ABSTRACT

Digital platforms operating on a global scale (social media, commerce, services, e-government and e-management services) are increasingly critical means for communication, exchange, and daily life, even without a direct use of platforms or connected devices. Their growing ecosystem and locally specific variations increase possibilities for data collection and targeting specific user profiles. Work life has become increasingly dependent on platforms including, for example, Microsoft's power platform, Google cloud, or the Apple iOS system. But also within community services and urban development, platforms are increasingly forming a firm component that may be for submitting taxes, getting health services, reporting suspicious activities in the neighborhood, profiling a political campaign, monitoring energy performances, or providing new employment opportunities. We argue that these processes in fact describe a specific kind of urbanization that is driven and administered through the digital means of platform technologies. This process of platform urbanization imbues every aspect of the urban environment and has experienced an acceleration during the recent pandemic. This contribution introduces the concept of platform urbanization and investigates the implications on citizenship and its digital realm, followed by an attempt to expand its conception. To bolster our argument, we discuss the case of Singapore, where the monitoring and control of the virus spread expedited the nation’s digitization efforts and where platform corollaries of the pandemic were seamlessly incorporated into an increasingly digital urban environment. In what follows, the last section brings about a series of questions addressing an urban digital citizenship scenario within platform urbanization as a space of empowerment, inclusion and participation.

1. Introducing Platform Urbanization

The urban realm is increasingly defined by platform infrastructures shifting many modes of interaction and production, of urban governance and identity, to a virtual space (Kitchin Citation2014). Platform urbanization captures planetary phenomena and their various dimensions, creating heterogeneous conditions within and among national territories. It is creating in itself an uneven geography of power, access and capacities to partake in shaping this process by ‘[blurring] the lines between “makers” and “consumers” of digital content’ (Barns Citation2020, 37), on the one hand, and creating dependencies of users on the interest of producers on the other. The concept of platform urbanization seizes a new mode of spatial production that is increasingly defining the urban condition as a result. It also aims to contribute to an enriched vocabulary of urbanization processes that is needed to enable urban scholars to better understand empirically and theoretically the plethora of urbanization processes shaping the urban condition today (Schmid et al. Citation2017). It also changes the way people come together and interact, creating a multidimensional process that is affecting our everyday life and the way our urban environment is perceived and governed including the key actors behind.

Platform urbanization focuses on the processes that constitute the urban and urban life, instigated by platform infrastructures, which propel the digitization of our environment. Platforms, in our definition of platform urbanization, are the infrastructure by which a particular global process increasingly defines everyday life in a physical and spatial way. This includes digital platforms for social media, commerce, government services and work management and ranges from bespoke solutions to global platform ecosystems, such as Alphabet (Google), Microsoft and Meta Platforms (facebook). As such, they are also determining ways of defining the political scenario, capital accumulation, urban regulation, and financialization. More precisely, we refer to the ‘institutional logics of platforms in general by considering their technical processes as political technologies’ (Bratton Citation2015, 19).

1.1. Platform urbanization and platform urbanism

To capture the wide range of implications and their transformative capacities, this contribution looks beyond urban form and platforms as a new form of urbanism (Barns Citation2014) but at the related processes that are emerging as a result. Platform urbanism engages with the ‘many registers of urban life and experience that platforms act upon’ (Barns Citation2018), and focuses on capturing new kinds of spaces the digital is creating (Barns Citation2020). As such, platform urbanism serves as a fruitful inquiry for platform ecosystems and the changing role of data in meaning, significance, and application within cities (Barns Citation2020a). Platform urbanization on the other hand focuses on the process of urbanization, which defines new standards and protocols of interaction and exchange on a planetary scale, extending beyond the city. They are driven by data without any limitation to specific categories and not confined to specific types of settlement structures. Platform urbanization also changes the way we can express ourselves as individuals (from metoomvmt.org to tiktok.com), how we think of our urban environment (as an intermediator, as an offline version of an online experience), and what we can do to plan, manage, or predict its development (through building information, modeling platforms or digital twins). It also expedites the production and dissemination of information and knowledge as well as new learning experiences (by creating unexplored set of skills and cybernetic urban-systems, as Reijers et al. explore in this issue). We consider platform urbanization as one step in the continuous production of urban nature as a process of ‘social and bio-physical change in which new kinds of spaces are created and destroyed’ (Gandy Citation2005, 63) including technological networks that give sustenance to the modern city.

1.2. Platform urbanization and smart city narratives

The current discourse on cities that have incorporated platform technologies for entrepreneurial and regulatory purposes focuses largely on ‘the effects of ICT on urban form, processes and modes of living’ (Kitchin Citation2014, 1) as well as ‘new expectations of network flexibility, demand responsiveness, green growth, new services and connected communities’ (Luque-Ayala, McFarlane, and Marvin Citation2016). The subject of these discourses, which can be subsumed under the wide label of ‘smart cities’, largely focuses on the technological, governance and human resource dimensions of the urban (Meijer and Pedro Rodríguez Bolívar Citation2016). Neither, however, do they capture the increasingly pervasive and ubiquitous influence of platforms as a planetary process nor its implications on citizenship. Smart cities hinge on material infrastructures that have propelled the industry of smart technology producers, pursuing a technological solutionism that often dismisses the multilayered implications of their implementation (Calzada Citation2021; Kitchin Citation2015). They are embedded in ‘hyper-connected societies that enthusiastically embrace Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) as a key component of the infrastructure of modern cities’ (Calzada and Cobo Citation2015, 24). While the definition of smart cities initially focused on ‘(…) the potential of the city as a platform where people could interact and access city services in a range of ways’ (Calzada Citation2021, 45) it has increasingly been stretched to incorporate manifold definitions of smart cities that are contingent on technological components. Technology is then usually defined as a normatively neutral and strictly functional device, to be applied to several infrastructures, enabling smart grids, healthcare, transportation, mobility and logistics, and governance (Morozov and Bria Citation2018). From this viewpoint, a city can be considered smart when it has ‘integrated wireless communication platforms’, which enable the interconnection and sharing of information between ‘sensing and actuating devices (…) through a unified framework’ (Hashem et al. Citation2016, 750). This increasing relevance of information technologies for urban economies raises questions about the spatial dimension of knowledge and ICT technologies and the specific processes of urbanization that informational technologies have undergone (Shelton and Lodato Citation2019). Within that new spatial dimension, the emerging discourses on platform urbanization ‘captures the specificities of platform materialities beyond smart city formations’ (Leszczynski Citation2020, 190), and highlight the changing relationship between technology, capital, and cities (Sadowski Citation2020, 449).

In the context of smart cities, the participation of citizens is usually postulated as the ability to mobilise human capital, sufficient skills, access and usage to digital platforms (Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Citation2011). This understanding of participation suggests the ‘(…) imaginary of a citizen as a subject who is often submissive (if not obedient) and is active only in ways recognized by government policies and programmes’ (Isin and Ruppert Citation2020, 73). Furthermore, the concept of smart cities always captures a particular urban condition that is generated through technologies, rather than capturing a process of urban transformation. Latter is our aim with the introduction of platform urbanization. The concept aims at a holistic description of a process affecting the urban and its material and immaterial dimensions, including the regulatory and institutional sphere; the physical environment and modes in which it is produced; as well as social and political aspects defining citizenship.

1.3. Dimensions of platform urbanization

Our socio-political theorization of platform urbanization neither focuses on its modus operandi or physical constellation, nor its technical and specific structure. Rather, we are concerned with the planetary as well as geographically specific implications of platforms on our urban environment and citizenship in particular. To generate a productive exploration, we therefore suggest thinking about platforms as a capacity to drive and transform the political and social urban landscape that we will focus on in this contribution.

