ABSTRACT

Drawing on newly incorporated citizens’ experiences, interviews with numerous state officials, and field observations in the former border enclaves of India inside Bangladesh after their exchange in 2015, I contend that the state of Bangladesh took extraordinary measures to incorporate its new citizens. Such exceptional measures resulted in a category of citizens that cannot be fully grasped by the existing citizenship vocabulary. In this paper I therefore offer the concept of showcase citizens. Showcase citizens represent an exceptionally treated group of citizens who became subjects to special attention from the state in certain spaces at a specific time. The key to our understanding of such ‘exceptions’ and the unique response from the Bangladesh state, I argue, lies in placing the enclaves within the broader context of post-colonial South Asia, specifically in relation to the imagination of nation and territory, sovereignty, (performative) governance, and state-making. As such, showcase citizens becomes both an analytical tool – which links the imagination of territory, sovereignty, and citizenship in post-colonial South Asia – and a technique of performative governance that combines the formal with the informal.

Introduction

Having worked on my fieldnotes and organized the day’s work, I was almost ready to go to bed in my hotel room in Patgram, Bangladesh. It was after ten o’clock that I heard a knock on my door. Assuming it would be my research assistant, I opened it, and to my surprise one of the schoolteachers I had interviewed earlier was standing in front of me! Unsure how to react, I invited him in. Apologizing for his sudden appearance, he said he wanted to talk about some ‘personal’ issues. Even more surprised, I allowed him in, and we began a late-night conversation. It turned out he was planning to sue the government, demanding that it bring the former enclave schools under the Monthly Pay Order (MPO).Footnote1 The MPO was a recurring issue in the interviews I had conducted earlier that day. However, when asked why he thought the judge would even consider the case given the clear policies concerning who was incorporated under the MPO, his answer was.

Why not? We’re the former enclave residents. We’re special. The government is making a lot of exceptions for us. They’re helping us with all our problems; why then would they not think about us [teachers]? (emphasis and explanation added).

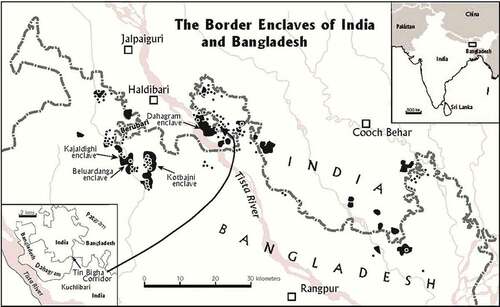

The emotional teacher was arguing that they had the right to be treated exceptionally because they were former enclave residents. At the same time he was arguing that the state should make an exception for them, referring to other instances when former enclave residents had received special treatment from the state. As shows, these enclaves were small pieces of land that belonged to one state but were completely surrounded by the territory of the other: Indian enclaves were located inside Bangladesh and vice versa (van Schendel Citation2002).

Figure 1. Former border enclaves of Bangladesh and India (source Jones Citation2009b, reproduced with permission).

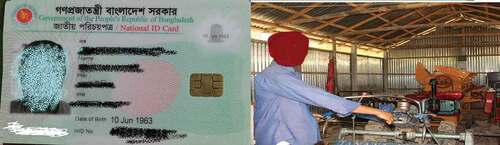

Figure 2. A smart national ID card (on the left) and a farmer showing the machinery in one of the Farmers’ Clubs (on the right).

Although the origin of the enclaves is traced to the precolonial era in 1713, they gained international status only in 1947 after the Indian subcontinent was divided between two sovereign states, India and Pakistan (Whyte Citation2002). Before the partition of the subcontinent the enclaves posed little challenge to the lives and mobilities of their residents, because their boundaries were enforced only for tax collection (Ferdoush Citation2014; van Schendel Citation2002). However, the scenario began to change quickly with the introduction of passports in 1952, a brief war between the two states in 1965, and frequent conflicts over undemarcated territories (Sur Citation2021). Another major geopolitical shift occurred in 1971 as East Pakistan declared independence and emerged as the sovereign state of Bangladesh, the youngest in South Asia. The newly independent state of Bangladesh inherited all the enclaves from Pakistan and now shared them with India. Soon after, in 1974, Bangladesh and India signed a treaty to exchange their enclaves and agreed to merge them with the respective host state’s territories. The treaty became known as the 1974 Land Boundary Agreement (LBA). However, numerous reasons and changing political scenarios both in Bangladesh and India meant the treaty was not fully ratified until 2015 (for details see Ferdoush Citation2019a).

During this period enclave residents lived in limbo, surrounded by a sovereign state that did not recognize them as citizens. Furthermore, India’s more stringent bordering practices, including its deployment of lethal forces at the border and the construction of barbed wire fences along its entire border with Bangladesh, effectively disconnected enclave residents from their ‘home’ states. Such a precarious existence stripped them of their citizenship rights, legal protection, and other essential services such as education and health, which turned them into a de facto stateless population (Shewly Citation2013; Cons Citation2016; Ferdoush Citation2019b). A joint headcount by Bangladesh and India suggests that the total number of enclave residents living across the border was almost 55,000 at the time of the exchange. In accordance with the 1974 LBA enclave residents were given an option to choose their state of citizenship during the exchange; they could either stay where they were and opt for a formal change in their citizenship status or move to their ‘home’ countries as citizens. Almost 37,000 former Indian enclave residents decided to stay in Bangladesh and became Bangladeshi citizens in 2015 (Ferdoush and Jones Citation2018). After the enclaves were merged with the surrounding state territories and residents were accepted as citizens, the state of Bangladesh undertook unprecedented state- and nation-making measures in these enclaves (Ferdoush Citation2021a). Such measures involved exceptional treatment of the newly incorporated citizens through both formal and informal mechanisms. Drawing on the experience of the newly incorporated citizens, their neighbors who were regular Bangladeshi citizens, interviews with numerous state officials, field observations, and analyses of government documents and newspaper reports, I argue that such treatment resulted in a unique type of citizen with exceptional experiences who cannot be comprehensively grasped by the existing citizenship vocabulary.

I therefore offer the concept of showcase citizens to refer to a category of citizens who are treated exceptionally by the state in ensuring they get access to and enjoy the rights that come with the identity of being citizens. At the same time the stateFootnote2 uses such citizens to conceal the unequal treatment of its other citizens and the structural violence fashioned by numerous state apparatuses. As such, the analytical tool of showcase citizens is best understood as an intentional combination of formal and informal arrangements – a performativity of state governance (Butler Citation2011; Ding Citation2020) – which is used to produce and foster an image of a caring state that actively helps all its citizens, irrespective of their socioeconomic and political conditions. In reality, however, it does not, because the state does not demonstrate such ‘care’ for all its citizens. Citizenship is one of the most widely studied yet broadly contested concepts across the social sciences (Staeheli Citation2011). This is especially true in post-colonial South Asia, as many argue that the colonized populations achieved independence as collective groups rather than as individual free citizens (Kabeer Citation2002; Redclift Citation2016). It is therefore imperative that we pay close attention to specific political discourses and historical moments through which unique and particular state–citizen relations are produced (Hansen Citation1999; Redclift Citation2016). In this sense, to paraphrase Cons (Citation2016, 20), one might thus do well to view showcase citizens both as an analytical tool – which links the imagination of territory, sovereignty, and citizenship in post-colonial South Asia – and a technique of performative governance that combines the formal with the informal.

Data collection involved two phases for this research. The first phase was conducted in June and July of 2015, as the enclaves were scheduled to be exchanged and merged in August. During this phase of ethnographic research, I conducted 13 in-depth interviews with former enclave residents and two government officials across four enclaves in northern Bangladesh. The second phase involved 12 months of ethnographic research in eight of the biggest enclaves across the districts of Rangpur, Lalmonirhat, and Panchagarh in Bangladesh. During this period I conducted 57 interviews and six focus groups with newly incorporated citizens, 10 interviews with regular Bangladeshi citizens, and 22 interviews with government officials at different levels. In doing so, I stayed and moved in and around the enclaves, took detailed fieldnotes, observed the daily lives of enclave residents, and participated in many events with them. All interviews were conducted in Bengali, and I transcribed them with the help of my research assistant in English (for details see Ferdoush Citation2020).

