Abstract

Purpose

Available evidence highlights unmet needs in contraceptive counselling practices. This study aimed to understand current practises and clinician behaviour across Europe.

Methods

A novel, online approach was used to simulate contraceptive counselling discussions based on three, predefined patient types with a hidden need: poor compliance (patient X), headaches (Y) or desire for a hormone-free option (Z). Clinicians were asked to provide guidance about a contraceptive method for their randomly assigned patient at two time points: (1) after a simulated discussion, (2) after seeing a full patient profile. Descriptive statistical analyses included evaluation of the clinicians’ counselling approach and a change in contraceptive recommendation thereof.

Results

Out of 661 clinicians from 10 participating European countries, including obstetricians/gynaecologists, midwives and general practitioners, most failed to uncover patient X and Y’s hidden needs (78.8% and 70.5%, respectively), whereas, 63.4% of clinicians uncovered patient Z’s hidden need. Clinicians who uncovered their patients’ hidden needs asked significantly more questions than those who did not (range of mean, 5.1–7.8 vs 1.5–2.2 respectively). Clinicians were more likely to recommend a change of prescription after seeing the full patient profile than after the simulated discussion (increase in prescription change, range: 12.3–30.2%), indicating that clinicians rely on patients speaking up proactively about any concerns.

Conclusions

Insufficient existing counselling practices result in missed opportunities for shared decision-making and discussion. Clinicians and contraceptive counselling services should empower women by introducing more in-depth contraceptive counselling, incorporating clear, open-ended questions, to improve patient adherence and enhance reproductive planning.

摘要

目的:现有证据表明医生在避孕咨询中并未满足患者的需求。本研究旨在了解整个欧洲的临床医生在当前临床实践中的不同行为方式的结果。

方法:使用一种新颖的在线联网方式来模拟避孕咨询。该讨论方法设定三类隐藏真实需求的患者类型:依从性差(X)、头痛(Y)或希望选择非激素者(Z)。医生在两个时间点给随机分配的患者提供有关避孕方法的指导:(1)模拟讨论之后(2)看到患者完整的资料之后。描述性统计分析包括评估医生的咨询方法及改变避孕方式的建议。

结果:来自10个参与研究的欧洲国家 661名临床医生中, 包括产科医生/妇科医生、助产士和全科医生, 大多数医生未发现患者 X 和 Y 的隐藏需求(分别为 78.8% 和 70.5%), 而 63.4% 的医生发现了患者 Z 的隐藏需求。发现患者隐藏需求的医生比没有发现患者隐藏需求的医生提出的问题要多很多(平均值分别为 5.1-7.8 和 1.5-2.2)。与模拟讨论组相比, 医生在查看完整的患者资料后更有可能建议更改处方(增加范围:12.3-30.2%), 这表明临床医生更多依赖患者的主诉。

结论:现有的避孕咨询不足会导致错过共同决策和讨论的机会。医生和避孕咨询服务机构应通过引入更深入的避孕咨询、思路清晰、开放式的问题来提高患者避孕的依从性并做好计划生育。

Introduction

Advances in contraceptive methods over recent decades mean that there are now numerous options available to women, each offering different benefits. When selecting a contraceptive method, women may be influenced by many factors, including reliability, frequency of use, risk of thrombosis, bleeding profile, side-effect profile, pain relief, acne relief, hormone dose and convenience [Citation1,Citation2]. However, for women to be able to assess which contraceptive method best suits their individual needs, they must rely on health care professionals (HCPs) correctly understanding those needs and, based on those needs, providing them with accurate information and an appropriate contraceptive recommendation [Citation1,Citation3].

