Abstract

Objectives: Because medical, midwifery and law students in Ghana constitute the next generation of health care and legal practitioners, this study aimed to evaluate their attitudes towards abortion and their perceptions of the decision-making capacity of pregnant adolescents.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional survey among 340 medical, midwifery and law students. A pretested and validated questionnaire was used to collect relevant data on respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics, attitudes towards abortion and the perceived capacity and rationality of pregnant adolescents’ decisions. The χ2 test of independency and Fischer’s exact test were used where appropriate.

Results: We retained 331 completed questionnaires for analysis. Respondents’ mean age was 21.0 ± 2.9 years and the majority (95.5%) were of the Christian faith. Women made up 77.9% (n = 258) of the sample. Most students (70.1%) were strongly in favour of abortion if it was for health reasons. More than three-quarters (78.0%) of the students strongly disagreed on the use of abortion for the purposes of sex selection. Most respondents (89.0%) were not in favour of legislation to make abortion available on request for pregnant adolescents, with medical students expressing a more negative attitude compared with law and midwifery students (p < 0.001). Over half of the midwifery students (52.6%) believed that adolescents should have full decision-making capacity regarding their pregnancy outcome, compared with law and medical students (p < 0.001).

Conclusion: Tensions between adolescent reproductive autonomy, the accepted culture of third party involvement (parents and partners), and the current abortion law may require keen reflection if an improvement in access to safe abortion services is envisioned.

摘要

目的:由于加纳的医学、助产学和法学的学生构成下一代保健和法律从业人员, 所以本研究旨在评估他们对堕胎的态度和他们对怀孕少女决策能力的看法。

方法:我们对340名医学、助产学和法学的学生进行了一项横断面调查。采用经预测试和经验证的问卷, 收集了关于受访者的社会人口学特征、对堕胎的态度以及对怀孕少女决策的感知能力及合理性的相关数据。恰当地使用卡方独立性检验和Fischer精确检验。

结果:我们获取了331份完整问卷进行分析。受试者的平均年龄为21.0 ± 2.9岁, 大多数(95.5%)为基督教。样本中77.9%(n=258)为女性。如果是出于健康原因, 大多数学生(70.1%)强烈支持堕胎。超过四分之三(78%)的学生强烈反对出于性别选择的原因进行堕胎。大多数受试者(89.0%)不支持立法规定怀孕少女可要求堕胎, 与助产学和法学学生相比, 医学生的反对态度更多(p<0.001)。与法学生和医学生相比, 半数以上助产学学生(52.6%)认为少女对于其妊娠结局应该有完全的决策能力。

结论:少女生育自主权, 被认可的第三方参与(父母和伴侣)的文化和当前的堕胎法之间的冲突或许要求慎重考虑提升安全堕胎服务的可及性。

Introduction

Unintended pregnancies remain a serious global health concern and are characterised by adverse health, economic and social consequences [Citation1]. Approximately 44% of pregnancies recorded globally between 2010 and 2014 were unintended [Citation2]. Compared with adults, adolescents have higher rates of unintended pregnancies and face more adverse birth- and abortion-related complications [Citation3,Citation4]. Despite a reported increase in the uptake of modern methods of contraception, unintended pregnancies remain a persistent public health challenge. In adolescents specifically, the majority of pregnancies are considered unintended, half of which end in abortion [Citation5,Citation6]. In a hospital-based study in Ghana, Eliason et al. [Citation7] reported an unintended pregnancy rate of 70%, and 90% of adolescent pregnancies sampled were unintended.

