ABSTRACT

This paper harnesses the strengths of the recent affective turn in citizenship studies. It makes three contributions to the literature. First, against proponents and critics of neoliberalism who neglect the reinventions of citizenship under ‘neoliberalism’, it emphasises the politics of hope advanced by socially excluded people. Second, while sympathetic to the affective turn in citizenship it addresses what it believes to be its key limitations: a neglect of the care people expect from the state and the feelings of solidarity that remain central to citizenship. Third, by reflecting on the experience of neighbourhood in Sao Paulo, the paper challenges the overwhelming focus of the affective citizenship literature on the Global North by drawing on perspectives from a key city in the Global South.

Hope for the future, we contend in this paper, remains central to the political imaginations of socially excluded people. However, the relationship between hope, social exclusion and citizenship is poorly understood. Much of the existing literature primes scholars to infer that social exclusion undermines citizenship, thereby spawning hopelessness, fear and mistrust. Indeed, the raging debate between triumphalist accounts of the global spread of ‘neoliberal’ market-based systems of economy and governance (Fukuyama Citation1992); against critical accounts of the same process (Harvey Citation2007; Davis Citation2006; Klein Citation2007) have ignored the ways in which socially excluded people seek to ‘reinvent citizenship’ (Isin Citation2012). Such neglect is commonplace. Even such icons as Mahatma Gandhi declared that the poor had no considerations other than that of the food they ate. Policy analysts point to the paucity of ‘aspirations’ among the socially excluded as a key factor for the perpetuation of poverty and inequality. In this vein, an influential organisation of global development such as the Bank (Citation2014, 4) tells us that ‘policy makers can help combat poverty by improving the aspirations of the poor’, reiterating the assumption that poor people have no aspirations, hopes and imaginations of the future. In this paper, we challenge this widespread assumption by analytically and empirically investigating the ‘the politics of hope’ (Appadurai Citation2013, 129) harboured by socially excluded people during the Covid-19 pandemics.

We do this by harnessing the strengths of the recent affective turn in citizenship studies, while addressing what we argue to be its limitations. This turn alerts us to the emotions and feelings that attend to the concept of citizenship. In this vein Fortier (Citation2016) upholds the importance of ‘unruly feelings’, the feelings people harbour despite not being authorised by states to do so. We draw a great deal on this insight, but depart from prevailing appropriations of the concept. Some of these appropriations dilute the importance of the state to understandings of citizenship. Others uphold the salience of difference within the political community. We don’t disagree on the importance of these ideas to affective citizenship. What we, however, want to do is to also emphasise the role of the state, especially the care expected from it in times of crisis. Furthermore, we want to highlight the importance of solidarity to understandings of citizenship.

The importance of the state and the role of solidarity in an ideational world dominated by neoliberal rationalities can hardly be overstated. Neoliberal rationalities condemn states as domineering, inefficient and controlling and undermine social cohesion by questioning the very concept of the social. Under the circumstances, ‘feelings of citizenship’ that focus on the state and emphasise solidarity during the ongoing pandemic are nothing short of unruly. We contend that a consideration of such feelings significantly enriches the valuable affective turn in citizenship studies.

This paper makes three contributions to the literature. First, against proponents and critics of neoliberalism who neglect the reinventions of citizenship under ‘neoliberalism’, it emphasises the politics of hope advanced by socially excluded people. Two, while sympathetic to the affective turn in citizenship it addresses what it believes to be its key limitations: a neglect of the care people expect from the state and the feelings of solidarity that remain central to citizenship. Three, by reflecting on the experience of neighbourhood in Sao Paulo, the paper challenges the overwhelming focus of the affective citizenship literature on the Global North by drawing on perspectives from a key city in the Global South.

1. Social exclusion and affective citizenship under COVID-19

Scholars have variously emphasised citizenship as a set of instituted processes (Beetham Citation1999; Somers Citation1993; Heater Citation1999); as political agency practiced through participation in civic life (Lister Citation2007; Ferguson Citation1999; Robins, Cornwall, and von Lieres Citation2008); as an ensemble of practices (Ong Citation1999; Lazar and Nuijten Citation2013; Gordon and Stack Citation2007; Stack Citation2012; Holston Citation2009; Ferguson Citation2015; Roy Citation2016) and as the ‘right to have rights’ (Arendt Citation1979; Somers Citation2008). In this vein, Isin (Citation2012) directs attention to the ways in which people ‘reinvent’ citizenship by imagining their membership of the political community beyond focusing on the state. We follow Isin’s (Citation2012) definition of citizenship as political subjectivity, and is thus understood as the ensemble of thoughts, interpretations, feelings, motivations, identities, memories and practices pertaining to the social distribution of power.

Elaborating this insight, but also signalling a crucial departure, Fortier (Citation2016) advances the notion of affective citizenship to emphasise that it is not the connection of people with their states or with one another that coheres citizenship. Rather, it is the ability to express claims of difference that cements a ‘feeling’ of citizenship (see also Di Gregorio and Merolli Citation2016; Fortier Citation2010). Nair (Citation2012) highlights the affective dimension of citizenship among socially excluded people, in which a shared sense of indignation against dominant narratives of the political community provides the opportunity to build connections between disparate individuals who ‘feel’ excluded by the state. Likewise, drawing on fieldwork from Slovenia, Wilmer (Citation2012) demonstrates the ways in which citizenship is produced through a contested engagement with art works. Roy (Citation2016), writing about the Indian State of Bihar, illustrates the centrality of contentious claims by subaltern social groups on social elites that underpins notions of citizenship. The notion of ‘cityzenship’, which emphasises people’s claims on urban spaces, takes this insight even further (Vrasti and Dayal Citation2016).

However, the emphasis on claims to difference undermines shared claims of care and solidarity. In their thoughtful introduction to ‘affective citizenship’ on the pages of this journal, Gregorio and Merolli (Citation2016, 936) suggest that ‘affective citizenship is therefore not simply freedom from the state, or a freedom from the established narratives of belonging, community and identity, but the ability to act and feel differently’. They go on to identify control, identity, and resistance as three important threads in defining affective citizenship. In critical conversation with this literature, we contend, alongside our interlocutors in Sao Paulo, that feelings of care and solidarity are also important to expressions of citizenship. Furthermore, the state remains central to people’s hopes and to their feelings of citizenship. When crises posed by poverty, vulnerability and inequality are exacerbated, as during the ongoing pandemic, people’s ‘feelings of citizenship’ express hopes for care by the state and solidarity from fellow members of the community. Indeed, as Linda Bosniak (Citation2006) illustrates, even when people are thought to be excluded from belonging to a political community, they insist on “feeling their own sort of citizenship, sometimes subverting the approved forms of membership.