The rest of the paper is divided into four sections. In the first I delve into a discussion of showcase citizens. In doing so, I situate the concept within the existing scholarship to demonstrate how it is related to yet distinct from the existing vocabularies of citizenship. In the second section, drawing on interviews and observations from the field, I shed light on the creation and experiences of showcase citizens. As such, this section offers a nuanced description of how through formal and informal arrangements unique privileges were offered to a select group of citizens and captures their experiences due to such arrangements. The focus then shifts to how Bangladesh used the former enclave residents in fostering an image of a caring state as it showcased them on national and international platforms. In conclusion, by summarizing these arguments I suggest the concept’s further applicability beyond the scope of the current research.

Showcase citizens

My use of the term showcase citizens stems both from the unique context of the current research and the slippery nature of the idea of citizenship itself. Showcase citizens is a unique category that was warranted by various ‘exceptions’ which preceded and followed the exchange of the former border enclaves. In this context showcase citizens are those who were deemed eligible for ‘exceptional’ treatment by the state, that is, the former border enclave residents of India accepted as regular Bangladeshi citizens. I contend that the key to our understanding of such ‘exceptions’ and the unique response from the state of Bangladesh lies in placing the enclaves within the broader context of post-colonial South Asia, specifically in relation to the imagination of nation and territory, sovereignty, (performative) governance, and state-making.

Since their inception, the former border enclaves had existed as extraterritorial spaces that did not fit the cartographic imagination of a post-colonial nation-state, that is, the imagination of a ‘geo-body’ (in the sense of its visual representation) congruent with its territory (the imagined space that contains that nation) (Cons Citation2016; Winichakul Citation1994). In this respect cartography refers to the practice of justifying an imagined nation-state within certain boundaries with attached meanings, contents, histories, and trajectories. Accordingly, the cartographic representation of a nation in a map essentially becomes nothing less than ‘the social and political production of nationality itself’ (Krishna Citation1994, 508). This is especially applicable to post-colonial South Asia, where nation states were created overnight through cartographic scissoring, resulting in nations that are forever suspended between a state of ‘former colony’ and ‘not-yet-nation’ (Krishna Citation1994, 508). As a result, many argue that the imagination of a nation and the production of its territory have ‘succumbed to the lure of the map’ (Ramaswamy Citation2008, 825): In other words, the territory of a nation seems to make sense only within national maps (Ludden Citation2003). Consequently, the idea of inside and outside – who and what is included in and excluded from the nation – is also greatly determined by the cartographic boundaries of that nation (Krishna Citation1994). To this end the former border enclaves assumed a contradictory position. On the one hand they were part of the national territory and hosts of fellow nationals; on the other they were an irritation to the imagination of a seamless national boundary. As such, they became sources of ‘cartographic anxiety’ for the home state, because they existed beyond national boundaries and were territorially surrounded by another sovereign state. Concurrently, they remained ‘spaces of desire’ – spaces that existed but were not fully incorporated within the nation’s geo-body – for the host state (Krishna Citation1994). Such a dual role turned the enclaves into ‘amplified’ territories – territories that gained an inflated significance in national rhetoric given their practical use or size (Cons Citation2016).

Although such an amplified status continued to make the former enclaves highly relevant to the debates on national territory and citizenship in both Bangladesh and India, their people were ‘forgotten’ (Jones Citation2010). Cons captures this situation precisely as he writes that these became spaces about which ‘the center thinks with intense passion, though not necessarily with great care’ (Cons Citation2016, 21). In practice enclaves therefore became abandoned spaces outside the borders of the home state that did not maintain any channel of formal connection with them, and extrajudicial spaces inside the boundaries of the host state, which did not recognize their residents as rights-bearing citizens. In capturing this duality of in/exclusion and drawing on the Agambenian framework of violence and exception (Agamben Citation1998), Reece Jones (Citation2009a) views the former enclaves as being in a state of ‘permanent exception’, in which they remained excluded from the protection of the sovereignFootnote3 but were made occasional victims of its violence. Following a similar logic, Hosna Shewly captures the former enclaves as ‘abandoned spaces’ that contained ‘bare lives’ (Shewly Citation2013). These were spaces where ‘exception’ became part of daily life – and often the rule (Jones Citation2009b). However, such ‘exceptions’ did not fade overnight simply because the enclaves were exchanged and merged with regular state territories, and enclave residents were brought under the protection of the sovereign. Instead, I suggest that because ‘exception’ is produced not only through and by suspending law but can also be generated by applying other mechanisms of in/exclusions, its nature assumed different forms after the enclaves were exchanged (Ferdoush Citation2021a; Martin Citation2015). The sovereign created and maintained a different kind of ‘exception’ that enabled it to favor one group of citizens over another by creating conditions which allowed ease of access to numerous state services for the former enclave residents.

As I demonstrate above, the enclaves existed as fraught territories that simultaneously worked as markers of territorial anxiety and instigators of nationalist passion. They thus never lost the states’ attention. Indeed, their significance was amplified. Their status changed, because they now became territories where ‘the unfinished business of partition continued to be worked out’ (Cons Citation2016, 168). They were brought under the project of sovereignty, their boundaries were dismantled and merged within national spaces, and their residents were accepted as members of the nation state. In James Scott’s term, these became ‘legible’ to the state for the first time when the state’s ‘vision’ of seeing itself within was being materialized (Ferdoush Citation2021a; Scott Citation1998). Furthermore, the highly publicized territorial exchange in national and international outletsFootnote4 and the ‘handing back’ of the property of the enclaves continued to keep them at the center of attention. Having been symbols of national suffering and territorial anxiety, the former enclaves became symbols of national cooperation and pride, which further fueled the extraordinary attention from the state (Ferdoush Citation2019a, Citation2021a). Thus, as the enclaves were brought under state jurisdiction and merged with regular state spaces, their residents – who were accepted as regular Bangladeshi citizens – also became the subject of extraordinary attention. This directs our focus to the embodied experiences of showcase citizenship, to which I now turn.

The idea of citizenship has been conceived from various actors’ perspectives, including (non)citizens, migrants, (il)legals, states, sovereigns, cities, and municipalities (Henderson Citation2009; Isin and Neilsen Citation2008; Ong Citation1999; Staeheli, Marshall, and Maynard Citation2016). At the same time citizenship is understood as a bundle of policies, rules, and laws that are designed to control certain groups’ access to services and therefore their privilege over others, largely regulated by the nation-state and its governing mechanisms (Joppke Citation2007; Kabeer Citation2005; Lemanski Citation2020). Since a comprehensive tracking of the vast and dynamic literature on citizenship remains beyond the scope of this paper, I focus on the ‘lived’ aspect of citizens(hip). Consequently, I apply the idea of showcase citizens as a broader lens through which to capture citizenship both as ‘lived’ experience and a bundle of rules and policies in explicitly highlighting the (in)formal and temporal aspects of open and closed opportunities for ‘particular individuals at particular moments’ (Lister Citation2007; Staeheli et al. Citation2012, 630). In this sense showcase citizenship refers to the experiences of the former enclave residents inside Bangladesh due to the exceptional treatment extended to them, both formally and informally. As such, temporality remains key to our reading of showcase citizens(hip), because such exceptional arrangements are created in certain times and spaces, allowing unique opportunities for individuals (Staeheli et al. Citation2012).

