Abstract

Purpose: This study aimed to explore the prescription of different contraceptive methods to Swedish women with obesity and to compare the pattern of prescription and adherence to treatment between this group and normal-weight women.

Materials and methods: This study included 371 women with obesity and 744 matched normal-weight women, aged 18–40. Medical records were scrutinised for the period 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2014. The retrieved variables included: background characteristics, prescribed contraceptive methods, adverse effects, duration of treatment, reason for discontinuation and bleeding pattern.

Result: Progestin-only pills were mainly prescribed to women with obesity (44% vs. 20%, p = 0.001) whereas combined hormonal contraception was mainly prescribed to normal-weight women (60% vs. 21%, p < 0.0001). Thirty-three percent vs. 25% (p = 0.003) discontinued their contraceptive method within 1 year. The most commonly declared reason for discontinuation was bleeding disturbance (14.7% vs. 9.6%, p = 0.008).

Conclusion: The most commonly prescribed contraceptive method in women with obesity was progestin-only pills, but surprisingly many women with obesity were prescribed combined hormonal contraception despite current Swedish and European guidelines. Incident users with obesity were significantly more likely to discontinue their contraceptive method within the first year of the study period, compared with incident normal-weight users.

摘要:

目的:本研究旨在探讨瑞典肥胖女性不同的处方避孕方法, 并与体重正常女性的避孕方法和续用情况进行比较。

材料和方法:这项研究包括371名肥胖女性和744名体重正常的女性, 年龄在18-40岁之间。临床观察时间为2010年1月1日至2014年12月31日。涉及的变量包括:背景特征、规定的避孕方法、副作用、治疗持续时间、停药原因和出血模式。

结果:单纯孕激素避孕药主要用于肥胖女性(44% vs. 20%, p = 0.001), 而复方激素避孕药主要用于正常体重女性(60% vs. 21%, p < 0.0001)。两组中在一年内停药的女性分别是:33%及25% (p = 0.003)。停药最常见的原因是月经紊乱(14.7% vs. 9.6%, p = 0.008)。

结论:肥胖女性最常用的处方避孕方法是应用单纯孕激素避孕药, 尽管瑞典和欧洲现行的指南已经指出, 但出乎意料的是许多肥胖女性却在应用复方激素避孕药。与体重正常的女性相比, 肥胖的女性在研究期间的第一年更有可能停药。

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity is increasing all over the world [Citation1]. In 2016, more than 650 million adults were obese [Citation2]. Eight percent of Swedish women aged 16–29 and 14% aged 30–44 were obese in 2018 [Citation3].

Many women of reproductive age thus are obese and in need of a safe and effective contraceptive method, but so far little is known about contraceptive use by women with obesity.

Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) are the most commonly used contraceptive methods in Sweden [Citation4]. Approximately, 80% of Swedish women are supposed to be ever users of combined oral contraceptives (COC) [Citation5]. During the last 15 years, however, the pattern of contraceptive use has changed and progestin-only methods and intrauterine contraception have become more common. The use of progestin-only pills (POPs) is far more common in Sweden than in other parts of the world [Citation6,Citation7].

Obesity is classified into three subgroups: obesity class I (BMI 30–34.9), obesity class II (BMI 35–39.9) and obesity class III (BMI > 40) [Citation2]. People with obesity seem to have a 2–4-fold increased risk of venous thromboembolism [Citation8–10]. This risk is further increased if a woman with obesity uses CHCs [Citation9]. Therefore, the guidelines of the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care (ESC), as well as the Swedish guidelines, state that CHCs should only be used if no other methods are acceptable, or if the benefits outweigh the risks [Citation11,Citation12]. Instead, these women should be recommended POPs, subcutaneous implants, levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) or non-hormonal birth control methods [Citation11,Citation12]. Despite these recommendations, there are few studies investigating the prescription of contraceptives, the adherence to treatment, and possible side effects of these methods among women with obesity.