Such ‘feelings of citizenship’ directly challenge prevailing neoliberal rationalities, understood as a norm that enjoins everyone to live in a world of generalized competition; it calls upon wage-earning classes and populations to engage in economic struggle against one another; it aligns social relations with the model of the market; … it even transforms the individual, now called on to conceive and conduct him- or herself as an Enterprise. (Dardot and Laval Citation2013, 8)

Our understanding of neoliberalism thus departs from standard meanings of the term rooted in economic policies that emphasise reduction of public investments. Rather, following Wendy Brown (Citation2015), we recognise neoliberalism as a subjectivity oriented towards increasing individual value and engage in constant social competition. Such a subjectivity is not only about individuals that exchange their interests, products and services in the market. Rather, the neoliberal subject is guided by competition as a fundamental guiding principle.

In following Brown’s (Citation2015) advice on recognising neoliberalism as a subjectivity, we are very mindful of Brenner, Peck, and Theodore (Citation2010)’s warning against regarding its equation with worldwide homogenisation. Indeed, their emphasis on the ‘variegated character of neoliberalisation’ (Brenner, Peck, and Theodore Citation2010, 184) serves as a useful reminder about its dynamic rather than static dimension. Appropriating this insight to Brown’s interventions on neoliberalism as a subjectivity, we pay special attention to forms of political imaginaries, in a context where many rationalities are under dispute, including old and new imaginaries, focusing on individual gains or collective social projects. In this sense, in parallel with older imaginaries related to collective social projects, there are emerging ones brought by the vivacious neo-pentecostal churches that have gained strength in Brazil, as well as by the emergence of a more conservative and individualistic thelos promoted by the Bolsonaro discourse.

In reflecting on citizenship, we are influenced by perspectives on its reconstitution that attend to how socially excluded people ‘demonstrate and perform their ability to construct collective hope’ (Appadurai Citation2013, 126–7). Scholarly approaches to studying the politics of hope may be anchored in what the anthropologist Arjun Appadurai calls people’s ‘capacity to aspire’, a navigational capacity through which they interpret the range of ‘possibilities’ that the future holds, and which they could achieve. Studying the ethics of possibility- ‘those ways of thinking, feeling, and acting that increase the horizons of hope’ (Appadurai Citation2013, 295)- provide useful empirical entry points into studying the ways in which people envisage their belonging in the political community and in relation to one another. ‘Hope’ is produced relationally, ‘in interaction and in the thick of social life’ (Appadurai Citation2004, 67). Hope is rarely defined only in relation to the self. It is not an individual property. When considering possibilities, people may hope for higher standards of living, increased respect from others in society, better-paying jobs, durable physical infrastructures, government responsiveness to social problems and embeddedness in family and community. Such hope-making is enmeshed in broader social, cultural and economic processes.

Drawing on contemporary formulations of agency that challenge social scientists to think beyond the active/ passive dichotomy (Procupez Citation2015), Jarett Zigon (Citation2018) argues that hope signals the motivation for ethical activity in moments of crisis and breakdown. Hope has, thus, been understood as not only about looking forward to a better future or of harking back to a ‘founding event that makes a certain kind of life possible’ (Badiou Citation2003) but also a way of persevering through the (present) life into which one has been thrown. Feelings of hope allows people to attempt to live ethically both for themselves and others, within the world in which one finds themselves. Such a conception distinguishes our approach from Crapanzano’s (Citation2003) formulation of hope as ‘a sort of passive resignation’ and from Miyazaki’s (Citation2004) suggestion that hope is holistically indeterminate and rooted in the uncertainties of the present time. Rather, we follow Bryant and Knight (Citation2019) in thinking about hope as a key ‘teleoaffect’, an impetus towards a possibility that is felt to be ethical. Hope is cultivated in the here-and-now with an aim to the future. As Back (Citation2021, 5) eloquently puts it, and we agree, hope ‘is an attention to the present and the anticipation that something unexpected will happen and emerge from its ruins’.

In operationalising hope, we are influenced by, but extend, Stef Jansen’s (Jansen Citation2016, 453–4) leads on defining hope. In this understanding, hope is, first and foremost, a set of dispositions, including the ensemble of knowledge, embodied inclinations, and affective investment that condition practices and are conditioned by them. Second, hope is future-oriented in being about potentiality rather than positionality. Such an understanding of hope implied a linear temporal reasoning that is not, however, unilinear or teleological: many potential alternatives are possible rather than just a single one. Third, the future-oriented dispositions are positively charged, in that they relate to a degree, however, wary or hesitant, of expectant desire. In other words, the outcomes to be desired are positively evaluated, even if not everyone (including the researchers) share them. Finally, hope is ‘disappointable’. It is possible that what people hoped for does not bear fruition. Uncertainty is integral to any definition of hope but that, of course does not mean hope is wholly uncertain (as Miyazaki Citation2004, Citation2006, Citation2010 would have it). Methodologically, such an understanding of hope allows us to glean data not only through verbal and non-verbal communication but through tracking of practices embedded in social relations. Such an understanding of hope builds on Jansen’s (Citation2013) own previous observations about the hopes harboured by people for their states to help them lead normal lives.

Challenging interventions that celebrated people evading the state and quietly resisting its imposition (especially Scott Citation1998; but also Graeber Citation2007), Jansen’s (Citation2013) interlocutors persuade him to recognise their ‘hopes for’ the state. In the context of war-torn Sarajevo, where his fieldwork was based, he reports frequent claims among people to be embedded in an institutional framework provided by the state that made ‘normal life’ possible. Such hopes for the state pertain to, in Jansen’s (Citation2015, 20) words, ‘the suppressed yearnings, loud clamourings and tireless struggles of people to be incorporated into griddings of improvement, and their investment in becoming, not to put too fine a point to it, part of legible populations’. Blending Appadurai’s insights with Jansen’s interventions, we arrive at an understanding of hope that is both relational and institutional. Such an understanding contrasts with a Camusian view that equates hope with resignation (Camus Citation2005). Rather, they urge us to recognise, with bell hooks (Citation2003), that hope is to be found in the unresigned stuggle for freedom. Indeed, for socially excluded people, such struggles are not a luxury but a daily fact of their existence. Whether they like it or not, they are left with little choice but to struggle to make themselves heard by states, to ensure that their claims are recognised as legitimate, and to act accordingly. As she reminds us,

Hopefulness empowers us to continue our work for justice even as the forces of injustice may gain power for a time. To live by hope is to believe that it is worth taking the next step” bell hooks (Citation2003: xiv-xv)

That next step could involve, as our interlocutors in Sao Paulo demonstrate, collective action. People could organise to bring pressure on local institutions of the state to deliver on their commitments, thereby holding them to account for their responsibilities. It could express the acts of citizenship that motivate people to seek out their state and demand that they take care of their citizens. It could focus attention on ‘those moments when, regardless of status or substance, subjects constitute themselves as citizens’ (Isin and Nielsen Citation2008, 18). Such acts inevitably ‘involve emotions, feelings, bodies’, inviting an attention to the ways in which these constitute membership in the political community. Such reflections on hope and citizenship assume poignant intellectual and practical significance in the context of the ongoing pandemic, which exacerbates the precarity, uncertainty and vulnerability of socially excluded people.

