Abstract

Objective: The aim of the study was to provide an additional, detailed description of early bleeding patterns with the 19.5 mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS).

Methods: We conducted a pooled analysis of the bleeding diaries of participants in a previously reported phase II randomised controlled study (n = 741) and a phase III study (n = 2904), with 2-year extension phase (n = 707), of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS. Main outcome measures were the median number of bleeding and/or spotting days per 30-day reference period for 12 months and the influence of the previous contraceptive method and levonorgestrel dose on bleeding patterns.

Results: The pooled analysis comprised 1697 women. There was a progressive decline in the number of bleeding and/or spotting days from month 1: the proportion of women with ≤4 bleeding and/or spotting days per month increased from 6.2% in month 1 to 15.8% in month 2, 26.0% in month 3, 39.3% in month 6 and 54.1% in month 12. The median number of bleeding and/or spotting days in month 1 was lowest in women who had previously been using an LNG-IUS.

Conclusion: Analysis of bleeding diaries using 30-day reference periods provides detailed insight into bleeding changes in the first months following placement of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS. This insight may prove useful when counselling women about contraceptive choice and method continuation.

摘要

目的:本研究的目的是对19.5mg左炔诺孕酮宫内释放系统(LNG-IUS)早期出血模式提供一个额外的、详细的描述。

方法:我们对先前报道的II期随机对照研究(n = 741)和III期研究(n = 2904)的参与者的出血日记进行了汇总分析, 其中19.5mg LNG-IUS延为2年观察期(n = 707)。主要观察指标为12个月内每30天参考期内出血和/或点滴出血天数的中位数, 以及先前避孕方法和左炔诺孕酮剂量对出血模式的影响。

结果:汇总分析包括1697名女性。从第一个月开始, 出血和/或点滴出血的天数逐渐减少:每月有4天出血和/或点滴出血的妇女比例从第1个月的6.2%增加到第2个月的15.8%, 第3月为26.0%, 第6月为39.3%, 第12月为54.1%。第1个月出血和/或点滴出血天数的中位数在以前使用过LNG-IUS的妇女中是最低的。

结论:分析出血日记使用30天的参考期提供了详细的放置19.5mg LNG-IUS后头几个月的出血变化情况。这一见解在向妇女提供有关避孕选择和避孕方法的延续咨询时可能是有用的。

Introduction

The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) is a highly effective, long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) method [Citation1]. Irregular bleeding due to the local effect of levonorgestrel on the endometrium is common [Citation2,Citation3], particularly during the first 3 months of use [Citation4–7]. Many women go on to experience progressively lighter bleeding over 5 years of use [Citation4–7]. Although discontinuation rates due to bleeding changes (including amenorrhoea) are low (∼5%) in clinical trials [Citation4,Citation5,Citation7], lack of awareness of these changes can affect satisfaction and continuation with the method [Citation8–10]. Similarly, changes such as irregular bleeding and amenorrhoea can be unacceptable in some cultures and seen as a barrier to method use [Citation11,Citation12].

The European Thinking About Needs in Contraception (TANCO) study [Citation13] showed that, despite high levels of satisfaction with currently available methods, women are interested in receiving more information about all contraceptive options. Approximately three quarters of women said that they would consider a LARC method if they received more information, an interest that was also clearly shown in the US Contraceptive CHOICE Project [Citation14]. Describing the likelihood and nature of changes in bleeding as part of an effective counselling approach may contribute to addressing women’s information needs regarding LARC methods.

Published data on bleeding patterns with the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS from phase II and III trials have been previously described [Citation4,Citation7], together with advice on counselling women about what to expect in terms of bleeding following placement. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends use of 90-day reference periods, as specified in the Belsey et al. [Citation15] criteria, when reporting bleeding patterns related to hormonal contraceptive use. These longer intervals fail to provide information on bleeding changes immediately after placement, or potential for changes on a month-by-month basis. This retrospective analysis of pooled data from previous randomised controlled studies therefore set out to provide additional description of early bleeding patterns in women using the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS, analysed by 30-day reference periods, for the first year of use. This information should provide relevant and clinically meaningful information for women and health care providers (HCPs) when discussing what to expect in terms of bleeding changes during the first few months of use of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS.

