Abstract

Purpose

Health care professionals’ attitudes and behaviours play a fundamental role in the provision of timely comprehensive abortion care as a maternal health intervention and save hundreds of thousands of women’s lives, annually. This study explores underlying factors influencing Tanzanian and Ethiopian health care professionals’ attitudes and behaviours towards comprehensive abortion care between 2015 and 2020.

Materials and methods

The study inductively explored Ethiopian and Tanzanian health care professionals’ behaviours using a comparative case study design and a textual analytical approach. Published and unpublished literature, documents and newspapers were used as data sources. The two cases were selected because of their different approaches towards the governance of abortion care, one gradually legalising while the other persistently restricting.

Results

Results demonstrated that there are both subjective (beliefs, attitudes, images, pre-dispositions) and objective (institutional incapacity) factors that impact the actions of health care professionals in the work environment.

Conclusions

The study concluded that the intervention of subjective factors results from the institutional failure to effectively bridge the divide between governance and accessibility of safe abortion care.

摘要

目的:卫生保健专业人员的态度和行为在提供及时的综合堕胎护理中发挥着根本作用, 其作为产妇健康干预措施, 每年挽救数十万女性的生命。本研究探讨了2015年至2020年间影响坦桑尼亚和埃塞俄比亚卫生保健专业人员对综合堕胎护理的态度和行为的潜在因素。

材料和方法:本研究采用对比案例研究设计和文本分析方法, 对埃塞俄比亚和坦桑尼亚卫生保健专业人员的行为进行归纳研究。数据来源于已发表和未发表的文献、文件和报纸。之所以选这两个国家, 是因为它们对堕胎护理的管理方式不同, 一个逐渐将堕胎合法化, 另一个持续限制堕胎。

结果:结果表明, 影响卫生保健专业人员在工作环境中行为的因素既有主观因素(信仰、态度、形象、倾向), 也有客观因素(机构无许可)。

结论:该研究得出结论, 主要影响因素是机构未能有效跨过制度和可获得安全堕胎护理之间的鸿沟。

Introduction

As a maternal health intervention, comprehensive abortion care (CAC) is critical for reducing avoidable maternal morbimortality. Between 2015 and 2019, WHO [Citation1] estimated that 73.3 million combined incidences of safe and unsafe abortions were recorded globally, and 97% were recorded in low-to-medium-income countries (LMIC). However, evidence shows that these occurrences are significantly higher in restrictive settings which leads to inaccessibility and widening of the CAC unmet need gap [Citation2]. Health care professionals’ unacceptance of CAC as a critical maternal health intervention also exacerbates the inaccessibility problem facing women globally [Citation3–6].On the other hand, acceptance substantially increases the timeliness of provision and is as equally important as institutional and legislative efforts to increase accessibility [Citation3,Citation5,Citation6].

Studies show that neither restrictive nor liberalised abortion policies can reduce the occurrences of unsafe abortions alone due to the interference of human subjective factors [Citation3,Citation7]. On the one hand, restrictive policies do not stop abortions from happening but only pushes them to unsafe environments [Citation3]. On the other hand, care centres and professionals invoke conscientious objections even when women are allowed to receive abortion care [Citation3,Citation5]. The above two issues point to the divide between policy principles and the practical problems these policies intend to address. Keogh et al. [Citation3] and MacFarlane et al.’s [Citation5] argue that policy measures and the political climate in a given context either facilitate or hinder provision. Subsequently, at the juncture where accessibility meets acceptability, overlapping professional responsibilities and personal characteristics lead to dilemmas and unnecessary delays [Citation5].

Though previous research identifies a relationship between health care professionals’ predispositions and their subsequent behaviours, there is not enough discussion on why some professionals tend to deviate from certain socio-cultural norms and their own affirmed beliefs or why some display double-standards. Hence, this study aims to describe and interpret factors influencing health care professionals’ attitudes and behaviours towards CAC and find out how they facilitate or inhibit provision in two countries from the same region.

Material and methods

The study used an adapted version of the methodology for scoping reviews [Citation8] to carry out a comparative case study [Citation9] of Ethiopia and Tanzania. By taking this methodological approach, the study cannot be classified as a literature review because of the way it compares two cases [Citation9], integrates other bodies of evidence [Citation10] and the in-depth interpretive textual analysis [Citation11,Citation12].

