?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objectives: Determine the long-term risk of hysterectomy and ectopic pregnancy in women using the quinacrine hydrochloride pellet system of permanent contraception (QS) relative to the comparable risk in women using Copper T intrauterine device (IUD) or tubal ligation surgery (TL) for long-term or permanent contraception.

Methods: This was a retrospective cohort study, conducted in the Northern Vietnamese provinces of Ha Nam, Nam Dinh, Ninh Binh and Thai Binh. Women who had their first QS procedure, last IUD insertion or TL between 1989 and 1996 were interviewed regarding post-procedure health outcomes approximately 16 years post exposure.

Results: A 95% response rate resulted in 21,040 completed interviews. Overall incidence rates were low for both outcomes (91/100,000 women years of follow-up and 22/100,000 women years of follow-up for hysterectomy and ectopic pregnancy, respectively). After accounting for variations in baseline characteristics between women choosing QS vs. the other two contraceptive methods, no significant excess hazard of either hysterectomy or ectopic pregnancy was associated with QS.

Conclusions: No significant excess long-term risk of hysterectomy or ectopic pregnancy was found among a large group of women using QS vs. IUD or TL for contraception after an average 16 years of follow-up.

Chinese abstract

目的:判定采用盐酸喹吖啶微丸系统永久避孕(QS)的女性出现子宫切除术和异位妊娠的远期风险, 并与用含铜T型宫内节育器(IUD)或输卵管结扎手术(TL)用于长期或永久避孕的女性比较其相对风险。

方法:这是一个在越南北部省份(河南省、南定省、宁平省和太平省)进行的回顾性队列研究。我们随访了从1989年到1996年间第一次进行QS操作, 最后一次放置IUD或TL的女性在暴露后约16年的术后健康结局。

结果:本研究应答率为95%, 共21,040次完整的访视。两个结局总的发病率都很低(随访年份中发生子宫切除术的女性为91/100,000, 发生异位妊娠为22/100,000)。在考虑了选择QS和其他两种避孕方法的女性基线特征的变化后, 子宫切除术或异位妊娠与QS均无显著相关。

结论:在对采用QS或IUD或TL避孕的大样本妇女中, 未发现子宫切除术或异位妊娠更多的远期风险。

Introduction

The quinacrine hydrochloride pellet system of permanent contraception (QS) is a non-surgical procedure that can be performed outside of a hospital setting. The procedure follows a standardised protocol: transcervical application of seven 36 mg quinacrine pellets, administered in the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle, using a device similar to a Copper T intrauterine device (IUD) inserter. The currently recommended dosage regimen is two insertions applied one month apart. The quinacrine pellets dissolve and lead to sclerosis and subsequent occlusion of the fallopian tubes [Citation1]. A plausible mechanism for the cellular and molecular events involved in occlusion of the fallopian tubes by this contraceptive method was reported by Growe et al. in 2013. That work found the occlusion occurs as a pro-inflammatory response to the drug in the uterus and fallopian tubes. While the uterus returns to normal, mature collagen forms in the lumen of the fallopian tube, resulting in its permanent occlusion [Citation2].

Between 1989 and 1993 an estimated 50,000 Vietnamese women participated in a governmental clinical trial of QS. All procedures for the clinical trial were conducted at commune level clinics, which are the most local layer in Vietnam’s four-level public health service delivery hierarchy. The four levels of health care correspond to the four administrative levels of the government (i.e., national, provincial, district and commune levels). Residents are expected to seek primary healthcare from commune level health centres, which are their main contact with the public health system. Commune health centres also supervise village health workers who make house calls in local communal areas [Citation3].

Despite early indications of QS being an easy and safe method for long-term contraception, concerns arose regarding potential reproductive health risks. Those concerns were particularly focused on reproductive tract cancers, hysterectomy, ectopic pregnancy and death. A laboratory study suggesting the possibility of QS being carcinogenic [Citation4] was later shown to have a design inappropriate for testing the stated hypothesis and/or extrapolating its findings to humans [Citation5]. Previous analysis of data from the large, long-term follow-up study discussed in this manuscript found no significant excess risk of reproductive tract cancer among women treated with QS vs. comparators using IUD or tubal ligation surgery (TL) for contraception [Citation6]. Previous studies among various subsets of the Vietnam clinical trial participants compared risk of hysterectomy and ectopic pregnancy between women using QS vs. other contraceptive methods. No excess hysterectomy risks were identified and observed differences in ectopic pregnancies were generally accounted for by factors other than contraceptive method (e.g., small sample sizes, small numbers of events or high failure rates prior to refinement of the QS procedure) [Citation7–11].

