ABSTRACT

This article reflects on the potential and limitations of global citizenship as a concept by which to analyse the politics of precarious migration and develops a novel methodology by which to generate an inventory of migratory claims. It focuses specifically on migratory claims-making in the context of externalisation, whereby proliferating actants and complex practices of cross-border control render accountability for harm increasingly obscure. Emphasising the importance of centring the claims of people with lived experiences of precarious migration in the analysis of the politics of migration, the article develops an analytical framework that includes implicit and indirect as well as explicit and direct claims to rights, belonging and accountability. The significance of such a framework is explored through an engagement with the testimonies of people crossing the Mediterranean from the Middle East and Africa during 2015–2016. Reflecting on the value as well as the problems of interpreting migratory claims through the lens of global citizenship, the article suggests that the concept should neither be disregarded nor reified in analyses of the politics of precarious migration.

Introduction

The claims of people with lived experiences of precarious migration are critical to the analysis the politics of migration: ‘I want safety’; ‘Open a route’; ‘We expect to be treated humanely’ (cited in Squire et al. Citation2021). Such demands to protection, freedom, equality, and humanity raise urgent questions about accountability, rights and belonging, yet are often overlooked because migrants are rarely considered as political subjects and authors of their own claims (Johnson Citation2016). Even where the political subjectivity of people migrating has been at the forefront, concerns regarding citizenship as a manifestation of sovereignty have led many scholars to attend to spaces ‘below the radar of existing political structures’ rather than to focus on migratory claims-making (Papadopoulos and Tsianos Citation2013; see also Hindess Citation1998). While exploring the claims of people with lived experience of precarious migration is on the one hand pressing, on the other hand careful consideration is thus required in engaging with such claims.

This article seeks to advance political reflection on migratory claims by interrogating global citizenship ‘in the making’ as an analytical framework. The concept of global citizenship ‘in the making’ is engaged here both to highlight the emergent quality of political subjectivity through acts of struggle (Isin Citation2001, Citation2012), as well as to draw attention to the generative ambivalence of migratory claims (McNevin Citation2012). That is, global citizenship is approached not so much as a manifestation of sovereignty or state power, but as a form of struggle that emerges in the context of existing relations of power. The article reflects on the value as well as the problems of interpreting migratory claims through the lens of global citizenship, to suggest that the concept should neither be disregarded nor reified in the analysis of the politics of precarious migration. Rather than imposing global citizenship as a homogenising interpretive lens, the article thus also reflects on the importance of an abolitionist framework for the analysis of migratory claims (e.g. Bradley and de Noronha Citation2022; Tazzioli and De Genova, Citation2023).

The argument developed in this article is grounded in an engagement with a counter-archive of migratory testimonies that was generated during 2015–2016 as part of the Crossing the Mediterranean Sea by Boat (CTM) project. CTM focused on the lived experiences and negotiations of the European policy agenda by people ‘on the move’, with interviews focusing on questions surrounding the migratory journey, reception experiences, expectations, and aspirations. The research team interviewed 271 people in Germany, Italy, Malta and Turkey, all of whom were selected as they had migrated – or were planning to migrate – across the Mediterranean Sea by boat. The first phase of the research was completed between September and November 2015 and involved 136 qualitative semi-structured interviews with a total of 139 participants at three island arrival sites: Kos, Malta and Sicily.Footnote1 The second phase of the research was completed during May–July 2016 and involved a further 121 interviews with a total of 132 participants at four urban sites: Athens, Berlin, Istanbul and Rome (Squire et al. Citation2017).

What became apparent in the process of examining the impact of policy developments on lived experiences of migration through the CTM project was that such experiences also generated a powerful range of demands or claims on the part of people migrating. By claims, I refer to appeals or demands that actually or potentially ‘affect the interests or integrity of the claimants and/or other collective actors’ (Koopmans et al. Citation2005, 24). These are embedded in established power dynamics, which create barriers to, as well as opportunities for, the recognition of claims by key ‘respondents’ (Bloemraad Citation2018). The claims that form the focus of this article were advanced in the context of a policy agenda focused on the ‘deterrence’ of migration (Squire et al. Citation2021). This agenda not only rendered reception or arrival conditions in Europe dire but was also implicated in deteriorating conditions beyond EU territory through the ‘externalisation’ of border controls to third states and the high seas (Cobarrubias et al. Citation2023). The claims arising through the research process in this regard were (more or less directly) addressed to respondents from diverse authorities across multiple sites (Squire Citation2021, Citation2022).

The CTM project was not originally designed to focus in detail on migratory claims-making. However, we quickly realised as a research team that these were important elements of our findings, hence in the second phase of the research we explicitly added a question about what research participants would want to convey to European policy makers or societies if they had the chance. The second-phase interviews also included context-specific questions, as our awareness deepened around key areas of concern. For example, those who had travelled to Italy via the ‘central Mediterranean route’ were asked about the conditions in Libya. Those who had travelled to Athens and Berlin through the ‘eastern Mediterranean route’ – and those in Istanbul who were planning to do so – were asked about their knowledge of the March 2016 EU-Turkey ‘deal’, which was designed to prevent arrival to the EU. These various questions generated a wide range of demands that were more or less explicit, the detail of which this article further explores.Footnote2

It is based on an appreciation of the importance of the migratory claims our research uncovered that this article seeks to open reflection on the potential and limitations of global citizenship ‘in the making’. To be clear, the analysis here does not seek to suggest that people with lived experience of precarious migration identify as ‘global citizens’. Rather, the aim is to interrogate and question the potential and limits of global citizenship ‘in the making’ as an analytical lens by which to interpret migratory claims. The value of such a concept for analysing the politics of precarious migration is considered specifically in contexts characterised by a drive toward the externalisation of migration control policies beyond the boundaries of the territorial state. In such contexts, proliferating actants and complex practices of cross-border control render accountability for harm increasingly obscure. Reflecting this, we found migratory claims to be broad-reaching in the sense that they extended far beyond our focus on the European policy agenda.

