ABSTRACT

Numerous scholars have emphasised that interfaith initiatives can contribute to personal transformation and enhance social cohesion, but it is often unclear if and how these initiatives effectively bring about the intended changes. This article argues that setting up a shared framework of interfaith learning objectives is a necessary first step towards organising and evaluating interfaith initiatives. After conducting a systematic scoping review, we categorised and summarised the learning objectives of 93 interfaith initiatives. These learning objectives are presented in a matrix of twelve categories, reflecting the learning objectives set by the organisers of the 93 initiatives. This article is intended as a first step towards building a shared scholarly framework that can then be used to guide the organisation and evaluation of interfaith initiatives. The matrix can encourage organisers of interfaith initiatives to clarify their learning objectives and, consequently, develop more coherent and evaluable initiatives.

Introduction

Since 9/11, the number of interfaith initiatives has proliferated rapidly at local, national, and international levels. These initiatives have also received increasing scholarly attention worldwide (Griera and Nagel Citation2018; Cheetham, Pratt, and Thomas Citation2013). Interfaith initiatives can be defined in their broadest sense as organised activities that intentionally involve people who orient around religion differently (Pedersen Citation2004, 79). These activities are organised by various stakeholders: from religious institutions to academic organisations (McCarthy Citation2007a, 18,9). A plethora of academic research has emphasised that interfaith initiatives can contribute to personal transformation and enhance social cohesion (Halafoff Citation2013). Scholars increasingly recognise ‘the opportunity and responsibility of the educative process to create a bridge to understanding difference’ (Byrne Citation2011). While the interfaith movement is proliferating, the current approach towards organising interfaith initiatives can best be described as a process of ‘moving experimentally into an unknown future’ (Berling Citation2020, 9), since the organisers are as yet unable to provide a clear answer as to whether and how their pedagogy and didactics are effective in bringing about the intended transformations (Garfinkel Citation2004). Several scholars have ascertained that few interfaith initiatives provide ‘well-defined evaluation criteria’ for reflecting on their impact (Vader Citation2015, 38; cf. McCallum Citation2018; Seyle et al. Citation2021). However, the challenge we observe is even more profound: there is no shared framework to analyse and formulate the learning objectives of interfaith initiatives. We perceive both theoretical and empirical lacunae regarding this challenge (cf. Abu-Nimer Citation2021). First, scholars use disparate concepts and terms to describe the objectives of interfaith learning, and this conceptual vagueness prevents the establishment of clear and practical evaluations. The conceptual ambiguity also hinders the advancement of the scholarly field of interfaith learning: when scholars use various terms and concepts, they run the risk of being at cross purposes with each other or misunderstanding and misinterpreting the work of other scholars. Second, the missing consensus precludes organisers of interfaith initiatives from formulating well-defined and explicit learning objectives and, consequently, determining which activities and evaluations best suit their purposes (cf. Biggs Citation1996, Citation2003). By conducting the first systematic scoping review in the field of interfaith learning, the current article aims to achieve more clarity and presents a matrix of interfaith learning objectives and provide direction for scholars, organisers, and teachers worldwide, as this article reviews a breadth of international literature and a variety of initiatives and their learning objectives. The main question that guides this article is: What are the learning objectives of the interfaith initiatives included in our scoping review, and how can we summarise and categorise these learning objectives in a matrix?

Methods

In this literature review, we followed the method of a scoping review, which begins with developing a protocol, followed by an extensive search of the international literature, with the aim of mapping literature to address a broader research question (Peters et al. Citation2015, 142). We followed the five stages of a scoping review by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005), 1) identifying the research question, 2) identifying relevant studies, 3) study selection, 4) charting the data, and 5) collating, summarising and reporting the results.

Search strategy

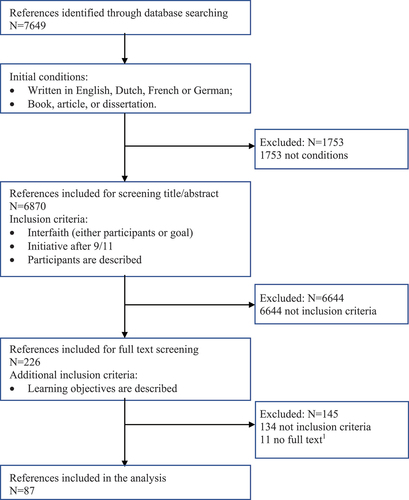

We performed a search in the bibliographic databases ATLA Religion Database, PsycINFO, Eric, Scopus and Philosopher’s Index. We searched using the terms ‘interfaith’ (and neighbouring terms such as interreligious, religiously diverse, Muslim-Jewish, Christian-Hindu, and so on) and ‘competence’ (and closely related terms such as ‘skills’, ‘capabilities’, ‘quality’, ‘development’, et cetera).Footnote1 While we were aware of the different connotations, meanings, and emphases of these terms and their synonyms, we aimed for a search strategy that includes as many relevant initiatives as possible.Footnote2 A total of 7649 references were identified through database searching. Two reviewers screened these references independently in the review programme Rayyan QCRI and then compared and discussed their findings (HJV and AIL). We included a reference wherever it involved a description of one or more interfaith initiatives and described the learning objectives set for participants. Interfaith initiatives were defined as organised activities that intentionally include people from more than one faith or non-faith tradition (Pedersen Citation2004, 79). The reference was included if it was written in English, Dutch, French or GermanFootnote3 and published as a book, article or dissertation. Furthermore, since ‘the tragedy of September 11 (…) served as a stimulus for multifaith engagement at local, national and global levels’ and altered the numbers and types of initiatives (Halafoff Citation2013, 164), we only included references to initiatives that took place after 9/11. For the flow diagram, see .

Data analysis

Once we had identified the relevant references, we listed the learning objectives of the described initiatives. Three reviewers (HJV, AIL and MM) worked together to design a matrix that included all objectives in diverse rounds. After each round, the first author (HJV) recoded the objectives using this matrix to assess whether it covered all the objectives. Using this inductive approach with several rounds of coding, recoding, and adjusting the matrix, we designed a matrix with two axes that best suited the learning objectives we included according to our academic and pedagogic appraisal. The first axis refers to ‘the self’, ‘the other’ and ‘interaction’ on a personal or societal level. While we developed this axis inductively, based on the learning objectives, we can observe a parallel between this axis and the description of learning ‘about’, ‘from’, and ‘in’ religion (Halsall and Roebben Citation2006, 448; Grimmitt Citation1987, Citation1994). We also see parallels between this axis and the hermeneutic approach, which entails a ‘movement from the outside to the inside’ and a back-and-forth between self and other (Pollefeyt Citation2020).