Methods

This retrospective analysis looks at the changes in bleeding patterns with use of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS over 5 years. It includes analysis of bleeding duration and bleeding intensity, based on the proportion of bleeding versus spotting days (see definitions below), following placement of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS. It also includes observations regarding the effect of previous contraceptive method (immediate prior use) and systems with different levonorgestrel doses (13.5 and 52 mg) on bleeding patterns.

The analyses use pooled data from two randomised controlled studies: a phase II, open-label, randomised, dose-finding study involved 741 nulliparous and parous women aged 21–40 years (inclusive); and a phase III study comparing the safety and contraceptive efficacy of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS with that of the 13.5 mg LNG-IUS in 2904 18- to 35-year-old nulliparous or parous women, for a maximum of 3 years (plus an open-label, 2-year study extension to assess the safety and efficacy of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS over 5 years) [Citation4,Citation5,Citation7]. Full details of these studies have been previously described [Citation4,Citation5,Citation7]. All women included in the studies were in good general health and in need of contraception. Bleeding episodes were recorded every day using diary cards provided.

Definitions of bleeding intensity in the retrospective analysis were broadly based on recommendations by the WHO and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) [Citation15,Citation16] and reflected those used in the initial phase II and III studies [Citation4,Citation5,Citation7]. Three different categories of intensity were identified: (1) no bleeding, (2) spotting and (3) bleeding (which included light, normal and heavy bleeding). Spotting was defined as no need for sanitary protection, or panty liner use only; light bleeding was defined as need for sanitary protection but less than associated with normal menstruation in the woman’s experience; normal bleeding was defined as similar to normal menstruation in the woman's experience; heavy bleeding was defined as more than normal menstruation in the woman’s experience.

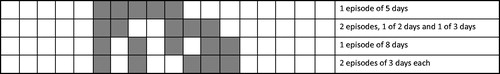

A bleeding episode was defined as day(s) with bleeding and/or spotting of which at least 1 day was of intensity 3 (light, normal or heavy bleeding), preceded and followed by at least 2 bleed-free days () [Citation17]. A week-based approach (where 0.5 weeks = 4 days; 1 week = 7 days etc.) was used to describe the number of bleeding and/or spotting days, as this was seen as more relevant to real-life use by women.

Bleeding patterns were analysed by 30-day reference periods for the first year. Thirty days was chosen as the reference period to provide more detail of the short-term changes in bleeding after LNG-IUS placement. As the definition of amenorrhoea relates only to 90-day reference periods where bleeding and spotting are absent [Citation16], the term is not used in this analysis.

Missing data were handled by looking at the number of missing days per reference period (and whether they were consecutive or non-consecutive) and by incomplete reference periods. In a 30-day reference period, up to 2 missing (non-consecutive) days were replaced in a worst-case approach, i.e., the highest intensity on the days before and after the missing day. If there were >2 consecutive missing days, the entire reference period was excluded for the purpose of analysis. For the 5-year analysis, i.e., 360 day reference periods, up to 20 missing (non-consecutive) days were replaced in a worst-case approach. For incomplete reference periods (i.e., where participants failed to record bleeding data or discontinued LNG-IUS use), any reference period that contained bleeding data for less than two-thirds of the expected length (i.e., <20/30 days or <240/360 days) was omitted from the analysis. Where reference periods were incomplete but contained data for more than two-thirds of the expected length (i.e., ≥20/30 days or ≥240/360 days), the number of bleeding and/or spotting days was extrapolated from the actual number of bleeding and/or spotting days recorded and rounded to the nearest integer.

