Abstract

Purpose: Evidence from real-world settings is important to provide an accurate picture of health care delivery. We investigated use of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) in women aged 15–49 years.

Materials and methods: Two surveys, one of women and one of health care professionals (HCPs), were conducted in parallel across seven countries. Participating women completed an online survey to assess contraceptive awareness, current method of contraception, age, and experience with current contraceptive method. HCPs participated in an online survey to provide practice-level information and three anonymous charts of hormonal LARC users.

Results: Of 6903 women who completed the survey, 3225 provided information about their current primary contraception method. Overall, 16% used LARC methods, while 52% used oral contraceptives (OCs). Of hormonal intrauterine system users, 72% described their experience as ‘very favourable’, compared with only 53% of women using OCs. Anonymous patient records (n = 1605) were provided by 550 HCPs who completed the online survey. Most women (64%) had used short-acting reversible contraception before switching to LARC. Physicians perceived 56–84% of LARC users to be highly satisfied with their current form of contraception.

Conclusions: Although usage of LARC was low, most women using LARC were highly satisfied with their method of contraception.

Introduction

Around 40% of all pregnancies worldwide are unintended [Citation1] with potential negative medical and psychological consequences for the mother and the child [Citation2–4]. Unintended pregnancy rates are generally highest among women aged <25 years [Citation5–8] who are more likely to be nulliparous than women aged >35 years [Citation9]. Younger women also more frequently use user-dependent contraception or no contraception [Citation10], despite their higher fecundity [Citation11]. Rates of unintended pregnancy also vary widely between regions/countries, and indeed estimating the true burden and cost unintended pregnancy presents a great challenge due to variability in assessing and reporting these data and the definition of intendedness [Citation12,Citation13].

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods eliminate the need for user adherence [Citation14] and are associated with low rates of unintended pregnancy [Citation15]. Indeed, increased usage of LARC methods has been associated with lower abortion rates in a US study [Citation16]. LARC methods are also associated with high continuation and satisfaction rates, and high cost-effectiveness [Citation14,Citation17]. LARC methods include hormonal (intrauterine system [IUS] and contraceptive implant) and non-hormonal (copper intrauterine device [IUD]) methods, and have efficacy similar to surgical sterilisation [Citation18].

Despite the high efficacy and satisfaction rates associated with LARCs, and in particular with intrauterine contraception (IUC), only around 14% of women of reproductive age worldwide use IUC [Citation19]. This figure varies widely between continents/regions – data from the USA, for example, indicates that despite an increase in uptake between 2008 and 2014 the prevalence of IUC use among nulliparous women aged 15–44 remains low at 4% [Citation20]. In Europe, use of IUC is estimated to be around 17% in women aged 15–49 who use contraception [Citation19]. A woman’s decision to initiate contraception is highly individual and can be influenced by a number of factors. Regarding hormonal contraception, women often have misperceptions and concerns and, in one large survey, fears over long-term effects, the impact on future fertility and reduced libido were reported by over 40% of women [Citation21]. For IUC specifically, fear of insertion pain or concern around having a foreign object inside the body can be important barriers for women [Citation21–23]. In addition, factors such as the increased initial cost of the method and perceived invasiveness of the insertion procedure compared with other methods may also limit the uptake of IUC [Citation24,Citation25].

In recent years, global and national organisations have adapted their recommendations regarding best practice in contraceptive counselling, focusing on broadening access to LARC methods by increasing awareness and removing barriers related to age, parity and safety aspects [Citation14,Citation17,Citation26–31]. In addition, smaller intrauterine contraceptives with a lower hormonal content that may be more suitable for use in nulliparous women have been developed [Citation32–35]. Devices with a low hormone content may be particularly appealing as 49–66% of women in global and European surveys indicated a preference for a low dose of hormones [Citation21,Citation36].