The options generally available with an unintended pregnancy are to terminate the pregnancy, continue the pregnancy to term and raise the child, or give the child up for adoption after birth. The decision-making capacity of adolescents to make these decisions is an issue of controversy. In Ghana, no guidelines are available to guide unintended pregnancy (abortion) decision-making, especially among adolescents. Family and partners have been reported to influence pregnancy decisions to some extent. Henshaw and Kost [Citation8] reported a desire by minors who had previously experienced family violence to maintain a healthy relationship with parents as a key determinant of not involving parents in the decision-making process with regard to abortion. Schwandt et al. [Citation9] reported male involvement in decisions about unintended pregnancies in Ghana through ‘orders’ (coercion) and highlighted the role of sex inequality. The final decision to terminate the pregnancy, or keep it, depends mainly on the ‘order’ given by men. Bankole et al. [Citation10] highlighted how family relationships and male denial of responsibility for a pregnancy influenced decision-making in unintended pregnancies. In Ghana, contrary to the general situation in low- and medium-income countries, women were described as being sufficiently autonomous in deciding whether to proceed with a pregnancy [Citation11]. In Ghana, attitudes of health-care providers towards abortion have been reported to influence access to safe abortion services [Citation9,Citation11]. For instance, Schwandt et al. [Citation9] reported how the harsh attitudes of nurses towards clients seeking abortion services negatively affected the quality of safe abortion care and deterred some from seeking and receiving the care they wanted. Oppong-Darko et al. [Citation12] highlighted how the religious convictions of Ghanaian midwives impeded some providers from supplying abortion services. In a qualitative study involving 43 health-care providers across different levels of management (managers, obstetricians, midwives) in three hospitals in Accra, religious views were identified as key potential barriers in the provision of safe abortion care. Midwives, for instance, were most likely to condemn abortions as sinful [Citation13].

We hypothesised that the perceptions of future health-care workers could be eventually translated into their future practice. Considering that medical, midwifery and law students constitute the next generation of health-care and legal practitioners, understanding their attitudes towards abortion and their views regarding adolescent decision-making in pregnancy is crucial, especially with regard to organising the content of their reproductive health training curricula.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted over a 2-month period (November to December 2017) among medical, midwifery and law students at the University of Ghana, School of Medicine and Dentistry (second- and third-year students); the Nursing and Midwifery Training College in Korle-Bu (third-year students); and the School of Law, University of Ghana, Legon campus (second- and third-year students). The questionnaire was first pretested among 10 midwifery and five law students from the target schools. The questionnaire comprised four main sections: sociodemographic characteristics; questions related to perceived capacity and rationality of adolescent decision-making; third party involvement in decision-making; and respondents’ attitudes to induced abortion. Most survey items were reported on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The questionnaire also contained four open-ended questions on adolescents’ decision-making capacity, the specific nature of decision-making in unintended pregnancies, and recommendations on addressing the high rates of unintended adolescent pregnancies. Females aged 19 years or younger were considered as adolescents.

We aimed for a convenience sample of 360 respondents [Citation14]. After an explanation of the study objectives, 360 questionnaires were distributed to students who consented to participate in the study: 60 questionnaires each to second- and third-year medical students (120 in total), 120 to third-year midwifery students, and 60 each to second- and third-year law students (120 in total). Questionnaires were self-administered and completed under the supervision of trained research assistants, each taking about 25–50 min, in lecture halls in the respective institutions. Data from the completed questionnaires were then entered into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets for cleaning, after which data were imported into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software program, version 21.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), for analysis. Multiple imputation was used to manage missing data.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents were summarised using descriptive statistics presented as frequencies and means. Likert scale responses were eventually transformed into two categories: ‘no’ (representing the subgroups strongly disagree, disagree and neutral) and ‘yes’ (representing those who either agreed or strongly agreed to a specific statement). Medians and modes were used as measures of central tendency in analysing Likert scale data [Citation14,Citation15]. The χ2 test of independency and Fischer’s exact test were used to measure associations between dependent variables (attitudes towards abortion and decision-making preferences) and selected independent variables of interest (academic background and sex). Statistical significance was set at a p < 0.05.

Ethics approval

Scientific clearance was obtained from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (WC2017-025) and ethical approval from the Ghana Health Service Ethics Review Committee (003/07/17). Administrative authorisations were obtained from the respective heads of the various universities. Signed informed consent was obtained from all respondents.

