ABSTRACT

This article analyses Shelley Jackson’s 1995 hypertext novel Patchwork Girl (PG) through the lens of intersectional feminist digital humanities scholarship. PG is a fascinating electronic literature artifact because scholars pronounced hypertext dead almost a quarter century ago. Hypertext was confirmed dead by Nick Montfort in 2000, though Montfort stipulated that the hypertext corpus could be resurrected. This article argues that PG’s various resurrections qualify it to be considered an undead hypertext and re-centres hypertext’s strong ties to intersectional feminist digital humanities scholarship, taking up Roopika Risam’s call to resist the reinscription of the exclusionary universal subject so often defaulted to in contemporary scholarship and demonstrating how PG creates the antithesis to an exclusionary universal subject through the literal and metaphoric multiplicity of its titular protagonist. With a body made up of pieces of other women’s bodies—pieces which retain their original personalities—Patchwork Girl is, as Marie Mulvey-Roberts dubbed her, the Everywoman. And as the Everywoman, she is able to take on the role of inclusionary universal subject, thereby making her a prototype of the sort of character capable of dismantling the restrictive notions of the exclusionary universal subject that Risam so adeptly identified.

I am tall, and broad-shouldered enough that many take me for a man; others think me a transsexual (another feat of cut and stitch) and examine my jaw and hands for outsized bones, my throat for the tell-tale Adam’s Apple. My black hair falls down my back but does not make me girlish. Women and men alike mistake my gender and both are drawn to me …

Born full-grown, I have lived in this frame for 175 years. By another reckoning, I have lived many lives … I am never settled.

I belong nowhere. This is not bizarre for my sex, however, nor is it uncomfortable for us, to whom belonging has generally meant, belonging TO. (Jackson, Citation1995, {I am})

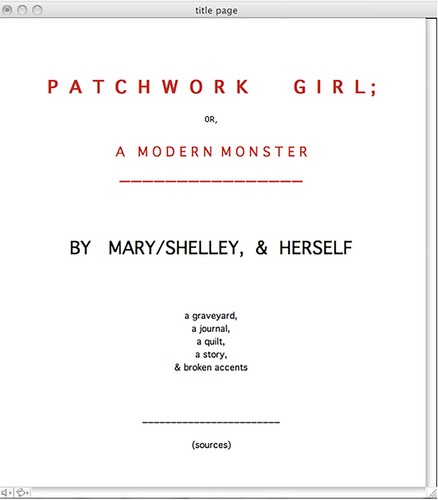

So begins one of the many storylines in Shelley Jackson’s hypertext novel, Patchwork Girl. In this excerpt, Patchwork Girl is giving a physical description of herself and alluding to the fact that she is monstrous in many senses of the word. She is physically large, made up of disparate pieces, and her very being is a blurring of boundaries. Patchwork Girl is a fascinating upgrade to Victor Frankenstein’s original monster, and she is ever aware of her genealogy, writing, “I was made as strong as my unfortunate and famous brother, but less neurotic!” ({I am}). Much more than a retelling of Frankenstein, Patchwork Girl is an appendage to Shelley’s masterpiece and one of a very small handful of hypertext novels that retains its relevance as demonstrated by the fact that it continues being resurrected for analysis by scholars from a range of disciplines. Bell (Citation2010) used Patchwork Girl to develop her Possible Worlds Theory for narrative analysis, Latimer (Citation2011) resurrected it to examine posthuman theory and reproductive technologies, and Ensslin et al. (Citation2020) recently employed it in their Writing New Bodies workshop to explore and establish what they call “applied e-literature studies”. Patchwork Girl’s relevance can be attributed to a number of factors. Foremost is its relationship to Frankenstein, perhaps the most well-known work of (science) fiction. Even those unfamiliar with Mary Shelley’s masterpiece recognise some of its basic premises and, even more probably, its monster. Additionally, Patchwork Girl has been saved from the technological advances that doom most hardware-specific literary objects. It is a shapeshifting monster, having changed physical and technological form a number of times. It was written on and is housed in Eastgate Systems’ proprietary Storyspace software and was first available as a floppy disk, then via CD-ROM, then on a USB drive, and in recent years as an online download. Patchwork Girl’s resistance to obsolescence can also be attributed in part to demand: Jackson’s novel is a pillar in electronic literature generally and certainly one of the best-known and well-studied artifacts of first-generation electronic media. Finally, Patchwork Girl remains relevant because it is in many ways a meta-feminist text. It is often given a feminist reading when its content is considered: among others, Laura Shackelford reads it as “the resistance of a dynamic, multiple category of the feminine” (Citation2006, p. 94); and Marie Mulvey-Roberts argues that “[i]n Patchwork Girl, Jackson radicalises perceptions of the traditional female role” (Citation2014, p. 85). It is not far-fetched to say that it may be impossible to read Jackson’s novel as anything but feminist. And all by design. This is not an exhaustive list, but it certainly demonstrates why Patchwork Girl remains an esteemed literary hypertext—a particularly fantastic achievement seeing as hypertext has been dead for over twenty years.

