ABSTRACT

There is a deficit in character education research in Latin America and a lack of clarity about conceptual issues relevant to values and virtues. This lack of conceptual clarity has practical importance. The research sought to investigate empirically how school managers and teachers understand and practice character education, with particular attention to the distinction between educating values and virtues. The study was carried out during the first semester of 2022 on a sample of 160 schools in 17 countries, mainly in Christian schools in Spain and Mexico. The results show that there are differences according to the type of school and country. There are important findings regarding the concept of virtue and its relation to the concept of value, which virtues and values are most relevant for schools to teach, and which are the most used strategies in character education programmes. The research points to moral education as a central theme in schools, which considers both virtue and values education. There is a genuine interest on training teachers in virtue education.

SUMMARY

The study contributes to a better comprehension of moral education (particularly in character education) in Spain and Latin America. It provides an understanding of the differences and similarities between virtue and values education in the minds of educators. It offers information on the main practical strategies linked to character education as well as reflections on how to carry out character education in Latin America.

Finally, the study offers a comparison between the paradigm of virtue education and the paradigm of values education that can be inferred from the responses of school managers and teachers. These are two competing but compatible paradigms of moral education. Our proposal is that there should be a constructive dialogue between paradigms and even a synthesis.

Introduction

The study aims to identify what school managers and teachers understand by education in virtues and values, whether they find differences in it, and to find out which virtues they consider most relevant in their schools when it comes to educating.

The specific objectives were to find out:

The concept of virtue held by school managers and teachers, its relationship with the concept of value and whether these are compatible for them.

Whether schools have an ‘education in virtues programme’ and, if so, which strategies are most used for teaching them, as well as the educational agents involved.

Which virtues are commonly taught in schools, and whether civic virtues are taught at the initiative of the public administration.

The importance given to virtue education and teacher training in this area.

Whether there are significant differences according to certain classificatory variables: country, ownership of the school, religious principles of the institution.

There is little research on moral education in Latin America, particularly on character education in schools, compared to United States (Pattaro Citation2016). Studies on principals’ conceptions of character education suggest that in Spain, Argentina, Colombia and Mexico, character education is conceived as a subject linked more to education in values than in virtues (Bernal et al., Citation2017).

In Colombia, Chile and Mexico, values education has been promoted as part of a competency-based curriculum (Conde-Flores, García-Cabrero, and Alba-Meraz Citation2017; Velásquez et al. Citation2017) through an optional subject; its implementation has been difficult due to the social and cultural context of the country, and to challenges from teachers’ unions.

A comparative study of civic education between Mexico, Chile and Colombia shows better results in Chile, although the differences may be linked not so much to the programme, but to the characteristics of the school and the socio-economic level of the students (Treviño et al. Citation2017).

Spanish and Portuguese educational legislation on education reflects a change of mentality or paradigm in favour of education in values (instead of virtues), starting in the 1980s based on the indications of the European Union (EU Communities Citation2006, Citation2007; Fuentes Citation2018; Gomes-Dias and Hortas Citation2020). It is worth mentioning that the model of competences for citizenship includes, primarily, values, as well as skills, attitudes, and knowledge (Consejo de Europa Citation2018).

One explanation for the paradigm shift in Spain and Portugal (linked to values education) may lie in the rejection of the political regime that once promoted virtue education with the support of the Catholic Church (Lopes et al. Citation2013). Virtue education or character education is rejected because of its link to autocratic and outdated political regimes. It is also considered to be used to stress individual differences, as well as to justify discrimination and a certain supremacy of some over others (Kirchgasler Citation2018). In any case, the paradigm of value education, particularly civic values (considered as competences or competency components) predominate in these countries.

This does not mean that students in Ibero-American countries are not being educated in virtues today, but that virtues are not mentioned as a learning objective or outcome. The word ‘virtue’ seems to be politically incorrect. Interestingly, in the case of Colombia, education in the value of citizenship is in fact linked to a character education programme, although this term never appears (Berkowitz & Bustamante, Citation2013).

Each paradigm – value education and virtue education, in this case – responds to an underlying philosophy about what kind of person to educate, methodological preferences, what values or virtues to educate and how to do it (Berkowitz Citation2002).