In order to address the reproductive health concerns in a more definitive manner than previous attempts, a carefully controlled retrospective cohort study was conducted between 2007 and 2008 among a large group of the clinical trial participants to determine long-term health status following the QS procedures. Women in four provinces, along with age-clinic-date-matched controls who used IUDs or TL for contraception, were interviewed an average 16 years following their contraceptive procedures. Low migration rates among rural Vietnamese [Citation12] combined with the country’s health care system centred around local area clinics, facilitated identification of women for interview in this long-term follow up study.

Results from that study regarding comparative long-term incidence and risk between the QS and control cohorts of hysterectomy and ectopic pregnancy are reported herein.

Methods

Cohort identification

The maximum number of interviews, within the constraints of available funding, was conducted with women in the northern Vietnamese provinces of Ha Nam, Nam Dinh, Ninh Binh and Thai Binh. All participants had their first QS procedure, last IUD insertion or TL between 1989 and 1996.Footnote1 QS-exposed subjects were identified from procedure logbooks at commune level health clinics in each province. The study’s sponsoring organization (ISAFFootnote2) identified clinics known to have regularly provided permanent contraception services as potential study sites. All 784 health communes in the four provinces were included in the survey, although some had few women treated with QS. Dr. Do Trong Hieu served as the Vietnam in-country study coordinator, and worked with The Institute for Development and Community Health (LIGHT) to conduct the study. Lists of comparator subjects who had IUD insertions or TL were compiled from clinic logbooks and district health centre records in three provinces. In the fourth province (Nam Dinh), IUD and TL patient records had been destroyed in a flood. TL comparators in that province were identified from district health centre records, and IUD comparators were located via community survey. From women identified by community survey in Nam Dinh as having used IUDs for contraception, two potential comparators per QS subject were randomly selected from all potential matches. The assigned interviewer chose which of the two women to contact for the study. In all provinces, the goal was to match comparators to QS women by the clinic at which the procedure was done, quarter of the calendar year in which their procedure was completed, and age at the time of their qualifying contraceptive procedure (±2 years). Matching by age at procedure took precedence over matching by quarter year of the procedure. As the primary impetus for the study was an examination of long-term risk of reproductive tract cancers, women with cancers prior to their procedure were excluded from the study. At least one comparator match was identified for each QS woman. In cases where multiple matching comparators were found, one comparator was randomly selected from the group.

Data collection

English language case report forms (CRFs) were developed by The Degge Group (see Supplemental Information A). Questions were modelled on questionnaires from previously published studies collecting similar types of data, with redundant questions included for verification purposes [Citation13–27]. The CRFs were independently reviewed by a panel of three cancer epidemiologists. CRFs were translated into Vietnamese by an employee of the Vietnam Ministry of Health, and the LIGHT staff revised the documents as needed to accommodate practical aspects of the data collection process. Data collection procedures were approved by a Vietnamese institutional review board prior to implementation.

Local clinic staff first abstracted demographic data and information about each subject’s first QS procedure, last IUD insertion or TL from health centre records for most women. For IUD comparators in Nam Dinh, the data were collected as part of the community survey. Each woman’s qualifying procedure was identified as her Index Procedure (IP).

Interviews were then attempted for all women identified as having undergone the QS procedure, for all matched comparators in the provinces of Ha Nam, Ninh Binh and Thai Binh, and for the selected comparators in Nam Dinh. All interviews were conducted by physiciansFootnote3 who were carefully trained by LIGHT in proper administration of the health status questionnaires.

After obtaining informed consent survey participants (or proxies) were asked about their post-IP history of obstetric and gynaecologic events (including IP/post-IP details), histories of chronic diseases, hospitalisations and surgeries, family history of cancer and environmental exposures. The majority of interviews (98%) were held in person, although in a few cases (e.g., when a woman had moved away from the clinic area) contact was via telephone. Interviewers probed for details about reported outcomes, in particular any surgeries or hospitalisations.

Staff familiarity with women seen at area clinics facilitated review and correction of responses at the local level, as needed. Completed CRFs were reviewed by LIGHT staff including four physicians, one from each of the four provinces involved in the survey, and doubts about any responses were discussed by that team. Reviewers’ questions were returned to the local clinics for verification.

Data entry

Degge developed an MS-Access database for computerised entry and storage of the study data. Laptop computers on which the database programme was installed were provided to the Vietnam research staff at LIGHT. Information collected on the CRFs was translated from Vietnamese to English as it was transcribed by the project officers into the computerised database. Translation of unfamiliar terms was verbally provided to the project officers by Dr. Nguyen Bich Ngoc in consultation with Dr. Do Trong Hieu. Data files were transferred to ISAF and then to the Degge investigators for cleaning and analysis.

Steps were implemented to maximise the accuracy and completeness of the data entry. While the interviews were underway, a 5% random sample of questionnaires and their corresponding MS-Access records were provided to the Degge staff for review. The small number of data entry errors and translation issues identified in the sample were corrected and feedback provided to interviewers and data entry operators through LIGHT.