Current recommendations for optimal contraceptive counselling practice include an open dialogue between HCPs and women seeking contraception, with shared decision-making [Citation1,Citation3–5]. In an effort to optimise this interaction between HCPs and women, numerous structured contraceptive counselling tools have been developed [Citation6,Citation7]. The ‘Contraception: HeLping for wOmen’s choicE’ (CHLOE) questionnaire, for example, elicits information on the woman, any relevant health conditions, and the woman’s needs and preferences, which is then shared with the HCP to facilitate choice of the most appropriate contraceptive option [Citation7]. This tool also provides women with a brief explanation of a range of different methods, recognising that women may not be familiar with all contraceptive methods and that even if they have a specific contraceptive method in mind, they still appreciate learning about alternatives [Citation1,Citation3]. Indeed, findings from the European CHOICE study, which investigated the influence of comprehensive, leaflet-based counselling on women’s selection of combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs), showed that nearly half of women who consulted their HCP about CHCs selected a different method from that originally planned after receiving counselling [Citation8].

In addition to a gap in the understanding of women’s needs on the part of individual HCPs, national frameworks regarding contraceptive counselling practice recommendations are lacking, with inconsistent emphasis placed on the importance of effective contraceptive counselling across Europe [Citation9]. The recent Barometer of Women’s Access to Modern Contraceptive Choice study, which assessed the quality of sexual and reproductive care across 16 European countries, found that several countries had neither a national requirement nor a recommendation for individualised counselling [Citation9]. Furthermore, among those countries that did have nationally recognised minimum standards on individualised counselling, those standards were not always considered to be fully applied. In several countries, no appropriate training on individualised counselling existed, either as part of the medical curriculum or in the form of postgraduate training programmes [Citation9]. This raises concerns about both the quality of contraceptive care and about the appropriateness of the contraceptive recommendations that women are receiving. Highlighting this concern, Lauring et al. looked at CHC use in reproductive-age women with and without contraindications to oestrogen use and found that there was no statistically significant difference between the proportion of women in each group receiving CHCs (39% with contraindications compared with 47% without contraindications) [Citation10].

Recognising the apparent disconnect between women’s needs and HCPs’ understanding of these needs, and in light of the inadequacies in certain national frameworks regarding requirements and training for individualised counselling practices, this study was conducted using a novel online approach to simulate counselling discussions in order to better understand current contraceptive counselling practices and behaviour of HCPs across Europe. The aim of the study was to understand the current counselling behaviour of HCPs, including how they determine and assess patient needs, and how this affects their contraceptive recommendation.

Methods

Design and data collection

This was a market research survey conducted in accordance with the EphMRA Code of ConductFootnote1. Data collection occurred from 13 November 2019 to 5 March 2020 across 10 European countries: Belgium, Finland, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom (UK). Country selection was informed by the need to achieve a culturally diverse sample that included a variety of counselling landscapes (e.g., obstetrician/gynaecologist- vs general practitioner- and midwife-based counselling). Nine countries (Belgium, Finland, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and UK) were selected for a more detailed country-specific analysis on current contraception utilisation and HCP-reported patient preferences. Data from Germany is excluded from the country-specific analysis owing to a similar parallel study being conducted in Germany; both studies have since concluded.

