ABSTRACT

Through a discourse analysis of French and Swedish legislative debates from 1968 to 2017, this article examines how actors challenge and reinforce dominant ideas about the link between nationality and political rights. We argue that the broader political culture influences which discursive strategies – or ‘frames’ – are more likely to structure parliamentary debates in different national contexts. However, our analysis also shows that legislators sometimes develop new discursive frames in which they reinterpret dominant norms to make them consistent with their views. Through this incremental process of reinterpretation and reformulation of dominant ideas, debates over non-citizen voting rights have chipped away at the link between nationality and political rights. Our findings suggest that initiatives to enfranchise non-citizens trigger lower levels of conflict when they can be framed as a policy tool for immigrant integration rather than as a matter of popular sovereignty.

Nationality determines access to political rights in most contemporary democracies. Yet, over forty countries currently allow non-citizens to vote at various levels, and legislative proposals to implement similar reforms have been discussed in many other places (Arrighi and Bauböck Citation2017, 624). Some of these initiatives have triggered intense political conflicts, while others have generated little controversy, either because they have met widespread resistance or because they have been received with almost unanimous agreement. Why is the political inclusion of non-citizens a salient and polarizing issue in some contexts but not others?

Empirical research on non-citizen voting rights has primarily focused on explaining institutional change, that is, why some states allow foreigners to participate in local, regional, or national elections (Earnest Citation2008, Citation2014, Citation2015; Toral Citation2015; Justwan Citation2015; Arrighi and Rainer Citation2017). This article focuses instead on processes of normative change. Through a discourse analysis of French and Swedish legislative debates from 1968 to 2017, it examines how actors challenge and reinforce dominant ideas about the link between nationality and political rights.

The article makes three contributions to research on non-citizen enfranchisement. First, we document the discursive strategies that legislators use to express their support or opposition to the political inclusion of non-citizens, and how these strategies differ depending on the sex of legislators, party ideology, and the broader political culture of the country.

Second, drawing on ‘framing’ theories from research on social movements (e.g. McAdam et al. Citation1996; Koopmans and Statham Citation1999a; Benford and Snow Citation2000), we argue that the broader political culture influences which of these frames are more likely to structure parliamentary debates in different national contexts. However, precisely because legislators operate within the constraints of these ‘discursive opportunity structures,’ they sometimes develop new discursive frames in which they reinterpret dominant norms to make them consistent with their views. Through this incremental process of reinterpretation and reformulation of dominant ideas, debates over the enfranchisement of non-citizens have chipped away at the link between nationality and political rights.

Third, democratic theorists and activists most often ground their arguments for non-citizen enfranchisement on a normative principle of ‘all-affected interests’, arguing that everyone affected by collective decisions should have a say in those decisions and not only those who are formal members of a predefined ‘people’ (Beckman Citation2006; Song Citation2009; Owen Citation2012). The normative case for this view is indeed very compelling. Unfortunately, our analysis suggests that it is an ineffective discursive strategy to promote non-citizen voting rights. When supporters predominantly relied on this type of arguments, debates in parliament became structured as an intractable moral conflict between competing notions of popular sovereignty, and those proposals failed to rally sufficient support across party lines. This was the case in both France and Sweden. Conversely, proposals to enfranchise non-citizens were more likely to build broad coalitions when the issue could be framed either as a strategy for immigrant integration (e.g. local voting rights in Sweden) or in terms of recognizing the formal status of non-citizens as members of a sovereign people (e.g. local voting rights for EU citizens in France).

These findings echo previous research on successful campaigns to enfranchise non-citizen residents in other European countries (Jacobs Citation1998, Citation1999; Pedroza Citation2013), as well as other studies about the impact of earlier suffrage movements on norms of political inclusion (McCammon et al. Citation2001; McCammon Citation2012; McConnaughy Citation2013). They provide a sobering yet hopeful lesson for more general discussions on the suffrage (regarding, for example, the enfranchisement of other groups, such as individuals with mental disabilities, felons, and minors), as well as debates about other forms of immigrant inclusion (such as those related to social rights and welfare entitlements).Footnote1 Movements for political inclusion are most effective not when they directly reject prevalent exclusionary norms, but when they are able to reinterpret those norms in creative and strategic ways to justify the broadening of the dêmos.

Empirical research on the enfranchisement of non-citizens

Despite the strong tie that still exists between nationality and political rights, several democracies today allow non-citizen residents to vote at some level, while other countries impose restrictions on the vote of non-resident citizens (Lappin Citation2016). In most cases, non-citizen voting rights are limited to local elections, although a small number of countries allow non-citizens to also vote in national elections (Earnest Citation2008, 33; Arrighi and Rainer Citation2017, 624). Similarly, some democracies have extended the same voting rights to all non-citizens that reside in the country, while others limit those rights to non-citizens from specific countries as part of processes of economic integration or due to shared colonial histories, perceived cultural affinities, or reciprocity agreements (Earnest Citation2008, 32).

A growing literature has advanced our understanding of cross-national variation in non-citizen voting rights. New data collection projects are documenting how contemporary democracies vary in the extent, level, and restrictions around non-citizen suffrage (Schmid, Piccoli, and Arrighi Citation2019). This has inspired numerous quantitative studies that analyze the effects of different models of citizenship, judicial institutions, welfare state generosity, partisanship, interpersonal trust, and the diffusion of international norms, on the likelihood that a country will grant more comprehensive voting rights to non-citizens (Earnest Citation2008, Citation2014, Citation2015; Toral Citation2015; Justwan Citation2015; Arrighi and Rainer Citation2017). Similarly, several case studies have produced rich descriptions of initiatives for suffrage expansions (Hammar Citation1977; Jacobs Citation1998; Andres Citation2013; Hayduk Citation2012; Teney and Jacobs Citation2016), while other comparative studies have treated this question as part of broader trends in integration policies (Soysal Citation1994; Joppke Citation1998; Koopmans et al. Citation2005).

These studies show that the political inclusion of non-citizens is shaped by processes that are orthogonal to other aspects of the politics of migration. Although courts tend to have a more liberal orientation than legislatures in matters of immigration (Joppke Citation1998), courts have repealed reforms related to non-citizen voting rights in the US, Germany, Austria, Italy, and Greece after sub-national legislative bodies had already approved them (Neuman Citation1991; Hayduk Citation2012; Triandafyllidou Citation2014). Even though left-wing parties are generally advocates of extending the franchise to non-citizens and right-wing parties tend to be opposed to such initiatives, local voting rights passed with support across party lines in places like Sweden and the Netherlands (Hammar Citation1977; Jacobs Citation1998). Finally, efforts to enfranchise non-citizens have faced strong opposition in civic-republican states (e.g. France, the United States), as well as in countries characterized by ethno-cultural conceptions of national identity (e.g. Germany, Austria). At the same time, non-citizen voting rights have been adopted by countries with civic (e.g. Netherlands, Sweden) and ethnic (e.g. Denmark, Norway) models of nationhood (Koopmans and Michalowski Citation2017).