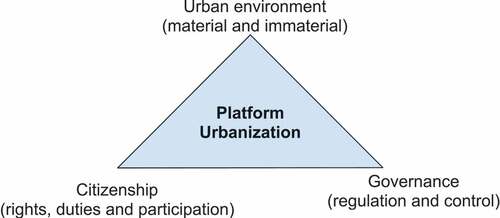

For the analysis of platform-driven urban processes, we focus on three dimensions deployed throughout the article and framing the Singapore case-study: firstly, the urban environment in its material and immaterial dimension; secondly, urban governance and means of regulation and control; and lastly citizenship and related rights, duties, practices and modes of participation (see ).

Urban Environment: Platform urbanization processes engender a new relationship between people and their urban environment by way of introducing various kinds of digital interfaces and sensors linking the two. Furthermore, they provide a new, digital urban realm for action as well as control. The digital urban realm and its relationship to the urban is not only one of acceleration and augmentation but also one of competition and contestation. The urban space is subsequently increasingly bereaved of some of its core functions that are shifting to the digital realm while others are being lost entirely.

Urban Governance: Platform urbanization is a conceptual tool to further a dialogue between technological, social, political and economic dimensions. It captures modes of policy making and implementation, urban planning models as well as urban life, which, together, have brought about a shift in citizenship practices. In a process of dematerialization, abstraction and disassociation, platform urbanization implies a form of governance that is introducing new techno-politics of data (Calzada Citation2021). As a result, the urban becomes a new techno-political arena where the individual is a site for data collection as well as a node of flows of information, knowledge and expertise (Foley and Miller Citation2020) and urban governance a matter of managing and policing administrative procedures (Swyngedouw Citation2019) as well as urban life by itself.

Citizenship: While citizens are often involved in providing responses or reactions to practical issues of platform infrastructures, they are, however, seldom included in the actual change of the underlying political rationale (implemented through platforms). The increasing relevance of platforms for the production of urban spaces therefore raises questions about the dissemination and exchange of knowledge (Bauriedl and Strüver Citation2020) and the specific processes of urbanization that platforms and their technologies are promoting (Shaw and Graham Citation2017). Individual skill sets are no longer unique but feed processes of algorithmic reorganization and augmentation of data aggregation. This entails a non-articulate form of exploitation of the individual value and, as a result, a ‘deprivation’ of individual skills. This also includes new capacities for individualized influence (Leszczynski Citation2020, 193) but at the same time, it is rendered by dispossession of individual voices, antagonistic subjectivation (Cuppini, Frapporti, and Pirone Citation2015), and restricted access and user capacities.

2. Platform urbanization and the pandemic accelerator

Platform urbanization has experienced a worldwide acceleration during the global pandemic starting in 2020 and the subsequent lockdown. During this pandemic, platform technologies were introduced in large numbers by national governments to monitor ‘safe distancing’ interaction in a variety of realms (work, commerce, education, culture, etc.), including people’s movement and the spread of the virus itself (Levy and Stewart Citation2021). In the realm of work, commerce and education in particular, platform services have exponentially grown, as, for example, the drastic increase of annual zoom meeting minutes from 79 billion in the second quarter of 2020 to 3.3 trillion in the third quarter of 2021 shows (https://backlinko.com/zoom-users), or the growth of e-commerce in 2021 (UNCTAD Citation2021). During their varying periods of lockdown, 190 countries have faced complete or partial closures of their physical educational institutions and as a result, more than 1.7 billion students have been affected by a shift to online teaching (https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/edutech/brief/lessons-for-education-during-covid-19-crisis). From an educational perspective, COVID-19 thus implies more than a disruption that needs to be addressed with digital learning models offered by platforms; it is also an opportunity to query and debate the relevance and appropriateness of their globalized pedagogical model (Adeela and Ayaz Naseem Citation2021; Fischman and Estellés Citation2020). In addition, numerous new platforms have become available to track and report one’s own health condition or vaccination status. Depending on the regionally specific IT infrastructures in place, such platforms had to be developed from scratch, a process that was often accompanied with vocal public debates around concerns of privacy and a growing state surveillance (Storeng and de Bengy Puyvallée Citation2021).

2.1. Controlling the urban environment

Authorities at an urban, regional, national or supranational levels have adopted ways to control, surveille, and monitor through platforms and IT infrastructures. This has mobilized questions regarding inequality, data sovereignty, and the authorization of policy making (Katapally Citation2020). These practices of platforms-driven surveillance vary from particular ways of citizenship practice (as elaborated by Reijers et al. in this issue for the case of China) to inflating processes of digitized administrative services to map individual access and ways of usage (frequency, timing, scopes). In other cases, the same surveillance practices were created as an expansion of existing platform ecosystems, leveraging widespread digital literacy and compliance with data transparency. The latter is the case for Singapore, where necessary means to allow for a safe distancing interaction and monitoring of health conditions was swiftly implemented at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020.

The relation between the global pandemic and its implications on the urban realm reflects, in fact, the close entanglement of urban transformation and urban health (Gandy Citation2004). The modern city around the mid-19th century in Europe was the result of epidemiological advances and the necessary engineering responses to creating a healthy urban environment. Efforts to ensure an urban environment that allows a concentration of people to live and interact without compromising human health has historically always been closely tied to physical urban transformation, as we can see from the restructuring of Paris, London or Berlin in the second half of the 19th century. These urban restructuring processes served as means to maintain and/or control urban health with ‘combined processes of political-ecological transformation and socio-cultural reconstruction’ (Swyngedouw Citation2005, 22).

In light of this recent accelerated expansion of platform urbanization and a growing dependence on its infrastructures that perform extraction and execution operations (Zuboff Citation2019) we argue, that these processes of urban (re-)production demand a thorough investigation and understanding of their contingencies and corollaries in particular with regards to citizenship. With the introduction of platform urbanization we aim to address its growing influence on the nature, structure and production of the city and the practice of citizenship and capture its multidimensionality as well as pervasive character affecting every possible territory, and individual.