Markku Eskelinen declared hypertext dead in 1999, and Nick Montfort—well-known scholar and creator of electronic literature—concurred and called time of death in his 2000 article, “Cybertext Killed the Hypertext Star”. Montfort’s declaration was in part a response to Espen Aarseth’s attempts to shift literary scholarship toward cybertext. After all, Aarseth set out to “try to construct a model of textual communication that will accommodate any type of text” (Citation1997, p. 18). Cybertext obviously went on to be influential, but in many ways this formulation of dichotomy or tension between cybertext and hypertext ultimately ends up with cybertext existing as an expansion of hypertext (or, better, perhaps, a hypertextualization of everything). Aarseth was interested in “the cybernetic intercourse between the various part(icipant)s in the textual machine” (p. 22). Said another way, cybertext adds nodes to conceptions of the textual network or experience of the textual network—it expands the conception of text so that text is considered part of a given medium rather than a medium itself. Ergo, cybertext, as super-hypertext (or, again, the hypertextualization of everything), killed hypertext. However, Montfort qualified his concurrence by writing that hypertext is dead only “if we consider hypertext as a category that defines a special, valid space for authorship and criticism of computerized works of writing” (2000). That is quite the specific body to be throwing in the proverbial grave, which makes the caveat he added to his original proclamation of particular import: “The hypertext corpus has been produced; if it is to be resurrected, it will only be as part of a patchwork that includes other types of literary machines” (para. 1). The hypertext corpus Montfort is referring to seems to encompass mostly what Dene Grigar dubbed “the Eastgate School” (O’Sullivan, Citation2019, p. 55), because Eastgate’s collection “establishes an identity for an important aspect of the field, with anchor points that enable thoughtful comparisons and evaluations of work” (Heckman & O’Sullivan, Citation2018). Although hypertexts were certainly being created using other programmes, the majority of what other scholars have defined as “canonical” hypertexts always include and usually feature Eastgate’s Storyspace compositions.

Taking these early and “canonical” works that dominate electronic literature as the corpus Montfort was referring to when he declared hypertext dead corroborates his and Eskelinen’s assertions. Storyspace hypertext—this bracketed-off, software-specific form of embodied hypertext—fell out of popularity relatively quickly, and, as a literary medium was dead by the turn of the century. That being said, Montfort left the casket open with the second half of his assertion, which offers that caveat to the death of hypertext: “if it is to be resurrected, it will only be as part of a patchwork that includes other types of literary machines” (Citation2000, emphases mine). At first glance, this caveat seems trite—after all, it is the fate of all technologies to be doomed to obscurity unless another machine (or amalgamation of machines) is used to generate backward compatibility for that technology—but Montfort’s caveat is extremely adroit, and not just because of his clever use of the word “patchwork”. Montfort is open to the idea of resurrection, and there is certainly a conveyor belt of new literary machines that can be used for reanimating the literary medium of hypertext, principal among which is currently Twine, the “open-source tool for telling interactive, nonlinear stories” (Citation2003) that Salter and Moulthrop describe as capable of making “pretty much any genre of interactive text the user envisions” (Citation2021, Chapter T-1). My overarching argument in this article is that the resurrections of Storyspace hypertext and the various iterations of hypertext still in use today should be considered undead hypertext and, by extension, undead electronic literature. The zombie-in-chief of this undead electronic literature is, fittingly, Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl, which transgresses electronic literature historiography by continually being resurrected by scholars (including the author) and put to use as its own entity rather than as cog in some other literary machine. And since Patchwork Girl cannot be dead, Jackson’s novel is uniquely poised to embody the newest waves of intersectional digital humanities scholarship of the moment. In order to demonstrate Patchwork Girl’s power as undead electronic literary artifact, this article resurrects it yet again in order to subject it to a close reading using two lenses—intersectionality and multiplicity—currently at work in digital humanities scholarship. As an undead electronic literary medium, hypertext remains a weapon in feminism’s arsenal, capable of containing, mapping, and reifying (among others) multiple internal and contextual multiplicities. To paraphrase Odin (Citation2010), it continually reinscribes the monstrous self (71), and this article takes that continuity is proof of life. Hypertext is dead; long live hypertext.

