12

Adapting the reel

Thus far, I have demonstrated how a single branch of Instapoetry has evolved in a way that could move beyond the tenuous networks that typically develop on its platform. However, it is important to realise that these connections have not only deepened on account of greater content and linguistic specificity, or even from a collective dedication to a particular counterpublic space. While some may claim that the biological instincts rooted in maternity inherently help to cultivate “herd”-like bonds between mothers anyway, there are also specific hypertextual features embedded in the platform that allow this sub-genre to flourish even more expediently. We have already seen some examples of meaningful hypertext embedded within the margins, such as the tri-fold tags of attribution in the poem by @fidignanpoems. However, there are other cases where the hypertext is the primary content, making it even more conducive for generating communal, reciprocal poetic creations.

This is where it comes in handy to examine a specific, more recent feature of Instagram: the reel. Reels are the next in a long line of video adaptions first jumpstarted when Twitter allowed users to share 6-second videos, known as “Vines’.Footnote13 In response, Instagram quickly enabled 15-second videos, before eventually developing Boomerangs, which transformed photo-bursts into video loops. Instagram released its full version of stories in Aug 2016, directly copied from Snapchat’s video function (Constine, Citation2016).Footnote14 These small videos or photo montages initially did so well on Instagram that even Facebook and Youtube adapted them, yet it soon became apparent that stories’ ephemerality – an expiration of 24 hours – did not suit a market designed to create viral brands. Adding live video features in November 2016 would increase “immediate authenticity” but curtailed the video’s playback time to a mere hour. To gain engagement, digital entrepreneurs needed something that could last longer, with options for unlimited re-viewing. Enter the “reel”, which started as a competitive reaction against Tiktoks. In stages, Instagram lengthened reel time from 15 s to 90 s (now surpassing Tiktok), providing users more time to engage with content (Lishchuk, Citation2023).

Despite the opportunity to increase impressions, traditional Instapoets seemed to avoid filling their galleries with reels, at least at the outset. This was partly because a video’s cover screengrab looked smeared and blurry in comparison to the carefully curated original galleries of text and photos. Galleries full of images also made it difficult for users to find video files randomly mixed in, at least until Instagram resolved this by creating a separate reels tab. Most importantly, original Instapoems were extremely short, with 2–3 lines of text filling up 2–5 s of video, which did not make for impressive content.Footnote15 Thus, many early Instapoets primarily used reels to introduce their brand or advertise merchandise in the Story stickers that float in the white space below the bio and above the main feed.

Reels function perfectly for longer Instapoems, however, especially those appealing to aural elements. Surprisingly, reels re-expose the genre back to more classic techniques, from alliteration to rhyme to tetrameter, as Instapoets must suddenly consider not only how their poems look but sound when spoken aloud. The reels can be paused but not rewound, and instantly replay in loops unless users swipe to the next video. The addition of music makes reels extremely memorable, appropriate for many motherhood Instapoems as modernised lullabies.

What truly sets reels apart from traditional, re-shareable hypertext, however, is the fact that these pieces are specifically designed to be reworked and recreated: an element that even better suits them for a creative gift economy, where participants mutually contribute to the success of each other’s artwork. Whilst Stories allowed users to privately comment on each other’s posts with positive feedback or advice, reels encourage greater levels of mutual prosumership, where consumers become producers by responding in kind with their own reels. This is partly due to the reel’s inheritance from Tiktoks, which originated as dance-offs challenging users to make spin-offs – often choreographed better than in the initial video. Instagram offers several easy in-app options for anyone creating or modifying reels, even if they have no knowledge of the code behind these features. Toggles can curate audio, filters, and speed, as well as hundreds of templates, stickers, fonts, and drawing tools. Users can tag people and products, while incorporating locations, polls, quizzes, fundraisers, or re-shareable links on Facebook. Most importantly, there is a hypertext sticker that encourages users to “add yours now”, so anyone can recreate any reel for their own purposes – with the added bonus of eliminating opportunities for plagiarism, since special effects always tag and tribute the original creator, unlike screengrabs of still photos. The reel thus represents both the highest form of praise and creative challenge, whether the reel is rewritten in the spirit of inspiration or to enhance its original quality.Footnote16