Without denying the differences, is a reconciliation possible? In our view, despite the differences and the existing struggle, there are common elements that allow for reconciliation (Berkowitz Citation2002; Althof and Berkowitz Citation2006; Burgos Citation2013; Nucci, Narvaez, and Krettenauer Citation2014; Peterson Citation2020) and mutual enrichment.

The values education paradigm has at its core a stream that, based on Piaget and Kohlberg, seeks the cognitive and moral development of students with an emphasis on reasoning; but it also includes civic education for citizenship (Taylor Citation1994; Thornberg and Oğuz Citation2016). Although Kohlberg disdained virtue education as arbitrary and ungrounded in research -what he called the ‘virtue bag’ (Kohlberg and Mayer Citation1972, 478; Linde Citation2010) – it is unquestionable that in his proposal there is a consideration of the virtue of justice and relational maturity as expressions of moral development. One can even discover in his writings an attempt to link himself to the educational tradition of Plato, defender of moral virtues (Kohlberg and Mayer Citation1972). In this paradigm, virtue and values have a commonality in the behaviour learnt by children and in their maturing rationality.

Even if values and virtues are considered as different concepts for educators, they are intimately related in moral action and in moral development, both in theory and in practice, as discussed below. This close relationship explains why for many teachers or school managers virtues and values are a similar concept. The aim is to offer a theoretical framework that can integrate virtues and values while respecting their differences. Something has ‘value’ when we discover a quality in a being that we consider estimable, valuable. Values refer to objective properties of being that, when recognised by a person, are estimated as valuable, as something good. Values have an objective foundation that is subjectively known, although in some specific cases the subject can be deceived and recognise as an apparent value, something without any value (Guardini Citation1999). For his part, Ortega y Gasset (Citation2004) agrees on the objectivity of values and the subject’s estimative capacity to appreciate them. The knowledge of values is reached through experience and practice (Spaemann Citation1987), without denying the value of theoretical knowledge or moral reasoning. The values that we discover with the intelligence are at the same time desired as goods by the will and desired by the affectivity of the person. This desire for a good triggers human action and accompanies it (De Finance Citation1966; Bosch Citation2020). The practice of the good leads the person to develop the capacity or habitual disposition to act well, i.e. to virtue, according to the Aristotelian perspective.

There is also evidence that teachers, are eclectic in their use of these paradigms or in linking to these traditions (Revell and Arthur Citation2007; Thornberg and Oğuz Citation2016). Moral reasoning, a central element of values education, not only does not run counter to virtue education, but correlates positively (Arthur et al. Citation2015) and helps to address moral emotivism (Marulanda, Citation2012).

Therefore, education in values and education in virtues can be distinguished, but not separated. Whenever one educates in virtues, one also educates in values and vice versa. Education is a secondary effect on the very character of the person (Spaemann Citation2003, 479).

Moral education helps the subject to discover and guide his or her actions towards values by considering their hierarchy: practical wisdom (or prudence) enables him or her to order his or her actions appropriately. It should not only be an education focused on cognitive and normative aspects or values, but also on affection and virtues (Lickona Citation1991; Melina, Noriega and Pérez-Soba Citation2007); it requires a pedagogy of desire whereby the person, attracted by a good, strives to act in accordance with that value and enjoys doing so. In the Aristotelian perspective, rationality, and desire (orexis) interact in human action: it is not enough to know. It is desire, not so much the intellect, which guides us towards ends or purposes, but without this being arbitrary: we desire what we recognise as good and true. Doing and desiring go together (Bastons Citation2020).

Education is a side effect on the very character of the person (Spaemann Citation2003, 479). The virtues are not the goal of our actions, but they are the fruit and condition for reaching the ultimate end, which is communion with God and with others. Full human flourishing consists precisely in communion.

We assume that an education in virtues and values is possible, which distinguishes, without opposing, the two concepts or paradigms. Certainly, these distinctions are not always clear in the minds of educators or in educational programmes that aim at education in virtues and values.