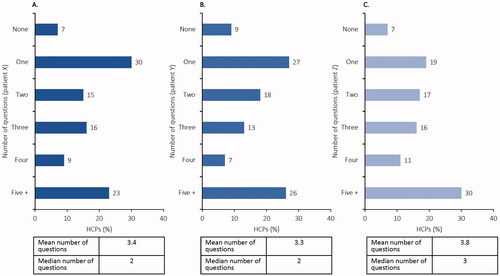

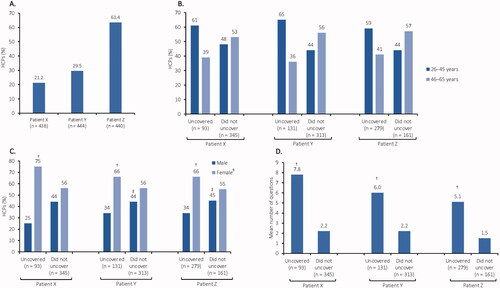

The sampling frame for the study, including country-specific sample target groups, was agreed upon prior to the start of the Primary Market Research. HCPs within the respective country-specific target group were asked to participate in a 40-min online survey (with country-specific customisations), which included the following: (1) a simulation-based patient consultation, which was designed to elucidate the step-by-step decision-making process that HCPs go through when making contraceptive recommendations to their patients (); (2) general questions on personal (e.g., age, sex) and professional (e.g., years in practice, practice setting) characteristics; and (3) questions on HCP attitude/approach to contraceptive counselling. HCPs were screened and recruited into the respective sample target groups based on the results from the above-mentioned survey, with the final selection made based on country-specific criteria such as years in practice, percentage of time spent in direct out-patient care, number of patients of reproductive age currently using a prescription contraceptive and personal experience with contraceptive prescription and placement. For a full list of questions asked in the survey, see Supplementary file 1.

Figure 1. Annotated schematic showing each step in the counselling simulation. The simulation was designed to elucidate the step-by-step decision-making process HCPs go through when making contraceptive recommendations to their patients. *Please see for the list of predefined questions. HCP: health care professional; IUD: intrauterine device; IUS: intrauterine system; OC: oral contraceptive.

Patient profiles

The simulation-based patient consultation was structured around three predefined patient types (patients X, Y and Z). At the start of the consultation, each HCP was randomly assigned a patient type and presented with a brief profile (, part A). Each patient had one key dissatisfaction with her current contraceptive method that was not mentioned in the brief profile presented to the HCP. If the HCP asked the relevant questions during the consultation, they would be able to uncover this ‘hidden need’; however, HCPs were otherwise unaware of the needs’ existence. Key needs for each patient type, and the questions that would most directly identify those needs, were as follows:

Table 1. Patient characteristics and counselling questions.

Patient X struggled with compliance (Q: ‘How many times did you forget to take the pill over the last 3 months?’ A: ‘Maybe once or twice.’)

Patient Y suffered from headaches (Q: ‘With your current pill, do you experience anything you are not happy with?’ A: ‘I have more headaches than before and I guess it may be related to the pill, but I am not sure.’)

Patient Z wanted to be sure she would not get pregnant and wanted to avoid hormones (Q: ‘What is important to you when choosing a contraceptive method?’ A: ‘I need to be sure I will not get pregnant and I don’t want hormones. I’m convinced they are not good for my body.’)

Further information about each patient could be uncovered by the HCP through questioning to give a full patient profile (, part B).

Simulation-based patient consultation

The consultation was structured in two parts: (1) simulated discussion and (2) complete information (). At the end of the second part of the consultation, the entire process was repeated, and the HCP was presented with a second, predefined, randomly assigned patient type.

Part 1: simulated discussion

A full, annotated breakdown of the simulated discussion is shown in . The simulated discussion was designed to focus on how each HCP interacted with their patient based on the information that was available in the brief patient profile, and what the HCP recommended as a result of that discussion. The open-ended questioning at the start of the discussion gave an insight into the types of questions typically asked by HCPs in a consultation, and how those questions differed according to the patient type. The aided questioning that followed used a predefined question list (, part B) and enabled the number, type and sequence of questions asked for each patient type to be analysed. After each question from the list was asked, the patient’s response was shown (, part B), and the HCP was given the option of either recommending a contraceptive or continuing with the questioning (until all questions had been exhausted) to obtain more information. The simulated discussion finished once the HCP had made a contraceptive recommendation and specified which patient characteristics had influenced their decision.

Part 2: complete information

The full breakdown for the complete information part of the consultation is shown in . This part of the consultation was designed to examine whether the HCP’s recommendation changed once they had been presented with the full patient profile (i.e., with all the additional information that could have been obtained through questioning). Having viewed the patient profile, the HCP was asked again what contraceptive they would like to prescribe to the patient, to determine whether having more information would make the HCP re-evaluate their original decision. This part of the consultation finished once the HCP had chosen either to stick with their original recommendation or to make a new contraceptive recommendation (stating what the new recommendation would be) and specified which patient characteristics had influenced their decision.