Most of this empirical research has focused on explaining institutional change – i.e. why non-citizen residents are enfranchised in some cases but not others. Less attention has been paid to the question of normative change. How do political actors challenge and reinforce prevalent norms about the link between nationality and political rights? How do these norms vary across liberal democracies and over time? Why are reforms towards the political inclusion of foreigners strongly opposed in some contexts but enthusiastically accepted at other times?

This article builds on the seminal work by Dirk Jacobs and Luicy Pedroza on the parliamentary debates that led to the local enfranchisement of non-citizen residents in the Netherlands (Jacobs Citation1998), Belgium (Jacobs Citation1999), and Portugal (Pedroza Citation2013).Footnote2 However, it also complements those studies in two ways. First, this article focuses on the implications of discursive conflict for normative change rather than as an explanation for the success or failure of legislative initiatives. Second, this article adopts a comparative perspective in order to observe how debates over nationality and political rights are shaped by the broader political culture in different national contexts.

Contestation over the definition of popular sovereignty

An effective way of examining how norms vary across contexts and over time is to look at the discursive frames that actors use to justify their position on contentious issues. By ‘discursive frames’ or ‘framing’, we mean the ‘conscious strategic efforts by groups of people to fashion shared understandings of the world and of themselves that legitimate and motivate collective action’ (McAdam et al. Citation1996, 6).Footnote3 From this perspective, frames generally make a reference to ideas that are prominent in the broader political culture and that influence which claims are more likely to be perceived as sensible, realistic or legitimate (Koopmans and Statham Citation1999b, 228). In other words, discursive frames reflect the overarching ‘discursive opportunity structures’ that influence which claims gain visibility in the public sphere, resonate positively or negatively with the claims of other actors, and achieve legitimacy in public discourse (Koopmans et al. Citation2005, 19).

At the same time, discursive frames also show how actors work within those discursive opportunity structures to transform dominant ideas by reinterpreting and reformulating them in creative and strategic ways. Previous movements for political inclusion provide some of the most successful examples of this process of normative change through discursive contestation. For instance, research on the women’s suffrage movement in the United States has found that, prior to the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, suffragists fared better in states where activists framed the political inclusion of women as a matter of ‘expediency’ rather than ‘justice’ (McCammon Citation2001; McCammon et al. Citation2001).Footnote4 Whereas ‘justice’ arguments held that women were citizens just as men and thus were entitled to equal suffrage, ‘expediency’ arguments claimed that women should be granted the vote because they would bring ‘womanly’ skills to politics and would use their nurturing abilities to solve societal problems that concerned families and children (McCammon Citation2001, 460–61). Activists strategically used these expediency arguments to frame women’s political inclusion in a way that resonated with dominant patriarchal norms about the gendered separation of the private and public spheres. This made it easier for suffragists to win supporters, to obtain more extensive political rights, and to undermine prevalent norms about political exclusion on the basis of gender (McCammon et al. Citation2001, 66).

Based on this discussion, what are the norms that actors are likely to evoke when they take part in discursive conflicts over the enfranchisement of non-citizens? Democratic theory offers some guidance in this regard.

At the most general level, democracy is a form of governance based on the ideal of popular sovereignty, which establishes that ‘“the people” (considered collectively) [should govern] itself through the entitlement of “the people” (considered severally) to participate as political equals in the decision-making process’ (Owen Citation2012, 129). However, as democratic theorists have shown, we can identify at least two different interpretations of this ideal.

On the one hand, ‘bounded’ conceptions of popular sovereignty became dominant with the consolidation of the Westphalian international system, the rise of national-states, and the diffusion of ideas of national self-determination that established the collective right of a people to rule itself. From this perspective, popular sovereignty is understood as the collective right of a political association to govern itself through the inclusion of all its members (and only its members) in the making of collectively-binding decisions (Bohman Citation2007, 28). Consequently, this view makes a two-pronged claim about the boundaries of the people. Externally, the people must be clearly demarcated from non-members since their political participation would represent an encroachment on the collective right to self-government. Internally, all the members of the people must have an equal right to participate in the collective decisions that govern them; otherwise, the people’s right to self-government would be captured by a subset of its members. Based on this bounded view of popular sovereignty, access to political rights is determined by a principle of membership (Beckman Citation2006). Individuals are entitled to political rights because they are members of the people, regardless of whether membership is defined by ethno-cultural factors, social ties, or adherence to political values. Indeed, bounded conceptions of popular sovereignty can be consistent with civic-republican ideals of nationhood as long as formal membership through naturalization is deemed necessary for gaining access to political rights (Smith Citation2008; Song Citation2009, 613).

On the other hand, ‘open’ conceptions of popular sovereignty start from an ideal of personal autonomy that establishes individuals’ right to rule themselves (Soysal Citation1994; Benhabib Citation2004; Arrighi and Rainer Citation2017; Abizadeh Citation2008; Song Citation2009; Pettit Citation2012). From this perspective, ‘the people’ can only be identified after we know who is affected by, subject to, or has a stake in collectively-binding decisions. Popular sovereignty is thus not a collective right but an empirical property of political systems in which individuals are effectively empowered to participate in the making of the laws that bind them. This means that popular sovereignty is not tied to a discrete dêmos. Instead, it can be the result of multiple, porous and overlapping dêmoi in which individuals are able to influence the collective decisions that infringe on their personal autonomy (Bohman Citation2007, 30–31; Song Citation2009, 610–11; Näsström Citation2011, 123–24) . As a result, access to political rights is to be determined by an all-affected principle, not by formal membership in a pre-defined community (Beckman Citation2006; Owen Citation2012). These ideas have gained popularity with cosmopolitan theories of democracy (Held Citation1995; Archibugi, Held, and Köhler Citation1998; Goodin Citation2016), but elements of this tradition were already present in pre-modern democratic theory, neo-roman theories of liberty, and Kantian cosmopolitanism (Skinner Citation1998).