Patchwork Girl as a feminist (hyper)text

Shelley’s Frankenstein has been read as a feminist text for decades, and, although it will likely match its namesake for volume, Jackson’s Patchwork Girl has also been taken up by scholars utilising feminist and gender-related lenses.Footnote1 Rather than tracing an exhaustive chronological history that includes every feminist critique of Jackson’s work, I will now spend a few moments playing Victor Frankenstein by stitching together a few of the more prominent examples. When laying out ideas for their “applied e-lit” approach in 2020, Ensslin et al. identified Patchwork Girl as an example of the “most canonical way of writing women’s bodies in e-lit” wherein the idea of the fragment “eludes the reader-player as it constantly deconstructs and reconstructs itself in absentia”. They point out that Shelley’s hypertext novel “has frequently been called upon as the perhaps most fitting allegory of poststructuralist thought in digital space as the hypertextual, female monster presents a compelling, cyberfeminist response to the phallocentric ur-story”. Jaishree Odin’s work on gender and performance delineates how Jackson’s allegory “opens Shelley’s text from within and rewrites its innermost core, which is constituted of the female voice struggling to understand both its rejection by its creator and its outcast status as the outsider and the other” (Citation2010, p. 64). By so doing,

the text exfoliates outward and makes difference and multiplicity the basis of identity and politics … The representation of the female artistic subjectivity as monstrous becomes synonymous with the expression of difference that refuses to disguise itself or be suppressed by the male tradition. (p. 64)

Marie Mulvey-Roberts refers to Patchwork Girl (the character) as “Jackson’s Everywoman” and discusses an instance in the text in which Patchwork Girl makes use of contemporary technology to become her own surgeon and explore her individual parts. By so doing, Patchwork Girl gazes upon the “prohibited text” of an open female body, which Mulvey-Roberts deftly connects to corporeal liberation “made possible through writing and the ‘disembodied realm’ of cyberspace” (Citation2014, p. 85). Mulvey-Roberts frames Patchwork Girl as one of the many conceptual “brides” of Frankenstein, and by so doing demonstrates the complicated relationship between Patchwork Girl and Frankenstein and the separation that exists between their respective monsters. Their hybridity

can be read as embodying the inter-textuality of Shelley’s novel. Indeed, the yellow skin of the male monster resembles the yellowing pages of an old book. By way of contrast, Shelley’s female creation is an unwritten page. We never enter into her subjectivity. (p. 86)

“This female monster stands at the intersection of being and non-being, life and death, the human and the non-human” (p. 92). And like its titular monster, Patchwork Girl stands at various intersections—generic and technological being most readily visible—making both hypertext and protagonist personifications of multiplicity, which Linstead and Pullen define in relation to feminist thinking as “not a pluralized notion of identity but an ever-changing, non-totalizable collectivity, an assemblage defined, not by its abiding identity or principle of sameness over time, but through its capacity to undergo permutations and transformations” (Citation2006, p. 1296). This capacity for permutation and transformation is responsible for more than a little of Patchwork Girl’s resilience, and Patchwork Girl lives up to the billing. It can hardly be said either is dead.

Containing multitudes: Patchwork Girl as inclusionary universal subject

Because it lies at the intersections of digital humanities and electronic literature (among other monstrosities), Patchwork Girl is well-positioned to both acknowledge and forward emerging feminist scholarship in these areas. This article focuses in particular on Roopika Risam’s work in digital humanities. Risam’s intersectional-from-the-ground-up approach to scholarship advocates for intersectional practices that take difference into account from the beginning and that integrate both theory and method:

At the juncture of the two, we must attend to discourses and histories of race and racialization, complexities of gender, complications of class, the operations of sexuality, and their intersections. In doing so, we can create projects that engage, rather than rebuff, difference. (Citation2019, p. 31)