Data verification

Upon receipt of digitised survey data, Degge Group staff compiled lists of all outcomes identified from the interview database, and returned those lists to LIGHT for review, confirmation and/or correction by the local health clinics. Three Vietnamese cancer pathologists independently adjudicated reported outcomes through examination of hospital records, although missing records allowed only a small number of events to be verified in this way.

Following completion of all data collection and verification, a separate academic epidemiologist conducted a detailed examination of the data to identify any patterns of missing and/or biased dataFootnote4. The data were examined according to various patient demographic and health characteristics, and also by procedure cohorts, provinces and interviewers. Equitable completeness of survey responses across the examined groupings confirmed the quality of interviewer training and data entry.

Statistical Analysis

Separate analyses were conducted for hysterectomy and ectopic pregnancy outcomes. Follow-up time was measured from the IP date to the earliest of the outcome of interest (i.e., hysterectomy or ectopic pregnancy), death or interview date.

Hysterectomy and ectopic pregnancy incidence rates for the contraceptive cohorts were calculated as:

Cox proportional hazards regression (CPH) analyses were conducted to compare risks of hysterectomy and ectopic pregnancy over time between the QS and IUD/TL cohorts. A propensity score (PS) [Citation28,Citation29], designed to account for differences in potentially confounding baseline characteristics of women enrolled in the QS vs. IUD/TL cohorts, was included as a covariate in adjusted versions of the CPH models. (See for the list of variables included in the preliminary and reduced PS models).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics included in logistic regression model for calculation of propensity score.

Results

Respondents

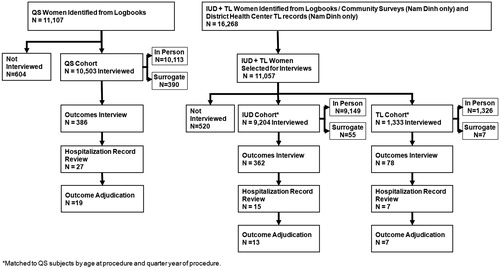

A total of 11,107 women who had undergone the QS procedure, and 16,268 women who had IUD insertions or TL were identified. Between December 2007 and January 2009, a total of 21,040 interviews were completed, for an overall response rate of 95%. Interviews were conducted for 10,503 QS subjects (94.6% response rate) and a combined 10,537 IUD/TL subjects (95.3% response rate) (). Most of the identified women were available for in-person interviews (N = 20,588; 93% of all women with whom interviews were attempted). A small proportion of interviews (2% overall) were conducted with family or well acquainted clinic staff members. Those surrogate interviewees were typically enlisted when a subject was unavailable due to death or relocation.

Data from 21,037 of the 21,040 interviews conducted were analysed. One IUD case was omitted from the analysis because the respondent reported a cancer event that occurred earlier than their IUD insertion. Two TL cases reported hysterectomy dates that preceded their TL surgeries. Those interviews were also dropped, as the date ambiguity could not be clarified.

Similarities between women in the QS vs. comparator cohorts with regard to age and follow-up time reflect the efficiency of the system used to match subjects ().

Table 2. Subject characteristics.

While QS subjects were slightly older than IUD comparators at the time of their procedure, the average difference was less than two months. QS women were younger than the TL comparators by less than four months, on average (p < .01). At the time of the survey, the QS group was slightly older (by less than three months, on average) than both comparator groups (p < .01 and p < .05 for comparisons to the IUD and TL cohorts, respectively). The average length of total follow-up ranged from 16.04 years in the TL cohort (median 16.08 years), to 16.33 years in the QS cohort (median 16.38 years) and 16.62 years in the IUD cohort (median 16.42 years). Roughly half the subjects in the QS and IUD groups lived in Nam Dinh, while a similar proportion of the TL women were in Ha Nam. At least 95% of women in each procedure group were married. The QS and TL groups had similar levels of completed education (6.7 and 6.6 years on average, respectively), while IUD cohort members’ education slightly exceeded that of the QS cohort with an average of 6.8 years (p < .01).

Women in the QS cohort reported more lifetime pregnancies, on average, than women in the IUD and TL cohorts (4.5 vs. 3.8 and 4.0, respectively, p < .01 for each comparison). The proportions of the QS cohort reporting ectopic pregnancies (0.5%), abortions (36.7%), and stillbirths (1%) in their lifetimes (i.e., either before or after the procedure that qualified them for their study cohort membership) exceeded the corresponding proportions in the IUD cohort (0.2, 25.6 and 0.6%, respectively, p < .01 for each comparison). The proportion of QS women reporting at least one miscarriage in their lifetime was significantly higher than in the IUD or TL cohorts (12.1% vs. 10% and 9.6%, respectively, p < .01 for both comparisons).