The cases presented in the next section exemplify how institutional and relational dimensions played out to facilitate communities’ mobilization and the production of hope in a poor region of the megacity of São Paulo during the pandemic. Firstly, we will situate the context of the city of São Paulo and describe the territory of Sapopemba, where our case studies take place, with its dynamics of poverty and marginalization, as well as its longstanding history of struggle and social mobilization. Next, we describe two experiences on which we build our case studies. The first is the experience of ‘Brigada pela Vida de Sapopemba’ (Sapopemba’s Life Brigade), an initiative that mobilized several social leaders from diverse policy sectors to fight the spread of the virus in the territory and put pressure on state action. The second experience reports the ‘Solidarity Neighbourhood Network of Sapopemba’ project, which sought to strengthen networks in the neighbourhood for emotional support in times of increased psychological suffering due to the pandemic, but also to its economic and social contingencies. It presents how subjects came together to support each other, aiming to promote care and solidarity among themselves and reassuring that the construction of a better future also depends on reinforcing bonds and a feeling of pertaining.

We have been working intermitantly in the region since 2001 following and documenting forms of political activism that struggled to improve local public health services (Coelho et al. Citation2019; Coelho and Schattan Citation2004; Coelho, Schattan, and Bettina Citation2010; Coelho and Schattan Citation2020). During this work we established a close relationship with historic community leaders from Sapopemba. When the first wave of the pandemics arrived we could not implement a previously planned field work. Nevertheless, at that time we have been informed by community leaders about new initiatives that were happening in the region to tackle the pandemic. We asked these leaders, as well as local health authorities if we could follow both informal and institutionalized meetings that were happening at that time to organize these initiatives. At this stage all the fieldwork done by our team was performed through virtual platforms. As researchers with an attentive sight for the ways social movements behave and act, we were impressed by how, amidst the catastrophic spread of the virus, the challenging circumstances posed by the pandemic has also convened local actors to re-imagine what a better future could look like and develop new projects for a movement that have been losing strength over the previous decades and disputing collective imaginaries about how state and society could interact.

2. Hope in Sapopemba during the Covid-19 pandemic

Our choice of the city of São Paulo is informed by a number of inter-locking factors. First, over the course of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, São Paulo emerged as one of the most significant cities in the Global South both in terms of population size and due to its economic significance in the national and wider-regional context. Second, we identify with the recent move in urban scholarship towards seeing globalisation and globalism as an ‘ordinary’ feature of daily life in cities of the Global South rather than as unique to top tier Global North cities. Finally, the choice of São Paulo as a significant city of the Global South helps to decentre the focus of affective citizenship theory from prevailing obsessions with paradigms of capitalist urbanisation in the Global North. As we shall see, the theory and practice of communities in the Global South offer pertinent insights on reclaiming the state and solidarity to their counterparts in the Global North. The leads provided by such reclamations in the Global South may well enrich affective citizenship in the Global North.

2.1. São Paulo megacity

São Paulo counts with a population of over 22 million inhabitants living in its metropolitan region. The megacity is the fourth largest in the world. This population circulates through the urban fabric daily, mostly in public transport that takes people from the outskirts of the city to its centre in returning trips every day. More than 1.7 million people travel to study or work between more central and peripheral areas of the metropole. This dynamic is mostly due to a great social and territorial inequality that characterizes the city, where affordable housing is only available far away from where jobs and education are offered, in richer areas close to downtown.

However, the profile of these structural inequalities has changed significantly over the last 30 years. Not that these inequalities have been overcome, but a significant number of welfare policies have been implemented in the poorest districts, guaranteeing greater access to several social protection services, leading to an improvement in several social indicators.

These accomplishments are undoubtedly the result of the creation and implementation of a comprehensive welfare system, that grew supported by the ‘citizenship’ constitution of 1988, enacted in tandem with the country’s political redemocratization. This system includes several sectoral policies in the areas of health, education, and social security, all of which are universal in nature and guaranteed as legal rights for all citizens of the country. However, the process of implementing these policies in the peripheries cannot be interpreted automatically and homogeneously. Between policy formulation and its effective implementation, one must pay attention to the politics involved and the struggles of social movements in negotiating with the State, especially in the poorest neighbourhoods. In the fight for ensuring that these rights are guaranteed, civil society has organized, and continuous social mobilization had to be sustained.

If we take the action of social movements as important elements for the implementation of policies at local level, this is due to their ability to dialogue, on the one hand, with a significant portion of the population, which provide them legitimacy, and on the other, to pressure different representatives of the State to satisfy local needs and enforce a set of rights. In Brazil, and especially in the municipality of São Paulo, since the democratization process, left-wing social movements have lead this dialogue with workers of the lowest socio-economic stractas. During the 1980s, local social movements that were previously centered on broader social rights and making strong opposition to the ongoing dictatorship government, have settled their roots in neighbourhoods and participatory arenas aiming to pressure political actors to implement social policies and public services (Cardoso Citation1995). Progressive segments of the catholic church were important actors in this process and in fomenting social imaginaries of a more equal and fair society. Whith time, a number of new of actors, such as new segments of the church, or new economic forces, such as the organized crime, have emerged in the field. These new players represented different political ideologies and imagined different collective projects that speaked, forged and responded to the dreams and hopes of the local population. This variety of organizational culture and profiles of mobilization has been proposed as an important variable to explain the significant differences between distinct parts of the city, either in terms of service provision and in its negotiating power with the State at the local level (Coelho et al. Citation2019, Citation2014; Coelho Citation2013).

These movements and changes has also been present in the electoral arena. If traditional social movements were associated with left-wing parties, especially the worker’s party (PT), since the 2000ʹs they have been losing voters, even in the peripheries that were an important stronghold of the party’s votes. The following table shows this trend at national, municipal and local level.

In this article we explore the role of a group, that, despite of its historic links with the Worker’s Party and its engagement in political mobilizations that nurtured the motivation of Sapopemba’s poorest residents to continue fighting and believing that a better future was possible, have been losing political strength. The pandemic mobilized and reinvigorated this group, opening a window of hope for them. The two experiences that are described below are part of this process.

2.2. Sapopemba’s profile

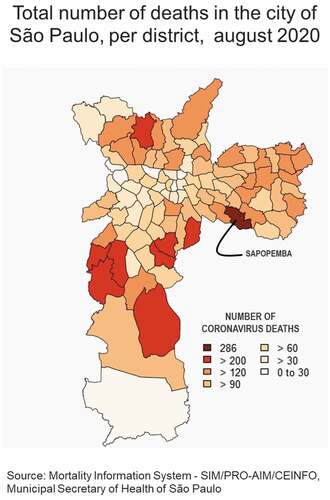

The district of Sapopemba has a population of 284,524 inhabitants, most of them are self-declared black or brown, and a fifth of this population lives below the poverty line. This is equivalent to almost 60,000 people. Located in the southeaster region of the city, Sapopemba is placed on an important route between central and eastern areas of the city.