Furthermore, informality plays a significant role in creating showcase citizens. Highlighting the importance of informality in citizenship experience, Duncan McCargo argues that being citizens is not always necessarily a matter of an either/or status. Instead, it remains, to a great extent, a question of the degree to which someone can enjoy their citizenship rights – which is significantly influenced by informality (McCargo Citation2011). Similarly, in the context of Bihari camps in Bangladesh, Victoria Redclift shows that informal arrangements remain an integral part of ‘effective citizenship’ (Redclift Citation2011). According to Redclift, informal mechanisms often become difficult to distinguish from the formal but remain an inseparable aspect of the citizenship experience in Bangladesh. Especially in accessing state services, informal mechanisms and personal networks prove more effective than official identity documents. Formal identities are therefore often deemed ‘worthless’, especially for people in precarious conditions, unless there is a significant change in the condition (Redclift Citation2011, 37). I therefore suggest (and demonstrate in the next section) that informality becomes a crucial aspect of capturing the idea and experience of showcase citizens in Bangladesh.

Christian Joppke’s concept of ‘substantive citizenship’ becomes relevant in relation to this in further fleshing out the nature of showcase citizenship (Joppke Citation2007). According to Joppke, we must simultaneously approach citizenship as a status, right, and identity to have a substantial understanding of the experience. As a status, citizenship refers to the resident’s formal membership of the state and its rules of access. As a right, it is understood to be a totality of formal capacities and immunities connected with status. As an identity, citizenship includes the behavioral aspects of individual acts and the conception of the self as a member of the state and an acknowledgment of such behaviors by the state. As many demonstrate in numerous contexts, while the legal acquisition may be the first step to citizenship identity and status, it does not necessarily guarantee the rights of all citizens. Such rights must be actively ensured by the state, especially where marginal populations are concerned (Kingston Citation2017). For the status of citizenship to be ‘functioning’ – that it benefits both the state and citizens – it often requires unconventional arrangements so that people can claim basic rights and enjoy political membership, argues Lindsey Kingston (Citation2014, Citation2019). This becomes particularly applicable in the current context, in which numerous (non)state actors have played an active role in ensuring that the newly accepted citizens get to enjoy the rights associated with being a member of the polity. However, it was hardly true for the regular Bangladeshi citizens who lived around and near the former enclaves. They were not paid special attention; nor were they treated as ‘exceptional’. The newly accepted citizens ultimately attracted such treatment, I argue, because the former enclaves became the center of attention as they were going through the Bangladesh state’s ‘continually nationalizing’ project (Samaddar Citation1999).

Finally, I turn to the ‘showcase’ aspect of showcase citizens. In doing so, I place showcase citizens as a thread that connects the role of ‘performativity’ in state governance by focusing on how it is used to foster an image of a ‘caring’ state (Butler Citation2011; Ding Citation2020). I also demonstrate that showcase citizens are used in post-colonial South Asia to conceal ‘structural’ violence fashioned by numerous state apparatuses in their daily operations (Gupta Citation2012; Mathur Citation2016). I thus draw on and apply Judith Butler’s idea of ‘performativity’, suggesting that the creation of showcase citizens is a performative stance by the state through a theatrical deployment of language, media, and symbols that reiterates the ‘power of discourse to produce the phenomena that it regulates and constrains’ (Butler Citation2011, xii). Many contend that a state is a totality of performativity and theatricality through which it comes into being (Dunn Citation2010; Tripp Citation2018; Weber Citation1998). ‘Performative governance’ becomes of prime significance for the current discussion, because states are more likely to demonstrate such performativity when their capacity is low but public attention is high (Ding Citation2020).

Following this logic, I claim that the attached historical significance and (inter)national attention paid to enclave exchange meant the state of Bangladesh focused on its performativity and theatricality by extending exceptional treatment to these select groups of citizens, simultaneously ensuring that ‘little things: attitude, gestures, intentions’ were clearly expressed (Ding Citation2020, 540). It is equally true, as Ding demonstrated in another context, that the state of Bangladesh focused on showing its ‘benevolent’ side, including gestures of concern, care, and submission to the newly accepted citizens (Ding Citation2020; Ferdoush Citation2021a; Hansen Citation2001). I therefore argue that the performativity of showcasing a specific group of citizens, especially in the context of post-colonial South Asia, allows the state effectively to conceal the ‘structural violence’ fashioned through numerous state mechanisms – violence created by the state to exclude its marginal populations and in effect allow them to die, despite their inclusion in the sovereignty project (Gupta Citation2012). Gupta views the structurally excluded extreme poor as hominis sacri, who could be killed without it being considered a sacrifice (Gupta Citation2012). In response, the marginal population employs numerous tactics to navigate the fraught terrain of state governmentality and bureaucracy, which results in an informal relationship between them and the state (Chatterjee Citation2004). Yet such relations exclude those who lack minimal resources and in effect remain excluded from numerous state schemes. Similar exclusions like corruption, bribery, and the use of personal connections to curry favor among state officials are widespread in Bangladesh. The former enclave residents incorporated as citizens in 2015 were largely immune to such structural violence and exclusion, both because of the ‘exceptional’ attention and the ‘performative governance’ that prevailed in the enclaves. State officials were aware of the marginal status of the former enclave residents due to their stateless existence for the last seven decades and were instructed at the same time by different government branches to actively prioritize them in providing numerous services. Such gestures, attitudes, and intentions were frequently publicized in media outlets and were repeatedly pronounced by state officials in all my encounters with them. I therefore contend that showcase citizen(ship) becomes a tool that concurrently allows the state to performatively demonstrate its ‘benevolent’ side and conceals structural violence.

Showcase citizens in the making: experiences in the former border enclaves

In this section, I shed light on the experiences of the newly accepted citizens by focusing on the unique privileges extended to them because of their ‘exceptional’ status in the nationalist rhetoric of post-colonial South Asia and the numerous (in)formal mechanisms adopted by the state. I thus compare their experiences with the regular Bangladeshi citizens who live near and around them to affirm that a significant change in the conditions (i.e. enclaves as regular state territories) warranted privileged treatment for them. I further demonstrate that showcase citizens are used as an effective tool to conceal the structural violence embedded in the daily operations of the state of Bangladesh. It therefore testifies to my argument that post-colonial states are not shy of mixing the formal with the informal in daily governance when this serves their interests.

The most striking difference to catch my attention was the former enclave residents’ easier access to various state offices. While it is common for local leaders and connected individuals to regularly visit government offices in pursuit of services, most poor Bangladeshis in rural areas lack such access. Moreover, they are not usually treated well by the officials. Access is even less likely when it comes to directly meeting the Upazila Nirbahi Officer (UNO – the highest-ranking administrative officer in charge of a subdistrict) or the Officer in Charge (OC) of a police station. In contrast, the former enclave residents not only enjoyed a higher level of access to many state offices but were also actively encouraged by the personnel to come directly to them. Almost all the officialsFootnote5 I interviewed reported that they had been instructed by their superiors to help the new citizens in every way possible, which explained the increased accessibility. For example, one of the officers in the Upazila Land and Survey Office of Debiganj said: ‘We were told by our superiors in every meeting to help them in every way possible. They told us there was a special instruction from the government [to help them]’ (emphasis added).

Toward the end of my fieldwork I interviewed the UNO of an enclave hosting upazila and pressed the issue of access. He answered:

Yes, we are specifically instructed to assist them. … Because there is a sympathy for them, for the inhuman ways they have lived so far. So the government wants to help them to bring them forward. We are told to help them as much as we can. I take special care of the enclaves in my upazila. I keep in regular contact with the representatives from the enclaves, and the Chairman also actively helps them. They are always welcome at my office (emphasis added).

Following his answer, I asked whether they received any formal instructions from the government. He said that there were no formal written instructions, but they had been orally instructed by district officials. Every government official or public office holder with whom I spoke had similar answers, but none could produce a formal document that had explicit instructions to prioritize the newly accepted citizens. This demonstrates that the state is not shy of making informal arrangements when choosing to serve one group of citizens over another. Informality therefore remains a significant aspect of governmentality and everyday citizenship experiences in the former enclaves and their showcase citizens. In discussing a similar context in India, Partha Chatterjee contends that marginal people work informally when negotiating state mechanisms to avail of numerous facilities, and they choose how they are governed in doing so (Chatterjee Citation2004).