Both of these notions of popular sovereignty are built into the shared ideological background of contemporary democracies. Nevertheless, historical legacies are likely to shape the political culture of a country in ways that foreground one view of popular sovereignty over the other. For instance, countries that first established democratic institutions after a war of independence or a social revolution often cultivate national myths that celebrate the people’s assertion of its collective right to self-government against foreign domination or domestic tyranny. Conversely, countries with traditions of popular participation through political assemblies of various kinds (e.g. local councils, peasant assemblies, craftsmen guilds) are presumably more likely to be open to the differentiated distribution of political rights across multiple spheres of collective decision-making. Along these lines, countries with colonial histories may be more likely to emphasize boundaries between ‘the people’ and other subjects of the state, or, alternatively, they may be more likely to embrace post-national conceptions of peoplehood. Therefore, even among Western liberal democracies, discursive conflicts over non-citizen enfranchisement are likely to revolve around different frames, to generate different levels of contestation, and to impact broader democratic norms in different ways.

Research design

In what follows, I present the results of a discourse analysis of French and Swedish legislative debates on non-citizen voting rights from 1968 to 2017. Following the tradition of framing theory in social movements research (Snow and Benford Citation1988; Benford and Snow Citation2000; McAdam et al. Citation1996; Koopmans and Statham Citation1999b), the goal is to (1) identify which discursive frames different actors mobilize; (2) how those frames have changed over time; and (3) how these frames relate to the intensity of political conflict around specific initiatives in different contexts.

Between 1968 and 2017, several legislative proposals were discussed in both countries in the context of growing immigration flows and European integration. The number of non-citizen residents as a share of the population reached similar levels in both places during this period (roughly around 6%), so the potential electoral impact of their inclusion was more or less comparable (Eurostat Citation2017). Moreover, both France and Sweden have in place liberal citizenship policies with low requirements for naturalization. Focusing on countries with relatively open citizenship regimes allows us to observe how actors challenge the link between nationality and political rights even in places where it is relatively easy to become a member of the nation.

At the same time, these two countries have followed very different paths towards democracy and have developed distinct national political cultures, which gives us the opportunity to observe how legislators resort to different discursive frames to legitimate their positions in relation to those larger normative scaffoldings. On the one hand, the legacies of the French Revolution have fostered national myths that give great prominence to ideas about the ‘people’ as an indivisible collective agent (Lefebvre Citation2003; Rosanvallon Citation2007, 19–21). Yet, the universalistic ideals of French republicanism have coexisted with (and often contributed to) a violent history of colonialism that disenfranchised colonial subjects on the basis of class, race and religion (Conklin Citation1997; Wilder Citation2005; Bateman Citation2018). These legacies continue to shape debates about citizenship in the country and are likely to influence the way actors frame discussions about the relationship between nationality and political rights. On the other hand, Sweden’s path to democracy evolved from a long tradition of popular participation through multiple spheres of functional and territorial representation and does not share with France a similar colonial past (Knudsen and Rothstein Citation1994, 212; Sørensen and Stråth Citation1997, 260). By comparing legislative debates in these two countries we can then observe how different political cultures shape the structure of discursive conflicts around the political inclusion of foreigners in contemporary Western democracies.

The data consists of statements hand-coded by the author, with the help of a research assistant, for every debate in the Swedish Riksdag and in the French Senate and National Assembly devoted to proposals to enfranchise non-citizen residents, as well as related statements made in debates on other topics that could be identified through keyword searches.Footnote5 In order to be included in the dataset, a statement had to be voiced during a formal legislative session and provide a concrete reason in favor or against non-citizen voting rights for sub-national or national elections. We identified 552 arguments in France and 149 in Sweden. The majority of those statements were voiced during discussions on specific proposals, generally over one or two sessions. We did find, however, a small number of isolated arguments made during legislative debates on other issues.

For each argument, we coded: (1) the position (for or against); (2) whether it discriminated between non-citizens depending on their country of origin; (3) whether it referred to voting rights for local or national elections; (3) the frame and (4) sub-frame that the speaker used to justify their position; and (5) the name, (6) party, and (7) sex of the speaker. The frames and sub-frames were generated deductively based on the normative literature on non-citizen voting rights (Renshon Citation2009; Hayduk Citation2012). To ensure that the categories were mutually exclusive and exhaustive across national contexts, actors, and initiatives, a pilot analysis was carried out on media articles and grey literature on the topic in France, Sweden, and the United States.Footnote6

We coded arguments for and against non-citizen voting rights according to eight possible frames (also see ):Footnote7

Facilitating integration (in favor): arguments that advocated for non-citizen voting rights as a policy tool to facilitate the integration of immigrants by lowering ethnic tensions, encouraging naturalization, building a sense of community, or teaching democratic habits.

Fairness (in favor): arguments that drew on open conceptions of popular sovereignty to advocate for non-citizen voting rights. These arguments voiced concerns about the ways in which non-citizen residents are affected by political decisions, about their subjection to the laws of the host country, or about their stakes in communities to which they contribute through their labor, taxes, military service, and involvement in associational life.

Democracy (in favor): arguments that drew on bounded conceptions of popular sovereignty to advocate for non-citizen voting rights. These arguments generally took one of two possible forms. They either claimed (a) that non-citizen residents are already de facto members of the nation and thus entitled to political rights; or (b) that the exclusion of non-citizens creates political inequalities among citizens in the form of asymmetries in the allocation of public resources or lower responsiveness by public officials. Note that both types of arguments advance claims about the political rights of members of the nation, not about affectedness.

Other (in favor): context-specific arguments, such as those celebrating the importance of local collective identities or advocating the need to weaken anti-immigrant parties.

Cultural integrity (against): arguments against non-citizen voting rights based on the protection of cultural values and national identity.

National interest (against): arguments against non-citizen voting rights based on concerns about the national interest, such as diplomatic tensions with other states or threats to national security.

Bounded demos (against): arguments that drew on bounded conceptions of popular sovereignty to oppose the enfranchisement of foreigners. These arguments generally expressed fears about lessening the value of legal citizenship or of creating second-class citizens through the allocation of differentiated political rights for local and national elections.

Other (against): context-specific arguments such as worries about the likelihood of electoral fraud or the logistical challenges of maintaining different voting registers for local and national elections.

Table 1. Frames for arguments.

Assessing the intensity of contestation in France and Sweden (1968-2017)

In France, initiatives to enfranchise non-citizens gained notoriety in 1981 when François Mitterrand included the issue as part of his campaign platform. Since then, it has been a highly contentious issue in French politics. In 1992, the Maastricht Treaty required EU member states to allow European nationals to vote in local and European elections (Lappin Citation2016, 867–68). Those reforms were discussed by both chambers in 1992 and finally approved in 1997. Three proposals to grant local voting rights to non-EU citizens were introduced to the National Assembly during the 2000s: one in 2000, which passed but was never turned to the Senate for discussion; and two more in 2002 and 2010, both of which were voted down. One proposal was introduced to the Senate in 2011, which passed but was not turned to the National Assembly. Shorter debates on the topic also occurred around other bills, such as the discussions prior to the RESEDA law of 1998, the constitutional reforms for the modernization of the Fifth Republic of 2008, and the anti-terrorist laws of 2016, none of which passed.