In order to be an inclusionary universal subject, Patchwork Girl has to be able to represent anyone and everyone—she must be multiplicity incarnate. Kim Gallon’s work on Black digital humanities offers an example of intersectional multiplicity (to use a slightly redundant term) which is most excellent. Gallon “names the ‘black digital humanities’ as the intersection between Black studies and digital humanities, transforming the concept into corporeal reality while lending language to the work of the black digerati in and outside of the academy” (Citation2016, p. 43). Gallon is not interested in simply sewing an appendage on to digital humanities; she is looking to build a whole new body. This is an intricate undertaking, made possible in part by Gallon’s conceptualisation of Black digital humanities as “less an actual ‘thing’ and more of a constructed space” for considering the sutured intersections that exist between the entities it is comprised of. She invites us to make space for multiplicity and examine the interstices of any and all things that fill that space. Multiplicity is not a result of (Black) digital humanities—it is the whole point. Gallon’s Black digital humanities views humanity itself as an evolving category, which renders the digital more corporeal and contextual. The individual pieces interact with and inform each other in ways that blur the boundaries between them. Navigating the interstices of this captivating monster, Gallon’s work reaches back to consider the “original” humanities as well as digital humanities, allowing her to generate something new (Black digital humanities) without sacrificing the current (digital humanities) or the past (original humanities). That makes for a lot of pieces—a mountain of multiplicity—and Gallon, like Risam, encourages us to embrace any and all hybridity, plurality, contradiction, and tension (Citation2018, p. 84) that comes along with it. And Gallon’s conception of a multiplicitous digital humanities is not the only one. According to FemTechNet, multiplicity—which they refer to as “mess”—“serves as a theoretical intervention in popular notions of digital media as neat, clean, and hyper-rational” (Losh et al., Citation2016, p. 94) and foregrounds the need for “a willingness to hold sometimes competing paradigms and goals together in a single project, despite the existence of tensions around risk, privilege, expertise, ownership, and appropriation” in contemporary research (p. 97). The mess(es) FemTechNet are interested in are manifestations of Gallon’s multiplicity, and all this multiplicity makes for a lot of suturing, with suturing being itself an elastic exercise. Johndan Johnson-Eilola situates suture as a partial connection and one that “never operates to bind a subject completely to a single position” (Citation1993, p. 89), a conception that works well in relation to Patchwork Girl, where multiplicity is the point and appendages abound. As Van Looy and Baetens argued, Patchwork Girl endeavours to “create the girl's body and by extension her identity by piecing together textual components that at the same time create the physical but also the conceptual entity of the text itself”, which in turn “enables, as in Deleuze and Guattari's model of subjectivity, the representation of the focus of manifold threads of meaning that bind together to form individual identity” (Citation2003, p. 16). In like manner, close reading Jackson’s hypertext novel allows us to examine the multiplicity that both Patchwork Girl and Patchwork Girl embody. This will generate both a physical and conceptual identity of Patchwork Girl and the literal intersectionality that makes her an inclusionary universal subject—one whose reach extends well beyond the text.

Close reading Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl

Close reading Patchwork Girl is a complicated undertaking. The overarching story is relatively straightforward—as Jaya Sarkar explains it,

In Patchwork Girl, Victor Frankenstein’s aborted second creation, the female monster, whom he violently tears up mid-construction, is sewn up by the author Mary Shelley herself and then she engages in a love affair with her creation, before the monster sets out for America to start her own life. (Citation2020, p. 2)

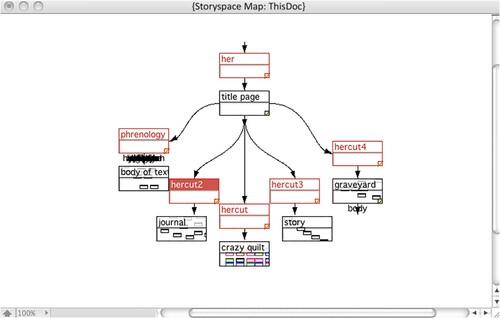

Additionally, rather than moving through the hypertext multiple times, I have made use of the built-in Storyspace Map in order to see and pre-emptively navigate (or not navigate) the various loops of “lexia” in the journal branch. Lexia is “a term used by Roland Barthes (1974) to define blocks of text, or ‘units of reading’ [that was] later expanded by George P. Landow to include other forms of media: ‘blocks of words, moving or static images, or sounds’” (King, Citation2009, p. 2). Lexia is

commonly used when discussing hypertext fiction to describe a discrete block of text. In Patchwork Girl, each lexia [appears on] the screen, like a page, and is replaced by a new lexia when the reader clicks on certain words or phrases (Hackman, Citation2011, p. 86)

Together, the link and the lexia – the ‘skin and bones’ of a hypertext system – provide a story for the reader to explore. One can travel through this system, reading the lexias and clicking on links, to piece together the monster's story as well as her body. The relationship between the body and the written word is emphasized in this approach to story-telling … With lexias representing the monster's body parts, and hyperlinks the seams of their connections, the network operates as a pluralistic group of systems: a body. Form and content become inseparable. (Citation2009, p. 2)