Global citizenship ‘in the making’

The concept of global citizenship has been articulated in various ways: as an individual moral status forming the grounds for human rights (Cabrera Citation2010), as membership of a global civil society (Tan Citation2017), and as a form of participation within world government or global cosmopolitan democracy (Archibugi and Held Citation2011; Goodin Citation2013). While scholarship within the field often engages normative cosmopolitan theory to advance a case for the benefits of global citizenship, this article instead approaches global citizenship ‘in the making’ as an expansive and multi-dimensional analytical framework. That is, global citizenship ‘in the making’ is engaged here to analyse the ways that citizenship is ‘rearticulated’ in practice through the overlap of its various dimensions across multiple sites (Staeheli Citation2010, 393). Rather than approaching ‘global citizenship’ as an overarching universal concept or as signalling the shift toward rights and belonging at a new level, an analysis of global citizenship ‘in the making’ thus demands an openness to claims to rights, belonging and accountability that cut across and through traditional ‘scales’ of reference (e.g. the national, the local, the global). It also, importantly, requires that attention is paid to claims that potentially exceed the scope of its definition, such as through appeals to abolitionism.

So why engage the concept of global citizenship over an alternative such as cosmopolitan citizenship? The aim of this article is not to advance a normative theory of citizenship, but rather to test a grounded analytics of global citizenship ‘in the making’ through exploration of the ways that migratory claims potentially generate emergent forms of accountability, rights and belonging (cf. Nyers and Rygiel Citation2012). As such, the analysis developed here resonates with scholarship of cosmopolitan citizenship ‘from below’ (Baban and Rygiel Citation2014; Caraus Citation2018; Topak Citation2017). Nevertheless, this article also focuses more squarely on the spatial dimensions of claims-making (cf. Isin Citation2017). It engages ‘the global’ specifically in the context of processes of externalisation, whereby migration controls are extended beyond state territorial borders in the attempt to deter or impede migratory journeys. Processes of externalisation reflect a limited commitment to human rights (Schmid Citation2022). They also produce precarities at various stages of the migratory journey, whether through the extension of visa controls and carrier sanctions (Vries et al. Citation2019), intensified border security mechanisms and forms of ‘remote control’ (Jones Citation2016; Zolberg cited in FitzGerald Citation2020, 4) or the rolling out of control measures across a range of everyday situations (Rigo Citation2011). Engaging global citizenship as a conceptual lens in the context of externalisation thus provides an opportunity to explore the claims of those most directly affected by the complexity of controls that cut through and across borders – that is, people with lived experience of precarious migration themselves.

The relevance of global citizenship ‘in the making’ as a framework for the analysis of claims advanced by people with lived experience of precarious migration is perhaps evident if we consider how externalisation is bound up with a complexification of the sites and actors involved in governing migration. Over recent years, migration management has become increasingly populated by international organisations (Geiger and Pécoud Citation2010; Lavenex Citation2016) and transregional partnerships (Betts Citation2011; Kunz, Sandra, and Marion Citation2011). Scholars of polycentric governance have highlighted a range of formal and informal actors involved in governing migration beyond state borders (Koinova Citation2022). The complexity of governing practices and the fracturing of authority or lines of responsibility in this regard generates what democratic theorists describe as a ‘crisis of accountability’ (Thompson Citation1999). Yet this crisis of accountability does not simply arise because state-based mechanisms of accountability are inaccessible to migrants (Abizadeh Citation2008). So, also, does this arise because externalisation produces a messy range of practices and actants that cannot be fixed to a particular scale of analysis, thus eliding answerability (Brachet Citation2016).

The demands of people with lived experience of precarious migration to answerability for precarity or harm are critical in shedding light on how a form of global citizenship ‘in the making’ potentially emerges from the development of externalised practices of governing migration. Nevertheless, although there has been an increasing emphasis within migration studies over recent years regarding the importance of bringing migrant perspectives to the forefront of analysis in situations of precarity, the literature in this area remains somewhat limited. Much of the work within the field has focused on the aspirations that feature in the decision to migrate (Carling and Collins Citation2018), or on context-specific factors that shape migrant perceptions at different locations (Crawley and Hagen-Zanker Citation2019). Less work has been carried out on migratory claims-making in situations of precarity, despite appeals that migration studies scholars pay attention to ‘migrant agency’ (Anderson and Ruhs Citation2010), and despite recognition of the need to challenge the stereotypes through which migrants are so-often perceived as either ‘victims or villains’ (Chouliaraki Citation2015; Little and Vaughan-Williams Citation2017). Engaging global citizenship ‘in the making’ as a framework of analysis potentially redresses this oversight, since it is precisely grounded in the claims of people migrating in precarious situations.

Generating an inventory of migratory claims

Migratory claims-making has become a significant field of study at the intersections of citizenship and migration studies over recent years (e.g. Koopmans et al. Citation2005). Such works have made important advances in analysing the ways in which institutional political opportunity structures facilitate and impede the advancement of claims by immigrant communities (Giugni and Passy Citation2004). Furthermore, work in this area has also drawn attention to the importance of studying processes of recognition and non-recognition on the part of respondents to whom claims are directly or indirectly addressed (Bloemraad Citation2018). Notably, however, such works have focused primarily on claims advanced by immigrant groups that have a relatively established position within an established citizenship regime, and that have a clear identity forged through the migration process (e.g. as members of diasporic or ‘minority’ communities). Indeed, such a focus may be an inevitable implication of an institutional analysis of political opportunity structures and processes of (non)recognition that centre path dependence, since actors that do not hold a position within an already-established regime or whose claims are not fixed to an established identity appear to be necessarily marginalised as claimants within this frame of analysis (e.g. see Koopmans, Michalowski, and Waibel Citation2012). From such a perspective, the claims of people migrating in precarious situations, whose status, location, and positionality do not fit into established institutional or identity-based frameworks, are often disregarded.