In Sweden, the enfranchisement of non-citizens was first brought up in Parliament in 1968 (Hammar Citation1977, 9). A bill that proposed non-citizen voting rights for local elections was introduced in 1974 and approved with unanimous support a year later in the context of major constitutional reforms and an overhaul of the country’s immigration policies (Riksdagsförvaltningen Citation1975). Debates on the enfranchisement of non-citizens for national elections peaked between 1977 and 1979. The issue continued to be part of the agenda of the Social Democrats (S) in the subsequent years, but none of those initiatives gained enough support from center and center-right parties to pass. After the mid-1980s, non-citizen voting rights were only discussed as part of debates on other matters, usually related to electoral reforms or revisions to the naturalization law. The topic was again briefly brought up in the 2010s, when the Sweden Democrats (SD), a far-right anti-immigrant party, entered Parliament and called for the withdrawal of local voting rights from non-citizens.

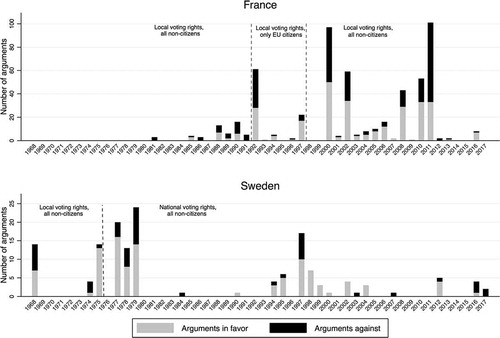

presents the number of arguments related to non-citizen voting rights per year for each country. The vertical dotted lines demarcate debates around different initiatives depending on whether they proposed to enfranchise non-citizens at the local or national level and whether they included nationality restrictions or not. presents the number of arguments in favor and against non-citizen voting rights by party family, country and type of initiative. Together, these two figures offer a general picture of the intensity of political conflict around each proposal.

We can get a sense of the saliency and divisiveness of these debates by looking at (1) the total number of arguments voiced around specific proposalsFootnote8, (2) the number of arguments voiced in favor and against the initiative as a share of the total number of arguments; (3) the position adopted by the different political parties; and (4) changes over time in (1) and (2).

and jointly show that the intensity of political conflict varied significantly across different initiatives in each country. Highly visible debates were also strongly polarized, with a cleavage drawn through the middle of the political spectrum and parties closing ranks on each side. This was the case for the proposals to extend local voting rights to non-EU citizens in France and to grant national voting rights to non-citizens in Sweden. Conversely, debates that culminated with the local enfranchisement of EU-citizens in France and local voting rights in Sweden were characterized by less visible debates (lower number of arguments relative to other initiatives in the country), widespread support across the political spectrum, and a decline over time in opposition to those initiatives. Finally, as shown in , arguments for the enfranchisement of non-citizens at the national level were very rare in France, while we identified no arguments that singled out certain non-citizens to be enfranchised (or refused voting rights) on the basis of their nationality in Sweden.

Table 2. Number of arguments by type of initiative.

Discursive frames and political contestation

Turning to the analysis of the discursive frames, presents the frequency with which each frame was used by female and male legislators in each country. In Sweden, the vast majority of arguments in favor of non-citizen voting rights referred to concerns about ‘fairness’, that is, they framed non-citizen enfranchisement as a matter of extending political rights to those affected by political decisions. In France, arguments about ‘facilitating integration’ and ‘democracy’ were voiced by supporters as frequently as frames related to ‘fairness’. In both countries, the majority of arguments against non-citizen voting rights evoked bounded notions of popular sovereignty.

Table 3. Distribution of frames by country and sex of speaker.

Roughly 20% of the statements related to non-citizen voting rights were voiced by women in both countries. In most cases, female legislators expressed support for these initiatives. This is likely because left-wing and green parties, which were the main advocates of non-citizen suffrage, also tended to include more women as legislative candidates, especially earlier in the period (Caul Citation2001; Keith and Verge Citation2018; Santana and Aguilar Citation2018). Having said that, in the Swedish case women MPs from a centrist party (Folkpartiet) have played a very active role in these debates (see Table B5 in the supplementary appendix for disaggregated data on the number of arguments voiced by women by party family). We do not observe significant differences between men and women in the frames they used to oppose non-citizen voting rights. However, women resorted to arguments about fairness to advocate for the inclusion of non-citizens more often than men, who were more likely (at least in the French case) to resort to other types of frames.

shows the frequency of these frames across specific initiatives. Here we already observe some important patterns. In both countries, the highly contentious debates were structured as a conflict between competing views of popular sovereignty. This was most clearly the case in the discussions around national voting rights in Sweden. In France, advocates of the local enfranchisement of non-EU citizens unsuccessfully tried to frame the issue in different ways to move it away from discussions over popular sovereignty. However, those who opposed these initiatives refused to discuss them as anything other than a threat to the sovereignty of the French people. Let us look at each of these cases in more detail.

France

Local voting rights for EU-citizens

In France, debates about the enfranchisement of EU citizens generated relatively low levels of contestation. The only parties that consistently opposed this initiative were the Rally for the Republic (RPR) and the National Front (FN), while the position of the center-right Union for French Democracy (UDF) shifted over time. By 1997 when the reforms were passed, the majority of UDF deputies, along with the Socialist Party (PS), the Communist Party (PCF), the Green Party, and other smaller leftist forces expressed their support for the local enfranchisement of EU citizens.

At the beginning of the debates in 1992, the majority of arguments against this initiative was based on a bounded conception of popular sovereignty. For example, Gérard Larcher, senator for the RPR, argued:

“My dear colleagues, to be opposed to the enfranchisement of non-French members of the European Community is not, I believe, to be closed in on oneself. On the contrary, it means the affirmation of the two principles upon which the Republic is built: first, the Republic, that is, the nation, is one and indivisible; second, citizenship belongs to those who, together, represent the constitutive elements of the nation” (Senate Debate, 10 October 1992).

As the debates progressed, these arguments became less frequent. Those who continued to oppose this reform increasingly referred to other concerns, such as the worry that enfranchising European citizens would open the door for the enfranchisement of other non-citizens (‘other’).

The most distinctive aspect of these debates was that the enfranchisement of EU-citizens was very early on framed as a matter of recognizing the collective right of self-determination of a European dêmos (‘democracy’). In the words of, Bernard Bosson, deputy for the UDF, asserted:

“At a time when the Treaty of Maastricht essentially represents the creation of a single currency, it is important […] to underline our will to build not only a Europe of money and the economy. Our twelve governments must foster the adherence of all Europeans to a shared community of fate, behind the symbols of the European flag, anthem and passport […] The recognition of such a European citizenship entails granting the right to vote and to run for office in municipal and European elections to the citizens of the twelve member-states, only to them and under very strict conditions” (National Assembly Debate, 6 May 1992).