Similarly, the second axis consists of knowledge, skills and attitudes (KSA), which parallels Bloom’s (Citation1956) three models of educational learning objectives. In the context of interfaith learning, we were inspired by the interfaith triangle, which consists of knowledge, attitudes and relationships.Footnote4 We follow Schwandt (Citation1999, 452) in that knowledge can refer to both ‘a cognitive and intellectual achievement’ and the ability for participants ‘to grasp, to hear, get, catch, or comprehend the meaning of something,’ which is typically described as understanding. Skills can be defined as ‘the ability to perform a certain physical or mental task’ (Spencer and Spencer Citation1993, 11). Lastly, in line with Albarracín et al. (Citation2005, 5), we describe attitudes as ‘evaluative tendencies, which can both be inferred from and have an influence on beliefs, affect, and overt behaviour’, and which include, for instance, self-concept and values as well (Spencer and Spencer Citation1993, 11). Similar to the interfaith triangle, we assume that each category influences and is interrelated with the other two.4

In conclusion, while we developed the matrix inductively, it is grounded in previous academic work in interfaith studies and education. The matrix suggested in this article should be seen as a first step that can engender further scholarly debate on interfaith learning objectives. In the conclusion of this article, we reflect on the possibilities and challenges relating to this matrix.

Results

Characteristics of the references included

In this scoping review, 87 references are included, of which 28 are theoretical and 59 empirical. These references also vary regarding their discipline (psychology, pedagogy, theology) and their purposes.Footnote5 Some authors describe an initiative they developed and facilitated themselves, while others describe an initiative from an outsider’s position. Together, these references portray 93 initiatives with an average of two to three learning objectives per initiative. The initiatives were located in 22 countries, and seven initiatives were situated in multiple countries. The majority of the initiatives (59) took place in North America, 56 of which were in the USA; 22 were located in Europe; seven in Asia; six in Africa; three in the Middle East; three in Australia; and one globally. Latin American initiatives were not represented in the references that we have included. In addition, the majority of initiatives (69) took place in colleges or primary and secondary schools, while the other initiatives were organised in a variety of other settings, such as women’s book clubs, environmentalist activities, or conferences.Footnote6

Matrix of interfaith learning objectives

We identified 12 main learning objectives and organised them into a matrix with two axes. We observed a distinction in these objectives between the self (one’s own position), the other (another person or worldview), and the interaction (the encounter between two or more parties). The interaction objectives are twofold: interactions on a personal level and on a societal level. Additionally, we distinguished objectives that focus on knowledge, skills, and attitudes. The matrix also indicates the number of times we found each of the learning objectives in the literature (see ).

Table 1. Matrix of interfaith learning objectives.

In what follows, we summarise each learning objective and identify the different aspects and tendencies within each of them. We also highlight the approaches to this learning objective that typify the descriptions in the references we included. Since these results are based on the references we found, including their descriptions of the learning objectives, existing ambivalences regarding terminologies also persist in describing each learning objective. In the conclusion, we will reflect on the ambiguities of the results and the challenges they pose.

Knowledge

(1) Knowledge, Self: Knowledge About One’s Own Worldview

This first learning objective entails an understanding of one’s own worldview. It is identified as a learning objective by only a very few initiatives. One of these is the initiative that Callahan and Benner (Citation2018) describe in their article. Their initiative aims to develop spiritual competences and sensitivity, which, according to the authors, can be found in knowledge about ‘one’s own beliefs about the world’ (Callahan and Benner Citation2018, 183). Such knowledge is needed to ensure that one understands ‘the limitations and biases associated with one’s worldview’ (Hodge Citation2018, 126, referred to in Callahan and Benner Citation2018). Overall, this learning objective implies an understanding of the different aspects, the history, the blind spots and the internal diversity of one’s own worldview.

(2) Knowledge, Other: Knowledge About Other Worldviews

In general, the initiatives whereby the aim is that participants gain knowledge about other worldviews focus on lived religion.Footnote7 While some initiatives describe acquiring general knowledge about world religions (e.g. Herzog et al. Citation2016), most initiatives concentrate on different types of knowledge. For example, students should learn as ‘embodied beings who inhabit a space, engage in physical activities, and undergo various sensory experiences’ (Long Citation2018, 79), and learn from lived experiences and exchange, with consideration of intra-worldview diversity (Allen Citation2016; Green et al. Citation2018; Locklin, Tiemeier, and Vento Citation2012; Hayik Citation2015; McCowan Citation2017). The initiatives tend to centralise the lived and experiential aspects of different worldviews because they want their participants to recognise the internal diversity within different worldviews (Green et al. Citation2018; Long Citation2018; Yuskaev Citation2013; Daddow et al. Citation2019; Mardell and Abo-Zena Citation2010).

(3) Knowledge, Interaction Personal: Knowledge About Each Other’s Perspective

The objective of gaining knowledge about each other’s perspectives relates closely to the two learning objectives described above. While these objectives focus either on the self or the other, this learning objective refers to knowledge about oneself and others through interaction. Even though the descriptions of this learning objective are not elaborate, the initiatives suggest an open and dialogical exchange in which participants interact with and learn about the experiential dimensions of their own and the other’s worldview. Various references make notice of interfaith, dialogic and participative knowledge as one of the initiative’s learning objectives (Acar Citation2013; Allen Citation2016; Gramstrup Citation2017, Citation2018; Lin, Edwards, and Khami Citation2016; Mason Citation2016; Mayer et al. Citation2016a, Citation2016b; McCowan Citation2017; Knysh et al. Citation2019). All of the initiatives that indicate this learning objective recognise the potential of learning in interaction.

(4) Knowledge, Interaction Societal: Knowledge About Context

Although never described in great detail, several initiatives accentuate the importance of learning about the context in which one works, lives or studies (Pallavicini Citation2016; Lyndes, Cadge, and Fitchett Citation2018; Epstein Citation2018). They tend to emphasise the importance of paying attention to injustices and conflicts and of understanding hidden positionalities and power relations; they also focus on knowledge about the sociopolitical structures of privilege and oppression in society (Hayik Citation2015, 94; Miller et al. Citation2012; Lin, Edwards, and Khami Citation2016). Furthermore, this learning objective addresses historical and psychological challenges and the deep, historical roots of many faith and non-faith perspectives (Allen Citation2016, 5). Participants learn to understand possible systematic challenges they may face as interfaith actors within their own contexts.

Skills

(5) Skills, Self: Self-Reflection and Explication

This learning objective consists of two central dimensions, often, but not always, described simultaneously: self-reflection and self-explication. These two dimensions complement each other, as is stressed by several references: in order to voice one’s opinions, explain one’s own behaviour and articulate one’s personal values, one needs first to reflect on them (Herzog, Harris, and Peifer Citation2018; Moyaert Citation2017; Bouchard Citation2009). However, some authors describe only one of the two dimensions. First, self-reflection skills are identified as the ability to reflect on one’s own values, opinions, prejudices, privileges and attitudes (Francis, Astley, and Parker Citation2016; Francis, Village, and Parker Citation2017; McCarthy Citation2007b; Sloan-Power Citation2013; Edwards Citation2017). On the other hand, self-explication skills are described as the ability to articulate and voice one’s beliefs, opinions, behaviour, and values (Luby Citation2014, Citation2020; Patel and Meyer Citation2012). Thus, this learning objective consists of reflecting on and articulating one’s beliefs and considering and explaining one’s behaviour. This reflection and explication can help participants understand how their own and others’ perspectives are influenced by their beliefs, values, privileges, and experiences to establish positive relations with others (Patel and Meyer Citation2012; Sorensen et al. Citation2009; referred to in Edwards Citation2017).