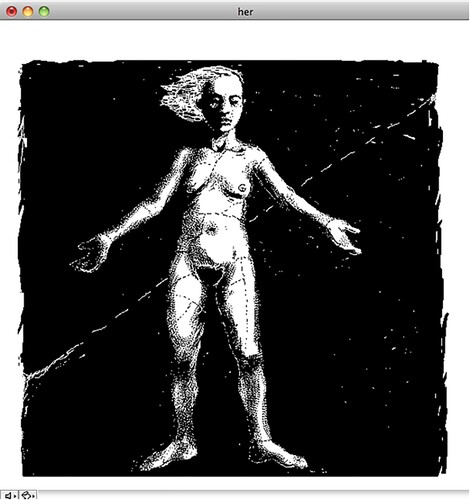

My slightly-cheated close reading here is a representation of what I call an interactive close reading, which mirrors King’s notion of form-and-content inseparability by weaving together three separate close readings: (1) a visual reading, (2) an experiential reading, and (3) a literary reading. The visual reading will offer descriptions of what is on the screen as the reader navigates through the text. Electronic literature is many times closely connected to, and often entirely dependent on, its connection to the visual, so a close reading of an electronic literature artifact, especially a hypertext novel, would be incomplete without time spent analysing its visual elements. As Anne Wysocki put it, “When you first look at a page or screen, you initially understand its functions and purposes because it follows the visual conventions of a genre” (Citation2003, p. 124), and since Patchwork Girl falls under the “hypertext novel” genre, it and the specific visual elements of Eastgate’s Storyspace software it is comprised of merit examination in my interactive close reading. The main visual elements of Patchwork Girl are images that appear inside their own lexias. The visual reading of these images will overlap with the experiential reading because readers are required to interact with the images as they would any other lexia in order to make their way through the story (or a version of the story, at least, since I will not be examining every single lexia). That being said, my skip-stuff cheat code has resulted in the jettisoning of almost all non-textual visual representation, so this article’s visual close reading will suffer for lack of representation this time around. The experiential reading will almost always refer to the Storyspace Map in some way, as each lexia has a title at the top of it that is represented on the Storyspace Map (when referring to them throughout my reading, each lexia’s title will be in curly brackets {like this}) ().

On some MacBooks, like the old MacBook 3 I use to access Patchwork Girl, the lexias do not fill the screen, which means the Storyspace Map is at least partially visible while reading. In my experience, this is sometimes distracting and sometimes extremely helpful, but it is important to highlight the experiential reading as its own entity if for no other reason than that hypertext interaction is a part of the Patchwork Girl experience that non-electronic texts can imitate to a degree but not replicate entirely. Just as the visual and experiential readings are intertwined, it is essentially impossible to perform either of them or a hybrid of the two without veering into the literary thread in this interactive close reading. The literary reading brings the plot into the picture, and Patchwork Girl is especially reliant on narrative because it is an early hypertext and one that owes much of its existence to (and cannot escape) a famous literary work. The literary reading will weave together the individual pieces of Patchwork Girl—such is the nature of stories—but in this case it will also suture itself onto the various visual and experiential elements that bring this particular text to life.

Interactive close reading: multiplying multiplicity at the end of the journal loop

Nearing the end of the journal branch, the reader moves from the {crave} lexia into a narrative loop titled scars that contains nine lexias and in which the unnamed author(s) of the journal recounts a night of intimacy with Patchwork Girl. The scars loop is visible on the Storyspace Map as part of the journal, but it is visually freestanding and disconnected. As presaged by its title, most of the scars loop’s narrative is focused on the monster’s body. In {I moved} her face and hands are

criss-crossed by the traces of innumerable tucks and gathers and the tiny white flecks where the careful, even stitches had been removed in her monstrous infancy. But long cords of curdled, whitened tissue divided her torso into sectors as distinct as patches in a quilt.

Coming out of the scars loop, the reader is deposited into the {female trouble} lexia. Like the scars loop, {female trouble} is visible on the Storyspace Map but disconnected, slightly more so, in fact, and its text is only accessible if the reader moves all the way through the scars loop. The very first word of {female trouble} is a man’s name—Percy. At first glance, the mention of Percy pulls the reader out of the narrative a bit and reminds them how nebulously constructed Patchwork Girl’s narrative is, but having moved from the {her, me} lexia into one where everything is defined in relation to Percy is also a reminder that despite their authority the writer(s) of this journal remain beholden to patriarchal structures. The narrator is beginning to push against Percy in this lexia and setting the stage for a rebellion in coming lexias. She gets him to withdraw, leaving her

growling and hitting the pretty pillows the maid plumps up every quarter hour, by my fretful calculation, and with such a bland and optimistic demeanor that I long to bite and tear at her pillows and greet her calmly in a blizzard of feathers with quills between my teeth!

I wish I had her strong limbs; I would run up these Alps, as she tells me she does, following the changing light across fields of ice. How quickly now our positions reverse and teacher turns pupil! She has seen things I will never see; she remembers more than I will experience in my whole life.

a crazy wish! I wish that I had cut off a part of me, something Percy would not miss, but something dear to me, and given it to be a part of her. I would live on in her, and she would know me as I know myself.