Although the analysis of migratory claims in situations of precarity has been relatively limited in comparison to works on the claims of ‘minority’ communities (e.g. Koopmans and Statham Citation2003), as well as in comparison to works on migrant aspirations (e.g. Collins and Carling Citation2019), recent scholarship on migrant activism nevertheless provides important insights into the politics of precarious migration (e.g. McNevin Citation2011; Nyers and Rygiel Citation2012; Tyler and Marciniak Citation2013; Ataç, Rygiel, and Stierl Citation2016). Such works do not take as a starting point the institutional framework of the nation state or even its potential transnational development (Koopmans et al. Citation2005). Nor do such works focus on the decision-making of people on the move with the aim of making sense of migratory drivers (Collins and Carling Citation2019). Rather, scholars of migrant activism build understanding of the ways in which political subjectivity ‘precedes’ legal status (Nyers Citation2015), to explore how collective actions and protests disrupt exclusionary citizenship and border regimes (e.g. McGregor Citation2011; Monforte Citation2016). Where the concept of citizenship is engaged it is often with reference to the ‘acts of citizenship’ literature, whereby subjects constitute citizenship through a process of enactment instead of through the achievement of status (Isin and Nielsen Citation2008). Beyond a focus on visible ‘acts of demonstration’ or protest (Walters Citation2008), scholars of migrant activism also explore everyday acts of resistance (El-Bialy and Mulay Citation2020), mundane collective activities (Kallio, Meier, and Häkli Citation2021) and intimate spaces of encounter (Monforte and Steinhilper Citation2023). This demands an appreciation of claims that ‘potentially affect the interests or integrity of the claimants and/or other collective actors’ (Koopmans et al. Citation2005, 24), yet in terms that go beyond a reductive account of what counts as a claim.

How then can we engage claims-making as an analytical frame without oversight of everyday and intimate forms of resistance, which are often enacted in implicit and indirect terms rather than being demanded explicitly and directly? In his analysis of representation and claims-making, Saward (Citation2010) draws attention to variations not only in the content or types of demands advanced, but also in their various forms or modes of expression. He suggests that, since some claims are more verbal, conscious and focused than others, we might analyse different forms of claims-making along the continuums of implicit-explicit demands. Saward’s intervention is critical here in moving the analysis of claims beyond more visible forms of protest and verbally articulated demands, toward an appreciation of everyday and mundane acts as integral to the analysis of claims-making. Claims in this regard may not be articulated openly and may even be unconsciously enacted or presented in generalised terms in some contexts. However, this is not to disregard these as demands nor is it to suggest that unconscious, non-verbal and general claims will necessarily remain as such in all cases. The work required of the analyst in this regard is to find ways to render the interpretation of claims more explicit, without imposing an interpretive framework or seeking to ‘speak for’ those with lived experiences of precarious migration (see Qasmiyeh Citation2019).

Drawing on a conceptualisation of claims-making as implicit and indirect, as well as explicit and direct, we can begin to unpack the ways in which people on the move in precarious situations advance a range of different types of claims, in varied forms. Examples of migrant claims include conscious and focused verbal appeals, such as the demands of Sudanese refugees in Egypt for the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) to stand accountable for the failures of protection (Moulin and Nyers Citation2007), or the demands of El Salvadorans in the USA to the right of asylum (Coutin Citation2005). Examples may also include more generalised, non-verbal claims, such as the implicit appeal to the right to free movement enacted by those undertaking journeys without authorisation (Stierl Citation2019). By exploring multiple types and forms of claims advanced by people living and migrating under precarious conditions, we might begin to build an inventory of claims that challenge the forms of precarity conditioned by processes of externalisation, and that generate alternative political horizons of accountability, rights and belonging. It is thus to an analysis of demands advanced in the context of externalisation and their various forms that the analysis will now turn.

Claims to global citizenship?

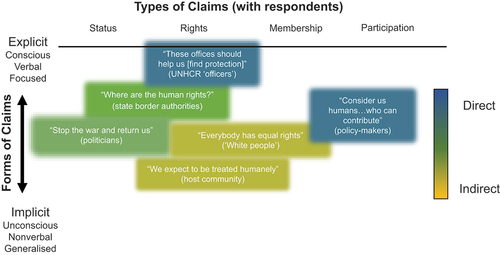

‘Where are the human rights, when someone escapes war and you shut down all the doors to his face?’ (Syrian woman, Kos); ‘White people normally go to Nigeria’ … ‘Everybody has equal rights’ (Nigerian women, Rome); ‘Back in time, we used to have Europeans as refugees…We expect to be treated humanely in Europe’ (Iraqi man, Kos); ‘Stop the war and return us’ (Syrian woman, Athens); ‘Consider us as humans, humans who can contribute not only to the economy but also in policy making’ (Ethiopian man, Malta); ‘They say that there is relocation, let them prove it. [That] there is protection, let them prove it … These offices should help us’ (Syrian woman, Istanbul). These are some of the testimonies arising from the CTM project, which exposed a plethora of relatively explicit claims to human rights (Syrian woman, Kos), to be provided with protection (Syrian woman, Istanbul), to equal rights (Nigerian woman, Rome), to humane treatment (Iraqi man, Kos) and to the opportunity to participate in economic and policy making (Ethiopian man, Malta). The analysis also exposed more implicit claims, such as the right to live in peace (Syrian woman, Athens). Responsibility for the harms associated with precarious migration were directly attributed to key respondents in some cases (e.g. to officers responsible for resettlement claims) and indirectly referred to in others (e.g. to host communities and ‘White people’). Indicative of the importance both of everyday forms of struggle (e.g. contributing to the economy), as well as of more spectacular forms of struggle (e.g. escaping war), even a cursory analysis of these claims appears to suggest that an alternative politics of accountability, rights and belonging may be ‘in the making’ on the basis of migratory struggles over externalised controls.