Even with these recommendations and new developments, lack of knowledge of LARCs and misconceptions around safety and side effects continue to limit women’s access to these highly effective methods [Citation19,Citation22,Citation37–39]. Health care professionals (HCPs) are a trusted source of information and play a key role in providing women with information about contraception [Citation40]. However, despite this paradigm shift around the use of LARCs, many HCPs still believe that IUC is unsuitable for young or nulliparous women, and a lack of practical training and experience means that they may not always include IUC in contraceptive counselling [Citation37–40].

Although randomised clinical trials remain the gold standard for evaluating product efficacy under controlled conditions, there are limitations to the types of information they can provide [Citation41]. Evidence, such as that provided by health care surveys, can give a more accurate picture of health care delivery and what individuals think and feel about health care in a real-world setting [Citation42,Citation43]. Analysis of such evidence can also provide information that is impossible or unfeasible to obtain otherwise (e.g., because such studies would be impractical, very expensive or ethically unacceptable) [Citation44]. In this international survey, we investigated the current use of hormonal LARCs in women aged 15–49 years in North America and Europe, and identified the contraceptive methods most used by young women.

Materials and methods

Two surveys, one of women and one of HCPs, were conducted in parallel across seven countries (Germany, France, the UK, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Canada, and the USA) during September and October 2015.

Women were recruited from two large global consumer panels and were asked to participate in a 5-min online survey. Eligible women were aged 15–49 years (Canada, France, Germany, Belgium, Czech Republic) or 18–49 years (USA, UK). Data captured included aided contraceptive awareness, current method of contraception, age, and, if applicable, experience with their current contraceptive method, rated from 1 (not at all favourable) to 7 (extremely favourable).

HCPs were recruited from the Healthcare Advisors Bureau Community Panel which comprises HCPs from around the world. They participated in a 30-min online survey, providing practice-level information and three anonymous patient charts of hormonal LARC users. For patient charts, product quotas were established in order to ensure a robust sample of each LARC product was obtained. HCPs were given feedback regarding quota fulfilment at the time of the survey to ensure only the patient charts required were entered. Eligible HCPs were aged 21–80 years and were specialists in obstetrics/gynaecology, gynaecology or family/general practice, or were nurse practitioners/physician assistants. HCPs were required to have been in practice for 3–40 years, with ≥75% of time spent in direct patient care and ≤50% in a hospital setting, and currently treating or managing at least three women using hormonal LARCs. In the USA, HCPs were required to be board certified or licensed. Chart data included: age, parity, desire for future children, contraceptive use immediately before current LARC method, and HCP perception of satisfaction with LARC method, rated from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 7 (extremely satisfied).

Results

Data from women who completed the online survey

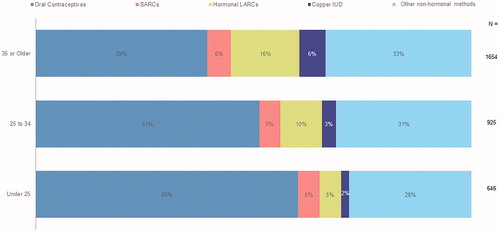

In total, 6903 women completed the women’s survey (). Of these, use of contraception was not appropriate or necessary in 2313 women as they had undergone a sterilisation procedure, were pregnant or trying to get pregnant, were medically infertile or were post-menopausal. Of the remaining women, 3225 provided information about their current primary contraceptive method (); women (n = 1365) who indicated they do not use any contraception or who indicated ‘other’ as a method were excluded from questions about current contraception. Over half of women (52%) used either oral contraceptives (OCs) (47%; mean age, 32.9 years) or other short-acting reversible contraception (SARC) (5%; mean age, 34.8 years). Non-hormonal contraceptives (e.g., condoms, natural methods) were used by 16% of women. LARC users accounted for 16% of women (mean age, 38.5 years; IUS, 10%; copper IUD, 4%; etonogestrel [ENG] implant, 2%).