Two-thirds of women in the QS cohort (66%) reported use of other contraceptive methods in their lifetime, compared to 58% of the TL cohort (p < .01) and 20% of the IUD cohort (p < .01) (). In the specific context of contraceptive use, 499 (2.4%) of all women reported ever using birth control pills. Those 499 women reported an average of 2.4 years’ total use. Combined with additional information from a general health question asking whether women had ever used any hormones in their lifetime, birth control pills or other reproductive hormones that might have been prescribed to treat gynaecological maladies were mentioned by 554 women (2.6%). While still quite low in absolute terms, proportionally fewer women in the QS group reported the use of these hormones compared to the IUD cohort (1.3% vs. 4.4%, p < .01). A similarly low proportion of the TL cohort reported use of birth control pills or other reproductive hormones (1.4%).

Table 3. Reproductive history.

Hysterectomy results

Hysterectomy incidence

A total of 314 hysterectomies were reported during the post-IP time period, representing 1.5% of all study participants. shows the distribution of the 314 hysterectomies among women in the QS, IUD and TL cohorts. For the entire study group, hysterectomies occurred at a rate of 91 per 100,000 women years of follow-up time. The rate in the QS group was higher than that of the IUD comparator group and lower than the TL rate (97.6 vs. 75.2 and 151.3, respectively, per 100,000 women years of follow-up time; p < .05 for both comparisons). The median interval between IP and hysterectomy was 12 years overall, and was not markedly different between cohorts.

Table 4. Hysterectomies reported, incidence rates and hazard ratios.

Retrospective calculations indicate that the reported number of hysterectomies provide 80% power to detect a hazard ratio of 1.4 in this study population.

Hysterectomy survival analysis

The unadjusted CPH analyses found a significant excess risk of hysterectomy associated with QS, compared to IUD users, during the follow-up period (HR = 1.4; 95% CI = 1.1–1.7, p = .01) although there was no significant difference in risk after adjusting for baseline differences by inclusion of the PS (). Compared to the TL group, on the other hand, the QS cohort had a significantly lower risk of hysterectomy through the follow-up period for both the unadjusted (HR = 0.6; 95% CI = 0.4–0.9, p = .02) and PS adjusted models (HR = 0.6; 95% CI = 0.4–0.8, p < .01).

Reasons for hysterectomy

Interviewers probed to determine the underlying reasons for hysterectomies among women reporting this outcome. Uterine fibroids were cited as the reason for their hysterectomy by the vast majority of the 314 women who had this surgery (90%) (). Ovarian cysts were reported by a total of 13 women (4%) and several other reasons were each reported by no more than four women.

Table 5. Reasons reported for hysterectomy by procedure.

Characteristics of women with and without hysterectomies

compares gynaecologic histories of women in this study who did/did not report hysterectomies during the post-procedure time period. Women in the two groups were similar with regard to age at procedure, age at birth of first child and numbers of live births. However, the distribution of lifetime pregnancies varied between the two groups (p < .01). Among women with hysterectomies the proportion reporting five or more pregnancies was 12 percentage points higher than those who did not have the surgery (45.6% vs. 33.1%). Women reporting hysterectomies were also more likely to have had at least one abortion in their lifetime (46.2% vs. 31.4%, p < .01), and more likely to have used a contraceptive other than the one qualifying them for inclusion in the study (57.3% vs. 44.8%, p < .01).

Table 6. Characteristics of women according to hysterectomy status.

Ectopic pregnancy results

Ectopic pregnancy incidence

A total of 75 ectopic pregnancies (22/100,000 women years of follow-up) after their IP were reported by women surveyed in this study (). The QS cohort accounted for two-thirds (66.7%) of the reported ectopic pregnancies, with an incidence rate of 29/100,000 women years of follow-up. That rate was significantly higher than the corresponding rate in the IUD comparator group (13.8/100,000 women years of follow-up; p < .05). The median time between procedure and ectopic pregnancy, among women who experienced these events, was 4 years overall (4.5, 4.0 and 1.4 years for the QS, IUD and TL cohorts, respectively).

Table 7. Ectopic pregnancies reported, incidence rates and hazard ratios.

Retrospective calculations indicate that the reported number of ectopic pregnancies provide 80% power to detect a hazard ratio of 1.9.

Ectopic pregnancy survival analysis

Unadjusted CPH analysis found the risk of an ectopic pregnancy over the follow-up period among women treated with QS to be roughly double that of the women choosing IUDs for long-term contraception (HR = 2.1, 95% CI = 1.3–3.5, p < .01). However, introduction of the PS as a covariate in the CPH model to control for differences in women’s baseline characteristics yielded an adjusted HR of 1.4 (95% CI = 0.7–2.4, p = .3). No significant excess risk of ectopic pregnancy was associated with QS when compared to women who had undergone TL.