The chosen approach allowed the study to explore and describe factors influencing health care professionals’ attitudes and behaviours towards abortion care. The WHO’s Expanding health worker roles for safe abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy framework was used to guide the review [Citation13]. The framework identifies which type of health personnel are in question (who), which type of abortion care service is in question (what) and in which environment is the abortion care performed (where) [Citation13].

Case selection

Two typical representatives of the abortion discourse in the Eastern Africa region, one restrictive (Tanzania) [Citation14] and the other increasingly liberalising (Ethiopia) were chosen [Citation9,Citation15]. The two cases present a unique opportunity for academia to understand patterns, similarities, and differences across countries from the same region, with somewhat similar cultures and beliefs [Citation16].

Types of sources

Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods and other bodies of evidence were considered for inclusion, except for reviews due to methodological reasons which are incongruent with this study. Other textual material often excluded from orthodox systematic reviews were considered because all forms of texts are discourses, not written in isolation, but are in a relationship and communicate with each other [Citation12]. Taking this unorthodox approach reveals the world beyond words, symbols, and texts and facilitates an understanding of the broader picture these textual discourses are painting concerning the research problem [Citation12].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The Population, Intervention, Comparators, Outcomes and Study Design (PICOS) framework was used to define the inclusion, exclusion criteria, and derive keywords [Citation17]. Studies that included abortion care provided by qualified health care providers between 2015 and 2020 were included using the WHO Framework on expanding health worker roles for safe abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy [Citation13] (Appendix 1) and only professionals, recipients and informants working with the abortion topic were included.

Information sources

The search was conducted by the first author between February and April 2021 from online databases and platforms such as PubMed, Google Scholar, Taylor and Francis, cross-references, and hand-search. Attempts to request for transcripts of interviews and other primary data sources yielded no results.

The search strategy aimed to locate both published, unpublished studies and newspaper articles on the topic. An initial limited search of PubMed, Google Scholar was undertaken to identify articles on the topic using adapted search strategy for each database (Appendix 2). Words contained in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles, and the index terms used to describe the articles were used to develop a full search strategy. The search strategy, including all identified keywords and index terms, were adapted for each included information source. The reference list of all included sources of evidence was screened for additional studies and provided. Studies published in languages other than English were excluded because of language limitations.

Data extraction

Data was extracted by first author using an adapted version of the JBI data extraction tool [Citation18] (Appendix 3). The JBI Critical Appraisal Tool (Appendix 4) was also used for quality control and to ensure they met their discipline’s standards before integration.

Analysis and presentation

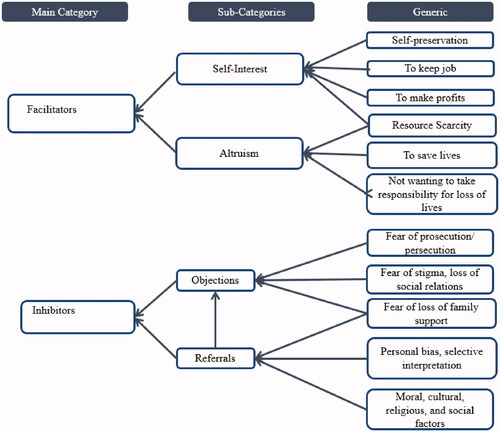

Data were descriptively extracted, entered in the Nvivo [Citation19] and coded. Coded data were then compared [Citation20], first within each case and then across cases to identify patterns, similarities, and differences [Citation9,Citation16]. Data were then reduced by extracting codes into categories and subcategories (). Descriptive components of quantitative studies were, integrated with quotes and summaries from newspaper articles, qualitative and mixed-methods materials.

Table 1. Factors influencing individual attitudes and behaviours.

Factors influencing health care professionals’ behaviours and attitudes were at the centre of the analysis supported by the WHO’s Expanding health worker roles for safe abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy framework [Citation13]. In addition, the analysis adopted an in-depth interpretive and textual analytical approach [Citation12] congruent with and justifying the departure from orthodox literature reviews [Citation8,Citation10]. Finally, the results were descriptively presented and supported by tables and figures.

Ethical considerations

The study used already published material that did not require the researchers to seek ethical approvals. Authors ensured that all included material were ethical and complied with standards of the domain they were sourced from. No ethical concerns were identified, and all materials included were accurately and fairly treated (Appendix 4).

