ABSTRACT

The experience of reading digital comics differs from that of other reading in that it involves the interplay between text and art, both “on the page”, for example, as with the traditional comic book format, or “off the page” in interaction with devices, apps and “extras” the Alt Text in the webcomic, xkcd. This interplay and placement can communicate movement, stillness, suspense, bringing the reader along not only through content or story arc but also through the material affordances, the physical reality of the comic in combination with the technology. The findings of this exploratory study reveal both the varied reading experiences of digital comics as well as the shared experiences of haptic interactions and emotional perception and reaction through the use of devices, comics platforms and apps, and social media. Although webcomics, one type of digital comics, have long been a part of the evolution of hypertext, their place has not always been acknowledged in the scholarship. This research not only contributes towards an empirical, qualitative understanding of reader response to and experience of a range of digital comics including webcomics, but also addresses their role as an example of the haptics of hypertext fiction.

Introduction

The experience of reading webcomics and other types of online comics differs from the outset from that of other reading in that it involves the interplay between text and art. Comics make for distinctive reading, moreover, in the precise placement and juxtaposition of text and art on the page (Groensteen, Citation2007), the multiple-panel layout of the comic book being the most readily recognisable feature and the online infinite canvas being one of the innovation to that feature. All these characteristics give comics that sense of motion and time elapsing (Cohn & Maher, Citation2015). The reader is brought along quickly for action or slowly for more contemplative scenes. In this way, “digital comics are offering readers physically similar experiences to computer games and other digital media (particularly when both media are interacted with on the same device)” (Moura, Citation2014). In comics studies, what constitutes a digital comic (see Dittmar, Citation2012; Goodbrey, Citation2013; Priego, Citation2011; Wilde, Citation2015 among others), and whether it is different from a webcomic, continues to be a matter of debate. In this paper, digital comics include digitised, born-digital, and web-based comics. Accordingly, webcomics are a form or subset of digital comics. We also consider webcomics as part of electronic literature, in the form of digital fiction. We fully acknowledge that this may also be a matter for contention: webcomics have not received much attention in electronic literature scholarship, as some webcomics are to be considered more “born digital” or “digital exclusive” (unable to be remediated satisfactorily to print) than others. However, we follow Mangen’s (Citation2008) example in maintaining that any in-depth consideration of definitions is beyond the scope of this article.

The haptics of touch in reading digital comics, more specifically the experience of touch in the use of devices, is reflective of the haptics involved in hypertext and electronic literature. According to Anne Mangen (Citation2008), “reading is a multi-sensory activity, entailing perceptual, cognitive and motor interactions with whatever is being read” (p.404). In her article about hypertext, haptics, and electronic literature, Mangen observes that reading “[depends] upon the fact that we are both body and mind” (p.404). Webcomics, a form of digital comics and electronic literature, share that same “special emphasis on the vital role of our bodies, and in particular our fingers and hands, for the immersive fiction reading experience” (p. 404). According to our exploratory research, the (im)materiality (Mangen, Citation2008) of the webcomic itself and the unquestionable materiality of the devices with which to read them arguably create a more intense multi-sensory experience than in other types of digital or electronic works. Because of these differences in experience, comics reading has the “potential to enrich our exploration of reading in our currently saturated media landscape” (Serantes, Citation2019, p. 7).

Digital comics, including webcomics, graphic novel ebooks, and comic book apps, have all these characteristics, along with some singular affordances that make the reading experience a uniquely digital one. In this paper, we will present findings from an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)-funded digital comics reading experience project, where we used Human–Computer Interaction (HCI), specifically User Experience (UX), methods to gather and analyse qualitative data collected from British Library readers. The findings of this exploratory study reveal both a varied reading experience of digital comics, including webcomics and comics reading apps, as well as the shared experiences of haptic interactions and emotional perception and reaction through the use of devices, comics platforms and apps, and social media. This research contributes towards an empirical, qualitative understanding of reader response to and experience of a range of digital comics including webcomics, thus addressing a gap in comics studies and electronic fiction scholarship. In doing so, it highlights digital comics as an example of the haptics of hypertext fiction. Moreover, it situates digital comics within a broader digital tradition and, in doing so, highlights their importance as a unique and engaging form of fiction.

This research

In 2022, as part of AHRC Additional Student Development funding, we undertook online comics research, utilising HCI, and specifically UX, methods that focus on understanding interaction. The literature indicated that there had not been a tradition of this kind of research, nor of digital and webcomics readers in general (see Literature Review below). Therefore, it was considered not only important to conduct researcher-led semi-structured interviews with digital comics readers but also to have reader-led think alouds (Iterative Talk Aloud or ITA) where readers talked the researcher through the comics they read online and the platforms, apps and devices they used. By reading along with research participants, sharing the comics they actually read online as well as their experiences of doing so, we were able to observe first-hand that the reading of digital comics can be just as immersive as print reading, and that the materiality of the reading devices often added to that experience. This HCI approach demonstrates the lead this discipline has taken in psychological ergonomics and materiality, especially in the area of digital devices. (Hillesund et al., Citation2022; Mangen, Citation2008; Mangen & van der Weel, Citation2016)

This exploratory reader study, conducted with the British Library and HCID City, University of London, was designed with two primary aims:

to learn about the experiences of digital comics readers, their responses to comics online, the devices and platforms that contribute to the experience,

to elicit non-academic reader feedback for the UK Web Comic Archive and to provide some recommendations for the shaping of the Archive from a usability and content perspective.