(6) Skills, Other: (Re)Presenting Other Worldviews

A small number of initiatives aim to develop the ability to compare and represent various worldviews, including their internal diversity. The descriptions of this learning objective within the literature we analysed were equivocal. However, we would illustrate this learning objective by giving an example: being aware of the various traditions’ days of rest and food preferences and arranging the event accordingly when organising an interfaith event. In other words, this learning objective is about one’s ability to compare different worldviews and to apply knowledge about them in one’s interfaith action (Stoltzfus and Raffel Citation2009; Zain et al. Citation2018; Bhatia and Pathak-Shelat Citation2019).

(7) Skills, Interaction Personal: Communication Skills

Numerous initiatives set communication skills as one of their central learning objectives, although they do not refer to a common theoretical framework in their descriptions. This lack of consensus is seen in the variety of communication skills identified: to listen attentively and appreciatively, to search for meaning and values together, to engage with difference and conflict in interactions, to ask questions, to share personal experiences, and to communicate one’s worldview in a ‘language’ that others can understand (Bouchard Citation2009; Brockman Citation2016; Duckworth et al. Citation2019; Hicks and Tran‐Parsons Citation2013; Curpanen Citation2013; Moyaert Citation2017; O’Keefe Citation2009). In some of the references, a specific professional context is described, such as the professional communication skills of counsellors and health care providers (Pearce et al. Citation2020; Shadbolt Citation2017) and the skills teachers need to interact with their students (Abu-Nimer, Nasser, and Ouboulahcen Citation2016; Ambroson Citation2013; Bender-Szymanski Citation2013; Mambu Citation2016; Mohamed Citation2019; Ramarajan and Runell Citation2007; Helskog Citation2015). Most of these initiatives have in common that they aim to get their participants to learn to listen, ask questions, and search for shared values.

(8) Skills, Interaction Societal: Leadership Skills

As with communication skills, leadership skills are commonly identified as a learning objective. Leadership skills can be described as the skills participants need to impact broader communities and address global challenges. This learning objective is about moving from dialogue to societal action and striving for social cohesion. In the descriptions of this objective, we encountered a mix of societal challenges for which leadership is required, such as protecting nature and fighting for climate change (Bjork Citation2019; Del Vecchio Citation2018; McCarthy Citation2007c; Tyler, Valek, and Rowland Citation2005; Warner, Brook, and Shaw Citation2012), against injustice or oppression (Bhadra Citation2018; Diaz-Edelman Citation2014; Edwards Citation2017; Gardner Citation2019; Lin, Edwards, and Khami Citation2016; Lindsay Citation2018; Miles and Mallinckrodt Citation2017; Pallavicini Citation2016; Weller Citation2017; Lewis Citation2012), or even combatting the abuse of the elderly (Proehl Citation2012). Many initiatives that centred on leadership were organised by the Interfaith Youth Core (IFYC). They describe several leadership skills: the ability to narrate a vision of interfaith cooperation, to bring people together, and to build social capital (Basham and Hughes Citation2012; Campbell and Lane Citation2014; Hicks and Tran‐Parsons Citation2013; Jendzejec Citation2018; Krebs Citation2015; Patel and Meyer Citation2011). In conclusion, this learning objective is about acting on behalf of social cohesion and societal challenges and inspiring others to do so.

Attitude

(9) Attitude, Self: (Religious) Self-Awareness

According to some of the references included, ‘most of us are unaware of the entirety of our unconscious biases, behaviours, and projections, as they have become so ingrained through experiences and social, cultural and religious means’ (Mohammed-Ashrif Citation2018, 362). Hence, this learning objective is about becoming aware of one’s own beliefs, purposes, prejudices and privileges and learning how they influence one’s perceptions and interactions. It has a close overlap with the skill of self-reflection/explication, but several authors also explicitly choose to use the term ‘awareness’ (Akdag et al. Citation2019; Ferreira and Schulze Citation2016; McMinn et al. Citation2014; Miller et al. Citation2012; Pearce et al. Citation2020) even though the precise distinction remains questionable. Rather than actively reflecting on and voicing one’s identity, this learning objective is about one’s self-concept and an awareness of one’s values. Besides awareness of participants’ own beliefs and stereotypes, participants may also need to develop an awareness of systematic stereotyping and perceptions of their identities among society at large (Ezzani and Brooks Citation2019, 790; Mason Citation2016; Wilson, Abram, and Anderson Citation2010). In other words: not only should participants learn to be aware of their own worldviews, purposes, prejudices and privileges, they should also become aware of the societal perceptions of their identity.

(10) Attitude, Other: Appreciative Attitude Towards Other Worldviews

A variety of different terms are used within this learning objective, and the interpretation is often unclear.Footnote8 Some authors describe this objective as an attitude of respect and civility towards the other (Beauchamp Citation2012; Haynes Citation2011; Hussien, Hashim, and Mokhtar Citation2017; Kilman Citation2007; Hayden Citation2010; Larson and Shady Citation2013). Other authors use ‘tolerance’ (Bhadra Citation2018; Holden Citation2013) or ‘openness’(Buser and Buser Citation2014) towards different worldviews and diversity. Furthermore, several initiatives aim at a general attitude of appreciation, either as an attitude in itself (Fink et al. Citation2014; Holland and Walker Citation2018; McMinn et al. Citation2014; Pearce et al. Citation2020; Stoltzfus and Raffel Citation2009), or in the context of ‘appreciative knowledge’ vis-à-vis other worldviews (Naumenko and Naumenko Citation2016; Patel and Meyer Citation2012; Poppinga, Larson, and Shady Citation2019). While the terms encompass slightly different characteristics, all of them appear to centralise the development of a positive attitude towards the religious other or towards religious diversity in general; they refer to an inclination to see religious differences not as a threat but as a source of inspiration (Eck Citation2003; referred to in Stoltzfus and Raffel Citation2009).

(11) Attitude, Interaction Personal: Empathy

Although this learning objective is not described in detail by the authors or initiatives included, it appears to consists of both affective and cognitive aspects: the ability to take in another’s viewpoint on the one hand, and the ability to experience the feelings of another on the other hand (Chlopan et al. Citation1985; Mayer and Salovey Citation1993; referred to in Bhadra Citation2018; Davis Citation1996; referred to in Miller et al. Citation2012). Several initiatives aim at this empathetic attitude (Bhadra Citation2018; Callahan and Benner Citation2018; Miles and Mallinckrodt Citation2017; Pearce et al. Citation2020; Miller et al. Citation2012). We can grasp that this learning objective is about viewing oneself and the other through the eyes of that religious other.Footnote9

(12) Attitude, Interaction Societal: Awareness of Injustice

This final learning objective is about developing awareness and motivation concerning societal issues, engaging with broader societal challenges, and finding a sense of urgency to act for improvement (Hoover and Douglas Citation2018; Bhatia and Pathak-Shelat Citation2019). Although a few initiatives only identify this objective, several of them describe critical awareness as an essential aspect of interfaith learning, which requires the ability to identify sources of oppression and power dynamics and to understand the way these dynamics are imported into the interfaith environment (Edwards Citation2017; Ezzani and Brooks Citation2019): ‘injustice and inequity are central drivers of conflict, preventing a culture of peace. Central themes are identifying sources of oppression and considering the power dynamics influencing the students’ environment’ (Duckworth et al. Citation2019, 238). Thus, this learning objective is about the participants’ awareness of society as a place where (religious) privilege and power are ever present and about developing the values to being committed to bringing about a more just society.