Results

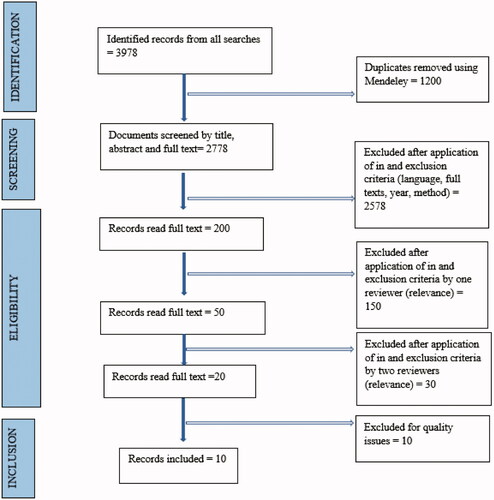

All searches yielded 3978 hits. Identified citations were collated, uploaded into Mendeley [Citation21] and duplicates removed. A pilot test was conducted, titles and abstracts were then screened by first author for assessment against the inclusion criteria. Full texts of selected citations were assessed against the inclusion criteria by first author in discussion with second author. Reasons for exclusion were reported ( and Appendix 1). Disagreements that arose between the authors at each stage of the process were resolved through discussion. The results of the search and the study inclusion process was reported in full and presented in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for scoping review (PRISMA-ScR) flow diagram () [Citation22].

Details of included studies

Ten sources were included, one was a newspaper, and one was a cross-national study including Ethiopia and Tanzania. The latter was treated as a double-entry resulting in a total of 11 sources. Populations used in the sources were assessed according to the inclusion criteria (Appendix 1). Finally, source criticism was carried out qualitatively using the data appraisal tool (Appendix 4) to ensure that all included sources met acceptable standards from their respective domains and included material is reported (Appendix 5).

Results have shown that the way health care professionals behave towards the provision of abortion care in the workplace from both cases can be summed into two main categories of intervening factors, see above.

Ethiopia

Individual characteristics

Some professionals were aware of the constraints presented by their social and professional environments but chose to forgo their predispositions to provide safe abortion services.

I am a Muslim, but I am liberal. We need to save her life. I have seen those who died because I rejected them. I prefer to [perform abortion] because it is a matter of life and death. That is how my logic works. – [Citation23]

Though some professionals could reason away from their religious predispositions and did not use social identities as primary frames informing their actions, they did not attempt to vacate these religious convictions.

I reassure myself when I look at it from the angle of helping. God had said help those who are in need. [Citation23]

The health care worker did not perceive ‘self’ as a product of the social world or permanently affected by professional and cultural factors but as an active agent constantly reflecting on self-positionality, interpreting, and constructing new realities in real-time.

However, some health care professionals demonstrated an unwillingness to depart from the social and religious normative baseline which they used as anchors for their positions against provision.

A right to life begins already at conception or implantation: [The embryo] is a proper person. That is the basis. It has a right to live. It has a right from the moment it is conceived. [Citation23]

Institutional factors

Competence

In-service training increased the knowledge instrumental in increasing the timeliness of safe abortions and professionals’ confidence.

On average, professionals could name 51% of the five immediate complications of unsafe or incomplete abortion. Training to perform MVA (manual vacuum aspiration) and actual provision of MVA in the last three months significantly protected against a lower summary score. [Citation24]

Interpersonal interactions

Interactions were not limited to passive mental processes of negotiating values at the personal level but manifested psychologically through workplace interpersonal interactions with colleagues who held divergent views. Some of these interactions manifested emotionally and some, verbally.

They would jokingly be called “antigeneration” or “child killer” by colleagues who were not performing abortions. The negative perceptions of health professionals providing abortion services caused many to hide the nature of their work. [Citation25]

Exposure

Constant exposure to abortion occurrences and interpersonal factors over extended periods of time in the absence of occupational support also resulted in the change of attitudes.

Previously I was not affected, but now as I am growing older, I sustain some feelings of guilt. Because this is a sin. Nowadays, I do not tell [people] that I work in [the abortion clinic]. [Citation23]

Occupational support

Data also showed that some individuals felt no support from their institutions despite the constant exposure to trauma, emotional, and verbal abuse.