Statistical analysis

Results were analysed using descriptive statistical methods, mainly measures of central tendency (mean, median and frequency distributions) and measures of dispersion (standard deviation and standard error) for open numeric/rating scale questions. Significance between means and proportions was tested using a T-test. In cases where results are presented by respondent groups, the statistical significance of the differences between data was determined at the 95% confidence level. SPSS® and Microsoft Excel were used to conduct the analysis.

Results

HCP demographics/characteristics

HCP demographics and characteristics are shown in . In total, 661 HCPs participated in the research. HCP speciality differed by country, with the majority being obstetricians/gynaecologists: the only non-obstetrician/gynaecologist respondents came from the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK. In 70% of countries, more respondents were female than male.

Table 2. HCP demographics/characteristics.

Patient X was assigned to 438 HCPs, patient Y to 444 HCPs and patient Z to 440 HCPs.

Women’s needs are often not identified

In the aided questioning, the majority of HCPs did not ask their patient about her plans regarding pregnancy and children, although they were more likely to do so if the patient actively requested a review of her contraceptive choice (asked by 28%, 27% and 43% of HCPs for patients X, Y and Z, respectively). Approximately three-quarters of HCPs (range, 74–77%) across the participating countries did not specifically ask their patient if there was anything she was unhappy with in relation to her current contraception, <20% asked about compliance, and 2–15% (range) asked about current/preferred bleeding intensity.

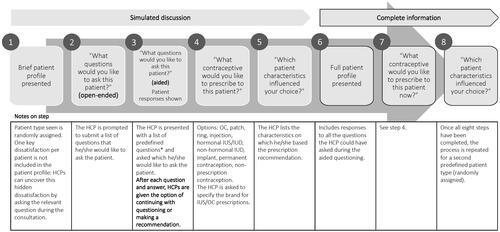

The majority of HCPs (78.8% and 70.5%, respectively) assigned to patients X and Y, who had requested prescription renewals, failed to uncover the hidden needs of their patient (poor compliance and headaches, respectively). By contrast, for patient Z, who had actively requested a review of her contraceptive method, 63.4% of clinicians uncovered the hidden need (desire for a hormone-free option) ().

Figure 2. Identification of women’s needs during contraceptive counselling. (A) Proportion of HCPs who identified their patient’s hidden need during contraceptive counselling. *Women’s needs were often not identified but were more likely to be identified when the patient actively requested a review of her contraceptive method. (B) Identification of patient hidden needs according to HCP age. (C) Identification of patient hidden needs according to HCP sex. (D) Mean number of questions asked by HCPs. HCPs who uncovered hidden needs were more likely to be younger (B), female (C) and ask more questions (D) than those who did not. *N values represent the number of HCPs who were assigned that patient’s profile. †Significantly higher than ‘Did not uncover’ at 95% CI. ‡Significantly higher than ‘Uncovered’ at 95% CI. §Females accounted for 46–100% of respondents per country; in 7/10 countries, more respondents were female than male. CI: confidence interval; HCP: health care professional.

HCPs who uncovered hidden needs were more likely to be younger, female, ask more questions during counselling and switch the patient from her current contraceptive ().

HCPs rely on women to speak up proactively

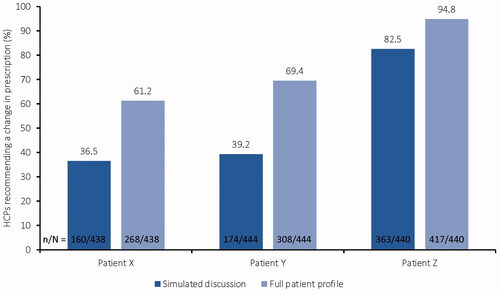

HCPs were more likely to recommend a change of prescription once they had been presented with the full patient profile than when they were at the end of the first part of the consultation, after the simulated discussion (). More HCPs changed the prescription of patient Z, who actively requested a review of her contraceptive method, than they did for patients X and Y, who simply requested a prescription renewal.