The pharmacokinetic profile of COC in women with obesity has been reported to differ from normal-weight women, but ovulation seems to be adequately suppressed in COC users with obesity [Citation13–15]. Several studies, including a Cochrane Review from 2016, have concluded that the evidence did not generally show an association between BMI and the effectiveness of hormonal contraceptives [Citation13,Citation16,Citation17]. However, even if differences in pharmacokinetic profiles do not seem to result in ovulation or unintended pregnancies [Citation14,Citation18,Citation19], a substantial number of women with obesity using COC seem to have considerable ovarian follicular activity [Citation15]. Edelman et al. [Citation15] found that a majority of women with obesity using COC had evidence of poor end-organ suppression, although they had no overt evidence of ovulation.

This difference in follicular suppression and activity could possibly cause differences in bleeding pattern, which in turn could affect satisfaction with and adherence to treatment.

The side effect profile, including poor bleeding control, has been described as one of the most important features of a contraceptive method [Citation20]. Progestin-only methods are more likely to induce bleeding disturbances [Citation21–23] and have been reported to have lower continuation rates [Citation6]. It is therefore necessary to study the side effects experienced by POP users with obesity, for which CHCs are not primarily recommended. More studies including women with obesity are needed in order to find a basis for correct and adequate information, and consequently to optimise the contraceptive counselling in this increasing group of women.

Aim

This study aimed to explore the prescription of different contraceptive methods to women with obesity and to compare the patterns of prescription and adherence to treatment between this group and normal-weight women. We also aimed to investigate whether women with obesity using hormonal contraceptives report more side effects and poor bleeding control to the care giver compared with normal-weight women, and whether these reported side effects result in more frequent contact with healthcare providers.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a retrospective cohort study. Medical records of the included study participants from the period of 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2014 were scrutinised.

Study objects

We included women aged 18–40, with 30 ≤ BMI ≤ 50 who had visited the family planning units in the county of Östergötland, Sweden, at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Linköping University Hospital, at least once during the year of 2010. The catchment area includes both urban and rural populations. We decided to exclude women with a BMI >50 because of uncertain weight data (n = 19).

All included women had to have a Swedish personal identification number (PIN). Every woman with obesity was matched to two normal-weight women (19 ≤ BMI < 25) born on the same day or, if no women were found, born on the following day or days. The matched normal-weight women had been in contact with the same family planning units for contraceptive counselling at least once during 2010. Emigrated, deceased or women who were confirmed to have moved outside the catchment area during the study period were not included in the analysis.

Collection and processing of data

Data were collected from the computerised medical record system Obstetrix® (Cerner AB, Sweden) and Cosmic® (Cambio Healthcare systems, Sweden). In order to anonymise the study objects, all PINs were replaced by a code number.

From the Obstetrix® medical record system, the retrieved variables were as follows: year of birth, age, BMI at the beginning of the study period, BMI at the end of the study period, other diseases, all contraceptive methods prescribed to the woman during the study period and the associated duration of treatment, adverse effects, reasons for discontinuation, and bleeding pattern. Prescription data were used as a proxy for drug use. The total number of visits, total number of previous pregnancies and year of last prescription during the study period were also retrieved.

All information on prescribed contraceptives was then verified with information from the pharmacological prescription module in Cosmic®

We distinguished between incident and prevalent users. An incident user was defined as a study object that had not used any type of contraception for the last 6 weeks or more at the start of the study period on 1 January 2010. A prevalent user was defined as a study object that was using some type of contraception at the start of the study period on 1 January 2010.

Statistical analysis

We performed a sample size calculation based on the assumption that 15% of the normal-weight women would discontinue use or change contraceptive method during the first year of the study period. We considered a 50% higher rate of discontinuation among women with obesity clinically significant, i.e., that 22.5% of the women with obesity would discontinue or change method within 1 year. To detect this difference with 80% power and a significance level of 0.05, we needed to include 300 women with obesity and 600 normal-weight women. The number of women with obesity who were found to have had at least one contact with the family planning unit during 2010 only slightly exceeded this number. We therefore decided to include all women with obesity in the study, together with twice as many normal-weight women.

