Abstract

Purpose: The objective of this study was to investigate the effect of a local promotional campaign on preconceptional lifestyle changes and the use of preconception care (PCC).

Material and methods: This quasi-comparative study was carried out between February 2015 and February 2016 at a community midwifery practice in the Netherlands. The intervention consisted of a dual track approach (i) a promotional campaign for couples who wish to conceive and (ii) a PCC pathway for health care providers. Questionnaires were collected from a sample of women who received antenatal care during the pre-intervention (n = 283) and post-intervention (n = 257) period. Main outcome measures were preconceptional lifestyle changes and PCC use (defined as searching for information and/or consulting a health care provider).

Results: Women who were exposed to the intervention were significantly more likely to make at least one lifestyle change during the preconception period [adjusted OR 1.56 (95% CI 1.02–2.39)]. Women were especially more likely to preconceptionally reduce or quit [adjusted OR 1.72 (95% CI 1.05–2.83)] their alcohol consumption after exposure to the intervention. Although non-significant, it appeared that women who were exposed to the intervention more often prepared themselves for pregnancy by means of independently searching for preconception health information [adjusted OR 1.13 (95% CI 0.77–1.65)] or consulting a health care provider regarding their wish to conceive [adjusted OR 1.24 (95% CI 0.81–1.92)].

Conclusions: Exposure to a local promotional campaign targeted at preconceptional health was associated with improved preconceptional lifestyle behaviours, especially with regard to alcohol consumption, and has the potential to improve the use of PCC.

摘要

目的:探讨地方宣传活动对孕前生活方式的改变和孕前保健的影响。方法: 2015年2月至2016年2月在荷兰社区助产实践开展一项比较研究。干预措施采用双重办法:一是为有妊娠计划的夫妇开展宣传活动;二为健康夫妇提供孕前保健途径。分为两组, 干预前(283人)和干预后(257人), 收集这些女性的调查问卷。主要结果指标为孕前生活方式的改变和孕前保健 (定义为:收集信息和/或咨询卫生保健者)。结果:接受干预的妇女更有可能在孕前期间至少改变一种生活方式[调整OR值为1.56 (95%CI:1.02-2.39)]。妇女在接触干预后更有可能在孕前期间减少或停止饮酒[调整OR值为1.72 (95%CI 1.05-2.83)]。虽然这些没有显著性差异, 但是接受干预的妇女似乎更能够通过独立搜索孕前健康信息[调整OR值为1.13(95%CI为0.77-1.65)]或咨询保健者关于她们是否愿意怀孕[调整OR值为1.24(95%CI为0.81-1.92)]来为怀孕做好准备。结论:与孕前保健有关的地方宣传活动能够改善孕前生活方式, 尤其是酒精的消费, 并有可能提高孕前保健。

Introduction

Today, it is internationally recognised that the organisation of obstetric care should increasingly focus on prevention [Citation1–3]. Traditionally, women have been urged to seek prenatal care as soon as they have a positive pregnancy test. Yet, evidence shows that prenatal care is often initiated too late, as the critical period of organogenesis has by then already begun [Citation4]. Previous research has shown that almost all couples who are trying to conceive have at least one risk factor for which individual counselling by a health care provider is indicated [Citation5,Citation6]. Moreover, a prospective cohort study by Inskip et al. demonstrated that only a few women who are planning for pregnancy follow nutrition and lifestyle recommendations [Citation7]. The preconception period provides an opportunity to alter unhealthy behaviours in time, which could have a lasting positive effect on the (future) health outcomes of both mother and child [Citation8–10].

Preconception care (PCC) aims to improve pregnancy and health outcomes for mothers and their offspring by means of risk prevention, health promotion, and interventions prior to pregnancy [Citation11]. There are several ways of providing PCC, varying from individual PCC visits by couples who wish conceive, group information sessions and online education to folic acid fortification [Citation10,Citation12]. In general, key elements for PCC include optimising maternal health behaviours, screening for infectious diseases, obtaining genetic history, updating immunisation status and providing advice in case of chronic illnesses or medication use [Citation12].