Figure 3. Proportion of HCPs recommending a prescription change before and after seeing the full patient profile. HCPs were more likely to recommend a change in prescription after obtaining a better understanding of their patients’ needs. HCP: health care professional.

For patients Y and Z, HCPs who did not uncover the hidden needs were more likely to change their patient’s prescription once they had seen the full patient profile than those who uncovered such needs (, Supplementary file 2). For all patient profiles, HCPs who uncovered their patient’s hidden need during the simulated discussion recommended a change in prescription at an earlier point in the consultation than those who did not identify their patient’s hidden need. By contrast, HCPs who did not uncover their patient’s hidden need were more likely to keep the patient on her current prescription compared with those who did uncover their patient’s hidden need (Figure S1, Supplementary file 2).

Consultations with patients X and Y, who did not actively request a review of their prescription, were shorter than those with patient Z (). Less than half of HCPs asked patients X and Y three or more questions (48% and 46%, respectively) compared with 57% for patient Z. In total, 41% of HCPs felt that women would state clearly if they had any issues with their current contraceptive method.

HCPs do not follow a structured counselling approach

The open-ended questioning during the simulated discussion revealed that patients X and Y, who had not requested a review of their contraceptive method, were more likely to be asked high-level questions about satisfaction than patient Z, whereas patient Z was more likely to be asked about family planning/pregnancy timing than patients X and Y (Table S1, Supplementary file 3).

In the aided questioning, the sequence of questions asked was highly variable across HCPs. Questions asked tended to have a closed nature, requiring only a ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ answer, e.g., for both patients X and Y, the majority of HCPs opened the consultation by asking: ‘Are you OK with your pill?’

Attitudes of HCPs regarding current counselling behaviour

Although few HCPs uncovered their patient’s hidden needs in the simulated consultation, most HCPs felt that, in general, they have enough time for counselling. The majority of HCPs (72%) felt that it is their responsibility to guide the patient’s decision on what best suits her needs; however, HCPs also generally felt that the ultimate decision lies with the patient.

Country-specific insights

Data on prescription landscape by country, including contraceptive status of patients seen in the last month and split between long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) and non-LARC prescriptions, are shown in the Supplementary information (Table S2, Supplementary file 4).

HCP-reported patient preferences were similar across all nine countries included in the country-specific analysis. A quarter or more of HCPs from all countries except Switzerland noted an increasing preference for LARCs among their patients, although this increasing preference did not detract from the popularity of oral contraceptives.

Discussion

Findings and interpretation

This European survey-based study used a novel, simulation-based patient consultation to understand the current counselling behaviour of HCPs. The results of the study highlight a clear need for more in-depth contraceptive counselling in clinical practice and suggest that existing counselling practices are insufficient to capture patient needs, with opportunities for shared decision-making and discussion being missed.

A key focus of contraceptive counselling sessions should be on reproductive planning, in terms of desire (or lack of desire) for future pregnancy, and the associated timelines [Citation11,Citation12]. While this discussion is central to contraceptive choice (e.g., LARC versus non-LARC), it also provides HCPs with the opportunity to help women to fully prepare for their reproductive choice and to establish rapport and understanding with the patient. It is well acknowledged that patients value having a shared understanding with their HCP [Citation11,Citation13,Citation14] and that by establishing this relationship with their patients, HCPs can help to improve clinical outcomes, e.g., through increased patient adherence [Citation13–15]. The present study showed that reproductive planning and bleeding patterns were infrequently discussed with all patient types, although reproductive planning gained higher priority when the patient was actively looking to re-evaluate her contraceptive options.

An additional benefit of establishing a close patient–HCP relationship is that it is likely to encourage patients to speak up proactively about their needs and concerns. The present study found that the hidden need of patients X and Y was not uncovered by the majority of HCPs, indicating that HCPs rely on women to actively state if they have any concerns with their choice of contraception. Furthermore, nearly half of HCPs commented that they would expect their patients to clearly specify if they were experiencing any problems with their contraceptive method. However, evidence shows that this is an unrealistic expectation, with many women not knowing that the menstrual and other symptoms they experience could be improved with a different contraceptive choice and some women feeling too embarrassed to discuss certain side effects, e.g., combined oral contraceptive (COC)-related loss of libido, with their HCP [Citation16–20]. It is therefore important both for HCPs to ask their patients open-ended questions, to help trigger a discussion, and, more importantly, for patients to be actively encouraged to speak up during consultations.

