Abstract

Purpose

While most preconception care (PCC) interventions are aimed at women, men are also in need of PCC to reduce risk factors affecting the spermatozoa quality. The objective of this study is to explore male perceptions regarding the need to engage in PCC.

Materials and methods

In a mixed-method cross-sectional study, 229 men participated with a questionnaire and 14 individual semi-structured interviews were conducted. Questionnaires data were analysed using multiple regression analyses. The interviews were analysed using thematic analyses.

Results

Most men did not retrieve preconceptional information (n = 135; 59.0%) nor visited a preconceptional consult (n = 182; 79.5%). Men who categorised their preconceptional lifestyle as unhealthy (score ≤6 out of 10) less often retrieved information (adjusted OR 0.36 [95% CI 0.14–0.93]) than men with a healthy preconceptional lifestyle. While several men expressed their fear for infertility, this did not lead to an increased uptake of PCC as men felt they were healthy enough already.

Conclusion

Despite high awareness of the positive influence of a healthy lifestyle, the perceived need for preparing for pregnancy among men remains low. Tailoring preconceptional information towards male needs provides a window of opportunity to improve men’s reproductive health and possibly the health of future generations.

摘要

目的:虽然大多数孕前保健(PCC)干预措施都是针对女性的, 但男性也需要PCC来减少影响精子质量的风险因素。这项研究的目的是探讨男性对参与PCC的必要性的看法。

材料和方法:在一项混合方法的横断面研究中, 229名男性参与了问卷调查, 并进行了14次个体半结构化访谈。对问卷数据进行多元回归分析。访谈采用专题分析方法进行分析。

结果:大多数男性没有获取孕前信息(n=135; 59.0%), 也没有孕前咨询(n=182;79.5%)。将他们的孕前生活方式归类为不健康(≤6分, 满分10分)的男性比有健康孕前生活方式的男性更少获取信息(调整后的OR 0.36 [95%CI 0.14-0.93])。虽然一些男性表达了他们对不育的恐惧, 但这并没有导致获取PCC的增加, 因为男性觉得自己已经足够健康了。

结论:尽管人们对健康生活方式的积极影响有很高的认识, 但男性对孕前准备的感知需求仍然很低。针对男性需求调整孕前信息, 为改善男性生殖健康提供了机会之窗, 并可能改善子孙后代的健康。

Introduction

The health behaviours of men have a significant effect on semen quality and can, therefore, influence both pregnancy- and neonatal outcomes [Citation1,Citation2]. Recent studies suggest that the overall semen quality has been decreasing over the past decades and that awareness of potential factors influencing men’s fertility remains poor [Citation3,Citation4]. A large body of evidence established several factors that affect the quality and genetic integrity of spermatozoa, such as obesity, advancing paternal age, medication use and several lifestyle factors including smoking, alcohol use, recreational drug use and poor diet [Citation2,Citation5–14]. Addressing these issues through preconception care (PCC) is proven to be a good opportunity to promote not only reproductive health but also to discuss overall health issues [Citation15]. PCC is defined by the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention as ‘interventions that aim to identify and modify biomedical, behavioural, and social risks to a woman’s health or pregnancy outcome through prevention and management’ [Citation16]. While the majority of health promotion through PCC is aimed at women, research shows that 60% of men are also in need of PCC due to risk factors affecting the quality of spermatozoa [Citation17]. A previous review elaborated on important aspects of PCC for men: e.g. past medical and surgical history, medication use and family history [Citation10].

The prevalence of men ever discussing PCC-related health information with a health care provider varies between 8% and 11%, while 52% of men do not recall ever hearing a preconception health message [Citation18,Citation19]. Moreover, the majority of men admit to making no preconceptional lifestyle adjustments to improve their health and fertility [Citation20,Citation21]. However, encouraging men to actively prepare for pregnancy does have potential health benefits as male ‘pregnancy planners’ are more likely than other men to reduce smoking, reduce alcohol consumption and eat more healthily in preparation for pregnancy [Citation21]. Since the prevalence of paternal risk factors remains high, the association between paternal and maternal health behaviours is strong, and there are no specific PCC-guidelines for men, it is suggested that PCC should be focussed more on the couple, rather than only on women [Citation22,Citation23]. Despite some small studies, still little is known about the motives, perceptions and needs of men regarding PCC. Therefore, this study aimed to explore male perceptions regarding the need to engage in PCC.