Characteristics of women with and without ectopic pregnancies

Average numbers of pregnancies were similar between women with and without ectopic pregnancies (4.9 in each group), although the distribution of number of pregnancies varied between the groups (p < .01). Particularly notable is the higher proportion of those experiencing ectopic pregnancies who reported five or more pregnancies (54.0% vs. 33.3% of women with no ectopic pregnancy) ().

Table 8. Characteristics of women according to ectopic pregnancy status.

In contrast to its higher proportion of women with five or more pregnancies, average parity in the ectopic pregnancy group was slightly lower than that of women without ectopic pregnancies (3.2 vs. 3.5, p < .01). The distribution of live births also differed between the two groups (p < .01). While barely one fourth (24.4%) of women experiencing ectopic pregnancies had four or more live births, the corresponding proportion among women with no ectopic pregnancies was 43.9%.

The proportion of women reporting ectopic pregnancies who used contraceptives other than their qualifying procedure was one third higher than in the group with no reported ectopic pregnancy (60.0% vs. 44.9%, p < .01). Lifetime use of birth control pills was reported by four (5.3%) of the 75 women reporting ectopic pregnancies and 550 (2.6%) of all others.

More than three-fourths (77.2%) of all QS recipients in this study had two or more insertions. While the distribution of QS users with no ectopic pregnancy who received one vs. two or more insertions mirrored the distribution in the overall QS cohort, the sub-group of QS users reporting ectopic pregnancies were more likely to have received only one insertion (36% vs. 22.8%, p < .05) ().

Table 9. Ectopic pregnancy status according to number of QS insertions.

Discussion

Findings and interpretations

Controlling for differences in baseline characteristics of women choosing to use QS vs. IUD or TL for long-term contraception, analysis of an average 16 years of follow-up data from this large population of rural Vietnamese women found no excess risk of hysterectomy among the QS cohort compared to the IUD or TL users. Neither was there any significant difference between cohorts with regard to risk of ectopic pregnancy throughout the average 16 years of follow-up, after controlling for variations in personal baseline characteristics.

Elevated likelihood of hysterectomy has been previously linked to intense bleeding, uterine fibroids, high parity, and history of TL, among other factors [Citation30,Citation31].

Higher rates of ectopic pregnancy have been associated with low socioeconomic status, older age, prior spontaneous or medically induced abortion, previous ectopic pregnancy, history of long-term contraceptive use (including IUD use prior to or at the time of conception), and TL. Despite the number of factors found to be associated with ectopic pregnancy, an estimated 50% of these rare events occur in women with none of the established risk factors [Citation32–35].

Roughly 1.5% of the women interviewed in this study reported hysterectomies during the average 16 years following their qualifying contraceptive procedure (314 hysterectomies among 21,037 women). Proportions reported in the QS and IUD cohorts (1.6 and 1.2%, respectively) are similar to those reported by Sokal et al., in their 10-year follow-up with a smaller subset of women who participated in the Vietnamese clinical trial (weighted proportions of 1.2 and 0.8%, respectively) [Citation8]. Consistent with other research, the hysterectomy incidence rate was highest among women who had undergone TL (151/100,000 women years of follow-up) [Citation36,Citation37]. Women in this study reported typical reasons for their hysterectomies (e.g., uterine fibroids, uterine/cervical polyps and menorrhagia), and also exhibited personal/health characteristics known to be associated with hysterectomies (e.g., high parity and history of TL) [Citation30,Citation31]. While uterine fibroids were identified as the reason for hysterectomy in the vast majority (roughly 90%) of responses to the specific question on this topic, it is also noted that roughly 18% of women who had hysterectomies reported experiencing menorrhagia after their IP. Although menorrhagia is also a common reason for hysterectomy, it might have been considered a symptom of one or more of the conditions more frequently cited in response to the question, and therefore less frequently reported as the specific reason for hysterectomy.

Ectopic pregnancies were reported by 0.4% of all women surveyed, and the incidence rate was 21.7/100,000 women years of follow-up. While slightly lower in absolute terms, the relative proportions in the QS and IUD cohorts (0.5 and 0.2%) are similar to those reported in Sokal et al.’s 10-year follow-up of QS in Vietnam [Citation10]. The ectopic pregnancy rate among QS users (29/100,000 women years of follow-up) was similar to the finding in Hieu and Luong’s report on ectopic pregnancies among Vietnamese QS users, although the rates in the IUD and TL cohorts were lower than in that earlier study [Citation9].