Methodology

Participants

The study population was 160 schools in seventeen countries. 160 representatives (school managers or teachers) answered the survey, corresponding to each of the participating schools. Due to the difficulties in obtaining a representative sample of schools (both by country and by type of school), it was necessary to opt for a convenience sampling with the schools we work with and that have a relation with our university because it was the only way we had to drum up participants. The sampling does not allow the results to be generalised but do offer valuable information to formulate hypotheses. The sample obtained allows us to explore the understanding and practice of character education in Christian schools (133 out of 160), particularly those in some countries such as Mexico (49 out of 160) and Spain (61 out of 160).

Of the 160 representatives surveyed for each school, 27.5% were male and 72.5% female. 63.7% are school managers and 36.3% are only teachers; 61.9% have more than 11 years of experience in education as shown in the .

Table 1. Distribution of the sample according to years of experience.

Table 2. Sample distribution according to years of experience and current institutional position.

Characteristics of the type of schools

In terms of the type of schools represented in the sample, 65.6% are private schools with Christian school principles; 8.1% of the schools are public schools and 13.8% are schools without Christian school principles as shown in .

Table 3. Distribution of the sample according to ownership and principles of the school.

The schools studied are from seventeen different countries, mainly from Spain (38.1%), Mexico (30.6%) and the United States (7.5%) as shown in .

Table 4. Distribution of the sample according to the nationality of the educational institution.

Instruments and variables

The following socio-demographic variables were included for consideration in the study: Sex (male or female); Time as a teacher (less than 5 years; between 6 and 10 years; more than 11 years); Role in the school (teacher or manager); Name of the school. We also considered as socio-demographic variables: The ownership of the school (public, private or charter); Country and, finally, the type of school principles (religious or not).

The complete questionnaire can be found in Appendix A. Except for the question on the concept of virtue education, the rest of the variables could be coded, and their frequency analysed.

Data collection

Data collection was conducted through a questionnaire created in Google Forms addressed to school managers and teachers from elementary school to high school level, with open and closed questions. The questionnaire was written in Spanish, English, Italian and French. The data collection was conducted during the months of January to March 2022. The link and an invitation to answer the questionnaire, was passed via email to a database of schools linked to the Francisco de Vitoria University which is a Catholic university located in Spain and linked, in a particular way, to Mexico and Chile.

The name of the school was requested to verify that there were no duplicate schools in the responses.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis of the variables were conducted. An inferential analysis was performed using contingency tables with chi-square to evaluate whether there was independence between some of the target variables of our research. Analysis were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistic v.21. For the qualitative part, a frequency analysis of the concepts and key words was performed according to the research objectives. The graphical representation of the qualitative analysis was done using Atlas.ti 9.

Results

Regarding the characterisation of virtue education in this sample of schools, the results obtained are as follows:

A large majority of schools do have a programme for virtue education (84.7%). These programmes are not the result of a requirement of the public administration (only 16.3% of the schools indicate this requirement of the governmental authority), but of the school’s own initiative. 83.1% of the schools promote virtue formation among peers, i.e. among pupils. 100% of respondents indicated the importance of teacher training in this area.

The results showed statistically significant differences between the type of school (private, public and charter) and having a formal virtue education programme (χ2(2) = 27.3, p < .001). Public schools do not usually have a formal programme of education in virtues, unlike private or charter ones.

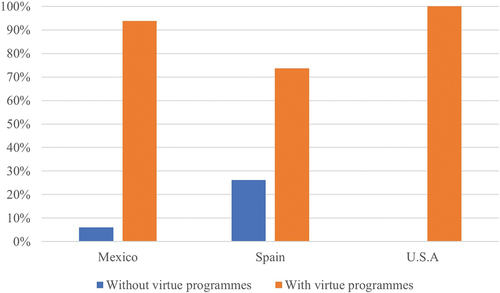

Regarding the existence of virtue education programmes in different countries, considering the countries with a sufficiently large sample (Mexico, Spain, and the USA), significant differences were found (χ2(2) = 10.8, p < .004) with respect to the existence of a virtue programme, as shown in .