Results

Of the 360 questionnaires distributed, 340 were completed (a response rate of 94.4%). Of these, nine were rejected because of incomplete data and 331 were retained for analysis (117 medical students, 114 midwifery students and 100 law students). Respondents’ mean age was 21.0 ± 2.9 years, 95.5% were Christians and 77.9% (n = 258) were women.

Attitudes towards abortion

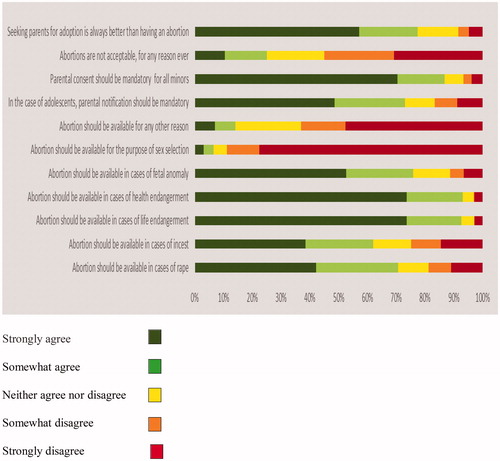

As shown in , most of the students (72.0%) were strongly in favour of making abortion available in situations where the health of the woman was in danger. Most respondents (70.0%) also strongly felt that parental consent should be secured in cases of minors seeking abortion, while a majority (75.0%) preferred adoption over abortion. Not many respondents were strongly in favour of abortion in cases of pregnancies resulting from rape and incest (40.8% and 37.2%, respectively). Compared with law and medical students, midwifery students had a more positive attitude towards abortion in cases of rape and incest. summarises the students’ attitudes towards abortion, by academic discipline. Unsurprisingly, a high proportion of respondents were strongly against the use of abortion services for sex selection (78.0%). Echoing the predominant preference for parental involvement in decision-making for adolescent pregnancies, most students (73.0%) felt health-care staff should notify parents whenever pregnant adolescents sought abortion services. Respondents agreed that abortion should be allowed in cases of incest (62.0%) and foetal malformation (78.0%). A large majority of respondents (89.0%) were not in favour of legislation that made abortion available on request to adolescents. Compared with midwifery (57.9%) and law students (69.1%), medical students (82.6%) expressed views that were more negative.

Table 1. Attitudes towards abortion in pregnant adolescents, by academic discipline.

To ascertain additional strength of conviction with regard to specific questions assessing respondents’ attitudes, we examined the ‘strongly agree’ responses and how they were related to gender and academic discipline (). The table captures responses from 73 male and 258 female students, distributed by academic discipline into medicine (n = 117), midwifery (n = 114) and law (n = 100). Being a midwifery student and being female were associated with a greater likelihood of strongly agreeing that abortion was acceptable in cases of rape, incest and foetal anomaly (p = 0.001). Regarding mandatory notification of parents by health-care providers, midwifery students were more favourable towards this practice, with 77.2% strongly agreeing, compared with 69.2% among medical students and 55.0% among law students (p = 0.002). Attitudes towards sex selection were not associated with academic background nor with sex (p = 0.14, p = 0.34, respectively).

Table 2. Relationships between sex and academic discipline of respondents to their attitudes towards abortion.

Regarding the occurrence of abortion in their respective communities, 19.7% of respondents strongly agreed that abortion was common and 28.4% strongly agreed that unintended pregnancy was very common in their communities. Up to 68.6% of respondents were strongly against the government paying for safe abortion services.

Decision-making capacity of adolescents

Over 47% of respondents believed that an adolescent could only make reasonable decisions from the age of 18 (mean reported maturity attainment age was 17.6 years). Overall, 64.7% (n = 211) of respondents thought that a female adolescent was not mature enough to make her own decision on her pregnancy, while 54.3% (n = 176) felt the adolescent should have the final say. When asked about the most preferred person to be involved in deciding the outcome of an unintended adolescent pregnancy, 46.2% (n = 153) suggested the mother, 24.8% (n = 82) a health-care worker and 16.0% (n = 53) the partner. More than half of the respondents felt that decision-making in unintended pregnancies was different from that of other medical issues. Answers to open-ended questions revealed that the uniqueness of the decision in the case of an unintended pregnancy was that more than one person was involved or affected (partner, unborn child, parents) by the consequences of the decision, thereby making it more sensitive.