Data from the medical records were converted into numerical variables and put together in Microsoft Excel® 2010. The data were then transferred into IBM SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM, New York, NY) where statistical analyses were performed. Chi-square tests were used to estimate differences in prescription of contraceptive methods between different groups, as well as to make comparisons regarding bleeding pattern and discontinuation of contraceptive use. When analysing the reason for discontinuation of contraceptive use, infrequent reasons for discontinuation were combined as ‘other’ in order to enable comparisons between the two BMI groups. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant throughout the study.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved on 26 April 2017 by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Linköping, Sweden (No. 2017/180-31).

Results

The study population consisted of 1115 women in total; 371 with obesity and 744 normal-weight women. Their background characteristics are presented in .

Table 1. Background characteristics, contraceptive use and contacts in the 1115 included women.

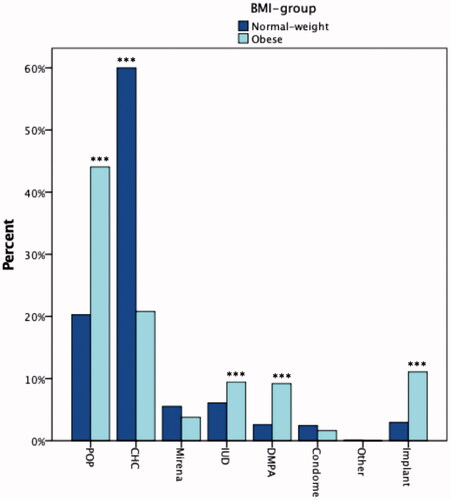

CHCs were mainly prescribed to normal-weight women (60% vs. 21%, p < 0.0001) whereas the POP was mainly prescribed to women with obesity (44% vs. 20%, p = 0.001) Use of Cu-IUD, implant and depomedroxyprogesteroneacetat (DMPA) were significantly more common in women with obesity ().

Figure 1. First prescribed contraceptive method during the study period. Normal weight women n = 739. Women with obesity n = 370. CHC: combined hormonal contraceptives; DMPA: depomedroxyprogesteroneacetate (injection); IUD: intrauterine device; POP: progestin-only pills. ***p < 0.001 calculated by chi-square test and adjusted with Bonferroni method.

There was no significant difference in the number of different prescribed contraceptive methods between the groups during the 5-year study period (). The overall duration of use did not significantly differ between the BMI-groups. Discontinuation of any method over the whole 5-year study period was more common among incident than prevalent users (88% vs. 68%, p < 0.001).

During the entire 5-year study period 273 obese (73%) and 551 normal-weight women (74%) discontinued their first registered contraceptive method, but during the first year 33% of the women with obesity discontinued compared with 25% of the normal-weight women (p = 0.003). When stratified for incident and prevalent users, the difference remained significant among incident users only (46% vs. 34%, p = 0.029).

Within the whole population, POP users (n = 313) were more likely than CHC users (n = 521) to discontinue within the first year (35% vs. 18%, p < 0.001). The difference remained significant when stratified for incident (55% of POP users compared with 34% of CHC users, p = 0.001) and prevalent (23% vs. 14%, p = 0.005) users. Among POP users, women with obesity and normal-weight women showed equal discontinuation rates.

A second contraceptive method was prescribed to 54% of the women with obesity and 53% of the normal-weight women who discontinued their first method during the study period. Among these, the POP was the most prescribed second contraceptive method in both women with obesity (35%) and normal-weight women (38%) followed by CHCs (19% vs. 29%) and LNG-IUS (16% vs. 15%).