The testimonies above have been chosen for further discussion here because they are broadly representative of some of the most explicit claims that we found in the CTM research. The choice of quotes is by no means exhaustive, but for the purposes of this article they provide important insights into the range of ways in which people with lived experiences of precarious migration ‘speak back’ to the precarities and harms through which they have had to live. It is important to give some context to such claims, to understand in what terms they were advanced and in what ways they relate to the context of externalisation. For example, the claim to human rights by the Syrian woman in Kos speaks to the situation she and others had experienced on arriving to the Greek island in 2015, whereby people had to sleep in tents on the street while awaiting permission to travel to the mainland to make an asylum claim and/or to travel onward within Europe. The sense of doors ‘shutting’ also comes through in the testimony of the Iraqi man in Kos, who expresses his expectation of protection and appeals to humane treatment. The Syrian woman in Istanbul speaks most directly to the ways in which externalised controls prevent access to European territory. She and her sister and elderly mother had been waiting to be resettled by the UNHCR due to the dangers of travelling by boat, but had been waiting to reunify with family members in Sweden for many months. Many of the quotes point to the ways in which the logic of externalisation becomes embedded within the EU territory itself, creating ‘periphery’ states where people are denied what the Nigerian woman in Rome refers to as ‘equal rights’, or what the Ethiopian man in Malta refers to as appreciation of refugees or migrants as ‘humans’ who can contribute to society. In this vein, the Syrian woman in Athens also speaks out in frustration regarding the difficulties of reunifying with family members and the closure of borders to northern Europe, appealing to global leaders for answerability to the Syrian conflict.

These claims are diverse and can of course be interpreted in various ways. Yet in their multiple dimensions they also reflect what might be called global citizenship ‘in the making’: human or equal rights, membership of a wider community that provides protection to those in need, the ability to participate in society and to live in peace … To begin to make sense of this, starts the work of mapping some of the different types of claims advanced by people with lived experience of precarious migration. These are situated along the horizontal axis in terms of the multiple dimensions of global citizenship outlined earlier: claims to a legal status, to human and refugee rights, and to membership of or participation within a broader political community. The claims introduced above often do not fit neatly into one of these categories in a singular sense, but rather overlap several - and even potentially exceed - the categories (such as in the references to humanity, peace and equality). Moreover, the claims do not fit neatly into the ‘global’ as a ‘scale’ of analysis, often cutting across multiple ‘levels’ such as in the appeals to protection or to having the opportunity to return to a home country. What a preliminary analysis therefore suggests is that, while migratory claims often appeal to categories associated with (global) citizenship, they do so in terms that are suggestive of its multi-dimensional and emergent formation, as well as in terms that can also extend beyond the scope of (global) citizenship itself. As an analytical framework and conceptual lens, global citizenship ‘in the making’ can thus be a helpful way to examine the political significance of migratory claims that emerge within contexts characterised by externalised controls, but it is not intended to be an exhaustive or exclusive approach.

also begins the work of mapping some of the different forms of claims that are generated by lived experiences of precarious migration. It focuses vertically on those which operate along a continuum of explicit-implicit claims, to refer to the degree of precision or overtness in the expression of the content of each claim. The continuums of conscious-unconscious, verbal-nonverbal and focused-generalised claims are closely aligned to the explicit-implicit, and hence are also represented along the vertical axis (see Saward Citation2010). also shows how each claim more or less directly identifies a ‘respondent’ who is answerable to the claimant. This is represented through colour-coding, with the darker colour representing more direct claims and the lighter colour representing those that lie toward the indirect end of the continuum. Claims are thus located on the continuums of explicit-implicit and direct-indirect claims dependent on their content as well as on the directness of their identification of respondents (which are included in brackets).

Striking in the types and forms of claims charted in are the ways in which answerability for precarity and harm is demanded from multiple respondents (e.g. host communities, border authorities and international organisations), as well as in terms that point to everyday as well as institutionalised forms of control (e.g. inhumane treatment and the denial of refugee rights). Of course, this initial analysis of claims-making only provides only a snapshot of how we might begin to generate an inventory of claims that challenge the proliferating actants and complex practices of cross-border control embedded through processes of externalisation. Nevertheless, a key implication of this discussion is that, by mapping different types and forms of claims, we begin to move beyond binary analyses of spectacular forms of protest politics and accretive forms of everyday politics, to develop a more broad-reaching framework by which to analyse practices of resistance and activism by people with lived experience of precarious migration. Rather than simply involving a categorisation of claims, however, an inventory of migratory claims requires further in-depth qualitative research and careful reflections with people in situations of precarity and displacement to clarify the political significance and horizons toward which such claims are oriented. That such claims can be unified toward a singular horizon or that global citizenship is necessarily the most desirable horizon to aim towards politically is far from evident, as deeper engagement with the claims of people who have lived experience of precarious migration indicates.

Claims to abolition?

Developing an inventory of migratory claims that centres the claims of people on the move in precarious situations is not a simple process and cannot be reduced to a process of categorisation based on dominant classification systems. The risk of imposing a homogenised view is a key danger in advancing global citizenship ‘in the making’ as a framework of analysis, particularly if meaningful interpretive engagement with those advancing such claims is not integral to the process or an openness to alternative interpretive frameworks is lacking. Developing such an approach in complex situations of precarity and displacement remains a challenge both practically and politically – particularly if an analysis of migratory claims is to avoid engraining new forms of extractivism and exploitation (see Squire et al. Citationforthcoming). The inventory envisioned here thus requires sustained, participatory, in-depth qualitative and dialogical work, in terms that exceed the scope of the research on which this article is based. Moreover, the slower reflections and continued collaborations that such work requires is all-the-more challenging given that research funding structures often do not facilitate longer-standing engagements, and contexts of externalisation often preclude longer-standing engagements with people ‘on the move’. This is not to say that such work cannot be carried out, but it is to introduce a note of caution in the development of global citizenship ‘in the making’ as a lens of analysis, as well as in any effort to generate an inventory of claims-making in the field of precarious migration.