In the present study, the proactive approach of patient Z triggered a counselling ‘discussion’ that led to the majority of HCPs identifying her hidden need. By contrast, the passive approach of patients X and Y failed to stimulate an in-depth discussion, which, in most cases, resulted in the patients’ hidden needs remaining unidentified. By personally reflecting on their contraceptive and reproductive planning needs and determining any symptoms that may be related to their current contraceptive method, patients increase their chances of being prescribed the most appropriate method and any issues being identified and resolved. To enable this, and to adequately prepare them for discussions with their HCP, patients should be provided with sufficient information on the different contraceptive methods and their potential effects on important aspects of daily life. Empowering women in this way would additionally enable HCPs to start a targeted counselling discussion on issues relevant to the individual patient, thus reducing the time needed for the consultation.

In the present study, identification of the hidden needs of the patient led to significant changes in the pattern of methods being prescribed by the HCP, indicating that HCPs are adept at meeting patient needs once those needs have been identified.

Across Europe, there are regional variations in contraceptive use, both in terms of reliance on any form of contraception and the availability of/preference for specific methods [Citation1,Citation21,Citation22]. While regional differences were not notable in the present study, they should still be taken into account in contraceptive counselling practice. All contraceptive counselling should aim to dispel any misperceptions that may be preventing contraceptive use and to educate patients on the non-contraceptive benefits of the different contraceptive methods [Citation22,Citation23], but this is particularly important in those regions where women may be reluctant to engage with any form of contraception. By proactively providing relevant information and enhancing women’s all-round understanding of the potential benefits of contraceptive methods – including improvements in quality of life, menstrual symptoms and heavy menstrual bleeding [Citation15,Citation20,Citation24] – women will better actively contribute to the contraceptive decision-making process and choose a contraceptive method that best meets their individual needs.

Strengths and weaknesses

Although the present study provides useful insights into counselling practices across Europe, it has some limitations. First, the simulated discussion was designed to mimic a real consultation as closely as possible; however, the artificial and computer-generated nature of the patient responses meant that the discussion did not truly reflect HCP behaviour in terms of rapport and relationship-building, and there was no pre-existent relationship between the HCP and the patient. Second, it was necessary to avoid over-exposing the HCPs to the study method to prevent them from second-guessing the desired/expected outcomes and asking questions for the sake of asking questions. This limited the design of patient type that could be presented to the HCPs: it had to be wide enough to capture a multitude of existing patient profiles, yet narrow enough not to interfere with the simulation of a true conversation. Third, the breadth of data gathered, e.g., from counselling practice insights to specific method and brand adoption parameters, fragmented the focus of the analysis, which would not have been the case with a more limited scope. However, this research is only a starting point and can be built upon in future studies with greater statistical power, including the addition of new patient types. Fourth, all three fictional patients used for the simulated discussion were presented as users of COCs and might not reflect the broad range of contraceptive methods used in real-world scenario. However, the HCP survey results on the contraceptive status of patients seen in the last month in this study indicate a high proportion of non-LARC utilisation. Moreover, a 2019 United Nations report indicates high prevalence of non-LARC contraceptive methods including oral contraceptive pill in European countries compared with LARC methods [Citation25]. Finally, although there are similarities in practice across Europe, caution should be applied if extrapolating these results to countries not included in the survey due to variations in sociocultural backgrounds and health care systems.