In terms of schools with Christian principles and a virtues programme, the result was also statistically significant (χ2(1) = 18.1, p < .001). 7.6% of schools with a Christian ethos reported not having a formal virtue education programme compared to 40% of schools with a non-Christian ethos.

Non statistically significant differences were found between question 9 and the type of school, (χ2(6) = 11.06, p < .071), country, (χ2(48) = 43.3, p < .664), school principles, (χ2(3) = 0.252, p < .969) and, p < .380), neither with question 13 and the type of school (χ2(4) = 2.21, p < .697), country (χ2(32) = 39.0, p < .183), and school principles (χ2(2) = 1.60, p < .450).

Question 16 does not have sufficient variability in the answers, so an inferential analysis with chi-square was not appropriate.

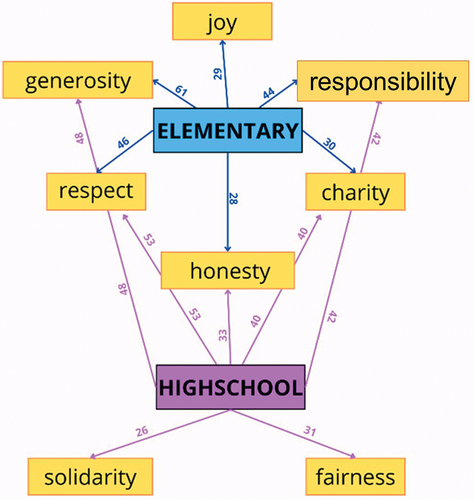

As for the main virtues taught in the different schools, we have differentiated them by educational level: elementary school and middle/high school.

In elementary schools, the most frequently mentioned virtues are shown below in .

Table 5. Virtues most promoted in primary school.

We proceeded to group the virtues by areas based on the meta-model of López and Ortiz de Montellano (Citation2021) where virtues are divided for their education into three areas: 1) relational virtues (whose area of application is the relationship with others); 2) performance virtues (those oriented to the performance of tasks); 3) intellectual virtues (those whose main area is the understanding of reality); 4) Theological virtues (whose scope is linked to divinity) were added. shows the data according to this grouping criterion, leaving nine words ungrouped (because they do not clearly correspond to any group) out of a total of 763 that have been mentioned.

Table 6. Grouping by domains of the virtues mentioned in primary education.

For middle/high schools, 777 words were mentioned as virtues worked on in schools. The most promoted virtues are listed as follows in :

Table 7. Most promoted virtues at middle/high school level.

Grouping the virtues mentioned in middle/high schools with the same criteria used for elementary schools, we can see the results in the following table. Out of a total of 778 virtues mentioned, 769 were classified, leaving nine ungrouped as shown in .

Table 8. Grouping by domains of the virtues mentioned in middle/high school education.

Of the most frequently mentioned virtues in both elementary and middle/high school education, there is agreement on the following: generosity, responsibility, charity, honesty, and respect. Joy is only proposed for primary school, while solidarity and justice are only proposed for middle/high school as shown in .

Figure 2. Similarities and differences in virtues promoted at elementary and middle/high school level.

Civic virtues most promoted at school are as follow in :

Table 9. Civic virtues most promoted at school.

Question 11 and question 8 point to the respondents’ concept of moral education in virtues and values.

The majority consider virtues and values to be different concepts (60.1%), although for a significant group they are the same (22.5%). A not small group considers that even though they are different, they are similar (14.4%).

Analysing the content of the responses, it is possible to identify three basic distinctions that express the difference between virtues and values according to our respondents. The first is that virtues are internal, and values are external (25 times). The second distinction is that values are attitudinal or cognitive and virtues are operational (47 times). The third is that virtues are Christian, and values are secular (8 times). In we can see some examples.

Table 10. Differences between virtues and values according to respondents.

From the responses we can identify two approaches or paradigms that are present in our sample: an approach that stresses the importance of virtues in moral education and other that stresses the importance of civic values related to cognitive and social development.

In classifying the responses -based on the differences in terms of terminological preferences- we found that 126 of the respondents assumed the virtue education approach, while twenty-eight followed value education approach. It was not possible to classify the answers of the remaining respondents (6) as they did not give a clear answer.