Methods

Study design

This study was a secondary analysis of the APROPOS-II study, conducted in six municipalities in the Netherlands between 2019 and 2021 [Citation24]. In this stepped-wedged randomised controlled trial, a locally tailored PCC-intervention is implemented and evaluated among prospective parents, a detailed description of the design and data collection of the APROPOS-II study has been published elsewhere [Citation24]. In the Netherlands, PCC is generally provided within primary care where general practitioners (GPs) and midwives are the commonly appointed healthcare providers to facilitate PCC-consultations which are usually reimbursed by the mandatory health insurance [Citation25]. To explore male perceptions regarding PCC, a mixed-method approach was used including a questionnaire and semi-structured interviews. The questionnaires were used to provide insight into preconceptional lifestyle behaviours of the participants, whereas the interviews gathered a more in-depth understanding of the participants’ preparation for pregnancy, and attitudes regarding PCC. This study was approved by the Medical Ethical Review Board (MEC2019-0278) of the University Medical Centre Rotterdam (Erasmus MC). Following the Declaration of Helsinki, all respondents provided signed informed consent.

Quantitative data collection

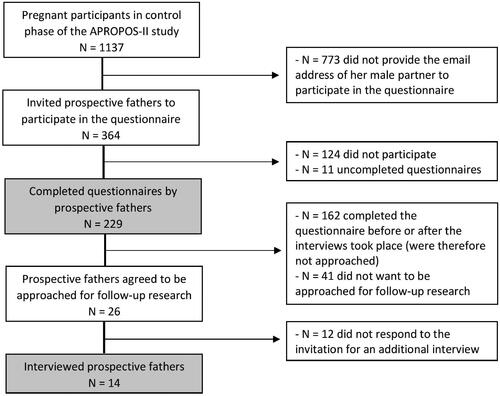

The male participants of this study were recruited through their female pregnant partners, who also participated in the APROPOS-II study and were recruited by their primary care midwife. A flowchart of the recruitment of participants is displayed in . Men were asked to fill out a single questionnaire including 31 questions. The questionnaire was designed based on previous literature and contained four sections: their wish to conceive, pregnancy preparation, healthy lifestyle behaviours and personal demographics [Citation21,Citation26,Citation27]. The questionnaire took about 10–15 minutes to complete and was developed in Dutch, after which it was additionally translated into English, Turkish and Polish. Together, these languages are mastered by the majority of the inhabitants of the participating municipalities. The English version of the questionnaire is available in the supplemental material.

Qualitative data collection

In the questionnaire, male participants were asked to indicate their willingness to participate in an additional individual semi-structured interview (). This method provided an opportunity to collect open-ended data, explore participant thoughts, feelings and beliefs about PCC and delve into personal issues [Citation28]. The semi-structured interview particularly focussed on the needs of men in the preconceptional period and also contained four sections: pregnancy intentions, pregnancy preparation, health & lifestyle and involvement. The interview guide was based on concepts derived from literature [Citation26,Citation29,Citation30]. The English version of our interview guide is provided as supplemental material. The semi-structured interviews were conducted in June and July of 2020 by two experienced researchers (VYFM & ALS) and lasted about 30–45 minutes. After providing informed consent, men were invited to an online video meeting during which the interview was recorded. Before the start of the interview, verbal consent was requested to audio record the interview. All participants received a voucher for €25,- as compensation for their time and contribution.