This paper covers those findings that deal specifically with the first of these aims (an account of the second can be found in Berube et al., Citation2023), responding to the following research questions which are addressed in this paper:

How do readers find and read comics online? Are there preferred portals, apps, social media for reading, discovering?

What is the experience of readers accessing and reading comics through platforms like Webtoon (Citationn.d.) (comics app for smartphones), Comixology (Citationn.d.) (formerly a comics publishing platform, now part of Amazon), Marvel Unlimited (Citationn.d.) (Marvel comics platform), etc., as well as social media?

(2a) How easy is it to find comics they like on the platforms? What do platforms do that is helpful, not helpful?

Literature review

This study demonstrates that “comics have always been hypertextual … comics have always existed within networks of texts, images, and other media” (Benatti et al., Citation2023). Essentially, the history of the web is the history of webcomics (Kleefeld, Citation2020). It is a form that continuously looking for expression through the web and any new development on the web. Therefore, it should not come as a surprise that webcomics were using hypertext almost from the very beginning of the concept (Benatti et al., Citation2023, referring to Ted Nelson “in 1974 [coining] the term ‘hyper-comics’”), with examples such as Andrew Hussie (Citationn.d.) in Homestuck and Daniele Lieske (Citationn.d.) in The Wormworld Saga () (see also Priego, Citation2012, for a consideration of other earlier examples of the form). It can be argued that historically print comics also experimented with a print version of hypertext, just as much influenced by gaming, graphic adventure games and ludic elements of the digital form, for example, Building Stories (which also included a digital app). According to Benatti et al. (Citation2023), hypertext is one of the most recent “transformations of the comics medium” that “[promotes] interactions between authors, readers and publishers” (p.2) (see also Antonini et al., Citation2020). Moreover, just as “empirical studies are essential for human–computer interaction (HCI) research and interaction design” (Voit et al., Citation2019, p. 1), we would maintain that they are also essential for understanding the reading experience of digital comics. Because of the inter-relation between the (im)material digital comics text and the materiality of the devices used in their reading, as well as the “design” elements of comics including art and panels, HCI methods of qualitative research provide the best way of understanding the reading experience.

Figure 1. The Wormworld Saga by Daniel Lieske. Retrieved from https://wormworldsaga.com/about.php. The Wormworld Saga is a webcomic and graphic novel, employing the continuous scroll or infinite canvas.

In addition to the haptic and immersive reading experiences that comics and hypertext fiction (or comics as hypertext fiction) have in common, there is also a gap in empirical research into these reading experiences. Mangan observed in 2008 that most empirical research in the reading of hypertext fiction concerns itself with “perceptual and cognitive aspects of digital reading” (p404). By the same token, most empirical studies of comic readers focus on cognition (Cohn, Citation2013) and the visually perceptual (eye-tracking), as well as involve the use of comics in an applied way through education, health, instructional, in other words not for leisure or fictional works (Priego & Farthing, Citation2020, for example).

According to Mangen and van der Weel (Citation2016), not much has changed in empirical research of hypertext fiction a decade on:

compared with the vast number of studies on cognitive aspects of reading (e.g. reading comprehension and metacognition) and the wealth of experimental research using textoids to examine low-level perceptual and linguistic processing, there is a scarcity of empirical research on typical pleasure reading of different genres of literary text (p. 170).

However, other scholars would maintain that there has been a

a third wave of hypertext and DF scholarship in which empirical reader response studies are combined with stylistics analyses to develop an understanding of how readers process, for example, DF’s narrative structures and literary meanings. (van der Bom et al., Citation2021)

While hypertext can provide a distraction, especially in the reading of fiction (see Findings below), empirical research as demonstrated by van der Bom et al. (Citation2021) illustrates that reader control over links can enhance the reading experience. What is significant is the understanding of how the reader processes the links in relation to the text, and that empirical studies provide that understanding.

This exploratory empirical research, conducted to understand the experience of reading digital comics and specifically webcomics from the leisure reader’s perspective, fills a gap in comics studies’ literature (Woo, Citation2020). There has been a tradition of theoretical scholarship in comics, some of it involving reading: for example, on comics as literature (Chute, Citation2008), as part of fan studies (Lamerichs, Citation2020; Woo, Citation2012), and even on the materiality and mediality of comics (Hague, Citation2014; Priego, Citation2010; Thon & Wilde, Citation2016).

However, there is no real tradition of empirical studies of digital comics readers. Scholars, such as Brown (Citation1997, Citation2009) and Cedeira Serantes (Citation2014, Citation2019), have conducted ethnographic studies into readers mostly (but not exclusively) of print, while Murray (Citation2012) surveyed webcomics readers eliciting qualitative feedback for an article about the “future of comics publishing”. As indicated above, Cohn (Citation2013) considered the order in which readers read comic panels. Royer et al. (Citation2011) reviewed the reading practices of American comics readers in print and digital formats, albeit without empirical research. Applied comics research often works with specific categories of readers in such areas as literacy or health (see, for example, Priego & Farthing, Citation2020) or in connection to the reading practices of young people (Serantes, Citation2014, Citation2019).