This frame was typically used by center-left and center-right parties to support the initiative, but every political force, except for the FN, expressed at least once an argument along these lines (see Table B1 in the appendix). Very few legislators, primarily from the PCF, framed their views in terms of affectedness. For example, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, senator for the PCF, explicitly defended an open conception of popular sovereignty:

“The nation is the place of citizenship; it is neither ethnic, nor religious or linguistic. Citizenship is based on the collective exercise of power. Wherever there is power, citizenship must be exercised. […] If the power to be the masters of our lives, in their full social and economic reality, is located at the European level, being a real democrat means pushing for the development of the European nation and, with it, the European citizenship” (Senate Debate, 9 June 1992).

By the end of the debates in 1997, a narrative rooted in a bounded conception of popular sovereignty, in which access to political rights was determined by membership in a European ‘People’, became the most common justification for the local enfranchisement of EU citizens. In other words, proponents of this initiative were able to frame it in a way that was compatible with dominant ideas about the allocation of political rights on the basis of formal membership. This contributed to lower opposition to the reform. Center-right parties, such as the UDF, that supported European integration but that opposed the inclusion of third-country nationals could use this frame to defend the selective enfranchisement of some non-citizens but not others. As we will see below, the success of this initiative broadened political rights for some foreign residents, but it also cemented the weight of bounded conceptions of popular sovereignty in French political debates.

Local voting rights for all non-citizens

Initiatives to grant local voting rights for non-EU citizens have repeatedly triggered intense conflicts in French politics. The structure of those debates has changed very little from the first discussions in the 1980s to the height of the debates in the 2000s. We observe very few changes in the positions adopted by political parties and in the discursive frames they use to support them.

Contrary to the discussions around local voting rights for EU citizens in which ‘democracy’ frames were dominant, arguments for the enfranchisement of non-EU citizens relied as frequently on frames about ‘integration’ and ‘fairness.’ There were, however, important differences among the parties that supported these initiatives.

The PS unsuccessfully tried to pursue a similar discursive strategy as in the case of EU citizens by reframing the enfranchisement of third-country nationals as a matter of recognizing their social (if not formal) membership in French society (around 26% of their arguments). Noticing that these arguments were not resonating with other actors, the PS then shifted its discursive strategy to focus on instrumental arguments about the role of voting rights in fostering integration (43% of their arguments).

Conversely, the PCF and to a lesser extent the Greens primarily relied on arguments about fairness to express their support for these initiatives (see Table B2 in the appendix). For example, Noel Mamère, deputy for the Green Party, argued in 2000:

“The vast majority of non-EU foreign residents that live in France have been here for several years, meeting all their duties. But they don’t have any rights over the decisions that affect their everyday lives. They work and pay their taxes, raise their children, participate in schools and universities, teach, take part in the administrative councils of the social security boards, are delegates of trade unions and militants in associations, but, without voting, they live in a true political apartheid” (National Assembly Debate, 2 May 2000).

On the other side of the debate, center-right political parties – UDF and later the Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) – consistently voiced the need to protect the boundaries of the people: 69% of their arguments against the enfranchisement of non-EU citizens were framed as a defense of a bounded conception of popular sovereignty. Such arguments insisted that enfranchising foreign residents only for local elections would create second-class citizens and divide the popular will in ways that were incompatible with republican values of legal equality and the priority of the common good. Interestingly, this was not a problem, according to them, in the case of EU citizens. By granting EU citizens local voting rights in their place of residence and national voting rights in their country of origin, European countries were enacting the right to collective self-government of the European people.

Similarly, center-right parties repeatedly argued that nationality should be the only principle for democratic inclusion. According to them, rather than creating second-class citizens with limited political rights, France offered non-citizens the possibility to become full citizens through liberal naturalization laws.

It is also worth pointing out the conspicuous paucity of references to France’s colonial past in these debates, especially given that the majority of third-country nationals that would be enfranchised by these initiatives were first- and second-generation immigrants from former colonies. Advocates rarely referred to shared ties of peoplehood derived from the history of colonialism to justify their position. In fact, explicit references to immigrants from former colonies were very rare, partly because leftist and green MPs tried to downplay criticisms that they promoted the enfranchisement of those groups because left-wing parties were more likely to benefit from their votes.

Sweden

Local voting rights for all non-citizens

In Sweden, few arguments were voiced against granting voting rights to all non-citizens at the local level, when the reform was discussed and passed between 1968 and 1975. The few concerns that were expressed were about technical concerns related to the implementation of different voting lists for national and local elections or voiced confusion about whether the proposal also included the enfranchisement of non-citizens at the national level. Resistance to this initiative disappeared once it became clear that the reform would focus exclusively on local elections. Since then, the only argument that we found that specifically opposed the enfranchisement of non-citizens at the local level was voiced in 2012 by the far-right SD.

The centrist Liberal Party – named Folkpartiet at the time – was the most vocal advocate of this proposal, initially presenting it as a matter of empowering those affected by collective decisions. For example, Ingrid Segerstedt Wiberg, member of the First Chamber, stated in 1968: ‘This need for individuals to feel at home means that they must also have the right to participate in social life at least in the municipality where they reside. There they deal with things that concern them intimately, affect their lives, their children, their work and their everyday existence’ (First Chamber Debate, 28 February 1968).

Social Democrats (center-left) were more likely to refer to voting rights as a policy instrument to facilitate immigrant integration (Table B3 in the supplementary appendix). By 1975, these ‘integration’ frames shaped the dominant narrative around the local enfranchisement of non-citizens, especially because the proposal became associated with a larger set of immigration reforms.

National voting rights for all non-citizens

After 1975, proposals to enfranchise non-citizens for parliamentary elections proved to be more contentious. Proponents of these initiatives, in particular the Social Democrats and the Left Party, tried again to frame the debate as a matter of integration policy. However, this time, the Liberal Party, which had been a vocal advocate for local voting rights in the 1970s, opposed those claims, arguing instead that naturalization was a more effective instrument for immigrant integration. By emphasizing naturalization as a requirement to obtain voting rights at the national level, the Liberal Party forced the debate towards polarizing discussions about the meaning of popular sovereignty. As a result, a cleavage was drawn at the center of the political spectrum.