Internationally, there is limited consensus on the implementation of PCC [Citation12]. Although the attention for PCC has grown substantially and many western countries have developed national guidelines, uptake rates of PCC among prospective parents remain low, varying between 27 and 39% [Citation13–15]. The delivery of PCC highly depends on the context. Differences in national health care and financing systems, local services, resources, facilities and organisational structures all affect possibilities for implementation [Citation16]. Therefore, regional and local approaches are currently recommended in which the delivery of PCC is tailored to its feasibility in a particular setting [Citation1,Citation2].

In previous studies by our group, the use of a local, tailored promotional campaign was advocated, which was suggested to have more potential to increase the uptake of PCC compared to mass promotional campaigns addressing the general public [Citation17,Citation18]. Yet, there is a general lack of evidence regarding the effectiveness of PCC interventions on maternal health behaviours and PCC use [Citation19,Citation20]. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the effect of a local intervention (i.e., promotional campaign) on preconceptional lifestyle changes and the use of PCC.

Material and methods

Study design

In this quasi-comparative study, a local intervention to promote preconception health and care was implemented in the municipality Zeist. Zeist is a medium-sized municipality located in the centre of the Netherlands, with ∼60,000 inhabitants of which 77% have a Dutch ethnicity whereas 13% have a non-western ethnicity [Citation21,Citation22]. Zeist has a birth rate of 10.5 per 1.000 inhabitants and one community midwifery practice [Citation21]. In the Netherlands, women whose pregnancies are considered low risk receive care at the primary care level by independently practicing midwives [Citation23]. In 2007, the Dutch Health Council recommended to integrate PCC in the health care system and, subsequently, guidelines for GPs and midwives as well as risk assessment instruments were developed [Citation24–26]. Yet, reimbursement of PCC in Dutch obstetric care has not been established up to now [Citation27].

The study took place at one community midwifery practice. The intervention, a local awareness campaign, was implemented from February 2015 to February 2016. Since the entire population of Zeist was exposed to the campaign, it was not possible to compare women who were exposed or non-exposed during the same time period. Therefore, in the pre-intervention period women were included to the no-exposure group, while in the post-intervention period women were included to the exposure group. For both populations, the same self-administered questionnaire was used.

Intervention

The intervention had a dual-track approach: (i) a promotional campaign to improve the awareness and reach of couples who wish to conceive and (ii) the implementation of a PCC pathway for PCC to improve referral and collaboration between health care providers. The design of the promotional campaign was based on the results obtained from a questionnaire and a focus group study in which experiences and needs of parents regarding PCC were assessed (unpublished data). The promotional campaign consisted of several items focused on preconception health and care. Health messages were framed in a ‘Did-you-know…?’ format, for example: ‘Did you know you should start using folic acid supplements four weeks before conception?’. Campaign items included posters, flyers, a local website, news-items and social media feeds. The posters and flyers were distributed among many local (public) places that were selected by participants from the focus group study, such as primary health care centres, dietician and physiotherapy practices, dentists, pharmacies, preventive child health services, community meeting places, childcare facilities, fitness clubs, supermarkets, shops and the library. During several weeks spread over the campaign period, large billboards were displayed alongside public roads. During the campaign period, individual PCC consults of ∼1 h were offered free of charge by the community midwifery practice in Zeist. Moreover, five plenary informational group sessions were scheduled.

The design of the PCC pathway was based on a qualitative study in which bottlenecks and solutions for the local delivery of PCC were assessed among local health care providers in Zeist [Citation17]. In 2014, a meeting was organised in which 30 local health care providers from different disciplines (midwives, obstetricians, fertility doctors, general practitioners, preventive child health care workers, maternity care nurses, physical therapists, pharmacists, and dieticians) were educated on the content and provision of PCC. The PCC pathway consists of four steps with guiding instructions, tips and tools: (i) how to identify the target population for PCC; (ii) how to refer couples for PCC consultation; (iii) how to address a potential wish to conceive with clients/patients and (iv) recommendations for couples who wish to conceive. In January 2015, the PCC pathway was distributed both digitally as well as in hard copy among 146 health care providers from the abovementioned disciplines in Zeist. More information on the intervention (in Dutch) is accessible at: www.zwangerwordeninzeist.nl.