Each paradigm prefers certain terms. The answers of the respondents who assume the virtue education paradigm, tend to use words such as habitus (36 times) while, those followers of the value education paradigm, hardly mention it (1 time). Something similar happens with the word formation (41 vs. 1), integral (23 vs. 0) and Christ or Gospel (13 vs. 0). The word development, on the other hand, is proportionally more used in the value education paradigm (it appears in 21.4% of the responses) than in the virtue education approach (it appears in only 13.4% of the responses). We did not find a significant preference for the word value or values in either paradigm: in the value education paradigm it appears seven times, while in the virtue education paradigm it appears thirty-two times. Similarly, the word ‘educate’, or ‘education’ appears 49 times in the virtue education approach and 13 times in the value education paradigm, which does not imply a significant difference if we consider the sample sizes. Examples are given below in .

Table 11. Terminological preferences and differences between virtue and value education.

Another aim of the study was to identify the most important actors in virtue education. Respondents’ answers to question 14, grouped by categories, allow us to identify five types of agents who play a significant role in virtue education: teachers, non-teaching staff, pastoral team, family members and students as shown in .

Table 12. Key actors in virtue education.

The teacher is considered the most relevant agent of virtue education.

Another objective of the research was to identify the most used practices in virtue education. The most relevant were divided into the following categories as shown in :

Table 13. Most relevant virtue education practices.

The most used are the so-called experiential ones as well as campaigns and competitions; and the least used are the so-called spiritual ones.

Discussion

The information collected clearly shows that the representatives that were surveyed consider virtue education to be of greater importance. Although education authorities promote the values education paradigm, omitting to mention virtues, most schools (84.7%) have a virtues education programme, compatible with values education, in which experiential practices predominate. Kolb’s (Citation2015) educational model of experiential learning has a certain affinity.

It is also reasonable that since Latin America (in particular Mexico) is a region with a Christian tradition, there is a great vitality in terms of education in virtues. Christian educational institutions, according to some studies, are more likely to assume a model or paradigm of virtue education and for their teachers to assume a moral role towards their students (Revell and Arthur Citation2007). It is not surprising, therefore, that in the sample of schools studied (mostly Christian-inspired) we find interest in virtue education.

Other important finding is the concept of virtue and the concept of value that school managers express in their responses. The values are more related to the attitudes and reasoning of the person while the virtues are considered more linked to the person’s way of being and acting.

As for the virtues most frequently mentioned, it is interesting to compare this finding with those of the VIA Youth Survey (VIA-YS). According to this study, gratitude, good humour, and love are the most developed virtues in the opinion of the young people themselves. The least developed are prudence, forgiveness, religiosity (or spirituality) and self-regulation (Park, Peterson and Seligman Citation2006). Good humour does not appear, and gratitude occupies an intermediate position. Instead, temperance and responsibility are more prominent. One explanation may lie in who answers the questionnaires: in our sample it is the school managers and teachers, while in the VIA-YS sample it is the young people themselves who answer the questionnaires. In any case, our study confirms the importance given to relational virtues, especially in middle/high school, above operational and intellectual virtues. As in the VIA-YS, it is striking how little mention is made of intellectual virtues.

The most frequently mentioned civic virtues are respect, solidarity, and responsibility. There is a remarkable coincidence with virtues promoted in schools linked to character education programmes in the United States (Lickona Citation1996).

It is important the finding regarding the differences between schools (in different countries and their principles) and the existence of formal or non-formal programmes of virtue education. Spain seems to be the country where formal virtue education programmes are least implemented. This can be explained by the effect of secularisation in culture and the view of character education as outdated.

As for the concept of virtues and values, the results indicate that these concepts are close and linked to each other according to the respondents. Educating in virtues implies educating in values, and vice versa. Certainly, differences are noted (e.g. virtues are more interior and at the same time have to do with action, while values are more attitudinal and cognitive) but they are not opposed to each other. The responses express that there is no rejection between paradigms but that school managers, even recognising differences and having their preferences, seek to integrate both approaches in moral education.