A closer reading of some of the claims advanced by people interviewed by the CTM team guards against a reductive interpretation of migratory claims as fully encapsulated by the concept of global citizenship. In some respects, the claims advanced may be better understood in terms of the abolition of structures of power. Indeed, I have highlighted elsewhere how the act of precarious migration can also be interpreted as a demand for the abolition of militaristic and colonial structures and institutions (Squire Citation2021). For example, appeals to the abolition of militarism are evident in the testimonies of several Syrian men in Berlin, who described their escape from Syria in terms of a refusal to kill: ‘I don’t kill anyone’; ‘I didn’t want to carry the blood in my name’; ‘I don’t want to kill anybody’. For a woman interviewed in Istanbul, this anti-militarism appears to slide into a politics of anti-colonialism in reflection on the ‘connected’ trajectories of coloniality and violence (see Bhambra Citation2014): ‘Who is responsible [for the bloodshed in Syria]? It is the politics of the powerful countries … The powerful countries are watching us. They are silent. International silence’. Recurring colonial dynamics are also explicitly highlighted as problematic by a man from the Ivory Coast who was interviewed in Malta: ‘those who colonise us they have a lot of organisations, or [organisations run] by … Europe[an countries] to cooperate with our government in my country’. Rich and powerful countries, a world that remains silent, organisations with connections in Europe, African governments: these are just some of the ‘respondents’ directly or indirectly identified here as accountable for lived experiences of precarious migration.

So, of what significance are abolitionist claims in the context of externalisation specifically, whereby proliferating actants and complex practices of cross-border control render accountability for harm increasingly obscure? It is here that I would like to return to the quote in the last sub-section by the woman from Nigeria, and the demand to ‘equal rights’. Interviewed alongside two other Nigerian women in Rome in 2016, the claim to equal rights was presented in response to the interviewer asking the group whether they believed they had the right to enter the Italy and the European Union from Libya, through which they passed. One of the other women replied that she did believe they had the right to enter, because: ‘White people normally go to Nigeria, they are safe, they are okay. I know that very well. So everybody I want, you know, God created everybody’. Following this, the woman appealing to equal rights went on to say: ‘So it is the same. Everybody is free. You are free to go to Nigeria, there is your choice. So, your push allows us enter Italy freely without no problem, that is what we want’. While this quote may be interpreted as a generalised claim to universal rights and freedoms, it also involves a rejection of racially unjust border controls (see also Achiume Citation2017). Indeed, the hierarchical application of rights and freedoms is explicitly identified by the woman’s interlocutor as racially constructed – enjoyed by ‘White people’ but not by people from Nigeria. As well as – or beyond – an act of global citizenship, such a claim may thus also interpreted as an act of desertion or engaged withdrawal (Squire Citation2015a): one that demands an abolition of the policing of the ‘Black Mediterranean’ (Saucier and Woods Citation2014; Danewid Citation2017), and that generates alternatives to processes of ‘organised abandonment’ (Gilmore Citation2015).

A cautionary conclusion

In reflecting on the potential as well as the limitations of interpreting migratory claims through the lens of global citizenship, the analysis in this article has suggested that the concept should neither be disregarded nor reified through the analysis of the politics of precarious migration. As an expansive conceptual lens, embedded in the empirical analysis of migratory claims that are both explicit and implicit, direct and indirect, global citizenship ‘in the making’ provides a helpful analytical framework by which to generate an inventory of migrant claims. Importantly, it facilitates a move beyond the binary of spectacular versus incremental politics, while remaining grounded in the demands of people with lived experiences of precarious migration themselves. This is not to hold up global citizenship as a normative horizon, which would jar with the grounded analytical approach developed here as well as with the abolitionist interpretation that the analysis above indicates is integral to the politics of precarious migration. As well as avoiding the assumption that ‘migrant struggles are or ought to be struggles aimed at citizenship in its prevailing form’ (McNevin Citation2020, 551), caution is thus required regarding the assumption that citizenship in any form stands as the horizon for migrant struggles.

Despite this, the analysis in this article suggests that global citizenship ‘in the making’ is a generative framework by which to understand claims to answerability in the context of externalised control. The externalisation of migration management has bought with it mobility partnerships, migration cooperation instruments and the linkage of development aid and border security measures in terms that dilute accountability for harm (Brachet Citation2016; Zanker and Altrogge Citation2017). It has also seen the moblisation of environmental forces in terms that divert responsibility for the harms generated by migration control (Doty Citation2011; Squire Citation2015b; Sundberg Citation2011). Externalised controls in this respect involve slow as well as spectacular forms of violence, which are enacted by multiple actants or assemblages across fissured spaces (Davis, Isakjee, and Dhesi Citation2017; Schindel Citation2022). Despite the fracturing of conventional conceptions of spatial order and political authority, the messy miss-match of practices and actants are nevertheless called into account by people with lived experiences of precarity. Generating a detailed inventory of such claims in terms that are expansive in scope as well as precise in their analysis is critical in this context. So also is the analysis of the (non)recognition of demands by the diverse range of ‘respondents’ who are identified as culpable for experiences of precarity and harm – including citizens themselves. This article thus identifies these as pressing areas of further enquiry.