On one side, the most common argument against extending national voting rights to non-citizens was a concern over weakening the meaning of membership in the nation (Table B4 in the supplementary appendix). In the words of Anders Björk, from the Conservative Party (Moderaterna): ‘If you have the right to vote in both parliamentary and municipal elections and also have the same social and other benefits as Swedish citizens, then citizenship will be a nullity in any practical sense’ (Riksdag Debate, May 11 1978). This was, by far, the most frequent argument used by opponents of the initiative, sometimes nuanced with the claim that non-citizens could naturalize to gain access to full political rights without diluting the meaning of formal citizenship (see Table B4 in the supplementary appendix).

On the other side of the debate, the Left Party, the Greens, and the Social Democrats, increasingly relied on arguments about affectedness to express their support for these initiatives. For example, Per Lager, from the Green Party, asserted in 2002: ‘We […] see no reason not to give people in Sweden the same voting rights as Swedish citizens. The determining criterion should be that the individual is publicly registered, not how long the person has lived in Sweden’ (Riksdag Debate, 4 April 2002). As a result, debates around these initiatives became a conflict between two competing notions of popular sovereignty.

Discussion and conclusion

What do these cases tell us about discursive conflict and normative change regarding the relationship between nationality and political rights? We highlight six important points.

First, in both countries the link between nationality and political rights is weaker than in the past, as the result of processes of economic integration and the diffusion of post-national norms of citizenship (Soysal Citation1994; Jacobson Citation1996). However, we cannot say the same thing about the strength of bounded conceptions of popular sovereignty. In both cases, membership still is the main principle to allocate political rights at the national level. In France, access to voting rights at the local and supra-national levels is also determined by formal membership, not to the French nation but to a European people.

Second, national political cultures affected which frames were more likely to structure parliamentary debates in each country. In France, legislators often referred to the ideological legacies of revolutionary republicanism to support their views. Supporters of non-citizen voting rights would frequently point towards the universalist spirit of the French Revolution and the recognition of voting rights for non-citizens in the Montagnard Constitution of 1793, while opponents referred to Jacobin ideals of a univocal and indivisible popular will. These arguments foregrounded issues of popular sovereignty and made it very difficult to frame the issue of non-citizen enfranchisement as merely a policy of immigrant integration.

In Sweden, on the other hand, local voting rights could be more easily framed as a tool for immigrant integration. Even those who initially opposed this reform and who later opposed the extension of national voting rights did not voice any concerns about popular sovereignty when it came to local suffrage. Indeed, we did not find any arguments that referred to a fragmentation of popular sovereignty as a result of the enfranchisement of different electorates at different levels. In sum, a less constraining discursive opportunity structure made it possible to frame local voting rights as a matter unrelated to popular sovereignty.

Third, within each country, center-left, left and green parties were more likely to be advocates of these initiatives. However, proposals to enfranchise non-citizen residents were only successful when they gained the support of centrist and center-right parties. For example, in late 2011, a left-wing majority in the French Senate passed an initiative to enfranchise all non-citizen residents at the local level. However, the newly elected President François Hollande did not push forward that proposal, despite majorities on both houses, worried about the consequences of a polarized debate (Rovan Citation2014).

Whereas MPs from green and left-wing parties were more likely to use frames about fairness that challenged bounded notions of popular sovereignty, MPs from center-left parties were more likely to resort to other discursive frames that circumvented conflicts over the definition of popular sovereignty, such as the role of voting rights in facilitating immigrant integration (see Tables B1 to B4 in the supplementary appendix). These differences in the way different parties tended to frame their position were consistent throughout the period, despite changes in the composition of the legislature (for example, between the early 2000s in France, when the center-right was in power, and 2012, when the Socialist Party controlled both houses and the Presidency).

Fourth, even though the broader political culture influenced which frames were more or less likely to gain traction in each country, we also observed instances in which legislators strategically reinterpreted those overarching norms to find new ways to justify their position. The discursive strategies that center and center-right parties used in France to justify the enfranchisement of EU-citizens but not third-country nationals offer a good example. By arguing that EU-citizens should be enfranchised at the local level because they were members of a European sovereign people, French legislators chipped away at the link between nationality and political rights while reinforcing bounded notions of popular sovereignty. This is very similar to the ways in which the women’s suffrage movement strategically reinterpreted patriarchal norms to argue for their political inclusion (McCammon et al. Citation2001; McCammon Citation2012).

Fifth, actors’ discursive strategies have unintended consequences in the long run. For example, in France, justifications for the enfranchisement of EU citizens actually strengthened bounded conceptions of popular sovereignty, further constraining the discursive opportunity structure for subsequent attempts to enfranchise third-country nationals. In Sweden, the discursive strategy that framed local voting rights as a tool for integration also hampered later efforts to enfranchise non-citizen residents at the national level. As these proposals were raised in the 1990s and 2000s, they were easily shut down by opponents who pointed instead to nationalization laws as a better alternative to foster immigrant integration (Jensen, Fernández, and Brochmann Citation2017).

Finally, the analysis suggests that arguments for political inclusion based on an all-affected principle do not seem to be very effective in building support for the enfranchisement of non-citizen residents. These arguments tend to structure debates around a moral or political conflict over the definition of popular sovereignty that makes it very difficult for parties to compromise. Of course, it is not possible to determine, based on our data, whether the success of particular initiatives was due to the discursive strategies of their supporters, or if it was precisely because those initiatives already commanded enough support that certain frames were more likely to be used. However, at a descriptive level, it is apparent that parties across the aisle rallied around proposals that could be framed in ways that were either compatible with the dominant conception of popular sovereignty (as in French debates over the enfranchisement of EU citizens) or as a matter of policy rather than politics (as in the case of local voting rights in Sweden). This is consistent with the findings of previous research on the debates that led to successful campaigns to enfranchise non-citizens in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Portugal (Jacobs Citation1998, Citation1999; Pedroza Citation2013).

In the past, suffrage movements were able to creatively and strategically reinterpret exclusionary norms to argue for their political inclusion. In doing so, they undermined the power of those exclusionary principles. As the campaign for non-citizen voting rights becomes one of the suffrage struggles of our time, it is worth remembering those lessons. Normative change is possible but it often follows a long and contentious road that is paved by compromise.

Supplementary_appendix.docx

Download MS Word (55.9 KB)Acknowledgments

The author thanks Antje Ellermann, Erik Bleich, Alan Jacobs, Ines Michalowski, Sarah Song, and the participants of the workshop “Race, Gender, and Class in the Politics of Migration: Empiricist and Normative Approaches”, at the Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, May 12-13, 2017, as well as Sara Kalm, Jan Teorell, and the editors and reviewers of Citizenship Studies, for helpful comments and suggestions. Pia Lonnakko provided excellent research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Agustín Goenaga

Agustín Goenaga is a Research Fellow at the Department of Political Science, Lund University, and the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities. His research focuses on democratic theory and political development. His work has been published or is forthcoming at Comparative Political Studies, Politics & Society, Politics & Gender, and Oxford University Press.