Bleeding changes with the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS were analysed according to previous contraceptive use (method in use at the screening visit immediately prior to study commencement) and grouped as follows: combined oral contraceptive (COC), combined non-oral contraceptive, intrauterine device (IUD), LNG-IUS, non-hormonal contraceptive, and progestin-only oral contraceptive. Additional analyses compared bleeding patterns by parity, age and different doses of levonorgestrel (13.5 mg LNG-IUS and 52 mg LNG-IUS). All aspects of the bleeding diary analysis were conducted internally by Bayer AG, Berlin, Germany.

Results

Study population

A total of 1697 19.5 mg LNG-IUS users were included in the 12-month pooled analysis of data from the phase II and III studies. The baseline characteristics of the participants are summarised in . Analysis of the 5-year bleeding pattern data comprised 1452 19.5 mg LNG-IUS users who participated in the phase III study and extension phase.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants in the phase II and III studies.

Discontinuation rates due to bleeding problems

In the pooled data from the phase II and III studies, 2.8% (n = 48) of women discontinued use of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS because of bleeding problems (including absence of bleeding) by the end of the first year and 4.5% (n = 76) discontinued by the end of 3 years. Analysis of 5-year data from the phase III extension study showed a discontinuation rate of 5.2% (n = 76) due to bleeding problems.

Impact of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS on bleeding and/or spotting days during the first 12 months

Pooled results from the phase II and III studies (n = 1697) showed that the majority of women experienced a progressive decline in the number of bleeding and/or spotting days and the number of bleeding episodes in the 12 months after placement of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS.

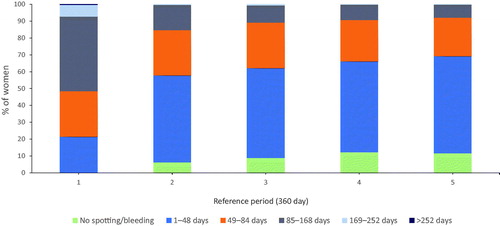

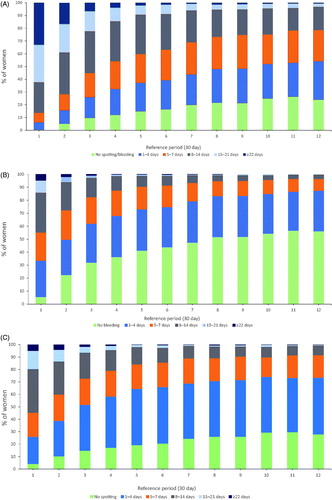

There was an increase in the proportion of women who experienced no bleeding and/or spotting days per month (30 day reference period): from <1% during month 1 to 5.1% in month 2, 9.7% in month 3, 16.0% in month 6 and 24.0% in month 12 (). The proportion of women who experienced a low number of bleeding and/or spotting days (≤4), including those women with 0 days, increased each month from 6.2% in month 1 to 15.8% in month 2, 26.0% in month 3, 39.3% in month 6 and 54.1% in month 12. There was a consistent decline in the proportion of women experiencing prolonged bleeding and/or spotting days (≥8 days per month), from 86.3% in month 1 to 71.5% in month 2, 55.1% in month 3, 36.7% in month 6 and 21.3% in month 12.

Figure 2. Proportion of women experiencing (A) bleeding and/or spotting days per month; (B) bleeding days per month; (C) spotting days per month. (Pooled data, 30-day reference period, n = 1697).

Analysis of bleeding days only () showed that the proportion of women with a low number of bleeding (as opposed to bleeding and/or spotting) days per month increased during the first year after 19.5 mg LNG-IUS placement. The proportion of women who had ≤4 bleeding days (including those women with 0 days) per month increased from 33.6% in month 1 to 49.8% in month 2, 62.0% in month 3, 74.9% in month 6 and 87.4% in month 12. There was a consistent decline in the proportion of women experiencing prolonged bleeding (≥8 days per month), from 44.7% in month 1 to 27.6% in month 2, 17.6% in month 3, 8.6% in month 6 and 3.5% in month 12.

Analysis of spotting days only (i.e., no bleeding recorded) () showed that the proportion of women with ≤4 spotting days per month (including 0 spotting days) increased from 26.0% in month 1 to 39.0% in month 2, 51.8% in month 3, 73.6% in month 6 and 91.6% in month 12.