In addition to the adversity faced by the local population and, as pointed above, the vulnerability of the district in times of pandemic, Sapopemba is also characterized by a long history of social mobilization. This has ensured important achievements over the last 30 years in welfare services, such as day care for children, elementary schools, expansion of the public transport network and the implementation of a wide network of health services of the public health care system (SUS). All these achievements are related with struggles and social mobilization of locally organized movements. Nonetheless, as aforementioned, similarly to the trend in the profile of the votes for PT vis-a-vis to its oponents at national and municipal levels, voters from Sapopemba have also been changing their electoral preferences (). This course point to a society in change, where projects and dreams are under dispute. A focus at the local level at the peripheries of São Paulo and the changes in the contour of social mobilization can help to better understand this process.

Table 1. Presidential election results, 2002–2018, percentage of votes.

Since the 1970s, Sapopemba has been the groundwork of intense political activity. The proliferation of improvised housing by those who could not afford to live closer to places where work is available have characterized the region as a place of marked social exclusion and vulnerability. Throughout the 1980s, catholic church priests, through ecclesial community-based movements and guided by liberation theology principles, started to articulate and animate intense social mobilization to improve the living conditions of the local population and demand basic fundamental rights. Sapopemba was, therefore, an important cradle from where many social movements from the peripheries have emerged during the democratization process (Richmond et al. Citation2020).

During the 1990ʹs, economic and social transformations happened re-defining the local landscape. Changes in the industrial sector led to an increase in unemployment and informality and, as in many favelas of Brazil, this scenario gave room to the expansion of organized crime and the subsequent escalation of violence derived by the combination of illegal markets and violent police action (Feltran Citation2011). In a context where few opportunities where available to the youth, crime have found a fertile ground offering perspectives of enrichment and success.

The first years of the 2000s can also be characterized as a moment of transition with the emergence of new fronts for social mobilization such as the fight against the youth genocide, especially of the black, the development of socioeducative services for the youth and the investment in child and adolescent education in the region. Also, during this first decade of twenty-first century, there was a major expansion of health and social protection services in the neighborhood, as well as other social policies, such as in public transportation and sewage.

Simultaneously to the growing presence of the State and the crime there was also the proliferation of several Neo-Pentecostal churches. Beyond the socio-assistencial programmes, these churches have been pointed as one of the rare altarnatives for breaking cicles of many young boys and girls that transit between the world of crime and disciplinary institutions (Richmond et al. Citation2020). Neo-pentecostals have been gaining more and more space in the socio-institutional fabric of Sapopemba. Diverging from the religious perspectives that led catholic churches to build aliances with local social movements in the 1980s, as did ecclesiastics guided by the theology of liberation, Neo-pentecostals are often guided by the theology of prosperity, and more frequently relies in individual action and financial and material wealth.

As Løland (Citation2020) notes, the emerging neo-pentecostal churches have contributed to naturalise the divine blessing of the market. Surrendering to God and trusting in Him blesses believers with material forms of wealth here and now (Garrard-Burnett Citation2013). Since prosperity can be attained through individual prayer and sacrifice, social planning or political action becomes unnecessary. Løland (Citation2020) quotes Edir Macedo, who leads the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (UKCG), a Pentecostal church with an estimated worldwide following of over 8 million, as outlining his theological vision thus:

It is impossible for the offering person not to have spiritual and financial return when the offering is according to the will of God. I believe that the Christians in their majority live a life on the border of poverty and misery because their offerings have demonstrated the lack of love, fear and respect for God.

Poverty and inequality are thus relegated to the spiritual realm, rather than caused by mechanisms of oppression, exploitation and marginalisation. Spiritualism, rather than the state, is called upon as a solution to the misery of the present, which could be most effectively countered by true belief rather than public intervention (Garrard-Burnett Citation2013). Furthermore, the greater the belief, the higher the chances of material properity: believers are called upon to make ever greater sacrifices to God (and buying salvific goods in the church), in order to enhance their chances of securing wealth.

In fact, by the end of the 2010s, we found in Sapopemba a diverse territory marked by a diffuse presence of the State, either by providing social services and by the tenancy of the police, but also by the pervasive presence of the organized crime, as well as distinct religious groups. Furthermore, we also observe a myriad of social organizations with different roles in the distributions of public services, comprising a fragmented landscape of political activity in the territory. This ensemble of organizations and institutions offers particular visions and collective projects for the community, often divergent and in dispute. Still remarkable, is the way people often circulate between this imbricated network of sociabilities, frequently participating in different manners in many of these concurrent spaces (Telles and Hirata Citation2007).

The 2020ʹs begun with the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic. An important contingency of the pandemic for Sapopemba dwellers was the stoppage in labour market and the suspension of activities that represented significant sources of income for informal workers. Faced with food insecurity, several social initiatives, including governamental ones, started to distribute food baskets for families in need. As one of our field interlocutors have pointed out, there was an intense competition between local institutions to intermediate these goods. Not long ago, the straight relationship between longstanding social movements and political actors and policy makers, was the unequivocal path to reach vulnerable populations of the district. During the pandemic, the variety of new social actors have changed this scenario. Many of the goods distributed by the municipal townhall were sent to Evangelical churches to be distributed among the poor, bypassing longstanding social movements.

2.3. Affective citizenship in times of the COVID-19 pandemic

With the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, despite the structured network of health and social protection services in the district, the containment of the spread of the SARS-COV-2 virus did not work well. Certainly, the social and economic context did not facilitate the implementation of measures such as social distancing and hygiene. At the same time, the territory was also divided concerning how to handle the pandemic. When curfews were decreed to avoid agglomerations in the state of São Paulo, many evangelical churches refused to close their doors. A judicial battle was uphold at the national level, claiming that individuals have the right to attend religious cults, even if this attendance could place the majority of the population in risk. Such position, re-invoked divisions between catholic representatives (as the national confederation of bishops, that were aligned to scientists defending the closure of religious temples) and neo-pentecostals (represented by the ministry of the supreme court appointed by president Bolsonaro and the national association of evangelic jurists).Footnote1 Similarly, there were reports that many of neo-pentecostal communities have spread guidance to correligionaries to refuse the intake of vacccines and there were rumors that evangelical groups have activelly engaged in spreading fake news about the virus, helping to politicize the pandemic.Footnote2

Faced with this crisis, and the presence of antagonic orientations about how to behave local leaders related to political parties, social movements, NGOs and religious organizations, gathered to identify demands and potential responses to overcome the desolate scenario that was taking place during the COVID-19 pandemic. These leaders, previously organized around longstanding social movements advocating for improvements in health, housing, childhood, adolescence, and human rights in the territory, have recognized the intersectoral challenge posed by the pandemic and joined efforts to organize a coalition oriented by the scientific community to overcome the contingencies of the crisis. Inspired by the Emergency Health Brigade (organized in Brazil’s Northeast), Sapopemba’s initiative aimed to combat the pandemic by defending rights, demanding accountability and supporting the state, while also promoting teaching and learning from the population. Online meetings brought the welcome surprise of rapid progress:

‘It seems that we were even able to gather more, each person at their work or at home, discussing and highlighting solutions for this very difficult time that we are experiencing. I was excited; everything was so fast. We started in April and on May 25 (2020), we approved the Life Brigade Manifesto’. (Francisca Ivaneide, a movement member)

The Brigade implemented working groups in different neighbours of Sapopemba pressuring local authorities to apply concrete preventive actions and facilitating efforts to find locally appropriate solutions to their specific problems. One of the Brigade’s first initiatives, with the help of politicaly aligned city commissioners and congressional members, was to hold meetings with different municipal government departments to identify preventive actions.