2.2. The techno-political rise

Regarding its territorial dimension, platform urbanization advances regardless of the existence of the nation-state, as many of its infrastructures extend seamlessly beyond any boundaries on the ground. More so, and as elaborated by Calzada as well as Bustard and Calzada in this issue, it propels us to consider a rescaling of the nation-state entity in the context of new citizenship regimes expedited through digitization and called for by new possibilities for democratic accountability. Processes of platform urbanization actuate and consolidate networks of global flows, extending conveniences of communication and mobility but also of traces left. Platform urbanization also coincides and enables a true techno-political scenario. Within such a techno-political scenario, political practice becomes a matter of governance, managing and policing administrative procedures (Swyngedouw Citation2019), a phenomenon that has become particularly eminent during the recent pandemic. Further, the proliferation of platforms, of new modes of urban production, and the re-conceptualization of political, economic and social interaction reifies a techno-political framework (Calzada Citation2021) which compels to revisit the concept of citizenship and to extend it (Hanakata and Bignami Citation2021). This requires a new theoretical approach to include on one hand a new citizenship taxonomy (see Calzada; Reijers et al.; Bustard & Calzada in this issue) and on other hand a conceptual grounding (see Kylasam Iyer & Kuriakose; Antenucci & Tomasello in this issue) of the heterogeneous regimes of urban digital citizenship. The idea of a techno-political scenario is particularly appropriated in the contexts of the urban environment impacted by COVID-19, where platformization processes, and technology in a wider sense, constitute, substantiate, and enact political aims, repositioning the city and opening a discussion about urban techno-politics (Foley and Miller Citation2020). Such a techno-political environment uncovers relationships that are often hidden behind complex arrangements of platform infrastructure, actors and organizations (see Calzada in this issue). This development, however, is not determined by the technology itself, but by those who create, deploy and control its use. While platforms provide the structures that enable and connect goods and services (Barns Citation2018; Leszczynski Citation2020), their application requires specialized knowledge and access to resources. A significant trait characterizing processes of platform urbanization therefore, is a centralized mode of control and the rapid development of algorithmic driven management in urban environments that increased at the end of the second decade of the 21st century (Huws Citation2017). Despite the opportunities for technology cooptation as well as platform-enabled co-creation, and a certain liberation of participation through open sourcing of data and tools, impact at a large scale remains dependent on access to resources and the capacities to obtain and direct data as well as users. A centralized control is also dominant in many smart city projects (Hemment and Townsend Citation2013), conceived as a ‘top-down, master planned vision shaped around the needs of suppliers rather than the needs of citizens’ (Calzada and Cobo Citation2015, 30) and also discussed as attempts of ‘smart urbanism’ (Sadowski and Bendor Citation2019; Wiig and Wyly Citation2016). This can be illustrated with recent greenfield developments which have been called out as the new platform city: major examples include the Pungol Digital District in Singapore, by JTC; Toronto Tomorrow in Canada, by Alphabet’s Sidewalk Lab (project cancelled); Woven City in Japan, by Toyota; NEOM in Saudi Arabia, by NEOM Company; Dholera in India, by a large conglomerate of public and private stakeholders. All these projects are relying on customized or all-in-one offered solutions by industry partners, such as Horizon Digital Platform (Huawei); Future X Cities Solutions (Nokia); or entirely virtual, platform-based projects such as Zuckerberg (Facebook). All of them are driven by or in collaboration with major digital market actors, and they provide smart infrastructures that are promoted as neutral facilitators for a more efficient living (Leszczynski Citation2020, 192). They focus on pragmatic and functional aspects of a top-down techno-utopia, such as the one of the sharing economy (Džankić Citation2018), and less on the social and political consequences including questions of citizenship, labour, mobility and the overarching techno-political framework that are all, however, an integral part of platform urbanization.

The following section explores the case of Singapore as a site for deeply entrenched and pervasive platform practices considering the recent pandemic. Drawing from that case study, we will investigate the implications on citizenship and the need to expand its contemporary understanding.

3. The changing digital urban landscape of Singapore

Singapore is a 720 square kilometer large island and city state with 5.7 million inhabitants. With that, it has one of the world’s highest population densities (The Straits Times Citation2018) and it has increased its population size since its independence 1965 by more than 300%, with every square meter of its terrestrial and maritime territory urbanized. It experienced a GDP growth of $517 per capita in 1965 to $65,641 in 2019 (The World Bank Citation2021) with an economy largely based on export of electronics, oil refining and financial services (The Commonwealth.org Citationn.d.). Singapore presents an example where the government has implemented very aggressive and effective measures in the attempt to fight the spread of COVID-19 (Abdullah and Kim Citation2020; Das and Zhang Citation2021). It built its expertise on experiences over the past decades with previous pandemics in the region, such as the SARS outbreak in 2003 or the H1N1 in 2009 but also in light of its particular vulnerability with a highly globally connected population and its function as an international exchange and trading hub. Its response strategy is embedded in a ‘unique geographical, technological and policy landscape’ (Chang and Das Citation2020) which has been established since its independence. Today, Singapore ranks among the countries with the highest percentage of households with internet access with 91% after the Republic of Korea and Japan (The World Bank Citation2016) and it has the highest fixed broadband speed in a global comparison (Speedtest Citation2019).

3.1. Singapore´s response during the pandemic

In its response to the pandemic, the Singapore Government deployed various technological means and services ranging from a nationwide, interlinked health status monitoring system of every citizen, to contact tracing apps. This approach has to be situated in the context of government-driven digitization efforts since the 1980s and the continuous fostering of knowledge and information in an otherwise resource-deprived country. Singapore released its first National Computerization Masterplan in 1981 and declared its aim to become an ‘intelligent island’ in 1992. Today, the government continues to pursue this agenda under the Smart Nation initiative that was established in 2014 and aims at improving people’s lives by creating more opportunities through ICT (Lee Citation2014). Since 2010, the government has made particular efforts to foster and encourage technology start-ups to sustain the nationwide platform-driven industry by providing seed funding and special mentoring programs (Chua Citation2019). More importantly, however, government officials started to call for a more aggressive, techno-entrepreneurial attitude among the younger generation in order not to fall under the wheels of the technological disruption taking place but be the one leading this shift (Lee Citation2016). This has created new ‘national sociotechnical imaginaries’ (Jasanoff and Kim Citation2009, 120) and a portrait of Singapore as a place ‘thriving by creating newer, more technologically innovative and hence, more commercially profitable enterprises’ (Chua Citation2019, 532). It also includes a redefinition of citizenship in terms of an identity from a hard working, skilled and obedient worker to a tech savvy techno-entrepreneur, contributing to Singapore’s global success narrative (Quah Citation2018) in this time and age.

In order to further develop the nation’s digitization and platform ecosystem, the Singapore Government has created a broad network of agencies, private companies and funding schemes. Supporting the Smart Nation initiative, research institutions (including the University of Singapore, the Nanyang Technological University and A*STAR, the government” Agency for Science, Technology and Research) form tight collaborations with technoparks hosting startup clusters (Chang and Das Citation2020) as well as other start-up clusters directly hosted by the government’s agency for industrial estates, the JTC Corporation. To fund the various platform-related efforts, SG Innovate, a private company founded in 2017 and owned by the Singapore Government to support technological innovation and start-ups, set aside US$250 Million in 2020 over three years for tech focused companies alone (SG Innovate Citation2020). Another program coined as ‘SMEs Go Digital’ aims to help SMEs specifically to use ‘digital technologies and build stronger digital capabilities to seize growth opportunities in the digital economy’ (Infocomm Media Development Authority Citation2021). This also includes the growing number of e-commerce platforms on the island. To illustrate this shift, we may look at the case of food delivery services in Singapore for which an increasing demand was registered since the start of the pandemic in 2020. Street food stalls and eating outside forms an important part of everyday life in Singapore (Henderson et al. Citation2012). The 5943 government licensed food stalls (Data.gov.sg Citation2021) form an important element in the urban landscape and central space for social gathering and exchange. The closure of these facilities during lockdown and people being bound to home drastically increased the demand for food delivery by 35.7% in 2020 (Statistica Citation2020). Enabling these hawker stalls and other F&B services to go online was part of the SME support program by the local government through e-commerce subsidy schemes (Tjendro Citation2021). Furthermore, Singapore Enterprise, a government statutory board to support SMEs, is subsidizing food delivery platforms, such as Grab Food, Deliveroo and FoodPanda to reduce additional costs particularly for smaller establishments (Tjendro Citation2021). As a corollary, gathering places for eating and central places of congregation have become deserted and fenced off. Scenes of zoning could be witnessed in other areas of the city, where the size of groups and the number of total people allowed was always strictly monitored through the digital check-in station, placed at the entrance of every eatery, shop or office, which demanded visitors to check in via their smartphones and the government’s digital passport app in the beginning and since May 2021 the compulsory TraceTogether app, the world’s first COVID-19 contact tracing application (Levy and Stewart Citation2021). The Bluetooth-based app developed by the Government Technology Agency is also automatically informed of people’s vaccination status from the Ministry of Health and shows any recent COVID-19 test results, information that every visitor is requested to provide upon entering any mall, food and beverage establishments.