Conclusion and discussion

In this article, our purpose was to identify the learning objectives of interfaith initiatives in the scholarly literature and to summarise and categorise these objectives in a matrix. In order to do so, we systematically collected and analysed references in which interfaith initiatives were described, resulting in the analysis of 87 references that together portrayed 93 interfaith initiatives. We identified the learning objectives of these initiatives and, using an iterative inductive approach, categorised them in a matrix of interfaith learning objectives. The matrix comprises the self, the other, and interaction on a personal and societal level along one axis, and knowledge, skills, and attitude along the other, making a total of twelve learning objectives.

Up to now, the literature has offered no shared framework with which to analyse and formulate the learning objectives of interfaith initiatives. This inconsistency was visible at two levels. First, interfaith scholars used contrasting terms when discussing interfaith learning objectives, which hindered the advancement of the scholarly field of interfaith studies. Second, organisers of interfaith initiatives were facing challenges in clearly formulating their learning objectives and organising their programme and evaluation according to those learning objectives. The purpose of this scoping review was to achieve more clarity by summarising and categorising the learning objectives of existing interfaith initiatives in a matrix.

This scoping review has taken a first step towards achieving more clarity about interfaith learning objectives. Although the matrix we have suggested can and should be subject to more scholarly debate, it can nevertheless stimulate organisers of interfaith initiatives to consider and explicate their learning objectives. Clarifying their learning objectives will also facilitate evaluating their initiatives since comparing objectives and outcomes can illuminate whether the learning objectives were met. Furthermore, the matrix can contribute to a shared scholarly language regarding participants’ development in interfaith initiatives, as it is based on the empirical reality of interfaith initiatives and their learning objectives.

Nevertheless, as the matrix is based on the descriptions of existing interfaith initiatives, the ambiguity within the field was inevitably imported into the matrix, which became visible in several ways. First, a myriad of synonyms was used for the key terms ‘interfaith’ and ‘learning objective’. In the search strategy and analysis of this scoping review, we decided not to make a distinction based on the wording of the concept ‘interfaith’ because we aimed to find as many relevant initiatives as possible. In addition, while presented as 12 separate and demarcated learning objectives, some overlap, some cover multiple dimensions, and some are not as coherent as the matrix would suggest. As a result, not each learning objective could be described equally wholly and coherently. More specifically, the attitude learning objectives were often described ambivalently, which prevented a clear definition of terms such as ‘empathy’, ‘appreciation’ and ‘awareness’. We can understand this ambiguity concerning the attitude learning objectives through Spencer’s iceberg model, which explains that attitudes, self-concept, and values are more challenging to identify, assess and develop than knowledge and skills (Spencer and Spencer Citation1993, 11). Therefore, this matrix can be seen as a first framework that must be further defined and clarified.

Furthermore, using the scoping review method has enabled us to collect and analyse the learning objectives of a large diversity of interfaith initiatives. At the same time, however, relevant initiatives outside of bibliographical databases may have been missed. Further research should consider how this matrix relates to initiatives not described in scholarly work in the languages included. Such research should primarily focus on Latin American and other initiatives outside of Europe and the U.S., as these initiatives were under-represented in this scoping review.

As shown in , many initiatives aim to develop participants’ leadership skills, while only a few aim to promote knowledge and awareness about societal issues relating to injustice, power, and privilege. As a result of this imbalance, some organisers may expect participants to improve society and interact with diverse stakeholders without properly examining power and privilege. This observation reflects challenges in the field that have already been acknowledged: ‘there are elements of the [interfaith] movement that fail to address key issues related to religious conflict, prejudice, and oppression’ (Edwards Citation2018, 172). Hence, this scoping review underlines the importance of implementing structural awareness and knowledge about social injustice, power, and oppression in our societies, now and historically, and including them in interfaith learning initiatives.

In conclusion, we recommend that organisers consider the value-laden contexts of their initiatives and avoid implicit and general descriptions in their learning objectives. The matrix of interfaith learning objectives should, therefore, be seen as the first contribution to this recommendation, as an incentive to explicate one’s learning objective and to describe and translate these learning objectives according to the local context of an initiative, and as a stimulus to reflect on the histories and contemporary issues of power, privilege and conflict in interfaith spaces. This article is a first step towards building a shared scholarly framework to guide and support the organisation and evaluation of interfaith initiatives. The matrix can stimulate organisers of interfaith initiatives to clarify their learning objectives and, consequently, develop coherent and evaluable initiatives. In the end, participants of interfaith initiatives will benefit from coherently organised initiatives that can be evaluated and improved.

Acknowledgments

We thank librarian Linda Schoonmade of the VUmc for her role in developing the search strategy of this scoping review. This article was inspired by the pioneering work of setting up a pedagogical framework and conducting empirical research on interfaith competency in the U.S. campus context by the Interfaith Youth Core, the critical exchange on indicators of interfaith success with Katherine O’Lone of the Woolf Institute, and participation in a peer learning community with several interfaith organisations active in DM&E, moderated by the Alliance for Peacebuilding. In the spirit of interfaith work, we look forward to participating in a community of scholars/practitioners to further reflect on the question of how to evaluate interfaith work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hannah J. Visser

Hannah J. Visser is a PhD candidate in interfaith learning at the Faculty of Religion and Theology of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VU). In her research project, she focuses on (the conceptual and empirical nature of) interfaith learning objectives and competencies, and she reflects on the question of how to evaluate participants’ development in interfaith initiatives.

Anke I. Liefbroer

Anke I. Liefbroer is an assistant professor of Psychology of Religion at the Faculty of Religion and Theology of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VU) and the Tilburg School of Catholic Theology. She obtained her PhD degree at VU, focusing on the empirical study of interfaith spiritual care.

Marianne Moyaert

Marianne Moyaert is a full professor of Comparative Theology and Hermeneutics of Interreligious Dialogue at the Faculty of Religion and Theology of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VU). She is also a guest lecturer at the KU Leuven, Belgium, teaching Jewish-Christian relations.

Gerdien D. Bertram-Troost

Gerdien D. Bertram-Troost is a full professor of Religious Education at the Faculty of Religion and Theology of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VU). Her main research interests lie in the fields of education, (developmental) psychology, theology, and their overlap.

Notes

1. The search strategy was determined in consultation with a librarian of the VUmc. The full search strategies for all databases can be found in the Supplementary Information. This information can be requested by the first author.

2. A reflection on the terms and their meaning is beyond the scope of this article. For an elaboration on the distinction between terms such as ‘interfaith’, ‘interreligious’, ‘multifaith’ and ‘religiously diverse’, see for example Longhurst (Citation2020), Miedema (Citation2017), or Swidler (Citation2014). For the differences between terms such as ‘competency’, ‘learning objective’, and ‘outcome’, see for example Hartel and Allen Foegeding (Citation2004), Hoffmann (Citation1999), Hutmacher (Citation1997), or Kennedy, Hyland, and Ryan (Citation2009).

3. These are the languages the authors are familiar with.

5. Some books or articles aim to introduce a scholarly, conceptual debate while others offer practical recommendations for organising an initiative. This confirms the observation of interfaith studies being an interdisciplinary field (Del Vecchio and Silverman Citation2018).