Impact of previous contraceptive method, age and parity on bleeding patterns with the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS

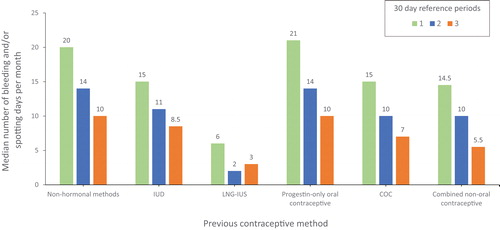

The number of bleeding and/or spotting days per month over the first 3 months recorded in the LNG-IUS phase III study were analysed according to previous contraceptive use (COC, n = 456; combined non-oral contraceptive, n = 88; IUD, n = 59; LNG-IUS, n = 40; non-hormonal contraceptive, n = 767; progestin-only oral contraceptive, n = 36). The number of bleeding and/or spotting days per month declined with use of all methods in months 1 and 2 (). The median number of bleeding and/or spotting days per month was consistently lowest in women who had previously been using an LNG-IUS (median [mean ± standard deviation (SD)] 6 [6.3 ± 4.1], 2 [3.9 ± 4.5] and 3 [3.8 ± 3.5] days in months 1, 2 and 3, respectively), followed by those switching from COCs, combined non-oral contraceptives and the IUD (). Women without prior hormonal contraception and those switching from progestin-only oral contraceptives had considerably more bleeding and/or spotting days in month 1 (median [mean ± SD] 20 [19.3 ± 7.7) and 21 [20.4 ± 6.4] days, respectively). Despite a strong tendency to decline during months 2 and 3, there remained a noticeable difference in the median number of bleeding and/or spotting days experienced by women across the different methods (). The proportion of women with a low number of bleeding and/or spotting days (≤4), including women with 0 days, was greatest where women switched from the LNG-IUS (57.9%), followed by combined non-oral methods (39.3%) and COCs (34.4%) ().

Figure 3. Median number of bleeding and/or spotting days per month (30-day reference period) according to previous contraceptive method (n = 1452).

Table 2. Proportion of participants experiencing bleeding and/or spotting days per month, categorised by previous contraceptive use.

Pooled analysis of changes in bleeding pattern experienced by women of different age groups (18–25 versus 26–35 versus >35 years) showed no relevant differences. In month 1, the mean (SD) number of bleeding and/or spotting days was 18.0 ± 8.3 vs 16.9 ± 7.8 versus 16.3 ± 7.8, respectively; in month 12, the mean number of bleeding and/or spotting days had declined to 4.6 ± 4.5 versus 4.7 ± 4.3 versus 5.0 ± 4.1, respectively (). Analysis of changes in bleeding pattern by parity also showed no relevant differences (data not shown).

Table 3. Median number of bleeding and/or spotting days per month, by age group.

Changes in bleeding days as a proportion of bleeding and/or spotting days per month

Analysis of the proportion of bleeding days in the overall number of bleeding and/or spotting days per month (30-day reference period) showed a trend towards fewer bleeding days and more spotting days over time ().

Table 4. Median percentage of bleeding days within overall number of bleeding and/or spotting days per month.

Impact of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS on bleeding patterns at 5 years

For this analysis, data from the menstrual diaries in the phase III study (n = 1452) describing bleeding and/or spotting days are presented in 360-day reference periods (years) (). The proportion of women who experienced no bleeding and/or spotting days increased from <1% at the end of year 1 to 11.7% at the end of year 5. When looking at women who experienced a low number of bleeding and/or spotting (≤48) days per year, the proportion increased from 21.6% at the end of year 1 to 69.3% of women at the end of year 5.