Citizens and health councillors, that are nominated to represent civil society at the SUS local participatory councils, public officials and providers, were informed by Brigade members on how to connect digitally and invited to scheduled meetings. The first of these held on June 25th of 2020 involved around 70 people. This meeting called for more transparency and details on data about the distribution of cases and deaths in each sub-area of the region.

When provided with this data, the Brigade discussed with personnel in the 16 SUS Basic Health Units to identify and jointly co-ordinate actions and priority groups. One task force handed out protective masks donated by companies on the streets and talked with passers-by and merchants. Black cloths were placed on gates as a sign of mourning for the deaths in the community and a car with loudspeaker was provided by a union to honour victims. By mobilizing people who hold credibility in the region and using appropriate language to publicize the risks and number of deaths in different areas of the territory, this initiative helped to raise public awareness of the seriousness of the pandemic.

The Brigade carried out similarly co-ordinated actions around education. It has organized debates with school communities regarding the return to classes in September, given stark divisions in opinions around this return to school.

Brigade members have called attention to situations where infection risk is high, such as street markets, which remained opened during quarantine. The affordable prices make these markets very popular leading to crowding. The Brigade discussed with the Secretariat of Sub-Districts to rather organise markets in one long line to prevent agglomeration.

The Brigade also carried out a survey to gain an in-depth understanding on risk factors, the impacts of the pandemic on the lives of residents and the difficulties they experienced in implementing responses.

Finally, the advancement of the vaccination roll-out, and the simultaneous delay in the campaign in the poorest neighbourhoods of the city, including the district of Sapopemba, led the group to elaborate proposals to leverage a vaccination campaign focused on the territory. The group reinforced that age criteria defined by the government implied in strong bias, given that the age pyramid is significantly different in rich and poor areas, reinforcing inequalities. The brigade has advocated for a campaign to vaccinate dwellers of the district in a short period of time. The idea was to create a ‘vaccine bubble’ that could break the spread of the virus within and outside the community. Conversations were held with policy makers from the municipal townhall, state government and managers of public laboratories as the Butantã Lab.

‘When the movement moves, the Secretariat moves’. Brigade members and public health managers both referred to this mechanism, showing the support that the Life Brigade brings to the SUS. The actions taken show how knowledge of local dynamics and links between social leaders and public managers has facilitated the work of the local health system and reinfoirced its links to the broad public. In the harsh realities of Sapopemba, the Brigade innovated through promoting integrated action between social movements and health, social assistance, education and justice sectors to implement concrete actions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The political relationships and the trust accumulated over many years helped Brigade leaders to link sectors of civil society organized in different areas of social policy. To foster inter-sectorial actions was new, as since the 1980ʹs the movements became fragmented in order to deal with the state logic of organizing different social policies, that is to say: health, education, social assistance, housing, human rights and so forth. It was also new to value the knowledge of those experiencing the local reality who are familiar with its residents’ needs, as we could see, for example, in the discussions about how to organize the street market or the age criteria for vaccination. This innovative focus, together with the joint action by the movement with the region’s public services and managers were made possible by previous processes of mobilization and institutional building. During these processes a feeling of citizenship that connect the subjects around the believe that they have rights and need to press the State to deliver accordingly was nurtured. This environment enabled a convergence of strategies, knowledge, information and action to support prevention, promotion and rights enabling the flourish of hope about the possibilities of building a new future.

The Brigade initiative worked in a highly disputed political arena, providing resistance to a form of action based on denialism and the wide spread of fake news. The brigade action, sought to gather evidence-based information about the the contagion in the region and established close connection with public health advocators to define responsible actions.

Simultaneously to the escalation of the pandemic in the city of São Paulo, and unfolding economic and social contingencies, social organizations of Sapopemba soon began to worry about long-lasting impacts that the situation could generate on the mental life of the local population. Faced with grief, stresses in domestic life (often demanding in terms of care production for children and elderly households), loss of income, among other circumstances, situations that were already problematic before the pandemic on the outskirts of São Paulo, have become even more urgent and frequent. A worsening in the mental health of the dwellers of Sapopemba became evident with the increasing reports of suffering and anguish.

Furthermore, welfare services and institutions of religious and spiritual support, where people frequently turn for help and emotional support, were also closed, leaving people to handle problems individually and without the networks of support on which they would usually count on.

It was in this context that the Sapopemba Human Rights Centre (CDHS), an local NGO that works across several policy sectors engaged in fostering citizenship in the district, resorted to an ongoing partnership with the Institute of Psychiatry of the São Paulo State University School of Medicine (IoP- FMUSP), to tackle this process of degradation of the mental health of the local population.

Inspired by a North American project implemented in the city of Baltimore,Footnote3 the CDHS and a team of researchers from the IoP created a community-based project that sought to strengthen bonds of solidarity and emotional support among community members themselves. Entitled Sapopemba’s Solidarity Neighbourhood Network (SSNN), the project soon gained repercussion in the region. CDHS quickly mobilized its local networks and in a short time, through virtual meetings, the SSNN articulated with other initiatives that sought to respond to the contingencies of the pandemic, such as the Life Brigade and others. Graphic designers from the community developed a logo that expressed the project idea in a way that allowed an easy understanding of the project proposal.

One of the first concerns of the SSNN was to understand in greater depth the changes in the community’s daily life and what types of suffering were being produced in that context. Simultaneously, believing in the potential of the support that could be provided by community peers, the project sought to strengthen supportive networks and a spirit solidarity through a simple technique of empathetic listening and emotional support, which does not require any technical or professional training.

Through the dissemination of the initiative in a rich network of WhatsApp groups of various entities of social action working in the neighbourhood, a group of volunteers was formed. The group was initially composed by 10 local residents, including people of different age groups, being the younger an 18-year-old student of psychology and the older a 45-year-old social assistant that worked as a hairdresser. Volunteers also had different religious backgrounds, including neo-pentecostals, catholics and of afro-Brazilian matrices. The group was composed equally of man and women, the majority identifying themselves as white, although about one-third self-declared as black. The motivation for the participation of these volunteers came from different places. There was, in the first place, a strong sense of belonging in the community and a desire to help fellow community residents deal with the difficulties posed by the pandemic. Volunteers resorted to arguments, ranging from religious morality, related to the importance of helping others, to an engaged political ideal, about the need to support community fellows who suffered from persistent structural issues, or even of a professional nature, including young people undergoing training in psychology, teachers and social service workers of the territory who sought to know more about psychological suffering.

Under the project ‘Mental Health in Adversity’, the team from the IoP developed a training material that consisted of a booklet with suggested topics to be explored in the empathetic listening, such as changes in the daily life, feelings, fears and worries, community bonds, health conditions, employment, income, and division of domestic tasks, perceived security and violence and perspectives for the reopening after the pandemic. Later, volunteers were trained and provided phone credits so that they could make the calls without having to bear the cost of the calls.