Outcomes measures

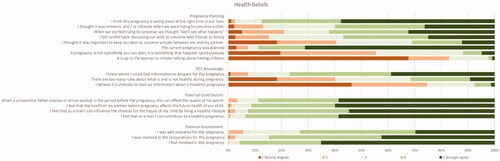

The following socio-demographic characteristics were assessed: age, ethnicity, educational level and being a first-time father. Ethnicity was categorised as either Dutch or Non-Dutch. Educational level was classified as either high (university or higher vocational education) or medium/low (secondary education or lower). Actively preparing for pregnancy was defined as either retrieving PCC-information (e.g., Internet, books, family, etc.) or visiting a health care provider for a PCC-consult. Motives behind preparation for pregnancy were assessed through several multiple-choice questions with open-ended answer options for personal motives. The following lifestyle behaviours were assessed in the questionnaire for both the prenatal and preconception period: smoking and alcohol use. Preconceptional smoking and alcohol use were categorised as either: no use, quit before or during the pregnancy and continuation of the behaviour. A self-perceived overall preconceptional lifestyle grade was assessed on a scale from 1 to 10 and categorised by the research team as unhealthy (≤6), healthy (7 or 8) or very healthy (9 or 10). Finally, the questionnaire contained 18 statements categorised into pregnancy planning, PCC-knowledge, paternal contribution to a healthy pregnancy and paternal involvement in the pregnancy. The opinions on these statements were graded on a 5-Point Likert Scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Data analysis

The primary outcome of this study was the male perception regarding the need to engage in PCC (qualitative- & quantitative data). Secondary outcomes were; preconceptional (lifestyle) behaviours and motives behind pregnancy preparation (quantitative data). Data from the questionnaire were coded and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Baseline characteristics of all participants are presented as means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables or as numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Logistic regression analysis was performed to calculate crude odds ratios (OR) and accompanying 95% confidence intervals (CI) by univariate analysis. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) were calculated using multiple logistic regression, adjusted for the following potential confounders: age, ethnicity, educational level and being a first-time father.

For the qualitative data analysis, interviews were first transcribed verbatim and analysed using Atlas.Ti (version 8) software [Citation31]. Thematic analysis was conducted to identify key issues and themes [Citation32]. First, an initial coding scheme was generated. This coding scheme was derived from occurring topics and concepts that were included in the interview guide; the initial coding was conducted by one researcher (VYFM). To ensure the reliability of the study, extraction and coding were verified by a second researcher (MPHK). Discrepancies were discussed until consensus was attained and both researchers agreed on the final coding scheme. Translated illustrative quotes were selected to reflect the thematic interpretation. After 14 interviews, data saturation occurred when no new concepts were introduced.

Results

Findings from the questionnaire

Of the 364 men approached to participate in our study, 229 men completed the questionnaire resulting in a response rate of 63%. Only 94 (41.0%) men retrieved PCC-information before conception took place; primarily from the Internet (75.5%) or via their partner (53.2%). There were 47 (20.5%) men who consulted a health care provider for a PCC-consult (). The main reason for not opting for a PCC-consult was the lack of need for a conversation with a health care provider (n = 55; 65.5%) and having the perception of already knowing enough about a healthy pregnancy (n = 53; 63.1%).

Table 1. Men’s preparation for pregnancy.

Men who graded their preconception lifestyle as unhealthy were significantly less likely to retrieve PCC-information than men who graded their lifestyle as healthy (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 0.36 (95%CI 0.14–0.93) (). Men who graded their preconception lifestyle as very healthy were significantly more likely to have attended a PCC-consult than men who graded their preconception lifestyle as healthy (aOR 4.56 (95%CI 1.90–10.97)). Most men felt comfortable discussing their wish to conceive with their friends or family (57%) and that the pregnancy was planned (89%), and the majority of men strongly disagreed with the statement that it is up to the woman to initiate talking about having children (67%) (). Most men knew where to find PCC-information (78%) and did not feel it was stressful to look up PCC-information (75%).

Table 2. Associations between preconceptional lifestyle factors and actively preparing for pregnancy.

Findings from the interviews

The majority of interviewed men were highly educated (tertiary education or higher level), their age varied between 28 and 36 years, and eight out of 14 respondents were about to be a father for the first time ().

Table 3. Demographic characteristics of the interviewed men.

We identified four major themes of perceptions around PCC:

Wish to conceive

The majority of the men were first-time fathers. Among these men, an underlying fear of infertility existed. Not knowing if they were able to conceive a child made them feel anxious and affected their masculinity. One respondent even mentioned that becoming a father is part of a men’s identity and it, therefore, affected how he feared infertility. Many men felt distressed when their partners did not become pregnant after only one or two months of trying. However, this fear for infertility did not result in an increased uptake of PCC.