Impact of levonorgestrel dose on bleeding patterns

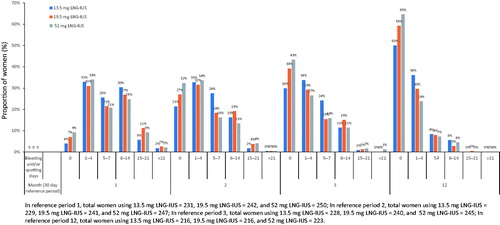

Analysis of bleeding and/or spotting data with the 13.5, 19.5 and 52 mg LNG-IUS in the phase II study showed that there was a steady, dose-dependent increase in the proportion of women with no bleeding and/or spotting days over 12 months (). When looking at the proportion of women with a low number of bleeding and/or spotting days (≤4), including women with 0 days, per month, the differences between the three systems declined over time.

Figure 5. In reference period 1, total women using 13.5 mg LNG-IUS = 231, 19.5 mg LNG-IUS = 242, and 52 mg LNG-IUS = 250; In reference period 2, total women using 13.5 mg LNG-IUS = 229, 19.5 mg LNG-IUS = 241, and 52 mg LNG-IUS = 247; In reference period 3, total women using 13.5 mg LNG-IUS = 228, 19.5 mg LNG-IUS = 240, and 52 mg LNG-IUS = 245; In reference period 12, total women using 13.5 mg LNG-IUS = 216, 19.5 mg LNG-IUS = 216, and 52 mg LNG-IUS = 223.

Patterns after bleeding- and/or spotting-free months

Three months after placement of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS, 68.5% of all women (n = 1697) went on to have at least one bleeding- and/or spotting-free month (30 day reference period) during the following year; 21.2% of women went on to have at least 6 bleeding- and/or spotting-free months. Among the women with no bleeding and/or spotting in month 3 (n = 459), 34.9% reported no further bleeding and/or spotting in the subsequent 9 months. Overall, 72.1% of these women had ≤3 bleeding and/or spotting episodes in the 9-month time frame. Among women with no bleeding and/or spotting episodes in month 6 (n = 617), 49.3% reported no further bleeding and/or spotting in the subsequent 6 months; overall, 86.1% of women had three or fewer bleeding and/or spotting episodes in the 6-month time frame.

Discussion

Main findings

Closer analysis of bleeding diaries using 30-day reference periods provides more detailed insight into bleeding changes in the first months following placement of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS. This descriptive analysis showed that the majority of women experienced a progressive decline in the number of bleeding and/or spotting days and the number of bleeding episodes, beginning after the first month and continuing steadily until 12 months.

Our analysis showed that parity and age did not influence early (within the first 2 months) bleeding changes but that previous contraceptive use was an important factor. Women using combined or progestin-only oral contraceptives experienced the highest initial bleeding followed by the greatest decline in the number of bleeding and/or spotting days during the first 3 months of 19.5 mg LNG-IUS use. The low number of bleeding and/or spotting days generally experienced by women who had previously been using an LNG-IUS continued with the switch to the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS. Although these differences are unlikely to be clinically relevant, they may prove beneficial to women when considering method choice prior to placement. The opportunity to counsel women on the likelihood of specific bleeding changes continuing beyond the first 3–6 months may also be useful when discussing continued use.

The main focus of this analysis was to assess changes in bleeding patterns by 30 day reference periods following placement of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS. Comparison of bleeding changes across three different LNG-IUS doses confirmed a consistent reduction in the number of bleeding and/or spotting days and that this effect was progressive over the lifetime of system use. The magnitude of bleeding reduction appeared, however, to follow a dose response. This information may prove useful when counselling women about the choice of method and the need for an additional benefit of shorter periods of bleeding. The shift away from bleeding days towards more spotting days may be particularly relevant to those women who would like to see a reduction in bleeding but who are not actively seeking amenorrhoea [Citation5].

Relevance of the findings: implications for HCPs?