It has to be said that not much of this research has applied exclusively to digital comics. More qualitative empirical research from the readers’ perspective is needed, not just to understand the digital comics reading experience, but the experience of the reader in the digital environment, encompassing devices, platforms, and physical and emotional interaction with the text. More recently, readers have been considered in research applying UX and HCI methods, from more quantitative perspectives (Ha & Kim, Citation2016) and specifically with the use of eye-tracking software and teen readers (Arai & Mardiyanto, Citation2011; Zhao & Mahrt, Citation2018). These considerations of the material aspects of digital comics, “the sum of an artifact’s physical and signifying characteristics” (Brown, Citation2018), is an important part of a reader’s experience with a digital comic but excludes the emotional, sensory reaction not just to the content but to this physical interaction. Hague (Citation2014) analyses “the five Aristotelian senses: sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste” (p.4) of interacting with a comic but because it is a theoretical consideration, there is no empirical data on how these senses work to create an emotional response from the reader’s perspective.

While this study is part of a research landscape that includes the use of HCI, specifically UX, methods to examine digital comics, it approaches it from a qualitative perspective that emphasises the “diversity with regards to reading experiences and practices with comics and thus potential variability in the comics reading experience” (Serantes, Citation2019, p. 19). It is a critical addition to electronic fiction and comic studies scholarship, not only because it addresses gaps in both, but also it demonstrates the immersive and haptic nature of reading digital comics.

Research methodology and methods

This user-centred research employs reader-response theory as a way of framing methods and findings, not only analysing how digital comics readers in the study interacted with content but also the digital technology-the “containers” (Kashtan, Citation2018)-for that content. Louise Rosenblatt (Citation1982) describes a type of reader response where reading is a transaction that involves “a reader and a text at a particular time under particular circumstances” (Citation1982, p. 268). Serantes (Citation2014) maintains, however, that most subsequent considerations of transactional reader-response focus on the first part of Rosenblatt’s statement, “reader and text” interaction, and not on the second, “a particular time under particular circumstances” (p. 297). To encompass both aspects of Rosenblatt’s definition, we adopted two research methods: semi-structured interview and contextual observation, especially Iterative Think Aloud (ITA), where the participants took the researcher through their reading practices, what they read, how they read it, and where they read it. Because this was a short-term exploratory study, the focus was very much on the reader, text, and immediate environment and not on the wider sociocultural context involved in extended ethnographic research. However, the use of contextual observation, specifically through ITA, provided an opportunity to collect rich, detailed data (O’Brien & Wilson, Citation2023) that provided insight into the digital comics reading experience. For example, whereas the interviews were “researcher-led”, the contextual observation, in the form of the ITA, was reader-led: readers talked the researchers through their experience of reading, including gestures and expressions to communicate a response. The combination of semi-structured interviews and ITA resulted in researchers and readers together discussing and interpreting reading responses. In this sense, readers tell their own stories or their own versions of comics’ stories.

The interview and observation sessions took place remotely. While it is customary for these types of sessions to be held face to face, preferably in a lab or in-situ, pandemic and resource restrictions dictated the researcher meeting with participants remotely. Regardless of this limitation, this approach was successful because it allowed participants to engage from their own home environments with their own devices, resulting in depth and range in the type of data that was collected.

This remote approach conducted with readers in their natural settings, their own homes or offices using their own devices, allowed us to understand “the context of use” or the actual conditions where reading would take place (Voit et al., Citation2019, pp. 2-3). Although it is true that distraction can occur in the home or in-situ environment, the researcher ensured that attention was always focused. Indeed, while there was no attempt made at emotion elicitation in the study, readers were comfortable enough in their own environment to reproduce their reading experiences, in some cases almost exactly (Larradet et al., Citation2020). A natural setting also meant participants were using their own devices, which made it easier for them to display the digital comics they actually interacted with, on the platforms they actually used.

Recruitment

The focus of this research was not only to understand the reading experience of digital comics readers but specifically of British Library readers who may include digital comics as part of their leisure reading. Because of the limited timescale of six months for the research and the intention to recruit British Library users, a broad or maximum value approach to sampling, over social media for example, was not considered. What was required was a quick means of sampling, almost akin to snowball sampling, where volunteers had already been identified by the main stakeholder, in this case, The British Library. The British Library Reader and Non-User Research report (Butler, Citation2021) addressed this requirement as not only had a dataset of users categorised by research areas been collected, but the research participants had also indicated their willingness to be consulted for future research.

There was the complication that none of these volunteers had expressed an interest in comics in their survey responses (they had been asked to describe their research interests). However, we felt it was worth trying to reach out to a subset of this dataset in the first instance, with the aim of gathering a small sample for the purpose of an exploratory study. Emails were sent out to those who had expressed an interest in humanities, arts, and graphics. Fairly quickly, there were seven responses articulating a strong interest in comics, out of which five were recruited for an interview and iterative think aloud (ITA) sessions. The five study participants, all digital comic readers (DCRs), are referred to in this paper as DCR1, DCR2, DCR3, DCR4 and DCR5.

There is precedent for the small numbers of participants, especially in HCI. According to Makri et al. (Citation2019), “exploratory studies of this nature are suited to small participant numbers, and frequently seen in Human Information Interaction literature” (p.10). The objective of this research was not to generalise findings, but to uncover issues indicative of further research.

The research presents issues raised by readers on the perceptions of digital comics, including webcomics, and leisure reading practices that serve to encourage more in-depth qualitative, empirical research. In addition, it contributes to a greater understanding of what comics readers, whose perspectives like those of any other reader have been honed by the web environment (in particular the commercial web environment), expect from web resources as well as devices, apps, and social media. Digital comics and webcomics readers bring all of these expectations from this environment and also the unique perspective that has been conditioned by the very nature of comics themselves.