‘Listen [to] us’ (Sudanese man in Rome). ‘We just want our voice to be heard in the world’ (Syrian woman in Kos). Listening takes many forms and requires time as well as ongoing engagement to find new ways of being and acting together (Bassel Citation2017). The findings in this article highlight the potential benefits of a detailed inventory of migratory claims, the necessity of a fine-grained analysis of various types and forms of claims, the importance of a dialogical method in order that the content and expression of claims can be explored with those migrating under precarious conditions, as well as the criticality of maintaining cautionary openness regarding global citizenship ‘in the making’ as an analytical framework. Yet several further notes of caution are worth emphasising. First, it is important that the claims of people on the move are not examined in isolation from those of the wider communities within which people live and through which people migrate (e.g. Tazzioli Citation2023). Subversive struggles for citizenship, like abolitionist movements, bring people together in shared struggles rather than dividing them in the face of precarity and harm. Separating migrants from citizens can be self-defeating politically as well as misplaced analytically. Related to this, it is important not to reduce the politics and subjectivity of migrants to claims and experiences of precarity. This not only risks essentialising victimhood, but also can erase the rich ‘pluriversal’ subjectivity of people on the move (Yemane and Yohannes Citation2023). Listening to the claims of those with lived experience of precarious migration in the context of externalised control thus requires care and attention to the potential harms that such analysis may also engender. It is with this in mind that the conceptual lens of global citizenship ‘in the making’ is advanced here – with caution, as well as with commitment and attentiveness.

Acknowledgments

This article draws on the findings of a research project funded by the UK Economic and Social Research Council, Crossing the Mediterranean Sea by Boat: Mapping and Documenting Migratory Journeys and Experiences, grant number ES/N013646/1. This was a large collaborative project, and sincere thanks are extended to the whole research team including Co-I’s, Angeliki Dimitriadi, Maria Pisani, Dallal Stevens, Nick Vaughan-Williams and the project Research Fellow Nina Perkowski; research assistants supporting with interviews, Saleh Ahmed, Skerlida Agoli, Alba Cauchi, Sarah Mallia, Mario Gerada, Vasiliki Touhouliotis and Emanuela dal Zotto. Sincere thanks are also extended to our translators and transcribers and, not least, to the many research participants involved in the project. I would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and the editors of the journal for their very helpful comments on an earlier version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Difficulties in recruiting research participants in Malta due to reduced arrivals resulting from an ‘agreement’ with Italy during the time-period of our research led to some of the interviews being carried out at this site between December 2015 and March 2016.

2. Interviews were directly undertaken in English where possible, with the working languages of our research team (Arabic, German, Italian and French) also used as appropriate. However, we also worked directly with translators for a large number of our interviews. All interviews were transcribed into English in full prior to the process of analysis, with the majority of interviews recorded directly. The transcripts of those that were not recorded were based on extensive notes that were written up in full by the interviewer. The use of translators of course raises important questions about the accuracy of translating claims and particularly about the feasibility of interpreting claims that were less explicit and direct. This remains an aspect of the analysis that cannot be addressed in retrospect here, but such considerations clearly require careful thinking for future work in this area.

References

- Abizadeh, A. 2008. “Democratic Theory and Border Coercion.” Political Theory 36 (1): 37–65. doi:10.1177/0090591707310090.

- Achiume, E. T. 2017. “Reimagining International Law for Global Migration: Migration as Decolonisation?” AJIL Unbound 111: 142–146. doi:10.1017/aju.2017.48.

- Anderson, B., and M. Ruhs. 2010. “Researching Illegality and Labour Migration.” Population, Space and Place 16 (3): 175–179. doi:10.1002/psp.594.

- Archibugi, D., and D. Held. 2011. “Cosmopolitan Democracy: Paths and Agents.” Ethics and International Affairs 25 (4): 433–461. doi:10.1017/S0892679411000360.

- Ataç, I., K. Rygiel, and M. Stierl. 2016. “Introduction: The Contentious Politics of Refugee and Migrant Protest and Solidarity Movements: Remaking Citizenship from the Margins.” Citizenship Studies 20 (5): 527–544. doi:10.1080/13621025.2016.1182681.

- Baban, F., and K. Rygiel. 2014. “Snapshots from the Margins: Transgressive Cosmopolitanisms in Europe.” European Journal of Social Theory 17 (4): 461–478. doi:10.1177/1368431013520386.

- Bassel, L. 2017. The Politics of Listening: Possibilities and Challenges for Democratic Life. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Betts, A. 2011. “The Global Governance of Migration and the Role of Trans-Regionalism.” In Multilayered Migration Governance: The Promise of Partnership, edited by R. Kunz, S. Lavanex, and M. Panizzon, 23–45. New York: Taylor and Francis.

- Bhambra, G. 2014. Connected Sociologies. London: Bloomsbury.

- Bloemraad, I. 2018. “Theorising the Power of Citizenship as Claims-Making.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (1): 4–26. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1396108.

- Brachet, J. 2016. “Policing the Desert: The IOM in Libya Beyond War and Peace.” Antipode 48 (2): 272–292. doi:10.1111/anti.12176.

- Bradley, G. M., and L. de Noronha. 2022. Against Borders: The Case for Abolition. London: Verso.

- Cabrera, L. 2010. The Practice of Global Citizenship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Caraus, T. 2018. “Migrant Protests as Acts of Cosmopolitan Citizenship.” Citizenship Studies 22 (8): 791–809. doi:10.1080/13621025.2018.1530194.

- Carling, J., and F. Collins. 2018. “Aspiration, Desire and the Drivers of Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6): 909–926. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384134.

- Chouliaraki, L. 2015. The Ironic Spectator: Solidarity in the Age of Post-Humanitarianism. Bristol: Polity Press.

- Cobarrubias, S., P. Cuttitta, M. Casas-Cortés, M. Lemberg-Pedersen, E. Qadim, I. Nora, F. Beste, G. Shoshana, Heller, and C. Caterina. 2023. “Interventions on the Concept of Externalization in Migration and Border Studies.” Political Geography 105 (3): 102911. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2023.102911.

- Collins, F., and J. Carling, eds. 2019. Aspiration, Desire and the Drivers of Migration. London: Routledge.

- Coutin, S. B. 2005. “Contesting Criminality: Illegal Immigration and the Spatialisation of Legality.” Theoretical Criminology 9 (1): 5–33. doi:10.1177/1362480605046658.