Figure 1. Primary contraceptive method used by women aged <25 years, 25–34 years and ≥35 years. Oral: combined oral contraceptives and progestogen-only pills; SARCs: vaginal ring, patch, 3-month injectable; hormonal LARCs: LNG 20, LNG-IUS 20, LNG-IUS 8, ENG implants; non-hormonal methods: condoms, spermicide, natural methods. ENG: etonogestrel; IUD: intrauterine device; IUS: intrauterine system; LARC: long-acting reversible contraception; LNG: levonorgestrel; SARC: short-acting reversible contraception.

Table 1. Contraceptive use data collected from women completing the online survey.

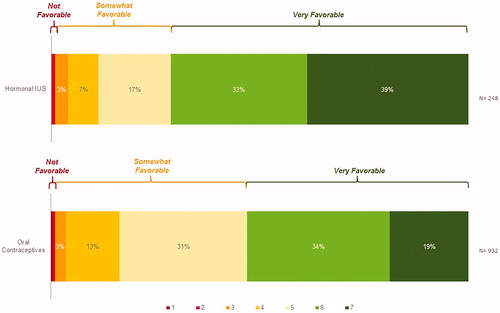

Of women who were current IUS users (n = 307), 81% indicated that they had discussed their current IUS method with others (friends, 65%; family, 54%; co-workers, 27%). A total of 248 women provided information on how favourably they referred to their contraceptive method during those conversations. Overall, 72% of IUS users described their experience as ‘very favourable’, compared with only 53% of women using OCs ().

Figure 2. Favourability of current contraceptive method in women using a hormonal intrauterine system or oral contraceptives*. Favourability rated on a 1–7 scale where ‘1’ is ‘Not at all favourable’ and ‘7’ is ‘Very favourable’. *Subset of women who had previously stated that they had spoken to someone else about IUS (n = 248) or oral contraceptives (n = 932). IUS = LNG-IUS 20, LNG 20 and LNG-IUS 8. IUS: intrauterine system; LNG: levonorgestrel.

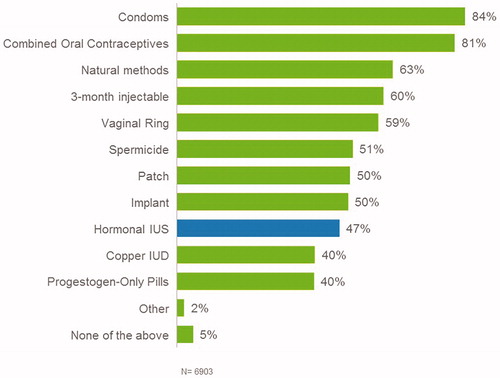

All 6903 women answered questions about their awareness of specified contraceptive methods, the most common methods of which women were aware were condoms (84%), OCs (81%) and natural methods (63%) (). Of other SARC methods, 60%, 59% and 50% of women were aware of the 3-month injectable, vaginal ring and patch, respectively. Regarding LARC methods, 50% of women were aware of ENG implants, 47% were aware of IUS and 40% were aware of copper IUD.

Figure 3. Women’s aided awareness* of contraceptive methods. *Recognition of specific contraceptive methods from a list of possible methods (including examples of country-specific brand names) offered as a prompt. IUS = LNG-IUS 20, LNG 20 and LNG-IUS 8. IUD: intrauterine device; IUS: intrauterine system; LNG: levonorgestrel.

Data from charts provided by HCPs who completed the online survey

In total, 550 HCPs completed the online HCP survey and provided 1605 anonymous records for current hormonal LARC users (). A total of 41% of women in the records provided were current users of either levonorgestrel (LNG)-IUS 20 (Mirena®) or LNG 20 (Liletta®/Levosert®)1, 36% were users of LNG-IUS 8 (Jaydess®/Skyla®), 23% were users of ENG implants. It should be noted that at the time of the survey, LNG-IUS 12 (Kyleena®) was not available in the selected countries, therefore information on users of this method are not included in the results.