Clicking this link takes us to a new lexia titled {mary}, and Patchwork Girl is once again the narrator. Interestingly, at this point the reader is off the (Storyspace) map. The Storyspace Map shows that {mary} is the first lexia in a loop titled severance, but severance does not seem to appear anywhere else on the Storyspace Map. The scars loop and {female trouble} lexia were both visibly separated from the other lexias on the map, but outside of the path I have moved through in this portion of the closer reading there are no clues as to the existence of the severance loop. (If there are, I have been entirely unable to find any.) The {mary} lexia is written by Patchwork Girl and describes her departure. She is headed for America—was headed, actually, as it seems some time has passed. Despite the intimacy so recently described in the preceding lexia, the monster says things like “Mary and I both wished me gone” and that both of them are “far from sentimental”. But at the end of {mary} the reader learns that Patchwork Girl also has a secret: “The day I left Mary forever, we performed a certain surgery”. Again requiring the reader to find a specific passage in order to link to the next lexia, only “a certain surgery” is clickable. It leads to the {surgery} lexia, where Patchwork Girl’s secret turns out to be the fulfilling of the journal writer’s crazy wish to have a patch of her own skin added to Patchwork Girl. The next lexia, {join}, gives the description of the surgery during which farthing-sized circles are cut from Mary’s calf skin and the scar tissue between Patchwork Girl’s thigh and groin, switched, and sewn back into place. Both of them are selective in where they cut from:

We had decided that as my skin did not, strictly speaking, belong to me, the nearest thing to a bit of my flesh would be this scar, a place where disparate things joined in a way that was my own. For her part, she chose a piece of skin Percy would likely never miss, in a place where bandages could be readily explained if they should be discovered.

The {us} lexia branches, and because it appears to be one giant link the reader is most likely to click somewhere inside the lexia and be taken to {aftermath}, in which Patchwork Girl mourns Mary as both mother and lover, successfully arrives in America, and starts on the next leg of her journey (no pun intended). However, if the reader clicks those last five words, “my story, which is ours”, they are taken to a lexia titled {hideous progeny}. The font has changed, and readers who are quite familiar with Frankenstein will recognise the four sentences contained in this lexia as an excerpt from Mary Shelley’s (real life Mary Shelley’s) Citation1831 introduction to Frankenstein (itself an amalgamation having been heavily influenced and edited by real life Percy). But knowing precisely where the words are from does not diminish their fluidity. Quite the opposite, in fact. As it is a direct quote from Frankenstein, its inclusion becomes automatically hybrid because it owes its existence in the hypertext novel to more than one of the authors listed in the title page’s segmented author line, which, by way of reminder, reads “By Mary/Shelley, & Herself”. This both blurs the distinctions between the possible authors and opens the door for multiple possible interpretations of the {hideous progeny} lexia. It starts, “And now, once again, I bid my hideous progeny go forth and prosper”, which seems to be Mary and/or the journal writer speaking about Patchwork Girl’s departure—a reading that could be reinforced by {aftermath} which would have opened the branch not chosen. But then, starting in the third sentence, it reads, “Its several pages speak of many a walk, many a drive, and many a conversation, when I was not alone; and my companion was one who, in this world, I shall never see more”. This could be hearkening back to the blurring(s) together of real and fictional that happened in the first choice in the novel when the reader chose between {written} and {sewn}, but it could also be referring to the journal branch, the Gillman-esque blurring together of women characters, and/or Patchwork Girl generally, among others. Upon clicking on the words “hideous progeny” and moving into the {why hideous?} lexia, the ambiguity continues and even heightens. Though it sounds a bit like Patchwork Girl is at the helm again, {why hideous?} is compact and ambiguous. It reads, in its entirety,

I’ve learned to wonder: why am I ‘hideous’? They tell me each of my parts is beautiful and I know that all are strong. Every part of me is human and proportional to the whole. Yet I am a monster because I am multiple, and because I am mixed, mestizo, mongrel.