- Crawley, H., and J. Hagen-Zanker. 2019. “Deciding Where to Go: Policies and Perceptions Shaping Destination Preferences.” International Migration 57 (1): 20–35. doi:10.1111/imig.12537.

- Danewid, I. 2017. “White Innocence in the Black Mediterranean: Hospitality and the Erasure of History.” Third World Quarterly 38 (7): 1674–1689. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1331123.

- Davis, T., A. Isakjee, and S. Dhesi. 2017. “Violent Inaction: The Necropolitical Experience of Refugees in Europe.” Antipode 49 (5): 1263–1284. doi:10.1111/anti.12325.

- Doty, R. L. 2011. “Bare Life: Border Crossing Deaths and Spaces of Moral Alibi.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29 (4): 599–612. doi:10.1068/d3110.

- El-Bialy, R., and S. Mulay. 2020. “Microagression and Everyday Resistance in Narratives of Refugee Resettlement.” Migration Studies 8 (3): 356–381. doi:10.1093/migration/mny041.

- FitzGerald, D. 2020. “Remote Control of Migration: Theorising Territoriality, Shared Coercion, and Deterrence.” Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 46 (1): 4–22.

- Geiger, M., and A. Pécoud, eds. 2010. The Politics of International Migration. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Gilmore, R. W. 2015. “Organised Abandonment and Organized Violence: Devolution and the Police.” US Presidential Chair in Feminist Critical Race and Ethnic Studies Lecture, UC Santa Cruz. 9 November 2015. https://thi.ucsc.edu/event/ruth-wilson-gilmore-2/.

- Giugni, M., and F. Passy. 2004. “Migrant Mobilisation Between Political Institutions and Citizenship Regimes: A Comparison of France and Switzerland.” European Journal of Political Research 43 (1): 51–82. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2004.00145.x.

- Goodin, R. E. 2013. “World Government is Here!” In Varieties of Sovereignty and Citizenship, edited by S. R. Ben-Porath and R. M. Smith, 149–165. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press.

- Hindess, B. 1998. “Divide and Rule: The International Character of Modern Citizenship.” European Journal of Social Theory 1 (1): 57–70. doi:10.1177/136843198001001005.

- Isin, E. 2001. Being Political: Genealogies of Citizenship. Minneapolis: Minnesota Press.

- Isin, E. 2012. Citizens without Frontiers. London: Bloomsbury.

- Isin, E. 2017. “Enacting International Citizenship.” In International Political Sociology: Transversal Lines, edited by T. Basaran, D. Bigo, E.-P. Guittet, and B. J. Rob. Walker. London: Routledge.

- Isin, E., and G. M. Nielsen. 2008. Acts of Citizenship. London: Zed Books.

- Johnson, H. L. 2016. “Narrating Entanglements: Rethinking the Global/Local Divide in Ethnographic Migration Research.” International Political Sociology 10 (4): 383–397. doi:10.1093/ips/olw021.

- Jones, R. 2016. Violent Borders: Refugees and the Right to Move. London: Verso.

- Kallio, K. P., I. Meier, and J. Häkli. 2021. “Radical Hope in Asylum Seeking: Political Agency Beyond Linear Temporality.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (17): 4006–4022. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1764344.

- Koinova, M. 2022. “Polycentric Governance of Transit Migration: A Relational Perspective from the Balkans and the Middle East.” Review of International Studies 48 (3): 461–483. doi:10.1017/S0260210521000693.

- Koopmans, R., I. Michalowski, and S. Waibel. 2012. “Citizenship Rights for Immigrants: National Political Processes and Cross-National Convergence in Western Europe, 1980-2008.” American Journal of Sociology 117 (4): 1202–1245. doi:10.1086/662707.

- Koopmans, R., and P. Statham. 2003. “How National Citizenship Shapes Transnationalism: Minority Claims-Making in German, Great Britain and the Netherlands.” In Towards Assimilation and Citizenship: Immigrants in Liberal Nation-States, edited by C. Joppke and E. Morawska, 195–238. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Koopmans, R., P. Statham, M. Giugni, and F. Passy. 2005. Contested Citizenship: Immigration and Cultural Diversity in Europe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Kunz, R., L. Sandra, and P. Marion, eds. 2011. Multilayered Migration Governance: The Promise of Partnership. New York: Taylor and Francis.

- Lavenex, S. 2016. “Multilevelling EU External Governance: The Role of International Organisations in the Diffusion of EU Migration Policies.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (4): 554–570. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1102047.

- Little, A., and N. Vaughan-Williams. 2017. “Stopping Boats, Saving Lives, Securing Subjects: Humanitarian Borders in Australia and Europe.” European Journal of International Relations 23 (3): 533–566. doi:10.1177/1354066116661227.

- McGregor, J. 2011. “Contestations and Consequences of Deportability: Hunger Strikes and the Political Agency of Non-Citizens.” Citizenship Studies 15 (5): 597–611. doi:10.1080/13621025.2011.583791.

- McNevin, A. 2011. Contesting Citizenship: Irregular Migration and New Frontiers of the Political. New York: Columbia University Press.

- McNevin, A. 2012. “Ambivalence and Citizenship: Theorising the Political Claims of Irregular Migrants.” Millennium Journal of International Studies 41 (2): 182–200. doi:10.1177/0305829812463473.

- McNevin, A. 2020. “Time and the Figure of the Citizen.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 33 (4): 545–559. doi:10.1007/s10767-020-09358-4.

- Monforte, P. 2016. “The Border as a Space of Contention: The Spatial Strategies of Protest Against Border Controls in Europe.” Citizenship Studies 20 (3–4): 411–426. doi:10.1080/13621025.2015.1075471.

- Monforte, P., and E. Steinhilper. 2023. “Fragile Solidarities: Contestation and Ambiguity at European Borderzones.” doi:10.1093/jrs/fead038.