Findings

We had set out in the study to explore, in the broadest sense, the reading experience of digital comics. In this paper, we present the findings that address the readers’ experience: their reading practices in general, including device use, apps, platforms, and specific comics, including webcomics. Our analysis revealed that, despite the age range and disparate occupational backgrounds (data which was volunteered during the sessions), there were shared experiences across the different reading applications, platforms, and devices relating to pace, interaction, anticipation and suspense, as well as the haptics of touch.

How and where they read (devices, apps, platforms)

Immediately before reading your email I was downloading a graphic novel I backed on Kickstarter to the Books app on my iPad via Dropbox … I read comics via Comixology, Kindle and as PDFs on both iPad and iMac (and in hard copy too). (Email from digital comics reader participant DCR4)

DCR4’s description of multiple devices and platforms above reflected the readers’ complex personal digital environment, including apps and platforms, as well as smartphones, laptops, tablets, and PCs or iMacs (sometimes sequentially as demonstrated by DCR4). However, tablets (Kindle, iPad, Kobo) were the preferred device for apps (Marvel Unlimited (Citationn.d.), Comixology (Citationn.d.) (now Amazon), GooglePlay (specifically to read Image Comics (Citationn.d.)), Sequential (Citationn.d.) (now discontinued)), and smartphones were preferred for social media platforms, such as Instagram and Twitter. The smartphone was used by the only reader using the Webtoon (Citationn.d.) app (DCR5), and tablets and laptops were used for PDF versions of comics. One participant, (DCR4), aside from reading through the Comixology app on their tablet, read a lot of comics in PDF form because they had supported a number of comics on Kickstarter (Citationn.d.) where books, mainly graphic novels, are published in PDF format.

Reading via apps predominated among the study participants, whether it be comic books or webcomics. However, one regular reader (DCR3) of Randall Munroe’s (Citationn.d.) webcomic, xkcd, read it sometimes on Instagram using a smartphone but felt the functionality was compromised. They often left their Instagram feed to go to the xkcd account or web page to read it properly. For the most part, they preferred to read it on a laptop via the xkcd website. Although DCR4 read via the Comixology (Citationn.d.) app on an iPad, they would only purchase graphic novels in the form of ebooks via the Comixology (Citationn.d.) website (now Amazon) on the iMac.

Device use was also dictated by where participants were when reading: for example, DCR3 preferred to read on the sofa with the laptop (their partner read from the PC in the upstairs office when working from home), while DCR4 preferred a comfortable chair with the tablet. DCR5 grabbed the phone by the bedside for what they described as “insomnia reading”.

In addition, the choice of the device also had an impact on the physical positioning of the body while reading: DCR5 who read primarily on the smartphone described and physically mimed their position while reading. They would sit all hunched over, clutching the phone either closer or further away from their body:

if it’s not a better one I’ll kind of like be looser [ready to abandon that comic and go on to another]. If it’s like too good it almost needs to be out there too [mimics settling in, with a firm grip].

The observations regarding the choice of devices offer an interesting correlation between container or device and what was being read. This is not necessarily a new approach to reading: consider the different containers for print reading, including books, magazines, newspapers, which also correlate to print comics reading. Instead of being obtrusive, these print containers disappear (physical attributes fall away) when the reader is immersed in the reading experience (see Kashtan's (Citation2018) discussion of the crystal goblet method of typography, p.8). Indeed, in comics “materiality is much harder to ignore” (Kashtan, Citation2018, p. 11), and with the devices required to read digital comics, materiality becomes even more of an issue. In demonstrating the reader’s response to devices, our empirical data illustrates that, while the materiality of devices can be problematic, for example size of screen, it can also enhance the reading experience (see next section).

Regardless of the required investment in a reading device, the print versus digital comic decision was most notably expressed by these participants from an economic perspective. Digital was cheaper, easier and quicker. Print was nice for some but was considered more of an investment.

Reading experience

Pace and interaction

The experience of reading digital comics required a number of conditions in order for it to be a positive one. As mentioned above, where the reader sits and what device is used contribute to a pleasurable experience. The choice of device as noted depended upon the platform. For example, the Comixology (Citationn.d.) and Marvel (Citationn.d.) apps offer a “guided view” of a comic: instead of having multiple comic panels on a single digital page (as with a digitised comic book), each panel is viewed in succession. A few readers referred to this as the “cinematic view”, which was a more pleasurable experience to read on a tablet, such as an iPad, rather than a PC or smartphone.

The touchscreen of a tablet where pages can be “swiped” or “tapped” also contributed to the pace of the reading: DCR4 felt that this interaction with the screen promoted a quicker pace that was conducive to action scenes:

What I did realize as I was switching from hard copy book to digital was that, if anything, I preferred reading digital comics on the iPad because it’s made it more gripping to be engaged actively with moving the story along.