Most of the former enclave residents and regular Bangladeshi citizens shared similar views. The owner of the hotel where I was staying in one of the enclave hosting upazilas had been living there for the last three decades. He was one of the locals with easy access to government offices and had seen the enclave residents before and after the exchange. In sharing his view of the lives of the former enclave residents, he said:

What did they have [before the exchange]? Nothing. No one [officials] would even recognize them, let alone help them. They would also try to avoid any official or government offices. Now … ore babare [my God]! You will always see one or two of them hanging out in the office with the Chairman. They will go directly to the UNO or the OC, they don’t care! Most of the Bangladeshis [regular Bangladeshi citizens] would not imagine doing so (explanations added).

Almost echoing the hotel owner, Salam Miah, a small farmer aged forty-two from the enclave of Bashkata in Patgram shared his experiences after the exchange:

We’re really happy. We never imagined life would be like this. We’ve got more than what we expected. We lived like animals [before the exchange]. Now we live like kings. We can go anywhere we want to. We go directly to the UNO; we go directly to the police. We share our problems directly with them (explanation added).

The excerpts above suggest several significant aspects of being incorporated as citizens. First, officials are instructed by the government to actively help enclave residents in easing their access to state services. This instruction is passed informally from one level of the hierarchy to another and one office to another. Informality thus remained a significant aspect of the lived experience of the newly incorporated citizens. At the same time, it enabled state officials to extend exceptional services to a select group of citizens. Such arrangements further facilitated frequent interactions between those who administered and those who were administered through mediation, invocation of social norms, and the use of social affiliations (Berenschot and van Klinken Citation2018). Second, the ‘special instruction’ to specifically help the former enclave residents implies that state officials were aware that many state services were unlikely to reach the new citizens without the field-level officials assuming a proactive role. In other words, new citizens are likely to fall victims to structural violence unless actively taken care of by concerned (non)state actors. This further testifies to what Kingston found in other contexts; the mere formal recognition of citizenship does not guarantee effective rights to all, but the state must play a crucial role in ensuring them. The state thus often has to move beyond the relationship with its citizens as a mere provision of legal status in ways that allow state services and protection to functionally reach them (Kingston Citation2017, Citation2019).

In all my encounters with government officials and public representatives I pressed the issue of why it was necessary to specifically ensure that state services reached the former enclave residents. While most evaded the question or barely touched on it, some of my encounters yielded direct answers on the condition of full anonymity. I was not allowed to use audio recording and was often met with expressions of irritation. One of the political leaders in the subdistrict of Patgram was very surprised when I continued to press for a direct answer, saying:

Come on … if you keep asking this question, what kind of researcher are you? You know what happens in Bangladesh! … If we stop caring about them today, they will start starving tomorrow. Do you think all these facilities they are getting now would automatically reach them if we didn’t keep our eyes and ears open?

Such expressions from the political leader and interviews with other state officials suggest that it is an accepted fact among (non)state actors that the poorest of the poor are more likely to be victims of structural violence given their marginal socioeconomic and political backgrounds. For example, the UNO’s acknowledgement of a prevailing ‘sympathy’ and ‘special care’ for the former enclave residents or the frequent reference of the field-level officers to the ‘special instruction’ are clear indicators of exceptional attention. Moreover, the Patgram political leader’s answer strongly suggests that state services were unlikely to reach all the former enclave residents without an active role played by (non)state actors. On the contrary, the experiences of the hotel owner above and Ali Ahmed below demonstrate that such privileges were not extended to regular Bangladeshi citizens. Life for them therefore remained the same struggle of daily negotiations with numerous state mechanisms.

Another aspect of exceptional treatment is evident in how former enclaves were connected to the national power grid. The enclaves had existed without any power supply from Bangladesh until they were exchanged. Sheikh Hasina, the prime minister of Bangladesh, was scheduled to visit the former enclave of Dasiar Chhara on 15 October 2015, almost two and a half months after the exchange. On her visit she inaugurated power supply to Dasiar Chhara (Rahman and Khan Citation2015a). This was exceptional: In rural Bangladesh, getting an electricity connection would normally require residents to wait months or sometimes years. Dasiar Chhara was connected to the power grid within two and a half months. One of the engineers overseeing power supply to Dasiar Chhara shared his experience. He said they were notified of the prime minister’s visit and her plans to inaugurate electricity supply only about two months ahead of schedule. Given the short notice, they therefore invested all their resources and efforts in connecting Dasiar Chhara to the power grid. He also mentioned that he had never seen any village in Bangladesh connected to the power grid so quickly.

‘Speed money’ (a bribe to speed up the bureaucratic process) is an open secret in Bangladesh associated with getting an electricity connection. The process also involves complicated paperwork. Furthermore, if a house is far from the existing power line, it will probably take more time, more speed money, and further paperwork. As a result, navigating such an intimidating and expensive process remains a nightmare for most poor Bangladeshis. Even if one finds a way to get the paperwork done and put the speed money in the right place, it takes months to finally get a connection. However, in the former enclaves getting an electricity connection was easy, because the concerned officials actively ensured that all residents seeking a power supply were connected to the grid. Abul Hossain, a small farmer in his late sixties and one of the former enclave residents of Dahala Khagrabari, shared his experience:

This is like a dream [come true] for us. All of us got electricity in our houses. We got electricity within a year of the exchange. … The village beside us got electricity after us [although that was a regular Bangladeshi village]. In fact, they got the connection because we were getting connected (explanations added).

Following his answer I asked him if they had had to bribe anyone to get the connection. With a vigorous shake of his head he said:

No, no, we didn’t have to spend a single taka (the Bangladeshi currency) except for the meter. High-level officials came here and told us to let them know directly if anyone asked for money. Normally, you would have to spend thousands of taka to get a connection. We didn’t have to spend anything. … Even the house at the edge of the enclave got electricity. They erected three or four poles just to connect that house.

However, it was dramatically different for regular Bangladeshi citizens living around the enclave. Ali Ahmed, a regular Bangladeshi citizen who lives close to Dasiar Chhara and owns a small tea stall, shared his experience of getting a new connection for a house that his son-in-law had recently built near the enclave. During my interview with Ahmed he frequently referred to the bishesh subidha (special facilities) that the former enclave residents were given. I asked him to give an example of the ‘bishesh subidha’ to which he was referring. In response, he shared his experience of getting a new connection for his son-in-law’s house:

Look, these poles and the lines (pointing at the electricity poles and lines in Dasiar Chhara) you are looking at, they didn’t have to spend a single paisa [cent] on them. Sarkar [the government] came to their houses and gave them electricity. Now, when my son-in-law built a house and needed an electricity connection, we had to go through everything. … And of course, you know, give them cha khawar taka [an expression used to mean a bribe]. After roaming around in the office for about a year, we finally got electricity (explanations added).

Not only are access easier and services quicker, but the former enclave residents are also actively prioritized in the distribution of government aid and allowances. Guchho Gram affords an example. Guchho Gram is a model village established by the state of Bangladesh that consists of 30 tin-made houses on a 1.2-acre plot which provide housing for the marginal poor who lack the resources to afford a house in the former enclave of Kotvajni, in Panchagarh district. In addition to housing, 16 households in Guchho Gram were allocated VGD (Vulnerable Group Development) cards that provided them with 30 kilograms of rice each month. Two of the inhabitants were given an elderly allowance, and two were given a widow’s allowance. In this respect, Matiar Rahman, a landless farmer in the former enclave who received a house in Guchho Gram and a rickshaw van from the local administration to earn a living, shared his story. He said:

We’re all really happy and pray for Hasina [PM Sheikh Hasina]. She really cares about us. She gave us a country, gave us an identity, gave us a home. Before her no one even raised a finger for us.