Similarities and differences in relation to other studies

In agreement with the current study, recent studies have shown that there is a disconnect between women’s contraceptive needs, both in terms of method attributes (e.g., reliability, safety and cost) and HCP counselling practices, and the understanding of those needs by HCPs [Citation1,Citation11]. Findings from the European TANCO survey, which explored women’s and HCPs’ views on aspects of counselling around contraception and contraceptive use, showed that HCPs tended to underestimate women’s interest in receiving information about all contraceptive methods [Citation1]. HCPs also had different perceptions to the women regarding the importance of different contraceptive attributes [Citation1]. A study in the US investigated information priorities of women for their contraceptive decision-making and HCPs for contraceptive counselling [Citation26]. Inconsistency in some areas of information priority was noted between women and HCPs indicating the need for improved patient-centred contraceptive counselling [Citation26]. Moreover, a global think tank consisting of a broad range of experts including the World Health Organisation, identified significant knowledge gap in many areas of contraceptive counselling and effective implementation tools [Citation27].

Open questions and future research

HCPs and contraceptive counselling services should make efforts to introduce more in-depth contraceptive counselling, incorporating clear, open-ended questions, to improve patient adherence and enhance reproductive planning. Currently, high-quality evidence is lacking with no clear consensus on the best possible method for delivering contraceptive counselling in order to meet user satisfaction [Citation27]. Future research is warranted to develop tools and efficient ways to improve contraceptive counselling.

Conclusions

Existing counselling practices are insufficient to capture patient needs, with opportunities for shared decision-making and discussion being missed. Additionally, women should be empowered to actively voice their needs and any dissatisfaction with their current contraceptive method. This can be achieved through the development of easily understandable, patient-oriented tools that provide information on contraceptive methods and allow women to reflect on and identify their own individual contraceptive needs. Such an approach would also make contraceptive counselling easier and less time-consuming for HCPs.

Ethical approval

This market research survey was conducted in accordance with the EphMRA Code of Conduct. All survey respondents provided written voluntary and informed consent to, and confirmed awareness of, data collection and its use as part of completing the online survey. Institutional Review Board (IRB)/Ethics Committee approval was not required for this study as per the EphMRA Code of Conduct for market research studies.

Author contributions

REN, NV and RB contributed to the study design. REN, NV and RB contributed to the data analysis and data interpretation. REN, NV and RB provided input into the drafting and revision of this manuscript, and all read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary File 4. Table S2

Download PDF (63.3 KB)Supplementary File 3. Table S1

Download PDF (57.8 KB)Supplementary File 2. Figure S1

Download PDF (60.6 KB)Supplementary File 1. Online survey

Download PDF (191.5 KB)Disclosure statement

Rossella Nappi: Past financial relationships (lecturer, member of advisory boards and/or consultant) with Boehringer Ingelheim, Ely Lilly, Endoceutics, Gedeon Richter, HRA Pharma, Procter & Gamble Co, TEVA Women’s Health Inc and Zambon SpA. At present, she has an ongoing relationship with Astellas, Bayer HealthCare AG, Exceltis, Fidia, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Novo Nordisk, Palatin Technologies, Pfizer Inc, Shionogi Limited and Theramex.

Nicky Vermuyten: Employee at Bayer.

Ralf Bannemerschult: Employee at Bayer.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study, where not included in this published article and its supplementary information files, are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The EphMRA Code of Conduct is a mandatory guideline comprising 12 guiding principles and forms the basis of ethical market research in pharmaceuticals. These principles include voluntary and informed consent to data collection and awareness of its use by each respondent.

References

- Merki-Feld GS, Caetano C, Porz TC, et al. Are there unmet needs in contraceptive counselling and choice? Findings of the European TANCO Study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2018;23(3):183–193.

- Egarter C, Frey Tirri B, Bitzer J, et al. Women’s perceptions and reasons for choosing the pill, patch, or ring in the CHOICE study: a cross-sectional survey of contraceptive method selection after counseling. BMC Womens Health. 2013;13:9.

- Dehlendorf C, Levy K, Kelley A, et al. Women’s preferences for contraceptive counseling and decision making. Contraception. 2013;88(2):250–256.