Many felt that they were standing alone with difficult decision-making and missed a support network. [Citation25]

Political and legal factors

Some felt that the legal framework did not address practical issues presenting challenges to health care professionals. Whereas some felt that they had a political backing which subsequently minimised the fear of persecution and prosecution.

We don't think about the limitation. It is allowed. If you talk against abortion in Ethiopia, you are talking against the government. [Citation26]

Tanzania

Personal characteristics

Health care professionals were aware of intersecting professional responsibilities, religious beliefs, social norms, values, and laws which consequently affected their positionality against ‘others’.

I know that it's a sin, I'm Christian, and I know that. Secondly, I know that it's against the law. I feel sorry for them. Sometimes I give them (the drug) because I wouldn't want them to have problems where they will go to terminate the pregnancy. [Citation27]

Individuals weighed in the benefits of saving women’s lives against breaking the law and ‘sinning.’ They understood that without their service, women might resort to unregulated abortion and harmful services. This behaviour did not take away their cognisance of the legal restrictions but motivated them to facilitate provision.

They have broken the law, yes, but at that point, what you need is to provide services. Any aversive action can make them run away from the health facilities that they should be running towards saving their lives. [Citation26]

Some were unwilling to provide family planning services as part of CAC due to their socio-cultural and personal predispositions. Some believed that though abortion was somewhat acceptable, family planning on young women was ‘unfair and inappropriate’.

Emergency treatment is mandatory when the clients' life is in danger, but you can't do long-term contraception to [a PAC client] with a single child. This is unfair. So, it is to be advised to use the appropriate method. [Citation28]

Institutional factors

Competence

Training was not the only factor considered when evaluating the ability to provide safe abortions. Health care professionals were also constantly reflecting on their confidence to provide CAC or refer clients to someone else with better skills. They felt the intervals between in-service training affected their confidence regardless of their willingness to provide the service.

In the long-time lapses before repeating the training, it is likely for one to forget some things. If I cannot continue to provide [MVA for PAC (Postabortion Care)], then I will send the client to this hospital. [Citation28]

Lack of training and adequate knowledge to handle cases also led to health care professionals’ failure to provide sufficient information to clients to make informed decisions.

I wished [the PAC professional] advised me between injection and pills, which is the best… they told me to wait, that I should not start taking family planning drugs now. [Citation29]

Resource scarcity

Shortages in medical supplies affected their ability to handle abortion cases, consequently influencing their behaviours. Shortages in medical resources vis-a-vis service demand resulted in corruption and the collection of bribes.

Most of the time, most of the clients come and find the medications are out of stock, so they have to give out their money and buy these medications, If the items were available, it would have helped to stop the idea of bribery. [Citation28]

Though confidence, knowledge and skills to effectively perform and provide CAC led to in delays and referrals, the general human resource shortage also led to time constraints and the effectiveness of those who could provide.

Time is very limited, you might have gone for performing MVA at the same time the labour ward awaits you, and again you are called to see the new patient in the ward. [time is limited] especially during counselling, just some shallow explanations. She will leave with little knowledge. [Citation28]

Occupational support

Despite the harsh realities of health care professionals’ working environment, which they were constantly exposed to, there were claims of the absence of institutional support mechanisms for those providing the service.

You find that a clinician is working 'round the clock. There is no time to rest, even for a few minutes. This means that there is an acute shortage of staff. There is no motivation given to the staff. [Citation28]

Legal factors

Abortion discourses are politicised and instrumentalised to spread fear in communities and workplaces, which hinder women’s access to timely CAC and affected their framing of the abortion problem.

The Prime Minister ordered that the government would sack practitioners implicated in abortion allegations. He noted that he was informed about practitioners involved in inducing an abortion to students and women within the maternal ward, using government equipment/supplies against the public service ethic. [Citation30]

Regardless of the threats to their careers, health care professionals still provided services even in their limited capacities.

The health professionals interviewed were all aware of the legal restrictions against abortion but nonetheless considered it unethical to deny the benefits of safe, modern abortion methods to what was formulated as victims of unwanted pregnancy. [Citation30]

Providers’ behaviours and attitudes

The above results show that health care professionals behaviours and attitudes in both cases can be classified into two categories, facilitators and inhibitors as demonstrated in below.