I found similar cases elsewhere including Dasiar Chhara. The local administration allocated 2,950 VGD cards for Dasiar Chhara alone, while there were only 1,600 eligible inhabitants for such aid (interview with an official at the UNO Office). Aslam Ahmed, a 37-year-old regular Bangladeshi citizen who ran a small tea stall near Dasiar Chhara, shared his views over a cup of tea:

Look brother, I’ve been living here since I was born. No one cared about these people (referring to the enclave residents) even a couple of years ago. Now the government has gone crazy (akhon sorkarer matha kharap hoia gase). What aren’t they giving them? … They don’t find enough people in Dasiar Chhara to give [VGD]cards to. In contrast, look at us! Some people don’t get a single card, even spending day after day just making requests to the Chairman or the Member!

The interview excerpts from officials, former enclave residents, and regular Bangladeshi citizens clearly demonstrate the active and exceptional role assumed by state and nonstate actors in helping the newly accepted citizens. It also suggests that the treatment of regular Bangladeshi citizens with similar socioeconomic statuses remained as usual. VGD cards were scarce, and no (non)state actors actively reached out to ensure they got one. Life continued as a daily struggle of navigating complex state mechanisms for them. Such instances reaffirm that citizenship remains merely a symbolic status for the marginal populations until they either find a way to negotiate several state mechanisms or are actively helped by (non)state officials (Gupta Citation2012).

Drawing on the instances above, I contend that while the exceptional treatment and active role of the state result in a privileged group, they create further exclusion by promoting it over others and thus marginalizing them further. In this case marginalization refers to the ‘injustice through which certain subjects are denied access to the common resources of a political order’ (Turner Citation2016, 148). The experience of Ali Ahmed and his son-in-law’s effort to get an electricity connection or the lack of enough VGD cards for regular Bangladeshi citizens testify to that marginalization. Such marginalization excludes resource-poor citizens, both from their counterparts who are actively helped by the state and from other citizens who possess resources.

Exceptional service to or active prioritization of the former enclave residents is also common in other aspects of public life, especially in education, voting, and the agricultural sector. Most of the former enclave residents could never legally obtain a government-issued identity card like a passport or national identity card. However, after the exchange one of the first documents that they actively sought was a national identity card. Bangladesh also made a list of voters in all the enclaves within the first six months of the exchange so that they could vote in local, and later national, elections. The Upazila Election Commission Office was instructed to develop the voter list immediately after the exchange and to provide enclave residents with National Identity Cards. Bangladesh launched a new biometric ‘smart’ identity card with fingerprint and retina recognition technology in late 2016. The pilot project was launched in a few of the upazilas in Bangladesh. Fulbari upazila in Kurigram was one, and among the people in Fulbari upazila, Dasiar Chhara residents were the first to get the smart card. The Chief Election Commissioner of Bangladesh visited Fulbari and inaugurated the project with Dasiar Chhara residents. All of them received smart ID cards before anyone in their district or region (interview with the Election Commissioner of Fulbari). The pilot project concurrently illustrates the state of Bangladesh’s vision of creating ‘legible’ spaces by bringing the population under its official registrar (e.g. voter list) and remains a signpost of performative governance in which enclave residents were chosen over regular Bangladeshi citizens for the distribution of smart ID cards.

The former enclave residents also enjoyed a higher degree of privilege when it came to farming. Before the exchange enclave farmers were not officially allowed any government subsidized fertilizer, seed, or water for irrigation, because these were limited to citizens. After the exchange enclave farmers were specifically taken care of by the Upazila Krishi Office (Subdistrict Agriculture Office). I came across numerous ‘Farmers’ Clubs’ in the former enclaves which were small cooperatives established after the exchange. They not only helped the local farmers in obtaining government subsidized fertilizer and seed but also owned several farming tools such as power tillers, seed sowing machines, harvesters, and so on. Upazila Krishi Office donated these machines to the club so that its members could rent them cheaply (demonstrated in ). The officials also helped them establish and operate the club. An interview with the president of the Bashkata Farmers’ Club, Ainul Islam, who ran a small shop in the enclave, revealed how the club was created and operated.

After we became Bangladesh [meaning after the exchange], the agriculture officers started visiting the enclave. They asked us to go to the upazila office and shared information about many training courses they provided for free. They also told us to form a club with the local farmers and taught us how to run it. So I took the initiative—I founded the club, and almost all the farmers are now members (explanation added).

The exceptional treatment of the former enclave residents and the active role of numerous government officers in helping them are not only limited to the lower administrative levels. High-ranking officials and public figures often expressed such intentions in their speeches. For example, the prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, made this clear when she visited the former enclave of Dasiar Chhara. In her speech during her visit on 15 October 2015, she said:

You are the flowers of Fulbari.Footnote6 We have got you amongst us. From now on no one will call you enclave dwellers. You will not be deprived anymore (emphasis added, translated from Rahman and Khan Citation2015b).

Showcasing it to the nation and beyond

On 4 March 2016, at the inaugural ceremony of the seventh Bangladesh–India Friendship Dialogue, the Foreign Minister of Bangladesh, Abul Hassan Mahmood Ali, said:

The enclaves have been exchanged and people’s movement has been completed without any difficulty. Implementation of remaining parts of LBA is also going on in a smooth and time-bound-manner. By so doing we have set examples to the rest of the world (Ministry of Foreign Affairs Citation2016).

The government of Bangladesh and India capitalized on the successful exchange of enclaves by fostering the image of a caring state, as the territorial exchange gained considerable attention on national and international platforms. The statement of the Foreign Minister of Bangladesh demonstrates that they showcase the exchange as an ‘example’ for the ‘rest of the world’. Drawing on such instances from both Bangladesh and India, in this section I demonstrate how the enclave exchange and the newly incorporated citizens are showcased in the media and in bilateral documents. Additionally, I show that the ruling party in Bangladesh, the Awami League, took advantage of the special treatment of the former enclaves for political campaigns and used it as an effective tool against the opposition parties. I thus contend that it also capitalizes on the ‘performativity’ of good governance through a theatrical deployment of language, media, and symbols by selectively highlighting its benevolent aspects (Butler Citation2011; Ding Citation2020).

As the exchange gained pace after the 2009 general elections in both countries, India and Bangladesh began to acknowledge the suffering of the people living in these enclaves and adopted a sympathetic approach toward them (Ferdoush Citation2019a). For example, the Land Boundary Agreement published by the Ministry of External Affairs of India states:

The exchange of the enclaves will mitigate major humanitarian problems as the residents in the enclaves and others on their behalf had often complained of the absence of basic amenities and facilities (Ministry of External Affairs Citation2015b, 25).

Moreover, on their website the Ministry of External Affairs elaborately presents the arrangement that the government had made for those who decided to move to India from Bangladesh:

The State Government of West Bengal has put in place elaborate arrangements for their stay in temporary resettlement camps and for issue of necessary documentation to them. Facilities made available at the camps include tin houses, common dining hall and kitchen, community toilets, anganwadi centre, playground equipment, etc. Arrangements for bank account opening, biometric enrolment, currency exchange and relief kit for each family have been made (Ministry of External Affairs Citation2015a).

Those who decided to move to India from Bangladesh, with more media attention, gained special status as ‘Indians coming back to their homes’. I therefore contend that such arrangements for the returning group enabled the state of India to foster an image of a caring state by showcasing its active aid for resource-poor citizens.

Similarly, Bangladesh occasionally showcased the enclave residents to create an image of a caring state both in national and international media, as government officials, including the prime minister, frequently mentioned the unforeseen arrangements made for new citizens. For example, just before the exchange in May 2015, a minister of the government of Bangladesh, who wished to remain anonymous, told the Dhaka Tribune that the prime minister was very keenly aware of the inhumane living conditions in the enclaves and directed concerned ministries to ensure their welfare. According to the cabinet member prime minister Sheikh Hasina

… directed the related ministry to ensure welfare of the people of the enclaves, specially ensure health facilities and education. She instructed that roads be constructed for smooth communication and the homeless be provided shelter. She also talked about providing employment opportunities for them (Dhaka Tribune Citation2015).