The most practised virtues point to the relational domain, which responds to the fact that the school interacts with people all the time. Our research recognises the importance of these virtues, particularly the so-called ‘civic’ virtues. The scarce presence of intellectual virtues is striking, as is the lack of reference to the theme of truth and goodness. Moral reasoning, which is being neglected, should be promoted. It is therefore necessary to recover phronesis or practical wisdom, i.e. to educate in prudence in all its dimensions and expressions.

The research points in this direction: moral education is a central issue in schools, which considers both virtues and values education, particularly in Christian schools. In general, education in virtues is intentional and it is organised through a specific work programme with concrete strategies and practices. In this intentional effort to educate in virtues, the whole community has an educational role, but the main agents are the teachers. They are undoubtedly expected to provide education in virtues and not only academic or competence teaching. Their training is key.

In certain virtue education proposals, there may be an excessive preoccupation with external behaviours, judging by some of the respondents’ answers. It is a contradiction because virtue education should be oriented towards the interiority of the person: the intentionality of a good and the priority of being over making. Education in virtues needs to be purified of an inappropriate behaviourist bias.

Although teacher training in virtues is considered essential (100% responses say so), the reality in Ibero-America shows that there is little teacher training available in this area (Fuentes Citation2018).

Public policies in virtues education are not particularly relevant according to the respondents. Perhaps the answers are biased and in fact they do have an influence, but we have not been able to find evidence of this.

Conclusions

There is a genuine interest on virtue education and training teachers in virtue education. A large majority of schools (not only Christian) have intentional activities or programmes to educate in virtues or values. We can observe that for most respondents virtues and values are different concepts, however, a significant percentage consider them to be similar. Although they are different concepts, they are not opposed to each other, but rather complement each other, both in theory and in practice.

The character or virtue education paradigm proposed is more practically oriented, whereas the value education paradigm is more attitudinal and intellectual. All these elements (cognitive, affective, practical) are needed for an adequate education in virtue.

For the future, it would be useful to apply the survey to a larger and more universal sample of countries and types of schools, to be able to better compare the differences. The limitations of the sample do not allow conclusions but offer exploratory hypotheses. In particular, the sample should include more public and non-denominational schools.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Verónica Fernández Espinosa

Verónica Fernández Espinosa Dr. is a professor at the Universidad Francisco de Vitoria (UFV) and coordinator of the Seminar on Faith & Science Dialogue in Education. She is the international head of the school’s area of the RC Schools Network. She has worked for more than twenty years in the educational field where she has also been director of schools for several years. She has experience in team building and management in educational institutions at national and international level. Her current teaching practice and research focuses on educational leadership and virtue ethics applied to education. She is a consultant for the Valued Based Leadership project run by the Oxford Character Project at Oxford University and collaborates with the European Character and Virtue Association and the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues. She also collaborates with the Joint Diploma Leadership Service Through Virtues (LSTV) of the Open Reason Institute and the Pontifical Universities of Rome. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6335-1372; https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=YJWGolcAAAAJ&hl=es; https://www.linkedin.com/in/verof1/

Jorge López González

Jorge López González Dr. is the current Dean of the Faculty of Education and Psychology at Universidad Francisco de Vitoria (UFV). He has been rector of the Universidad Anáhuac México Sur, lecturer, and doctor in Administration from the Universidad Anáhuac as well as doctor in Education (Educational Evaluation) from the Universidad Complutense in Madrid. He is the principal investigator of the stable Research Group on ‘Education in Leadership’ at the UFV. He is a professor in the degree in Early Childhood Education and in the master’s degree in Educational Centre Management at the UFV. He collaborates with the Joint Diploma LSTV of the Open Reason Institute and the Pontifical Universities of Rome. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2118-9386; https://scholar.google.com.mx/citations?hl=es&pli=1&user=iKfSdpoAAAAJ

References

- Althof, W., and M. W. Berkowitz. 2006. “Moral Education and Character Education: Their Relationship and Roles in Citizenship Education.” Journal of Moral Education 35 (4): 495–518. doi:10.1080/03057240601012204.