Together, the various initiatives and tools present a very comprehensive and targeted effort towards the clear goal of sustaining Singapore’s urban economy and controlling the spread of COVID-19. The welter of different relevant statutory boards and government agencies in charge underpin the government’s central role in directing, monitoring, and funding this process. It presents Singapore as an example of pervasive, government-led platformization efforts that has been gradually built up providing the necessary infrastructures for a pandemic response already in place. In its continuous struggle for economic survival given its limited size and resources and with that its efforts to wield power over its people – and platform users – the Singapore government has been extremely visionary in introducing a socio-technical and techno-political imaginary for the nation and its narrative, determining modes of urban production as well as a specific understanding of urban digital citizenship.

3.2. An advanced platform urbanization scenario

Singapore’s efforts in response to the pandemic and the authoritarian practices with which the government was able to impose the necessary platform infrastructures, as well as a general data obedience among Singapore residents makes Singapore a territory of highly advanced platform urbanization and digital citizenship. Singapore epitomizes a state of platform urbanization that is far ahead in a planetary comparison. While some of these exceptional circumstances pose certain limitations on taking Singapore as a model (Christiaanse, Gasco, and Hanakata Citation2019), and/or deriving from its case more broadly applicable insights into modes that enable platform urbanization to progress and the ways it is conceded by citizens, it provides a glimpse of possible scenarios of future urban conditions elsewhere.

Within the context of a politically censorious and highly regulated society (Lee Citation2010) and in a space where digital management, communication and control is so pervasive, the question of digital literacy and access, however, becomes even more critical. Particularly among low-income households, differently abled, and senior citizens, digital literacy remains an issue and its shortcomings have been aggravated during the pandemic when working from home and home based learning became the default. Digital literacy and access to necessary devices became a decisive factor that ultimately increased the digital divide on the island (Ong Citation2020). With that, the pandemic has exposed the cracks and fault lines caused by perennial issues like inequality and equity in relation to access to technology in Singapore. These need to be urgently addressed in order to keep up with the rapidly expanding process of platform urbanization and the push towards a smart nation.Singapore, being infused by a ‘platform-based infrastructure and economy’ (Leong and Lee Citation2021), presents an interesting case study to investigate the pervasiveness of platform urbanization penetrating the realm of urban governance and control as much as everyday practices in an interconnected way. It illustrates central aspects of a techno-political scenario, with a governmentality that is highly effective and efficient in the way it is managing its subjects through platform infrastructures. It also allows one to better understand the kinds of urban citizenship that are the prerequisite and or result of platform urbanization processes, and the unevenness, with which it is unfolding over any socio-economic dimension of the urban.

4. Implications on citizenship

The concept of platform urbanization, as outlined in section 1 and 2, is based on an understanding of the urban as a dynamic, material and immaterial space where the pervasive use of platforms influences the modes of production of the urban itself. The making of the urban can therefore be described as a techno-political process (Calzada Citation2021; Foley and Miller Citation2020), which requires a closer look to understand the peculiar linkages between citizenship and technology (Dumbrava Citation2017). In this process, platforms are becoming a new ‘boundary condition’ for citizenship and space (beside and beyond the nation-state) in a techno-political condition, within which the individual and collectivity must re-learn to position themselves (see Calzada in this issue). This techno-political process merges digital and political, personal and collective arenas, and with that defines the way in which platforms infuse and unfold within the urban. Grasping this process also requires an understanding of how citizenship is being continuously re‐organized by platforms in urban spaces: through a complex interplay of socio-political variables that shape offline and online practices, including distortions of political representations (Milan Citation2018). In effect, a distinction between online space and platform interaction and physical offline space and human interaction continues to exist (Isin and Ruppert Citation2020). The line between the two, however, remains dynamic. To capture this line requires delving into the essence and modes of production, control, use and effects of data, softwares (including artificial intelligence), digital processes (for example, cloud computing or blockchain), hardware, and digital infrastructures.

The case of Singapore allows to substantiate the theorization of platform urbanization, since this city-state embodies both a pandemic citizenship scenario (Calzada in this issue) and an example of governance aimed at a truly platform-driven urban production with a techno-optimistic understanding of digital citizens. Singapore corroborates a vision of the urban where – facilitated by the local government and through the power and control over data – platforms are able to enter cities’ ‘control rooms’ (Söderström and Mermet Citation2020). Even before the pandemic, Singapore envisioned a city-state with advanced digital infrastructure for communication and service provision that was accepted and supported by an educated and technologically savvy workforce and urban dwellers.

As the case of Singapore elucidates, the city is a techno-political environment of platform urbanization where various layers and actors interplay within a territory of urban digital citizenship. In the case of nation-states creating and controlling platform ecosystems, their incentives sometimes clash with global tech market players that design, produce, sell and profit from platforms. On the one hand, nation-states in some cases, try to support and exploit market players, since technological development is also a matter of political choices and consensus (Cardullo Citation2021). Platform providers, on the other hand, competing much alike nation-states, often demand national support and protection, in spite of their global-scale operations and their substantial detachment from nationally bound rules and norms. Subsequently, there are many intersections between nation-states and platform providers in the realm of politics, economy and technology. These intersections also highlight the necessity to find an adequate space (both material and immaterial) within the urban realm ‘able to exploit the opportunities or cope with the fallout of tectonic movements and frictions’ (Minas Citation2020, 66). In this complex techno-political scenario, there is a particular kind of political leverage inherent (including the power to decide on data, coalesce rule-making, etc.) that is unattainable for individual citizens. Benjamin Bratton´s (Citation2015) notion of ‘platform sovereignty’ corroborates the emergence of techno-political environments. His notion is a particularly influential instance of this trend, and substantiates our viewpoint by investigating platforms from a geopolitical angle. Bratton suggests that platforms not only engender a political scenario infused by technological layers, but he also observes that platforms themselves are gradually becoming actors in this new environment claiming agency and taking political actions that have consequences. Within such a techno-political scenario, citizenship remains a dynamic parameter and to grasp it requires a broader and more complex political framework. Such a framework rests on social rights and redistribution of urban resources (Cardullo Citation2021). In fact, if we simply refer to techno-political ecosystems as digital platforms, we lose sight of a complex situation. As platforms leverage artificial intelligent (AI) applications to improve their actions and ecosystem, they further fortify the functional superiority of their services. This makes platforms no longer mere infrastructures for online shopping, or contact tracing to limit pandemic spread but it makes them politically powerful tools. These are yielded by platform companies that emerge with a kind of ‘functional sovereignty’ (Pasquale Citation2017), which may indeed threaten the logic of territorial sovereignty associated with that of the nation-state.

In such a multifaceted and intricate present, where analog political processes are crossed and inflated by digital politics, a certain level of ‘sovereignty’ on both sides seems necessary to foster democracy, equality and a balance in (digital) citizenship. In other terms, we are confronted with a scenario where institutional sovereignty at multiple levels (urban, nation-states and supra-national), big-tech companies, and economic forces deeply affect and continuously challenge the notion of citizenship. This is due to an imbalance:, on the one hand, organizers and providers of this scenario are private oligopolies, which are built on technical and restricted know-how, creating growth as well as deprivation, wealth and exploitation. On the other hand, users and supposedly digital citizens are often ill-informed regarding the platform ecosystem they navigate through on a daily basis, voluntarily or not. Imbalances like this one are inherent in all ‘technological turns’ (Tomasello Citation2022) and present a profound and game-changing technological step. This is the case despite the fact that citizens are dependent on technologies to participate in today’s digital society, and require access to digital information to make informed social, political, cultural, and economic decisions (Oyedemi Citation2015). In other words, online spaces should be conceived as digitally mediated inter-relational spaces where citizens perform political and social co-constructed citizenship practices (Quodling Citation2016). The case of Singapore shows, however, that this does not come by itself. Such practices require a deliberate intervention, activation, and participation from the bottom. The role of the pandemic, in Singapore’s case, plays a critical role, since it furthered platform urbanization processes away from such practices of co-construction.