Respondent 3: ‘After 2 times [not being pregnant], I noticed that I was a bit disappointed, I thought “How is this possible? What is the reason for this?”. So I already felt the pressure. But luckily it happened the 3rd or 4th time. But that was a big deal for me.’

Preparation for pregnancy

Some men searched for information online, other suggested options to attain PCC-information such as reading a book or listening to a podcast. Several men expressed the feeling of not wanting to know too much or the fact that there was only limited availability of PCC-information for men.

Respondent 2: ‘I have tried many times to look up things that are somewhat relevant for men, but there weren’t that many.’

The majority of men expressed that their partner was one of the main sources of essential PCC information. Many men relied on the preparation of their partners before pregnancy.

Respondent 5: ‘I am quite practical, in the sense of only looking up information when I need it. I have a partner who can prepare herself very well, so she prepared herself very well and therefore I was also prepared’

Lifestyle behaviours

After asking the respondents if they changed anything in their lifestyle to actively prepare for pregnancy, almost all men expressed that they felt already healthy enough, therefore no lifestyle behaviour change was needed. Due to the social context of alcohol, almost all men found it difficult to abstain from alcohol during the preconception period in the company of their friends. Most men opted for reducing their alcohol use in the preconception period instead of abstaining from alcohol entirely. Most men compared themselves to some of their (unhealthier) friends and family to validate the perception of their healthy lifestyle.

Respondent 13: ‘Not drinking alcohol is part of the deal, I also don't smoke so I didn’t have to quit, and I neither do drugs. I didn't have to change much in that regard. I'm also not overweight, as far as I know. So I didn't have to adjust a lot, I thought it all will be fine.’

Some men believed that beneficial pregnancy outcomes were almost solely influenced by the woman and therefore outside their control. This influenced their motivation to live a healthy lifestyle, especially for experienced fathers when a previous healthy pregnancy already took place.

Respondent 7: ‘I think it's [contribution of one’s health to that of the future child] for 80%-90% influenced by the woman. So in the period that you try to conceive, you also try to live a little healthier. But after that, I think it mostly depends on the woman.’

Involvement of men in PCC

Several men struggled with the fact that the available PCC-information was mainly communicated in a feminine tone of voice. The narrative was commonly suggested as pregnancy being a ‘female thing’ and that information was limited to the kind of things you can do as a man to make your life easier for yourself with a pregnant partner. For example, a commonly mentioned book most respondents read and referred to is called ‘Help, I impregnated my wife!’. Most men could see the humour in this kind of narrative, but were not always able to identify with this sort of stereotyping of the male role in pregnancy.

Respondent 2: ‘It [pregnancy information] is presented in a way which I dislike, compared to all the other information you receive. As a man you are always pushed into the corner, for instance; “you keep hoping that the birth does not start when Ajax plays against Feyenoord [another Dutch soccer club] because then you will miss the match”. Very stereotyping’

PCC-information provided by a health care provider was highly appreciated and viewed as a credible information source by the majority of interviewed men. One man even suggested a one-on-one consultation with the midwife so all his questions and concerns could be addressed. While some men valued the involvement of their GP concerning preconceptional risk factors, others felt it is not the GP’s responsibility to mention PCC-information if not asked for.

Respondent 2: ‘It [a GP proving PCC-information] is meant well, but I would think “I believe the doctor has better things to do than spending time on me to give me more information.”’

The majority of interviewed men expressed their desire to receive factual PCC-information on, for instance, ways to improve their sperm quality or information on how to reduce time to conception. The following channels to distribute this preferred PCC-information were suggested: posters, podcasts, books, an app, social media, radio ads, schools or information adjoined with an ovulation test. Most men expressed that the PCC-message should include some kind of humour, sarcasm or cynicism to make the information stand out more and make it more memorable.

Respondent 10: ‘But besides that [providing informative PCC-information], also just stories specifically written for men. In these current magazines [.] it's often stories told by women. Yet, the male role is quite underexposed, I believe. Maybe an app especially for fathers-to-be could be an idea, although I'm not one going to attend a forum or chat with fathers about how I experienced everything’.