Notes

1. The author thanks an anonymous reviewer of Citizenship Studies for highlighting this point.

2. Renshon (Citation2009) and Hayduk (Citation2012) provide lists of arguments that are typically used to support or oppose the enfranchisement of non-citizens. They thus offer a good first glimpse of the normative content of those conflicts. Also see Walter, Rosenberger, and Ptaszynska (Citation2013) on youngsters’ views about criteria for enfranchisement in Austrian cities, and Coll (Citation2011) on activists’ discursive strategies in campaigns for non-citizen voting rights in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

3. There is, of course, a large literature on discursive frames that spans several disciplines (for a classical review, see Benford and Snow Citation2000). Benford and Snow’s conceptualization of frames has also been used on previous work on the discursive strategies of movements to enfranchise non-citizens (Jacobs Citation1998; Pedroza Citation2013). See, for instance, Pedroza’s reformulation of Benford and Snow’s definition of frames as ‘concrete signifying devices and strategies of agents immersed in a context of interpretive struggles’ (Pedroza Citation2013, 869).

4. See McCammon (Citation2012) for a similar analysis of U.S. women’s jury movements.

5. We were able to run keyword searches for the entire period in both legislative chambers in France. For Sweden, only the transcripts of debates after 1990 were machine-readable, so for previous years we only coded statements voiced during legislative sessions specifically devoted to non-citizen voting rights. We did not find major differences in actors’ positions and frames between the arguments they voiced in debates on specific bills and those uttered in debates on other issues. Therefore, the missing observations for Sweden prior to 1990 are unlikely to bias our findings.

6. The data is available through the author's website: www.agustingoenaga.com.

7. We initially included a category based on concerns about public resources as a frame against non-citizen voting rights, but we did not find any observations in either country, so it is not included in the following discussion.

8. Of course, the number of arguments is only useful to get a sense of the saliency of a particular initiative relative to other debates in the same country but not for cross-country comparisons, since institutional differences – e.g. a bicameral or unicameral parliament, the number of parliamentary seats, the length of the parliamentary calendar, etc. – make such comparisons meaningless.

References

- Abizadeh, A. 2008. “Democratic Theory and Border Coercion No Right to Unilaterally Control Your Own Borders.” Political Theory 36 (1): 37–65. doi:10.1177/0090591707310090.

- Andres, H. 2013. “Le droit de vote des résidents étrangers est-il une compensation à une fermeture de la nationalité? Le bilan des expériences européennes.” Migrations Société 25 (146): 103–115. doi:10.3917/migra.146.0103.

- Archibugi, D., D. Held, and M. Köhler. 1998. Re-Imagining Political Community: Studies in Cosmopolitan Democracy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Arrighi, J.-T., and R. Bauböck. 2017. “A Multilevel Puzzle: Migrants’ Voting Rights in National and Local Elections.” European Journal of Political Research 56 (3): 619–639. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12176.

- Bateman, D. A. 2018. Disenfranchising Democracy: Constructing the Electorate in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Beckman, L. 2006. “Citizenship and Voting Rights: Should Resident Aliens Vote?” Citizenship Studies 10 (2): 153–165. doi:10.1080/13621020600633093.

- Benford, R. D., and D. A. Snow. 2000. “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26: 611–639. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611.

- Benhabib, S. 2004. The Rights of Others: Aliens, Residents, and Citizens. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Bohman, J. 2007. Democracy across Borders: From Dêmos to Dêmoi. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Caul, M. 2001. “Political Parties and the Adoption of Candidate Gender Quotas: A Cross-National Analysis.” The Journal of Politics 63 (4): 1214–1229. doi:10.1111/0022-3816.00107.

- Coll, K. 2011. “Citizenship Acts and Immigrant Voting Rights Movements in the US.” Citizenship Studies 15 (8): 993–1009. doi:10.1080/13621025.2011.627766.

- Conklin, A. L. 1997. A Mission to Civilize: The Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa, 1895-1930. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Earnest, D. C. 2008. Old Nations, New Voters: Nationalism, Transnationalism, and Democracy in the Era of Global Migration. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- Earnest, D. C. 2014. “Expanding the Electorate: Comparing the Noncitizen Voting Practices of 25 Democracies.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 16 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1007/s12134-014-0334-8.

- Earnest, D. C. 2015. “The Enfranchisement of Resident Aliens: Variations and Explanations.” Democratization 22 (5): 861–883. doi:10.1080/13510347.2014.979162.

- Eurostat. 2017. “Migration and Migrant Population Statistics.” http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics

- Goodin, R. E. 2016. “Enfranchising All Subjected, Worldwide.” International Theory 8 (3): 365–389. doi:10.1017/S1752971916000105.

- Hammar, T. 1977. ““The First Immigrant Election” : Abbreviated Version of a Preliminary Report in Swedish on the Participation of Immigrants in the 1976 Swedish Local and Regional Elections.” Report/Commission on Immigration Research; 4, Stockholm: Commission on immigration research [Expertgruppen för invandrarforskning] (EIFO), Ministry of labour [Arbetsmarknadsdep.], (Stockholm : Åberg offset).

- Hayduk, R. 2012. Democracy for All: Restoring Immigrant Voting Rights in the U.S. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Held, D. 1995. Democracy and the Global Order: From the Modern State to Cosmopolitan Governance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Jacobs, D. 1998. “Discourse, Politics and Policy: The Dutch Parliamentary Debate about Voting Rights for Foreign Residents.” The International Migration Review 32 (2): 350–373. doi:10.2307/2547187.

- Jacobs, D. 1999. “The Debate over Enfranchisement of Foreign Residents in Belgium.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 25 (4): 649–663. doi:10.1080/1369183X.1999.9976708.

- Jacobson, D. 1996. Rights across Borders: Immigration and the Decline of Citizenship. BRILL. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Jensen, K. K., C. Fernández, and G. Brochmann. 2017. “Nationhood and Scandinavian Naturalization Politics: Varieties of the Civic Turn.” Citizenship Studies 21 (5): 606–624. doi:10.1080/13621025.2017.1330399.

- Joppke, C. 1998. Challenge to the Nation-State: Immigration in Western Europe and the United States. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Justwan, F. 2015. “Disenfranchised Minorities: Trust, Definitions of Citizenship, and Noncitizen Voting Rights in Developed Democracies.” International Political Science Review 36 (4): 373–392. doi:10.1177/0192512113513200.