An enrolment list for the project was made available at the CDHS and publicized at sensitive campaigns developed by the centre, such as the distribution of food baskets, where those who wished to receive a supportive phone call could leave their contact details.

For 2 months, both teams from the IoP and CDHS held follow-up meetings with the volunteers to support them in performing empathetic listening and in better understanding the needs of the local population. Special attention was given to providing support that was not guided by clinical practice, but one that was especially interested in helping people to cope with experiences of social suffering during a period of collective distress.

The SSNN was formed in a very natural way, led by the interest of volunteers and local organizations in learning and providing emotional support to their fellow counterparts. It was consensus that mental health is a serious and urgent problem that needs to be addressed and that there is a strong social component in the production of this suffering, therefore being perceived as unjust. Surprisingly, the potential of the volunteers in understanding the struggles of their neighbours and in forging strategies to overcome them, showed paths for the co-production of care that goes far beyond the provision of mental health services. The following quote demonstrates the learning process of the volunteers and its potential:

Sometimes the person is very hurt, feeling very rejected, they listened a lot of ‘no’, they start to shield themselves and think that there is no one around who is good, that there is no one to help, that no one cares about the others, that is every man for himself. And for us to show that there is a path, that even strangers can help. We often don’t find this support even within our families. But there are also people out there who want to help who are concerned about these issues, because these are everyone’s issues. Everybody has a problem in the family (…). And we see that other people’s problems have a lot to do with ours own. We live in the same community and we have also experienced the problems of the others, because they are the same problems we face. We are in the same community, in the same boat, let’s say. Then you see that there are other people you can count on, that it’s not just bad people that exist in the world. It’s very important. (Quote taken from supervision of 11/05/2020).

Emotional suffering and psychological distress were expected to be experienced by the population in the difficult circumstances that unfold from the pandemic. Therefore, the focus of the initiative was targeted at strengthening solidarity, supporting community counterparts, and listening to the experiences of social suffering. The idea of co-production emerged from a concern not to address the experiences of suffering in biomedical terms, but rather as rooted in a specific context of social exclusion and poverty.

The quote mentioned above speaks of an issue that is not only situated on the present, but also focused on the future. It reinforces the importance of rescuing hope among those who have already lost it. For the volunteers of the project, as well as for CDHS, it was an important political act to keep hope alive, even when people do not see it anymore in their surroundings. To do so, it was important to reach the affective dimension of citizenship and belonging. By connecting local volunteers with a lived experience in the territory to their fellow neighbours, the initiative provided the opportunity to build connections between disparate individuals who ‘feel’ excluded.

Interestingly, the SSNN have found in the territory a wide sense of community support across volunteers of different believes and worldviews, including neo-pentecostals and catholics, people that socialize with members of the organized crime and workers of social programmes. When the practices of citizenship were seen at the grass-roots level, it was possible to see a pervasive position of solidarity and desire to support community counterparts in suffering. The distance between the political discourses and the disputes over imaginaries, were actually secondary to a citizen ethos raized by an idea of solidarity and of doing the good.

These experiences portray a moment where hope and solidarity were produced amid a severe crisis in a very vulnerable context and where distinct collective projects were in dispute. This report does not aim to draw a picture of the territory in its multiplicity of actors mobilizing for social transformation. Quite the opposite, we do recognize that the scenario is heterogeneous and in a significant process of transformation. New actors are emerging, changing the ways collective action used to work. An example of this shift was the report of local interlocutors about the changes in the profile of social actors engaged in the distribution of food baskets by the municipal town hall, or the municipal election results in 2020, with the PT receiving a meager portion of votes, not even reaching the runoff election and the choice of the majority of Sapopemba’s voter’s for the center right-wing candidate of the social-democrat party (PSDB).

3. Feeling like a citizen

The affective turn in citizenship studies usefully urges us to consider the importance of thinking and feeling differently (Di Gregorio and Merolli Citation2016). In this vein, Fortier (Citation2016) reminds us about the importance of ‘unruly feelings’ in understandings of citizenship: such unruly feelings refer to the expression of political emotions that are not authorised by states but are nevertheless demonstrated by people. Di Gregorio and Merolli (Citation2016) elaborate the concept of affective citizenship by directing our attention to three themes: (1). Control; (2) Identity and (3) Resistance. The theme of control is explored in relation to the day-to-day actions of the state, including the values, affects and ethics produced by it. Noting the limitations of looking towards the state as a site of citizenship, they and their collaborators look towards the theme of identity to reflect on the ways in which affect is used to produce and build identities outside of the state. A consideration of such identities leads them to reflect on the theme of resistance, to think about the deployment of affect ‘against the state, capitalist economic structures, and its related racist, gendered and colonial logics’ (Di Gregorio and Merolli Citation2016, 938). By reflecing on the ways in which plucky little people defy all odds to throw a spanner in the works by states and to conserve their difference against governmental technologies of homogenisation, this literature would have us believe that affective citizenship is only demonstrated when people emphasise their difference and conceptualise political community beyond the state.

Our fieldwork compels us to disagree. We insist that the affective turn in citizenship studies consider the hopes people harbour for the state especially when their social exclusion are exacerbated by crises such as the ongoing pandemic. The claims advanced by the Sapopemba Life Brigade on their local authorities and their collaboration with the SUS participatory councils suggests that states remained central to their acts of citizenship. They demanded transparency in data by officials and insisted on policy being based on it. Holding to account a state that was not being able to deliver accordingly, the Sapopemba Life Brigade sought more, not less, of the state. It was thus interrogating the logics that celebrate state retrenchement as exemplars of good governance. Rather than acquiescing with this logic and turning to voluntary agencies and community-based organisation alone, Brigade Members sought out elected councillors, public health officials and ensured collaboration between civil society and social policy. The perspectives offered by proponents of affective citizenship would be further enriched by considering the feelings of care expected from the state.

Through the Solidarity Neighbourhood Network, Sapopemba’s residents further demonstrate the importance of solidarity to understandings of affective citizenship. Faced with a pandemic that made in-person collective meetings a threat to public health, the Network fostered solidarity through virtual channels, especially Whatspp groups. Volunteers were trained to ‘empathetically listen’ to members of the community, enabling them to feel that they belonged. Although they could not provide solutions to people’s problems, the Network conveyed to members that they were cared for by others in the community. In the light of this observation, we urge that formulations of affective citizenship consider seriously the feelings of solidarity that convey to people that they belong to the political community.