Discussion

Findings and interpretation

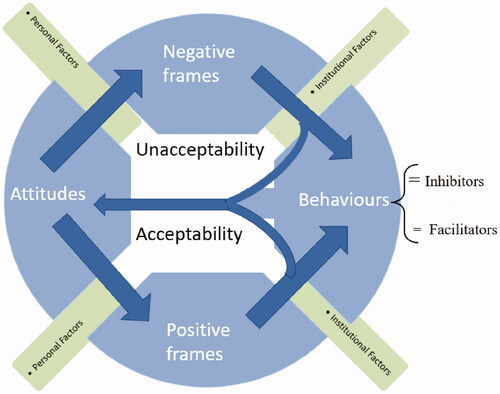

There were two categories of attitudes and behaviours of health care professionals that are influenced by both personal (subjective) and institutional factors. These factors shaped how individuals framed CAC and the subsequent actions taken in the health care setting. However, the influences differed with each country context. Another key observation was that, in both cases, perspectives varied with the type of abortion care in question. For instance, some had no objections to pregnancy termination but due to sociocultural dispositions, objected to family planning as PAC [Citation28].

Personal characteristics

Individuals’ framing of CAC can be influenced by sociocultural predispositions which form the basis for denying provision or by the willingness to depart from these predispositions leading to acceptability of CAC as a maternal health intervention. While accessibility of CAC services is facilitated by institutional factors, the study showed that acceptability of CAC as a maternal health intervention by individual professionals was also pivotal. The Ethiopian case demonstrated that regardless of policy efforts to increase accessibility, ambiguous legal frameworks invite subjective interpretations which hinder pathways to safe abortions [Citation31,Citation32].

Exposure

With constant exposure to cases of morbimortality attributed to unsafe abortions, individuals’ perceptions shifted towards framing termination as a maternal emergency and consequently altered their attitudes and behaviours as demonstrated in below. This behavioural shift proved essential in bridging the divide between governance and accessibility in restrictive contexts and can facilitate timely provision ().

Figure 3. An illustration of attitudes, behaviours and how they evolve when exposed to workplace factors.

The Tanzania case showed that in the absence of strong institutions, health care professionals took advantage of the divide between governance and access to sell abortion medicines privately and subsequently making profits from women’s needs. On the other hand, they perceived ‘themselves’ as the last resort in saving lives, whether clandestinely or legally. Therefore, selling misoprostol was not perceived as deviant and ‘bad’ behaviour but as a responsibility where the government has failed [Citation27].

Occupational support

The absence of support mechanisms in the workplace while exposed to workplace stigma, verbal, and emotional abuse, can increase the risk of behavioural shift towards objections. This shift is detrimental to the timeliness of provision and can lead to unnecessary delays, transfer or denied service.

Competence

In-service training in Ethiopia was a critical factor in health care professionals’ competences. On the contrary, the Tanzanian case showed that the lack of adequate training and knowledge affects the actions, decisions, and behaviours of professionals regardless of their level willingness to provide services. Consequently, turning away clients or transferring them to someone else with better competences which created unnecessary delays.

Resource scarcity

Cases of illicit sales of misoprostol by health care professionals were a result of the high demand of misoprostol and PAC contraceptives supply inconsistencies. The provision and demand gap of CAC was not the only factor influencing these illicit sales in Tanzania, but the precariat employment situation resulted in the need to supplement incomes and factored in their behaviours towards provision. Therefore, though individuals might act altruistically to help women and girls, they also act in self-interest to benefit from clients’ desperation and needs.

Similarities and differences in relation to other studies

Scholars such as Keogh et al. [Citation3] and Murdoch et al. [Citation6] claim that personal characteristics interfere with the accessibility of CAC. Their findings conform with this study that due to this interference, addressing the accessibility problem at material and policy level alone is insufficient if it does not include interventions addressing subjective restrictive concerns impacting the accessibility of CAC.

According to Roets et al. [Citation33], involving restrictive health care professionals in decision-making exposes them to the realities of the consequences of their behaviours and shifts their perceptions towards positive framing of the abortion problem. The findings of this study agree with this claim that exposure can be a vehicle for behavioural change. However, exposure can also have negative effects on individuals. The exposure to severe CAC cases in the absence of occupational support can lead to trauma and negative behaviours which inhibit provision. Zareba et al. [Citation34] also claimed that constant exposure to abortion scenes and workplace stigma without counselling has adverse psychological effects on health care professionals.