Table 2. Long-acting reversible contraceptive use data collected from anonymous records

Immediately before starting their current LARC method, the majority of current LNG-IUS 202 users were either OC users (58%) or other SARC users (6%) (). Seventy-two percent of LNG-IUS 8 users and 75% of ENG implant users were either OC users (65% and 70%, respectively) or other SARC users (7% and 5%, respectively) immediately before starting LARC.

Figure 4. Contraceptive use immediately before current long-acting reversible contraception. ![]()

![Figure 4. Contraceptive use immediately before current long-acting reversible contraception. Display full size Other/don’t know; Display full size No previous hormonal contraception; Display full size No immediately prior contraception (on a break); Display full size Oral (combined oral contraceptive or progesterone-only pill); Display full size Other short-acting reversible contraception (vaginal ring, patch, 3-month injectable); Display full size Long-acting reversible contraception (LNG-IUS, IUD, implant). *Because of the low numbers of users of levonorgestrel (LNG 20; total content 52 mg levonorgestrel [Liletta®/Levosert®]), data were combined with those for the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS 20; total content 52 mg levonorgestrel [Mirena®]). IUD: intrauterine device; IUS: intrauterine system; LNG: levonorgestrel.](/cms/asset/360cff2b-d9b8-4113-a31a-1cbfe7408a15/iejc_a_1666362_f0004_c.jpg)

Users of LNG-IUS 8 (average age, 26.1 years) and ENG implants (26.6 years) were younger than LNG-IUS 20 users (36.2 years). Fifty percent and 4% of LNG-IUS 8 and LNG-IUS-20 users, respectively, were under 25 years, and 12% and 64% were aged 35 years or older. A similar age distribution trend to the LNG-IUS 8 was found with ENG implant users, of whom 47% were younger than 25 years and 17% were aged 35 years or older.

Among current LARC users, 95% of LNG-IUS 20 users had borne at least one child (14%, 54% and 27% having had one, two or three children, respectively). Conversely, over half of LNG-IUS 8 and ENG implant users were nulliparous (62% and 53%, respectively). A greater proportion of LNG-IUS 8 and ENG implant users expressed a desire for future children (72% and 59%, respectively) with a similar proportion being undecided (16% and 21%, respectively) compared with LNG-IUS 20 users.

Physicians answered questions about their perception of women’s satisfaction with hormonal LARCs. Physicians perceived 83% of LNG-IUS 20 users, 75% of LNG-IUS 8 users and 56% of ENG implant users to be highly satisfied (a response of very or extremely satisfied) with their current form of contraception ().

Discussion

Findings, comparison with findings from other studies and interpretation

The most common method of hormonal contraception in women who completed the online survey was the contraceptive pill, and OCs were also the most commonly used ‘immediately prior’ method of contraception indicated by HCPs chart reviews. These findings are in agreement with the US study by Mosher and Jones [Citation10] and with the European TANCO study [Citation36], both of which reported that OCs are the leading method of hormonal contraception as well as the most common method for women starting contraception for the first time. In the present survey, non-hormonal methods (condoms, spermicides, natural methods and copper IUD) were used by approximately 17% of women overall. This is somewhat less than data from a large analysis of US National Surveys of Family Growth which reported 25% of women using non-hormonal methods (not including copper IUD) in 2014 [Citation45].

Importantly, OCs, SARCs and non-hormonal methods are less effective than LARC methods under typical use because of their high dependence on user compliance, which probably contributes to the continuing problem of unintended pregnancy [Citation18,Citation46]. Indeed, recent data from the USA suggest that women seeking contraception, particularly younger women, are increasingly turning to LARC methods, largely as a result of newer, more diversified LARCs becoming available [Citation47]. Furthermore, data from the Contraceptive CHOICE study showed a clear difference in uptake of LARC methods after structured counselling that addressed the safety and efficacy of different methods, and all options were available at no cost [Citation24,Citation48].