To see how such re-creation works with motherhood Instapoetry, one has only to view the viral reel of the poem “May We Raise Children”, by Nicolette Sowder. Sowder might well be called an “Instapoet+” because she not only writes poems on “co-parenting with Mother Nature”, but also takes on several other roles as well, the epitome of a mompreneur. She is the self-claimed creator of wildschooling and moon clubs, and aims to “decoloniz[e] place-based education” by selling printables, crafting supplies, and wilderness kits. Sowder’s famous poem was later taken up Christi.steyn, a spoken Word artist and poet, who is incidentally one of the most famous “Instareel” poets as well, given that all Steyn’s poems are reels. In addition to orating her own poetry, however, Steyn also narrates others’, and her reading of “May we raise children who love the unloved things” is one of her highest-ranked videos. This poem likely went viral because Steyn’s soothing voice perfectly matches the poem’s inspirational message: that children encouraged to empathise with bugs and weeds will become adults who advocate for the defenseless. While Steyn eventually pulled her video off Instagram, (though not off TikTok), her reel’s audio has remained and even proliferated its virtual presence in the form of re-creations by thousands of users, some with 18,000 views, others with 184. Steyn’s reel has even been adapted and translated into multiple languages, whether by Dutch momfluencer @eenbeetjehippiez or within a collaboration between children’s decoration store @o.pequeno.ninho and digital creator @liasuemachado from Brazil.

“Two Little Shadows”, author anonymous, is another famous reel-poem that celebrates a mother’s relationship with her children, even if their continual clinging slows her productivity. The poem was taken up by the well-known Instafluencer, @lindseygurk, who has over 695k followers and posts her own raps and parodies next to reels on fashion, skincare, and humourous anecdotes of her mischievous children.Footnote17 This single reel alone has over 2.4 million plays on her profile, but it is impossible to tell just how many times the audio itself has been replayed since it has been used in over 14,600 new reels. Jessica Urlichs, one of the most followed of the motherhood Instapoets, holds even higher records for many of her poems. In the spirit of reciprocal creativity, her reels, like the extremely popular “To My Firstborn”, often include such captions as “Feel free to use the audio if you like ![]() ” (Urlichs, Citation2022), thus presenting her poem as a gift not only to her child, but to the audience whom she encourages to adapt the reel in new creative ways. The reel has been played 4.9 million times and recreated over 29,100 times, demonstrating just how prolific this form of hypertext can become amongst a gift economy united not only by the common interest of motherhood, but a mutual commitment to helping other motherhood writers.

” (Urlichs, Citation2022), thus presenting her poem as a gift not only to her child, but to the audience whom she encourages to adapt the reel in new creative ways. The reel has been played 4.9 million times and recreated over 29,100 times, demonstrating just how prolific this form of hypertext can become amongst a gift economy united not only by the common interest of motherhood, but a mutual commitment to helping other motherhood writers.

The communal influence of reels

From this brief examination of how motherhood Instapoets use the hypertext of reels, it is clear that this unique option for audience adaptation could enable members of a gift economy to proliferate creative responses in a more immediate, reciprocally beneficial manner, as posters and re-posters are inspired by each others’ encouragement and attribution. But what are the long-term consequences of these types of motherhood Instareel poems, particularly in the larger market of platform visibility? It is important to remember that despite the seemingly immense amount of freedom to discover and recreate these new pieces of art, it is difficult to determine exactly how much content is controlled by Instagram’s algorithms. How do users know that they are truly exposed to a wide range of reels when scrolling trends offers even less autonomy than specifically searching a hashtag? While algorithms are partly based on our past behaviours and preferences, they are also “designed and maintained by the engineers of monopolistic tech companies”, allowing them to warp, manipulate, flatten, and sift what will become popular according to the “biases of race, gender, and politics as well as by the fundamental business model of the corporation[s]” that own them (Chayka, Citation2024, p. 15). Thus, even if when the algorithm misinterprets our data through “surveillance capitalism” (Zuboff, Citation2019), offering feeds and content we don’t necessarily desire, we cannot directly change it, and must continuously, passively adapt to its “recommendations” by repeatedly swiping left. There are also moral questions at stake regarding the ethics of parents capitalising on their children’s global exposure, with kids becoming social media stars at 2 years or 2 months, all without their consent (Wegener et al., Citation2023, p. 3227; Locatelli, Citation2017, p. 10). What kind of world will these children face, with this overabundance of digitised, professionalised displays of emotion, where everyone is intimately familiar with tools for filtering, editing, and curating multiple versions of themselves? And how will this affect their self-esteem and self-presence as they learn that algorithms have privileged some of their faces over others since birth? Footnote18