Study sample

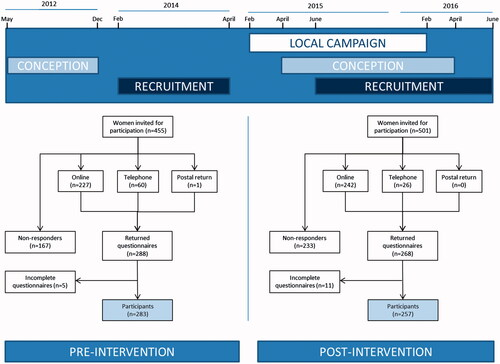

We invited 455 women who gave birth between January and September 2013 to participate in the pre-intervention study. For the post-intervention study, 501 pregnant women who conceived between April 2015 and April 2016 were requested to participate during their first prenatal visit (mostly between 7 and 10 weeks gestational age) (). For both groups, participation in the study required administering one questionnaire that took on average 12 min to complete. No extra effort from the participants in the post-intervention study was required, as the entire population was exposed to the intervention. All respondents were approached by the community midwifery practice by e-mail and were offered the possibility to either fill out the questionnaire online, to receive a hardcopy, or to make an appointment to fill out the questionnaire with a researcher by telephone. Reminders were sent by e-mail after two and four weeks after the original invitation. After six weeks, non-responders were approached by telephone. Sample size was based on the rule of thumb for logistic regression of at least 10 events per variable, expecting a 40% response rate, and additional requirement: sufficient recollection (i.e., childbirth not more than 1 year ago) and no overlap with inclusion for other scientific studies. This resulted in a 9-month time window in the pre-intervention study. In the post-intervention study, inclusion was continued until we achieved a similar sample size, limited by the time constraints of the study grant. It was not possible to measure exposed and non-exposed women during the same time period due to the nature of the intervention. Therefore, two groups of participants were recruited for the pre-intervention and post-intervention study (women who recently gave birth and pregnant women, respectively) to keep the limits of the total study duration.

Data collection and definitions

The questionnaires used in this research were designed specifically because no suitable validated questionnaires were identified. The questionnaires were identical, with the exception that the pre-intervention version held a section ‘needs for PCC’, while the post-intervention version held a section ‘awareness of the campaign’. The questionnaires were developed in collaboration with a team of experts and checked for content validity among eleven pregnant women who came in for a regular check-up at the community midwifery practice. All answers were retrospectively self-reported concerning participants’ current or most recent pregnancy. To study the effect of exposure to the intervention on PCC use, two outcome indicators were measured: (i) searching for preconception health information, and (ii) consulting a health care provider about the wish to conceive. To study the effect of exposure to the local intervention on lifestyle changes, four outcome measures were chosen which are amenable to change and have the potential to improve pregnancy outcomes: (i) healthier nutrition, (ii) folic acid supplement use, (iii) alcohol cessation, and (iv) smoking cessation. For each outcome measure, information was assessed regarding both the period prior to and after the positive pregnancy test, to be able to make a distinction between preconceptional and prenatal behavioural changes. Questions focused on the presence of risk factors (i.e., yes/no answers), but no information on frequencies or quantities was assessed to keep the length of the questionnaire acceptable. The questionnaire was available only in Dutch, since the vast majority of the population of Zeist masters the Dutch language. An explanation on confidentiality, anonymity and the purpose of the study was given prior to the questionnaire. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study and the study and questionnaire were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the UMC Utrecht (protocol no. 13-475).