Such an unnamed yet detailed description of the meeting and sharing of the prime minister’s intentions with the media indicates that the government actively promoted their activities and intentions of helping the enclave residents. They thus effectively showcased their sufferings before the exchange and the narrative of a changed life after they were incorporated as citizens of the country – a selective demonstration of the ‘benevolent’ side of the sovereign using language, symbols, and the media (Ding Citation2020; Hansen Citation2001).

Not only was the special treatment of the former enclave residents showcased in the national and international media to foster an image of a caring state, but the Awami League (the then-ruling party of Bangladesh) also took advantage of such an international event against its political opposition. For example, when Sheikh Hasina visited the enclaves in Kurigram immediately after the exchange, she declared that the government would do everything for the welfare of the enclave residents. She further mentioned that only the Awami League had the courage to discuss and execute the LBA. Her visit was widely covered in the national media, and Sheikh Hasina took advantage of this, adding:

Do not consider yourselves as residents of enclaves anymore. You are now citizens of this country … . we are very sincere about filling in the gaps. That’s why I came here today (emphasis added, translated from Bashar, Citation2015).

The above discussion clearly demonstrates that although the former enclave residents enjoyed a higher degree of access to and services from the state of Bangladesh, helping them smooth their experiences of citizenship, such access and services were not extended to regular Bangladeshi citizens. Similarly, special arrangements made by the West Bengal Government in India were limited to a select category of enclave residents who decided to move to India from Bangladesh. However, these arrangements were widely circulated in the media and gained national and international attention, which helped both governments foster an image of a caring state and cooperative neighbor (Ferdoush Citation2019a). The performativity of a caring state is therefore staged through the showcase citizens and expressed by showcase citizenship; as Butler has it, ‘performativity is thus not a singular “act”, for it is always a reiteration of a norm or set of norms, and to the extent that it acquires an act-like status in the present, it conceals or dissimulates the conventions of which it is a repetition’ (emphasis added, Butler Citation2011, xxi). Consequently, I postulate that the state’s active role means the experience of the citizens in the former enclaves inside Bangladesh do not represent the regular citizenship experiences of the marginalized population(s) living at the edge of the state. Instead, these are instances of an exceptionally treated group of citizens who are showcased by the state.

Conclusion

In focusing on a select group of citizens after the exchange of the former Bangladesh–India border enclaves, in this paper, I have offered the case of showcase citizens. Showcase citizens (in this instance) are the former enclave residents of India inside Bangladesh, who lived as a de facto stateless population for seven decades without official access to state services but were made subject to special treatment after the exchange of the enclaves. While alternatives may be suggested to explain the exceptional treatment of the former enclave residents because of the 1974 LBA, or because they were an easily identifiable group for such treatment, I argue that these explanations are incomplete for many reasons. First, although the treaty was signed in 1974 to solve boundary disputes and exchange the enclaves, no formal agreement was made for exceptional treatment and attention. Moreover, while India offered a welcome package for those who decided to move to India from Bangladesh, Bangladesh declared no such incentives (Ferdoush and Jones Citation2018). Rather, the agreement was to officially accept them as citizens of the state instead of treating them as enclave dwellers and to bring the enclave territories under the host state’s jurisdiction. Second, I contend that special attention was warranted not only because they were an easily identifiable group but because of the amplified history of these territories and as a by-product of state-making (Ferdoush Citation2021a, Citation2022). Showcase citizens therefore offer an example of an exceptionally treated group of citizens who became subjects of attention from the state in certain spaces at a specific time, because they found themselves at the crossroads of post-colonial territory and state-making, sovereign in/exclusion, and performative governance. Scholars have been particularly interested in the role of ‘contested’ or ‘new’ spaces in the (re)making of citizens (Gaja and Hughes Citation2017; Lemanski Citation2020; McEwan Citation2005). Showcase citizens engages with and contributes to this body of literature, because it identifies a ‘new’ space of (re)making citizenship, i.e. formerly stateless spaces that have been incorporated into a nation’s geo-body and are undergoing numerous projects of state- and nation-making (Ferdoush Citation2021a). In doing so, showcase citizenship contributes to the existing scholarship not by ‘recycling’ old concepts but by offering fresh vantage points. As Engin Isin puts it, ‘we need a new vocabulary of citizenship. … We require new concepts rather than a recycling of old categories’ (Isin Citation2009, 368).

This study is an effort to move away from the assumption that citizenship is exclusively constituted through juridico-political practices and concurrently remains a reconceptualization of the idea, focusing on spaces and temporalities that bring a myriad of actors together in materializing the imagination of a post-colonial nation-state. However, the applicability of the concept extends far beyond the scope of the current study in several respects. First, showcase citizens helps broaden the analytical lens of citizenship studies to explicitly consider ‘exception’ as a key to unearthing the role of public figures, government officials, the media, and (non)citizens in a constant (re)production of nationalism (Koch Citation2016, Citation2020), especially in post-colonial settings. At the same time such an ‘exception’ could also be fruitfully applied to further illuminate instances that are the opposite of the present case. For example, showcase citizens may often be(come) subject to exceptionally harsh state policies that undermine their citizenship claims, as happened with the infamous case of Shamima Begum, born in the UK to a Bangladeshi immigrant family. She joined an Islamic extremist group in Syria but later wanted to return ‘home’. However, this was not allowed when the UK revoked her citizenship (see Jackson Citation2021 for details).

Second, in joining others (McCargo Citation2011; Redclift Citation2011), this study firmly places informality within the study of citizenship and demonstrates the role of informality not only in constituting state–citizen relations but also in everyday state-making especially in the Global South. In so doing, it does not necessarily view informality as an anomaly. Instead, it suggests that informality can be productively applied in further studies of bureaucracy and the state both in a similar and dissimilar context in asking how formal status is transgressed through everyday claims and contests (Redclift Citation2013).

Third, showcase citizens demonstrates that the state (through different state actors) is often aware that simply granting rights and status as citizens does not automatically change lives, especially for marginal populations (Kingston Citation2017). Yet time and again it requires numerous ‘motivations’ (amplified history and media attention, for example) in doing so.

Last but certainly not least, the case of showcase citizens allows us to move to a ‘post-Agambenian’ idea of violence and exception in the sense that it demonstrates how the same sovereign treats a population that was once excluded from the sovereign’s project after it has been included. It thus joins postcolonial studies of South Asian states to affirm that unless one possesses resources or connections to negotiate different state mechanisms, one is more likely to fall prey to sovereign violence, even though they are formally included in its sovereignty project (Chatterjee Citation2004; Gupta Citation2012; Hull Citation2012). In a similar vein, it could also be an analytical lens through which to understand the creation, projection, management, and concealment of structural violence in the daily lives of subalterns and the operation of the state. Showcase citizens therefore offers both an empirical and a theoretical take on citizenship that draws on the experiences of the former enclave residents, regular Bangladeshi citizens, and numerous (non)state actors. It sheds light on the temporal and informal aspects of citizenship as a bundle of lived experience and state policies while concurrently, it theorizes such differentiated experiences by offering a unique category of citizens yet to be addressed in the existing literature.

Acknowledgments

My sincerest thanks to Reece Jones and Will Cecil for their comments on earlier versions of the paper. The phrase “showcase citizens” sparked during a lively conversation with Jacob Henry at the University of Hawaiʻi. I am indebted to my research assistant Morshed. I am forever grateful to the former enclave residents who welcomed me into their homes and lives. Finally, thanks to the anonymous reviewers for sharing their wisdom and constructive comments.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Md Azmeary Ferdoush

Md Azmeary Ferdoush is a postdoctoral researcher in the Karelian Institute at the University of Eastern Finland, Finland. He specializes in the study of borders, citizenship, state, sovereignty, and territory.

Notes

1. The schoolteachers under the MPO scheme receive a certain percentage of their salaries from the state. Not all private schools are covered by the MPO.