But despite these questions, this study demonstrates there is also cause for optimism. While Instagram itself naturally encourages loose intimate publics, many of these motherhood poets and their readers seem to be dedicated to pushing against this structure, instead contributing to co-digital gift communities. As a kind of counterpublic to historically biased, dominant views of motherhood, these forums provide a safe-brave space for women to share and vent nuanced narratives of joy, anxiety, frustration, and growth. In addition to providing a place for women to get advice for weaning, napping, or simply surviving the day, these literature-based communities offer something distinct from other motherhood groups – the opportunity to gain peer support about their writing and creative practices, whether they be an already published influencer or a budding Instapoet with less than 50 followers. And while reading an Instapoem does not make one less physically tired, after multiple midnight wakeups to nurse, pump, and change, readers at least have the solidarity in knowing they are not alone. The invisible narrator and photographer, always filming her children and partner behind the scenes, can finally feel seen. As Lauren Berlant stated, one of the positive elements of an “attentiveness to affect” is that it “encourages us to imagine ourselves beyond the present: even if feelings of exhaustion, indifference, or disillusionment may have been naturalised, that doesn’t mean they’re natural” (Hsu, Citation2019). Together, these motherhood Instapoems help women to “refuse to be worn out” for good.

This return to the discussion of affect theory also observes a new outcome – motherhood Instapoetry’s ability to not be merely affectual but effectual, causing readers to move from sympathetic but passive imagination to actively responding with their own poetic creations. Whether designing a reel from the ground up or reworking another Instapoet’s poem, audience members utilise an extensive skillset to meticulously craft their collages of photos and videos. Those who decried the brevity of the First Wave of Instapoems, and the fact that there is supposedly no time to think about a poem’s linguistic features or structure, have never tried to make or remake a reel. After listening to the same chorus repeatedly while trying to seamlessly assemble, match, and edit each of the film’s visual and aural elements, it is difficult to avoid having the intricacies of the poem’s every syllable drilled into one’s brain. Yet the process requires far more than simply splicing the reels at precise visual points. Writers must now also pay more attention to the musicality, lyricalness, and even meter of their poems – particularly appropriate considering that before “reels” were strips of film, they were rhythmic dances in 2/4 time. Most fascinatingly, the majority of individuals exhibiting these essential skills appear to be autodidacts, digital creators who have become experts at composing, editing, and ultimately marketing their art even as they juggle their countless other roles.

This brings us to a third, critical consequence of this trend of self-taught professionalism through such reel accounts: users’ ability to inhabit and exhibit multiple creative identities. For example, take the video creator and mum-of-five @emilyvondy, who has received hundreds of thousands of likes for her lyrical poems (some put to music, some without) about the beautiful chaos of being a mother. While Vondy has received over 14.5 million plays of her piece “Nap Trapped”, 30.4 million for “Uterus Fanny Pack”, and hundreds of millions of likes and remakes of her other poems and songs, her content is not constrained to a single genre. Other popular reel forms include raps about her comfy pajamas, maternity photoshoot fashion tips, positive chants for labour contractions, and “mom-fessions” about eating a lunch of pre-licked Oreos while yelling at her children to quit playing in the washing machine. Such intersections are a reminder that not only is Instapoetry capable of escaping prescribed formats, but its makers do not need to fit in narrow boxes of traditional authorship. While an economy that demands self-management of multiple gigs can be exhausting, it can also be liberating for savvy digital creators, occupying multiple identities without appearing duplicitous or inauthentic. The galleries of these Instapoets/film editors/social media entrepreneurs/lifestyle influencers show that it is possible to not merely hop from role to role but to inhabit them simultaneously, like a set of matryoshka dolls, each mothering the next inside itself.