Statistical analyses

Baseline data for the study population are presented as medians and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables or as numbers and percentages for categorical variables. To identify differences between the pre-intervention and post-intervention population, variables were either compared using Mann–Whitney U-tests or Chi-square tests for continuous and categorical data, respectively. Logistic regression analyses, with preconceptional lifestyle change and PCC use as dependent variables and pre-intervention and post-intervention as independent variable, were conducted to calculate crude odds ratios (OR) and accompanying 95% confidence intervals (CI). Adjusted OR were calculated taking into account the potential confounders age, educational level and nulliparity. All data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 22.0 [Citation28]. p-values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 540 women participated in this study, of whom 283 (52.4%) participated in the pre-intervention study and 257 (47.6%) participated in the post-intervention study (). Although the majority of women in both groups were Caucasian, slightly fewer women in the post-intervention group had a non-Caucasian ethnicity (82.9 versus 90.9%; p=.009). In addition, in the post-intervention group women were on average younger (33 versus 31 years; p=.001), less often nulliparous (45.8 versus 36.9%; p=.026) and less often smoked prior to conception (20.7 versus 13.0%; p=.026) (). All other socio-demographic characteristics were comparable between the two groups.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of women who participated in the study before (no exposure) or after (exposure) the local intervention to promote PCC.

More than half of the women who were exposed to the intervention (n = 142; 55.3%) could actively recall to have noticed at least one of the campaign items of which the billboard was most frequently recalled (n = 109; 42.4%). The yearly average of official PCC consultations at the community midwifery practice rose from one consultation prior to the intervention to 16 consultations during the intervention. The campaign website was visited by 4084 unique visitors during the intervention period.

demonstrates the differences between the pre-intervention and post-intervention group on preconceptional lifestyle changes and PCC use. During the intervention period, it appeared to be more likely that women searched for preconception health information (adjusted OR 1.13 (95% CI 0.77–1.65)) or consulted a health care provider regarding their wish to conceive compared to before the intervention [adjusted OR 1.24 (95% CI 0.81–1.92)], although this was not statistically significant.

Table 2. Preconceptional lifestyle changes and PCC use following exposure to a local intervention to promote PCC.

Eighty-eight women (62.4%) who were exposed to the intervention reduced or quit their alcohol consumption, which was significantly higher compared to women (n = 75; 48.7%) who were not exposed to the intervention [adjusted OR 1.72 (95% CI 1.05–2.83)]. In addition, it seemed more likely that women preconceptionally improved their nutritional habits [adjusted OR 1.30 (95% CI 0.88–1.93)], started folic acid supplement use [adjusted OR 1.41 (95% CI 0.95–2.10)] and reduced or quit smoking [adjusted OR 1.24 (95% 0.40–3.78)] after exposure to the intervention, but again this was not statistically significant. Overall, women who were exposed to the intervention were more likely to make at least one preconceptional lifestyle change compared to women who were not exposed to the intervention [adjusted OR 1.56 (95% CI 1.02–2.39)].

shows the differences between the non-exposed and exposed group on prenatal lifestyle changes. Exposure to the intervention led to a shift of more women starting folic acid supplement use during the preconceptional (67.2 versus 59.0%, respectively) instead of the prenatal phase (32.4 versus 38.7%, respectively). Moreover, more women quit drinking alcohol during the preconception period (26.0 versus 27.7%, respectively), but especially during the prenatal period (62.3 versus 70.9%, respectively) after exposure to the intervention.

Table 3. Preconceptional and prenatal lifestyle changes following exposure to a local intervention to promote PCC.

Discussion

Main findings

This study indicated that women who were exposed to a local PCC promotional campaign had healthier preconceptional behaviours compared to women who were not exposed. This could be attributed to their exposure to the PCC campaign. Women who were exposed better prepared themselves for their future pregnancy and, as such, more often improved their preconceptional lifestyle, especially with regard to alcohol cessation. The objective of our promotional campaign was not solely to increase the uptake of individual PCC consultations, yet to increase awareness, which could also bring women to act upon existing knowledge or to educate themselves on preconception health issues through evidence-based information. We found that women were far more inclined to acquire preconceptional health information themselves than to consult a health care provider. Yet, although the yearly number of PCC consultations rose from only one to sixteen following the intervention, exposure to the campaign seemed to improve preconceptional lifestyle.

