ABSTRACT

This systematic review explored the relationship between the social determinants of health and health seeking behaviour of individuals affected by armed conflicts. A systematic search of all available evidence was conducted through well-known academic databases. Seven studies met the inclusion criteria and were quality assessed. The synthesis revealed that the social determinants of health in times of conflict also determine the level of health seeking in these individuals. The social determinants were grouped in three main themes a) individual and economic b) sociocultural c) political and health systems. The three themes show that armed conflicts affect health seeking behaviour of individuals in a multi-layered manner with strong connections across the social determinants. This review shows that individuals are forced to choose between fulfilling their basic needs and attending health services. This is further compounded by the lack of health provision in conflict settings. Future research must address the social determinants of health when examining health seeking behaviour of conflict affected populations.

1. Introduction

Populations in conflict settings have the same fundamental rights to health as those living in stable environments (Austin et al. Citation2008). This is affirmed by global policies that have established the association between existing human rights and health rights (UN Citation1994, Citation2015). These rights are compromised in populations affected by conflicts despite global efforts to increase universal health coverage (Boerma et al. Citation2014; Reich et al. Citation2016; WHO Citation2014). Conflict affected populations are at risk of limited or no access to basic health services (Cope Citation2011; Herp et al. Citation2003; Krause, Meyers, and Friedlander Citation2006; Mullany et al. Citation2008; Pottie et al. Citation2015; Ruiz-Rodríguez et al. Citation2012). One reason for this may be that conflict alters health seeking behaviour in the affected individuals. The number of individuals at risk has been increasing along with an increase in armed conflicts which has been observed over the last decade (UCDP Citation2018). By 2016, some of the greatest humanitarian needs were found to be in ten countries with current or recent exposures to armed conflicts and with local conditions deteriorating year on year (Samarasekera and Horton Citation2017). Furthermore, epidemiological studies show that armed conflicts are ranked among the top-ten causes of death globally (Fürst et al. Citation2009; Lopez et al. Citation2006). These conflicts present challenges to the health systems, human health and overall health of civilizations due to population displacement and food scarcity (Hogan et al. Citation2010; Martins et al. Citation2006; Murray et al. Citation2002).

Previous research has highlighted the impact of conflicts on health. A 2010 review on maternal mortality from 1980–2008 in 181 countries recorded that half of all maternal deaths occurred in only six countries (DRC, Ethiopia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria and India), all with recent exposure to armed conflicts (Hogan et al. Citation2010). By the end of 2015, 99% of the global maternal deaths were documented in developing countries, with nearly 2 in 3 cases occurring in a crisis affected country (UNFPA Citation2015). Within Sub-Saharan Africa, countries emerging from or still in wars are among the hardest hit. For over a decade, the ten lowest ranked countries on Save the Children’s ‘State of the World’s Mothers Index’ were either post-conflict or conflict states and the ten lowest ranked countries on the UN Human Development Index were either emerging from or in conflict. Furthermore, 95% of all disaster fatalities are found in low- and middle-income countries (UNDP Citation2014). The health status of populations is more precarious in countries affected by conflicts than in non-affected countries (Hogan et al. Citation2010; Martins et al. Citation2006). Armed conflicts frequently result in an overwhelming loss of human life and infrastructure and displacement (Murray et al. Citation2002). There is evidence of an association between armed conflict and sexual vulnerabilities through sexual violence and intimate partner violence that mostly affect women (Clark et al. Citation2010). Sexual and gender-based violence is an element increasingly present in conflict and natural disaster settings (Petchesky Citation2008). The physical, psychological, social and cultural effects of rape and other forms of sexual violence often last for generations, resulting in enormous pain and suffering for affected individuals and their families (Chi et al. Citation2015a). Armed conflicts have been considered to have a significant impact on conditions in which people are born, grow, live and work and subsequently impact the health of affected populations (Marmot et al. Citation2008; Watts et al. Citation2007). These living conditions have also been known as the social determinants of health (WHO Citation2008) and the main drivers of health inequality (Bornemisza et al. Citation2010).

The aim of this review is to increase our understanding of the relationship between the social determinants of health and health seeking behaviour of individuals affected by armed conflicts. This review explores the factors that contribute to the health outcomes of conflict affected populations and studies the relationship between health and security, through the synthesis of all available qualitative studies. To our knowledge, this is the first review that explores the perceived social determinants in the context of armed conflicts.

2. Methods

2.1. Types of studies included

This literature review is PROSPERO registered (registration number: CRD42020163092). It adheres to recommendations in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Liberati et al. Citation2009). The PRISMA checklist for this systematic review is included in Supplemental Materials 1. The literature was reviewed from 1 January 2009 to 1 July 2019. Studies published within the last 10 years were included to capture the most recent and up to date evidence. The qualitative approaches considered in this review are ethnography, phenomenology and grounded theory (Bettany-Saltikov Citation2012). The aim of grounded theory is to develop a social phenomenon without preconceived theories of researchers by embracing different theories and perspectives. While phenomenology seeks to understand people’s behaviours and the factors that motivate them (Denzin and Lincoln Citation2018) by focusing on their understanding of their daily social and personal experiences (Munhall Citation2012), ethnography takes a cultural approach in research as it believes that culture influences people’s actions and thinking (Reeves et al. Citation2013).

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Before conducting the literature search, a set of selection criteria was created. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were formulated using the PEO/PEOT (Participant, Exposure, Outcome, Type of study) framework due to its suitability for selection of qualitative studies (Bettany-Saltikov Citation2012).

2.2.1. Inclusion criteria

2.2.1.1. Participants.

Research papers on populations affected by armed conflicts were considered for inclusion in this review. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) classifies armed conflicts as non-international conflicts between governmental and nongovernment forces or international conflicts, opposing two or more states (ICRC Citation2008).

2.2.1.2. Exposure

Studies on populations affected by armed conflicts or in post-conflict settings in low- and middle-income countries were included.

2.2.1.3. Outcomes

Studies included in the review were expected to present insights into the perceptions of and experiences with factors that determine and affect the health status as well as potential themes associated with the decision to seek health services of affected populations. Quantitative approaches can provide good information on observed patterns and trends, but they do not usually present a deeper understanding of what drives such patterns and trends (Patton Citation2015). We therefore focused on qualitative studies to investigate the depth of the relationship between health-seeking behaviour and armed conflict from the experiences, views and perspectives of affected individuals.

2.2.2. Exclusion criteria

Any study that did not meet the PEO/PEOT framework was excluded. The exclusion criteria used were:

A non-qualitative study design

Not English as the language of publication

Not affected by armed conflicts

Focus on a different topic than health

Conducted in a non-humanitarian setting or a non-post conflict setting

Conducted in high income countries

2.3. Search strategy

A search was conducted through the following databases: Proquest Health and Medical Complete, ScienceDirect, Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE) and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). The most suitable databases for this review were those focusing on health since they include medical and nursing related information that we were interested in.

During the initial search, relevant MeSH terms and keywords to each PEO/PEOT component were used and adapted to account for thesaurus differences (See Supplemental Materials 1). This review used the following search terms:

Participant: Internally displaced, displaced population*, displaced people, refugee*, conflict affected people, conflict affected population, crises affected population*

Exposure: armed conflict*, war*, post conflict*, man-made disaster*, disaster*, humanitarian cris*, emergency cris*, humanitarian setting*, crisis setting*

Outcome: social determinant*, social determinants of health, health, need*, poverty, education, living condition*, socioeconomic, access, barrier*

At the final stage, delimiters such as the language of publication (English), group year of publication and peer reviewed articles were used. Although some researchers (Jesson, Matheson, and Lacey Citation2011) have claimed that English language as a delimiter introduces language bias, it was applied due to costs of translation and time limitation. Peer reviewed articles were selected to ensure that studies of sufficient quality were included. An example of the search strategy is provided in Supplemental Materials 1.

Grey literature was also used although it was limited to providing policy and topical information. Furthermore, relevant reports and research journals from local and international research bodies such as Save the Children, the British Red Cross, the Health in Humanitarian Crises Centre and UNHCR were hand searched and the lists of references of retrieved relevant articles hand scanned. To ensure the validity and reliability of this review, published and unpublished results were compared to assess the similarities and differences.

2.4. Study selection process

To identify relevant articles, the retrieved studies were then screened through reading their titles and abstracts after duplicate removal. At this stage, if no clarity was provided from reading the articles’ title and abstract, a full text reading of relevant studies was undertaken and analysed against the pre-set eligibility criteria of the review by the two authors. Discrepancies were resolved with discussion between the two authors. The results were then transferred into the PRISMA flow diagram. An adapted paper selection form, piloted on several papers to test its feasibility (see Supplemental Materials 1), was used at both stages of the selection process.

2.5. Quality assessment

After the study selection process, a critical appraisal of included primary research papers was undertaken using the Critical Appraisal Skill Programme (CASP) tool to assess the quality of the included studies.

The CASP checklist includes ten questions addressing the relevance, validity and findings of individual studies. Through these questions, the technical rigour of included studies such as credibility and transferability was assessed (See Supplemental Materials 1). No study was excluded from this review based on the quality of their methodological approach. The reason behind this was that even low quality research papers might provide new insights despite having methodological flaws.

During the quality assessment process, each paper was assigned a number regarding the ten questions. For each question, every study scored 0 for a negative, 1 for uncertain and 2 for Yes. The maximum score for each study was 20. Studies with a score above 16 were considered as of good quality, those between 11–15 as moderate, while those below 10 were considered of poor quality.

2.6. Data extraction

A data extraction form adapted and guided by PEO components was created and used (see Supplemental Materials 1). The form guided the extraction of ten major pieces of information regarding the extraction date, the reviewer, bibliographical details of individual studies, their purpose, study area, study design, study setting, study population, exposure and outcomes.

2.7. Data synthesis

Qualitative meta-synthesis and an in-depth interpretation and analysis of collected information was applied by synthesizing data under main sub-themes and themes (Walsh and Downe Citation2005).

Thematic synthesis was chosen for this review. This approach involves three stages, which are mainly the identification of common themes from the primary studies, followed by organization into descriptive themes and generation of analytical themes. The initial two steps consisted of line-by-line coding of findings from included primary studies and involved developing descriptive themes from the initial codes. Studies were read individually more than once to make sure all the results reflecting the views, perceptions and perspectives of conflict-affected populations were collected. After examining several differences and similarities, a model structure of themes was created by grouping the concepts that had emerged. The process initially identified 80 codes, which were subsequently grouped into 20 descriptive themes. The final stage produced three analytical themes which are presented in detail next.

3. Results

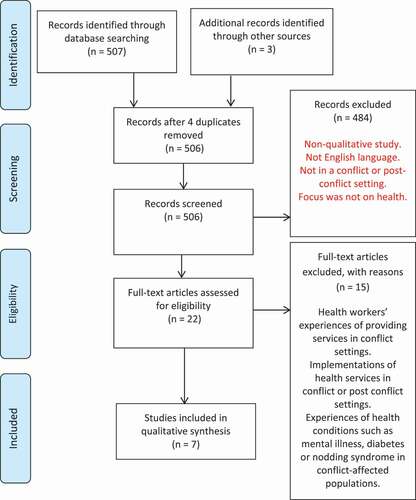

After completing the electronic search, 507 potentially relevant primary papers were found. Furthermore, hand searching the list of references in the retrieved studies revealed three additional studies to be reviewed. From these, four duplicates were identified and removed. This left a total of 506 studies which were screened to assess whether they were relevant to the research question. This resulted in 484 studies being excluded and the remaining 22 studies were then screened and assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Full text evaluation resulted in excluding 15 studies with 7 studies remaining for the thematic analysis. The main reasons for exclusion included health workers experiences of providing services in conflict settings, implementations of health services in conflict or post conflict settings, experiences of health conditions such as mental illness, diabetes or nodding syndrome in conflict-affected populations. See for the study selection process.

3.1. Characteristics of included studies

The review included seven studies which are shown in . One study (O’Laughlin et al. Citation2013) reported using a grounded theory approach while all the other six papers employed a qualitative exploratory approach. The rationale for the chosen methodology was reported in only four of the studies (Chi et al. Citation2015a; O’Laughlin et al. Citation2013; Roberts et al. Citation2009; Rujumba and Kwiringira Citation2010). The seven studies in this systematic review aimed to explore the determinants of health in populations affected by conflict. Two studies looked at the broad concepts of health while the majority of papers looked into maternal and reproductive healthcare. Rujumba and Kwiringira (Citation2010) explored the association between insecurity, culture and HIV/AIDS in Northern Uganda, while O’Laughlin et al. (Citation2013) focused on the experiences of HIV positive refugees in the access and use of HIV/AIDS testing services in Uganda. Roberts et al. (Citation2009) took a broad approach and explored the social determinants of health of internally displaced populations in northern Uganda, while Chi et al. published two studies specifically looking into the determinants of maternal and reproductive health service uptake in post-conflict Burundi and northern Uganda (Chi et al. Citation2015b) and the perceived effects of armed conflicts on such services (Chi et al. Citation2015a). Finally, Dumit and Honein‐Abouhaidar (Citation2019) explored the effect of the Syrian refugee crisis on healthcare providers in Lebanon.

Table 1. Summary of included studies

All seven studies were conducted in countries affected by armed conflict or in post-conflict settings. The majority of studies included were conducted in Sub-Saharan countries, mainly Northern Uganda (Roberts et al. Citation2009; Rujumba and Kwiringira Citation2010), Uganda (O’Laughlin et al. Citation2013) and Burundi and Northern Uganda (Chi et al. Citation2015a, Citation2015b). Two studies (Dumit and Honein‐Abouhaidar Citation2019; Kabakian-Khasholian et al. Citation2017) were conducted in the Middle East, specifically in Lebanon.

Participants were adults or in their teenage years and studies used a purposive sampling by specifically targeting particular locations such as health centres and specific towns to recruit the desired population sample. Variations were noted in the methods of data collection employed. Studies employed both focus group discussions (FGDs) and interviews as data collection methods or chose interviews alone as their data collection method. While O’Laughlin et al. took a grounded theory approach to data analysis (O’Laughlin et al. Citation2013), the remaining six studies used a thematic analysis (Chi et al. Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Dumit and Honein‐Abouhaidar Citation2019; Kabakian-Khasholian et al. Citation2017; Roberts et al. Citation2009; Rujumba and Kwiringira Citation2010). Details of the chosen methods of data analysis and how they were applied were presented in all seven papers. A summary of the main findings and themes can also be found in supplemental materials 2.

3.2. Quality assessment

While all studies used a purposive sampling to collect their data, only O’Laughlin et al. (Citation2013) reported the philosophical approach while the rest failed to mention it. Researchers should explicitly state their philosophical approaches and theoretical details to help the reader assess the congruity between theory and study methods, which ensures the research is rigorous (Babbie Citation2016; Miles, Huberman, and Saldana Citation2014). Some studies (Chi et al. Citation2015a, Citation2015b) employed prolonged engagement and the use of triangulation in data collection which are methods that increase the overall credibility of findings (Decrop Citation2004; Hadi and Closs Citation2016). The level of interactions and relationships between the researchers and their participants and their experiences or biases were not disclosed. Bracketing or providing a separate section on the role of the researchers could have revealed the researchers’ reflexivity, which enhances the validity of study findings (Jootun, McGhee, and Marland Citation2009; Tufford and Newman Citation2012). presents the included studies and their score on each of the ten questions from the CASP checklist.

Table 2. Quality assessment of included studies

3.3. Thematic analysis

80 initial codes were developed which were then grouped into 20 descriptive themes. From these descriptive themes, a total of 3 major analytical themes were developed from the synthesis, which is presented next in detail. See for the themes explored by each study.

Table 3. Analytical themes and included studies

3.3.1. Individual and economic determinants

The findings revealed that crises affected populations were likely to have poor health. The impact on health status works through several social determinants of health. At the individual level, the health effects of traumatic and violent events experienced during war and displacements were major determinants of the level of heath seeking behaviour and ultimately health outcomes. The specific traumatic experiences commonly referred to were rape, killings, atrocities, torture and abductions. This resulted in most participants experiencing ‘overthinking’, which further affected their mental health and eventually their physical strength and energy. For example, one participant explained ‘the anger of losing all the children is breaking my energy all the more. I no longer have any energy of going to work’ (Roberts et al. Citation2009, 5). Other typical examples are:

The conflict is also bringing mental illness as a result of bad acts. For example you can sit only to be told that a relative of yours has been killed. This could be your child whom you love most. Then you can think too much and this leads to mental illness. (Roberts et al. Citation2009, 4).

The economic determinants affect health through poverty as a result of war. Conflicts and displacements meant that affected populations no longer had access to their lands and/or sources of income. Further channels through which poverty was increased were lack of money or income due to lack of work opportunities, lack of food and shelter or housing and inability to adequately provide for their families. This further affected their physical health, especially in terms of ‘energy’ and ‘strength’ as well as emotional and mental health as some respondents noted:

My energy has gone down because there is nothing I can eat to give me energy to do work … We shall never have strength to do work and we shall remain weak. (Roberts et al. Citation2009, 5).

I feel sick all the time with pain. I cannot get food. That’s how it is in the camp. There is no means of getting money, food and nowhere to dig. The strength I had those days is no longer there. (Roberts et al. Citation2009, 4).

While the majority of participants were aware of the seriousness of some health conditions such as HIV/AIDS and the availability of health services, the findings of this review revealed that meeting basic and urgent needs constituted a greater priority than seeking medical care. Participants prioritized basic needs such as water, food and shelter over healthcare despite recognizing several health conditions as important problems (O’Laughlin et al. Citation2013). Indeed, these health conditions were perceived as a less imminent threat as they do not kill immediately compared to hunger. This was highlighted by responses like:

Yes we know AIDS exists, but we are much more worried about the conditions of our daily lives than HIV. We do not even find enough food to satisfy our stomachs, and what we worry about is what we will eat today. (Rujumba and Kwiringira Citation2010, 4)

… I think that it is because of the too much work that women have at home that stops them from going to the hospital. (Chi et al. Citation2015b, 7)

However, when conditions changed seeking medical care appeared to be a reasonable option. Circumstances that encouraged seeking medical care included the presence of incentives and mobile health services and inability to work due to disease severity (O’Laughlin et al. Citation2013).

Across all studies, it was evident that the complexities and vulnerabilities created by war such as insecurity and displacement worsened health outcomes. Study findings also revealed that women and girls were more frequently victims of sexual abuse due to war than men. The major themes that emerged included overcrowding that led to moral decadence, poverty, sex for money or other material things, rape and defilement. The ability to reach health facilities was impeded due to the state of the roads and long distances to health services. Indeed, most of people’s livelihood was destroyed during these conflicts along with destruction of infrastructure, in particular of health facilities, schools and roads. For example, the prevailing lack of security prevented people to travel and seek health services. Furthermore, the majority of participants revealed how overcrowded living conditions in congested camps as a result of displacement led to disease and poor health:

People should be taken back home so that there is fresh air because houses are spaced. People are too packed here. Somebody coughs from one corner, another from the other corner, and there is increased sickness. (Roberts et al. Citation2009, 5)

Displacement had not only pushed people into congested camps but had also resulted in social dislocation. Most participants especially parents reiterated that the congested camps had exposed children to sexual immorality at a younger age. The association between sexual immorality, social dislocation and insecurity was further emphasized by participants who noted that:

The war has pushed many people into camps; even children have been born and grown up without proper guidance. You can see the camp environment, which exposes children to immorality at an early age due to lack of privacy and some are lured into sex using small gifts. (Rujumba and Kwiringira Citation2010, 4)

I think if it were not of the conflict, we would not have been affected by HIV/AIDS [on this scale]. Before the conflict we had not seen these things and we did not even know about them. However, after the conflict we have seen bad things such as incurable diseases, rape or sexual violence by a man who is older than you and who is like your parents or your grandfather. These things did not exist before the war. We can say that Burundians have lost their cultural norms. (Chi et al. Citation2015a, 7)

… [T]he young children grew up in camps and were exposed to seeing bad and good things that have made them to get into sexual relationships very early and for that reason there are very many cases of child pregnancies. Apart from that there is prostitution; many of these young girls opt for sexual relationships just for money. (Chi et al. Citation2015a, 7)

It was therefore apparent that the unmet basic needs overshadowed the fear of suffering from a particular health disease. However, a closer look revealed that women’s concerns were more oriented towards basic needs while men’s concerns were about the larger community needs such as re-occurring insecurities, sanitation facilities and water. Furthermore, the increasing poverty and inability to meet survival needs led people to adopt risky sexual behaviours.

3.3.2. Sociocultural determinants

During analysis, it was evident that sociocultural and traditional rituals determined health seeking and affected the general health status of crisis-affected populations. For example, studies that explored infectious diseases found that sociocultural practices such as polygamy, the use of unsterilized instruments during traditional ceremonies and rituals, alcoholism, widow inheritance and early marriages were perceived to have fuelled the spread of HIV/AIDS in the communities. This was noted through responses like:

Men in this area have many wives and other women a side. A man generally with one woman is seen as if he is not a man enough. HIV is going to finish us (FGD Women Bolo). (Rujumba and Kwiringira Citation2010, 6)

Having many sexual partners, over use of alcohol and early marriages in our setting are major challenges in the fight against HIV and AIDS (District official). (Rujumba and Kwiringira Citation2010, 6)

Participants across all seven studies perceived that the total fertility rate increased during conflicts. When asked about the reason, both conflict-affected populations and healthcare providers explained the reason to be due to strong societal and cultural pressures to have more children to replace those lost in war as well as cultural desires for large family sizes.

It was an inter-ethnic conflict where one group stayed in while the other went out. … in both groups the goal was that of replacing the dead members … the idea was to have as many children as possible … (Chi et al. Citation2015a, 8)

We want to have more children because we lost many … . I lost my 8-year-old son. Everyone has lost one or two people from the family. If the situation allows, everyone will want to have more children (36–45 yr, outside ITS). (Kabakian-Khasholian et al. Citation2017, 80)

However, these needs and preferences were found to be in conflict with the difficult life in resettlement due to displacement:

One boy and one girl is more than enough in this situation, the less the better, I mean life is difficult, everything is expensive, you need to be able to provide for both children and save money (18–25 yr, outside ITS). (Kabakian-Khasholian et al. Citation2017, 80)

Some respondents revealed that they used traditional healers, medicines or rituals. The reliance on cultural habits and traditional remedies further delayed seeking medical care, resulting in worse health outcomes as stated by some:

I take the victim [of mental illness] to the hospital. If the hospital fails I will follow our culture and go to the witch doctor to find out the root cause of the problem. (Roberts et al. Citation2009, 6)

They [SRs] rely first on traditional remedies and once they exhaust them, they come to us. They end up with poorer health outcomes (ND.04). (Dumit Citation2019, 292)

For some religion seemed to be a key determinant in the use of health services, especially in coping with circumstances. For example, participants revealed that although they were aware of biophysical services and used them, they often returned to traditional healers. Typical comments were:

pray first … and then go to the witchdoctors to find out what has brought the madness. You can then finally try counsellors or health workers. (Roberts et al. Citation2009, 6)

you can go to a witch doctor. and also be saved in a born again church and God will help you if he so wish. You can also take the person to hospital and the treatment can reduce it. (Roberts et al. Citation2009, 6)

The extent to which it was believed to be effective and relied on was unclear. For example, a participant revealed that: ‘I have a lot of anger but the reason I give up taking my life is when I go to the church and the bible consoles me. Then I give up as everything is worldly. We don’t deal with hospital. We only depend on prayer’. (Roberts et al. Citation2009, 7) while another participant rejected religion stating that ‘I have given up religion. It does not help me. After all, my children are all dead’ (Roberts et al. Citation2009, 7). Furthermore, some traditional healers and herbalists were reported to lure their clients particularly women into sexual relationships which is a form of sexual exploitation with potentially negative consequences for these women (Roberts et al. Citation2009).

Overall response strategies were varied. Some relied on family and social networks for emotional support, while others felt that isolation was their preferred response to mental and emotional health challenges:

You go to friends and tell them and they advise you against thinking too much because it can result to sickness. I tell my husband that my brain is not working well or that I have pain which is giving me thoughts. (Roberts et al. Citation2009, 7)

when I have much thought, I isolate myself and sit in my house and sleep … I handle it alone. (Roberts et al. Citation2009, 7)

Furthermore, myths and beliefs about certain health services along with male partner opposition and conservative patriarchy appeared to further determine health seeking behaviour among participants:

Some say that family planning [modern contraceptive] is going to kill their eggs … While others think family planning can make one produce children without a head. Woman, IDI – Koro, Northern Uganda (Chi et al. Citation2015b, 7)

People think that when you are pregnant it is a normal condition and you do not have to go to the health facility. They feel that when you go there you are a coward. NGO-health provider, IDI – Gulu, Northern Uganda (Chi et al. Citation2015b, 8)

3.3.3. Political and healthcare system determinants

The political and healthcare system determinants revealed during synthesis were the effects of armed conflicts through poor quality of and limited access to health services. Some of the ways through which this happened included the targeted killings and abductions of health personnel, the destruction of health infrastructure along with the stealing of medical equipment and supplies and migration of healthcare providers as well as insecurities that prevented health seeking in search of appropriate health services. The destruction of health infrastructure and the attacks on health personnel led to a general breakdown of the system, which did not only disrupt or terminate the access to available services but also compromised its quality:

The conflict affected this. If we start with the quality, there was first of all the lack of personnel, there were no medical supplies, the distance between functional health facilities increased because there were health structures that were closed or destroyed, and there was also lack of medicines and materials. LHP-Policy maker, IDI – Ngozi (LHP 17) (Chi et al. Citation2015a, 5)

Many health personnel, including nurses and doctors were killed, while others fled to other countries. There were regions that were left without health personnel. LHP, FGD – Bujumbura (LHP 20) (Chi et al. Citation2015a, 5)

The targeted killings of health personnel were reported among populations in Burundi as opposed to those in Northern Uganda where they usually reported abduction of health providers:

Rebels wanted food, they needed sugar, they needed money, they needed medicine, drugs and they needed the health workers also; people to administer them the medicines. And they would get that from the hospital. So they would abduct the nurses. LHP, IDI – Gulu (LHP 5) (Chi et al. Citation2015a, 5)

Most participants felt that the most important political and health system determinant was the universal healthcare policies that facilitated free access to healthcare facilities by removing user fees. Participants appeared to give importance to the health system, especially the way they were treated by healthcare providers as noted by some participants:

Women are well treated and whenever you go [to the health facility] when you are pregnant, they receive you and they treat you well. Woman, IDI – Ruhororo, Burundi (Chi et al. Citation2015b, 8)

Many participants pointed out some healthcare providers’ attitudes as discouraging factors to seeking healthcare. Some of the attitudes noted were frequent absence or irregular presence of personnel at some facilities, abusive attitudes that were degrading to patients, extortion by health personnel despite on paper free healthcare and the inconsistent treatment of women when not accompanied by a male partner (some women were attended later or not attended to at all). Examples were:

Sometimes you can go [to the health facility] and you are told by the nurses to give them some money for the help they have given to you … Woman, IDI – Bobi, Northern Uganda (Chi et al. Citation2015b, 8)

During the war, even health personnel did not treat persons in the same manner. They were sympathetic to persons of the same ethnic group. It was dangerous. Even services were very expensive because medicines were regularly looted (from government health facilities) Woman, FGD – Kinama (W 16). (Chi et al. Citation2015a, 5)

Some factors were classified as positive determinants during the synthesis of the review. These included the use of mobile outreach clinics that increased the availability and accessibility of services in remote areas, the use of community health workers, reduction of travel distance as well as constructing more health facilities and recruiting more health personnel. Some participants admitted that the presence of material incentives such as delivery kits and bed nets encouraged them to seek medical care:

Some women go to the health facilities because another woman has gotten that incentive and you hear them saying that “if my friend has gotten this there, then I have to also give birth from the hospital in order to get mine”. Woman, FGD – Koro, Northern Uganda (Chi et al. Citation2015b, 8)

During the time of our testing, people used to get food and many people got tested because of the food. (O’Laughlin et al. Citation2013, 5)

4. Discussion

This review has focused on evidence of the relationship between social determinants of health and health seeking behaviour in populations affected by conflicts. Previous research looking into health outcomes of similar populations have highlighted the effect of sociocultural, economic and political factors and the serious impact of displacement and conflict on these determinants (Baingana, Bannon, and Thomas Citation2005; Miller and Rasco Citation2004; Silove Citation2005). Our findings suggest the major individual determinants of health seeking attitudes relate to trauma and violent experiences. Indeed, most of affected populations live in circumstances where the physical and mental health risks are caused not only by past experiences but also by fear of future violence. The findings of this review provide evidence on how affected populations describe the mental health effects of conflict, mainly ‘overthinking’ that can result in ‘madness’. There are similar findings in other studies on conflict affected populations where populations used the term ‘thinking too much’ to describe their poor mental health and its effects on physical health (Almedom Citation2004; Coker Citation2004; Sideris Citation2003).

The economic impoverishment as a result of war and displacement is a common determinant of health in most studies. Participants reported altering their health seeking behaviour due to poverty and due to a lack of work opportunities. These populations preferred to forgo their health needs as the opportunity cost of seeking health services was perceived to be too high. A qualitative study of refugee women in Rwanda reported that poor living conditions and overburden of daily work due to poverty negatively affected women who cared for their children and worsened health outcomes (Pavlish Citation2005). Furthermore, refugee women reported having little control over their circumstances and attributed the overburden of daily work to cultural and societal norms (Pavlish Citation2005). Other individual determinants noted by participants included overcrowding and being ‘cramped’ together which were believed to lead to physical illness and disease. These findings are reflected by Coker (Citation2004) who found a direct association between breathing and physical constriction. Coker (Citation2004) reports that freedom of cultural expression, freedom of movement and physical spaces that people can call their own are essential to life, to being human. The noted negative effects of overcrowding could also be linked to sharing intimate social spaces, and accommodating the plans of others, which particular groups of peoples have strict beliefs about.

Our findings have revealed overcrowding, security and poverty due to displacement as important determinants of health seeking behaviour. However, Mendelsohn et al. (Citation2014) concluded that the commonly believed determinants to treatment outcome such as political stability, security, work opportunities or poverty had either no relation to the outcome or were not unique to conflict affected populations. Another study exploring the health needs of displaced women reported that women felt a sense of loss of freedom to make decisions, which often led to feelings of insecurity and vulnerability (Pinehas, Van Wyk, and Leech Citation2016). Crea, Calvo, and Loughry (Citation2015) reported a higher likelihood of being physically healthy when affected populations felt safe and satisfied with their living conditions. It was therefore due to their poor living conditions that affected populations would sacrifice all health needs for their day-to-day survival needs. These behaviours could also be a reflection of the product of prolonged exposure to armed conflicts. Murray et al. (Citation2002) observe that the destructive impact of armed conflicts on basic facilities such as educational facilities (schools) often leads to poor educational and low literacy levels, which often result in increased levels of poverty and ignorance of the significance and value of health services. This is then reflected in the poor health seeking behaviour of conflict affected populations which was observed in this review.

The review synthesis emphasized the linkage between war, displacement and insecurity with the level of health seeking. Insecurity was perceived to have increased displacement of the population, put a strain on health services and increased poverty which led to risky behaviours, sexual immorality, prostitution, rape and defilement, further increasing the risk of diseases, especially infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS. This is not surprising as high prevalence of infectious diseases has often been associated with conflict zones (Fabiani et al. Citation2007). A review of the complex relationship between AIDS and conflict concluded that conducive conditions for factors that lead to increased risks of infection are created by armed conflicts, although this does not necessarily translate into high prevalence of the disease (Ciantia Citation2004). Becker, Theodosis, and Kulkarni (Citation2008) argue that conflict and the societal disarray that follows are special environments conducive to the epidemic spread of diseases. While some studies suggest that conflicts increase the risk of infectious diseases, the relationship between conflict and infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS remains contentious. A review of HIV/AIDS revealed low prevalence of HIV/AIDS in conflict affected people (Spiegel et al. Citation2007). Other studies have shown that the frequent engagement in high-risk behaviours of affected populations is a result of individual deprivation of their economic and social network, which increases their vulnerability to infectious diseases (Hankins et al. Citation2002; Khaw et al. Citation2000; Mills et al. Citation2006; Muhwezi et al. Citation2011; Spiegel Citation2004). Other studies have linked an increased likelihood of infectious diseases with sexual violence and intimate partner violence in conflict settings (Speizer Citation2010; Allen and Devitt Citation2012; Liebling-Kalifani et al. Citation2008). These findings point to the long-term impact of conflict on the breakdown of social and cultural norms and practices and to the fact that women are disproportionally affected since they are more likely to be victims or at risk of sexual violence. We believe the mechanism of impact on health seeking behaviour is through a reduction of trust in institutions and medical professionals especially if these are represented by men. Rujumba and Kwiringira (Citation2010) report that some traditional healers and herbalists have lured their female clients into sexual relationships although this is not explored further and the impact of this on these women’s health seeking behaviour is not discussed. It is likely that women with these kinds of traditional religious beliefs may have a different type of interaction with health services and this may impact on their health seeking behaviour. Therefore, a complex set of interventions addressing not only the root causes of such behaviours but also the predisposing factors are required to improve access to health services.

Our findings suggest that the mechanisms through which political determinants affected health seeking attitudes of affected populations varied from one setting to another. Although the main pathways reported in our results have been also observed elsewhere (Brentlinger et al. Citation2005; Ghimire and Pun Citation2006; Kinra et al. Citation2002). Other studies have reported serious damage to health infrastructure and affected populations resulting in death and migration of many health providers (Leather et al. Citation2006) and posing serious threats to access to basic health services (ICRC Citation2011, Citation2012). While this review identified reports of bias in the delivery of health services in conflict settings, a study in Colombia reported similar bias based on political and religious affiliations. Although the public health literature does not widely report on such practices, several studies conducted in post-conflict settings have reported discrimination in health delivery on ethnic lines (Bloom et al. Citation2006; Bloom and Sondorp Citation2006; Luta and Dræbel Citation2013; Sarkin Citation2000). Health providers should be impartial in providing healthcare and should encourage health seeking although armed conflicts might present challenges to establishing effective mechanisms to enforce this.

This review has shown that conflict affected populations face big challenges in relation to accessing healthcare services. This review provides insight by synthesizing seven qualitative studies reporting on the factors influencing the health seeking behaviour from the perspective of conflict affected individuals. This review adds to the current knowledge by providing the synthesis, the thematic analysis, direct quotes and the links between social determinants and health seeking behaviour in conflict and post-conflict settings. However, a limitation of this review is that it was limited to primary research studies indexed in MEDLINE, CINAHL and ProQuest. Furthermore, only studies published in English were included. Therefore, studies published in other databases or different languages might have been missed. Qualitative research does not aim to generalize findings but rather to apply insights, through synthesis of study participants’ experiences, to help us gain a deeper understanding of these events from the point of view of these individuals. We have adopted a qualitative approach so it is important to note that only some of the findings of this review could be transferrable across other conflict settings. Furthermore, focusing on qualitative studies meant that studies that took a quantitative approach to addressing social determinants of health in conflict areas were considered out of scope. Limitations to transferability are especially true since most of the included studies focused in a particular geographical area. For future research given the differences in religion, sociocultural attitudes and characteristics of each conflict setting, a detailed focus on ways healthcare services are provided or consumed is needed. Further studies should explore in depth the differences in the perceived social determinants of health between conflict affected populations in Sub-Saharan Africa and Lebanon. This is to ensure that the complex relationship between social determinants and health seeking behaviour of conflict affected individuals is effectively taken into account.

Supplementary Materials

Download PDF (538.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Elsa Munezero

Elsa Munezero is a medical doctor with experience working in both clinical and public health sectors with various NGOs in LMICs and the UK. She received a Msc in Public Health and a Master of Research from Glasgow Caledonian University. Her research interests are mainly in the area of general health including sexual and reproductive health, health seeking behaviours, health inequalities and social determinants of health, health policy and healthcare delivery, humanitarian crises and disaster response, and gender issues.

Sarkis Manoukian

Sarkis Manoukian is a Research Fellow in Health Economics working primarily in the area of Economic Evaluation of healthcare interventions. Sarkis has previously taught economics at the Department of Economics, University of Bristol and the Department of Economics, University of Essex. While at the University of Essex, he completed a PhD in Economics at the Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex. His research interests are mainly in the area of applied microeconometrics; including economic evaluation, decision analytic modelling, the economics of health seeking behaviour, the economics of healthcare associated infections, labour market behaviour, educational attainment and psychological well-being.

References

- Allen, M., and C. Devitt. 2012. “Intimate Partner Violence and Belief Systems in Liberia.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27 (17): 3514–3531. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260512445382.

- Almedom, A. M. 2004. “Factors that Mitigate War-induced Anxiety and Mental Distress.” Journal of Biosocial Science 36 (4): 445–461. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932004006637.

- Austin, J., S. Guy, L. Lee-Jones, T. McGinn, and J. Schlecht. 2008. “Reproductive Health: A Right for Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons.” Reproductive Health Matters 16 (31): 10–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31351-2.

- Babbie, E. 2016. The Practice of Social Research. 14th ed. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

- Baingana, F., I. Bannon, and R. Thomas. 2005. “Mental Health and Conflicts: Conceptual Framework and Approaches.” Accessed 15 December 2019. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/829381468320662693/pdf/316370HNP0BainganaMHConflictFinal.pdf

- Becker, J. U., C. Theodosis, and R. Kulkarni. 2008. “HIV/AIDS, Conflict and Security in Africa: Rethinking Relationships.” Journal of the International AIDS Society 11 (1): 3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2652-11-3.

- Bettany-Saltikov, J. 2012. How to Do a Systematic Literature Review in Nursing: A Step-by-step Guide. UK: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Bloom, J. D., and E. Sondorp. 2006. “Relations between Ethnic Croats and Ethnic Serbs at Vukovar General Hospital in Wartime and Peacetime.” Medicine, Conflict, and Survival 22 (2): 110–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13623690600621070.

- Bloom, J. D., I. Hoxha, D. Sambunjak, and E. Sondorp. 2006. “Ethnic Segregation in Kosovo’s Post-war Health Care System.” European Journal of Public Health 17 (5): 430–436. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckl270.

- Boerma, T., P. Eozenou, D. Evans, T. Evans, M. -P. Kieny, and A. Wagstaff. 2014. “Monitoring Progress Towards Universal Health Coverage at Country and Global Levels.” PLoS Medicine 11 (9): e1001731. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001731.

- Bornemisza, O., M. K. Ranson, T. M. Poletti, and E. Sondorp. 2010. “Promoting Health Equity in Conflict-affected Fragile States.” Social Science & Medicine 70 (1): 80–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.032.

- Brentlinger, P. E., H. J. Sánchez-Pérez, M. A. Cedeño, G. V. Morales, M. A. Hernán, M. A. Micek, and D. Ford. 2005. “Pregnancy Outcomes, Site of Delivery, and Community Schisms in Regions Affected by the Armed Conflict in Chiapas, Mexico.” Social Science & Medicine 61 (5): 1001–1014. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.022.

- Chi, P. C., P. Bulage, H. Urdal, and J. Sundby. 2015a. “Perceptions of the Effects of Armed Conflict on Maternal and Reproductive Health Services and Outcomes in Burundi and Northern Uganda: A Qualitative Study.” BMC International Health and Human Rights 15 (1): 7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-015-0045-z.

- Chi, P. C., P. Bulage, H. Urdal, and J. Sundby. 2015b. “A Qualitative Study Exploring the Determinants of Maternal Health Service Uptake in Post-conflict Burundi and Northern Uganda.” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 15 (1): 18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0449-8.

- Ciantia, F. 2004. “HIV Seroprevalence in Northern Uganda: The Complex Relationship between AIDS and Conflict.” Journal of Medicine and the Person 2 (4): 172–175.

- Clark, C. J., S. A. Everson-Rose, S. F. Suglia, R. Btoush, A. Alonso, and M. M. Haj-Yahia. 2010. “Association between Exposure to Political Violence and Intimate-partner Violence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory: A Cross-sectional Study”. The Lancet 375 (9711): 310–316. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61827-4.

- Coker, E. M. 2004. ““Traveling Pains”: Embodied Metaphors of Suffering among Southern Sudanese Refugees in Cairo.” Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 28 (1): 15–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MEDI.0000018096.95218.f4.

- Cope, J. R. 2011. Estimating the Factors Associated with Health Status and Access to Care among Iraqis Displaced in Jordan and Syria Using Population Assessment Data. PhD diss., Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University.

- Crea, T. M., R. Calvo, and M. Loughry. 2015. “Refugee Health and Wellbeing: Differences between Urban and Camp-based Environments in sub-Saharan Africa.” Journal of Refugee Studies 28 (3): 319–330. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fev003.

- Decrop, A. 2004. “Trustworthiness in Qualitative Tourism Research.” Qualitative Research in Tourism: Ontologies, Epistemologies and Methodologies 156: 169.

- Denzin, N. K., and Y. S. Lincoln. 2018. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Dumit, N. Y., and G. Honein‐Abouhaidar. 2019. “The Impact of the Syrian Refugee Crisis on Nurses and the Healthcare System in Lebanon: A Qualitative Exploratory Study.” Journal of Nursing Scholarship 51 (3): 289–298. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12479.

- Fabiani, M., B. Nattabi, C. Pierotti, F. Ciantia, A. A. Opio, J. Musinguzi, E. O. Ayella, and S. Declich. 2007. “HIV-1 Prevalence and Factors Associated with Infection in the Conflict-affected Region of North Uganda.” Conflict and Health 1 (1): 3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-1-3.

- Fürst, T., G. Raso, C. A. Acka, A. B. Tschannen, E. K. N’Goran, and J. Utzinger. 2009. “Dynamics of Socioeconomic Risk Factors for Neglected Tropical Diseases and Malaria in an Armed Conflict.” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 3 (9): e513. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000513.

- Ghimire, L. V., and M. Pun. 2006. “Health Effects of Maoist Insurgency in Nepal.” The Lancet 368 (9546): 1494. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69634-7.

- Hadi, M. A., and S. J. Closs. 2016. “Ensuring Rigour and Trustworthiness of Qualitative Research in Clinical Pharmacy.” International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 38 (3): 641–646.

- Hankins, C. A., S. R. Friedman, T. Zafar, and S. A. Strathdee. 2002. “Transmission and Prevention of HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections in War Settings: Implications for Current and Future Armed Conflicts.” Aids 16 (17): 2245–2252. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00002030-200211220-00003.

- Herp, M. V., V. Parqué, E. Rackley, and N. Ford. 2003. “Mortality, Violence and Lack of Access to Healthcare in the Democratic Republic of Congo.” Disasters 27 (2): 141–153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7717.00225.

- Hogan, M. C., K. J. Foreman, M. Naghavi, S. Y. Ahn, M. Wang, S. M. Makela, A. D. Lopez, R. Lozano, and C. J. Murray. 2010. “Maternal Mortality for 181 Countries, 1980–2008: A Systematic Analysis of Progress Towards Millennium Development Goal 5.” The Lancet 375 (9726): 1609–1623. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60518-1.

- ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross). 2008. “How is the term ‘Armed Conflict’ defined in International humanitarian law.” https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/resources/documents/article/other/armed-conflict-article-170308.htm

- ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross). 2011. “Health Care in Danger. Making the Case.” Accessed 15 December 2019. https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/publications/icrc-002-4072.pdf

- ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross). 2012. “Health Care in Danger: Violent Incidents Affecting Health Care (January to December 2012).” Accessed 15 December 2019. https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/reports/4050-002_violent-incidents-report_en_final.pdf

- Jesson, J., L. Matheson, and F. M. Lacey. 2011. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Jootun, D., G. McGhee, and G. R. Marland. 2009. “Reflexivity: Promoting Rigour in Qualitative Research.” Nursing Standard (Through 2013) 23 (23): 42.

- Kabakian-Khasholian, T., R. Mourtada, H. Bashour, F. E. Kak, and H. Zurayk. 2017. “Perspectives of Displaced Syrian Women and Service Providers on Fertility Behaviour and Available Services in West Bekaa, Lebanon.” Reproductive Health Matters 25 (sup1): 75–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2017.1378532.

- Khaw, A. J., P. Salama, B. Burkholder, and T. J. Dondero. 2000. “HIV Risk and Prevention in Emergency‐affected Populations: A Review.” Disasters 24 (3): 181–197. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7717.00141.

- Kinra, S., M. E. Black, S. Mandic, and N. Selimovic. 2002. “Impact of the Bosnian Conflict on the Health of Women and Children.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 80: 75–76.

- Krause, S. K., J. L. Meyers, and E. Friedlander. 2006. “Improving the Availability of Emergency Obstetric Care in Conflict-affected Settings.” Global Public Health 1 (3): 205–228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17441690600679939.

- Leather, A., E. A. Ismail, R. Ali, Y. A. Abdi, M. H. Abby, S. A. Gulaid, S. A. Walhad, et al. 2006. “Working Together to Rebuild Health Care in Post-conflict Somaliland.” The Lancet 368 (9541): 1119–1125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69047-8.

- Liberati, A., D. G. Altman, J. Tetzlaff, C. Mulrow, P. C. Gotzsche, J. P. Ioannidis, M. Clarke, et al. 2009. “The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses of Studies that Evaluate Healthcare Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration.” BMJ 339 (jul21 1): b2700. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700.

- Liebling-Kalifani, H., R. Ojiambo-Ochieng, A. Marshall, J. Were-Oguttu, S. Musisi, and E. Kinyanda. 2008. “Violence against Women in Northern Uganda: The Neglected Health Consequences of War.” Journal of International Women’s Studies 9 (3): 174–192.

- Lopez, A. D., C. D. Mathers, M. Ezzati, D. T. Jamison, and C. J. L. Murray. 2006. Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Luta, X., and T. Dræbel. 2013. “Kosovo-Serbs’ Experiences of Seeking Healthcare in a Post-conflict and Ethnically Segregated Health System.” International Journal of Public Health 58 (3): 377–383. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0403-8.

- Marmot, M., S. Friel, R. Bell, T. A. J. Houweling, and S. Taylor, and Commission on Social Determinants of H. 2008. “Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health.” The Lancet 372 (9650): 1661–1669. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6.

- Martins, N., P. M. Kelly, J. A. Grace, and A. B. Zwi. 2006. “Reconstructing Tuberculosis Services after Major Conflict: Experiences and Lessons Learned in East Timor.” PLoS Medicine 3 (10): e383. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030383.

- Mendelsohn, J. B., M. Schilperoord, P. Spiegel, S. Balasundaram, A. Radhakrishnan, C. K. C. Lee, N. Larke, et al. 2014. “Is Forced Migration a Barrier to Treatment Success? Similar HIV Treatment Outcomes among Refugees and a Surrounding Host Community in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.” AIDS and Behavior 18 (2): 323–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0494-0.

- Miles, M. B., A. M. Huberman, and J. Saldana. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

- Miller, K. E., and L. M. Rasco. 2004. The Mental Health of Refugees: Ecological Approaches to Healing and Adaptation. 1st ed. New York: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410610263.

- Mills, E. J., S. Singh, B. D. Nelson, and J. B. Nachega. 2006. “The Impact of Conflict on HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa.” International Journal of STD & AIDS 17 (11): 713–717. doi:https://doi.org/10.1258/095646206778691077.

- Muhwezi, W. W., E. Kinyanda, M. Mungherera, P. Onyango, E. Ngabirano, J. Muron, J. Kagugube, and R. Kajungu. 2011. “Vulnerability to High Risk Sexual Behaviour (HRSB) following Exposure to War Trauma as Seen in Post-conflict Communities in Eastern Uganda: A Qualitative Study.” Conflict and Health 5 (1): 22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-5-22.

- Mullany, L. C., C. I. Lee, L. Yone, P. Paw, E. K. S. Oo, C. Maung, T. J. Lee, and C. Beyrer. 2008. “Access to Essential Maternal Health Interventions and Human Rights Violations among Vulnerable Communities in Eastern Burma.” PLoS Medicine 5 (12): e242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050242.

- Munhall, P. 2012. Nursing Research. 5th ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Murray, C. J. L., G. King, A. D. Lopez, N. Tomijima, and E. G. Krug. 2002. “Armed Conflict as a Public Health Problem.” BMJ 324 (7333): 346–349. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7333.346.

- O’Laughlin, K. N., S. A. Rouhani, Z. M. Faustin, and N. C. Ware. 2013. “Testing Experiences of HIV Positive Refugees in Nakivale Refugee Settlement in Uganda: Informing Interventions to Encourage Priority Shifting.” Conflict and Health 7 (1): 2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-7-2.

- Patton, M. Q. 2015. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Pavlish, C. 2005. “Refugee Women’s Health: Collaborative Inquiry with Refugee Women in Rwanda.” Health Care for Women International 26 (10): 880–896. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330500301697.

- Petchesky, R. P. 2008. “Conflict and Crisis Settings: Promoting Sexual and Reproductive Rights.” Reproductive Health Matters 16 (31): 4–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31380-9.

- Pinehas, L. N., N. C. Van Wyk, and R. Leech. 2016. “Healthcare Needs of Displaced Women: Osire Refugee Camp, Namibia.” International Nursing Review 63 (1): 139–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12241.

- Pottie, K., J. P. Martin, S. Cornish, L. M. Biorklund, I. Gayton, F. Doerner, and F. Schneider. 2015. “Access to Healthcare for the Most Vulnerable Migrants: A Humanitarian Crisis.” Conflict and Health 9 (1): 16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-015-0043-8.

- Reeves, S., J. Peller, J. Goldman, and S. Kitto. 2013. “Ethnography in Qualitative Educational Research: AMEE Guide No 80.” Medical Teacher 35 (8): e1365–e1379. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.804977.

- Reich, M. R., J. Harris, N. Ikegami, A. Maeda, C. Cashin, E. C. Araujo, K. Takemi, and T. G. Evans. 2016. “Moving Towards Universal Health Coverage: Lessons from 11 Country Studies.” The Lancet 387 (10020): 811–816. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60002-2.

- Roberts, B., V. N. Odong, J. Browne, K. F. Ocaka, W. Geissler, and E. Sondorp. 2009. “An Exploration of Social Determinants of Health Amongst Internally Displaced Persons in Northern Uganda.” Conflict and Health 3 (1): 10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-3-10.

- Ruiz-Rodríguez, M., V. J. Wirtz, A. J. Idrovo, and M. L. Angulo. 2012. “Access to Medicines among Internally Displaced and Non-displaced People in Urban Areas in Colombia.” Cadernos De Saude Publica 28: 2245–2256. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2012001400004.

- Rujumba, J., and J. Kwiringira. 2010. “Interface of Culture, Insecurity and HIV and AIDS: Lessons from Displaced Communities in Pader District, Northern Uganda.” Conflict and Health 4 (1): 18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-4-18.

- Samarasekera, U., and R. Horton. 2017. “Improving Evidence for Health in Humanitarian Crises.” Lancet (London, England) 390 (10109): 2223–2224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31353-3.

- Sarkin, J. 2000. “A Review of Health and Human Rights after Five Years of Democracy in South Africa.” Medicine & Law 19: 287.

- Sideris, T. 2003. “War, Gender and Culture: Mozambican Women Refugees.” Social Science & Medicine 56 (4): 713–724. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00067-9.

- Silove, D. 2005. “From Trauma to Survival and Adaptation.” In Forced Migration and Mental Health, edited by David Ingleby, 29–51. Boston, MA: Springer.

- Speizer, I. S. 2010. “Intimate Partner Violence Attitudes and Experience among Women and Men in Uganda.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 25 (7): 1224–1241. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260509340550.

- Spiegel, P. B. 2004. “HIV/AIDS among Conflict‐affected and Displaced Populations: Dispelling Myths and Taking Action.” Disasters 28 (3): 322–339. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0361-3666.2004.00261.x.

- Spiegel, P. B., A. R. Bennedsen, J. Claass, L. Bruns, N. Patterson, D. Yiweza, and M. Schilperoord. 2007. “Prevalence of HIV Infection in Conflict-affected and Displaced People in Seven sub-Saharan African Countries: A Systematic Review.” The Lancet 369 (9580): 2187–2195. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61015-0.

- Tufford, L., and P. Newman. 2012. “Bracketing in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Social Work 11 (1): 80–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325010368316.

- UCDP. 2018. “Uppsala Conflict Data Program.” Accessed 15 December 2019. https://ucdp.uu.se/

- UN (United Nations). 1994. “United Nations (UN) Refugee Women and Reproductive Healthcare: Reassessing Priorities.” Accessed 15 December 2019. https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/resources/document/583-refugee-women-and-reproductive-health-care-reassessing-priorities

- UN (United Nations). 2015. “United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals”. Accessed 15 December 2019. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2014. “United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Fast Facts, Disaster Risk Reduction and Recovery.” Accessed 15 December 2019. http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/corporate/fast-facts/english/FF_DRR_11042014.pdf

- UNFPA. 2015. “United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Maternal Mortality in Humanitarian Crises and in Fragile Settings.” Accessed 15 December 2019. https://www.unfpa.org/resources/maternal-mortality-humanitarian-crises-and-fragile-settings

- Walsh, D., and S. Downe. 2005. “Meta‐synthesis Method for Qualitative Research: A Literature Review”. Journal of Advanced Nursing 50 (2): 204–211. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03380.x.

- Watts, S., S. Siddiqi, A. Shukrullah, K. Karim, and H. Serag. 2007. Social Determinants of Health in Countries in Conflict and Crises: The Eastern Mediterranean Perspective. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2008. “Social Determinants of Health.” Accessed 15 December 2019. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2014. “Making Fair Choices on the Path to Universal Health Coverage: Final Report of the WHO Consultative Group on Equity and Universal Health Coverage.” Accessed 15 December 2019. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/55888/