Discussion

Findings and interpretation

The results of this study show that most men are aware of the positive influence of a healthy lifestyle on their reproductive health and know where to find PCC-information. Nonetheless, they perceived the need for actively preparing for pregnancy as low. The majority of men did not retrieve any PCC-information before conception nor visited a health care provider for a PCC-consult. The barriers for retrieving PCC-information are higher for men who grade their preconceptional lifestyle as unhealthy. The conducted interviews also confirmed a low perceived need for PCC. Men expressed their insecurity on how the possibility of infertility affects their masculinity, the majority expressed that they felt they were healthy enough and did not need PCC. Finally, men proposed different channels to reach prospective fathers with PCC-information.

Strengths and weaknesses

The main strength of this study is the use of a mixed-method study design, combining the quantitative insights of a large dataset of men with the in-depth results of the semi-structured interviews.

A potential limitation of our study is the possibility to provide socially desirable answers to the provided questions and the self-reported answers in the questionnaire negatively affecting validity [Citation33]. However, the questionnaire contained mainly multiple-choice or dichotomous questions (yes or no) combined with statements using a Likert scale (completely disagree – completely agree), diminishing the risk for over-or underreporting [Citation34]. While most people are prone to overestimating their health status, the self-perceived overall lifestyle grade should be interpreted with caution. The overall lifestyle grade is a non-validated measure and does not necessarily reflect the actual quality of health. In addition, recruiting men for the interviews using a convenience sampling technique could have potentially resulted in a sample of well-prepared men keen to share their experiences, thereby possibly leading to selection bias. The majority of interviewed men were highly educated and presumably less inclined to have risky health behaviours. However, the majority of participants undertook no action to actively prepare for pregnancy nor changed their unhealthy preconceptional lifestyle behaviours.

Similarities and differences in relation to other studies

The percentage of men retrieving PCC-information in our study was comparable to a previous study in which almost half of the men looked up PCC-information [Citation21]. This study also showed that, while the majority of men rated their health status to be good or excellent (84.1%), still 49.7% of men were overweight [Citation21]. This lack of perceived need for PCC likewise resembles the interviewed men in our study as only 1 in 4 men ceased alcohol consumption preconceptionally or in the first trimester. Although the evidence concerning the effect of (habitual) alcohol consumption on semen quality remains contradictory, previous studies similarly found that many prospective fathers reduce their alcohol consumption before conception due to solidarity and a sense of responsibility for their pregnant partner [Citation27,Citation35–37].

The results of our study showed that once the couples started trying to conceive, some (unexpected) feelings surfaced, such as impatience and fear of infertility. A previous analysis of an online discussion board for male infertility showed that men may experience feelings of uncertainty, inadequacy, failure, anger, frustration and worry about their partner’s feelings [Citation38]. Several men in our study elaborated on the fact that potentially being infertile affects their masculinity and this, therefore, keeps them from seeking help. However, this fear for infertility did not result in preconceptional lifestyle behaviour change, an increase in retrieving PCC-information nor a PCC-consultation. Previous fertility research among prospective fathers confirmed our findings and elaborated on how virility is intertwined with the cultural concept of masculinity [Citation39–41]. Respondents of one of these qualitative studies described that fertility problems can make men feel ‘less of a man’ [Citation39]. This is not a new concept or solely related to fertility issues, earlier research found that young men almost exclusively explained that it was not ‘macho’ to ask for help or advice and reported feelings of vulnerability when seeking help due to a perceived loss of control [Citation42]. Another barrier for not asking for help is the desire of prospective parents to keep their wish to conceive a secret, for example out of fear that they may not become pregnant and that it might be painful and annoying if others inquire about this [Citation43,Citation44].