Does our insistence on focusing on the state and attending to the value of solidarity mean that all citizenship is necessarily affective? Do these inclusions render the formulation of ‘affective citizenship’ redundant? We don’t think so, and remain in agreement with Fortier’s (Citation2016) suggestion that ‘affective citizenship focuses on one aspect of how citizenship “takes place” by emphasising how it is affective – how it involves emotions, feelings, bodies’. She upholds the importance of ‘unruly feelings’, the feelings people harbour despite not being authorised by states to do so. Indeed, in line with her insights, we insist that the emotions and feelings associated with citizenship take into account the hopes people harbour in favour of the state and of solidarity. Sapopemba’s residents ‘feel like citizens’ when they insist that the state care for them. They ‘feel like citizens’ when they demand and obtain solidarity from fellow members. These expectations and feelings have been facilitated, we argue, by a context where relational and institutional networks were nurtured by previous processes of political mobilization and welfare institutions building.

Such feelings of citizenship challenge the prevailing neoliberal subjectivities that uphold individual competition rather than social support in attaining well-being and endorse the unravelling of society (it was Margaret Thatcher after all, one of the greatest enthusiasts of neoliberalism, who had declared there was no such thing as society). These feelings illustrate a refusal to be contained within the affective boundaries authorised by those in power that encourage people to be autonomous, atomised and competing with one another. By doing so, Sapopemba’s residents compel us to focus on the state (rather than spiritualism) and insist on social solidarity (rather than spiritual competition) as key to the welcome affective turn in citizenship studies.

Our discussion of affective citizenship in Sao Paulo, a key city of the Global South, challenges the overwhelming focus of the existing literature on the Global North. The focus of our interlocutors on the care they expect from the state and their attempts to cement social solidarity interrogate the premises of neoliberal subjectivity that aims to dilute both. By emphasising care from the state and solidarity with one another, their affective expressions reinvent citizenship. Such reclamations of state and solidarity in the Global South offer strategies for invigorating affective citizenship elsewhere, including in the Global North.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Indrajit Roy

Indrajit Roy is Senior Lecturer- Global Development Politics at University of York, UK. He is Co-Director Interdisciplinary Global Development Centre and Principal Investigator of the ESRC-funded Citizenship futures: The politics of hope. He is the author of Politics of the poor: Negotiating democracy in contemporary India, published by Cambridge University Press in 2018.

Vera Schattan P Coelho

Vera Schattan P Coelho is a Senior Researcher at the Brazilian Center of Analysis and Planning (Cebrap), she teaches at the Federal University of ABC (UFABC), São Paulo, Brazil and is an associate researcher at CEM/University of São Paulo. She was a visiting fellow at the Hauser Center, Kennedy School, Harvard University, USA; the Institute of Development Studies, Sussex University, UK; Torcuato di Tella University, Argentina; and the Social and Economic Studies Center of Uruguay (CIESU). Her research interests are: citizenship, citizen engagement on the policy process, political participation, accountability, social policies, democracy and development.

Felipe Szabzon

Felipe Szabzon is a postdoctoral fellow of the “Covid-19 and mental health” project at the Department of English, Germanic and Romance Studies (ENGEROM) of the University of Copenhagen. He is also a research associate of the Section of Psychiatric Epidemiology of the São Paulo Medical School from the University of Sãojit Paulo (NEP-FMUSP) and a Permanent Researcher at the Brazilian Centre for Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP). He holds a double PhD degree in Dynamics of Health and Social Welfare from the National School of Public Health (Portugal) and the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS – France); an MSc in Public Health (USP) and a bachelor’s in clinical psychology (PUC-SP). He has previous experience working at the National Mental Health Programme at the Portuguese Ministry of Health. His main interests rely upon the analysis of mental health policy as well as on global mental health practices and how these imply in subjective experiences lived by people in contexts of adversity and social exclusion. He has also co-founded the Platform for Social Research in Mental Health in Latin America (PLASMA).

Notes

1. ‘Worship released or not in the pandemic? Understand the controversy involving churches, government and the Judiciary’ (Available at: https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-56644637) and ‘Supreme Court decides whether temples can stay open in the pandemic’ (Available at: https://www.correiobraziliense.com.br/politica/2021/04/4916652-supremo-decide-nesta-quarta-se-templos-podem-ficar-abertos-na-pandemia.html)

2. ‘Evangelical groups helped spread Bolsonaro’s fake news about the left and pedophilia’ (Available at: https://apublica.org/2020/07/grupos-evangelicos-e-olavistas-ajudaram-a-espalhar-fake-news-de-bolsonaro-sobre-esquerda-e-pedofilia/) and ‘Lula and Moro are victims of fake news promoted by evangelicos pro Bolsonaro’ (Available at: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2022/02/lula-e-moro-sao-vitimas-de-fake-news-promovidas-por-evangelicos-pro-bolsonaro.shtml)

References

- Appadurai, A. 2004. “The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition.” In Rao, V. and Walton, M., (eds.) Culture and Public Action, Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, California, 59-84.

- Appadurai, A. 2013. The Future as a Cultural Fact: Essays on the Global Condition. London: Verso.

- Arendt, H. 1979. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt Brace.

- Back, L. 2021. “Hope’s Work.” Antipode 53 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1111/anti.12644.

- Badiou, A. 2003. Saint Paul: The Foundation of Universalism. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Bank, W. 2014. “World Development Report 2014: Risk and Opportunity—Managing Risk for Development.” Washigton D.C. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/16092

- Beetham, D. 1999. Democracy: A Beginner’s Guide. Oxford: Oneworld Publishers.

- Bosniak, L. 2006. The Citizen and the Alien: Dilemmas of Contemporary Membership. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Brenner, N., J. Peck, and N. Theodore. 2010. “Variegated Neoliberalization: Geographies, Modalities, Pathways.” Global Networks 10 (2): 182–222. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0374.2009.00277.x.

- Brown, W. 2015. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. New York: Zone Books.

- Bryant, R., and D. M. Knight. 2019. “The Anthropology of the Future.” Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108378277

- Camus, A. 2005. Summer In Algiers. London: Penguin UK.

- Cardoso, R. 1995. “Mudança Sociocultural e Participação Politica Nos Anos 80.” In Lições Da Década de 80, edited by L. Sola and L. M. Paulani, 193–200. São Paulo: EDUSP.

- Coelho, V., and P. Schattan 2004. “Brazil’s Health Councils: The Challenge of Building Participatory Political Institutions.” 2. IDS Bulletin. Vol. 35. IDS Bulletin 35. Sussex.

- Coelho, V., and P. Schattan. 2013. “What Did We Learn about Citizen Involvement in the Health Policy Process: Lessons from Brazil.” Journal of Public Deliberation 9: 1. doi:10.16997/jdd.161.

- Coelho, V., and P. Schattan. 2020. “What Did We Learn about Citizen Involvement in the Health Policy Process: Lessons from Brazil.” Journal of Deliberative Democracy 9: 1. doi:10.16997/jdd.161.

- Coelho, V., P. Schattan, and V. L. Bettina. 2010. “Mobilising for Democracy: Citizen Engagement and the Politics of Public Participation.” In.” Zed Books 7: 1–30.

- Coelho, V., P. Schattan, L. M. Marcondes, and M. Barbosa. 2019. “Accountability e Redução Das Desigualdades Em Saúde: A Experiência de São Paulo.” Novos Estudos - CEBRAP 38 (2): 323–349. doi:10.25091/S01013300201900020003.