2. My use of the terms ‘sovereign’ and ‘state’ often overlaps in this paper, as drawing on other studies, I contend that the abstractness of sovereign power comes into being through the daily operations of numerous state apparatuses and actors. See (Ferdoush Citation2021a; Hansen Citation2001; Painter and Jeffrey Citation2009) for details.

3. In this context ‘sovereign’ refers to one ‘who possessed the power to let live or to make die in the former enclaves and supplanted the power with the administration of bodies and management of lives after their exchange’ (Ferdoush Citation2021a, 547).

4. Numerous national and international outlets covered the enclaves’ exchange both before and after it, which made and kept the issue a matter of interest to audiences not only in Bangladesh and India but across the world. Such interests drew attention from widely circulated outlets like the BBC, Bloomberg, Reuters, and the London School of Economics (LSE) blog, both before and after the exchange (Goethe Institute Citation2021; Hasan Citation2017; Mohan Citation2015; Quadir Citation2015; Santoshini Citation2016). Furthermore, the award-winning photographer Luke Duggleby covered the exchange in great length, which is publicly available on his website (see https://www.lukeduggleby.com/from-nomans-land-to-the-unknow for details).

5. Pseudonyms have been used for all respondents except the president of the Farmer’s Club, because there is no potential to compromise Ainal’s position in society. Verbal consent was sought from all the respondents and officials I interviewed to audio record them, and issues of anonymity and confidentiality were clearly explained to all of them following the IRB policies of the University of Hawaii at Manoa. While almost all the enclave residents and Bangladeshi citizens gave permission for audio recording, many state officials did not. I do not directly quote them in these cases but paraphrase them based on my fieldnotes. Furthermore, some officials wished to remain anonymous, while many gave permission for their names and designation to be used. However, I do not identify any of them in this paper. In deciding on the use of real names and pseudonyms, the utmost importance was given to the potential of harm of any kind, including the compromising of their position in their social and professional lives. Such decisions have been made drawing on IRB rules and the author’s experience and close familiarity with Bangladeshi society. I shed light on the issues of ethics and fieldwork dilemmas for the current research elsewhere at length (Ferdoush Citation2020, Citation2021b). Moreover, for a discussion of fieldwork challenges along the Bangladesh–India borders see (Hussain Citation2013; Cons Citation2014).

6. Fulbari in Bengali literally means home of flowers. The PM was comparing the former enclave residents with flowers.

References

- Agamben, G. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. New Jersey: Stanford University Press.

- Bashar, R. 2015. “Government to Do Everything for Welfare of Enclave Residents, Says PM Hasina.” https://bdnews24.com/bangladesh/2015/10/15/government-to-do-everything-for-welfare-of-enclave-residents-says-pm-hasina

- Berenschot, W., and G. van Klinken. 2018. “Informality and Citizenship: The Everyday State in Indonesia.” Citizenship Studies 22 (2): 95–111. doi:10.1080/13621025.2018.1445494.

- Butler, J. 2011. Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”. London: Routledge.

- Chatterjee, P. 2004. The Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most of the World. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Cons, J. 2014. “Field Dependencies: Mediation, Addiction and Anxious Fieldwork at the India-Bangladesh Border.” Ethnography 15 (3): 375–393. doi:10.1177/1466138114533457.

- Cons, J. 2016. Sensitive Space: Fragmented Territory at the India-Bangladesh Border. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Dhaka Tribune. 2015. “PM Intends to Visit Enclaves.” Dhaka Tribune. https://www.dhakatribune.com/uncategorized/2015/05/11/pm-intends-to-visit-enclaves

- Ding, I. 2020. “Performative Governance.” World Politics 72 (4): 525–556. doi:10.1017/S0043887120000131.

- Dunn, K. C. 2010. “There Is No Such Thing as the State: Discourse, Effect and Performativity.” Forum for Development Studies 37 (1): 79–92. Routledge 10.1080/08039410903558285.

- Ferdoush, M. A. 2014. “Rethinking Border Crossing Narratives: A Comparison between Bangladesh-India Enclaves.” Journal of South Asian Studies 2 (2): 107–113.

- Ferdoush, M. A. 2019a. “Symbolic Spaces: Nationalism and Compromise in the Former Border Enclaves of Bangladesh and India.” Area 51 (4): 763–770. doi:10.1111/area.12539.

- Ferdoush, M. A. 2019b. “Acts of Belonging: The Choice of Citizenship in the Former Border Enclaves of Bangladesh and India.” Political Geography 70 (April): 83–91. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.01.015.

- Ferdoush, M. A. 2020. “Navigating the ‘Field’: Reflexivity,Uncertainties, and Negotiation along the Border of Bangladesh and India.” Ethnography 146613812093704. online first. doi:10.1177/1466138120937040.

- Ferdoush, M. A. 2021a. “Sovereign Atonement: (Non)citizenship, Territory, and State-Making in Post-Colonial South Asia.” Antipode 53 (2): 546–566. doi:10.1111/anti.12685.

- Ferdoush, M. A. 2021b. “To ‘Help’ or Not to ‘Help’ the Participant: A Global South Ethnographer’s Dilemma in the Global South.” Geoforum 124 (August): 75–78. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.06.004.

- Ferdoush, M. A. 2022. “Flexible Land: The State and Its Citizens’ Negotiation over Land Ownership.” Geoforum 130 (March): 46–58. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.02.003.

- Ferdoush, M. A., and R. Jones. 2018. “The Decision to Move: Post-Exchange Experiences in the Former Bangladesh-India Border Enclaves.” In Routledge Handbook of Asian Borderlands, edited by A. Horstmann, M. Saxer, and A. Rippa, 255–265. London: Routledge.

- Gaja, M., and S. M. Hughes. 2017. “Contested Spaces of Citizenship: Camps, Borders and Urban Encounters.” Citizenship Studies 21 (6): 625–639. doi:10.1080/13621025.2017.1341657.

- Goethe Institute. 2021. “Chhitmahal.” Accessed June 30. https://www.goethe.de/ins/in/en/sta/kol/pro/inm/cib.html

- Gupta, A. 2012. Red Tape: Bureaucracy, Structural Violence, and Poverty in India. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hansen, T. B. 1999. The Saffron Wave: Democracy and Hindu Nationalism in Modern India. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Hansen, T. B. 2001. Wages of Violence: Naming and Identity in Postcolonial Bombay. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Hasan, M. I. 2017. “Land Administration in Bangladesh: Problems and Analytical Approach to Solution.” International Journal of Law 3 (2): 44–49.

- Henderson, V. L. 2009. “Citizenship in the Line of Fire: Protective Accompaniment, Proxy Citizenship, and Pathways for Transnational Solidarity in Guatemala.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 99 (5): 969–976. doi:10.1080/00045600903253403.

- Hull, M. S. 2012. Government of Paper: The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan. Berkley, CA: University of California Press.

- Hussain, D. 2013. Boundaries Undermined: The Ruins of Progress on the Bangladesh/India Border. London: Hurst Publishers.

- Isin, E. F. 2009. “Citizenship in Flux: The Figure of the Activist Citizen.” Subjectivity 29 (1): 367–388. doi:10.1057/sub.2009.25.

- Isin, E. F., and G. M. Neilsen, edited by. 2008. “Theorizing Acts of Citizenship.” In Acts of Citizenship, 15–44. Zed Books: London.

- Jackson, M. September 15 2021. “Former IS Teenage Bride Shamima Begum Offers to Help Fight Terror in UK.” In BBC News, sec. UK. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-58573501

- Jones, R. 2009a. “Agents of Exception: Border Security and the Marginalization of Muslims in India.” Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space 27 (5): 879–897. doi:10.1068/d10108.

- Jones, R. 2009b. “Sovereignty and Statelessness in the Border Enclaves of India and Bangladesh.” Political Geography 28 (6): 373–381. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2009.09.006.