Benson et al. [Citation35] conceptualised retraining as an evidence-based intervention which can build health care professionals’ confidence in their competence to provide safe abortion services and mitigate unnecessary delays. This study agrees with the above claim and adds that retraining improves professionals’ confidence in their knowledge and skills. However, these initiatives should always be accompanied by sustainable resource provision of material, human, and emotional forms to mitigate effects of work overload and burnout on competent individuals. Studies claim that resource shortages affect the quality of services clients receive, cause unnecessary delays and insufficient information for clients to make informed decisions [Citation36].

Strengths and weaknesses

The study’s strengths derive from its interpretive analytical approach and its ability to integrate existing evidence from mostly academic literature and non-academic sources—also, the small number of sources included allowed an in-depth exploration of underlying factors influencing attitudes and behaviours. However, a retrospective analysis of attitudes and behaviours might not account for changes that occurred between the time data was collected and the time of this study which weakened the analysis. Moreso, the use of interpretive textual analysis on literature intended to address specific questions and aims also pose an over-interpretation risk. Though divergent in its methodological approach, the study was guided and stayed close to established methodologies for scoping review [Citation8], comparative case study design [Citation9], interpretive textual analysis [Citation12] and relied on health care definitions of key terminologies [Citation1,Citation13,Citation37]. Finally, the interpretive analysis allowed the study to describe the phenomenon beyond the extent of scoping reviews.

Relevance of the findings

The study provides a new ambitious and innovative approach which forgoes the limitations of orthodox literature reviews. This approach allowed the study to add a new perspective to the CAC discourse by describing and interpreting factors influencing health care professionals’ attitudes and behaviours towards CAC, rather than identifying and listing them as is the tradition in literature reviews.

Conclusion and future research

The study demonstrated that health care professionals’ attitudes and behaviours play a significant role in bridging the CAC unmet need gap. However, these attitudes and behaviours are vulnerable when exposed to social and institutional factors. This exposure might lead to behavioural shift which may widen the CAC unmet need gap, particularly in restrictive settings. Therefore,

Institutions should ensure the sustainability of behaviours and attitudes facilitating access to safe abortions and CAC through continuous evaluation, in-service training, and occupational support.

There is a need for a cross-national collaboration between regional states and actors to find pathways towards convergencies in interventions aimed at increasing access and provision.

Institutions should integrate and couple accessibility interventions with measures to increase acceptability when designing CAC interventions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dalarna University, Department of Health and Welfare for their support in making this study a success. We would also like to thank Rahel Tesfa Maregn and Rossella Tatti who peer-reviewed earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- WHO: Abortion [internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Nov 25. [cited 2022 Jan 29]; Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/abortion#tab=tab_1.

- Ganatra B, Gerdts C, Rossier C, et al. Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010–14: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2372–2381.

- Keogh LA, Gillam L, Bismark M, et al. Conscientious objection to abortion, the law and its implementation in Victoria, Australia: perspectives of abortion service providers. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20(1):11.

- Bain EL, Amoakoh-Coleman M, Tiendrebeogo KS, et al. Attitudes towards abortion and decision-making capacity of pregnant adolescents: perspectives of medicine, midwifery and law students in Accra, Ghana. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2020;25(2):151–158.

- MacFarlane KA, O’Neil ML, Tekdemir D, et al. Politics, policies, pronatalism, and practice: availability and accessibility of abortion and reproductive health services in Turkey. Reprod Health Matters. 2016;24(48):62–70.

- Murdoch J, Thompson K, Belton S. Rapid uptake of early medical abortions in the Northern Territory: a family planning-based model. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;60(6):970–975.

- Juarez F, Bankole A, Palma JL. Women’s abortion seeking behavior under restrictive abortion laws in Mexico. PLOS One. 2019; 14(12):e0226522.

- Peters MD, Marnie C, Tricco AC, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020; 18(10):2119–2126.

- Goodrick D. Comparative case studies: methodological briefs. Impact Evaluation. 2014; 9 [Online]. Available from: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/754-comparative-case-studies-methodological-briefs-impact-evaluation-no-9.html.