- Coelho, V., P. Schattan, F. Szabzon, and M. F. Dias. 2014. “Política Municipal e Acesso a Serviços de Saúde São Paulo 2001-2012, Quando as Periferias Ganharam Mais Que o Centro.” Novos Estudos - CEBRAP 100 (November): 139–161. doi:10.1590/S0101-33002014000300008.

- Crapanzano, V. 2003. “Reflections on Hope as a Category of Social and Psychological Analysis.” Cultural Anthropology 18 (1): 1. doi:10.1525/can.2003.18.1.3.

- Dardot, P., and C. Laval. 2013. The New Way of the World on Neoliberal Society. London: Verso Books.

- Davis, M. 2006. Planet of Slums. London: Verso.

- Feltran, G. 2011. Fronteiras de Tensão: Política e Violência Nas Periferias de São Paulo. São Paulo: Editora Unesp.

- Ferguson, J. 1999. Expectations of Modernity Myths and Meanings of Urban Life on the Zambian Copperbelt. California: University of California Press.

- Ferguson, J. 2015. Give a Man a Fish: Reflections on the New Politics of Distribution. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Fortier, A.-M. 2010. “Proximity by Design? Affective Citizenship and the Management of Unease.” Citizenship Studies 14 (1): 17–30. doi:10.1080/13621020903466258.

- Fortier, A.-M. 2016. “Afterword: Acts of Affective Citizenship? Possibilities and Limitations.” Citizenship Studies 20 (8): 1038–1044. doi:10.1080/13621025.2016.1229190.

- Fukuyama, F. 1992. “Capitalism and Democracy: The Missing Link.” Journal of Democracy 3 (3): 100–110. doi:10.1353/jod.1992.0045.

- Garrard-Burnett, V. 2013. “Neopentecostalism and Prosperity Theology in Latin America: A Religion for Late Capitalist Society.” Iberoamericana – Nordic Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 42 (1–2): 21. doi:10.16993/ibero.32.

- Gordon, A., and T. Stack. 2007. “Citizenship beyond the State: Thinking with Early Modern Citizenship in the Contemporary World.” Citizenship Studies 11 (2): 117–133. doi:10.1080/13621020701262438.

- Graeber, D. 2007. Possibilities: Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire. Oakland, CA: AK Press.

- Gregorio, M. D., and J. L. Merolli. 2016. “Introduction: Affective Citizenship and the Politics of Identity, Control, Resistance.” Citizenship Studies 20 (8): 933–942. doi:10.1080/13621025.2016.1229193.

- Harvey, D. 2007. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Heater, D. 1999. What Is Citizenship? Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Holston, J. 2009. Insurgent Citizenship: Disjunctions of Democracy and Modernity in Brazil. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- hooks, B. 2003. Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope. London: Routledge.

- Isin, E. F. 2012. “Citizenship after Orientalism: An Unfinished Project.” Citizenship Studies 16 (5–6): 563–572. doi:10.1080/13621025.2012.698480.

- Isin, E. F., and G. M. Nielsen. 2008. Acts of Citizenship. London & New York: Zed Books.

- Jansen, S. 2013. “Hope For/Against the State: Gridding in a Besieged Sarajevo Suburb.” Ethnos 79 (2): 238–260. doi:10.1080/00141844.2012.743469.

- Jansen, S. 2015. “Yearnings in the Meantime.” Berghahn Books. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qcxhw

- Jansen, S. 2016. “For a Relational, Historical Ethnography of Hope: Indeterminacy and Determination in the Bosnian and Herzegovinian Meantime.” History and Anthropology 27 (4): 447–464. doi:10.1080/02757206.2016.1201481.

- Klein, N. 2007. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York: Metropolitan Books.

- Lazar, S., and M. Nuijten. 2013. “Citizenship, the Self, and Political Agency.” Critique of Anthropology 33 (1): 3–7. doi:10.1177/0308275X12466684.

- Lister, R. 2007. “Inclusive Citizenship: Realizing the Potential.” Citizenship Studies 11 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1080/13621020601099856.

- Løland, O. J. 2020. “The Political Conditions and Theological Foundations of the New Christian Right in Brazil.” Iberoamericana – Nordic Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 49 (1): 63–73. doi:10.16993/iberoamericana.495.

- Miyazaki, H. 2004. The Method of Hope: Anthropology, Philosophy and Fijian Knowledge. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

- Miyazaki, H. 2006. “Economy of Dreams: Hope in Global Capitalism and Its Critiques.” Cultural Anthropology 21 (2): 147–172. doi:10.1525/can.2006.21.2.147.

- Miyazaki, H. 2010. “Chapter 15. The Temporality of No Hope.” In Ethnographies of Neoliberalism, edited by Carol J. Greenhouse, 238-250. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press doi:10.9783/9780812200010.238.

- Nair, P. 2012. “The Body Politic of Dissent: The Paperless and the Indignant.” Citizenship Studies 16 (5–6): 783–792. doi:10.1080/13621025.2012.698508.

- Ong, A. 1999. Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Procupez, V. 2015. “The Need for Patience: The Politics of Housing Emergency in Buenos Aires.” Current Anthropology 56 (S11): S55–65. doi:10.1086/682240.

- Richmond, M. A., M. Kopper, V. C. de Oliveira, and J. G. Placencia. 2020. Espaços Periféricos: Política, Violência e Território Nas Bordas Da Cidade. São Carlos: EdUFSCar.

- Robins, S., A. Cornwall, and B. von Lieres. 2008. “Rethinking ‘Citizenship’ in the Postcolony.” Third World Quarterly 29 (6): 1069–1086. doi:10.1080/01436590802201048.

- Roy, I. 2016. “Emancipation as Social Equality.” Focaal 2016 (76): 15–30. doi:10.3167/fcl.2016.760102.

- Scott, J. C. 1998. Seeing like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. Yale: Yale University Press.

- Somers, M. R. 1993. “Citizenship and the Place of the Public Sphere: Law, Community, and Political Culture in the Transition to Democracy.” American Sociological Review 58 (5): 587. doi:10.2307/2096277.

- Somers, M. R. 2008. Genealogies of Citizenship: Markets, Statelessness and the Right to Have Rights. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stack, T. 2012. Knowing History in Mexico: An Ethnography of Citizenship. Alberquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Telles, V. D. S., and D. V. Hirata. 2007. “Cidade e Práticas Urbanas: Nas Fronteiras Incertas Entre o Ilegal, o Informal e o Ilícito.” Estudos Avançados 21 (61): 1730–0191. doi:10.1590/S0103-40142007000300012.

- Vrasti, W., and S. Dayal. 2016. “Cityzenship: Rightful Presence and the Urban Commons.” Citizenship Studies 20 (8): 994–1011. doi:10.1080/13621025.2016.1229196.

- Wilmer, S. E. 2012. “Playing with Citizenship: NSK and Janez Janša.” Citizenship Studies 16 (5–6): 827–838. doi:10.1080/13621025.2012.698513.

- Zigon, J. 2018. A War on People: Drug User Politics and A New Ethics of Community. California: University of California Press.