Open questions and future research

Reducing the stigma on talking about a wish to conceive and actively preparing for pregnancy only being a ‘female thing’, could potentially improve the need for PCC. However, a previous study found that most prospective parents are not receptive to PCC-information when not actively planning a pregnancy [Citation19]. Instead of attending health clinics or visiting their GP, young men are more likely to seek health information online [Citation42]. Another suggested approach to reach men with PCC-messages might be ‘branding’ a social marketing tool known to develop an identity for PCC [Citation19]. Future research on PCC-interventions should gain insight into strategies to reach men with PCC-information and to discover what motivates and triggers them to improve their preconceptional lifestyle behaviours. To engage men in PCC the notable discrepancy between the intention (wanting the best reproductive health) and behaviour (actually improving lifestyle behaviours) among men should be further investigated.

Conclusion

While most men are aware of the positive influence of a healthy lifestyle and know where to find PCC-information, their perceived need for actively preparing for pregnancy remains low. Future studies could elaborate more on the expressed fear for infertility, along with the consequences this has on PCC-behaviours. Men in this study proposed different channels to reach prospective fathers with PCC-information, i.e., social media, radio ads and podcasts. The insights from our study provide a window of opportunity to tailor PCC-information to men and possibly improve the health of future generations.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all prospective fathers who participated in this study and the participating midwifery practices for their contribution to the data collection.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Moss JL, Harris KM. Impact of maternal and paternal preconception health on birth outcomes using prospective couples' data in add health. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291(2):287–298.

- Fleming TP, Watkins AJ, Velazquez MA, et al. Origins of lifetime health around the time of conception: causes and consequences. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1842–1852.

- Merzenich H, Zeeb H, Blettner M. Decreasing sperm quality: a global problem? BMC Public Health. 2010; 10(1):2424.

- Daumler D, Chan P, Lo KC, et al. Men's knowledge of their own fertility: a population-based survey examining the awareness of factors that are associated with male infertility. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(12):2781–2790.

- Sallmén M, Sandler DP, Hoppin JA, et al. Reduced fertility among overweight and obese men. Epidemiology. 2006;17(5):520–523.

- Singh AK, Tomarz S, Chaudhari AR, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus affects male fertility potential. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;58(4):403–406.

- Eisenberg ML, Chen Z, Ye A, et al. Relationship between physical occupational exposures and health on semen quality: data from the longitudinal investigation of fertility and the environment (LIFE) Study. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(5):1271–1277.

- Sharma R, Agarwal A, Rohra VK, et al. Effects of increased paternal age on sperm quality, reproductive outcome and associated epigenetic risks to offspring. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015; 13(1):35.

- Kovac JR, Addai J, Smith RP, et al. The effects of advanced paternal age on fertility. Asian J Androl. 2013;15(6):723–728.

- Frey KA, Navarro SM, Kotelchuck M, et al. The clinical content of preconception care: preconception care for men. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(6 Suppl 2):S389–S95.

- Hampton T. Researchers discover a range of factors undermine sperm quality, male fertility. JAMA. 2005;294(22):2829–2831.

- Auger J, Eustache F, Andersen AG, et al. Sperm morphological defects related to environment, lifestyle and medical history of 1001 male partners of pregnant women from four european cities. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(12):2710–2717.

- Fullston T, McPherson NO, Zander-Fox D, et al. The most common vices of men can damage fertility and the health of the next generation. J Endocrinol. 2017;234(2):F1–f6.

- Oldereid NB, Wennerholm UB, Pinborg A, et al. The effect of paternal factors on perinatal and paediatric outcomes: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2018;24(3):320–389.

- Warner JN, Frey KA. The well-man visit: addressing a man's health to optimize pregnancy outcomes. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(2):196–202.

- Johnson K, Posner SF, Biermann J, et al. Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care—United States: report of the CDC/ATSDR preconception care work group and the select panel on preconception care. Morbid Mortal Weekly Report. 2006;55(RR-6):1–23.

- Choiriyyah I, Sonenstein FL, Astone NM, et al. Men aged 15-44 in need of preconception care. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(11):2358–2365.

- Frey KA, Engle R, Noble B. Preconception healthcare: what do men know and believe? Journal of Men's Health. 2012;9(1):25–35.

- Mitchell E, Levis D, Prue C. Preconception health: awareness, planning, and communication among a sample of US men and women. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(1):31–39.