In the present survey, most women using LNG-IUS 20 were aged ≥35 years and had previously had children, with no desire for future children; whereas about half of women using LNG-IUS 8 or ENG implants were <25 years of age and most were nulliparous with a desire for future children. In women aged <25 years, just over half chose an IUS, compared with three-quarters of women aged ≥35 years. It is possible that the difference in characteristics between women using the assessed LARC options may reflect the different lengths of time the LNG-IUS 20 and LNG-IUS 8 have been available. Indeed, when the LNG-IUS 20 was first introduced, medical guidelines recommended that IUC was prescribed only for women who had completed their families, with the result that it was used primarily by older women. LNG-IUS 20 is also indicated for the treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding) [Citation49] which may occur more frequently in peri-menopausal women possibly contributing to higher use in this age group.

Women’s satisfaction with IUS in the present survey was high, with over 70% describing their method of contraception as ‘very favourable’ to friends, family, or co-workers. In contrast, only 53% of women described their experience with OCs as ‘very favourable’. This experience sharing among peers is of importance because the description of negative experiences or side effects with hormonal contraception by friends and family can subsequently influence a woman’s choice of contraceptive method [Citation50,Citation51].

HCPs’ perceived satisfaction for women using hormonal LARCs was in agreement with women’s reported satisfaction – 83%, 75% and 56% of LNG-IUS 20, LNG-IUS 8 and ENG implant users, respectively, were perceived as ‘highly satisfied’ by HCPs. The LNG-IUS 20 was associated with the highest HCP-perceived user satisfaction. Unlike LNG-IUS 8 and ENG implants, LNG-IUS 20 is licensed for the treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding) [Citation49,Citation52]. The bleeding-related benefits associated with LNG-IUS 20 therefore might have contributed to the perception of higher patient satisfaction among HCPs, who regard the reduction of bleeding intensity and pain during a period as attributes that are important to women [Citation36]. Additionally, HCP-perceived satisfaction of women using an LNG-IUS was higher than for women using ENG implants, this is consistent with a recent study in which the ENG implant was associated with a significantly higher 12-month discontinuation rate than LNG-IUS 8, mainly because of the bleeding profile associated with ENG implants [Citation53].

LARC methods are highly effective contraceptives [Citation15], recommended by international guidelines [Citation14,Citation27,Citation31] and, in the present survey and others [Citation36,Citation54] are considered very favourably by women using them. However, the use of LARC methods is low, possibly as a result of misconceptions among women choosing contraception [Citation22,Citation25]. For hormonal IUC, concerns regarding hormonal side effects are important to women, and fears of infertility, excessive bleeding, weight gain, long-term impacts and reduced sex drive are key issues [Citation21,Citation50,Citation55]. Indeed, in recent years, there has been an increasing amount of interest by women in contraception with a low dose of hormones, possibly as a result of these concerns [Citation21,Citation36,Citation56]. A variety of LARCs are available that can be suited women’s needs and preferences, such as newer IUS containing low doses of hormones. However, some women may not be offered these options as HCPs might underestimate their patients’ interest in this form of contraception [Citation36]. It is important that HCPs provide individualised contraceptive counselling and ensure women are aware of all their options to help them chose the method that is right for them.

Strengths and weaknesses

The large, multinational nature of the reported women’s survey is an important strength, but there are some limitations that should be considered. As an online survey, it may have had limited reach in populations less likely to have internet access or respond to online questionnaires. The potential impact of this is that the information collected may represent a subset of individuals who access the internet and are already interested in the topic and interested in participating in surveys. This may mean that the opinions of other individuals who do not share these characteristics are missed and results may not therefore be generalisable to all women.