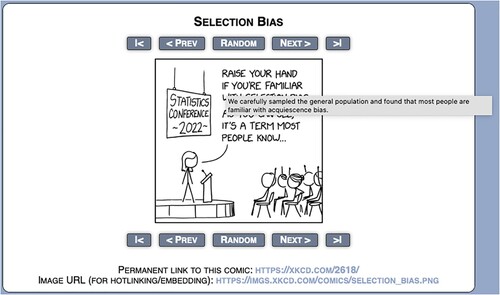

In fact, DCR4 preferred the swiping of a tablet page as opposed to the clicking required on their IMAC: there was something about the swipe-touch that created the same sense of urgency and pace as the action on the screen. The switch to mobile devices did not always enhance the experience of reading a digital comic. The webcomic, xkcd, was originally accessible through a browser on a PC. One of its unique offerings, the “title text” or “mouse hover text” (alt-text) was employed within the image so that additional (but not purely descriptive) bits of information would appear when the mouse pointer hovered over certain parts on a browser version of the webcomic. To achieve this same effect on a social media feed via a smartphone the reader “[clicked] the Alt Text button near the comic title on the mobile site” (see ). This difference in interacting with the comic detracted from the “best bit of fun” for DCR3, a long-term xkcd fan. It was the major reason for not reading it via social media and using their laptop instead. They maintained that the “mouse hover” was the best part of the comic and that the Alt Text option on Instagram is “a blunt instrument”.

Figure 2. Selection Bias, xkcd by Randall Munroe. Retrieved from https://xkcd.com/2618/. In the above web browser version alt -text appears as a mouse hover feature. In DCR3’s reader observation session, they compared this to what alt -text looks like for the same comic on Instagram.

According to Chute (Citation2011), “comics is, above all, a haptic form” (p.112). This study raised a number of points about haptics or understanding through touch (Hague, Citation2014). Of special note is the desirability of different interactions, for example, the hover over a text being more enjoyable, “fun”, creating more anticipation than the simple click. In fact, the click was perceived as a lesser experience by at least two readers (DCR3, DCR4). For DCR4, the swipe touch made for a more enjoyable experience, whereas for DCR3 the hover of a mouse pointer made for a different, better experience than clicking with that same mouse. In both instances, the material interaction contributed to the experience: through the tactile sense, they were able to seek out (through device choice) and create an experience more conducive to their enjoyment.

This connection of pace in the story to the physical action of swiping is also related to the control of the reading experience: in the guided view or “cinematic view”, the reader has less control because they cannot see ahead as they can in a multipaneled page. So, in a sense, they have less control, less preparedness for what will happen, less knowledge of what is around the corner. This can be seen as a positive as DCR4 observed that readers are protected from this additional knowledge, these spoilers. In fact, they thought it a failing of print comics, this struggle to not spoiler content that was so openly presented on a single, multi-panel page or double-page spread. But with the “cinematic view”, they are in control of the pace: how fast they get to the next panel, how slowly if they choose to zoom in/out to consider features in more depth and at their leisure.

Anticipation and suspense

Digital comics are often conflated with animation. In other words, when searching for a definition of digital comics, animation is often included. While we have adopted a broad definition of digital comics that includes the likes of graphic novel ebooks, for instance, it does not include animation where some may consider innovation lies. It has been previously argued that “comics may do things on the screen that cannot be done on paper and vice versa, but […] synchronous animation with sound belongs to a different realm in which comics stop being comics” (Priego, Citation2011, p. 276). That this research has adopted this distinction between comics and animation is an acknowledgement that there are specific functionalities of comics in the digital environment, one of them being movement: not movement powered by animation technology, but inherent in the sequential nature of comics themselves, present in both digital and print versions.

In essence, digital comics embody a sense of movement and time elapsing all their own. The readers in this study confirmed this view. With the more “static” or panel-based digital comic, the reader exerted more control of the experience and was more active, interactive with the panel-by-panel or cinematic view. Animation, however, almost forced a more passive experience and one that was not necessarily a reading experience. As mentioned by DCR3, gaining access to hypertext information through mouse hover made the experience of reading “fun”, conferring an activity that would not necessarily be available in animation.

Other readers, DCR1, DCR4, and DCR5 for example, did observe that the “cinematic view” almost approximated animation, but only in the sense that the quicker they moved from page to page, the more similarity to animation. Again, the reader determined the pace, aided by the creator. Of course, slowing down this movement from page to page also heightens what readers referred to as “the cliffhanger effect”. This effect, as mentioned above, present in both digital comic book and vertical webcomic apps, is a uniquely digital affordance: in fact, DCR4 observed that this difficulty in “burying” or “hiding the big reveal” has been a problem for print comics “for years”.

Vertical comics, essentially the presentation of webcomics on smartphones as exemplified by Webtoon, provide a different kind of tactile interaction with the device and content, one that contributes just as much to the sense of anticipation: scrolling. Instead of clicking or swiping to the next panel, webcomics apps require scrolling, much the same action as reading social media feeds. However, this kind of scrolling is far from what is generally perceived as the negative, non-productive experience of doom-scrolling (generally defined as obsessive scrolling through negative news, it has come to mean just scrolling obsessively). Webcomic scrolling offers a different experience, whereby the more white space between panels, the more scrolling, the more anticipation (Berube, Citation2022; Presser et al., Citation2021).

Indeed, DCR5, the dedicated Webtoon reader, described the experience this way:

… The more dramatic the scene, the more white space will separate it from other scenes. Sometimes it takes quite a bit of scrolling to get to the next panel … the white space does create a lot of anticipation … It really works like that heartbeat sensation, like boom boom that happens in movies … And it had been like a heart stopping moment … gut wrenching, all of this causing anticipation, etc.