The European TANCO study [Citation13] reported that almost two-thirds of women regarded reduced bleeding intensity as an important attribute of a contraceptive method. Almost three quarters of HCPs also recognised this as important to women. Studies also show that clear counselling on what bleeding changes may be expected should be an important part of a woman’s decision-making process, and managing expectations may help with method continuation [Citation8–10,Citation18]. Although the possibility of bleeding changes is included in the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS prescribing information [Citation19], this retrospective analysis equips HCPs with further, detailed information they can use when counselling women about what to expect regarding the timing and duration of bleeding changes as well as the impact of the previous contraceptive method. It may also be helpful in managing expectations of those women who experience more prolonged bleeding in the first few weeks and present with concerns about continued use [Citation8,Citation9].

Strengths and limitations

This retrospective analysis of pooled data from two randomised controlled studies provides additional, detailed description of bleeding changes experienced by women using the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS over a 5-year period. Although dropouts were not accounted for in the analysis, the low discontinuation rate (5.2%) due to bleeding problems, including absence of bleeding, in the phase III extension study suggests that the results are unlikely to be affected. The possibility of an effect cannot, however, be excluded entirely.

One of the limitations of this retrospective analysis is the subjectivity of bleeding diaries. Although data gathered via this method have greater sensitivity and specificity than self-reported changes in menstrual flow and frequency, an element of subjectivity remains. In addition, diary use requires intensive application by study participants over an extended period of time. We attempted to minimise the effect of incomplete diary completion by replacing missing data with probable values based on other available information. In this case, we replaced up to two missing (non-consecutive) days with the worst-case scenario, i.e., the highest intensity of those days before and after the missing day. Although there are still limitations with this approach, it enabled the use of standard analytical techniques applicable to a complete dataset.

A further limitation relates to the population characteristics across the two studies. Although the participants had similar characteristics, there were small differences in race and age between the studies. No relevant differences in bleeding patterns following placement of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS were seen across different age groups. The number of women aged >35 years were, however, in the minority and reflected the inclusion criteria of the original phase II and III studies, which were 20–40 years and 18–35 years, respectively [Citation4,Citation7].

The lack of detailed information about bleeding intensity in terms of ‘heavy bleeding’ may be regarded as a limitation of our retrospective analysis of bleeding pattern changes. Although the bleeding definitions used were broadly based on those of the WHO and FIGO [Citation15,Citation16], the main aim of the retrospective analysis was to provide more detailed information about the duration of bleeding and the nature of that bleeding in terms of bleeding and spotting. Self-assessment of heavy bleeding can be subjective [Citation20], by grouping light, normal and heavy bleeding together, a useful picture of episodes that involved bleeding, bleeding and/or spotting and spotting was obtained and, we believe, limited the impact of participants’ subjectivity.

Interpretation

This retrospective analysis of early bleeding pattern data builds on the knowledge provided by previously published data from the phase II and III trials of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS [Citation4,Citation5,Citation7] and shows that women generally experience progressively lighter (i.e., more spotting and less bleeding) and shorter bleeding episodes with use of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS in months 1 and 3. Reported discontinuation rates due to bleeding (4.5% at 3 years and 5.2% at 5 years) reflect those observed in other studies [Citation5,Citation21].

Studies show that bleeding pattern changes impact on LARC continuation [Citation9]. In a cross-sectional survey of teenagers by Schmidt et al. [Citation9], negative bleeding changes, including duration of bleeding, were cited as reasons for discontinuation, and women reported feeling ill-prepared and ill-equipped to handle the changes. The authors found that bleeding changes were also an important influence on the decision to use intrauterine contraception, with young women who were seeking amenorrhoea or fewer days of bleeding choosing the LNG-IUS [Citation9].

The extent to which the information provided by the retrospective analysis of pooled data for the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS is useful to HCPs and women remains to be evaluated. We do, however, know that women are interested in receiving information about LARC methods and that greater provision of information about contraceptive methods can help women make more informed choices [Citation13]. Further insights into the aspects of bleeding that women may find most useful, i.e., in terms of number and duration of bleeding days or episodes or regularity of those episodes and how they would like to access this information, would help to assess the utility of these data. The studies described in this article show that some women continue to experience bleeding problems. Awareness of the importance of clinical assessment for structural pathology or bleeding disorders that may play a role must not be overlooked.