4.1. Citizenship framed in the urban digital environment

The current techno-political scenario of platform urbanization has disrupted conventional politics based on nation-states and, further, is creating new kinds of politics without precedence. Platforms have given rise to new spaces and subjects of politics, highlighting how ‘historical’ assemblages of territory, authority and rights linked to nation-states have been re-settled and re-organized (Sassen Citation2006, Citation2016). Furthermore, these re-assemblages have created the need to extend the concept of citizenship (Hanakata and Bignami Citation2021) in three main directions: (a) regarding inclusion of many politically, linguistically, technologically and culturally different forms of interaction; (b) in consideration of different typologies of citizen communities: urban, international and, increasingly, platform based; and c) with respect to a validity beyond the nation-state as a physical anchorage and beyond a formal conceptual contour. These three directions are also derived from the fact that urban citizenship started to be discussed more vigorously at the beginning of the 21st Century, when the nation-state was no longer sufficient to address and collocate the notion of citizenship (Sassen Citation2002; Bauböck and Orgad Citation2020). The urban environment seems a suitable locus where additional forms of citizenship can be co-constructed, negotiated and set apart from a collectivity aiming towards a ‘performative’ interpretation of citizenship (Isin Citation2017). This urban citizenship reflects the political capacity and right to shape the city in presence of different regimes of citizenship (Kylasam Iyer Citation2019), including the digital. This, however, also implies the need for a further enrichment of the citizenship concept, but also poses the question on how a socio-political debate is able to include citizens and their capacity to co-operate, to participate in the making of the urban, and to mark a presence (Ennaji et al. Citation2021) both offline and online. In light of the above depicted urban citizenship, what is now at stake are forms of political mediation that are necessary to participate in a platform-driven urban environment. This is not a technical matter, but rather a political and governmental concern, since it pertains to finding a space that allows both, online and offline urban space to conjoin. In these terms, online spaces can be thought of as platform-mediated interrelational spaces where citizens co-create and perform citizenship practices (Atif and Chou Citation2018). The digital, therefore, may be conceptualized as a further extension of platform-mediated citizenship.

Platform urbanization processes, as mentioned above, are characterized by disjunctions between a formal notion of citizenship in terms of deservingness and the practical realities of how citizenship is embodied. Such disjunctions create instances in which trade-offs must be accepted (e.g. less freedom and more security; less responsibility and more perceived comfort, etc.) which often result in comfortable but exclusive forms of citizenship (limited for some groups, for some neighborhoods, for some surveilled behaviors, for some economic conditions, for some markets, for some services, for some forms of participations, etc.). COVID-19 has further aggravated such disjunctions. As a corollary already existing forms of ‘differential inclusion’ (Mezzadra and Neilson Citation2012) are increased, and new ones are being created, including new rules and bans that are generating shifting borders that offer latitudes for the few and restrictions for the many (Shachar Citation2020). Such an unbalanced techno-political scenario deeply affects urban citizenship, where an essential role is played by the single citizen as the nexus between individual and collectivity. Such nexus needs to be defined at the urban level, since it postulates a practical ground of fruition (Hanakata and Bignami Citation2021).

4.2. Evidence from Singapore on urban (digital) citizenship

Ever since the beginning of the pandemic, platform-driven urban production has been experiencing a significant increase in intensity and expansion: platforms have not only been facilitating social and economic life in times of physical contact restrictions but have resignified urban governance by creating additional political relations among people, institutions and global economic flows. The social and political narrative of a ‘techno-entrepreneurialism’ like in Singapore is indicative of governments’ efforts to promote tech business experimentalism (Laurent et al. Citation2021). Such top-down efforts are in this specific case modifying established notions of citizenship and nationhood (Chua Citation2019), and are penetrating almost every aspect of urban politics. The citizenry of Singapore is now imagined in a way that presupposes a different kind of self-understanding and relationship among citizens. The new narrative of national survival demands citizens to regard one another less as fellow bearers of a single socio-economic endeavour but as disparate and contending business ventures (Chua Citation2019). This makes an imbalance in the process of platform urbanization between organizers and providers and supposed digital citizens evident in Singapore. The persistence of a differentiation and separation between online and offline seems worthless in claiming political, social, digital, or data justice in Singapore, since citizens act through platforms, and create a continuous space of action that should be co-constructed in a cooperative way. But the conception of a digital savvy citizen can thus be seen to not only promote and encourage innovation but also to reimagine the urban realm. It calls on citizens to understand Singapore as a different kind of social, political and economic entity, which institutes a different kind of relation among its citizens. Instead of seeing the urban as a collectivity, whose members are bound together by their common investment in a single endeavour, this urban citizenship regime asks citizens to adopt a more individualistic conception of their efforts and outcomes. It retracts the collectivist promise that the activity of the individual citizen will be rewarded by the improved well-being of the urban realm as a whole and replaces it with the vision of citizens who are continuously engaged in their own, disparate business ventures, and whose ‘levels of wealth and well-being are thus continuously rising above and falling below one another’s’ (Chua Citation2019:541).

The case of Singapore therefore demonstrates the challenges to define a space for digital citizenship that allows for a co-creation in light of the ubiquitous presence of platforms, both online and offline. As such, it illustrates how the concentrated urban condition (opposed to extended urban territories) precedes a global monoculture with platformized citizens. The border between the physical and the digital in this urban scenario is blurred. Digital citizenship, no longer a link between political and social dimensions, is situated in a material and immaterial space. Such a space slowly but steadily tends to mutate into a technological and political development, which blurs the meaning of citizenship, and the significance of its co-construction and participation. The spread of platforms accelerated by the pandemic has further challenged a sense of collectivity in Singapore by replacing physical gathering places for a culturally diverse community that is based on shared norms and interests located in digitally mediated spaces. As platforms are opening up new spaces for citizenship, new ways of being and enacting citizenship have been made possible. However, Singapore demonstrates that differentiating digital citizenship from citizenship is questionable, since online digital spaces are anchored in offline material environments that are mediated through platforms and digital technologies (McCosker, Vivienne, and Johns Citation2016). This contribution has investigated the link between the urban environment and governance by broaching (digital) citizenship issues. The concept of platform urbanization focuses on the process that emerges through this particular juxtaposition and emphasizes the complex standing of citizens in a digital and political space. It addresses the changing modes of production of urban space and an extended definition of citizenship. They are the results of ubiquitous platform infrastructures, a growing regulation of collective action, communication and exchange through platforms, accelerated by COVID-19, and an outdated notion of citizenship framed only by a nation-state paradigm. It is worthwhile stressing that the aim of this contribution is less to investigate the operational modes of platform infrastructures, their formation and defining characters. Rather, we aim to examine the multilayered implications of platform urbanization on the urban realm and digital citizenship.

Moving forward, we believe that the conception of platform urbanization theorized as a process, in dialogue with concepts like smart city and platform urbanism in particular, can facilitate an understanding of the urban as more than an intermediator of user requests, data collection and provision. It can also further an understanding of the urban as a site of continuous transformation, collaboration and co-construction, and as a space in which urban society is more than the result of a nation-state’s socio-technical imaginaries. Crafted by capacitated and foresightful governments, platforms, firstly, need to be leveraged on as skill-enabler rather than abstract structures that dispossess the individual of skills. Considering digital citizenship not just from a technological angle but as a complex assemblage emphasizes again the pronounced political dimension of platform urbanization. Digital citizenship means enabling cooperation and co-construction of urban material and immaterial space, while fostering technical and digital literacy. The latter is necessary to avoid becoming a casualty of technological disruption but partaking in, and co-directing the shift that is taking place (Bignami and Hanakata Citation2022). This postulates a platform urbanization process that is informed and driven by the aim of civic value generation, not just in the interest of urban citizens, but in the interest of a sustainable and lasting transformation of our urban environment. This is a complex endeavor that demands more than optimized algorithms but a comprehensive approach including new modes of governance, and an extended conception of citizenship, succinctly captured by Kitchin when he claims that ‘technologies need to be complemented with a range of other instruments, policies and practices that are sensitive to the diverse ways in which cities are structured’ (2014:10).