Findings in relation to the literature

To the best of our knowledge, very few studies have been carried out on preconception health promotion beyond folic acid supplement use, neither has the effect of tailored PCC approaches in local primary care settings been studied. A recent systematic review showed that PCC interventions in primary care settings could improve maternal knowledge and self-efficacy [Citation20]. In two studies from the Netherlands and one study from the USA, preconceptional counselling has been associated with positive changes on maternal health behaviours [Citation29–31]. In accordance with our findings, two of these studies also found folic acid supplement use and alcohol use to be the two risk factors mostly influenced by PCC interventions. Elsinga et al. [Citation29] demonstrated that PCC initiated by general practitioners in the Netherlands increased women’s knowledge on pregnancy-related risk factors, improved preconceptional folic acid supplement use and reduced alcohol consumption during the first three months of pregnancy. Williams et al. [Citation30] used the United States population-based surveillance system (PRAMS) to measure PCC uptake, which was associated with daily prepregnancy multivitamin consumption and alcohol cessation prior to pregnancy.

Several studies have shown that large media campaigns are not always effective in promoting changes in preconceptional lifestyle [Citation31–34]. Increased awareness and behavioural change both require long-term efforts and are best served by a mix of interventions on the individual and community level delivered over a long period of time [Citation35]. Hammiche et al. [Citation31] studied the effect of tailored preconceptional dietary and lifestyle counselling and concluded that tailored counselling was more effective to increase folic acid supplement use with use rates up to 85% compared to 50% after a national media campaign [Citation34]. In addition to our findings that exposure to a local tailored intervention was beneficiary for the improvement of preconceptional lifestyles and the use of PCC, we also found that a local approach was appealing to women, since more than half of the participants could actively recall to have seen at least one promotional item. These results are promising, and contradicts previous research on the effect of marketing campaigns on reproductive health behaviours in which it was shown that messages are barely recalled and have limited behavioural effects [Citation36]. To date, there is insufficient evidence from trials on the effectiveness of PCC interventions [Citation19,Citation20]. To confirm our findings, this study should preferably be repeated in other local settings with clearly defined outcome measures to generate a larger and more heterogeneous data sample.

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of this study was the design of the intervention, which was based on a needs-assessment, conducted by a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods among couples who are trying to conceive and health care providers. Other strengths of this study include the high response rates to the questionnaires, which were developed in collaboration with a team of experts and validated among the target population. An important limitation of this study was the use of different non-exposed and exposed groups (women who recently gave birth versus pregnant women, respectively), because the time limit of the study did not allow for selecting respondents with similar recall periods. This may have inflicted differences due to recall bias, since pre-intervention participants administered the questionnaire between 13 and 24 months after conception while post-intervention participants administered the questionnaire between 2 and 8 months after conception. Participants in the pre-intervention and post-intervention group were not matched, as they originated from the same population and had similar socio-demographic characteristics [Citation37]. Nevertheless, we controlled for the influence of the possible confounding factors age, educational level and nulliparity. Another weakness of this study was the scope of the intervention, as it was set up to be a small-scale locally tailored promotional campaign that had to be performed with limited means. Therefore, our results are less generalisable to a wider population, although the intervention is designed to be easily adaptable to fit another municipality or region and the small-scale setting was necessary to assess the effect of a locally tailored intervention. Moreover, the use of self-reported, retrospective measures to assess women’s lifestyle behaviours while attempting pregnancy is suggested to negatively affect validity [Citation38]. The questionnaire included items on lifestyle behaviours, which are subject to a social desirability bias as respondents might feel the tendency to over-report positive healthy behaviour and under-report unhealthy behaviour. Yet, as this assumption holds true for both the non-exposed and exposed group, we expected no difference in reporting for both groups. Moreover, we did not ask about frequencies and quantities and solely assessed the presence and timing of behavioural changes (yes/no questions), which is supposed to limit over- and underreporting of behaviour [Citation38]. Subsequently, we could not examine potential dose-response relationships for micronutrient, alcohol and smoking status. Lastly, the campaign period may have been too short for a large and lasting effect on preconceptional lifestyle behaviour, as results from previous public campaigns in the Netherlands aimed at changing lifestyle (such as alcohol-free driving) indicate that it may take years to change public opinion and lifestyle behaviour [Citation39].