Conclusion

The LNG-IUS is an effective method of contraception, associated with high levels of satisfaction among women of all age groups. Detailed analysis of changes in bleeding patterns in the first 3 months after placement of the 19.5 mg LNG-IUS and insights into the likelihood of continuation in light of both positive and negative changes will prove useful to HCPs when counselling women about method choice and continuation.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was granted for the original phase II and III studies and is recorded in references [Citation7] and [Citation4], respectively.

Acknowledgements

This publication and its content are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Anita Nelson, Oskari Heikinheimo, Dustin Costescu, Agnaldo Lopes Silva Filho and Andrea Lukes, who reviewed the clinical interpretation of the results. Medical writing assistance was provided by Clark Health Communications under the direction of the authors and paid for by Bayer AG.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, et al. Comparative contraceptive effectiveness of levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices: the European Active Surveillance Study for intrauterine devices. Contraception. 2015;91:280–283.

- Suvisaari J, Lahteenmaki P. Detailed analysis of menstrual bleeding patterns after postmenstrual and postabortal insertion of a copper IUD or a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 1996;54:201–208.

- Andersson JK, Rybo G. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device in the treatment of menorrhagia. BJOG. 1990;97:690–694.

- Gemzell-Danielsson K, Apter D, Dermout S. Corrigendum to “Evaluation of a new, low-dose levonorgestrel intrauterine contraceptive system over 5 years of use”. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;233:164–128. Erratum 2019;233:164–165.

- Nelson AL. LNG-IUS 12: a 19.5 levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for prevention of pregnancy for up to five years. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2017;14:1131–1140.

- Jensen J, Mansour D, Lukkari-Lax E, et al. Bleeding patterns with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system when used for heavy menstrual bleeding in women without structural pelvic pathology: a pooled analysis of randomized controlled studies. Contraception. 2013;87:107–112.

- Gemzell-Danielsson K, Schellschmidt I, Apter D. A randomized, phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and Mirena. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:616–622.

- Diedrich JT, Desai S, Zhao Q, et al. Association of short-term bleeding and cramping patterns with long-acting reversible contraceptive method satisfaction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:50.e1–50.

- Schmidt EO, James A, Curran KM, et al. Adolescent experiences with intrauterine devices: a qualitative study. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57:381–386.

- Mansour D. International survey to assess women’s attitudes regarding choice of daily versus nondaily female hormonal contraception. Int J Women's Health. 2014;6:367–375.

- Nappi R, Kaunitz A, Bitzer J. Extended regimen combined oral contraception: a review of evolving concepts and acceptance by women and clinicians. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016;21:106–115.

- Edelman A, Micks E, Gallo MF, et al. Continuous or extended cycle vs. cyclic use of combined hormonal contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;7:CD004695.

- Merki-Feld GS, Caetano C, Porz TC, et al. Are there unmet needs in contraceptive counselling and choice? Findings of the European TANCO study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2018;23:183–193.

- Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, et al. Preventing unintended pregnancy: the contraceptive CHOICE project in review. J Women's Health. 2015;24:349–353.

- Belsey EM, Machin D, d'Arcangues C. The analysis of vaginal bleeding patterns induced by fertility regulating methods. World Health Organization Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction. Contraception. 1986;34:253–260.

- Fraser IS, Critchley HO, Broder M, et al. The FIGO recommendations on terminologies and definitions for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2204–2208.

- Gerlinger C, Endrikat J, Kallischnigg G, et al. Evaluation of menstrual bleeding patterns: a new proposal for a universal guideline based on the analysis of more than 4500 bleeding diaries. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2007;12:203–211.

- Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105–1113.

- Bayer AG. Kyleena (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system). Prescribing Information 2016.

- Fraser IS, Langham S, Uhl-Hochgraeber K. Health-related quality of life and economic burden of abnormal uterine bleeding. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;4:179–189.

- Schreiber CA, Teal SB, Blumenthal PD, et al. Bleeding patterns for the Liletta levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2018;23:116–120.