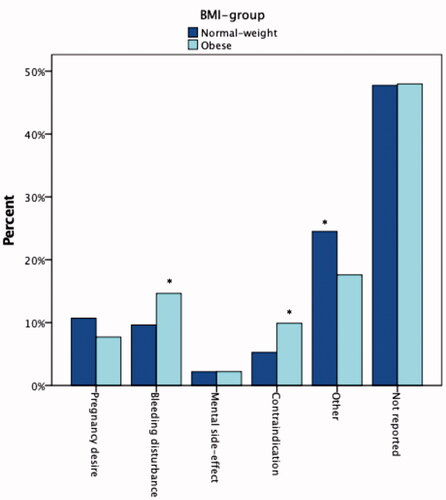

The most commonly declared reason for discontinuation of the first contraceptive method was bleeding disturbance; 14.7% of women with obesity and 9.6% of normal-weight women (p = 0.008) declared this as their main reason for discontinuation (). However, the reason for discontinuation was not mentioned in the patient records in 48% of all women, without any difference between the groups.

Figure 2. Reported reason for discontinuation of first prescribed contraceptive method during the study period. Normal weight women n = 551. Women with obesity n = 273. ‘Other’ includes skin problems, dysmenorrhoea, weight gain, fear, unspecific pain and miscellaneous reasons. *p < 0.01 calculated by chi-square test and adjusted with Bonferroni method.

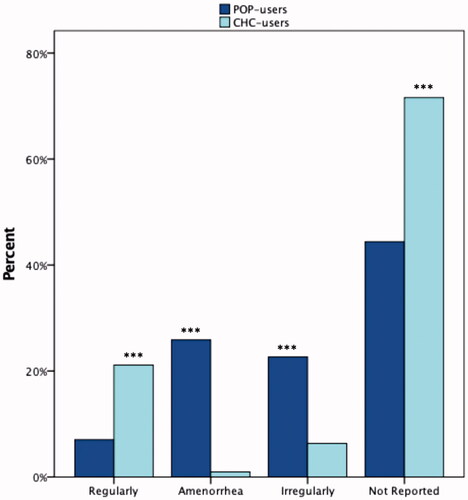

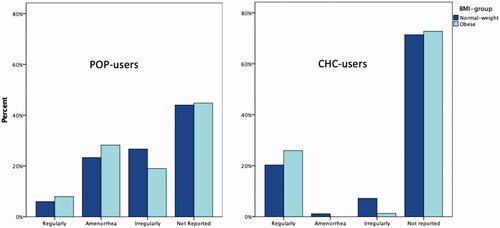

POP users reported significantly more irregular bleedings and amenorrhoea compared with CHC-users (). There was no significant difference in reported bleeding pattern between normal-weight-women and women with obesity using either CHCs or POPs ().

Figure 3. Reported bleeding pattern among women using progestin-only pills (POP) (n = 313) or combined hormonal contraceptives (CHC) (n = 521) as the first prescribed contraceptive method during the study period. ***p < 0.001 calculated by chi-square test and adjusted with Bonferroni method.

Figure 4. Reported bleeding pattern among women using progestin-only pills (POP) and combined hormonal contraceptives (CHC) as the first prescribed contraceptive method during the study period. To the left POP-users (women with obesity n = 163, normal-weight n = 150). To the right CHC-users (women with obesity n = 77, normal-weight n = 444).

In order to further analyse contraceptive use by the women with obesity, we divided this group of women into two subcategories; BMI class I (n = 264) and BMI class II–III (n = 107). The most prescribed contraceptive in the group of women with BMI class II–III was the POP, (56.1%), followed by Cu-IUD and DMPA (each 12.1%), the progestogen only implant (11.2%) and the LNG-IUS (4.7%). There were only three women in this group that used CHCs.

Among women with BMI class I, 74 women (28%) were CHC users whereof 88% were prevalent users.

Twenty-four CHC users (32%) in the BMI class I group and one CHC user in the BMI class II-III group discontinued their use because the prescriber considered the woman’s BMI to be a contraindication.