- Arthur, J., K. Kristjánsson, D. I. Walker, W. Sanderse, and C. Jones. 2015. “Character Education in UK Schools.” University of Birmingham Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues. http://epapers.bham.ac.uk/1969/1/Character_Education_in_UK_Schools.pdf

- Bastons, M. 2020. “The Role of Desire in Action.” In Desire and Human Flourishing, edited by M. Bosch, 17–27. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-47001-2_2.

- Berkowitz, M. W. 2002. “The Science of Character Education.” Bringing in a New Era in Character Education 508: 43–63.

- Berkowitz, M. W., and A. Bustamante. 2013. “Using Research to Set Priorities for Character Education in Schools: A Global Perspective.” KEDI Journal of Educational Policy 10 (3): 7–20.

- Bernal, A., C. Naval, C. Sobrino, A. D. Varela, and Dabdoub J. P. 2017. “An exploratory Delphi study on Character Education in Latin-American countries: Argentina, Colombia and Mexico.” In La educación ante los retos de la ciudadanía, 172–184. Murcia, España: XIV Congreso Internacional de Teoría de la Educación.

- Bosch, M. 2020. “Education of Desire for Flourishing.” In Desire and Human Flourishing, edited by M. Bosch, 29–44. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-47001-2_3.

- Burgos, J. M. 2013. Antropología: Una guía para la existencia. Madrid: Palabra.

- Conde-Flores, S., B. García-Cabrero, and A. M. Alba-Meraz. 2017. “Civic and Ethical Education in Mexico .” In Civics and Citizenship. Moral Development and Citizenship Education, edited by B. García-Cabrero, A. Sandoval-Hernández, E. Treviño-Villareal, S. D. Ferráns, and M. G. P. Martínez, 39–66. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Consejo de Europa. 2018. “Competencias para una cultura democrática. Convivir en pie de igualdad en sociedades democráticas culturalmente diversas.” https://rm.coe.int/libro-competencias-ciudadanas-consejo-europeo-16-02-18/168078baed

- De Finance, J. 1966. Ensayo sobre el obrar humano. Madrid: Gredos.

- EU Communities. 2006. “Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18December 2006 on Key Competencies for Lifelong Learning (2006/962/EC).” European Communities. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2006:394:0010:0018:EN:PDF

- EU Communities. 2007. Key Competencies for Lifelong Learning. European Reference Framework. Brussels: European Communities. http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/education_culture/publ/pdf/ll-learning/keycomp_en.pdf

- Fuentes, J. L. 2018. “Educación del carácter en España: Causas y evidencias de un débil desarrollo.” Estudios sobre educación 35: 353–371. doi:10.15581/004.34.353-371.

- Gomes-Dias, A., and M. J. Hortas. 2020. “Educación para la ciudadanía en Portugal.” Revista Espaço do Currículo 13 (2): 7–14.

- Guardini, R. 1999. Ética. Lecciones en la Universidad de Munich. Madrid: BAC.

- Kirchgasler, C. 2018. “True Grit? Making a Scientific Object and Pedagogical Tool.” American Educational Research Journal 55 (4): 693–720. doi:10.3102/0002831217752244.

- Kohlberg, L., and R. Mayer. 1972. “Development as the Aim of Education.” Harvard Educational Review 42 (4): 449–496. doi:10.17763/haer.42.4.kj6q8743r3j00j60.

- Kolb, D. A. 2015. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education.

- Lickona, T. 1991. Educating for Character. New York: Bantam.

- Lickona, T. 1996. “Teaching Respect and Responsibility.” Reclaiming Children and Youth: Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Problems 5 (3): 143–151.

- Linde, A. 2010. “Síntesis y valoración de la teoría sobre el desarrollo moral de Lawrence Kohlberg.” Ágora Papeles de Filosofía 29 (2): 31–54. http://hdl.handle.net/10347/7373

- Lopes, J., C. Oliveira, L. Reed, and R. A. Gable. 2013. “Character Education in Portugal.” Childhood Education 89 (5): 286–289. doi:10.1080/00094056.2013.830880.