Secondly, we need to ensure that platform urbanization also allows for what Calzada and Cobo refer to as ‘unplugging’ in regard to the smart city paradigm, notably, a corrective from the corporate, top-down direction of the smart city mainstream in favor of a transition towards the critical use of digital technologies enabling dimensions that can contribute to ‘(…) deconstruct our understanding of a smart city (…)’ (2021:17) in favor of a more democratic form of citizenship.

Thirdly, by bringing the content of a ‘new’ urban citizenship scenario to the centre of concern, we try to avoid a deterministic and techno-optimistic viewpoint of platforms and the conception of citizens as passive data subjects. Instead, we attend to how political subjectivities are always acting in relation to techno-political arrangements and technological urban infrastructures. We also shun libertarian analyses of platforms and their positivist assertions of sovereign subjects. We believe, however, that a focus on the capacities of participating, interacting and performing citizenship (Isin Citation2017) in the context of platform urbanization, rather than on how we are being controlled and potentially deprived by it, opens up a productive way forward in leveraging inherent possibilities. We contend that if we shift our focus from how we are being ‘controlled’ to the complexities of participating, interacting and performing citizenship acts (Isin Citation2017) by foregrounding citizen subjects not in isolation but in relation to the arrangements of which they are a part of, we can identify paths of being not just obedient digital citizens but also ‘subversive’ (Isin and Ruppert Citation2020).

Fourth, with this contribution, we also intended to respond to Ananya Roy’s call (Roy Citation2009, 820) noting that ‘it is time to blast open theoretical geographies, to produce a new set of concepts in the crucible of a new repertoire of cities’, we introduce platform urbanization in the hope to contribute to a global and at the same time more differentiated vocabulary of urbanization (Schmid et al. Citation2017). The conceptual introduction of platform urbanization aims to contribute to a more nuanced vocabulary of planetary urbanization (Schmid and Brenner Citation2011; Brenner Citation2018) by focusing on one particular aspect in which urbanization progresses. We hope this is understood as an invitation to debate and further an exploration in light of a highly dynamic urban condition.

Lastly, the concept of platform urbanization shows the ambivalence in the tension between the historical situation and embodiment of platforms’ attractive power as an immaterial political arena on the one hand, and its openness to be co-constructed on the other hand. This ambivalence emerges with new forms of polarization between authentic and inauthentic forms of being-together across and beyond physical boundaries and legal fixations. Polarizations between individual and collective spaces of action are being instrumentalized for political and economic interests. Considering the internet as a truly ‘global institution’ (Mathiason Citation2008), platforms are operative tools and offer reproductive approaches to access to power. Simultaneously, they enable knowledge production, which, in platform urbanization processes is constituted through the datafication of actions (Isin and Ruppert Citation2020) and the making of both data subjects and people as a materialization of data. The result is not always some kind of apparent freedom in the platform world but different kinds of platform warfare. Using the concept of citizenship based on its ‘modern’ definition in the physical world and translating it into the context of platform environments might lead to new elements of digital citizenship (see Antenucci and Tomasello in this issue), but it also bears the risk of creating a homogenized techno-political society. We hope to contribute to an understanding of what it might mean to speak of an augmented urban experience (see Reijers et al.; Kylasam Iyer & Kuriakose in this issue), of digital citizenship regimes in times of post-pandemic (see Calzada in this issue), and platform urbanization for that matter, and what these concepts entail for extant discussions of situated cities and citizenship alike.

Acknowledgement/Funding

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest concerning authorship and/or publication of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Filippo Bignami

Naomi C. Hanakata is an Assistant Professor for Architecture and Urban Design at the College of Design and Engineering at the National University of Singapore. She is also Co-Founder and consultant of HANAKATA, a research and planning practice based in Singapore.

Her work focuses on the research and development of adaptive planning strategies to deal with uncertainties and dynamic urban futures in urban development and planning. Addressing challenges of planetary urbanization, decarbonization, decentralization of resources and digitalization in planning practice are central in her work towards sustainable and equitable urban futures. She has practiced in Zurich, Tokyo, New York and Singapore as planner and consultant. She has taught at Rice University and ETH Zurich and was educated at ETH, Tokyo University and LSE, and holds a Ph.D. from ETH Zurich.

Filippo Bignami holds a PhD in Political and Social Sciences. He is a senior researcher and lecturer at the University of Applied Sciences of Southern Switzerland, Department of Economics, Health and Social Sciences (SUPSI-DEASS), LUCI (Labour, Urbanscape and Citizenship) research area. Among many scientific appointments, he has been external scientific consultant for UN-ILO International Labour Organization and project visiting professor at the Asia-Europe Institute, State University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. His main scientific interest and expertise is in citizenship social and political theories and applied studies on citizenship policies and education.

References

- Abdullah, W. J., and S. Kim. 2020. “Singapore’s Responses to the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Critical Assessment.” The American Review of Public Administration 50 (6–7): 770–776. doi:10.1177/0275074020942454.

- Adeela, A.-A., and M. Ayaz Naseem. 2021. “Politics of Citizenship during the COVID-19 Pandemic: What Can Educators Do?” Journal of International Humanitarian Action 6 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/s41018-020-00089-x.

- Atif, Y., and C. Chou. 2018. “Digital Citizenship: Innovations in Education, Practice, and Pedagogy.” Journal of Educational Technology & Society 21 (1): 152–154.

- Barns, S. 2014. “Platform Urbanism: The Emerging Politics of Open Data for Urban Management.” in American Association of Geographers Annual Conference, Tampa, FL. Tampa, FL.

- Barns, S. 2018. “Platform Urbanism Rejoinder: Why Now? What Now?” Mediapolis. Retrieved 18 November 2020 https://www.mediapolisjournal.com/2018/11/platform-urbanism-why-now-what-now/

- Barns, S. 2020. Platform Urbanism: Negotiating Platform Ecosystems in Connected Cities. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Barns, S. 2020a. “Re-engineering the City: Platform Ecosystems and the Capture of Urban Big Data.” Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 2. doi:10.3389/frsc.2020.00032.

- Bauböck, R., and L. Orgad, eds. 2020. “Cities Vs States: Should Urban Citizenship Be Emancipated from Nationality?” EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2020/16: Florence.

- Bauriedl, S., and A. Strüver. 2020. “Platform Urbanism: Technocapitalist Production of Private and Public Spaces.” Urban Planning 5 (4): 267–276. doi:10.17645/up.v5i4.3414.

- Bignami, F., and N. C. Hanakata. 2022. “Platform Urbanization and Citizenship: An Inquiry and Projection.“ In Platformization of Urban Life - Towards a Technocapitalist Transformation of European Cities, edited by A. Strüver, and S. Bauriedl. Bielefeld and London: Transcript.

- Bratton, B. 2015. The Stack: On Software and Sovereignity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Brenner, N. 2018. “Debating Planetary Urbanization: For an Engaged Pluralism.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 36 (3): 570–590. doi:10.1177/0263775818757510.

- Calzada, I., and C. Cobo. 2015. “Unplugging: Deconstructing the Smart City.” Journal of Urban Technology 22 (1): 23–43. doi:10.1080/10630732.2014.971535.