Discussion

Findings and interpretation

Forty-four percent of the women with obesity were prescribed the POP which makes it the most commonly prescribed method in this group. Our hypothesis was thereby confirmed. Twenty percent of normal-weight women were prescribed the POP, which also confirms the previously reported high prevalence of POP use in Sweden [Citation6]. Even though the POP was the most prescribed contraceptive method to women with obesity, a surprisingly high number of women in this group (21%) were prescribed CHCs during the study period. This figure is even higher than in a previously reported study from our group [Citation24] despite the recommendations that CHCs should only be prescribed with caution to this group of women according to both Swedish and European guidelines [Citation11,Citation12]. These recommendations were issued in 2014–2015, i.e., before the study period. The Swedish recommendations during the study period were even stricter with a ‘sharp limit’ of BMI 30 to prescribe CHC [Citation25].

The majority of these women were within BMI class I and most were prevalent CHC users. We may speculate that these women had a lower BMI when the first CHC prescription was filled, thus before the study period. Other progestin only methods and Cu-IUD were significantly more common among women with obesity. This most probably reflect that most prescribers are aware of current recommendations to avoid CHC, although many women with obesity were prescribed CHC. It can be noted that the prescription of DMPA was surprisingly high to women with obesity, despite the risk of weight gain [Citation26].

The number of included women using LARC was low. We included women during 1 year (2010) and this means that prevalent LARC-users, i.e., users who had an IUD/LNG-IUS or an implant inserted before the study period, are missing since they do not show up for regular visits and do not have a need of an annual prescription. We can assume that the actual number of LARC users in the population is substantially higher [Citation4].

Both groups showed similar average duration of treatment of first method during the whole study period, corresponding to that the discontinuation of treatment did not differ during the whole 5-year study period. However, among incident users, women with obesity were significantly more likely to discontinue their contraceptive method within the first year of the study period. There reason for this finding is unclear. It has previously been shown that women with obesity may have lower socioeconomic status than normal weight women [Citation27]. It might be speculated that this might be followed by an increased vulnerability which here is reflected in a higher discontinuation rate during the first year of use. Irrespective of BMI, POP users discontinued their contraceptive use more often than CHC users, in accordance with previous studies [Citation6]. This might be explained by the well-known fact that POP users reported bleeding disturbances more often than CHC users. As expected, the prevalent users were more likely to adhere to their method than the incident users.

POP use was more common among women with obesity. Even though women with obesity using POPs did not show an increased risk of an irregular bleeding pattern compared with normal-weight women using POPs, women with obesity were more prone to discontinue due to reported bleeding disturbances. It should be kept in mind that the reasons for discontinuation were not mentioned in the records by almost half of the women, and bleeding problems might have been under-reported. However, there was no difference in lack of information in the medical records between the groups and we do not believe that this factor biased the comparisons between the groups.

The frequency of discontinuation during the entire study period was similar among women with obesity and normal-weight women regardless of contraceptive method, perhaps indicating that the frequency of side effects in general does not differ among women in different BMI categories. Over the whole 5-year study period, the high discontinuation rates reflect the high use of oral contraceptives. Trussel et al. reported that every third women using oral contraceptives discontinued within 1 year [Citation28].Therefore, it seems reasonable that almost 75% of women in fertile ages discontinue within a 5-year period .

Strength and weaknesses

The study design with matched cohorts is an appropriate method in a retrospective study based on medical records. The equal distribution of nulligravidae in the two groups strengthens the assumption that other patterns related to family planning are equally distributed and any differences in contraceptive use can be assumed to be caused by factors related to the BMI. The study is based on available data registered in the patient records. The access to two different medical records (Obstetrix® and Cosmic®) validated the registered information regarding contraceptives with actual prescriptions.