6. We can think of various explanations and considerations regarding the characteristics presented here. A reflection on these characteristics would be an interesting topic for future research.

7. By lived religion, we follow McGuire’s (Citation2008, 3) definition: ‘religion as expressed and experienced in the lives of individuals’.

8. We will further reflect on this observation in the discussion section.

9. Compare the descriptions of perspective taking by Losert, Bräuer, and Schweitzer (Citation2018) and empathy by Cornille (Citation2010).

References

- *Abu-Nimer, M., I. Nasser, and S. Ouboulahcen. 2016. “Introducing Values of Peace Education in Quranic Schools in Western Africa: Advantages and Challenges of the Islamic Peace-Building Model.” Religious Education 111 (5): 537–554. doi:10.1080/00344087.2016.1108098.

- *Acar, E. 2013. “Effects of Interfaith Dialog Activities: The Role of a Turkish Student Association at an East Coast U.S. University.” Educational Research and Reviews 8 (14): 1144–1149. doi:10.5897/ERR2013.1131.

- *Akdag, M., A. Alasag, Ö. Gürlesin, and I. ter Avest. 2019. “Playful Religious Education - Towards Inclusive Religious Education: A Light-Hearted Way for Young People to Develop A Religious Life Orientation.” Studies in Interreligious Dialogue 29 (1): 103–123. doi:10.2143/SID.29.1.3286457.

- *Allen, K. 2016. “Achieving Interfaith Maturity through University Interfaith Programmes in the United Kingdom.” Cogent Education 3 (1): 1261578. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2016.1261578.

- *Ambroson, H. M. 2013. “Increasing Supervisors’ Confidence in the Assessment of Students’ Religious and Spiritual Diversity.” Dissertation, George Fox University.

- *Basham, K., and M. Hughes. 2012. “Creating and Sustaining Interfaith Cooperation on Christian Campuses: Tools and Challenges.” Journal of College and Character 13 (2): 1–7. doi:10.1515/jcc-2012-1900.

- *Beauchamp, M. 2012. “Face to Faith: Teaching Global Citizenship.” Kappan 93 (4): 24–27.

- *Bender-Szymanski, D. 2013. “Argumentation Integrity in Intercultural Education: A Teaching Project about a Religious-ideological Dialogue as Challenge for School.” Intercultural Education 24 (6): 573–591. doi:10.1080/14675986.2013.845932.

- *Bhadra, S. 2018. “Life Skills Education (LSE) in A Volatile Context for Promotion of Peace and Harmony: A Model from Gujarat, India.” In Positive Schooling and Child Development: International Perspectives, edited by S. Deb, 205–232. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- *Bhatia, K. V., and M. Pathak-Shelat. 2019. “Using Applied Theater Practices in Classrooms to Challenge Religious Discrimination among Students.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 62 (6): 605–613. doi:10.1002/jaal.950.

- *Bjork, C. C. S. 2019. Caring for Common Ground: Developing a Spirituality-Based Ecological Restoration Education Program at Holy Wisdom Monastery. Dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- *Bouchard, N. 2009. Living Together with Differences: Quebec’s New Ethics and Religious Culture Program. Education Canada | Canada Education Association 49 (1): 60–62.

- *Brockman, D. R. 2016. “Educating for Pluralism, or Against It? Lessons from Texas and Québec on Teaching Religion in the Public Schools.” Religion & Education 43 (3): 317–343. doi:10.1080/15507394.2016.1147915.

- *Buser, J. K., and T. J. Buser. 2014. “Qualitative Investigation of Student Reflections on a Spiritual/Religious Diversity Experience.” Counseling and Values 59 (2): 155–173. doi:10.1002/j.2161-007X.2014.00049.x.

- *Callahan, A. M., and K. Benner. 2018. “Building Spiritual Sensitivity through an Online Spirituality Course.” Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought 37 (2): 182–201. doi:10.1080/15426432.2018.1445574.

- *Campbell, W., and M. Lane. 2014. “Better Together: Considering Student Interfaith Leadership and Social Change.” Journal of College and Character 15 (3): 195–202. doi:10.1515/jcc-2014-0023.

- *Curpanen, J. R. 2013. “Theological Empowerment: Engaging Laity in Multicultural Marketplace Ministry.” Dissertation, Asbury Theological Seminary.

- *Daddow, A., D. Cronshaw, N. Daddow, and R. Sandy. 2019. “Strengthening Inter-cultural Literacy and Minority Voices through Narratives of Healthy Religious Pluralism in Higher Education.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 25 (10): 1174–1189. doi:10.1080/13603116.2019.1600056.

- *Del Vecchio, K. 2018. “Interreligious Environmentalism: Pragmatic Projects and Moral Competencies that Address Climate Change.” The Journal of Interreligious Studies 22: 46–63.

- *Diaz-Edelman, M. D. 2014. Working Together: Multicultural Collaboration in the Interfaith Immigrant Right Movement. Dissertation, Boston University.

- *Duckworth, C., T. Albano, D. Munroe, and M. Garver. 2019. “‘Students Can Change a School’: Understanding the Role of Youth Leadership in Building a School Culture of Peace.” Conflict Resolution Quarterly 36 (3): 235–249. doi:10.1002/crq.21245.

- *Edwards, S. 2017. “Intergroup Dialogue & Religious Identity. Attempting to Raise Awareness of Christian Privilege & Religious Oppression.” Multicultural Education 24 (2): 18–24.

- *Epstein, N. E. 2018. “Incorporating Religion and Spirituality into Teaching and Practice: The Drexel School of Public Health Experience.” In Why Religion and Spirituality Matter for Public Health: Evidence, Implications, and Resources, edited by D. Oman, 421–433. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- *Ezzani, M., and M. Brooks. 2019. “Culturally Relevant Leadership: Advancing Critical Consciousness in American Muslim Students.” Educational Administration Quarterly 55 (5): 781–811. doi:10.1177/0013161x18821358.

- *Ferreira, C., and S. Schulze. 2016. “Cultivating Spiritual Intelligence in Adolescence in a Divisive Religion Education Classroom: A Bridge over Troubled Waters.” International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 21 (3–4): 230–242. doi:10.1080/1364436X.2016.1244518.

- *Fink, M., L. Linnard-Palmer, B. Ganley, O. Catolico, and W. Phillips. 2014. “Evaluating the Use of Standardized Patients in Teaching Spiritual Care at the End of Life.” Clinical Simulation in Nursing 10 (11): 559–566. doi:10.1016/j.ecns.2014.09.003.

- *Francis, L. J., A. Village, and S. G. Parker. 2017. “Exploring the Trajectory of Personal, Moral and Spiritual Values of 16- to 18-year-old Students Taking Religious Studies at A Level in the U.K.” Journal of Beliefs & Values 38 (1): 18–31. doi:10.1080/13617672.2016.1232567.

- *Francis, L. J., J. Astley, and S. G. Parker. 2016. “Who Studies Religion at Advanced Level: Why and to What Effect?.” Journal of Beliefs & Values 37 (3): 334–346. doi:10.1080/13617672.2016.1236325.

- *Gardner, R. S. 2019. “A Student-Faculty Collaborative Journey toward Transformative Religious and Secular Worldview Literacy.” FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education 5 (1): 126–144. doi:10.32865/fire201951134.