- López, J., and S. Ortiz de Montellano. 2021. “Educación en liderazgo para estudiantes universitarios: propuesta de un meta-modelo.” In Metodologías activas con TIC en la educación del siglo XXI, edited by O. Buzón García and C. Romero García. Madrid: Dykinson.

- Marshall, L., K. Rooney, A. Dunatchik, and N. Smith. 2017. “Developing Character Skills in Schools. Quantitative Survey.” NatCen Social Research. Department of Education, UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/developing-character-skills-in-schools

- Marulanda, J. C. 2012. “El emotivismo y su influencia en las teorías contemporáneas del desarrollo moral.” Polisemia 8 (13): 76–85.

- Melina, L., J. Noriega, and J. J. Pérez-Soba. 2007. “Caminar a la luz del amor. Los fundamentos de la moral cristiana.” Madrid, Palabra.

- Nucci, L. P., D. Narvaez, and T. Krettenauer, Eds. 2014. Handbook of Moral and Character Education. New York: Routledge.

- Ortega y Gasset, J. 2004. Introducción a una estimativa. ¿Qué son los valores? Madrid: Encuentro.

- Park, N., C. Peterson, and M. E. Seligman. 2006. “Character Strengths in Fifty-Four Nations and the Fifty US States.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 1 (3): 118–129. doi:10.1080/17439760600619567.

- Pattaro, C. 2016. “Character Education: Themes and Researches. An Academic Literature Review.” Italian Journal of Sociology of Education 8 (1): 6–30. doi:10.14658/pupj-ijse-2016-1-2.

- Peterson, A. 2020. “Character Education, the Individual and the Political.” Journal of Moral Education 49 (2): 143–157. doi:10.1080/03057240.2019.1653270.

- Revell, L., and J. Arthur. 2007. “Character Education in Schools and the Education of Teachers.” Journal of Moral Education 36 (1): 79–92. doi:10.1080/03057240701194738.

- Spaemann, R. 1987. Ética: Cuestiones fundamentales. Pamplona: Eunsa.

- Spaemann, R. 2003. “Acerca de la dimensión ética del actuar.” Madrid: Eiunsa.

- Taylor, M. 1994. “Overview of Values Education in 26 European Countries.” In Values Education in Europe: A Comparative Overview of A Survey of 26 Countries in 1993, edited by M. Taylor, 1e66. Dundee: Scottish Consultative Council on the Curriculum.

- Thornberg, R., and E. Oğuz. 2016. “Moral and Citizenship Educational Goals in Values Education: A cross-cultural Study of Swedish and Turkish Student Teachers’ Preferences.” Teaching and Teacher Education 55: 110–121. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.01.002.

- Treviño, E., C. Béjares, C. Villalobos, and E. Naranjo. 2017. “Influence of Teachers and Schools on Students’ Civic Outcomes in Latin America.” The Journal of Educational Research 110 (6): 604–618. doi:10.1080/00220671.2016.1164114.

- Velásquez, A. M., R. Jaramillo, J. A. Mesa, and S. D. Ferráns. 2017. “Citizenship Education in Colombia: Towards the Promotion of a Peace Culture .” In Civics and Citizenship. Moral Development and Citizenship Education, edited by B. García-Cabrero, A. Sandoval-Hernández, E. Treviño-Villareal, S. D. Ferráns, and M. G. P. Martínez, 67–83. Rotterdam: SensePublishers. doi:10.1007/978-94-6351-068-4_3.

Appendix A.

Questionnaire

School Principal or Teacher

Gender: male or female

How long have you been teaching

Name of school

Country

Type of school: private, charter, public

Does the school have Christian principles: yes/no

What do you understand by virtue education?

Do you think that education in virtues is the same as education in values? Justify your answer

Tell us if the school has a virtue education programme or something similar.

What are the six main virtues you seek to educate in your elementary school students?

What are the six main virtues you seek to educate in your high school students?

Among the virtues you promote, are there any that have been included on request of the governmental educational authorities?

What civic virtues do you promote the most at school?

Mention four educational practices or strategies used in the school to educate in virtues.

Who are the most important agents in the virtue education of students in the school

Does the school promote the formation of virtues among peers, i.e. among students?

Is it important in your school to have teachers trained in this area?