Over half of the midwifery students (52.6%) agreed that adolescents had full decision-making capacity regarding their pregnancy outcome, compared with 23.7% of medical students and 28.6% of law students (p < 0.001). Correspondingly, fewer medical (38.9%) and law students (43.3%) would systematically involve a third party in the decision-making process, compared with midwifery (63.2%) students (p = 0.001) ().

Table 3. Perceived decision-making capacity of adolescents, by academic discipline.

Additional findings

Responses to the open-ended questions shed more light on why respondents held certain views on abortion and decision-making in adolescent pregnancies. Those who felt the adolescent should have independent decision-making freedom justified their position by the belief that the adolescent was ultimately responsible for her actions and consequences and that she was mature enough. Others who supported third party influence in the decision-making process were of the opinion that independent decision-making by a pregnant adolescent would lead to irrational decisions and could be influenced by fear or by the attitude of peers. Additional reasons given included possible future regret and inability to bear the consequences of such a decision alone.

We sought to understand respondents’ views on factors that predisposed adolescents to pregnancy. The main reasons cited were individual (i.e., ignorance, poor sexual education and reluctance to discuss sex, peer pressure and curiosity, alcohol and drug abuse), sociocultural (i.e., poor parenting, children from single-parent households, social media, access to pornography) and economic (i.e., high unemployment and school dropout rates, poverty). With respect to how the current high rate of unintended adolescent pregnancy could be reduced, many respondents were of the view that the current comprehensive sexuality education package needed to be improved. Greater engagement of other social actors including religious bodies and the government was also identified as a necessary action point to help curb adolescent pregnancies.

Discussion

Findings and interpretation

The main aim of this study was to assess the attitudes towards abortion of a sample of future health and legal professionals in Ghana, as well as their perceptions of the decision-making capacities of pregnant adolescents. We found that students generally held positive views towards abortion, especially on the grounds of preserving the woman’s health (a view held mostly by students in the health-care domains of medicine and midwifery). Although their health-related academic disciplines could partly explain the high acceptance rate, we found a similarly high acceptance rate among law students as well.

Differences and similarities in relation to other studies

Abortions were considered acceptable in situations where the health or life of the woman was in danger, and in cases of rape, incest and foetal anomaly. These all fall within the purview of the Ghanaian abortion law of 1985, which permits abortion in cases of rape, incest or forced sexual intercourse with a mentally deranged person (‘defilement of a female idiot’), if the life or health of the woman is endangered, or if there is a risk of foetal abnormality [Citation16]. Midwifery students and female students had more positive attitudes towards abortion. Female respondents constituted 77.9% of our study population, and women are probably better placed to identify with the feeling of being pregnant and a desire to be in charge of their lives. As midwifery students included in the study were in their third year, they were more likely to have seen adolescents suffer or die from the complications of unsafe abortion. In a survey among Ghanaian students at the University of Cape Coast, respondents who knew someone with a history of pregnancy termination had a more liberal attitude towards abortion [Citation17]. In their clinical practice, Ghanaian doctors have been reported to have more positive and liberal attitudes towards safe abortion services, compared with nurses [Citation18,Citation19]. Knowledge regarding abortion law and religious convictions has also been reported to play a significant role in Ghana in the willingness to provide safe abortion care [Citation12,Citation16,Citation19]. In northern Ghana, for instance, a high prevalence of conscientious objection to provide abortion services by health-care providers has been reported [Citation19]. Most of the reasons advanced are mainly moral and religious. Unfortunately, the current Ghanaian abortion law does not provide any legal guidelines to deal with conscientious objection [Citation16,Citation19].