The more balanced risk of ectopic pregnancy between QS and IUD users in this study, after controlling for differences in women’s baseline characteristics in the CPH model, suggests that QS users’ higher risk of ectopic pregnancy identified in the unadjusted model was likely due to factors other than the selected contraceptive method. Some previously identified risk factors for ectopic pregnancy are also seen among women in this study. As previously described, a significantly higher proportion of the QS cohort had used other contraceptive methods in their lifetimes, compared to the IUD or TL cohorts. They also had more pregnancies, births and abortions than women in the comparator cohorts. The collected data do not identify whether previous contraceptive methods included IUD use, although given their high prevalence in Vietnam during the time of the study cohorts’ IPs [Citation38] it is likely that some portion of women in the QS group had attempted to use an IUD at some point prior to their QS procedure. These findings suggest that other available contraceptive methods had failed those women. Those circumstances might have contributed to their higher reported lifetime ectopic pregnancy rates, while also motivating them to choose QS. Further, it has been suggested that while successful use of contraceptives is effective for prevention of intrauterine as well as ectopic pregnancies, pregnancies resulting from contraceptive failure could be more likely to be ectopic [Citation33]. Relatedly, Hieu et al. reported a substantially increased probability of contraceptive failure with only one QS insertion, which suggests that strict adherence to the protocol of two QS insertions would be expected to reduce the incidence of ectopic pregnancies among QS users [Citation7]. Consistent with Hieu et al.’s reporting, the disproportionately high number of QS users with ectopic pregnancies who reported only one QS insertion could provide another likely reason for the excess risk of ectopic pregnancy in the group.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Study strengths

Data for this study are from the largest interview-based epidemiological study of QS-treated women in the world, to date. All women exposed to QS in four northern Vietnamese provinces (N = 11,107) were identified from health clinic records. Women from the same clinic areas who received IUD insertions or TL, during the same time periods and at similar ages, were comparators. A total of 21,037 completed interviews eligible for analysis, with a mean respondent follow-up in excess of 16 years, provided adequate data from which to observe the outcomes of interest. The 10,503 interviews of women (or, in a few cases, their surrogates) treated with QS represented roughly one-fifth of all those who participated in Vietnam’s clinical trial of QS.

Interviewers drawn from local health clinic staffs were valuable assets of the study. Initially, their familiarity with the community health system was instrumental in achieving the survey’s 95% response rate. Subsequently, although only a small number of events could be verified via hospital records, the Vietnam staff’s ability to verify potential outcomes of interest and clarify anomalies identified in the digitised interview data instilled a high level of confidence in the study findings.

Exhaustive sensitivity analyses detected no biases resulting from disparate locations and interviewers nor from an unexpected deviation from the prescribed matching procedure in one province.

Study weaknesses

Identification of potential IUD subjects in Nam Dinh via community survey, rather than from logbooks as was done in the other provinces, may have resulted in omission of some women from that comparator pool who were ill or dead at the time of the study. Because roughly half the interviewed women came from Nam Dinh, and the alternate identification method occurred only in the IUD group, this sampling bias may have underestimated the number of hysterectomies and ectopic pregnancies in the IUD cohort. A bias towards comparators who were alive, healthy, and/or otherwise readily available for interview was also introduced by allowing interviewers to select which subject to interview, from each pair of potential IUD comparators in Nam Dinh. Lacking data about women not interviewed from the IUD pool precluded analysing the exact consequences of this selection system, although the expectation would be an interviewed group of IUD women who were healthier than the QS group. While acknowledged as a limitation, this bias would only tend to overestimate the relative long-term risks of hysterectomy and ectopic pregnancy in the QS cohort. Since adjusted results found no significant excess risk in the QS group, for either outcome, it can be concluded that any bias introduced by the subject selection method in Nam Dinh is not relevant to the conclusions of this analysis.

Another study limitation was a lack of hospital records for outcomes adjudication. While the study protocol called for hospital verification of all outcomes, shortage of space in Vietnamese hospitals translated into missing records for most events. Nonetheless, 49 outcomes were adjudicated from hospital records, including 27 of the reported hysterectomies and one ectopic pregnancy. Among outcomes that could be checked in this way, discrepant event dates were the most common inconsistencies identified between interview and hospital data. While suggestive of potential recall bias, sensitivity analysis indicated that the distribution of mismatched dates did not favour one cohort or the other. Furthermore, notwithstanding some incorrectly recalled dates, the reported events were confirmed to have occurred at some point during the follow-up period. In addition, findings were further substantiated by review of all interview outcomes and verification by local clinics.

With regard to the IUD cohort, and consistent with the cohort’s average age of 51 years at the time of their interviews, more than half the group reported being post-menopausal and therefore unlikely to be still using any method of birth control.

Differences in results and conclusions

This study’s findings are fairly consistent with previous reports of hysterectomies and ectopic pregnancies among women choosing QS, IUD or TL for long-term contraception. The large number of women surveyed allows for assignment of statistical significance to the results.