- Calzada, I. 2021. Smart City Citizenship. 1st ed. Waltham: Elsevier.

- Cardullo, P. 2021. Citizens in the ‘Smart City’: Participation, Co-Production, Governance. 1st ed. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Chang, F., and D. Das. 2020. “Smart Nation Singapore: Developing Policies for a Citizen-Oriented Smart City Initiative.” In Developing National Urban Policies, edited by D. Kundu, R. Sietchiping, and M. Kinyanjui, 425–440. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Christiaanse, K., A. Gasco, and N. C. Hanakata. 2019. “Grands Projets and Modelling Practices”. In The Grand Projet. Understanding the Making and Impact of Urban Megaproject (pp. 573–585). Rotterdam: nai010 publishers.

- Chua, H. C. E. 2019. “Survival by Technopreneurialism: Innovation, Imaginaries and the New Narrative of Nationhood in Singapore.” Science, Technology and Society 24 (3): 527–544. doi:10.1177/0971721819873202.

- The Commonwealth.org. n.d. “Singapore : Economy.” The Commonwealth.Org. Retrieved 16 September 2021 https://thecommonwealth.org/our-member-countries/singapore/economy

- Cuppini, N., M. Frapporti, and M. Pirone. 2015. “Logistics Struggles in the Po Valley Region: Territorial Transformations and Processes of Antagonistic Subjectivation.” South Atlantic Quarterly 114 (1): 119–134. doi:10.1215/00382876-2831323.

- Das, D., and J. J. Zhang. 2021. “Pandemic in a Smart City: Singapore’s COVID-19 Management through Technology & Society.” Urban Geography 42 (3): 408–416. doi:10.1080/02723638.2020.1807168.

- Data.gov.sg.2021. “Number of Licensed Hawkers under Government Market and Hawker Centres, Annual. https://data.gov.sg/dataset/number-of-licensed-hawkers-under-government-market-and-hawker-centres-annual

- Dumbrava, C. 2017. “Citizenship and Technology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Citizenship, edited by A. Shachar, R. Bauböck, I. Bloemraad, and M. Vink, 766–788, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Džankić, J. 2018. “A Brave New Dawn? Digital Cakes, Cloudy Governance and Citizenship Á La Carte.” In Debating Transformations of National Citizenship, IMISCOE Research Series, edited by R. Bauböck, 311–316. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Ennaji, M., F. Bignami, M. Moubtassime, M. Slighoua, and F. Boulaid. 2021. “Fez as a Locus of Migration Processes on the Move: Integration and Mutation of Citizenship.” The Journal of North African Studies 1–24. doi:10.1080/13629387.2021.1884854.

- Fischman, G. E., and M. Estellés. 2020. “Global Citizenship Education in Teacher Education Is There Any Alternative beyond Redemptive Dreams and Nightmarish Germs?” In Global Citizenship Education in Teacher Education: Theoretical and Practical Issues, edited by D. Schugurensky and C. Wolhuter, 102–124. New York London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

- Foley, R., and T. Miller. 2020. “Urban Techno-Politics: An Introduction.“ Science as Culture 29 (3): 309–18. doi:10.1080/09505431.2020.1759962.

- Gandy, M. 2004. “Rethinking Urban Metabolism: Water, Space and the Modern City.” City 8 (3): 363–379. doi:10.1080/1360481042000313509.

- Gandy, M. 2005. “Urban Political Ecology and the Politics of Urban Metabolism.“ In the Nature of Cities, edied by N. Heynen, and M. Kaika, 63–74. London, New York: Routledge.

- Hanakata, N. C., and F. Bignami . 2021. “Platform Urbanization and the Impact on Urban Transformation and Citizenship.” South Atlantic Quarterly 120 (4): 763–776.

- Hashem, I. A. T., V. Chang, N. Badrul Anuar, K. Adewole, I. Yaqoob, A. Gani, E. Ahmed, and H. Chiroma. 2016. “The Role of Big Data in Smart City.” International Journal of Information Management 36 (5): 748–758. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.05.002.

- Hemment, D., and A. M. Townsend, eds. 2013. Smart Citizens. http://futureeverything.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/smartcitizens1.pdf

- Henderson, J. C., O. Si Yun, P. Poon, and X. Biwei. 2012. “Hawker Centres as Tourist Attractions: The Case of Singapore.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 31 (3): 849–855. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.10.002.

- Huws, U. 2017. “Where Did Online Platforms Come From? the Virtualization of Work Organization and the New Policy Challenges It Raises. In Policy Implications of Virtual Work, edited by P. Meil, and V. Kirov, 29–48. Springer.

- Infocomm Media Development Authority. 2021. “SMEs Go Digital.” Infocomm Media Development Authority. Retrieved 22 September 2021 http://www.imda.gov.sg/programme-listing/smes-go-digital

- Isin, E. 2017. “Performative Citizenship.“ In The Oxford Handbook of Citizenship, edited byA. Shachar, S. Bauböck, I. Bloemraad, and M. Vink, 500–523. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Isin, E., and E. Ruppert. 2020. Being Digital Citizens. London and New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Jasanoff, S., and S.-H. Kim. 2009. “Containing the Atom: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and Nuclear Power in the United States and South Korea.” Minerva 47 (2): 119–146. doi:10.1007/s11024-009-9124-4.

- Katapally, T. R. 2020. “A Global Digital Citizen Science Policy to Tackle Pandemics like COVID-19.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 22 (5): e19357. doi:10.2196/19357.

- Kitchin, R. 2014. “The Real-Time City? Big Data and Smart Urbanism.” GeoJournal 79 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1007/s10708-013-9516-8.

- Kitchin, R. 2015. “The Promise and Perils of Smart Cities.” Computers and Law 3.

- Kylasam Iyer, D. (2019). “The City and Its Regimes of Citizenship”. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331628621_The_City_and_Its_Regimes_of_Citizenshipwebsite:doi:www.researchgate.net

- Laurent, B., L. Doganova, C. Gasull, and F. Muniesa. 2021. “The Test Bed Island: Tech Business Experimentalism and Exception in Singapore.” Science as Culture 30 (3): 367–390. doi:10.1080/09505431.2021.1888909.

- Lee, T. 2010. The Media, Cultural Control and Government in Singapore. London: Routledge.

- Lee, H. L. 2014. “Why Smart Nation: Our Vision.” In Presented at at the National Infocomm Awards Ceremony. Singapore.

- Lee, P. 2016. “Prepare to Ride Changes in Economy, to Seize New Opportunities Created: DPM Tharman.” The Straits Times, September 25.

- Leong, S., and T. Lee. 2021. “The Internet in Singapore: From ‘Intelligent Island’ to ‘Smart Nation.” In Global Internet Governance: Influences from Malaysia and Singapore, edited by S. Leong and T. Lee, 31–49. Singapore: Springer.

- Leszczynski, A. 2020. “Glitchy Vignettes of Platform Urbanism.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 38 (2): 189–208. doi:10.1177/0263775819878721.

- Levy, B., and M. Stewart. 2021. “The Evolving Ecosystem of COVID-19 Contact Tracing Applications.” Harvard Data Science Review. doi:10.1162/99608f92.2660ce5a.

- Luque-Ayala, A., C. McFarlane, and S. Marvin. 2016. “Introduction.“ In Smart Urbanism: Utopian Vision or False Dawn?, edited by S. Marvin, A. Luque-Ayala, and C. McFarlane, 1–15. London New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Mathiason, J. 2008. Internet Governance: The New Frontier of Global Institutions. London: Routledge.