The prospective collection of information in the records strengthens the reliability. In Sweden, midwives prescribe approximately 85% of all contraceptives. In the catchment area, almost all prescriptions are made by midwives and gynaecologists in public health care with the same patient record systems. Consequently, we believe that the design of the present study covers the vast majority of all prescriptions of contraceptives during the study period. Prescriptions made by midwives or doctors outside these systems are negligible. However, some types of information were frequently missing, especially concerning reasons for discontinuation, and this is the greatest limitation of this study. Information was missing to the same extent in both BMI groups. It is most likely that a regular bleeding pattern in a satisfied patient is not recorded in the medical records. Therefore, we may assume that the women with no information regarding bleeding pattern were mainly women with a regular bleeding pattern or amenorrhoea.

Our sample size calculation assumed a discontinuation rate of 15 vs. 22.5% for the two BMI groups respectively. Other studies have found a discontinuation rate of 20–35% within a year [Citation6,Citation28]. Our discontinuation rate was within this range for both groups.

The high, but for Swedish standards expected number of POP users in our study enables a fair comparison with CHC users regarding adherence to treatment, side effects such as bleeding disturbances, and reasons for discontinuation.

We consider it a strength to separate prevalent from incident users in order to distinguish the patterns of prescription in relation to BMI. Since there is no general definition of incident and prevalent drug use, comparisons between studies with different definitions must be made with caution. Our definition was based on the fact that the increased risk of venous thromboembolism and any haemostatic changes caused by CHCs is reversed after 6 weeks [Citation29]. After this wash out period, the women should be considered as first time users from a risk perspective [Citation30]. This group may include both previous never-users and women who just have made a short stop in use. From a risk perspective they could be assumed as equal and were therefore all considered as incident users. However, from an adherence perspective, these groups may differ as the group we classify as incident users may include a substantial number of women with previous good experience of the contraceptive chosen. We have no way to distinguish between these groups but it cannot be excluded that this may have hampered the interpretation of the adherence as ‘true’ first time users may be more likely to discontinue within a short time frame.

Open questions and future research

This study provides new information on contraceptive use by women with obesity. This is a globally increasing population that has been identified as having an unmet need of contraception [Citation31].

The study raises the awareness of prescription routines and the adherence to current guidelines among Swedish contraceptive counsellors. Thus, it is a starting point in the pursuit of improved contraceptive counselling. Many women with obesity were prescribed CHCs despite international and national recommendations of cautious prescription. Increased awareness would undeniably facilitate the contraceptive counselling of women with obesity, both from the prescribers’ and the patient’s perspective.

Conclusion

The most commonly prescribed contraceptive method in women with obesity was progestin-only pills, but surprisingly, many women with obesity were prescribed combined hormonal contraception despite current Swedish and European guidelines. The prescription of DMPA to women with obesity was higher than expected. This may reflect difficulties in finding an appropriate method to this group of women. Incident users with obesity were significantly more likely to discontinue their contraceptive method within the first year of the study period, compared with incident normal-weight users, which may indicate an increased vulnerability.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mats Fredriksson for valuable help with the statistics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Collaboration NCDRF. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387:1377–1396.

- World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. Fact sheet. 2018 [cited 2019 April 7] https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. Så mår Sveriges befolkning. 2018 [cited 2019 April 7]. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/nyheter-och-press/nyhetsarkiv/2018/december/sa-mar-sveriges-befolkning–ny-statistik-om-folkhalsan-2018/.

- Lindh I, Skjeldestad FE, Gemzell-Danielsson K, et al. Contraceptive use in the Nordic countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96:19–28.

- Odlind VB, Milson I, Familjeplanering:preventivmetoder, aborter och rådgivning. 1st ed. Lund: Studentlitteratur AB; 2008.

- Josefsson A, Wirehn AB, Lindberg M, et al. Continuation rates of oral hormonal contraceptives in a cohort of first-time users: a population-based registry study, Sweden 2005-2010. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003401.

- Hall KS, Trussell J, Schwarz EB. Progestin-only contraceptive pill use among women in the United States. Contraception. 2012;86:653–658.