- Merckx M, Donders GG, Grandjean P, et al. Does structured counselling influence combined hormonal contraceptive choice? Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2011;16(6):418–429.

- Bitzer J, Marin V, Lira J. Contraceptive counselling and care: a personalized interactive approach. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2017;22(6):418–423.

- Cavallaro FL, Benova L, Owolabi OO, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of counselling strategies for modern contraceptive methods: what works and what doesn’t? BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2020;46(4):254–269.

- Jamin CG, Hausler G, Lobo Abascal P, et al. Development and conceptual validation of a questionnaire to help contraceptive choice: CHLOE (Contraception: HeLping for wOmen’s choicE). Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2017;22(4):286–290.

- Bitzer J, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Roumen F, et al. The CHOICE study: effect of counselling on the selection of combined hormonal contraceptive methods in 11 countries. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2012;17(1):65–78.

- IPPF European Network. Barometer of women’s access to modern contraceptive choice in 16 EU countries 2015. [cited 2020 June]. Available from: https://www.ippfen.org/sites/ippfen/files/2017-04/IPPF%20EN%20Barometer%202015%20contraceptive%20access.pdf

- Lauring JR, Lehman EB, Deimling TA, et al. Combined hormonal contraception use in reproductive-age women with contraindications to estrogen use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):330.e1–330.e7.

- Dehlendorf C, Krajewski C, Borrero S. Contraceptive counseling: best practices to ensure quality communication and enable effective contraceptive use. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;57(4):659–673.

- Dehlendorf C, Henderson JT, Vittinghoff E, et al. Association of the quality of interpersonal care during family planning counseling with contraceptive use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):78.e1–78.e9.

- Kennedy BM, Rehman M, Johnson WD, et al. Healthcare providers versus patients’ understanding of health beliefs and values. Patient Exp J. 2017;4(3):29–37.

- Cooley L. Fostering human connection in the covid-19 virtual health care realm. N Engl J Med. 2020;1–6. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/CAT.20.0166

- Nappi RE, Kaunitz AM, Bitzer J. Extended regimen combined oral contraception: a review of evolving concepts and acceptance by women and clinicians. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016;21(2):106–115.

- Bitzer J. Hormone withdrawal-associated symptoms: overlooked and under-explored. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(6):530–535.

- Bitzer J, Serrani M, Lahav A. Women’s attitudes towards heavy menstrual bleeding, and their impact on quality of life. Open Access J Contracept. 2013;4:21–28.

- Sulak PJ, Scow RD, Preece C, et al. Hormone withdrawal symptoms in oral contraceptive users. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(2):261–266.

- de Castro Coelho F, Barros C. The potential of hormonal contraception to influence female sexuality. Int J Reprod Med. 2019;2019:9701384.

- Iacovides S, Avidon I, Baker FC. What we know about primary dysmenorrhea today: a critical review. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(6):762–778.

- Dereuddre R, Van de Putte B, Bracke P. Ready, willing, and able: Contraceptive use patterns across Europe. Eur J Popul. 2016;32(4):543–573.

- Bitzer J, Abalos V, Apter D, et al. Targeting factors for change: contraceptive counselling and care of female adolescents. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016;21(6):417–430.

- Nappi RE, Pellegrinelli A, Campolo F, et al. Effects of combined hormonal contraception on health and wellbeing: women’s knowledge in Northern Italy. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2015;20(1):36–46.

- Sriprasert I, Pakrashi T, Kimble T, et al. Heavy menstrual bleeding diagnosis and medical management. Contracept Reprod Med. 2017;2:20.

- United Nations. Contraceptive use by method 2019. [Sept 2021]. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2020/Jan/un_2019_contraceptiveusebymethod_databooklet.pdf.

- Donnelly KZ, Foster TC, Thompson R. What matters most? The content and concordance of patients’ and providers’ information priorities for contraceptive decision making. Contraception. 2014;90(3):280–287.

- Ali M, Tran NT, Kabra R, et al. Strengthening contraceptive counselling: gaps in knowledge and implementation research. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2021:1–3. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsrh-2021-201104