Moreover, they found the vertical formatting of comics for the smartphone more accessible, more inclusive than innovative print and digital comics where creators experiment with the placement of panels. For these comics, the progression of panels, which panel to read next, is not so obvious. They referred to the layout of some experimental comics as being “overwhelming”, referring to autism and “sensory overload” because it is not always clear what direction they are to be read in:

there are a lot of rules to how to read a comic, and the rules are dictated by the writer. Because someone wants you to read left to right or right to left … some have random diagonal [layouts]. It’s a lot easier in a Webtoon comic to control that flow.

Enhancing the experience for all readers

In the sessions, readers spoke about how digital comics, including webcomics and comics on apps, can provide an experience that is unique and independent of print. This experience can enhance their reading. For example, the observation of the Webtoon reader regarding the problematic directional placement (often regarded as innovative) of panels in print comics demonstrates that the vertical digital format makes for a more pleasurable reading experience for those who would have difficulty following the sequence of panels on the page. So, the innovation is not just the technical application as it addresses the formatting for smartphone reading, but the accessibility and reading experience of the digital comic.

The study demonstrates that the device in combination with the platform needs to work to enhance the reading experience and that the combinations and experiences may be different for each reader. There is the problem, for example, of what happens to hypertext information, such as Alt Text, readable in a browser on a laptop or PC by hovering over images, but not as interactive when it is offered as clickable Alt Text in a social media feed on a phone. In addition, some comics, converted from print to digital browser reading and then fitted into a social media feed, just do not work: DCR1 discussed this experience with the comic strip Calvin and Hobbes which they accessed primarily through Instagram. The entire comic had to be read on a browser website, the Instagram feed only offered a few panels. DCR3 noticed during the observation session that they had to go from the vertical reading in an Instagram feed to the horizontal reading in a browser in order to read the complete comic, one that had begun life digitally on a website. DCR2 maintained that they wanted digital comics “to function like books”, and so set about using the functionality on devices and apps to make what they are reading look as much like a book as possible. These manoeuvres between platforms, browsers, devices, apps to get the reading experience to adhere to their preferences indicate that readers approach the digital environment with “cognitive maps”, that is preconceived mental models for what that experience should be (Bjornson, Citation1981; Thayer et al., Citation2011; Zifu et al., Citation2020).

They also indicate that design for immersive reading should reflect the multiple reader experiences even when this means facilitating the closing off of hypermedia as a distraction from a more immersive experience. Although some participants mentioned enjoying other media, such as audio and interactive accompaniments, they wanted agency over what they wanted and at what juncture in the narrative. Some scholars maintain that hypertext can only be considered as a positive augmentation of the text “if the reader feels able to trust that the psychological conditions provided by the text justify this involvement” (Mangen and van de Weel, Citation2016, p.171). Indeed, DCR5 emphasised trust as one of the important reasons why they read comics on Webtoon: after seeing various new comics promoted on the web, their reaction was “that comic looks awful. Why do that? And they all seemed like really scary things. And then I found Webtoon”. For them, there was less likelihood of feeling offended over the representation of different ethnicities, for example. This environment of trust made them more open to music or animation or following hypertext links, even if it did require audio adjustment or interrupted reading the webcomic in sync with their partner (they shared the reading experience of webcomics by reading them at the same time, sat side by side).

Conclusion and recommendations

This empirical and exploratory study has not only achieved the original research aim of understanding how readers read and respond to digital comics and the devices used to access them but also how HCI methods can elicit rich data that more deeply reflects and illustrates that multi-faceted response. It addresses a research gap where readers have been under-researched and overtheorised. We did not direct readers to consider the materiality of digital comics: our questions broadly addressed the “what”, “where”, “when” and “how” of their experiences. That they came back in the observation sessions with strong reactions and opinions about their physical interaction, especially from a tactile perspective, indicates that the reading of digital comics can be and is a compelling, multi-layered, multi-sensory experience, and not just an electronic version of print books on the one hand and a static version of animation on the other (Côme, Citation2017). In this study, researchers and readers read together in real-time so that the responses were not just described, but “embodied”: “cognition is embodied and concrete rather than disembodied and abstract” (Sadoski, Citation2018, p. 333). The defined boundaries of human cognition have expanded; cognition is now regarded by many to “spill over” from the mind into the environment (with the notion of “embodied cognition”), including onto the devices people use. These findings highlight the embodied nature of cognition in digital comics reading, where the experience is highly material, immersive, and enjoyable. The result was a richer dataset where description and experience combined to illustrate a complex reading experience combining imagination and senses.

According to comics scholar Scott McCloud (Citation1994), readers are “equal partners” in the creation of comics. However, 20 years on, Hatfield (Citation2022) still questions whether or not readers are truly active or passive participants. These empirical findings demonstrate that the reading of digital comics cannot be so easily categorised: DCR3, for example, illustrated in their ITA active involvement through pace and anticipation expressed through the device. Not only do their imaginings expand on what the comics creator has set before them, but the use of the device, how quickly they move from panel to panel, for instance, demonstrates an input into how the comic is experienced. However, they also demonstrated the passivity of the reader in that same session, waiting for both a screen and a cliffhanger to resolve. This duality would be difficult to capture with just a survey or interview both of which tends to remove the reader from the reading experience. The small reader sample served to highlight the complexity of the reader experience through immediate context and diverse avenues for feedback. Future empirical research with larger samples should combine qualitative methods such as survey and interview with contextual observation in order to build upon the work of this study. The combination of the theoretical tested and realised through the empirical will provide a framework by which to understand how readers make their way through digital comics and indeed other electronic fiction, not just in a cognitive way, but in an immersive and embodied one.