Relevance of the findings: implications for clinicians and policy-makers/health-care providers

Despite the positive attitudes of most respondents, the involvement of parents and other third parties including partners, as well as systematic notification by health-care providers to parents of pregnant adolescents, was a strongly held opinion. In the case of third party influence, evidence shows that the cultural preferences and beliefs of the third party, the nature of the relationship with the pregnant adolescent, as well as the quality of information given, can influence the adolescent to keep the pregnancy to term or opt for an abortion [Citation20–23]. Nevertheless, it is important that adolescents have the right environment and adequate resources to make informed decisions. This could be achieved by improving the comprehensive sexuality education packages in schools in a way that is culturally sensitive and specific to the context. Furthermore, health professionals need to be trained prior to their recruitment to provide respectful and non-directive adolescent health-care services. Given the importance of family and community in the Ghanaian setting, the role of the family will also need to be carefully considered in designing safe care packages for abortion and in supporting adolescents in their decision-making process.

Less than one-third of our respondents were in favour of legislation allowing the provision of legal abortion on request by adolescents. In a survey among 1038 students at the University of Cape Coast, Ghana, Rominski et al. [Citation17] reported generally negative views towards abortion being a woman’s right. In a South African social attitudes survey, despite the legalisation in 1996 of abortions on request, over 20% of medical students opined that abortions were always wrong, even in cases of foetal anomaly and extreme poverty [Citation24]. These findings are an indirect indication of how challenging it may be to change the cultural or social perceptions of the population towards abortion despite legal instruments and liberties in place. With over a quarter of respondents in our study also not in favour of government-funded abortion services or making abortion on request legally permissible, there was an indication that abortion seeking among adolescents was socially unacceptable. In our study, over half of our respondents made a distinction between abortion decision-making and decision-making for another medical condition or procedure. It has been argued elsewhere that decision-making in adolescents might differ from that of adults in two main ways: adolescents had less decision-making experience; and decisions taken under emotionally charged circumstances were more likely to be irrational [Citation25]. Over 80% of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that adoption was always a better option than abortion. However, this view might not actually reflect reality. For example, in Nigeria only 42.6% of women suffering from intractable infertility were willing to adopt a child [Citation26].

Strengths and weaknesses

Our study had a number of limitations. First, most of the respondents were female, and our findings are not necessarily representative of the opinions of the general student community in Ghana. Studies involving the broader student community in other regions of the country are required to provide authoritative conclusions regarding overall student attitudes towards abortion. Secondly, we recorded many missing responses. Most of the missing responses in the survey were from law students. The topic area being more familiar to students from the health sciences background could explain this discrepancy. Nonetheless, our findings are of relevance in designing targeted qualitative studies to better ascertain the deeper meanings and implications of these preliminary findings.

Conclusion

Students’ attitudes towards abortion were generally positive, especially when the health of the mother was at stake. Midwifery students portrayed more positive attitudes compared with law and medical students. Studies among practising midwives, nurses and doctors may be helpful to better tailor support and training regarding the provision of respectful, safe abortion services. The overwhelming recommendation for health-care staff to systematically notify the parents of adolescents seeking abortion care could be an impediment for adolescents to access safe abortion services. Most adolescent pregnancies are unintended and generally end in abortion. Despite the absence of existing laws specific to legal abortion service provision for adolescents in Ghana, policy-makers and researchers need to reflect upon improving access to safe abortion services among adolescents.

Acknowledgement

We thank Abejirinde O. Ibukun for her in-depth review of the final draft of this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Alkema L, et al. Global, regional, and subregional trends in unintended pregnancy and its outcomes from 1990 to 2014: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet Global Health. 2018;6:e380–9.

- Gerdts C, Dobkin L, Foster DG, et al. Side effects, physical health consequences, and mortality associated with abortion and birth after an unwanted pregnancy. Women’s Health Issues. 2016;26:55–59.