The survey applied a programming logic to ensure that inappropriate questions were not asked to participants (e.g., questions about contraception were not asked to women who indicated they were medically infertile), therefore for some questions, sample size is limited which could potentially impact the generalisability of observed findings. Additionally, social demographic data, such as education level or income, that may have an influence on women’s knowledge and awareness of contraceptive methods were not collected. It is also difficult to correlate self-reported knowledge of contraceptive methods with actual knowledge using an online survey. Furthermore, the evaluation of satisfaction did not allow identification of the specific features of contraceptives that may have caused dissatisfaction. Finally, it should be noted that women aged 15–18 years were excluded from the survey in some countries because of the need to obtain parental consent prior to participation, limiting the collection of data from adolescents.

For the HCP survey, anonymous patient charts for copper IUD were not collected. Due to the need to keep the time burden of the survey within reasonable limits, it was determined that a maximum of three charts should be requested from HCPs with a focus on hormonal LARC methods.

Implications

Young women, who are among those at highest risk for unintended pregnancy, still chose OCs as their method of contraception despite the potential lower efficacy if not taken correctly and consistently. Of the women using hormonal LARCs, including women aged <25 years, the majority (72%) were highly satisfied with this effective method of contraception. Users of LNG-IUS 8 and ENG implants tended to be younger than women using LNG-IUS 20. Increasing awareness and removal of barriers to LARC uptake, together with the introduction of newer LARC options with attributes preferable for younger women, is needed to help reduce the burden of unintended pregnancy. Increasing women’s knowledge is also important as a number of misperceptions still surround these effective methods. HCPs have an important role to play in the education and counselling of women regarding contraceptive choices, including LARCs.

Conclusions

This international survey gathered information from women about their knowledge, awareness and attitudes towards contraception. HCPs were surveyed in parallel regarding prescribing practice and perceptions of satisfaction with LARC methods. Hormonal LARCs were associated with high levels of HCP perceived satisfaction and women themselves describe them favourably in conversations with family, friends and colleagues. Despite high levels of satisfaction with hormonal LARCs however, the awareness and usage of these methods were generally low in the surveyed population of women, in line with findings from other studies. Women’s preference for LARCs in the present survey varied widely. Preferences regarding contraceptive method are likely to be influenced by social and economic aspects which may differ by country [Citation21,Citation24,Citation50]. Barriers to IUC use often focus around knowledge and awareness, as well as financial and procedural barriers in some countries [Citation21,Citation24]. Further large-scale surveys would be useful to assess beliefs and knowledge in greater depth as well as investigate reasons for satisfaction with different contraceptive methods. Future research could also attempt to establish the potential country-specific social and economic factors that impact on HCP’s and women’s perceptions of LARCs to further increase our understanding and allow tailoring of educational and awareness-raising efforts. Assessment of the impact of education and initiatives to raise awareness and access to LARCs should also be considered.

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to acknowledge Highfield, Oxford, UK for providing medical writing assistance with funding from Bayer AG.

Disclosure statement

Kai J. Buhling has received speakers’ bureau honoraria from Bayer HealthCare, MSD, Dr. Kade Pharma, Gedeon Richter Co. and AdPharm.

John Crocker is an employee of BluePrint Research Group.

Thomas Faustmann, Carsten Moeller, Cecilia Caetano and Yvonne Engler are employees of Bayer AG.

Notes

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Because of the low numbers of users of levonorgestrel (LNG 20; total content 52 mg levonorgestrel [Liletta®/Levosert®]), data were combined with those for the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS 20; total content 52 mg levonorgestrel [Mirena®]).

2 See Note 1.

References

- Sedgh G, Singh S, Hussain R. Intended and unintended pregnancies worldwide in 2012 and recent trends. Stud Fam Plann. 2014;45:301–314.

- Cheng D, Schwarz EB, Douglas E, et al. Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors. Contraception. 2009;79:194–198.

- World Health Organisation. Safe and unsafe induced abortion. Global and regional levels in 2008, and trends during 1995–2008. WHO/RHR/12.02. 2012; [cited 2019 Feb 19]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75174/1/WHO_RHR_12.02_eng.pdf

- McCrory C, McNally S. The effect of pregnancy intention on maternal prenatal behaviours and parent and child health: results of an Irish cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27:208–215.