Patchwork Girl and/as undead electronic literature

The word “multiple” in {why hideous?} can be clicked and followed through a few lexia in a loop titled mixed up, but that move is actually a huge jump to the broken accents branch (the last item on the title page’s branch list), so I will end my examination of Patchwork Girl with the final three words of the {why hideous?} lexia. These final three words—mixed, mestizo, mongrel—are a fitting end to a reading of Jackson’s novel, as they remind yet again that Patchwork Girl contains a massive mess of possibilities. Through this interactive close reading, I have demonstrated how Jackson’s novel embodies multiplicity and how that multiplicity is rendered most visible in (and through) Patchwork Girl herself. For starters, Patchwork Girl literally lives up to her name: her body is an amalgamation of other women’s bodies, which is not to say that those pieces are unified into a single whole. Each of her pieces retains its original personality—its original consciousness, even—thereby making Patchwork Girl, to use Marie Mulvey-Roberts’ term again, the Everywoman. And as the Everywoman, she is able to take on the role of inclusionary universal subject, or multiplicity incarnate as I put it previously, which makes her a prototype of the type of character capable of dismantling the restrictive notions of the exclusionary universal subject that Roopika Risam adeptly identifies as taking up too much space in our minds to this day. And Patchwork Girl’s work is enhanced by Patchwork Girl’s form. In addition to delineating the character’s multiplicity inside the novel, my interactive close reading has also demonstrated how Patchwork Girl embodies multiplicity through its form. Like Patchwork Girl, Patchwork Girl is a conglomerate monster. It is a hypertext novel, which means readers are free to move through it in the order of their choosing, unbeholden to one way of seeing. By offering agency to its reader(s) Patchwork Girl tells more than one story, so, like its titular character, Patchwork Girl is never one single thing. It is not just a novel but also a hypertext, and it cannot be just a hypertext either because it is also a novel. It is, by design, a flexible, multiplicitous text that refuses to offer a straight answer, let alone a full picture.

That refusal is what makes Patchwork Girl interesting and what keeps it undead. It is continually being raised from the hypertextual dead, and every time that happens its titular character is very slightly changed by virtue of the new perspectives she is called on to incorporate into herself. Such is the nature of electronic literature, by which I mean all electronic literature is undead in this way: when we access it, we interact with something that is by default a(n often monstrous) conglomeration, and we add our contemporary ways of seeing to its history. Multiplicity is part and parcel of electronic literature. Yes, it is reliant on both the computer and its user—it is read both electronically and bodily—but, in Patchwork Girl’s case, at least, it can stay undead as long as there is someone there to open the proverbial grave. And even the importance of doing so is multifaceted. As Carolyn Guertin lamented, “feminist theory and those early documents and works by women writers quickly obsolesce on the spaces of the web, and are too easily forgotten or ignored by critics. Memory is short in cyberspace” (Citation2021, p. 85), but Jackson’s Everywoman has yet to find someone she cannot absorb. Call it dead all you want; hypertext is very much alive in Patchwork Girl as I have demonstrated by resurrecting it for this article. Eastgate Systems have ensured that this flagship hypertext remains accessible. I purchased my copy at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Eastgate Systems emailed me a link through which I could download it, which included a pass phrase to unlock the disk image once I had done so. This unlocking gave me access to the Storyspace Reader software (that is added to the Applications folder) and Patchwork Girl (which can be copied to any convenient folder). Eastgate also made sure to specify that the hypertext is DRM-free so I would know it can be used in the same ways one would use a paper book. This was all surprisingly easy, especially because I had previously heard that Patchwork Girl only worked on older Mac computers, so I dug out a 2007 MacBook “Core 2 Duo” 2.2, or “MacBook3,1”, in order to perform my resurrection/analysis. I have since learned that Eastgate keeps updates the software every few years to keep up with macOS developments, including a brand-new edition for the latest macOS, thereby facilitating future resurrections of Patchwork Girl and (un)dead hypertext. In this article, I have resurrected Patchwork Girl in order to stitch not just intersectional feminist scholarship but intersectional feminist digital humanities scholarship to her. Liu (Citation2012) argued that “the digital humanities are noticeably missing in action on the cultural-critical scene”, and scholars like Risam, Gallon, and FemTechNet, have more than answered his call for dialogue between fields and dialogue between various kinds of people. As the flagship work of undead electronic literature, Patchwork Girl is perfectly positioned to examine the interstices between competing modes of inquiry. And while we remain far from a default inclusionary universal subject, Patchwork Girl is no stranger to making things fit.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 I feel it important to take a moment and demonstrate an awareness of the nuanced nature of feminism and gender-related issues and scholarship. Seeing as Jackson published the novel in the 1990s and scholars continue analyzing it to this day, it goes without saying that Patchwork Girl’s existence spans a huge swathe of societal and academic understandings of gender, many of which are currently emerging and/or in flux. I will spend some time in this article describing and employing intersectional approaches to feminism, a focal point I chose because intersectionality takes into account multiple, varied aspects of identity (and, by so doing, becomes appropriate for a discussion involving Frankenstein and Patchwork Girl). Despite the many additional contemporary configurations of identity that are not represented here (e.g. womanism, transsexuality, non-binarism), I hope this article will lay the groundwork for expanding the application of these ideas into as many of these conceptions as possible.