Implications for policy makers and clinicians

The ultimate future perspective is a perinatal health care chain in which PCC is fully integrated as the obvious first step to improve the future health of both mothers and children and, as such, becomes available for every couple with childbearing plans. To achieve this goal, health care providers and policy makers should switch their focus of pregnancy-related lifestyle interventions from reactive (prenatally) to active (preconceptionally). The presented PCC intervention serves the different needs of prospective parents by providing both separate preconception health information and PCC consultation. This supports the view that most couples who wish to conceive will benefit from evidence-based information to prepare themselves for pregnancy, while not every couple will attend a PCC consult. A starting point is to increase awareness on the importance of PCC among both prospective parents and health care providers by starting a social dialogue. A paradigm shift is needed for PCC to become just as self-evident as prenatal care, which will take many years and requires policy support both on the regional and national level.

Unanswered questions and future research

The findings of this study support emerging evidence indicating the preconception period as an important period to target pregnancy-related lifestyle interventions. To confirm our findings, this study should be repeated in other settings to generate a larger and more heterogeneous data sample. To date, there is insufficient evidence from controlled studies on the effectiveness of PCC interventions on the long-term health of mother and child [Citation19,Citation20,Citation40]. Moreover, literature on core preconception measures at the initiation of prenatal care—including pregnancy intention and access to care—is lacking [Citation3]. Therefore, future controlled studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of PCC interventions with clearly defined (clinical) measures during the preconception period with long-term follow-up.

Conclusions

This study shows that exposure to a local promotional campaign targeted at preconceptional health was associated with improved preconceptional lifestyle behaviours, especially with regard to alcohol consumption, and has the potential to improve the use of PCC. We recommend that PCC promotional activities should not solely focus on increasing the uptake of PCC consultations, since these may not necessarily be required for every couple with a wish to conceive to enhance their preconception health and wellbeing. Increased awareness can also motivate women to prepare themselves for pregnancy and attain positive preconceptional lifestyle changes. Although the current study is a locally embedded small observational study, its results are promising and need to be replicated in larger, longer-lasting studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Shannon GD, Alberg C, Nacul L, et al. Preconception healthcare delivery at a population level: construction of public health models of preconception care. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:1512–1531.

- Shawe J, Delbaere I, Ekstrand M, et al. Preconception care policy, guidelines, recommendations and services across six european countries: Belgium (flanders), Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2015;20:77–87.

- Frayne DJ, Verbiest S, Chelmow D, et al. Health care system measures to advance preconception wellness: consensus recommendations of the clinical workgroup of the national preconception health and health care initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:863–872.

- Johnson K, Posner SF, Biermann J, et al. Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care–United States. A report of the CDC/ATSDR preconception care work group and the select panel on preconception care. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–23.

- van der Pal-de Bruin KM, le Cessie S, Elsinga J, et al. Pre-conception counselling in primary care: prevalence of risk factors among couples contemplating pregnancy. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008;22:280–287.

- Jack BW, Culpepper L, Babcock J, et al. Addressing preconception risks identified at the time of a negative pregnancy test. A randomized trial. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:33–38.

- Inskip HM, Crozier SR, Godfrey KM, et al. Women’s compliance with nutrition and lifestyle recommendations before pregnancy: general population cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:b481.

- Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, et al. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:61–73.

- van der Zee B, de Beaufort I, Temel S, et al. Preconception care: an essential preventive strategy to improve children’s and women’s health. J Public Health Policy. 2011;32:367–379.

- Lu MC. Recommendations for preconception care. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:397–400.

- Atrash HK, Johnson K, Adams M, et al. Preconception care for improving perinatal outcomes: the time to act. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:3–11.

- de Weerd S, Steegers EA. The past and present practices and continuing controversies of preconception care. Community Genet. 2002;5:50–60.

- Frey KA, Files JA. Preconception healthcare: what women know and believe. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:73–77.

- Oza-Frank R, Gilson E, Keim SA, et al. Trends and factors associated with self-reported receipt of preconception care: PRAMS, 2004-2010. Birth. 2014;41:367–373.

- Stephenson J, Patel D, Barrett G, et al. How do women prepare for pregnancy? Preconception experiences of women attending antenatal services and views of health professionals. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103085.

- Boulet SL, Parker C, Atrash H. Preconception care in international settings. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:29–35.

- Poels M, Koster MPH, Franx A, et al. Healthcare providers’ views on the delivery of preconception care in a local community setting in the Netherlands. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:92.