- Niinimäki M, Suhonen S, Mentula M, et al. Comparison of rates of adverse events in adolescent and adult women undergoing medical abortion: population register based study. BMJ. 2011;342:d2111.

- Nove A, Matthews Z, Neal S, et al. Maternal mortality in adolescents compared with women of other ages: evidence from 144 countries. Lancet Global Health. 2014;2:e155–64.

- Singh A, Singh A, Thapa S. Adverse consequences of unintended pregnancy for maternal and child health in Nepal. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27:NP1481–91.

- World Health Organization. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008. 6th ed. Geneva: WHO; 2011.

- Eliason S, Baiden F, Yankey BA, et al. Awusabo-Asare K. Determinants of unintended pregnancies in rural Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:261.

- Henshaw SK, Kost K. Parental involvement in minors’ abortion decisions. Fam Plann Perspect. 1992;24:196–207. 213.

- Schwandt HM, Creanga AA, Adanu RMK, et al. Pathways to unsafe abortion in Ghana: the role of male partners, women and health care providers. Contraception. 2013;88:509–517.

- Bankole A, Sedgh G, Oye-Adeniran BA, et al. Abortion-seeking behaviour among Nigerian women. J Biosoc Sci. 2008;40:247–268.

- Geelhoed D, Nayembil D, Asare K, et al. Gender and unwanted pregnancy: a community-based study in rural Ghana. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;23:249–255.

- Oppong-Darko P, Amponsa-Achiano K, Darj E. ‘I am ready and willing to provide the service … though my religion frowns on abortion’. Ghanaian midwives’ mixed attitudes to abortion services: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(12):1501.

- Aniteye P, Mayhew SH. Shaping legal abortion provision in Ghana: using policy theory to understand provider-related obstacles to policy implementation. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:23.

- Yamane T. Statistics: an introductory analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Harper and Row; 1967.

- Sullivan GM, Artino AR. Analyzing and interpreting data from Likert-type scales. J Grad Med Educ.2013;5:541–542.

- Sedgh H (2010). Abortion in Ghana. [cited 2018 Dec 12]. Available from: www.guttmacher.org/report/abortion-ghana.

- Rominski SD, Darteh E, Dickson KS, et al. Attitudes toward abortion among students at the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. Sex Reprod Healthcare. 2017;11:53–59.

- Rominski SD, Gupta M, Aborigo R, et al. Female autonomy and reported abortion-seeking in Ghana, West Africa. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;126:217–222.

- Konney TO, Danso KA, Odoi AT, et al. Attitude of women with abortion-related complications toward provision of safe abortion services in Ghana. J Women’s Health (Larchmt). 2009;18:1863–1866.

- Gordon CP. Adolescent decision making: a broadly based theory and its application to the prevention of early pregnancy. Adolescence. 1996;31:561–584.

- Gyesaw NYK, Ankomah A. Experiences of pregnancy and motherhood among teenage mothers in a suburb of Accra, Ghana: a qualitative study. Int J Women’s Health 2013;5:773–780.

- Bain LE, Zweekhorst MBM, Amoakoh-Coleman M, et al. To keep or not to keep? Decision making in adolescent pregnancies in Jamestown, Ghana. PLOS One. 2019;14:e0221789.

- Rehnström Loi U, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Faxelid E, et al. Health care providers’ perceptions of and attitudes towards induced abortions in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia: a systematic literature review of qualitative and quantitative data. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:139.

- Wheeler SB, Zullig LL, Reeve BB, et al. Attitudes and intentions regarding abortion provision among medical school students in South Africa. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;38:154–163.

- Ott MA, Crawley FP, Sáez-Llorens X, et al. Ethical considerations for the participation of children of minor parents in clinical trials. Pediatr Drugs. 2018;20:215–222.

- Adewunmi AA, Etti EA, Tayo AO, et al. Factors associated with acceptability of child adoption as a management option for infertility among women in a developing country. Int J Women’s Health. 2012;4:365–372.