Moving with the Story_New Review_Margins_Bios.docx

Download MS Word (33.7 KB)Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Additional Student Development Fund and conducted in conjunction with Linda Berube’s AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Partnership PhD research supported by the Centre for Human–Computer Interaction Design, City, University of London and the British Library.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Antonini, A., Brooker, S., & Benatti, F. (2020). Circuits, cycles, configurations: An interaction model of web comics. In A. G. Bosser, D. E. Millard, & C. Hargood (Eds.), Interactive storytelling. ICIDS 2020 (pp. 287–299). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62516-0_26

- Arai, K., & Mardiyanto, R. (2011). Eye-based human computer interaction allowing phoning, Reading e-book/e-comic/e-learning, internet browsing, and tv information extraction. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 2(12), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2011.021204

- Benatti, F., Berube, L., & Priego, E. (2023, November 3–6). Web/comics 2023: Webcomics and/as hypertext. HT ‘23: Proceedings of the 34th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media. Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3603163.3610574

- Berube, L. (2022). UK digital comics: More of the same but different? British Library Digital Scholarship Blog, (18 July). Retrieved December 04, 2023, from https://blogs.bl.uk/digital-scholarship/2022/07/uk-digital-comics-more-of-the-same-but-different.html

- Berube, L., Makri, S., Cooke, I., Priego, E., & Wisdom, S. (2023, March 19–23). “Webcomics archive? Now I'm interested”: Comics readers seeking information in web archives. Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Human Information Interaction and Retrieval. (pp. 412–416). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3576840.3578325

- Bjornson, R. (1981). Cognitive mapping and the understanding of literature. SubStance, 10(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/3684397

- Brown, J. A. (1997). New heroes: Gender, race, fans and comic book superheroes. University of Toronto.

- Brown, J. A. (2009). Black superheroes, milestone comics, and their fans. University Press of Mississippi.

- Brown, K. (2018). Comics, materiality, and the limits of media combinations. Image Text Journal, 9(3), Retrieved December 04, 2023, from https://imagetextjournal.com/comics-materiality-and-the-limits-of-media-combinations/

- Butler, B. (2021). British Library Reader and Non-User Research Report. (unpublished report).

- Chute, H. (2008). Comics as literature? Reading graphic narrative. PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America, 123(2), 452–465. https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2008.123.2.452

- Chute, H. (2011). Comics form and narrating lives. Profession, 2011(1), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1632/prof.2011.2011.1.107

- Cohn, N. (2013). Navigating comics: An empirical and theoretical approach to strategies of reading comic page layouts. Frontiers in Psychology, 4(186), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00186

- Cohn, N., & Maher, S. (2015). The Notion of the motion: The Neurocognition of motion lines in visual narratives. Brain Research, 1601(15 March), 73–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2015.01.018

- Côme, M. (2017). With, against or beyond print? Digital comics in search of a specific status. The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship, 7(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.16995/cg.106

- Comixology. (n.d.). Retrieved December 04, 2023, from https://www.amazon.co.uk/kindle-dbs/comics-store/home

- Dittmar, J. (2012). Digital comics. SJoCA Scandinavian Journal of Comic Art, 1(2), 82–91.

- Goodbrey, D. M. (2013). Digital comics–new tools and tropes. Studies in Comics, 4(1), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1386/stic.4.1.185_1

- Groensteen, T. (2007). The system of comics. University Press of Mississippi.

- Ha, J., & Kim, S. (2016). Mobile Web-toon application service usability study: Focus on Naver Web-toon and Lezin Comics. Journal of Digital Convergence, 14(9), 431–436. https://doi.org/10.14400/JDC.2016.14.9.431

- Hague, I. (2014). Comics and the senses: A multisensory approach to comics and graphic novels. Routledge research in cultural and media studies. Routledge.

- Hatfield, C. (2022). The empowered and disempowered reader: Understanding comics against itself. Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society, 6(3), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1353/ink.2022.0024

- Hillesund, T., Schilhab, T., & Mangen, A. (2022). Text materialities, affordances, and the embodied turn in the study of Reading. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 827058. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.827058

- Hussie, A. (n.d.). Homestuck. Retrieved om December 04, 2023, from https://www.homestuck.com/

- Image Comics. (n.d.). Retrieved December 04, 2023, from https://play.google.com/store/books/theme/promotion_1000a03_image_comics

- Kashtan, A. (2018). Between Pen and pixel: Comics, materiality, and the book of the future. Ohio State University Press.

- Kickstarter. (n.d.). Retrieved December 04, 2023, from https://www.kickstarter.com/

- Kleefeld, S. (2020). Webcomics. Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350028210

- Lamerichs, N. (2020). Scrolling, swiping, selling: Understanding webtoons and the data-driven participatory culture around comics. Participations: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies, 17(2), 211–229. Retrieved December 04, 2023, from https://www.participations.org/17-02-10-lamerichs.pdf

- Larradet, F., Niewiadomski, R., Barresi, G., Caldwell, D. G., & Mattos, L. S. (2020). Toward emotion recognition from physiological signals in the wild: Approaching the methodological issues in real-life data collection. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1111. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01111

- Lieske, D. (n.d.). The Wormworld saga. Retrieved on December 04, 2024, from https://wormworldsaga.com/

- Makri, S., Chen, Y., McKay, D., Buchanan, G., Ocepek, M. (2019). Discovering the unfindable: The tension between findability and discoverability in a bookshop designed for serendipity. In D. Lamas (Ed.), Human-Computer interaction – INTERACT 2019 (IFIP conference on human-computer interaction), Lecture notes in computer science, 11747 (pp. 3–23). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29384-0_1 or Retrieved December 04, 2023, from https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/22383/

- Mangen, A. (2008). Hypertext fiction Reading: Haptics and immersion. Journal of Research in Reading, 31(4), 404–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2008.00380.x

- Mangen, A., & van der Weel, A. (2016). The evolution of reading in the age of digitisation: An integrative framework for reading research. Literacy, 50(3), 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12086

- Marvel Unlimited. (n.d.). Retrieved 04 December 2023 from https://www.marvel.com/unlimited

- McCloud, S. (1994). Understanding comics: The invisible art. HarperPerennial.