- Keith, D. J., and T. Verge. 2018. “Nonmainstream Left Parties and Women’s Representation in Western Europe.” Party Politics 24 (4): 397–409. doi:10.1177/1354068816663037.

- Knudsen, T., and B. Rothstein. 1994. “State Building in Scandinavia.” Comparative Politics 26 (2): 203–220. doi:10.2307/422268.

- Koopmans, R., and I. Michalowski. 2017. “Why Do States Extend Rights to Immigrants? Institutional Settings and Historical Legacies across 44 Countries Worldwide.” Comparative Political Studies 50 (1): 41–74. doi:10.1177/0010414016655533.

- Koopmans, R., and P. Statham. 1999a. “Challenging the Liberal Nation‐State? Postnationalism, Multiculturalism, and the Collective Claims Making of Migrants and Ethnic Minorities in Britain and Germany.” American Journal of Sociology 105 (3): 652–696. doi:10.1086/210357.

- Koopmans, R., and P. Statham. 1999b. “Ethnic and Civic Conceptions of Nationhood and the Differential Success of the Extreme Right in Germany and Italy.” In How Social Movements Matter, edited by M. Giugni, D. McAdam, and C. Tilly. pp. 225-251. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Koopmans, R., P. Statham, M. Giugni, and F. Passy. 2005. Contested Citizenship: Immigration and Cultural Diversity in Europe. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Lappin, R. 2016. “The Right to Vote for Non-Resident Citizens in Europe.” International & Comparative Law Quarterly 65 (4): 859–894. doi:10.1017/S0020589316000336.

- Lefebvre, E. L. 2003. “Republicanism and Universalism: Factors of Inclusion or Exclusion in the French Concept of Citizenship.” Citizenship Studies 7 (1): 15–36. doi:10.1080/1362102032000048684.

- McAdam, D., J. D. McCarthy, M. N. Zald, and N. Mayer Zald. 1996. Comparative Perspectives on Social Movements: Political Opportunities, Mobilizing Structures, and Cultural Framings. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- McCammon, H. J. 2001. “Stirring up Suffrage Sentiment: The Formation of the State Woman Suffrage Organizations, 1866-1914.” Social Forces 80 (2): 449–480. doi:10.1353/sof.2001.0105.

- McCammon, H. J. 2012. “Explaining Frame Variation: More Moderate and Radical Demands for Women’s Citizenship in the U.S. Women’s Jury Movements.” Social Problems 59 (1): 43–69. doi:10.1525/sp.2012.59.1.43.

- McCammon, H. J., K. E. Campbell, E. M. Granberg, and C. Mowery. 2001. “How Movements Win: Gendered Opportunity Structures and U.S. Women’s Suffrage Movements, 1866 to 1919.” American Sociological Review 66 (1): 49–70. doi:10.2307/2657393.

- McConnaughy, C. M. 2013. The Woman Suffrage Movement in America: A Reassessment. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Näsström, S. 2011. “The Challenge of the All-Affected Principle.” Political Studies 59 (1): 116–134. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00845.x.

- Neuman, G. L. 1991. “We are the People: Alien Suffrage in German and American Perspective.” Michigan Journal of International Law 13: 259–335.

- Owen, D. 2012. “Constituting the Polity, Constituting the Demos: On the Place of the All Affected Interests Principle in Democratic Theory and in Resolving the Democratic Boundary Problem.” Ethics & Global Politics 5 (3): 129–152. doi:10.3402/egp.v5i3.18617.

- Pedroza, L. 2013. “Policy Framing and Denizen Enfranchisement in Portugal: Why Some Migrant Voters are More Equal than Others.” Citizenship Studies 17 (6–7): 852–872. doi:10.1080/13621025.2013.834140.

- Pettit, P. 2012. On the People’s Terms: A Republican Theory and Model of Democracy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Renshon, S. A. 2009. Noncitizen Voting and American Democracy. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Riksdagsförvaltningen. 1975. “Regeringens Proposition 1975/76:23 Om Kommunal Rösträtt För Invandrare.” http://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/proposition/om-kommunal-rostratt-for-invandrare_FZ0323

- Rosanvallon, P. 2007. The Demands of Liberty: Civil Society in France since the Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Rovan, A. 2014. “Droit de Vote Des Étrangers : Hollande «ne Renonce Pas».” Le Figaro, July 14. https://www.lefigaro.fr/politique/2014/07/14/01002-20140714ARTFIG00173-droit-de-vote-des-etrangers-hollande-ne-renonce-pas.php

- Santana, A., and S. Aguilar. 2018. “Bringing Party Ideology Back In: Do Left-Wing Parties Enhance the Share of Women MPs?” Politics & Gender 1–25. doi:10.1017/S1743923X1800048X.

- Schmid, S. D., L. Piccoli, and J.-T. Arrighi. 2019.“Non-Universal Suffrage: Measuring Electoral Inclusion in Contemporary Democracies.” European Political Science, February. doi:10.1057/s41304-019-00202-8.

- Skinner, Q. 1998. Liberty Before Liberalism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Smith, R. 2008. “The Principle of Constituted Identities and the Obligation to Include.” Ethics & Global Politics 1 (3): 139–153. doi:10.3402/egp.v1i1.1860.

- Snow, D. A., and R. D. Benford. 1988. “Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participant Mobilization.” International Social Movement Research 1 (1): 197–217.

- Song, S. 2009. “Democracy and Noncitizen Voting Rights.” Citizenship Studies 13 (6): 607–620. doi:10.1080/13621020903309607.

- Sørensen, Ø., and B. Stråth. 1997. The Cultural Construction of Norden. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press.

- Soysal, Y. N. 1994. Limits of Citizenship: Migrants and Postnational Membership in Europe. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Teney, C., and D. Jacobs. 2016. “Le droit de vote des étrangers en Belgique : Le cas de Bruxelles.” Migrations Société 114 (December): 151–168.

- Toral, G. 2015. “Franchise Reforms in the Age of Migration: Why Do Governments Grant Voting Rights to Noncitizens?” SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2604981, Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2604981

- Triandafyllidou, A. 2014. “Reform, Counter-Reform and the Politics of Citizenship: Local Voting Rights for Third-Country Nationals in Greece.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 16 (1): 43–60. doi:10.1007/s12134-014-0343-7.

- Walter, F., S. Rosenberger, and A. Ptaszynska. 2013. “Challenging the Boundaries of Democratic Inclusion? Young People’s Attitudes about the Distribution of Voting Rights.” Citizenship Studies 17 (3–4): 464–478. doi:10.1080/13621025.2012.707008.

- Wilder, G. 2005. The French Imperial Nation-State: Negritude and Colonial Humanism between the Two World Wars. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.