Eschewing traditional constrictions and confines might have a fourth, long-term consequence, one more of a question than a given since it remains to be seen: could such a shift in attitude toward the fluidity of digital-born and hybrid poetry, produced by “professional” amateurs, also benefit our children, the next generation of writers and readers? What would be the effect if children listened to poems about them, composed for them, by women who have created their own safe-brave space of peace and solidarity, who by being Instapoets + publicly demonstrate their ability to be more than carers? It is natural to be self-insulated as a child, but would adolescents feel a closer connection with their parents upon hearing raw, anguished lines like “I cry hidden in loos / I scream alone in my car … We are parents but we are people / We are snot-rags and we are dreamers” (McNish, Citation2016)? By hearing even more rhymes and lyrics paired with the technical knowledge of utilising alternative types of text and hypertext, they might be better prepared for navigating a post-digital society. Perhaps, when someone has to speak for those who have no voice, or even break barriers so the voiceless may speak for themselves, they may, as self-aware, responsible digital citizens, “be the ones” (Sowder, Citationn.d.). But most importantly, as demonstrated in the following Instapoems, our growing children will know even more firmly in an increasingly fragmented and filtered world, that they are seen, and they are loved.

Ultimately, regardless of the effect motherhood Instapoetry may have on future generations, its current, nuanced progressions clearly demonstrate both the evolution of the larger genre and its capacity to move beyond the typical intimate publics of the platform. Scholars would do well to examine Instapoetry more holistically, rather than isolating their critique to a single aspect of the genre, as well as extending their survey outside of the limited First Wave of influencers. The professionalism or amateurism of an Instapoet, the presence or lack of prestige and saleability, the influence of reader impressions and communal commentary, the use of hypertext and platform tools to design, edit, and market their work – none of these aspects alone should constrain or determine the poetic ability of a writer. Rather, Instapoets’ ability to incorporate all these elements into their written labour as well as their online brand, along with a distinctive ability to maintain a community where mutual gifting still thrives, demonstrate the innovative fluidity that is advantageous and even necessary when labouring in a digital creator-prosumer economy. By examining the evolution of these more-than-mums, more-than-poets, and their adaption of shifting hypertextual forms within their creative practice, we may see a way for creators and readers bombarded by a maximalised internet to move beyond mere digital resilience to digital solidarity.

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to my sons, the wellspring of my poetry, and my husband, my greatest encourager and friend. I also acknowledge the Digital Humanities Institute at the University of Sheffield for their tremendous support of my research, and all the motherhood Instapoets whose words offered hope during the long, sleepless nights. Most of all, I dedicate this work to my second child, Glory Jubilant, carried to glory in the midst of writing this. I carry your heart with me, I carry you in my heart.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The global spread of Instapoetry is an important discussion, and within an edited collection with EJES, I discuss the significance of examining the similar yet distinct trends that emerge when Instapoetry is written in different languages. Indeed, it would have been helpful to examine whether the same observations of motherhood Instapoets applied when hashtags building the folksononomy used a language other than English. Due to the restrictions of time, this paper will not be able to cover such an international reach, although such a study would be highly impactful for the future. As I discuss later in the paper, however, translated, re-worked reels from international poets, such as Dutch influencer the@eenbeetjehippiez or the accounts of @o.pequeno.ninho and digital creator @liasuemachado from Brazil, reveal that many motherhood Instapoets around the world would still connect to their audiences using similar strategies as those discussed here.