Relevance of the findings: implications for clinicians and policymakers

Controlling for baseline differences in characteristics of women choosing the three different forms of long-term contraception, no excess risk of hysterectomy or ectopic pregnancy was found in women selecting QS vs. IUD or TL in a large cohort of rural Vietnamese women during an average 16-year follow-up period. These findings complement previous findings of no excess risk of reproductive cancer associated with QS in this study population [Citation6] and further assuage speculation regarding health risks associated with the use of QS for permanent contraception.

Unanswered questions and future research

Clinical trials of QS, with carefully designed patient follow-up, will provide more specific details regarding the relationship between QS and women’s reproductive health. Optimally, further understanding of the risks and benefit of these contraceptive procedures would be enhanced by a detailed longitudinal history and analysis of events preceding and following the particular contraceptive’s use in individual women. It is possible that more detailed information on the sequence of different types of events and/or contraceptive use could provide more insight regarding the findings in this very large cohort study.

Conclusions

After accounting for differences in personal baseline characteristics, this large retrospective cohort study found no significant excess long-term risk of either hysterectomy or ectopic pregnancy among women exposed to QS, when compared to matched cohorts of IUD and TL users. Identification and interview of more than 21,000 QS, IUD and TL users with an average follow-up exceeding 16 years, coupled with local clinic staffs’ personal knowledge of survey participants, allowed adequate time for development of procedure-related outcomes and the ability to verify survey responses. The findings reported herein provide further support for use of QS as a safe method of non-surgical permanent contraception.

Supplementary material

Download PDF (84.4 KB)Disclosure statement

ISAF had sponsored previous reproductive research in Vietnam and other countries and had an impact on the selection of sites for this study. Originally ISAF hired a Contract Research Organization (CRO) to operationalise the study, and the authors were requested to design the study, design and carry out the analysis, and publish the report. Subsequent to the start of the study, ISAF took over the CRO functions. They also reviewed and provided comments on the study report and draft manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Women surveyed for this study were part of a large field trial that included more than 1300 clinicians in 24 provinces and resulted in approximately 55,000 QS cases. Most of the 11,105 QS procedures (97.5%) performed in the four provinces included in this study had been completed by the end of 1992, and another 4% (449 cases) in 1993. Although the Vietnamese government halted the trial at the end of 1993 and recalled the small quantities of quinacrine pellets that had not been administered to women, clinic records identified 33 additional procedures performed in these provinces between 1994 and 1996. Based on discussions with the study sponsors, who have extensive history with the reproductive health community in Vietnam, it appears that some physicians in the rural areas kept their remaining small supplies of QS pellets and used them to perform the additional procedures in 1994–1996.

2 International Services Assistance Fund (ISAF), 104 T.W. Alexander Drive, Bldg. 1, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709.

3 Physicians working at the provincial/district levels of Vietnam’s reproductive health system were trained to conduct all interviews for the survey. Use of physicians as interviewers was intended to enhance women’s comfort levels when discussing their health, and also to make certain that appropriate follow-up questions would be used to ensure that the women surveyed were properly citing cancer diagnoses. In addition, employing physicians trained consistently in interview procedures was also intended to minimise any possible effect on survey results from use of multiple interviewers.

4 This review entailed modelling multiple scenarios that would reveal different biases in all stages of data collection.

References

- Institute for Development Training. Female voluntary non-surgical sterilization: the quinacrine method. Module 12 of Training Course in Women’s Health. Chapel Hill (NC): IDT; 1996.

- Growe RG, Luster MI, Fall PA, et al. Quinacrine-induced occlusive fibrosis in the human fallopian tube is due to a unique inflammatory response and modification of repair mechanisms. J Reprod Immunol. 2013;97:159–166.

- Oanh TTM, Tien TV, Luong DH, et al. Assessing provincial health systems in Vietnam: lessons from two provinces. Bethesda (MD): Abt Associates Inc.; 2009.

- Cancel AM, Dillberger JE, Kelly CM, et al. A lifetime cancer bioassay of quinacrine administered into the uterine horns of female rats. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2010;56:156–165.

- Haseman JK, Growe RG, Zeiger E, et al. A critical examination of the mode of action of quinacrine in the reproductive tract in a 2-year rat cancer bioassay and its implications for human clinical use. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015;71:371–378.

- Jones JK, Tave A, Pezzullo JC, et al. Long-term risk of reproductive cancer among Vietnamese women using the quinacrine hydrochloride pellet system vs. intrauterine devices or tubal ligation for contraception. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2017;22:123–130.

- Hieu DT, Tan TT, Tan DN, et al. 31,781 cases of non-surgical female sterilisation with quinacrine pellets in Vietnam. Lancet. 1993;342:213–217.

- Sokal DC, Hieu DT, Weiner DH, et al. Long-term follow-up after quinacrine sterilization in Vietnam. Part II: interim safety analysis. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:1092–1101.