- McArthur A, Klugárová J, Yan H, et al. Innovations in the systematic review of text and opinion. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):188–195.

- Jaipal-Jamani K. Discourse analysis: a transdisciplinary approach to interpreting text data. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2014.

- Allen M. The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2017.

- WHO. Expanding health worker roles for safe abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. (WHO/RHR:16.02)

- Guttmacher Institute: Induced abortion and postabortion care in Tanzania [Internet]. New York (NY): The Guttmacher Institute; 2016 March [cited 2021 Mar 10]; Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/induced-abortion-and-postabortion-care-tanzania.

- Guttmacher Institute: Induced Abortion and Postabortion Care in Ethiopia [Internet]. New York (NY): 2017. Jan [cited 2021 May 10]; Available: https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/induced-abortion-ethiopia#.

- Carolan CM, Forbat L, Smith A. Developing the DESCARTE model: the design of case study research in health care. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(5):626–639.

- Methley AS, Campbell A, Chew-Graham C, et al. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):579–510.

- JBI: JBI template source of evidence details, characteristics and results extraction instrument [Internet]. Adelaide: 2020. Mar 24 [cited 2022 Jan 17]; Available from: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/3283910953/11.3.7.3+Data+extraction.

- NVivo [Software]. Version 12. London: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2018. Available from: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home.

- Michel-Schuldt M, McFadden A, Renfrew A, et al. The provision of midwife-led care in low-and Middle-income countries: an integrative review. Midwifery. 2020;84:102659.

- Mendeley Reference Manager [Software]. Version 2.64.0. Amsterdam: Mendeley Ltd; 2021. Available from: https://www.mendeley.com/search/.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473.

- Ewnetu DB, Thorsen VC, Solbakk JH, et al. Still a moral dilemma: how Ethiopian professionals providing abortion come to terms with conflicting norms and demands. BMC Med Ethics. 2020;21(1):1–7.

- Taddele T, Theodros G, Taye G, et al. Factors associated with health care provider knowledge on abortion care in Ethiopia: a further analysis on emergency obstetric and newborn care assessment 2016 data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1014.

- McLean E, Desalegn DN, Blystad A, et al. When the law makes doors slightly open: ethical dilemmas among abortion service providers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20(1):60.

- Blystad A, Haukanes H, Tadele G, et al. The access paradox: abortion law, policy and practice in Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zambia. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):1–15.

- Solheim IH, Moland KM, Kahabuka C, et al. Beyond the law: misoprostol and medical abortion in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. Soc. sci. med. 2020;245:112676.

- Yegon E, Ominde J, Baynes C, et al. The quality of postabortion care in tanzania: service provider perspectives and results from a service readiness assessment. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2019;7(2):315–326.

- Baynes C, Yegon E, Lusiola G, et al. Women’s satisfaction with and perceptions of the quality of postabortion care at public-sector facilities in mainland Tanzania and in Zanzibar. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2019;7(2):299–314.

- Sambaiga R, Haukanes H, Moland KM, et al. Health, life and rights: a discourse analysis of a hybrid abortion regime in Tanzania. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):1–12.

- Bo M, Zotti C, Charrier L. Conscientious objection and waiting time for voluntary abortion in Italy. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2015;20(4):272–282.

- Caruso E. Abortion in Italy: forty years on. Fem Leg Stud. 2020;28(1):87–96.

- Roets E, Dierickx S, Deliens L, et al. Healthcare professionals’ attitudes towards termination of pregnancy at viable stage. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(1):74–83.

- Zaręba K, Banasiewicz J, Rozenek H, et al. Emotional complications in midwives participating in pregnancy termination procedures—Polish experience. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2776.

- Benson J, Healy J, Dijkerman S, et al. Improving health worker performance of abortion services: an assessment of post-training support to providers in India, Nepal and Nigeria. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):1–15.

- Lattof SR, Coast E, van der Meulen Rodgers Y, et al. The mesoeconomics of abortion: a scoping review and analysis of the economic effects of abortion on health systems. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0237227.

- WHO, Guttmacher Institute: Worldwide, an estimated 25 million unsafe abortions occur each year [Internet]. New York: 2017. Sep [cited 2021 Feb 28]; Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/news-release/2017/worldwide-estimated-25-million-unsafe-abortions-occur-each-year#.