- Moura, P. (2014). Interview with Ian Hague. Studies in Comics, 5(2), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1386/stic.5.2.259_7

- Munroe, R. (n.d.). xkcd, a webcomic of romance, sarcasm, math, and language. Retrieved December 04, 2023, from https://xkcd.com/

- Murray, P. R. (2012). Scott pilgrim vs the future of comics publishing. Studies in Comics, 3(1), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1386/stic.3.1.129_1

- O’Brien, L., & Wilson, S. (2023). Talking about thinking aloud: Perspectives from interactive think-aloud practitioners. Journal of User Experience, 18(3 May), 113–132.

- Presser, A., Braviano, G., & Corte-Real, E. (2021). Webtoons. A parameter guide for developing webcomics focused on small screen Reading. Convergências - Revista de Investigação e Ensino das Artes, 14(28), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.53681/c1514225187514391s.28.28

- Priego, E. (2010). The Digital Scriptoria: Textuality and materiality. In Cultural Materialism, Comics and Digital Media. Opticon1826 9. Retrieved 04 December 2023 from https://student journals.ucl.ac.uk/opticon/article/id/942/

- Priego, E. (2011). The comic book in the Age of digital reproduction [PhD dissertation]. University College London. Retrieved December 04, 2023, from https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.754575.v4

- Priego, E. (2012). Beyond [Adobe] Flash™: Flash: Hans Bordahl’s and David Farley’s online comics as short digital narratives. Dandelion, 3(1), 1–5.

- Priego, E., & Farthing, A. (2020). Barriers remain: Perceptions and uses of comics by mental health and social care library users. Open Library of Humanities, 6(2), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.98

- Rosenblatt, L. (1982). The literary transaction: Evocation and response. Theory Into Practice, 21(4), 268–277.

- Royer, G., Nettels, B., & Aspray, W. (2011). Active readership: The case of the American comics reader. In W. Aspray & B. M. Hayes (Eds.), Everyday information: The evolution of information seeking in America (pp. 277–304). MIT Press.

- Sadoski, M. (2018). Reading comprehension is embodied: Theoretical and practical considerations. Educational Psychology Review, 30(2), 331–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-017-9412-8

- Sequential. (n.d.). (formerly an app available through Apple, by publisher Panel Nine). Retrieved December 04, 2023, from http://www.paulgravett.com/articles/article/sequential

- Serantes, L. C. (2014). Young adults reflect on the experience of reading comics in contemporary society: Overcoming the commonplace and recognizing complexity [Doctoral dissertation]. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2075. The University of Western Ontario (Canada).

- Serantes, L. C. (2019). Young people, comics and Reading: Exploring a complex Reading experience. Elements in publishing and book culture series. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781109568845.

- Thayer, A., Lee, C. P., Hwang, L. H., Sales, H., Sen, P., & Dalal, N. (2011, May 7–12). The imposition and superimposition of digital Reading technology: The academic potential of e-readers. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ‘11) (pp. 2917–2926). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979375

- Thon, J. N., & Wilde, L. (2016). Mediality and materiality of contemporary comics. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 7(3), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2016.1199468

- van der Bom, I., Skains, R. L., Bell, A., Ensslin, A., (2021). Reading hyperlinks in hypertext fiction: An empirical approach. In A. Bell (Ed.), Style and reader response: Minds, media, method (pp. 123–142). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Voit, A., Mayer, S., Schwind, V., & Henze, N. (2019, May 4–9). Online, VR, AR, Lab, and In-situ: Comparison of research methods to evaluate smart artifacts. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ‘19) Paper 507 (1–12). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300737

- Webtoon. (n.d.). Retrieved December 04, 2023, from https://www.webtoons.com/

- Wilde, L. (2015). Distinguishing mediality: The problem of identifying forms and features of digital comics. Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, 8(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.31165/nk.2015.84.386

- Woo, B. (2012). Understanding understandings of comics: Reading and collecting as media-oriented practices. Participations: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies, 9(2), 180–199. Retrieved December 04, 2023, from https://www.participations.org/09-02-13-woo.pdf

- Woo, B. (2020). Readers, audiences, and fans. In C. Hatfield & B. Beaty (Eds.), Comics studies: A guidebook (pp. 113–125). Rutgers University Press.

- Zhao, F., & Mahrt, N. (2018). Influences of comics expertise and comics types in comics Reading. International Journal of Innovation and Research in Educational Sciences, 5(2), 218–224. Retrieved December 04, 2023, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330753904_Influences_of_Comics_Expertise_and_Comics_Types_in_Comics_Reading

- Zifu, S., Ting, T., & Lin, Y. (2020). Construction of cognitive maps to improve Reading performance by text signaling: Reading text on paper compared to on screen. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(57), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.57195