- *Gramstrup, L. K. 2017. “Searching for Interreligious Understanding: Complex Engagements with Sameness and Difference in an American Women’s Interfaith Book Group.” Journal of Beliefs & Values 38 (3): 341–351. doi:10.1080/13617672.2017.1317527.

- *Gramstrup, L. K. 2018. “Blurring Boundaries and Advancing Interreligious Understanding by Engaging Textual ‘Others’ in a Women’s Interfaith Book Group.” Culture and Religion 19 (3): 298–316. doi:10.1080/14755610.2018.1466820.

- *Green, A. R., A. Tulissi, S. Erais, S. L. Cairns, and D. Bruckner. 2018. “Building an Inclusive Campus: Developing Students’ Intercultural Competencies through an Interreligious and Intercultural Diversity Program.” Canadian Journal of Higher Education 48 (3): 43–64. doi:10.47678/cjhe.v48i3.188134.

- *Hayden, J. M. 2010. “Developing Civility at the Deepest Levels of Difference.” About Campus 15 (4): 19–25. doi:10.1002/abc.20031.

- *Hayik, R. 2015. “Addressing Religious Diversity through Children’s Literature: An ‘English as a Foreign Language’ Classroom in Israel.” International Journal of Multicultural Education 17 (2): 92. doi:10.18251/ijme.v17i2.911.

- *Haynes, C. C. 2011. “Putting a Face to Faith.” Educational Leadership 69 (1): 50–54.

- *Helskog, G. H. 2015. “The Gandhi Project: Dialogos Philosophical Dialogues and the Ethics and Politics of Intercultural and Interfaith Friendship.” Educational Action Research 23 (2): 225–242. doi:10.1080/09650792.2014.980287.

- *Herzog, P. S., D. A. T. Beadle, D. E. Harris, T. E. Hood, and S. Venugopal. 2016. “Moral and Cultural Awareness in Emerging Adulthood: Preparing for Multi-Faith Workplaces.” Religions 7 (4): 40. doi:10.3390/rel7040040.

- *Herzog, P. S., D. E. Harris, and J. Peifer. 2018. “Facilitating Moral Maturity: Integrating Developmental and Cultural Approaches.” Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 15 (5): 450–474. doi:10.1080/14766086.2018.1521737.

- *Hicks, M., and U. Tran‐Parsons. 2013. “Spiritual Development as a Social Good.” New Directions for Student Services 2013 (144): 87–95. doi:10.1002/ss.20072.

- *Holden, A. 2013. “Community Cohesion in Post-16 Education: Principles and Practice.” Educational Research 55 (3): 249–262. doi:10.1080/00131881.2013.825162.

- *Holland, C., and M. Walker. 2018. “Choice Theory and Interfaith Dialogue: Building Relationships between Faiths and Embracing Diversity.” International Journal of Choice Theory® and Reality Therapy 37 (2): 17.

- *Hoover, K., and M. Douglas. 2018. “Learning Servant Leadership and Identifying Community-based Strategies in Times of Divide: A Student, Faculty, Community Partner Interfaith Collaboration.” Journal of Leadership Education 17 (2): 83–91. doi:10.12806/V17/I2/A1.

- *Hussien, S., R. Hashim, and N. A. M. Mokhtar. 2017. “Hikmah Pedagogy: Promoting Open Mindedness, Tolerance and Respect for Others’ Religious Views in Classrooms.” In Interfaith Education for All: Theoretical Perspectives and Best Practices for Transformative Action, edited by D. R. Wielzen and I. Ter Avest, 97–106. Rotterdam, the Netherlands: SensePublishers.

- *Jendzejec, E. 2018. “Better Together: Cultivating Interfaith Leadership on College Campuses.” Journal of Catholic Higher Education 37 (2): 253–268.

- *Kilman, C. 2007. “One Nation, Many Gods.” Teaching Tolerance 32: 38–46.

- *Knysh, A., A. Matochkina, D. Ulanova, P. Meechan, and T. Austin. 2019. “When Two Worldviews Meet: Promoting Mutual Understanding between ‘Secular’ and Religious Students of Islamic Studies in Russia and the United States.” In Telecollaboration and Virtual Exchange across Disciplines: In Service of Social Inclusion and Global Citizenship, edited by A. Turula, M. Kurek, and T. Lewis, 57–64. Voillans, France: Research-publishing.net. doi:10.14705/rpnet.2019.35.9782490057429

- *Krebs, S. R. 2015. “Interfaith Dialogue as a Means for Transformational Conversations.” Journal of College and Character 16 (3): 190–196. doi:10.1080/2194587X.2015.1057157.

- *Larson, M., and S. Shady. 2013. “Cultivating Student Learning Across Faith Lines.” Liberal Education 99 (3): 44–51.

- *Lewis, B. 2012. “Teaching Religion in Indonesia: A Report on Graduate Studies in Java.” Teaching Theology and Religion 15 (3): 241–257. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9647.2012.00803.x.

- *Lin, J., S. Edwards, and S. Khami. 2016. “Jewish-muslim Women’s Leadership Initiative: A Program for Peaceful Dialogue.” In Communicating Differences. Culture, Media, Peace and Conflict Negotiation, edited by S. Roy, and I. S. Shaw. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- *Lindsay, J. 2018. “Pluralismo Vivo: Lived Religious Pluralism and Interfaith Dialogue in Rome.” Dissertation, Boston University.

- *Locklin, R. B., T. Tiemeier, and J. M. Vento. 2012. “Teaching World Religions without Teaching ‘World Religions’.” Teaching Theology & Religion 15 (2): 159–181. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9647.2012.00784.x.

- *Long, J. D. 2018. “Site Visits in Interfaith and Religious Studies Pedagogy: Reflections on Visiting a Hindu Temple in Central Pennsylvania.” Teaching Theology & Religion 21 (2): 78–91. doi:10.1111/teth.12427.

- *Luby, A. 2014. “First Footing Inter-faith Dialogue.” Educational Action Research 22 (1): 57–71. doi:10.1080/09650792.2013.854176.

- *Luby, A. 2020. “Initiating the Creation of a Procedurally Secular Society through Dialogic RE. The Three Realms.” Journal of Beliefs & Values 41 (1): 72–87. doi:10.1080/13617672.2019.1613084.

- *Lyndes, K., W. Cadge, and G. Fitchett. 2018. “Online Teaching of Public Health and Spirituality at University of Illinois: Chaplains for the Twenty-First Century.” In Why Religion and Spirituality Matter for Public Health: Evidence, Implications, and Resources, 435–444. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- *Mambu, J. E. 2016. “Investigating Students’ Negotiation of Religious Faiths in ELT Contexts: A Critical Spiritual Pedagogy Perspective.” Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 13 (3): 157–182. doi:10.1080/15427587.2016.1150145.

- *Mardell, B., and M. M. Abo-Zena. 2010. “‘The Fun Thing about Studying Different Beliefs Is That … They are Different’: Kindergartners Explore Spirituality.” YC Young Children 65 (4): 12–17.