- Bodin M, Tyden T, Kall L, et al. Can reproductive life plan-based counselling increase men's fertility awareness? Ups J Med Sci. 2018;123(4):255–263.

- Shawe J, Patel D, Joy M, et al. Preparation for fatherhood: a survey of men's preconception health knowledge and behaviour in England. PloS One. 2019;14(3):e0213897.

- Agricola E, Gesualdo F, Carloni E, et al. Investigating paternal preconception risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes in a population of internet users. Reprod Health. 2016;13:37.

- Shawe J, Delbaere I, Ekstrand M, et al. Preconception care policy, guidelines, recommendations and services across six european countries: Belgium (flanders), Denmark, Italy, The Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom [doi: 10.3109/13625187.2014.990088]. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. 2015; 20(2):77–87.

- Maas VYF, Koster MPH, Ista E, et al. Study design of a stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect of a locally tailored approach for preconception care - the APROPOS-II study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):235.

- de Jong-Potjer LBM, Bogchelman M, Jaspar AHJ, et al. The Preconception care guideline by the Dutch Federation of GP’s. 2011. Available from: https://guidelines.nhg.org/product/pre-conception-care. Accessed 23 July 2021.

- Poels M, Koster MPH, Franx A, et al. Parental perspectives on the awareness and delivery of preconception care. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):324.

- Bodin M, Käll L, Tydén T, et al. Exploring men's pregnancy-planning behaviour and fertility knowledge:a survey among fathers in Sweden. Ups J Med Sci. 2017;122(2):127–135.

- DeJonckheere M, Vaughn LM. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour. Fam Med Community Health. 2019;7(2):e000057

- Goossens J, Van Hecke A, Beeckman D, et al. The intention to make preconception lifestyle changes in men: associated socio-demographic and psychosocial factors. Midwifery. 2019;73:8–16.

- van der Zee B, de Wert G, Steegers EA, et al. Ethical aspects of paternal preconception lifestyle modification. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(1):11–16.

- Soratto J, Pires DEP, Friese S. Thematic content analysis using ATLAS.ti software: potentialities for researchs in health. Rev Bras Enferm. 2020;73(3):e20190250.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. 2012.

- Gollenberg AL, Mumford SL, Cooney MA, et al. Validity of retrospectively reported behaviors during the periconception window. J Reprod Med. 2011;56(3-4):130–137.

- Larson RB. Controlling social desirability bias. International Journal of Market Research. 2019;61(5):534–547.

- Jensen TK, Gottschau M, Madsen JO, et al. Habitual alcohol consumption associated with reduced semen quality and changes in reproductive hormones; a cross-sectional study among 1221 young danish men. BMJ Open. 2014 Oct 2;4(9):e005462.

- Povey AC, Clyma JA, McNamee R, Participating Centres of Chaps-uk, et al. Modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for poor semen quality: a case-referent study. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(9):2799–2806.

- Högberg H, Skagerström J, Spak F, et al. Alcohol consumption among partners of pregnant women in Sweden: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:694.

- Beeder L, Samplaski MK. Analysis of online discussion boards for male infertility. Andrologia. 2019;51(11):e13422.

- Harlow AF, Zheng A, Nordberg J, et al. A qualitative study of factors influencing male participation in fertility research. Reprod Health. 2020; 2020/11/2317(1):186.

- Dudgeon MR, Inhorn MC. Gender, masculinity, and reproduction: anthropological perspectives. International Journal of Mens Health. 2003;2(1):31–56.

- Sylvest R, Fürbringer JK, Pinborg A, et al. Low semen quality and experiences of masculinity and family building. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97(6):727–733.

- Tyler RE, Williams S. Masculinity in young men's health: exploring health, help-seeking and health service use in an online environment. J Health Psychol. 2014;19(4):457–470.

- van der Zee B, de Beaufort ID, Steegers EAP, et al. Perceptions of preconception counselling among women planning a pregnancy: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2013;30(3):341–346.

- Tuomainen H, Cross-Bardell L, Bhoday M, et al. Opportunities and challenges for enhancing preconception health in primary care: qualitative study with women from ethnically diverse communities. BMJ Open. 2013;3(7):e002977.