- Wellings K, Jones KG, Mercer CH. The prevalence of unplanned pregnancy and associated factors in Britain: findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Lancet. 2013;382:1807–1816.

- Helfferich C, Hessling A, Klindworth H, et al. Unintended pregnancy in the life-course perspective. Adv Life Course Res. 2014;21:74–86.

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:843–852.

- Zolna M, Lindberg L. Unintended pregnancy: incidence and outcomes among young adult unmarried women in the United States, 2001 and 2008. Guttmacher Institute. 2012; [cited 2019 Feb 19]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/unintended-pregnancy-us-2001-2008.pdf

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. SF2.3: Age of mothers at childbirth and age-specific fertility. SF2.3. 2016; [cited 2018 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/SF_2_3_Age_mothers_childbirth.pdf

- Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. Vital Health Stat 23. 2010;29:1–44.

- Menken J, Trussell J, Larsen U. Age and infertility. Science. 1986;233:1389–1394.

- Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Alkema L, et al. Global, regional, and subregional trends in unintended pregnancy and its outcomes from 1990 to 2014: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e380–e389.

- Logan C, Holcombe E, Manlove J, et al. The consequences of unintended childbearing: a white paper. Washington, DC: Child Trends and National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, Vol. 28; 2007; pp. 142–151.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group. Committee Opinion No. 642: increasing access to contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices to reduce unintended pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e44–e48.

- Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1998–2007.

- Peipert JF, Madden T, Allsworth JE, et al. Preventing unintended pregnancies by providing no-cost contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1291–1297.

- Black A, Guilbert E, Co A, et al. Canadian Contraception Consensus (Part 1 of 4). J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37:936–942.

- Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83:397–404.

- Buhling KJ, Klovekorn L, Daniels B, et al. Contraceptive counselling and self-prescription of contraceptives of German gynaecologists: results of a nationwide survey. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2014;19:448–456.

- Ihongbe TO, Masho SW. Changes in the use of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods among U.S. nulliparous women: results from the 2006–2010, 2011–2013, and 2013–2015 National Survey of Family Growth. J Womens Health. 2018;27:245–252.

- Mansour D. International survey to assess women’s attitudes regarding choice of daily versus nondaily female hormonal contraception. Int J Womens Health 2014;6:367–375.

- Hladky KJ, Allsworth JE, Madden T, et al. Women’s knowledge about intrauterine contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:48–54.

- Potter J, Rubin SE, Sherman P. Fear of intrauterine contraception among adolescents in New York City. Contraception. 2014;89:446–450.

- Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, et al. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:115.e1–115.e7.

- Joshi R, Khadilkar S, Patel M. Global trends in use of long-acting reversible and permanent methods of contraception: seeking a balance. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131:S60–S63.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice; Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 450: increasing use of contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices to reduce unintended pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1424–1428.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Long-acting reversible contraception. Clinical Guideline CG30. 2014; [cited 2019 Feb 19]. Available from:https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg30/resources/longacting-reversible-contraception-pdf-975379839685

- Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Intrauterine Contraception, 2015; [cited 2019 Feb 19]. Available from: http://www.fsrh.org/pdfs/CEUGuidanceIntrauterineContraception.pdf

- World Health Organization. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. 5th ed. Geneva: WHO; 2015.

- Black A, Guilbert E, Costescu D, et al. Canadian contraception consensus (part 3 of 4): Chapter 7 – intrauterine contraception. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38:182–222.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence. Contraception for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e1244–e1256.

- Benacerraf BR, Shipp TD, Lyons JG, et al. Width of the normal uterine cavity in premenopausal women and effect of parity. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:305–310.

- Shipp TD, Bromley B, Benacerraf BR. The width of the uterine cavity is narrower in patients with an embedded intrauterine device (IUD) compared to a normally positioned IUD. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:1453–1456.