- Moulin, C., and P. Nyers. 2007. “We Live in a Country of UNHCR – Refugee Protests and Global Civil Society.” International Political Sociology 1 (4): 356–372. doi:10.1111/j.1749-5687.2007.00026.x.

- Nyers, P. 2015. “Migrant Citizenships and Autonomous Mobilities.” Migration, Mobility and Displacement 1 (1): 23–39. doi:10.18357/mmd11201513521.

- Nyers, P., and K. Rygiel, eds. 2012. Citizenship, Migrant Activism and the Politics of Movement. London: Routledge.

- Papadopoulos, D., and V. Tsianos. 2013. “After Citizenship: Autonomy of Migration, Organisational Ontology and Mobile Commons.” Citizenship Studies 17 (2): 178–196. doi:10.1080/13621025.2013.780736.

- Qasmiyeh, Y. M. 2019. “To Embroider the Voice with Its Own Needle.” Refugee Hosts Blog, (16 January 2019). Accessed on 30 April 2019 at https://refugeehosts.org/2019/01/16/to-embroider-the-voice-with-its-own-needle/.

- Rigo, E. 2011. “Citizens Despite Borders: Challenges to the Territorial Order of Europe.” In The Contested Politics of Mobility: Borderzones and Irregularity, edited by V. Squire, 199–215. London: Routledge.

- Saucier, P. K., and T. Woods. 2014. “Ex-Aqua: The Mediterranean Basin, Africans on the Move, and the Politics of Policing.” Theoria 61 (141): 55–75. doi:10.3167/th.2014.6114104.

- Saward, M. 2010. The Representative Claim. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schindel, E. 2022. “Death by ‘Nature’: The European Border Regime and the Spatial Production of Slow Violence.” Environment & Planning C Politics & Space 40 (2): 428–446. doi:10.1177/2399654419884948.

- Schmid, L. 2022. “Saving Migrants’ Basic Human Rights from Sovereign Rule.” American Political Science Review 116 (3): 954–967. doi:10.1017/S0003055422000028.

- Squire, V. 2015a. “Acts of Desertion: The Ambiguities of Abandonment and Renouncement Across the Sonoran Borderzone.” Antipode 47 (2): 500–516. doi:10.1111/anti.12118.

- Squire, V. 2015b. Post/Humanitarian Border Politics Between Mexico and the US: People, Places, Things. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Squire, V. 2021. “Unruly Migrations, Abolitionist Alternatives.” Behemoth 14 (3): 14–24.

- Squire, V. 2022. “Hidden Geographies of the ‘Mediterranean Migration Crisis.” Environment & Planning C Politics & Space 40 (5): 1048–1063. doi:10.1177/2399654420935904.

- Squire, V., Ọ. Àkànle, B. Jones, K. Logo, and J. Porto de Albuquerque. forthcoming. “Empowering Data Literacies in Displacement.” Journal of Humanitarian Affairs. Submitted to.

- Squire, V., A. Dimitriadi, N. Perkowski, M. Pisani, D. Stevens, and N. Vaughan-Williams 2017. Crossing the Mediterranean Sea by Boat: Mapping and Documenting Migratory Journeys and Experiences. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/pais/research/projects/crossingthemed/ctm_final_report_4may2017.pdf.

- Squire, V., N. Perkowski, D. Stevens, and N. Vaughan-Williams. 2021. Reclaiming Migration: Voices from Europe’s ‘Migrant Crisis’. Manchester: University of Manchester Press.

- Staeheli, L. A. 2010. “Political Geography: Where’s Citizenship?” Progress in Human Geography 35 (3): 393–400. doi:10.1177/0309132510370671.

- Stierl, M. 2019. Migrant Resistance in Contemporary Europe. London: Routledge.

- Sundberg, J. 2011. “Diabolic Caminos in the Desert and Cat Fights in the Rio: A Posthumanist Political Ecology of Boundary Enforcement in the United States-Mexico Borderlands.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101 (2): 318–336. doi:10.1080/00045608.2010.538323.

- Tan, K.-C. 2017. “Cosmopolitan Citizenship.” In The Oxford Handbook of Citizenship, edited by A. Schachar, R. Bauböck, I. Bloemraad, and M. Vink, 695–715. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tazzioli, M. 2023. Border Abolitionism: Migrants Containment and the Genealogies of Struggles and Rescue – Rethinking Borders. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Tazzioli, M., and N. De Genova. 2023. “Border Abolitionism: Analytics/Politics.” Social Text 41 (3 156): 1–34. doi:10.1215/01642472-10613639.

- Thompson, D. F. 1999. “Democratic Theory and Global Society.” Journal of Political Philosophy 7 (2): 111–125. doi:10.1111/1467-9760.00069.

- Topak, Ö. E. 2017. “Migrant Protest in Times of Crisis: Politics, Ethics and the Sacred from Below.” Citizenship Studies 21 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1080/13621025.2016.1191428.

- Tyler, I., and K. Marciniak. 2013. “Immigrant Protest: An Introduction.” Citizenship Studies 17 (2): 143–156. doi:10.1080/13621025.2013.780728.

- Vries, D., Guild, E. Leonie, and E. Guild. 2019. “Seeking Refuge in Europe: Spaces of Transit and the Violence of Migration Management.” Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 45 (12): 2156–2166. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1468308.

- Walters, W. 2008. “Acts of Demonstration: Mapping the Territory of (non-)Citizenship.” In Acts of Citizenship, edited by E. Isin and G. Nielsen, 182–207. London: Zed Books.

- Yemane, T., and H. T. Yohannes 2023. “Experts by Experience: What’s Beyond the Label?” Border Criminologies. 23 June 2023. https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/border-criminologies-blog/blog-post/2023/06/experts-experience-whats-beyond-label.

- Zanker, F., and J. Altrogge 2017. “The Politics of Migration Governance in the Gambia.” https://www.arnold-bergstraesser.de/sites/default/files/gambian_migration_politics_zankeraltrogge.pdf.