- Hieu DT, Luong TT. The rate of ectopic pregnancy for 24,589 quinacrine sterilization (QS) users compared to users of other methods and no method in 4 provinces in Vietnam, 1994–1996. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83(2):S35–S43.

- Sokal DC, Hieu DT, Loan ND, et al. Safety of quinacrine contraceptive pellets: results from 10-year follow-up in Vietnam. Contraception. 2008;78:66–72.

- Feldblum PJ, Wheeless A, Trujillo V, et al. Pelvic surgery and hospitalization among Chilean women after nonsurgical sterilization with quinacrine pellets between 1977 and 1989. Contraception. 2012; 86:106–109.

- Anh DN, Tacoli C, Thanh HX, Migration in Vietnam, A review of information on current trends and patterns, and their policy implications. Paper presented at: Regional Conference on Migration, Development and Pro-Poor Policy Choices in Asia. 2003 June 22–24; Dhaka, Bangladesh. [cited 2017 July 26]; Available from: http://www.eldis.org/vfile/upload/1/document/0903/Dhaka_CP_7.pdf

- Westman J, Hampel H, Bradley T. Efficacy of a touchscreen computer based family cancer history questionnaire and subsequent cancer risk assessment. J Med Genet. 2000;37:354–360.

- Peipert JF, Gutmann J. Oral contraceptive risk assessment: a survey of 247 educated women. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:112–117.

- Michels KB, Willett WC, Rosner BA, Manson JE, et al. Prospective assessment of breastfeeding and breast cancer incidence among 89,887 women. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1996;51:468–469.

- Shlay JC, Dunn T, Byers T, et al. Prediction of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2–3 using risk assessment and human papillomavirus testing in women with atypia on papanicolaou smears. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2001;56:87–88.

- Kindermann G, Maassen V, Kuhn W. Laparoscopic management of ovarian tumors subsequently diagnosed as malignant: a survey from 127 German departments of obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1998;53:212–213.

- Murff HJ, Byrne D, Syngal S. Cancer risk assessment: quality and impact of the family history interview. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:239–245.

- Hughes KS, Roche C, Campbell CT, et al. Prevalence of family history of breast and ovarian cancer in a single primary care practice using a self-administered questionnaire. Breast J. 2003;9:19–25.

- McWilliams RR, Rabe KG, Olswold C, et al. Risk of malignancy in first-degree relatives of patients with pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:388–394.

- Hall IJ, Burke W, Coughlin S, et al. Population-based estimates of the prevalence of family history of cancer among women. Community Genet. 2001;4:134–142.

- Euhus DM, Leitch AM, Huth JF, et al. Limitations of the Gail model in the specialized breast cancer risk assessment clinic. Breast J. 2002;8:23–27.

- Lee JS, John EM, McGuire V, et al. Breast and ovarian cancer in relatives of cancer patients, with and without BRCA mutations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:359–363.

- Rauscher GH, Sandler DP, Poole C, et al. Family history of cancer and incidence of acute leukemia in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:517–526.

- Walter FM, Emery J. ‘Coming down the line’ – patients’ understanding of their family history of common chronic disease. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:405–414.

- Lamon JM. Cancer surveillance. Who stands to benefit? Postgrad Med. 1985;78:55–8, 63–70.

- Spangler E, Zeigler-Johnson CM, Malkowicz SB, et al. Association of prostate cancer family history with histopathological and clinical characteristics of prostate tumors. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:471–474.

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55.

- D’Agostino RB. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265–2281.

- Aziz S. Indication of emergency hysterectomy in Pakistani patients. J Soc Obstet Gynaecol Pakistan. 2017;7:45–49.

- Heinonen PK, Helin R, Nieminen K. Long-term impact and risk factors for hysterectomy after hysteroscopic surgery for menorrhagia. Gynecol Surg. 2006;3:265–269.

- Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Gracia CR, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy in women with symptomatic first-trimester pregnancies. Fertil Steril. 2006; 86:36–43.

- Li C, Zhao WH, Meng CX, et al. Contraceptive use and the risk of ectopic pregnancy: a multi-center case-control study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115031.

- Tahmina S, Daniel M, Solomon P. Clinical analysis of ectopic pregnancies in a tertiary care centre in southern India: a six-year retrospective study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:QC13–QC16.

- Karaer A, Avsar FA, Batioglu S. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: a case-control study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;46:521–527.

- Templeton AA, Cole S. Hysterectomy following sterilization. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1982;89:845–848.

- Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Tylor LR, et al. Higher hysterectomy risk for sterilized than nonsterilized women: findings from the U.S. collaborative review of sterilization. The U.S. collaborative review of sterilization working group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:241–246.

- Hieu DT, Van HT, Donaldson PJ, et al. The pattern of IUD use in Vietnam. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 1995;21:6–10.