- McCosker, A., S. Vivienne, and A. Johns, Eds. 2016. Negotiating Digital Citizenship: Control, Contest and Culture. London, UK: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Meijer, A., and M. Pedro Rodríguez Bolívar. 2016. “Governing the Smart City: A Review of the Literature on Smart Urban Governance.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 82 (2): 392–408. doi:10.1177/0020852314564308.

- Mezzadra, S., and B. Neilson. 2012. “Between Inclusion and Exclusion: On the Topology of Global Space and Borders.” Theory, Culture & Society 29 (4–5): 58–75. doi:10.1177/0263276412443569.

- Milan, S. 2018. “Cloud Communities and the Materiality of the Digital.” In Debating Transformations of National Citizenship, IMISCOE Research Series, edited by R. Bauböck, 327–336. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Minas, S. 2020. “‘Urban Citizenship’ in a Multipolar World.” In Cities Vs States: Should Urban Citizenship Be Emancipated from Nationality?, edited by R. Baubock and L. Orgad, 64–67. Fiesole: Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies.

- Morozov, E., and F. Bria. 2018. “Rethinking the Smart City: Democratizing Urban Technology.” Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung 5: 1–56.

- Ong, A. 2020. “Commentary: COVID-19 Has Revealed a New Disadvantaged Group among Us – Digital Outcasts.” Cannel News Asia, May 31.

- Oyedemi, T. 2015. “Internet Access as Citizen’s Right? Citizenship in the Digital Age.” Citizenship Studies 19 (3–4): 450–464. doi:10.1080/13621025.2014.970441.

- Pasquale, F. 2017. “From Territorial to Functional Sovereignity: The Case of Amazon.” Retrieved https://lpeproject.org/blog/from-territorial-to-functional-sovereignty-the-case-of-amazon/

- Quah, J. S. T. 2018. “Why Singapore Works: Five Secrets of Singapore’s Success.” Public Administration and Policy 21 (1): 5–21. doi:10.1108/PAP-06-2018-002.

- Quodling, A. 2016. “Platforms are Eating Society: Conflict and Governance in Digital Spaces.” In Negotiating Digital Citizenship: Control, Contest and Culture, edited by A. McCosker, S. Vivienne, and A. Johns, 131–146. London, UK: Rowman & Littlefield International.

- Roy, A. 2009. “The 21st-Century Metropolis: New Geographies of Theory.” Regional Studies 43 (6): 819–830. doi:10.1080/00343400701809665.

- Sadowski, J., and R. Bendor. 2019. “Selling Smartness: Corporate Narratives and the Smart City as a Sociotechnical Imaginary.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 44 (3): 540–563. doi:10.1177/0162243918806061.

- Sadowski, J. 2020. “Cyberspace and Cityscapes: On the Emergence of Platform Urbanism.” Urban Geography 41 (3): 448–452. doi:10.1080/02723638.2020.1721055.

- Sassen, S. 2002. “The Repositioning of Citizenship: Emergent Subjects and Spaces for Politics.” Berkeley Journal of Sociology 46: 4–26.

- Sassen, S. 2006. “The Repositioning of Citizenship and Alienage: Emergent Subjects and Spaces for Politics.“ In Migration, Citizenship, Ethnos, edited byY. M. Bodemann, and G. Yurdakul, 13–33. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sassen, S. 2016. “Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy.” Trajectories 26 (3): 62–84.

- Schlozman, K. L., S. Verba, and H. E. Brady. 2011. “Who Speaks? Citizen Political Voice on the Internet Commons.” Daedalus 140 (4): 121–139. doi:10.1162/DAED_a_00119.

- Schmid, C., and N. Brenner. 2011. “Planetary Urbanization.“ In Urban Constellations, edited by M. Gandy, 10–13. Berlin: JOVIS VERLAG.

- Schmid, C., O. Karaman, N.C. Hanakata, A. Kockelkorn, L. Sawyer, M. Streule, and K. Ping Wong. 2017. “Towards A New Vocabulary of Urbanisation Processes: A Comparative Approach.” Urban Studies 004209801773975. doi:10.1177/0042098017739750.

- SG Innovate. 2020. “Singapore Budget 2020 and What It Means for the Tech Ecosystem.” SG Innovate. Retrieved 22 September 2021 https://www.sginnovate.com/news/singapore-budget-2020-and-what-it-means-tech-ecosystem

- Shachar, A. 2020. “Beyond Open and Closed Borders: The Grand Transformation of Citizenship.” Jurisprudence 11 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1080/20403313.2020.1788283.

- Shaw, J., and M. Graham. 2017. “An Informational Right to the City? Code, Content, Control, and the Urbanization of Information.” Antipode 49 (4): 907–927. doi:10.1111/anti.12312.

- Shelton, T., and T. Lodato. 2019. “Actually Existing Smart Citizens: Expertise and (Non)participation in the Making of the Smart City.” City 23 (1): 35–52. doi:10.1080/13604813.2019.1575115.

- Söderström, O., and A.-C. Mermet. 2020. “When Airbnb Sits in the Control Room: Platform Urbanism as Actually Existing Smart Urbanism in Reykjavík.” Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 2. doi:10.3389/frsc.2020.00015.

- Speedtest. 2019. “Speedtest Global Index – Internet Speed around the World.” Speedtest Global Index. Retrieved 16 September 2021 https://www.speedtest.net/global-index

- Statistica. 2020. “Revenue Growth of Online Food Delivery in Singapore from 2018 to 2024.“ https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1183584/revenue-growth-online-food-delivery-singapore

- Storeng, K. T., and A. de Bengy Puyvallée. 2021. “The Smartphone Pandemic: How Big Tech and Public Health Authorities Partner in the Digital Response to Covid-19.” Global Public Health 16 (8–9): 1482–1498. doi:10.1080/17441692.2021.1882530.

- The Straits Times. 2018. “Rare Dip in Singapore’s Population Density Last Year.“ The Straits Times, January 16.Singapore. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/rare-dip-in-singapores-population-density-last-year

- Swyngedouw, E. 2005. “Metabolic Urbanization: The Making of Cyborg Cities.“ In the Nature of Cities, edited by N. Heynen, M. Kaika, and E. Swyngedouw, 21–40. London, New York: Routledge.

- Swyngedouw, E. 2019. “The Perverse Lure of Autocratic Postdemocracy.” South Atlantic Quarterly 118 (2): 267–286. doi:10.1215/00382876-7381134.

- Tjendro, J. 2021. “Food Outlets, Retailers to Get Help with Delivery Costs, Going Online with Reintroduced Schemes.” Channel News Asia May, 16. .https://www.channelnewsasia.com/business/food-delivery-retail-e-commerce-booster-packages-covid-19-1370481

- Tomasello, F. 2022. “From Industrial to Digital Citizenship: Rethinking Social Rights in Cyberspace. Theory and Society.” In Theory and Society. Submitted.

- UNCTAD. 2021. “Global E-Commerce Jumps to $26.7 Trillion, COVID-19 Boosts Online Sales.” Retrieved https://unctad.org/news/global-e-commerce-jumps-267-trillion-covid-19-boosts-online-sales

- Wiig, A., and E. Wyly. 2016. “Introduction: Thinking through the Politics of the Smart City.” Urban Geography 37 (4): 485–493. doi:10.1080/02723638.2016.1178479.

- The World Bank. 2016. “TCdata360: Households W/ Internet Access, %.” TCdata360. Retrieved 16 September 2021 https://tcdata360.worldbank.org/indicators/entrp.household.inet?country=SGP&indicator=3429&countries=KOR,CAN,HKG,JPN&viz=bar_chart&years=2016

- The World Bank. 2021. “Singapore GDP Per Capita 1960-2021.” Worldbank. Retrieved 16 September 2021 https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/

- Zuboff, S. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs.