Historically, climate change and the resultant climate crisis have been looked at through a scientific lens in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, fossil fuels and renewable energy. While these issues are at the heart of the matter, the complex nature of this crisis means that its effects on economic development, human rights and systemic inequity cannot be ignored. Climate justice reframes the climate crisis in the context of human rights and focuses on the most vulnerable groups affected by climate change in order to ensure fair policies to address the impacts of global warming (Saraswat and Kumar Citation2016). These groups include lower income countries (LICs) as they have both fewer resources to adapt to climate change and high dependence on natural resources (OECD Citation2003).

Climate justice aims to ensure fair climate policies through different strategies ranging from financing lower and middle income countries (LMICs) to adopt sustainable development practices to decolonizing the climate change narrative by involving these countries in policies to limit global warming. Many of these strategies were discussed at the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow in tandem with previous commitments to climate justice made at the COP15 in Copenhagen 2009 to provide 100 billion dollars a year by 2020 (Ares and Loft Citation2021).

While examining and evaluating all the agreements made at COP26 is beyond the scope of this essay, in order to understand the resolutions made towards climate justice we need to understand the overarching goals of COP26. The main objective of COP26 was to devise a concrete plan for achieving the Paris Agreement of 2015 commitment to keep global warming to well below 2 degrees, with an aim of 1.5 degrees Celsius. For reference, to date, human activities have increased global temperatures by 1.1 degrees Celsius (Doyle Citation2021). This was done by countries submitting nationally determined contributions (NDCs) which highlighted their long-term greenhouse gas emissions goals in order to reach net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050 (United Nations Climate Change Citation2021).

In this essay, I will present the arguments for involving LICs in the climate change debate and assess whether they have been given adequate support to set up climate friendly initiatives in the context of the COP26 resolutions.

Scale of the problem

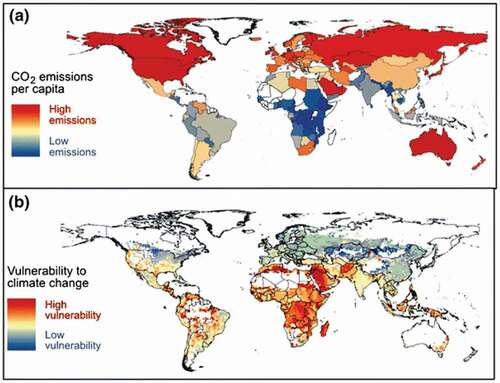

Figure 1. Source: (Saraswat and Kumar Citation2016).

represents the crux of the climate justice philosophy, which is that the countries who are the least responsible for climate change are the ones who are most vulnerable to the effects of it (Saraswat and Kumar Citation2016). Figure (a) above shows that higher income countries (HICs) are the greatest emitters of CO2 per capita while Figure (b) below demonstrates that the most at-risk countries are LICs such as those in Africa – almost a perfect inverse. Drought prone areas like the sub-Saharan African countries are becoming even more dry, as the number of undernourished people there has increased by 45.6% since 2012 (UN Food and Agriculture Organization Citation2019). This disparity is also seen by the rise in climate related migration, as climate change has been recognized as a major driver of human migration from sub-Saharan Africa to Europe (de Sherbinin Citation2020). In 2018, the World Bank estimated that three of the most vulnerable regions shown in the map, Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia, will give rise to more than 140 million climate migrants by 2050 (Rigaud et al. Citation2018).

An interesting point to note is the interplay between geographical location, poverty and climate change. For example, all the tropical countries, barring Singapore and Hong Kong, are not a part of the 30 countries classed as HICs by the World Bank (Balls Citation2001). Furthermore, all the high-income regions – North America, Western Europe, Northeast Asia, the Southern Cone of Latin America, and Oceania – are outside the tropics. This is attributed to factors such as the tropical climate being less conducive to farming by mechanisms of soil erosion, increased pests and parasites and reduced water availability – for example, in 1995, productivity per hectare of grain produced was higher by around 50% in temperate countries as compared to tropical ones (Balls Citation2001). However, these tropical countries are also the most at risk from climate change; in the top 10 nations identified as being most at risk from climate change by the risk analysis firm Maplecroft, all 10 of them were in the tropics (Martin Citation2015). This underscores the great divide and inequality caused by climate change, the poorest countries only stand to get poorer because of global warming. This inequality is what climate justice aims to address.

The ethical quandary of historic emissions

While we have covered how most LMICs are low carbon emitters, two of the world’s biggest polluters in terms of total CO2 produced are developing nations – China and India at first and third in the world respectively (Popovich and Plumer Citation2021). However, as underlined in the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention, member states have a ‘common but differentiated responsibility’ to reduce climate change and its effects. While China and India may be more responsible currently for climate change in terms of carbon dioxide production – it must still be noted that the historic production of CO2 by the HICs is greater than the amount produced by India and China – through 2017, the US and Europe combined have produced 47% of all emissions since the industrial revolution began while China has added 13% and India only 3% (Palmer Citation2021).

Therefore, the ethical argument made is why must LMICs eschew their cheap energy sources and sacrifice long term development goals that would enable them to reach the same economic development level as HICs and instead grow sustainably, while HICs used coal and fossil fuels unchecked during their industrial revolutions prior to the awareness of climate change. For this reason, I argue that financial reparations are the ethical and fair solution to this quandary. India has asked for these financial contributions to shift from coal to cleaner energy (Popovich and Plumer Citation2021). This is because as the HICs are asking fast developing nations to make short term financial sacrifices for the long-term health of our planet, these losses should be offset by financial contributions made by wealthier countries. In addition, the financial benefits enjoyed by HICs because of their historic fossil fuel use makes it only fair for them to contribute.

This ethical argument was showcased during COP26 when India and China, alongside the US and Australia, did not sign onto a vital agreement to phase out coal in richer countries by 2040 and poorer countries by 2050 (Palmer Citation2021). Over 40 countries agreed to the phasing out of ‘unabated coal and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies’ alongside some major banks like HSBC (Skidmore Citation2021). China has pledged to reach net-zero emissions by 2060 and India has committed to reach this goal by 2070 (Palmer Citation2021). To put this in perspective, the most common goal is 2050 so both China and India are 10 years and 20 years respectively later than their counterparts in reaching net-zero. This was argued by India based on historical greenhouse gas emissions being greater from more industrialized countries therefore these countries needed to take more responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, in terms of CO2 per capita India and China are lower than other HICs, 7.4 tons of CO2 per person was produced in China compared to 14.2 tons in the US and 15.4 tons in Australia (Popovich and Plumer Citation2021).

However, while the US coal production fell by 24.2% from 2019 to 2020 and has been on a downward trend since the late 2000s (U.S. Energy Information Administration Citation2018), China’s coal production continues to rise (Reuters Citation2021). This reflects the difference in development between the two countries, China still faces widespread energy poverty with 400 million people without access to clean cooking so is more likely to use cheap, efficient sources of energy like coal (Benoit and Tu Citation2020).

A global approach to tackle climate change

While the current Covid-19 pandemic may seem far removed from the climate crisis that faces us, there has been a key lesson from the pandemic that HICs should take when tackling climate change – the understanding that without a global response, the climate crisis cannot be resolved. This was shown in the Covid-19 pandemic where new variants such as the Omicron and Delta variants originated in countries with lower vaccination rates, South Africa and India respectively. When the Delta variant became predominant in India in April 2021, only around 1.4% of the population were fully vaccinated (Mathieu et al. Citation2021). This was demonstrated again in South Africa where Omicron was first identified in the Gauteng province, which has one of the three lowest vaccination rates in the country with only 32% vaccinated (Schraer and Horton Citation2021). This has been in large part due to vaccine inequality, as HICs are being vaccinated about 25 times faster than LICs (Randall Citation2021). However, as these LICs continue to have reduced vaccine coverage, the risk is that new variants will emerge which can reduce vaccine efficacy and prolong the pandemic (UNICEF Citation2021).

As seen in the Covid-19 pandemic, the climate crisis cannot be solved by HICs having a myopic focus on their own strategies and neglecting developing countries. This is due to two reasons; the issue of developing countries like China and India being major polluters, as illustrated previously, and the pollution haven hypothesis. The pollution haven hypothesis postulates that corporations will seek to avoid tighter environmental regulations by relocating to countries with more lax regulations regarding the environment (OECD Citation2017). These countries with more lax regulations tend to be LICs (Walter and Ugelow Citation1979). This is significant as corporations play a big role in climate change, with just 100 companies being responsible for 71% of global emissions (Griffin Citation2017). The pollution haven hypothesis, while presently not a key factor in relocation of corporations, has been supported by studies (OECD Citation2017) and highlights a need to implement strong environmental policies in developing countries. This can be done by actively involving LICs in international climate summits and ensuring their perspective is brought to the forefront, for example by representative assemblies such as the Association of Small Island States (AOSIS) which consists of 42 countries that are seen as highly vulnerable to sea level rise (Europen Parliament Citation2008). As these nations have common interests, their voices can be better heard as a coalition. Furthermore, ensuring LICs play an active role in determining policy leads to better policies and a stronger likelihood of implementation.

Resolutions at COP26

One of the main climate justice issues at COP26 was climate finance, whereby HICs fund LICs to support their efforts to address climate change and its impacts. Climate finance is provided by Annexe I countries, such as the US and UK, to non-Annexe I countries like Ethiopia, China and India. The background to this was a deal that was made at the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP15) in Copenhagen 2009 where Annexe I nations pledged 100 billion dollars a year by 2020 (Ares and Loft Citation2021). As of the COP26 in November 2021, there is a general consensus that this target had not yet been achieved and the new agreement formed at the COP26 agreed to meet this demand by 2023 (Ainsworth Citation2021).

On a deeper level, the systems of climate finance agreed upon seem to be fundamentally flawed in many ways. Firstly, the goal of 100 billion dollars needs to be looked at as a minimum as LICs need hundreds of billions of dollars to adapt to warming (Timperley Citation2021). In addition, there is a vast discrepancy in the figures that HICs state they have given, and the amount identified by multiple charities. For example, Oxfam, an international aid charity, estimated climate finance between 2017–2018 to be only $19 billion to $25 billion, one third of OECD figures (Timperley Citation2021). The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) mostly consists of HICs and bases its figures on those reported by donor countries. This discrepancy is because climate funding takes the form of grants and loans, and Oxfam says that only the value of loans at below market interest rates should be accounted for. Given the fact that LICs currently spend five times more on debt than climate change (Inman Citation2021), loans are not an ideal financial mechanism for support. Lastly, most climate finance is going into climate mitigation to reduce emissions, but not adaptation, building resilient infrastructure to cope with climate change (Timperley Citation2021). Adaptation is important because, as demonstrated in the Sub-Saharan Africa droughts, LICs already need to cope with a changing climate.

The proposed creation of a resilience and sustainability trust (RST) by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) could be the solution to these climate finance issues. The RST would be funded by re-channelled special drawing rights (SDRs) of the 650 billion dollars in SDRs recently approved by the IMF (OECD Development Matters Citation2021). The SDR is an asset that is held by a country that can be exchanged for money with other IMF members, and as its value is determined by the world’s five leading currencies – the US dollar, euro, Chinese yuan, Japanese yen and the UK pound- SDR value doesn’t tend to fluctuate. SDRs are allocated to all IMF member states in proportion to their quota, meaning they are heavily skewed to HICs which have 67.44% of the $650 billion and around 1.08% for the poorest, with the rest going to middle income countries (Munevar and Mariotti Citation2021). The recent SDR allocation was meant to help countries cope with the Covid-19 pandemic but most HICs will not need them (Eichengreen Citation2021). Channelling SDRs to the RST whereby LICs can obtain climate finance has several benefits. Firstly, these are not loans to be paid back so will not add to the already high debt faced by LICs. In addition, it improves transparency as the RST can follow where the money is going, as opposed to the current overestimation of climate finance made by organizations like the OECD. Lastly, it would allow LICs to determine their own finance spread, for example, how much money goes into adaptation or mitigation.

Conclusion

While climate justice did play a role in the discussions at COP26, clear objectives on how to achieve the equitable distribution of resources were not fully identified. Implementation of new strategies such as the RST, in addition to the 100 billion dollar a year pledge, is essential to ensure LICs that are the least responsible for climate change don’t face its catastrophic events. The climate crisis cannot be solved solely by action in the high-income nations, it requires a concerted global effort to keep the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees alive.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ainsworth, David. 2021. “What Needs to Change to Hit the $100B Climate Finance Target?” Devex, December 15. https://www.devex.com/news/what-needs-to-change-to-hit-the-100b-climate-finance-target-102063

- Alex de Sherbinin. 2020. “Climate Impacts as Drivers of Migration.” Migrationpolicy.org, October 20. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/climate-impacts-drivers-migration

- Ares, Elena, and Philip Loft. 2021. “COP26: Delivering on $100 Billion Climate Finance.” House of Commons Library, November 3. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/cop26-delivering-on-100-billion-climate-finance/

- Balls, Andrew. 2001. “Why Tropical Countries are Underdeveloped.” NBER, June. https://www.nber.org/digest/jun01/why-tropical-countries-are-underdeveloped

- Benoit, Philippe, and Kevin Tu. 2020. “Columbia | SIPA Center on Global Energy Policy | Is China Still a Developing Country? And Why It Matters for Energy and Climate. ’|’ Columbia | SIPA Center on Global Energy Policy | Is China Still a Developing Country? And Why It Matters for Energy and Climate.’| Is China Still a Developing Country? And Why It Matters for Energy and Climate.” Columbia.edu. https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/research/report/china-still-developing-country-and-why-it-matters-energy-and-climate

- Doyle, Alister. 2021. “Analysis: Dead or Alive? COP26 Climate Talks Strive to Save 1.5C Warming Goal.” Reuters, November 9. https://www.reuters.com/business/cop/dead-or-alive-cop26-climate-talks-strive-save-15c-warming-goal-2021-11-09/

- Eichengreen, Barry. 2021. “This SDR Allocation Must Be Different | by Barry Eichengreen - Project Syndicate.”|“this SDR Allocation Must Be Different | by Barry Eichengreen - Project Syndicate.” Project Syndicate, September 10. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/how-to-get-new-imf-sdrs-to-poor-countries-by-barry-eichengreen-2021-09

- Europen Parliament. 2008. “Engaging Developing Countries in Climate Change Negotiations Note IP/A/CLIM/NT/2007-17 PE 401.007.” https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/note/join/2008/401007/IPOL-CLIM_NT(2008)401007_EN.pdf

- Griffin, Paul. 2017. “The Carbon Majors Database CDP Carbon Majors Report 2017 100 Fossil Fuel Producers and Nearly 1 Trillion Tonnes of Greenhouse Gas Emissions.” https://cdn.cdp.net/cdp-production/cms/reports/documents/000/002/327/original/Carbon-Majors-Report-2017.pdf?1501833772

- Inman, Phillip. 2021. “Poorer Countries Spend Five Times More on Debt Than Climate Crisis – Report.” The Guardian, October 27. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/oct/27/poorer-countries-spend-five-times-more-on-debt-than-climate-crisis-report

- Martin, Richard. 2015. “Climate Change: Why the Tropical Poor Will Suffer Most.” MIT Technology Review, June 18. https://www.technologyreview.com/2015/06/17/167612/climate-change-why-the-tropical-poor-will-suffer-most/

- Mathieu, Edouard, Hannah Ritchie, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Max Roser, Joe Hasell, Cameron Appel, Charlie Giattino, and Lucas Rodés-Guirao. 2021. “A Global Database of COVID19 Vaccinations.” Nature Human Behaviour 5 (7): 947–953. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562021011228

- Munevar, Daniel, and Chiara Mariotti. 2021. “The 3 Trillion Dollar Question: What Difference Will the Imf’s New SDRs Allocation Make to the World’s Poorest?” Eurodad. https://www.eurodad.org/imf_s_new_sdrs_allocation

- OECD. 2003. “Poverty and Climate Change Reducing the Vulnerability of the Poor Through Adaptation Prepared By: African Development Bank Asian Development Bank Department for International Development, United Kingdom Directorate-General for Develop-Ment, European Commission Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, Germany Ministry of Foreign Affairs - Development Cooperation, the Netherlands Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development United Nations Development Programme United Nations Environment Programme the World Bank.” https://www.oecd.org/env/cc/2502872.pdf

- OECD. 2017. “Pollution Havens? Energy Prices are Not Key Drivers of Offshoring - OECD.” Oecd.org. https://www.oecd.org/economy/greeneco/pollution-haven-hypothesis.htm#: :text=The%20Pollution%20Haven%20Hypothesis%20argues,where%20environmental%20norms%20are%20laxer.&text=Higher%20energy%20prices%20are%20indeed,stock%20at%20the%20firm%2Dlevel

- OECD Development Matters. 2021. “Making Special Drawing Rights Work for Climate Action and Development.” Development Matters, October 7. https://oecd-development-matters.org/2021/10/07/making-special-drawing-rights-work-for-climate-action-and-development/

- Palmer, Ian. 2021. “Coal is Out at COP26 – Except for Countries Where It’s Still In!” Forbes, November 13. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ianpalmer/2021/11/13/coal-is-out-at-cop26–except-for-countries-where-its-still-in/?sh=5852a6a114f3

- Popovich, Nadja, and Brad Plumer. 2021. “Who Has the Most Historical Responsibility for Climate Change?” The New York Times, November 12. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/11/12/climate/cop26-emissions-compensation.html#: :text=China%2C%20home%20to%2018%20percent,fuels%20and%20industry%20since%201850

- Randall, Tom. 2021. “The World’s Wealthiest Countries are Getting Vaccinated 25 Times Faster.” Bloomberg.com, April 9. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-04-09/when-will-world-be-fully-vaccinated-pace-is-2-400-faster-in-wealthy-countries

- Reuters. 2021. “China’s Coal Consumption Seen Rising in 2021, Imports Steady.” U.S., March 3. https://www.reuters.com/article/china-coal-idUSL3N2L12A9

- Rigaud, Kanta Kumari, Alex de Sherbinin, Bryan Jones, Jonas Bergmann, Viviane Clement, Kayly Ober, Jacob Schewe, Susana Adamo, Brent McCusker, Silke Heuser, et al. 2018. Groundswell. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/29461.

- Saraswat, Chitresh, and Pankaj Kumar. 2016. “Climate Justice in Lieu of Climate Change: A Sustainable Approach to Respond to the Climate Change Injustice and an Awakening of the Environmental Movement.” Energy, Ecology and Environment 1 (2): 67–74. doi:10.1007/s40974-015-0001-8.

- Schraer, Rachel, and Jake Horton. 2021. “New Omicron Variant: Are Low Vaccination Rates in South Africa a Factor?” BBC News, December 3. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/59462647

- Skidmore, Zachary. 2021. “COP26: 40 Countries Agree to Phase Out Coal-Fired Power.” Power Technology, November 4. https://www.power-technology.com/news/industry-news/cop26-40-countries-agree-to-phase-out-coal-fired-power/

- Timperley, Jocelyn. 2021. “The Broken $100-Billion Promise of Climate Finance — And How to Fix It.” Nature 598 (7881): 400–402. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-02846-3.

- UN Food and Agriculture Organization. 2019. “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2019.” https://www.fao.org/3/ca5162en/ca5162en.pdf

- UNICEF. 2021. “COVID-19 Vaccines: 5 Reasons Why Dose Donations are Essential.” Unicef.org. https://www.unicef.org/coronavirus/covid-19-vaccines-why-dose-donations-are-essential

- United Nations Climate Change. 2021. “Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).” UNFCCC. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/nationally-determined-contributions-ndcs/nationally-determined-contributions-ndcs

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. 2018. “Coal - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).” Eia.gov. https://www.eia.gov/coal/

- Walter, Ingo, and Judith L. Ugelow. 1979. “Environmental Policies in Developing Countries.” Ambio 8 (2/3): 102–109. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4312437.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A54be08b81b54598d946d972fa532f4cf&ab_segments=&origin=.