- Gemzell-Danielsson K, Schellschmidt I, Apter D. A randomized, phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and Mirena. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:616–622.

- Bayer Healthcare. Jaydess. Summary of product characteristics. 2017. [cited 2019 Feb 19]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5297

- Merki-Feld GS, Caetano C, Porz TC, et al. Are there unmet needs in contraceptive counselling and choice? Findings of the European TANCO study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2018;23:183–193.

- Madden T, Allsworth JE, Hladky KJ, et al. Intrauterine contraception in Saint Louis: a survey of obstetrician and gynecologists’ knowledge and attitudes. Contraception. 2010;81:112–116.

- Rubin SE, Fletcher J, Stein T, et al. Underuse of the IUD in contraceptive care and training. Fam Med. 2010;42:387–388.

- Black KI, Lotke P, Lira J, et al. Global survey of healthcare practitioners’ beliefs and practices around intrauterine contraceptive method use in nulliparous women. Contraception. 2013;88:650–656.

- Spiedel J, Harper CC, Shiedls WC. The potential of long-acting reversible contraception to decrease unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2008;78:197–200.

- Garrison LP, Jr., Neumann PJ, Erickson P, et al. Using real-world data for coverage and payment decisions: the ISPOR Real-World Data Task Force report. Value Health. 2007;10:326–335.

- ABPI. The vision for real world data – harnessing the opportunities in the UK. 2011; [cited 2018 Jun 18]. Available from: http://www.abpi.org.uk/media/1378/vision-for-real-world-data.pdf

- Berger ML, Sox H, Willke RJ, et al. Good practices for real-world data studies of treatment and/or comparative effectiveness: recommendations from the Joint ISPOR-ISPE Special Task Force on Real-World Evidence in Health Care Decision Making. Value Health. 2017;20:1003–1008.

- Heikinheimo O, Bitzer J, García Rodríguez L. Real-world research and the role of observational data in the field of gynaecology – a practical review. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2017;22:250–259.

- Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J. Contraceptive method use in the United States: trends and characteristics between 2008, 2012 and 2014. Contraception. 2018;97:14–21.

- Trussell J, Henry N, Hassan F, et al. Burden of unintended pregnancy in the United States: potential savings with increased use of long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2013;87:154–161.

- Law A, Pilon D, Lynen R, et al. Retrospective analysis of the impact of increasing access to long acting reversible contraceptives in a commercially insured population. Reprod Health. 2016;13:96.

- Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105–1113.

- Bayer Healthcare. Mirena. Summary of product characteristics. 2018. [cited 2019 Feb 19]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1132

- Chebet JJ, McMahon SA, Greenspan JA. Every method seems to have its problems – perspectives on side effects of hormonal contraceptives in Morogoro Region, Tanzania. BMC Women’s Health. 2015;15:97.

- Asker C, Stokes-Lampard H, Bevan J, et al. What is it about intrauterine devices that women find unacceptable? Factors that make women non-users: a qualitative study. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2006;32:89–94.

- Gedeon Richter (UK) Ltd. Levosert. Summary of product characteristics. 2019. [cited 2019 Feb 19]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/30120

- Apter D, Briggs P, Tuppurainen M, et al. A 12-month multicenter, randomized study comparing the levonorgestrel intrauterine system with the etonogestrel subdermal implant. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:151–157.

- Borgatta L, Buhling KJ, Rybowski S, et al. A multicentre, open-label, randomised phase III study comparing a new levonorgestrel intrauterine contraceptive system (LNG-IUS 8) with combined oral contraception in young women of reproductive age. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016;21:372–379.

- Podolskyi V, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Marions L. Contraceptive experience and perception, a survey among Ukrainian women. BMC Women’s Health. 2018;18:159.

- Hellstrom A, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Kopp Kallner H. Trends in use and attitudes towards contraception in Sweden: results of a nationwide survey. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2010;24:154–160.