- *Mason, J. 2016. “Telecollaboration as a Tool for Building Intercultural and Interreligious Understanding: The Sousse-Villanove Programme.” In New Directions in Telecollaborative Research and Practice: Selected Papers from the Second Conference on Telecollaboration in Higher Education, edited by S. Jager, M. Kurek, and B. O’Rourke, 267–273. Voillans, France: Research-publishing.net.

- *Mayer, C.-H., R. Viviers, A.-P. Flotman, and D. Schneider-Stengel. 2016a. “Enhancing Sense of Coherence and Mindfulness in an Ecclesiastical, Intercultural Group Training Context.” Journal of Religion and Health 55 (6): 2023–2038. doi:10.1007/s10943-016-0301-0.

- *Mayer, C.-H., R. Viviers, A.-P. Flotman, and D. Schneider-Stengel. 2016b. “A Longitudinal Case Study: The Development of Exceptional Human Experiences of Senior Ecclesiastical Professionals in the Catholic Church.” Journal of Religion and Health 55 (6): 2010–2022.

- *McCarthy, K. 2007b. “Meeting the Other in Cyberspace: Interfaith Dialogue Online.” In Interfaith Encounters in America, edited by K. McCarthy, 169–197. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- *McCarthy, K. 2007c. “Strange Bedfellows: Multifaith Activism in American Politics.” In Interfaith Encounters in America, edited by K. McCarthy, 45–83. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- *McCowan, T. 2017. “Building Bridges Rather than Walls: Research into an Experiential Model of Interfaith Education in Secondary Schools.” British Journal of Religious Education 39 (3): 269–278. doi:10.1080/01416200.2015.1128387.

- *McMinn, M. R., R. K. Bufford, M. J. Vogel, T. Gerdin, B. Goetsch, M. M. Block, J. K. Mitchell, et al. 2014. “Religious and Spiritual Diversity Training in Professional Psychology: A Case Study.” Training and Education in Professional Psychology 8 (1): 51–57. doi:10.1037/tep0000012.

- *Miles, J. R., and B. Mallinckrodt. 2017. “Establishing a Secure Base to Increase Exploration of Diversity in Groups.” International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 67 (2): 259–275. doi:10.1080/00207284.2016.1264721.

- *Miller, S., J. Rothman, B. Ciaravolo, and S. Haney. 2012. “Embedding Action Evaluation in an Interfaith Program for Youth.” In From Identity-Based Conflict to Identity-BasedCooperation: The ARIA Approach in Theory and Practice, edited by J. Rothman, 175–189. New York: Springer New York.

- *Mohamed, C. 2019. “The Challenge of Shaping Socially Responsible Teachers.” Education 3-13 47 (1): 74–88. doi:10.1080/03004279.2017.1404118.

- *Mohammed-Ashrif, F. 2018. “Visions of Beauty.” Crosscurrents 68 (3): 358–371. doi:10.1111/cros.12318.

- *Moyaert, M. 2017. “Ricoeur, Interreligious Literacy, and Scriptural Reasoning.” Studies in Interreligious Dialogue 27 (2): 3–26. doi:10.2143/sid.27.2.3269033.

- *Naumenko, E. A., and O. N. Naumenko. 2016. “Pedagogical Experience on Formation of Tolerant and Multicultural Consciousness of Students.” European Journal of Contemporary Education 17 (3): 335–343.

- *O’Keefe, T. 2009. “Learning to Talk: Conversation across Religious Difference.” Religious Education 104 (2): 197–213. doi:10.1080/00344080902794665.

- *Pallavicini, Y. S. Y. 2016. “Interfaith Education: An Islamic Perspective.” International Review of Education/Internationale Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft/Revue Internationale de l’Education 62 (4): 423–437.

- *Patel, E., and C. Meyer. 2012. “Interfaith Leaders as Social Entrepreneurs.” Journal of College and Character 13 (4): 1–9. doi:10.1515/jcc-2012-1949.

- *Pearce, M. J., K. I. Pargament, H. K. Oxhandler, C. Vieten, and S. Wong. 2020. “Novel Online Training Program Improves Spiritual Competencies in Mental Health Care.” Spirituality in Clinical Practice 7 (3): 145–161. doi:10.1037/scp0000208.

- *Poppinga, A., M. Larson, and S. Shady. 2019. “Building Bridges across Faith Lines: Responsible Christian Education in a Post-Christian Society.” Christian Higher Education 18 (1–2): 98–110. doi:10.1080/15363759.2018.1542906.

- *Proehl, R. A. 2012. “Protecting Our Elders: An Interfaith Coalition to Address Elder Abuse.” Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging 24 (3): 249–266. doi:10.1080/15528030.2012.638249.

- *Ramarajan, D., and M. Runell. 2007. “Confronting Islamophobia in Education.” Intercultural Education 18 (2): 87–97. doi:10.1080/14675980701327197.

- *Shadbolt, C. 2017. “Dancing in a Different Country: When the Personal Is Professional.” Transactional Analysis Journal 47 (4): 264–275.

- *Sloan-Power, E. 2013. “Diversity Education and Spirituality: An Empirical Reflecting Approach for MSW Students.” Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought 32 (4): 330–348. doi:10.1080/15426432.2013.839222.

- *Stoltzfus, M. J., and J. A. Raffel. 2009. “Cultivating an Appreciation for Diverse Religious Worldviews through Cooperative Learning in Undergraduate Classrooms.” Religious Education 104 (5): 539–554. doi:10.1080/00344080903293998.

- *Tyler, C., L. Valek, and R. Rowland. 2005. “Graphic Facilitation and Large-Scale Interventions: Supporting Dialogue between Cultures at a Global, Multicultural, Interfaith Event.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 41 (1): 139–152. doi:10.1177/0021886304272850.

- *Warner, K. D., A. Brook, and K. Shaw. 2012. “Facilitating Religious Environmentalism: Ethnology Plus Conservation Psychology Tools Can Assess an Interfaith Environmental Intervention.” Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture, and Ecology 16 (2): 111–134. doi:10.1163/156853512X640833.

- *Weller, P. 2017. “Learning from Experience, Leading to Engagement: Lessons from Belieforama for a Europe of Religion and Belief Diversity.” Studies in Interreligious Dialogue 27 (2): 27–51. doi:10.2143/sid.27.2.3269034.

- *Wilson, R. J., F. Y. Abram, and J. Anderson. 2010. “Exploring a Feminist-based Empowerment Model of Community Building.” Qualitative Social Work 9 (4): 519–535. doi:10.1177/1473325009354227.

- *Yuskaev, T. R. 2013. “Staying Put: Local Context as Classroom for Multifaith Education.” Teaching Theology & Religion 16 (4): 362–370. doi:10.1111/teth.12137.

- *Zain, A., M. Daima, M. S. Ali, S. H. Syed Omar, and W. M. K. F. Wan Khairuldin. 2018. “The Role of Comparative Religion Course in Unisza in Forming Interreligion Dialogue among Students.” International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology 9 (13): 186–193.