- Poels M, Koster MPH, Franx A, et al. Parental perspectives on the awareness and delivery of preconception care. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:324.

- Whitworth M, Dowswell T. Routine pre-pregnancy health promotion for improving pregnancy outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD007536.

- Hussein N, Kai J, Qureshi N. The effects of preconception interventions on improving reproductive health and pregnancy outcomes in primary care: a systematic review. Eur J Gen Pract. 2016;22:42–52.

- Statistics Netherlands (CBS). Statline Database. The Hague: Statistics Netherlands (CBS). [cited 2017 Aug 30]. Available from: https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline#/CBS/en/

- Statistics Netherlands (CBS). Buurtmonitor Zeist, municipality Zeist. 2015. [cited 2015 Aug 24]. Available from: https://data.overheid.nl/data/dataset/buurtmonitor-gemeente-zeist

- Amelink-Verburg MP, Buitendijk SE. Pregnancy and labour in the dutch maternity care system: what is normal? The role division between midwives and obstetricians. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55:216–225.

- Health Council of the Netherlands. Preconception care: a good beginning. The Hague: Health Council of the Netherlands; 2007.

- de Jong-Potjer LBM, Bogchelman M, Jaspar AHJ, Van Asselt KM, Preconception care guideline by the Dutch Federation of GP’s. Dutch College of General Practitioners (NHG; 2011)

- Landkroon AP, de Weerd S, van Vliet-Lachotzki E, et al. Validation of an internet questionnaire for risk assessment in preconception care. Public Health Genomics. 2010;13:89–94.

- van Voorst S, Plasschaert S, de Jong-Potjer L, et al. Current practice of preconception care by primary caregivers in the Netherlands. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016; 21:251–258.

- IBM Corporation. SPSS statistics for windows. version 22.0 ed. New York: IBM Corporation; 2013.

- Elsinga J, de Jong-Potjer LC, van der Pal-de Bruin KM, et al. The effect of preconception counselling on lifestyle and other behaviour before and during pregnancy. Womens Health Issues. 2008;18(Suppl. 6):S117–S125.

- Williams L, Zapata LB, D’Angelo DV, et al. Associations between preconception counseling and maternal behaviors before and during pregnancy. Matern Child Health J. 2012; 16:1854–1861.

- Hammiche F, Laven JS, van Mil N, et al. Tailored preconceptional dietary and lifestyle counselling in a tertiary outpatient clinic in the Netherlands. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2432–2441.

- Temel S, Erdem O, Voorham TA, et al. Knowledge on preconceptional folic acid supplementation and intention to seek for preconception care among men and women in an urban city: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:340.

- van der Pal-de Bruin KM, de Walle HE, Jeeninga W, et al. The Dutch ‘folic acid Campaign’-have the goals been achieved? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2000;14:111–117.

- de Walle HE, de Jong-van den Berg LT. Ten years after the dutch public health campaign on folic acid: the continuing challenge. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64:539–543.

- Mullen PD, Evans D, Forster J, et al. Settings as an important dimension in health education/promotion policy, programs, and research. Health Educ Q. 1995;22:329–345.

- Hussaini KS, Hamm E, Means T. Using community-based participatory mixed methods research to understand preconception health in african american communities of arizona. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17:1862–1871.

- Faresjo T, Faresjo A. To match or not to match in epidemiological studies–same outcome but less power. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7:325–332.

- Gollenberg AL, Mumford SL, Cooney MA, Sundaram R, Louis GM. Validity of retrospectively reported behaviors during the periconception window. J Reprod Med. 2011;56:130–137.

- Ministry of General Affairs, the Netherlands. Dienst Publiek en Communicatie Nederland. Langetermijn effecten van publiekscampagnes op houding en gedrag. 2017. [cited 2017 Jun 02] Available from: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/publicaties/2013/06/27/langetermijn-effecten-van-publiekscampagnes-op-houding-en-gedrag

- Temel S, van Voorst SF, Jack BW, et al. Evidence-based preconceptional lifestyle interventions. Epidemiol Rev. 2014;36:19–30.