- Jones, R. 2010. “The Border Enclaves of India and Bangladesh: The Forgotten Lands.” In Borderlines and Borderlands: Political Oddities at the Edge of the Nation-State, edited by A. C. Diener and J. Hagen, 15–32. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Joppke, C. 2007. “Transformation of Citizenship: Status, Rights, Identity.” Citizenship Studies 11 (1): 37–48. doi:10.1080/13621020601099831.

- Kabeer, N. 2002. “Citizenship, Affiliation and Exclusion: Perspectives from the South.” IDS Bulletin 33 (2): 1–15. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2002.tb00021.x.

- Kabeer, N., ed. 2005. Inclusive Citizenship: Meanings and Expressions. London: Zed Books.

- Kingston, L. N. 2014. “Statelessness as a Lack of Functioning Citizenship.” Tilburg Law Review 19 (1–2): 127–135. Ubiquity Press 10.1163/22112596-01902013.

- Kingston, L. N. 2017. “Worthy of Rights: Statelessness as a Cause and Symptom of Marginalisation.” In Understanding Statelessness, edited by T. Bloom, K. Tonkiss, and P. Cole, 17–34. London, UK: Routledge.

- Kingston, L. N. 2019. Fully Human: Personhood, Citizens and Rights. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Koch, N. 2016. “Is Nationalism Just for Nationals? Civic Nationalism for Noncitizens and Celebrating National Day in Qatar and the UAE.” Political Geography 54: 43–53. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.09.006. September.

- Koch, N. 2020. “The Corporate Production of Nationalism.” Antipode 52 (1): 185–205. doi:10.1111/anti.12588.

- Krishna, S. 1994. “Cartographic Anxiety: Mapping the Body Politic in India.” Alternatives 19 (4): 507–521. doi:10.1177/030437549401900404.

- Lemanski, C. 2020. “Infrastructural Citizenship: The Everyday Citizenships of Adapting And/or Destroying Public Infrastructure in Cape Town, South Africa.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 45 (3): 589–605. doi:10.1111/tran.12370.

- Lister, R. 2007. “Inclusive Citizenship: Realizing the Potential.” Citizenship Studies 11 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1080/13621020601099856.

- Ludden, D. 2003. “Presidential Address: Maps in the Mind and the Mobility of Asia.” The Journal of Asian Studies 62 (4): 1057–1078. doi:10.2307/3591759.

- Martin, D. 2015. “From Spaces of Exception to ‘Campscapes’: Palestinian Refugee Camps and Informal Settlements in Beirut.” Political Geography 44 (January): 9–18. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.08.001.

- Mathur, N. 2016. Paper Tiger: Law, Bureaucracy and Developmental State in Himalayan India. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press.

- McCargo, D. 2011. “Informal Citizens: Graduated Citizenship in Southern Thailand.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 34 (5): 833–849. doi:10.1080/01419870.2010.537360.

- McEwan, C. 2005. “New Spaces of Citizenship? Rethinking Gendered Participation and Empowerment in South Africa.” Political Geography 24 (8): 969–991. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2005.05.001.

- Ministry of External Affairs. 2015a. “India and Bangladesh Land Boundary Agreement.” http://www.mea.gov.in/Uploads/PublicationDocs/24529_LBA_MEA_Booklet_final.pdf

- Ministry of External Affairs. 2015b. “Exchange of Enclaves between India and Bangladesh.” https://www.mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/26048/Exchange+of+enclaves+between+India+and+Bangladesh

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2016. “Remarks by Hon’ble Foreign Minister at the Inaugural Ceremony of the 7thBangladesh-India Friendship Dialogue, 4 March 2016, Hotel Sonargaon, Dhaka.” https://mofa.gov.bd/media/remarks-hon’ble-foreign-minister-inaugural-ceremony-7thbangladesh-india-friendship-dialogue-4

- Mohan, S. 2015. “The Enclave Exchange: Some Concerns.” Times of India Blog, October 17. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/from-the-fence/the-enclave-exchange-some-concerns/

- Ong, A. 1999. Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logic of Transnationality. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Painter, J., and A. Jeffrey. 2009. Political Geography. London: Sage publications.

- Quadir, S. 2015. “India, Bangladesh Sign Historic Land Boundary Agreement.” Reuters, June 6. sec. APAC. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bangladesh-india-enclaves-idUSKBN0OM0IZ20150606

- Rahman, A.-U., and S. Khan. October 14 2015a. “Bodel Gase Dasia Chhara (Dasiar Chhara Has Changed).” The Daily Prothom Alo.

- Rahman, A.-U., and S. Khan. October 16 2015b. “Ora Notun Ak Guchho Phul, Prodhan Montri Dasiar Chharai, Manusher Dhal (They are a New Bunch of Flowers, the PM in Dasiar Chhara, People Pour In).” The Daily Prothom Alo.

- Ramaswamy, S. 2008. “Maps, Mother/Goddesses, and Martyrdom in Modern India.” The Journal of Asian Studies 67 (3): 819–853. doi:10.1017/S0021911808001174.

- Redclift, V. 2011. “Subjectivity and Citizenship: Intersections of Space, Ethnicity and Identity among the Urdu-Speaking Minority in Bangladesh.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 12 (1): 25–42. doi:10.1007/s12134-010-0163-3.

- Redclift, V. 2013. “Abjects or Agents? Camps, Contests and the Creation of ‘Political Space’.” Citizenship Studies 17 (3–4): 308–321. doi:10.1080/13621025.2013.791534.

- Redclift, V. 2016. “Displacement, Integration and Identity in the Postcolonial World.” Identities 23 (2): 117–135. doi:10.1080/1070289X.2015.1008001.

- Samaddar, R. 1999. The Marginal Nation: Transborder Migration from Bangladesh to West Bengal. Dhaka: UPL.

- Santoshini, S. 2016. “Waiting for a Better Life on the India-Bangladesh Border.” Bloomberg.Com, January 15. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-01-15/on-the-india-bangladesh-border-enclaves-wait-for-a-better-life

- Scott, J. 1998. Seeing like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Conditions Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Shewly, H. J. 2013. “Abandoned Spaces and Bare Life in the Enclaves of the India–Bangladesh Border.” Political Geography 32 (January): 23–31. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.10.007.

- Staeheli, L. A. 2011. “Political Geography: Where’s Citizenship?” Progress in Human Geography 35 (3): 393–400. doi:10.1177/0309132510370671.

- Staeheli, L. A., P. Ehrkamp, H. Leitner, and C. R. Nagel. 2012. “Dreaming the Ordinary: Daily Life and the Complex Geographies of Citizenship.” Progress in Human Geography 36 (5): 628–644. doi:10.1177/0309132511435001.

- Staeheli, L. A., D. J. Marshall, and N. Maynard. 2016. “Circulations and the Entanglements of Citizenship Formation.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106 (2): 377–384. doi:10.1080/00045608.2015.1100063.

- Sur, M. 2021. Jungle Passports: Fences, Mobility, and Citizenship at the Northeast India-Bangladesh Border. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Tripp, C. 2018. “The State as an Always-Unfinished Performance: Improvisation and Performativity in the Face of Crisis.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 50 (2): 337–342. doi:10.1017/S0020743818000247.

- Turner, J. 2016. “(En)gendering the Political: Citizenship from Marginal Spaces.” Citizenship Studies 20 (2): 141–155. doi:10.1080/13621025.2015.1132569.

- van Schendel, W. 2002. “Stateless in South Asia: The Making of the India-Bangladesh Enclaves.” The Journal of Asian Studies 61 (1): 115–147. doi:10.2307/2700191.

- Weber, C. 1998. “Performative States.” Millennium 27 (1): 77–95. doi:10.1177/03058298980270011101.

- Whyte, B. R. 2002. Waiting for the Esquimo: An Historical and Documentary Study of the Cooch Behar Enclaves of India and Bangladesh. Melbourne, Australia: School of Anthropology, Geography and Environmental Science, University of Melbourne.

- Winichakul, T. 1994. Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of A Nation. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.