- Abu-Nimer, M. et al 2021. ”Challenges in Peacebuilding Evaluation. Voices from the Field.” In Evaluating Interreligious Peacebuilding and Dialogue. Methods and Frameworks, edited by M. Abu-Nimer, and R. K. Nelson, 25–51. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110624625-002

- Albarracín, D., B. T. Johnson, M. P. Zanna, and G. Tarcan Kumkale. 2005. “Attitudes: Introduction and Scope.” In The Handbook of Attitudes, edited by D. Albarracín, B. T. Johnson, and M. P. Zanna, 3–19. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Berling, J. A. 2020. “Developing Pedagogies of Interreligious Understanding.” In Critical Perspectives on Interreligious Education, edited by N. Syeed, and H. Hadsell, 1–12. Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- Biggs, J. 1996. “Enhancing Teaching through Constructive Alignment.” Higher Education 32 (3): 347–364. doi:10.1007/BF00138871.

- Biggs, J. 2003. “Aligning Teaching and Assessment to Curriculum Objectives.” Imaginative Curriculum Project, LTSN Generic Centre, 12.

- Bloom, B. S. 1956. Taxonomy of educational objectives. Vol. 1: Cognitive domain. New York: McKay.

- Byrne, C. 2011. “Freirean Critical Pedagogy’s Challenge to Interfaith Education: What Is Interfaith? What Is Education?” British Journal of Religious Education 33 (1): 47–60. doi:10.1080/01416200.2011.523524.

- Cheetham, D., D. Pratt, and D. Thomas. 2013. Understanding Interreligious Relations. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Chlopan, B. E., M. L. McCain, J. L. Carbonell, and R. L. Hagen. 1985. “Empathy: Review of Available Measures.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48 (3): 635–653. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.48.3.635.

- Cornille, C. 2010. “Empathy and Inter-religious Imagination.” In Traversing the Heart: Journeys of the Inter-religious Imagination, edited by R. Kearney and , and E. Rizo-Patron, 107–121. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Davis, M. H. 1996. Empathy: A Social Psychological Approach. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Del Vecchio, K., and N. J. Silverman. 2018. “Learning from the Field: Six Themes from Interfaith/interreligious Studies Curricula.” In Interreligious/Interfaith Studies: Defining a New Field, edited by E. Patel, J. H. Peace, and N. J. Silverman, 49–57. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Eck, D. L. 2003. Encountering God: A Spiritual Journey from Bozeman to Banaras. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Edwards, S. 2018. “Critical Reflections on the Interfaith Movement: A Social Justice Perspective.” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 11 (2): 164–181. doi:10.1037/dhe0000053.

- Garfinkel, R. 2004. “What Works? Evaluating Interfaith Dialogue Programs.” In Special Report, 1–12. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace.

- Griera, M., and A.-K. Nagel. 2018. “Interreligious Relations and Governance of Religion in Europe: Introduction.” Social Compass 65 (3): 301–311. doi:10.1177/0037768618788274.

- Grimmitt, M. 1987. “Religious Education and Value Assumptions.” British Journal of Religious Education 9 (3): 160–170. doi:10.1080/0141620870090308.

- Grimmitt, M. 1994. “Religious Education and the Ideology of Pluralism.” British Journal of Religious Education 16 (3): 133–147. doi:10.1080/0141620940160302.

- Halafoff, A. 2013. The Multifaith Movement: Global Risks and Cosmopolitan Solutions. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

- Halsall, A., and B. Roebben. 2006. “Intercultural and Interfaith Dialogue through Education.” Religious Education 101 (4): 443–452. doi:10.1080/00344080600948571.

- Hartel, R. W., and E. Allen Foegeding. 2004. “Learning: Objectives, Competencies, or Outcomes?” Journal of Food Science Education 3 (4): 69–70. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4329.2004.tb00047.x.

- Hodge, D. R. 2018. “Spiritual Competence: What It Is, Why It Is Necessary, and How to Develop It.” Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work 27 (2): 124–139. doi:10.1080/15313204.2016.1228093.

- Hoffmann, T. 1999. “The Meanings of Competency.” Journal of European Industrial Training 23 (6): 275–286. doi:10.1108/03090599910284650.

- Hutmacher, W. 1997. “Key Competencies in Europe.” European Journal of Education 32 (1): 45–58.

- Kennedy, D., Á. Hyland, and N. Ryan. 2009. “Learning Outcomes and Competences.” Introducing Bologna Objectives and Tools 3: 1–18.

- Longhurst, C. E. 2020. “Interreligious Dialogue? Interfaith Relations? Or, Perhaps Some Other Term?” Journal of Ecumenical Studies 55 (1): 117–124. doi:10.1353/ecu.2020.0001.

- Losert, M., M. Bräuer, and F. Schweitzer. 2018. “Interreligious Learning through Perspective-taking: An Intervention Study.” In Researching Religious Education: Classroom Processes and Outcomes, edited by F. Schweitzer, and R. Boschki, 209–244. Münster, Germany: Waxmann.

- Mayer, J. D., and P. Salovey. 1993. “The Intelligence of Emotional Intelligence.” Intelligence 17 (4): 433–442. doi:10.1016/0160-2896(93)90010-3.

- McCallum, R. 2018. “Towards a Framework and Methodology for the Evaluation of Inter-faith Initiatives.” Studies in Interreligious Dialogue 27 (1): 63–81. doi:10.2143/sid.27.1.3275092.

- McCarthy, K. 2007a. Interfaith Encounters in America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- McGuire, M. B. 2008. Lived Religion: Faith and Practice in Everyday Life. Oxford, UK/New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Miedema, S. 2017. “The Concept and Conceptions of Interfaith Education with Neighbour Concepts.” In Interfaith Education for All, edited by D. Wielzen, and I. ter Avest, 21–30. Rotterdam, the Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

- Patel, E., and C. Meyer. 2011. “The Civic Relevance for Interfaith Cooperation for Colleges and Universities.” Journal of College and Character 12 (1). doi:10.2202/1940-1639.1764.

- Pedersen, K. P. 2004. “The Interfaith Movement: An Incomplete Assessment.” Journal of Ecumenical Studies 41 (1): 74–94.

- Peters, M. D. J., C. M. Godfrey, H. Khalil, P. McInerney, D. Parker, and C. B. Soares. 2015. “Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews.” International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13 (3): 141–146. doi:10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050.

- Pollefeyt, D. 2020. “Hermeneutical Learning in Religious Education.” Journal of Religious Education 68 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/s40839-020-00090-x.

- Schwandt, T. A. 1999. “On Understanding Understanding.” Qualitative Inquiry 5 (4): 451–464. doi:10.1177/107780049900500401.

- Seyle, C., S. Heyborne, J. Baumgardner-Zuzik, and D. Shaziya. 2021. Some Credible Evidence: Perception about the Evidence Base in the Peacebuilding Field. One Earth Future Foundation; The Alliance for Peacebuilding.

- Sorensen, N., B. A. Nagda, P. Gurin, and K. E. Maxwell. 2009. “Taking a ‘Hands On’ Approach to Diversity in Higher Education: A Critical-Dialogic Model for Effective Intergroup Interaction.” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 9 (1): 3–35. doi:10.1111/j.1530-2415.2009.01193.x.

- Spencer, L. M., and S. M. Spencer. 1993. Competence at Work: Models for Superior Performance. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Swidler, L. J. 2014. “Which Word(s) to Choose: Ecumenical, Interreligious, Interfaith … ?.” Journal of Ecumenical Studies 49 (1): 184–188.

- Vader, J. 2015. Meta-review of Inter-religious Peacebuilding Program Evaluations. CDA Collaborative Learning Projects.