References

- Aarseth, E. J. (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives on ergodic literature. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Bell, A. (2010). The possible worlds of hypertext fiction. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ensslin, A., Bailey, K. A., Munro, L., Fowlie, H., Perram, M., Wilks, C., Riley, S., & Rice, C. (2020). ‘These waves … ’ writing new bodies for applied e-literature studies. Electronic Book Review. https://doi.org/10.7273/c26p-0t17

- Gallon, K. (2016). Making a case for the black digital humanities. In M. K. Gold & L. F. Klein (Eds.), Debates in the digital humanities 2016 (pp. 42–49). University of Minnesota Press.

- Guertin, C. (2021). Cyberfeminist literary space: Performing the electronic manifesto. In J. O’Sullivan (Ed.), Electronic literature as digital humanities: Contexts, forms, & practices (pp. 80–91). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Hackman, P. (2011). ‘I am a double agent’: Shelley Jackson's ‘Patchwork Girl’ and the persistence of print in the age of hypertext. Contemporary Literature, 52(1), 84–107. https://doi.org/10.1353/cli.2011.0013

- Heckman, D., & O’Sullivan, J. (2018). Electronic literature: Context and poetics. In K. M. Price & R. Siemens (Eds.), Literary studies in a digital age (pp. 1–28). Modern Language Association.

- Jackson, S. (1995). Patchwork girl; or, a modern monster. Eastgate Systems.

- Johnson-Eilola, J. (1993). Control and the cyborg: Writing and being written in hypertext. Journal of Advanced Composition, 13(2), 381–399.

- Keep, C. (2006). Growing intimate with monsters: Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl and the gothic nature of hypertext. Romanticism on the Net, 41–42.

- King, N. (2009). Hypertext and the postmodern Frankenstein. Media in Transition, 6, 1–15.

- Klimas, C. Twine. www.twinery.org

- Latimer, H. (2011). Reproductive technologies, fetal icons, and genetic freaks: Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl and the limits and possibilities of Donna Haraway’s cyborg. Modern Fiction Studies, 57(2), 318–335. https://doi.org/10.1353/mfs.2011.0051

- Linstead, S., & Pullen, A. (2006). Gender as multiplicity: Desire, displacement, difference and dispersion. Human Relations, 59(9), 1179–1312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726706069772

- Liu, A. (2012). Where is cultural criticism in the digital humanities? In M. K. Gold (Ed.), Debates in the digital humanities 2012 (pp. 490–509). University of Minnesota Press.

- Losh, E., Wernimont, J., Wexler, L., & Wu, H. (2016). Putting the human back into the digital humanities: Feminism, generosity, and mess. In M. K. Gold & L. F. Klein (Eds.), Debates in the digital humanities 2016 (pp. 92–103). University of Minnesota Press.

- Montfort, N. (2000, December 30). Cybertext killed the hypertext star. Electronic Book Review. https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/cybertext-killed-the-hypertext-star/

- Mulvey-Roberts, M. (2014). The after-lives of the bride of Frankenstein: Mary Shelley and Shelley Jackson. In M. Purves (Ed.), Women and gothic (pp. 81–96). Cambridge Scholars.

- Odin, J. K. (2010). Hypertext and the female imaginary. University of Minnesota Press.

- O’Sullivan, J. (2019). Towards a digital poetics: Electronic literature & literary games. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Risam, R. (2018). Decolonizing digital humanities in theory and practice. In J. Sayers (Ed.), The Routledge companion to media studies and digital humanities (pp. 28–86). Routledge.

- Risam, R. (2019). Beyond the margins: Intersectionality and digital humanities. In B. Bordalejo & R. Risam (Eds.), Intersectionality in digital humanities (pp. 13–34). Arc Humanities Press.

- Salter, A., & Moulthrop, S. (2021). Twining: Critical and creative approaches to hypertext narratives. Amherst College Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.12255695

- Sarkar, J. (2020). Reading hypertext as cyborg: The case of Patchwork Girl. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 12(5), 1–7.

- Shackelford, L. (2006). Subject to change: The monstrosity of media in Shelley Jackson's Patchwork Girl; or, a Modern Monster and other posthumanist critiques of the instrumental. Camera Obscura, 21(63), 63–101.

- Shelley, M. (1831). Introduction to “Frankenstein; or, the modern prometheus”. Project Gutenberg. Updated March 13, 2013. https://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/42324/pg42324-images.html.

- Van Looy, J., & Baetens, J. (eds.). (2003). Close Reading new media: Analyzing electronic literature. Leuven University Press.

- Wysocki, A. F. (2003). The multiple media of texts: How onscreen and paper texts incorporqate words, images, and other media. In C. Bazerman & P. Prior (Eds.), What writing does and how it does it: An introduction to analyzing texts and textual practices (pp. 123–163). Routledge.