- Goldhaber SZ, Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, et al. A prospective study of risk factors for pulmonary embolism in women. JAMA. 1997;277:642–645.

- Pomp ER, le Cessie S, Rosendaal FR, et al. Risk of venous thrombosis: obesity and its joint effect with oral contraceptive use and prothrombotic mutations. Br J Haematol. 2007;139:289–296.

- Parkin L, Sweetland S, Balkwill A, et al. Body mass index, surgery, and risk of venous thromboembolism in middle-aged women: a cohort study. Circulation. 2012;125:1897–1904.

- Merki-Feld GS, Skouby S, Serfaty D, et al. European society of contraception statement on contraception in obese women. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2015;20:19–28.

- Läkemedelsverket. Antikonception-behandlingsrekommendation. Information Från Läkemedelsverket. 2014;25:14–28. Swedish.

- Westhoff CL, Torgal AH, Mayeda ER, et al. Pharmacokinetics of a combined oral contraceptive in obese and normal-weight women. Contraception. 2010;81:474–480.

- Westhoff CL, Torgal AH, Mayeda ER, et al. Ovarian suppression in normal-weight and obese women during oral contraceptive use: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:275–283.

- Edelman AB, Cherala G, Munar MY, et al. Prolonged monitoring of ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel levels confirms an altered pharmacokinetic profile in obese oral contraceptives users. Contraception. 2013;87:220–226.

- McNicholas C, Zhao Q, Secura G, et al. Contraceptive failures in overweight and obese combined hormonal contraceptive users. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:585–592.

- Lopez LM, Bernholc A, Chen M, et al. Hormonal contraceptives for contraception in overweight or obese women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;18:CD008452.

- Edelman AB, Carlson NE, Cherala G, et al. Impact of obesity on oral contraceptive pharmacokinetics and hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian activity. Contraception. 2009;80:119–127.

- Westhoff CL, Torgal AH, Mayeda ER, et al. Pharmacokinetics and ovarian suppression during use of a contraceptive vaginal ring in normal-weight and obese women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:39 e1–36.

- Kopp Kallner H, Thunell L, Brynhildsen J, et al. Use of contraception and attitudes towards contraceptive use in Swedish women – a nationwide survey. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125990.

- Zigler RE, McNicholas C. Unscheduled vaginal bleeding with progestin-only contraceptive use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:443–450.

- Belsey EM. Vaginal bleeding patterns among women using one natural and eight hormonal methods of contraception. Contraception. 1988;38:181–206.

- Broome M, Fotherby K. Clinical experience with the progestogen-only pill. Contraception. 1990;42:489–495.

- Ginstman C, Frisk J, Ottosson J, et al. contraceptive use before and after gastric bypass: a questionnaire study. Obes Surg. 2015;25:2066–2070.

- Läkemedelsverket. Antikonception – Behandlingsrekommendation. Information från läkemedelsverket. 2005;16(7):7–84. Swedish.

- Dianat S, Fox E, Ahrens KA, et al. Side effects and health benefits of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:332–341.

- Lindh I, Hognert H, Milsom I. The changing pattern of contraceptive use and pregnancies in four generations of young women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95:1264–1272.

- Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83:397–404.

- Winkler UH. Hemostatic effects of third- and second-generation oral contraceptives: absence of a causal mechanism for a difference in risk of venous thromboembolism. Contraception. 2000;62:11S–20S. discussion 37S-38S.

- Rabe TL, Ludwig M, Dinger JC, et al. Contraception and thrombophilia – a statement from the German Society of Gynecological Endocrinology and Reproductive Medicine (DGGEF e. V.) and the Professional Association of the German Gynaecologists (BVF e. V.). J Reprod Endokrinol. 2011;8:178–218.

- McKeating A, O’Higgins A, Turner C, et al. The relationship between unplanned pregnancy and maternal body mass index 2009-2012. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2015;20:409–418.